Abstract

Objective

The effects of binge‐drinking during pregnancy on the fetus and child have been an increasing concern for clinicians and policy‐makers. This study reviews the available evidence from human observational studies.

Design

Systematic review of observational studies.

Population

Pregnant women or women who are trying to become pregnant.

Methods

A computerised search strategy was run in Medline, Embase, Cinahl and PsychInfo for the years 1970–2005. Titles and abstracts were read by two researchers for eligibility. Eligible papers were then obtained and read in full by two researchers to decide on inclusion. The papers were assessed for quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scales and data were extracted.

Main outcome measures

Adverse outcomes considered in this study included miscarriage; stillbirth; intrauterine growth restriction; prematurity; birth‐weight; small for gestational age at birth; and birth defects, including fetal alcohol syndrome and neurodevelopmental effects.

Results

The search resulted in 3630 titles and abstracts, which were narrowed down to 14 relevant papers. There were no consistently significant effects of alcohol on any of the outcomes considered. There was a possible effect on neurodevelopment. Many of the reported studies had methodological weaknesses despite being assessed as having reasonable quality.

Conclusions

This systematic review found no convincing evidence of adverse effects of prenatal binge‐drinking, except possibly on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Keywords: fetus, pregnancy, binge‐drinking

The effects of prenatal alcohol consumption on the developing embryo, fetus and child are well known.1 It is generally accepted that heavy drinking is associated with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and fetal alcohol effects such as growth retardation, birth defects and neurodevelopmental problems.2

Animal models have suggested that it is the peak blood alcohol concentration rather than the average intake that determines the level of damage.3 High blood alcohol concentrations are achieved by intake of large volumes of alcohol on a single occasion—that is, binge‐drinking.3

Government advice to pregnant women or to women who may become pregnant differs between countries; some, such as Australia and New Zealand, recommend moderation, whereas others, such as the USA, recommend abstinence. The current UK Department of Health guidelines4 recommend that women who are trying to become pregnant or are at any stage of pregnancy, should not drink more than 1 or 2 units of alcohol once or twice a week, and should avoid episodes of intoxication. However, women's drinking in the general population has increased over the past two decades. For example, the proportion of women in the 16–44‐year, fertile age group drinking more than 14 units per week increased from 17% in 1992 to 33% in 2002. The proportion of women in the 16–24‐year age group who binge‐drink has also increased from 24% in 1998 to 28% in 2002.5

Binge‐drinking is an important topic for women's health, as well as for the fetus and child. For example, binge‐drinking is commonly associated with unprotected sex and unplanned pregnancy.6 Binge‐drinking may then continue to occur up to the time that the pregnancy is recognised. This has been shown in Denmark, even among moderate, social drinkers.7 Therefore, given the increasing proportion of women who binge‐drink, and the potential for adverse effects, this topic is important for both clinicians and policy‐makers who may have an opportunity to intervene with preventive measures.

But is binge‐drinking harmful during pregnancy in women who otherwise drink low‐to‐moderate amounts? It has been suggested that binge‐drinking may do greater harm to the developing fetus than drinking a comparable amount spread over several days or weeks because peak blood concentration is the critical factor.7,8 But what is the evidence for this?

This review was conducted as part of a more general review of the fetal effects of prenatal alcohol consumption.9 In this paper, we report the results of a systematic review of the effects of binge‐drinking on the embryo, fetus and developing child.

Methods

Studies were included if they related to pregnant women, stillborn or live children; if they were case–control, cohort or cross‐sectional studies published between January 1970–July 2005 in the English language in a peer‐reviewed journal; if they included data on miscarriage, stillbirth, impaired growth, preterm birth, (low) birth‐weight, birth defects including fetal alcohol syndrome or neurodevelopmental outcomes; and if there was a measure of binge‐drinking that was reported separately from ‘heavy' drinking. Studies were excluded if there was no quantitative measure of alcohol consumption that could be converted to UK standard units and grams of alcohol; if there was insufficient data for an (adjusted and/or crude) effect measure of binge‐drinking to be extracted; if it was a duplicate publication; or if the study was only available in abstract form.

A computerised literature search was undertaken using the WebSpirs 5 software on Medline (1970–2005), Embase (1980–2005), Cinahl (1982–2005) and PsychInfo (1972–2005). MeSH headings and free text terms were used for the exposure and outcomes. The results were ‘filtered' using the ‘high sensitivity' filter for aetiological studies.10 A copy of the search strategy is shown in the appendix. The electronic search was supplemented by reviewing bibliographies of review articles and discussions with experts in the field.

Titles and abstracts (if present) of all studies identified were reviewed independently by two members of the research team to identify potentially relevant papers; differences were resolved by discussion and no conflicts arose. Papers deemed relevant or of uncertain relevance were obtained and read in full. These were reviewed against inclusion/exclusion criteria independently by two members of the research team to determine which papers to include. Reasons for exclusion were identified and are available from the authors on request.

The quality of all included studies was assessed by the first author using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), as recommended by the Cochrane Non‐Randomized Studies Methods Working Group.11 A study is judged on three areas: the selection of the study groups; the comparability of the groups; and the ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest for case–control or cohort studies, respectively.

A data‐extraction form was designed, piloted and revised. Each included article was read and data extracted by a member of the study team; a second member checked table entries for accuracy against the original article.

A meta‐analysis was not undertaken due to the heterogeneity in methods of the different studies. The studies have been summarised in tables and are discussed below.

Results

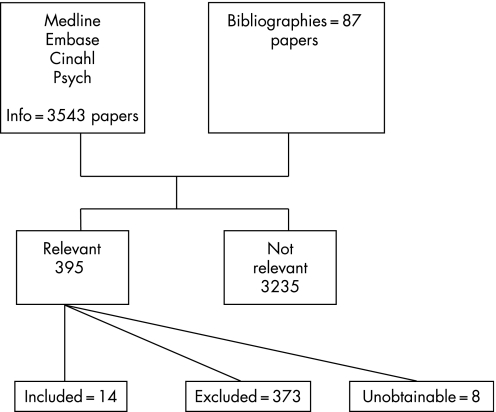

Searches of the databases for the more general review of fetal effects of prenatal alcohol exposure resulted in 3275 papers (see figure 1). Of these, 308 papers were marked as either relevant (121) or of uncertain relevance (187) on the basis of title and abstract (where available). The full text of these papers was obtained. In addition, 87 papers from bibliographies and contact with experts were obtained (395 in total). Of these, 14 papers related to binge‐drinking and were included in this review.

Figure 1 Results of search.

There were 11 separate studies (counting all the papers from the Seattle study12,13,14,15 as one) meeting the inclusion criteria for this review. Four were from the USA, two each from the UK, Australia and Denmark, and one from Canada. Whereas the UK measures alcohol in terms of standard ‘units' (with one unit being equivalent to 8 g of alcohol), other countries tend to refer to standard ‘drinks' (with one drink containing approximately 12 g of alcohol). Binge‐drinking was most commonly defined as consuming five or more drinks on a single occasion (60 g of alcohol, equivalent to 7.5 UK units), but has also been defined as 10 or more UK units (80 g)16 and 40–45 g (equivalent to about 5 UK units).17 One study only considered a woman to be a binge‐drinker if she consumed 5 or more drinks on an occasion at least once in every fortnight of her pregnancy.8 Many of the studies reported multiple outcomes. Studies varied in the extent to which they adjusted for potential confounders (see online‐only table; please see data supplement online at: http://jech.bmj.com/supplemental).

Birth‐weight, gestational age and growth

Seven of the studies considered these outcomes.6,15,17,18,19,20,21 Three of these studies found an association between binge‐drinking and birth‐weight.15,17,18 Bell & Lumley (1989)18 reported small but statistically significant differences in mean birth‐weight between babies of binge‐drinkers, non‐smoking abstainers and smoking abstainers. Lowest mean birth‐weight was in the babies of smoking abstainers. Sampson et al. (1994)15 reported a small correlation between bingeing—both prior to pregnancy recognition and during pregnancy—and birth‐weight (correlation coefficients: –0.15 and –0.11, respectively). However, the statistical significance of this was not stated. Length, head circumference and subsequent weight (up to 14 years after birth) were not associated with bingeing. The other study17 only found a significant association in the group who were bingers and/or heavy drinkers (1–2 drinks per day in early pregnancy/binged at least once in mid‐pregnancy, or drank 3+ drinks per day in early pregnancy without bingeing in mid‐pregnancy). Thus, it is difficult to separate out the effect of binge‐drinking from heavy drinking. The analyses in both studies were unadjusted for possible confounders.

Birth defects, including fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)

There were three studies that considered this outcome.16,18,22 The first of these counted the mean number of abnormalities at birth and found a significant excess in bingers, particularly if they also smoked 10 or more cigarettes per day. However, a binge was defined as 10 or more units on a single occasion, and the analyses were not adjusted for potential confounders other than smoking. The study by Bell & Lumley (1989)18 was limited by low participation and completeness of data. They found a slight excess of birth defects but this was not statistically significant. The paper by Olsen & Tuntiseranee (1995)22 was a study of the craniofacial features of FAS. They found that newborn children of binge‐drinkers had slightly shorter palpebral fissures but no association was reported with other facial features.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes

Four studies considered these outcomes in relation to binge‐drinking.6,8,12,13,14,23 Two of these used the Bayley Scales of Infant Development at 18 months23 and up to 36 months after birth,6 but neither found a statistically significant difference in score in children of women who binged in pregnancy compared with children of women who did not binge. The only difference found by Nulman et al. (2004)6 was a greater degree of ‘disinhibited behaviour', as shown in the significantly higher scores for adaptability and approach. The study by Bailey et al. (2004)8 reported a significant reduction in verbal IQ and increase in delinquent behaviour in children of women who had binged in pregnancy. However, this study only counted women as bingers if they binged throughout pregnancy, not just on a single occasion. The Seattle Longitudinal Prospective Study on Alcohol and Pregnancy12,13,14 followed children up to age 14 years using a variety of outcome measures. They reported significantly more learning problems and poorer performance, as assessed by both parents and teachers, in children of binge‐drinking mothers. This effect appeared to persist up to age 14 years. The proportion lost to follow‐up was not stated but may have been quite substantial (around 30%), which may have affected the results.

Discussion

The principal finding of this systematic review of the fetal effects of prenatal binge‐drinking is that there is no consistent evidence of adverse effects across different studies. However, there was a possible effect on neurodevelopmental outcomes. With this outcome, the effects, which were generally quite small, included an increase in ‘disinhibited behaviour',6 a reduction in verbal IQ, an increase in delinquent behaviour8, and more learning problems and poorer performance.12,13,14 The studies that considered neurodevelopment were not without problems. It seems that at relatively low amounts of alcohol and infrequent occasions of binge‐drinking, there is no consistent evidence of adverse effects. However, greater frequency of bingeing or higher levels of alcohol consumption may increase the risk of adverse fetal effects.

Searches were limited to English language studies in the four bibliographic databases Medline, Embase, PsychInfo and Cinahl. We did not attempt to access the ‘grey' literature nor did we request further data from authors. For a complete review, we scanned 3630 titles, the vast majority of which did not relate to binge‐drinking. Of those that did, 14 papers were included. In a number of excluded papers, it was impossible to separate the effects of binge‐drinking from general heavy drinking.

The systematic review may have been affected by publication bias in which studies with positive results are both more likely to be submitted and more likely to be accepted for publication. However, if the results are affected by publication bias then it would imply that binge‐drinking may be safer than it appears from the published literature. Similarly, women questioned about their drinking habits in pregnancy tend to under‐report.7 Therefore, actual drinking patterns are likely to be higher and any associations with adverse outcome may be with higher levels of drinking than those reported.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scales. This scale has been used in other Cochrane reviews of non‐randomised studies, such as the use of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy.24 Generally, the studies included in this review scored quite highly. However, this was not a true reflection of the quality of many of the studies, which had problems specific to carrying out research in the area of prenatal alcohol exposure, and which were not covered in the general quality assessment scale.

For example, some studies did not specify when in pregnancy the binge‐drinking occurred. This may be of considerable importance as alcohol may cause different adverse effects at different points in time during pregnancy. For example, organogenesis occurs mainly in the first trimester. Moreover, studies may have included both binge‐drinkers who otherwise drink little and binge drinkers who generally drink substantial amounts. Thus, the quantity of alcohol consumed could confound the binge pattern.

The vast majority of women reduce their alcohol consumption dramatically once they know they are pregnant. However, for the 2–3 weeks between conception and pregnancy recognition, binge‐drinking may be common. In one Danish study, 10–25% of women binged during each of these weeks,7 and a total of 50% of pregnant women reported at least one episode of binge‐drinking from the last menstrual period until pregnancy recognition.25 Thus, any overall measure of binge‐drinking that does not specify when in pregnancy it occurred will be dependent on how early the woman recognised her pregnancy.7

Although it has been shown that concurrent information on average alcohol intake during pregnancy is generally lower than retrospective information referring to the same pregnancy,26,27 no knowledge seems to exist on this topic with regards to binge‐drinking. The better‐quality studies used validated questionnaires or interviews administered antenatally to ask about specific time periods both prior to pregnancy recognition and during pregnancy.

The definition of a binge has changed radically over the years. In the past, it meant an extended period (usually several days) of intoxication; now it commonly refers to drinking six UK units or more on a single occasion—that is, only two or three large glasses of wine28—and, in most studies of pregnant women, it has been defined as five or more drinks on a single occasion.7

Neurodevelopment refers to behaviour as well as several cognitive domains, including attention, thinking, learning, memory and executive functions, most of which may be further subdivided into, for example, focused and sustained attention, visual and auditory attention. Hence, in reporting multiple outcomes, there is considerable scope for chance findings. On the other hand, studies using crude measures of behaviour or any cognitive functions not looking into subdomains may fail to find and report the real effects of binge‐drinking.

Five of the eleven included studies were from the USA. The generalisability of these results to the UK and other European countries may be questionable. Differences in drinking patterns (for example, more or less binge‐type drinking), the extent to which women under‐report drinking in pregnancy (due, for example, to cultural differences in acceptability of alcohol drinking), and ascertainment of outcomes (particularly neurodevelopmental outcomes) may all differ between the USA and Europe. Therefore, the findings should be treated with caution.

Future research needs to consider the accuracy and validity of estimates of alcohol consumption, particularly binge‐drinking. Prospective studies concentrating specifically on binge‐drinking in women whose average consumption is low‐to‐moderate would be of benefit, as would studies including information about timing of alcohol intake in general and binge episodes in particular, across the entire pregnancy. This would allow for more detailed analysis of this area using valid and reliable operational definitions of exposure, outcomes and important confounders. Given that there is no universal agreement on how much constitutes a binge episode, and given the threshold may well be lower in pregnant than in non‐pregnant women, it seems sensible to use several different definitions of binge‐drinking (in the same studies) to find potential effects or a threshold for effects. The specific effects on childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes will require long‐term follow‐up studies with predefined hypotheses concerning neuropsychological outcomes in order to reduce the risk of chance findings. Such studies need to take into account differences in public health information campaigns and alcohol policy between countries.

In the absence of a strong research base on which to make any strong clinical recommendations, we would suggest prioritising research into binge‐drinking during pregnancy. However, considering the evidence of adverse effects from animal studies and hence the potential effects in humans despite the current lack of evidence, from a public health point of view we would suggest that it may be worthwhile recommending pregnant women to avoid binge‐drinking during pregnancy. But equally, from a clinical point of view, when pregnant women report isolated episodes of binge‐drinking in the absence of a consistently high daily alcohol intake, as is often the case, it is important to avoid inducing unnecessary anxiety as, at present, the evidence of risk seems minimal.

What is already known

Heavy drinking during pregnancy has been associated with birth defects and subsequent neurodevelopmental problems.

Although binge‐drinking has increased in the female population, it is unclear whether drinking in this pattern is harmful to the developing fetus and child.

What this study adds

There have been relatively few studies examining the association between binge‐drinking and pregnancy and child outcomes.

There was no consistent evidence of adverse effects across different studies.

There is evidence of a possible effect on neurodevelopmental outcome but further research is required to confirm this.

The table is available on the JECH website at http://jech.bmj.com/supplemental

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work formed part of a Department of Health commissioned review into the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. The National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit is funded by the Department of Health. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Health. We are grateful to our colleagues at the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit and to the project advisory group for their helpful input throughout this project.

Appendix 1

Medline search strategy.

| #22 | (#19 not #20) and (LA:MEDS = ENGLISH) and (PY:MEDS > = 1970) and (TG:MEDS = HUMANS) | 598 |

| #21 | #19 not #20 | 639 |

| #20 | (risk.mp or explode cohort studies/all subheadings or between groups.tw.) and (((low or light or social or moderate or dose or bing*) and ((explode “Alcohol‐Related‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Alcohol‐Drinking”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Ethanol‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or alcohol* or drinking)) and (#15 or #14 or #11 or #10 or #9 or #8 or #7 or #6 or #5 or #4)) and ((PT:MEDS = CASE‐REPORTS) or (PT:MEDS = EDITORIAL) or (PT:MEDS = LETTER) or (PT:MEDS = REVIEW)) | 35 |

| #19 | (risk.mp or explode cohort studies/all subheadings or between groups.tw.) and (((low or light or social or moderate or dose or bing*) and ((explode “Alcohol‐Related‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Alcohol‐Drinking”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Ethanol‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or alcohol* or drinking)) and (#15 or #14 or #11 or #10 or #9 or #8 or #7 or #6 or #5 or #4)) | 674 |

| #18 | risk.mp or explode cohort studies/all subheadings or between groups.tw. | 529208 |

| #17 | ((low or light or social or moderate or dose or bing*) and ((explode “Alcohol‐Related‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Alcohol‐Drinking”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Ethanol‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or alcohol* or drinking)) and (#15 or #14 or #11 or #10 or #9 or #8 or #7 or #6 or #5 or #4) | 4851 |

| #16 | #15 or #14 or #11 or #10 or #9 or #8 or #7 or #6 or #5 or #4 | 1000764 |

| #15 | (explode “Child‐Development‐Disorders‐Pervasive”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Child‐Language”/WITHOUT SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (((mental retard*) or (learning disabil*) or neuro?development* or wisc* or cbcl) or (explode “Mental‐Disorders‐Diagnosed‐in‐Childhood”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Child‐Development”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) | 180847 |

| #14 | #12 and #13 | 293325 |

| #13 | (((explode “Intelligence‐Tests”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Intelligence‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (brain imag*) or (explode “Diagnostic‐Imaging”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (neuro?behav*) or (explode “Neurobehavioral‐Manifestations”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Psychophysiology‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Psychological‐Tests”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or ((explode “Motor‐Activity”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Hyperkinesis‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Psychomotor‐Performance”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME))) or ((explode “Motor‐Skills”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Motor‐Skills‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) or ((explode “Language‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Language‐Development”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Language‐Development‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) or (executive function*) or ((explode “Memory‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Memory‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) or ((explode “Learning‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Learning‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) or ((explode “Attention‐Deficit‐and‐Disruptive‐Behavior‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Attention‐Deficit‐Disorder‐with‐Hyperactivity”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Attention‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME))) or (cognit*) or ((explode “Cognition‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Cognition‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME)) | 1763936 |

| #12 | neonat* or prenat* or infant* or child* | 1802707 |

| #11 | (explode “Fetal‐Alcohol‐Syndrome”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (f?etal alcohol) or (alcohol embryopathy) | 2883 |

| #10 | (explode “Abnormalities‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (congenital anomal*) or malformation* or (birth defect*) or microcephaly or (head circumference) | 318497 |

| #9 | (explode “Birth‐Weight”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or ((birth?weight) or (birth weight) or ((explode “Fetal‐Growth‐Retardation”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Growth‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (growth restrict*) or (growth retard*) or (small for gestational age) or (low birth weight) or (antepartum h?emorrhage) or sga or lbw or elbw or vlbw or iugr)) | 74747 |

| Searches and results below from saved search history final medline | ||

| #8 | (gestation*) or (explode “Gestational‐Age”/WITHOUT SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or ((explode “Labor‐Premature”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Infant‐Premature”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Fetal‐Membranes‐Premature‐Rupture”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Premature‐Birth”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Infant‐Premature‐Diseases”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or prematur* or preterm*) | 206714 |

| #7 | neonatal death* | 2939 |

| #6 | (explode “Fetal‐Death”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (fetal loss*) or stillbirth* | 23871 |

| #5 | (explode “Pregnancy‐Complications”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Pregnancy‐Outcome”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) | 231043 |

| #4 | (explode “Abortion‐Spontaneous”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or miscarriage* or (spontaneous abortion*) | 26183 |

| #3 | (low or light or social or moderate or dose or bing*) and ((explode “Alcohol‐Related‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Alcohol‐Drinking”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Ethanol‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or alcohol* or drinking) | 66108 |

| #2 | low or light or social or moderate or dose or bing* | 2080332 |

| #1 | (explode “Alcohol‐Related‐Disorders”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Alcohol‐Drinking”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or (explode “Ethanol‐”/all SUBHEADINGS in MIME,MJME) or alcohol* or drinking | 271952 |

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

The table is available on the JECH website at http://jech.bmj.com/supplemental

References

- 1.Stratton K R, Howe C J, Battaglia F C.Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention and Treatment. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1996

- 2.Abel E L.Fetal Alcohol Abuse Syndrome. New York: Plenum Press, 1998

- 3.Bonthius D J, Goodlett C R, West J R. Blood alcohol concentration and severity of microencephaly in neonatal rats depend on the pattern of alcohol administration. Alcohol 19885209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health The Pregnancy Book London: The Stationery Office 2005

- 5.Rickards L, Fox K, Roberts C.et al eds. Living in Britain: Results from the General Household Survey, no 31. London: The Stationery Office 2004

- 6.Nulman I, Rovet J, Kennedy D.et al Binge alcohol consumption by non‐alcohol‐dependent women during pregnancy affects child behaviour, but not general intellectual functioning; a prospective controlled study. Arch Womens Mental Health 20047173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kesmodel U. Binge drinking in pregnancy—frequency and methodology. Am J Epidemiol 2001154777–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey B N, Delaney Black V.et al Prenatal exposure to binge drinking and cognitive and behavioral outcomes at age 7 years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 20041911037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray R, Henderson J. Report to the Department of Health—Review of the fetal effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit 2006

- 10.Wilczynski N, Haynes R, Hedges Team Developing optimal search strategies for detecting clinically sound causation studies in MEDLINE. AMIA Ann Symposium Proceed 20032003719–723. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells G A, Shea B, O'Connell D.et al The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non‐randomised studies in meta‐analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm (accessed Jan 2006)

- 12.Streissguth A, Barr H, Martin D. Maternal alcohol use and neonatal habituation assessed with the Brazelton Scale. Child Develop 1983541109–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streissguth A P, Barr H M, Sampson P D.et al Neurobehavioral effects of prenatal alcohol: Part I. Research strategy. Neurotoxicol Teratol 198911461–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streissguth A P, Barr H M, Sampson P D. Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure: effects on child IQ and learning problems at age 7 1/2 years. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 199014662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampson P, Bookstein F, Barr H.et al Prenatal alcohol exposure, birthweight, and measures of child size from birth to age 14 years. Am J Public Health 1994841421–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plant M, Plant M. Maternal use of alcohol and other drugs during pregnancy and birth abnormalities: further results from a prospective study. Alcohol Alcohol 198823229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Passaro K T, Little R E, Savitz D A.et al The effect of maternal drinking before conception and in early pregnancy on infant birthweight. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Epidemiology 19967377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell R, Lumley J. Alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking and fetal outcome in Victoria, 1985. Community Health Stud 198913484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tolo K A, Little R E. Occasional binges by moderate drinkers: implications for birth outcomes. Epidemiology 19934415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitehead N, Lipscomb L. Patterns of alcohol use before and during pregnancy and the risk of small‐for‐gestational‐age birth. Am J Epidemiol 2003158654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Callaghan F V, O'Callaghan M, Najman J M.et al Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy and physical outcomes up to 5 years of age: a longitudinal study. Early Hum Dev 200371137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen J, Tuntiseranee P. Is moderate alcohol intake in pregnancy associated with the craniofacial features related to the fetal alcohol syndrome? Scand J Soc Med 199523156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen J. Effects of moderate alcohol consumption during pregnancy on child development at 18 and 42 months. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1994181109–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adab N, Tudur Smith C, Vinten J.et al Common antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004; Issue 3. Art. No. : CD004848, DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004848 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kesmodel U, Kesmodel P S, Larsen A.et al Use of alcohol and illicit drugs among pregnant Danish women, 1998. Scand J Public Health 2003315–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson S W, Jacobson J L, Sokol R J.et al Maternal recall of alcohol, cocaine and marijuana use during pregnancy. Neurotoxicol Teratol 199113535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verkerk P H. The impact of alcohol misclassification on the relationship between alcohol and pregnancy outcome. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21(4 Suppl. 1)S33–S37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Plant M, Plant M.Binge Britain: Alcohol and the National Response. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.