Abstract

Objective

To investigate associations between neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors (i.e. experience of crime, nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, youngsters frequently hanging around, rubbish on the streets, feeling unsafe and dissatisfaction with the quality of green space) and self‐rated health in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Participants

A random sample of 2914 subjects aged ⩾ 18 years from 75 neighbourhoods in the city of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Design

Individual data from the Social State of Amsterdam Survey 2004 were linked to data on neighbourhood‐level attributes from the Amsterdam Living and Security Survey 2003. Multilevel logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios and neighbourhood‐level variance.

Results

Fair to poor self‐rated health was significantly associated with neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors: nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, youngsters frequently hanging around, rubbish on the streets, feeling unsafe and dissatisfaction with green space. In addition, when all the neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors were combined, individuals from neighbourhoods with a high score of psychosocial stressors were more likely than those from neighbourhoods with a low score to report fair to poor health. These associations remained after adjustments for individual‐level factors (i.e. age, sex, educational level, income and ethnicity). The neighbourhood‐level variance showed significant differences in self‐rated health between neighbourhoods independent of individual‐level demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Conclusion

Our findings show that neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors are associated with self‐rated health. Strategies that target these factors might prove a promising way to improve public health.

Keywords: self‐rated health, neighbourhood psychosocial stressor, multilevel, the Netherlands

In the past few years, interest in neighbourhood effects on health has increased tremendously. Evidence strongly indicates that the neighbourhood in which people live influences their health, either in addition to or in interaction with individual‐level characteristics.1,2 A recent systematic review of multilevel studies,1 for example, showed fairly consistent and modest neighbourhood effects on health despite differences in study designs, neighbourhood measures and possible measurement errors.

The explanation for the relative bad health of people living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods is the subject of intense debate. There are two main interpretations: a psychosocial perspective and a neomaterial perspective. According to the proponents of the psychosocial theory, stressors in the neighbourhood make residents feel unpleasant, and this affects their behaviour (inappropriate coping strategies) and biology (psycho‐neuroendocrine mechanisms), which, in turn, increase their susceptibility to diseases in addition to the direct effects of absolute material living standards.3,4,5,6,7,8 A negative neighbourhood climate characterised by heightened fear and exposure to crime has been shown to be associated with poor health outcomes.7,8,9,10,11,12,13 This psychosocial approach suggests that health can be promoted by improving neighbourhood psychosocial environment, for example, by reducing crime or drug misuse.

According to the neomaterial theory, the impaired health of residents of certain neighbourhoods results from the accumulation of exposure and experiences that have their roots in the material world.14,15,16,17,18 The health effects of being deprived of an array of material goods are the consequence of a combination of exposure to material deprivation and a lack of individual economic resources associated with a systematic low investment in a range of human, physical, health and social infrastructures.14 The unequal distribution of neighbourhood income is the result of historical, cultural, political and economic processes. These processes influence the availability of private resources to individuals and also determine public infrastructure in areas such as education and health care services, availability of food, transport, control of the environment, quality of housing and rules and regulations in the workplace.14 According to the neomaterial perspective, health can be promoted through reflection on the structural determinants that condition inequality of income, such as residential segregation and unemployment.

Several studies have examined the influence of neighbourhood‐level factors on self‐rated health.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 Most of these studies were focused on material conditions underlying the health disadvantage. They indicate that neighbourhood‐level deprivation,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 lower socioeconomic status,20,25,26 poor quality of the physical residential environment and lower transport wealth26 are associated with fair to poor self‐rated health. Although it is suggested that the features of neighbourhoods may also affect health through psychosocial pathways, only a small number of studies have examined the associations of neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors and self‐rated health.26,31,36 The results of these studies have not been consistent. For example, Cummins and colleagues26 found no association between neighbourhood crime and self‐rated health. Steptoe and Feldman31, however, found perceived neighbourhood problems to be associated with poor self‐rated health.

Also, in the Netherlands, recent studies show clear associations between self‐rated health and neighbourhood‐level deprivation, indicating the importance of material influences on health.19,20,37 As in other countries, however, it is unclear whether the psychosocial perspective is relevant at this level as well. It is possible that residential neighbourhood problems may constitute sources of chronic stress, which may increase the risk of poor perceived health.31,34 The main objective of this paper was to assess the associations between neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors and self‐rated health in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. We tested the importance of each neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressor (i.e. crime, nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, noise, rubbish on the street, graffiti, youngsters hanging around or feeling unsafe, dissatisfaction with green space and unemployment/social benefit) on self‐rated health controlling for material factors at the individual level. In addition, we also determined whether self‐rated health varies across neighbourhoods and the extent to which each psychosocial factor contributed to that variation. The estimation of measures of neighbourhood variance is of great importance and complements the information obtained by classical measures of associations.38,39

Data and methods

The data for this study came from two different sources. The individual (first) level data included information on demographics, socioeconomic status (household income and education level) and self‐rated health. The contextual (second) level data included information on aggregated neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors. These two levels were linked by neighbourhood, creating a multilevel design for data analysis.

Data collection at the individual level

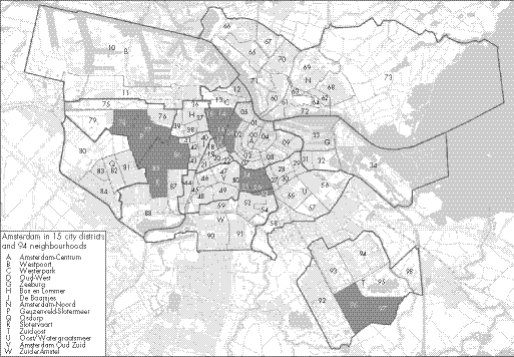

The individual‐level data were provided by the Department of Research and Statistics of Amsterdam Municipality (Dienst Onderzoek en Statistiek (O+S)) based on the State of the City of Amsterdam Survey. This cross‐sectional study was carried out in 2004 by O+S to monitor the participation and living conditions in the Amsterdam general population aged ⩾ 18 years. A proportional random sample was drawn from the Amsterdam municipal registers in 14 city districts in Amsterdam (figure 1). The data were collected by means of three different survey methods: postal questionnaires, telephone interviews and face‐to‐face interviews. The data obtained from face‐to‐face interviews (275 individuals) were excluded from the analyses because of possible response bias. A further 268 participants were excluded because of small neighbourhood sample size (< 10 subjects in a neighbourhood (n = 14 neighbourhoods)), and missing data on gender, age, educational level, ethnicity or self‐rated health. Data analyses were performed on the remaining 2914 participants from 75 neighbourhoods. Of the 2914 participants included in our analyses, 65% were interviewed by postal survey and 35% by telephone. The average number of participants per neighbourhood was 50, ranging from 11 to 120. Women were slightly better represented than men.

Figure 1 Map of city districts and neighbourhoods of Amsterdam.

Individual‐level variables

Self‐rated health

Self‐rated health was asked in a single question – “How is your health in general?” – and included five answer categories: excellent, very good, good, fair and poor. Responses were dichotomised by assigning 0 to those who answered excellent to good and 1 to those responding fair or poor. Self‐rated health is considered a valid and robust measure of general health status. It is a strong and independent predictor of morbidity and mortality.40

Ethnic groups were classified according to the self‐reported country of birth and/or the country of birth of the respondent's mother or father in accordance with the Netherlands Central Bureau of Statistics.41

Education level was divided into three categories (primary school and below (low), lower secondary school or vocational school to intermediate vocational school or intermediate/higher secondary school (middle) and higher vocational school and university (high)).

Income was determined by a self‐reported monthly income and was divided into two categories < 1000 euros (low) and ⩾ 1000 euros (high).

Neighbourhood‐level data

The contextual level variables were also provided by O+S Amsterdam, based on the Amsterdam Living and Security Survey 2003. This was a large cross‐sectional study (n = 9955) which was carried out in 2003 by O+S to assess the safety and security situation of the Amsterdam general population aged ⩾ 18 years.42 Information on psychosocial stressors was calculated for each neighbourhood. In the Netherlands, neighbourhoods are areas with a similar type of building, often delineated by natural boundaries. As a result, they are socioculturally quite homogeneous. The population size varies greatly by neighbourhood.19

Neighbourhood‐level variables

Crime

Experience of crime was based on the proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported having experienced crime (such as break‐ins, theft, aggravated assault, vandalism or a stolen purse) in their own neighbourhood in the past 12 months.

Nuisance from drug misuse

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being bothered by frequent drug misuse.

Nuisance from youngsters hanging around

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being bothered by youngsters hanging around regularly.

Rubbish on the street

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported rubbish on the streets.

Graffiti

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported graffiti on the walls.

Feel unsafe

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported feeling unsafe regularly.

Nuisance from noise

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being bothered by noise.

Nuisance from neighbours

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being frequently bothered by the neighbours in their neighbourhood.

Dissatisfaction with green space

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being dissatisfied with the quality of green space in their neighbourhood.

Unemployment/social benefit

The proportion of people in each neighbourhood who reported being unemployed or who were receiving social benefit.

Neighbourhoods were divided into three equal‐sized groups (tertiles) for each neighbourhood‐level factor. Tertile 1 represented neighbourhoods with the lowest proportion of the neighbourhood factor and tertile 3 represented neighbourhoods with the highest proportion of the neighbourhood factor.

Data analysis

We performed a multilevel logistic regression to determine the associations between neighbourhood‐level factors and self‐rated health with individuals at the first level and neighbourhoods at the second level using the SAS GLIMMIX macro procedure (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Each neighbourhood‐level stressor was modelled separately because of high correlations between neighbourhood‐level stressors (table 1). In addition, we created summary scores for all the neighbourhood psychosocial stressors for each neighbourhood. The results are shown as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The method of estimation was a restricted maximum likelihood procedure. We performed three models to determine the associations between neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors and self‐rated health adjusting for potential confounding factors. Model 1 included each neighbourhood variable and the individual‐level variables age and sex. In model 2 the same variables were included but in addition the individual‐level variables education level and income were added to determine whether the differences were independent of individual‐level socioeconomic status. In model 3 the same variables were included but in addition the individual‐level variable ethnic background was added. Ethnicity was included in the final model because recent evidence in The Netherlands suggests that different ethnic groups might interpret the perception of self‐perceived health differently.43 We calculated the intraclass correlation (ICC) to estimate the proportion of total variation in self‐rated health that occurred at the neighbourhood level, using the latent variable method.44 In addition, we calculated the median odds ratio (MOR), which has a consistent and intuitive interpretation.45,46 MOR quantifies cluster variance in terms of odds ratios. It is therefore comparable to the fixed effects odds ratio, which is the most widely used measure of effect for dichotomous outcomes.

Table 1 Correlation matrix for neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressor variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Experience of crime | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 2 Nuisance from neighbours | 0.042* | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 3 Nuisance from drugs | 0.263*** | 0.461*** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4 Nuisance from noise | 0.376*** | 0.413*** | 0.688*** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5 Rubbish on the street | 0.377*** | 0.594*** | 0.484*** | 0.559*** | 1.000 | |||||

| 6 Graffiti | 0.533*** | 0.243*** | 0.548*** | 0.592*** | 0.507*** | 1.000 | ||||

| 7 Youngsters hanging around | 0.073*** | 0.513*** | 0.381*** | 0.280*** | 0.449*** | 0.070*** | 1.000 | |||

| 8 Feeling unsafe | 0.400*** | 0.419*** | 0.358*** | 0.448*** | 0.658*** | 0.443*** | 0.594*** | 1.000 | ||

| 9 Unemployed/receiving social benefit | 0.086** | 0.521*** | 0.266*** | 0.136*** | 0.285*** | 0.110*** | 0.019 | −0.026 | 1.000 | |

| 10 Dissatisfaction with green space | 0.391*** | 0.234*** | 0.429*** | 0.571*** | 0.419*** | 0.541*** | 0.006 | 0.204*** | 0.241*** | 1.000 |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Results

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study population. About 17% of the respondents reported fair to poor health.

Table 2 Characteristics of the study population.

| Number of participants | 2914 |

| Number of neighbourhoods | 75 |

| Mean (min–max) number of participants per neighbourhood | 50 (11–120) |

| Individual‐level data | |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 44.0 (15.6) |

| Women (%) | 57.2 |

| Ethnic groups (%) | |

| Dutch | 69.0 |

| Surinamese | 7.8 |

| Antilleans | 1.1 |

| Turkish | 2.7 |

| Moroccan | 2.0 |

| Other | 17.4 |

| Education level (%) | |

| Low | 29.7 |

| Middle | 24.0 |

| Higher | 46.2 |

| Income (%) | |

| < 1000 euros | 16.7 |

| > 1000 euros | 83.3 |

| Fair to poor health (%) | 16.9 |

Table 3 shows the association between each neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressor and fair to poor self‐rated health in three different models. A significantly increased risk of reporting fair to poor self‐rated health was observed for people living in neighbourhoods with medium to high proportions of nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, rubbish on the streets, youngsters regularly hanging around, unemployment/social benefit and feeling unsafe in their own neighbourhoods. These associations were attenuated, but remained, after further adjustments for individual‐level socioeconomic status and ethnicity, although neighbourhoods with medium levels of nuisance from neighbours and rubbish on the streets were of borderline significance in the full model. Neighbourhood dissatisfaction with quality of green space was associated with fair to poor self‐rated health, although the difference was significant only for the low versus medium levels. There were no significant associations between neighbourhood experience of crime, graffiti or nuisance from noise and self‐rated health. In addition, when all the neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors were combined, participants from neighbourhoods with a high score of psychosocial stressors were more likely than those from neighbourhoods with a low score to report fair to poor health, the differences still remaining after adjustments for individual‐level variables. The trends in the effects of neighbourhood psychosocial stressors on fair to poor health were of similar magnitude.

Table 3 Odds ratios (and 95% confidence interval (CIs)) for self‐reporting fair to poor health by neighbourhood‐level stressor.

| Neighbourhood stressor | Model 1: age and sex adjusted | Model 2: adjusted for age, sex education level and income | Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, education level, income and ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crime | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 0.70 (0.48 to 1.07) | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.04) | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.08) |

| High | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.23) | 0.86 (0.59 to 1.25) | 0.92 (0.64 to 1.31) |

| Nuisance from neighbours | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.38 (1.06 to 1.96)* | 1.39 (0.99 to 1.95) | 1.36 (0.97 to 1.89) |

| High | 2.55 (1.86 to 3.49)*** | 2.16 (1.54 to 3.03)*** | 1.99 (1.43 to 2.78)*** |

| Nuisance from drug misuse | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.30)** | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.28)** | 1.49 (1.05 to 2.12)* |

| High | 1.68 (1.17 to 2.40)** | 1.66 (1.17 to 2.35)** | 1.59 (1.13 to 2.23)** |

| Nuisance from noise | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Med | 1.30 (0.89 to 1.90) | 1.30 (0.90 to 1.88) | 1.24 (0.87 to 1.76) |

| High | 1.35 (0.92 to 1.99) | 1.36 (0.94 to 1.99) | 1.30 (0.91 to 1.88) |

| Rubbish on the street | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.42 (1.00 to 2.03)* | 1.41 (1.00 to 2.00)* | 1.41 (0.99 to 2.00) |

| High | 1.68 (1.17 to 2.42)*** | 1.68 (1.17 to 2.40)** | 1.68 (1.17 to 2.40)** |

| Graffiti | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.37 (0.95 to 1.97) | 1.37 (0.96 to 1.95) | 1.31 (0.93 to 1.84) |

| High | 1.18 (0.80 to 1.97) | 1.19 (0.84 to 1.73) | 1.15 (0.81 to 1.64) |

| Youngsters hanging around | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.41 (0.97 to 2.03) | 1.40 (0.97 to 2.01) | 1.35 (0.95 to 1.91) |

| High | 1.76 (1.23 to 2.52)** | 1.73 (1.21 to 2.46)** | 1.62 (1.15 to 2.28)** |

| Feeling unsafe | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.23 (0.85 to 1.77) | 1.22 (0.85 to 1.76) | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.65) |

| High | 1.53 (1.06 to 2.20)* | 1.50 (1.05 to 2.16)* | 1.47 (1.05 to 2.07)* |

| Dissatisfaction with green space | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.65 (1.07 to 2.53)* | 1.66 (1.10 to 2.55)** | 1.64 (1.11 to 2.44)** |

| High | 1.20 (0.83 to 1.73) | 1.22 (0.85 to 1.74) | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.72) |

| Unemployed/receiving social benefit | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.46 (1.00 to 2.12)* | 1.45 (1.01 to 2.08)* | 1.35 (0.96 to 1.90) |

| High | 1.57 (1.09 to 2.26)* | 1.56 (1.10 to 2.22)** | 1.51 (1.09 to 2.10)** |

| All stressors combined | |||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Medium | 1.34 (0.93 to 1.94) | 1.33 (0.93 to 1.91) | 1.29 (0.91 to 1.83) |

| High | 1.66 (1.88 to 2.34)** | 1.65 (1.18 to 2.32)** | 1.54 (1.11 to 2.14)** |

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; all models are adjusted for survey type.

Table 4 shows the variation in fair to poor self‐rated health across neighbourhoods in Amsterdam (i.e. the random intercept). The variation in self‐rated health between neighbourhoods was statistically significant. These differences persisted even after adjustment for individual‐level differences in age, sex, socioeconomic status and ethnicity. Six per cent of the total variation in self‐rated health was between neighbourhoods. Adjustments for individual‐level socioeconomic status and ethnicity reduced between neighbourhood variations to 4.6%. Adjustment for each neighbourhood‐level stressor further reduced the variation between neighbourhoods, except for crime. Adjustment for nuisance from neighbours had the biggest impact, reducing the between‐neighbourhood variation to 2.8%.

Table 4 Variation in fair to poor self rated health across neighbourhoods in Amsterdam.

| Neighbourhood variance (SE) | ICC | MOR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base model: age and sex adjusted | 0.208 (0.072)** | 0.060 | 1.55 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status† | 0.203 (0.071)** | 0.058 | 1.54 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status and ethnicity | 0.160 (0.065)* | 0.046 | 1.47 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + crime | 0.158 (0.065)* | 0.046 | 1.46 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + nuisance from neighbours | 0.094 (0.051) | 0.028 | 1.34 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + nuisance from drug misuse | 0.123 (0.059)* | 0.036 | 1.40 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + nuisance from noise | 0.149 (0.064)* | 0.043 | 1.45 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + more rubbish on the street | 0.148 (0.063)* | 0.043 | 1.44 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + graffiti | 0.145 (0.064)* | 0.042 | 1.43 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + youngsters hanging around | 0.124 (0.058)* | 0.036 | 1.40 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity feeling unsafe | 0.129 (0.061)* | 0.038 | 1.41 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status ethnicity + dissatisfaction with green space | 0.124 (0.060)* | 0.036 | 1.40 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + unemployment/social benefit | 0.124 (0.056)* | 0.036 | 1.40 |

| Adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, ethnicity + all stressors combined§ | 0.114 (0.059) | 0.035 | 1.38 |

ICC (intraclass correlation coefficient, i.e. the proportion of the total variance in self‐rated health that is between neighbourhoods) is estimated as σu02/(σu02 + π2/3) and ranges from 0 (no differences in self‐rated health between neighbourhoods) to 1 (all variation is at the neighbourhood level). MOR (median odd ratio) is estimated as exp(√(2 × σ2) × Φ–1(0.75)); p<0.05, **p<0.01; all models are adjusted for survey type; † (socioeconomic status was determined by education level and income); SE, standard error.

The neighbourhood variance corresponds well to the MOR values.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that neighbourhoods with high levels of nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, youngsters frequently hanging around and rubbish on the streets were associated with fair to poor perceived health among their inhabitants. These associations remained after adjustments for individual‐level socioeconomic status. The study findings also show clear neighbourhood differences in self‐rated health. These differences persisted after adjustment for differences in individual‐level demographic and socioeconomic factors. Specific psychosocial stressors at the neighbourhood level contributed to the variation between neighbourhoods in self‐rated health.

Some limitations must be acknowledged. Interviews were carried out by postal survey and telephone. It is possible that people might respond differently to questions on paper than to questions asked by an interviewer on the phone. In this study, individuals interviewed by postal surveys were more likely than those interviewed by telephone surveys to report fair to poor health (p = 0.01). Nevertheless, applying both postal and telephone interviews was necessary to increase participation and it is an adequate procedure to obtain information of good quality.47 We controlled for the survey methods in all the analyses. It is therefore unlikely that these differences in survey methods could bias the study conclusions. We were unable to equalise household income because of lack of information on the number of people in each household who had an income. A monthly income of 1500 euros for a household of three people, for example, is not the same as for a household of six people, and this may possibly affect our study conclusions. In addition, our neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors were not adjusted for neighbourhood‐level socioeconomic factors such as the percentage of people with a low education level and income, which may also affect our study conclusions. However, after further adjustment for neighbourhood‐level unemployment/social benefit (also an indicator of neighbourhood socioeconomic status), people living in neighbourhoods with high proportions of nuisance from neighbours (OR = 2.14; 95% CI 1.46 to 1.93), drug misuse (OR = 1.52; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.13), rubbish on the streets (OR = 1.57; 95% CI 1.09 to 2.26) and youngsters regularly hanging around (OR = 1.60; 95% CI 1.14 to 2.25) were still associated with fair to poor self‐rated health. More studies are needed to confirm these findings. The study sample was limited to the Amsterdam population, which makes it somewhat difficult to generalise the results to the whole of the Netherlands. Also, 14 neighbourhoods were excluded from the analyses because of the low number of respondents in these neighbourhoods. It is possible that these excluded neighbourhoods might differ from the included 75 neighbourhoods, which might affect our study conclusions. A further limitation was the cross‐sectional nature of the study design, which is limited in its ability to pin down the direction of causality. More recently, Oakes48 has raised a series of important questions on the validity of observational approaches in research on neighbourhoods and health and suggested randomised community trials as an alternative. Nevertheless, as emphasised by others,49,50,51 and also acknowledged by Oakes,48 randomised community trials have their own sets of limitations. For many neighbourhood factors of interest, it is impossible to design a randomised community trial and to obtain evidence on the effect of a single factor.49

A strength of this study is that it is one of the few studies, and the first in the Netherlands, to assess associations between neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors and self‐perceived health. The neighbourhoods considered in our study are socioculturally rather homogeneous communities. It has been emphasised that contextual or area bound factors may have a greater impact on health if a neighbourhood relates to a socioculturally homogeneous community.19 The neighbourhood‐level variance showed significant differences in self‐rated health between neighbourhoods in Amsterdam even after adjusting for individual‐level demographic and socioeconomic variables. This study finding is consistent with several studies,19,20,27,30,35 including earlier studies on neighbourhood deprivation and self‐rated health in the Netherlands.19,20 The findings of associations between neighbourhood psychosocial stressors and self‐rated health in our study add to the existing literature documenting an association between neighbourhood attributes and health.19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 A small number of studies have focused on neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors.26,30,31,32 Our study provides further evidence on the associations between these stressors and self‐rated health independent of individual‐level demographic and socioeconomic factors. Our findings provide support for the psychosocial perspective and are consistent with other studies that have demonstrated associations between neighbourhood‐level psychosocial factors and other health outcomes.3,8,26,30,31

There are several mechanisms through which neighbourhood psychosocial stressor may be linked to poor health. For example, neighbourhoods that score high on perceived fear of victimisation (such as frequently feeling unsafe as a result of youngsters hanging around) may discourage residents from engaging in healthy lifestyle measures such as physical activity, which, in turn, may lead to poor health. In addition, a poor quality of the neighbourhood built environment, such as unsatisfactory green space, may also discourage residents from engaging in outdoor recreation, which in turn may lead to unhealthy lifestyles. In our study, dissatisfaction with neighbourhood green space was associated with a higher risk of fair to poor self‐rated health. Takano et al52 also found that living in a neighbourhood with greenery‐filled public areas positively influenced the longevity of urban senior citizens. It has been shown that a significant portion of physical health differentials across neighbourhoods is due to stress level differences across neighbourhoods.36 It is possible that the biological pathway between neighbourhood environment and poor health may be mediated by an abnormal neuroendocrine secretory pattern53 due to stress. Chronic activation of the stress system is believed to lead to allostasis or allostatic load (i.e. wear and tear on organ systems), which may have harmful effects on health.54

Our finding of a lack of association between experience of crime and self‐rated health is surprising, but consistent with Cummins and colleagues' study from England.26 It is in contrast with the strong associations reported between neighbourhood crime and other health outcomes. For example, a recent study from Sweden showed a positive association between neighbourhood crime and coronary heart disease even after controlling for the individual‐level factors.55 Agyemang and colleagues'56 recent study found a positive association between neighbourhood crime and blood pressure in Amsterdam. In addition, Morenoff57 found that the neighbourhood violent crime rate was one of the most robust environmental predictors of infant birthweight, after controlling for both individual‐ and neighbourhood‐level characteristics. The reasons for these inconsistent results are unclear. However, it might well be that perception of general health is influenced more by the fear of crime or victimisation rather than experience of crime. A perception of crime and disorder within an individual's community has been associated with numerous outcomes, including anxiety, depression and post‐traumatic stress disorder.58,59,60 It is also possible that the discrepancies between our results and those reported elsewhere may be due to a difference in neighbourhood definition and the spatial scale at which exposure was measured. The stronger association between neighbourhood nuisance and self‐rated health than other neighbourhood attributes might reflect the importance of social cohesion and trust on health.9 Stafford and colleagues30 also found neighbourhoods with low levels of trust or tolerance of neighbours to be strongly associated with fair to poor self‐rated health. It is possible that nuisance from neighbours might increase the negative effects of neighbourhood problems more than other neighbourhood factors we considered, with greater consequence on health.58

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors are related to fair to poor perceived health independent of individual‐level demographics. These findings provide indications to suggest that strategies that target these neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors might prove a promising way to improve public health. For example, promotion of neighbourhood social relations, clean streets, and discouragement of drug misuse might provide additional benefit in improving the general health of disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

What is already known on this subject

The neighbourhood in which people live influences their health.

What this paper adds

Neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors, in particular nuisance from neighbours, drug misuse, youngsters frequently hanging around, rubbish on the streets and unemployment/social benefit, are associated with fair to poor self‐rated health in Amsterdam.

Policy implications

Strategies that target these neighbourhood‐level psychosocial stressors might prove a promising way to improve public health.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the five referees who provided comments that helped to improved an earlier version of this paper. We also thank A. de Jonge (TNO, Leiden, the Netherlands) for her very useful comments, which helped to improve an earlier version of this paper.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Pickett K E, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health 200155111–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kamp I, van Loon J, Droomers M.et al Residential environment and health: a review of methodological and conceptual issues. Rev Environ Health 200419381–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Bosma H, Hemingway H.et al Contribution of job control and other risk factors to social variations in coronary heart disease incidence. Lancet 1997350235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilkinson R G.Unhealthy societies: the afflictions of inequality. London: Routledge, 1996

- 5.Wilkinson R G. Health, hierarchy and social anxiety. Ann NY Acad Sci 199989648–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson R. Inequality and the social environment: a reply to Lynch. J Epidemiol Community Health 200054411–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkinson R, Kawachi I, Kennedy B. Mortality, the social environment, crime and violence. Sociol Health Illn 199820578–597. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ 20013221233–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, eds. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000174–190.

- 10.Kawachi I, Berkman L F.Neighbourhoods and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 200365–111.

- 11.Wilkinson R G. The epidemiological transition: from material society to social disadvantage? Daedalus 199412361–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawachi I, Kennedy B P. Socioeconomic determinants of health: health and social cohesion: why care about income inequality? BMJ 19973141037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waitzman N J, Smith K R. Separate but lethal: the effects of economic segregation on mortality in metropolitan America. Milbank Q 199876341–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Kaplan G.et al Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychosocial environment or material conditions. BMJ 20003201200–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch J, Davey Smith G, Harper S.et al Is income inequality a determinant of population health? Part 1. A systematic review. Milbank Q 2004825–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muntaner C, Lynch J, Hillemeier M.et al Economic inequality, working‐class power, social capital, and cause‐specific mortality in wealthy countries. Int J Health Serv 200232423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turrell G. Income inequality and health: In search of fundamental causes. In: Eckersley R, Dixon J, Douglas R, eds. The social origins of health and well‐Being. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 200183–104.

- 18.Muntaner C. Commentary: social capital, social class, and the slow progress of psychosocial epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 200433674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reijneveld S A, Verheij R A, Bakker D H. The impact of area deprivation on differences in health: does the choice of the geographical classification matter? J Epidemiol Community Health 200054306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reijneveld S A. Neighbourhood socio‐economic context and self‐reported health and smoking: a secondary analysis of data on seven cities. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmstrom M, Sundquist J, Johansson S E. Neighborhood environment and self‐reported health status: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health 1999891181–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavanagh A M, Turrell G, Subramanian S V. Does area‐based social capital matter for the health of Australians? A multilevel analysis of self‐rated health in Tasmania. Int J Epidemiol 200635607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen M, Browning C R, Cagney K A. Poverty, affluence, and income inequality: neighborhood economic structure and its implications for health. Soc Sci Med 200357843–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzini L, Caughy M, Spears W.et al Neighborhood economic conditions, social processes, and self‐rated health in low‐income neighborhoods in Texas: a multilevel latent variables model. Soc Sci Med 2005611135–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stafford M, Marmot M. Neighbourhood deprivation and health: does it affect us all equally? Int J Epidemiol 200332357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummins S, Stafford M, Macintyre S.et al Neighbourhood environment and its association with self rated health: evidence from Scotland and England. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stafford M, Martikainen P, Lahelma E.et al Neighbourhoods and self rated health: a comparison of public sector employees in London and Helsinki. J Epidemiol Community Health 200458772–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlsen S, Nazrooa J Y, Stephenson R. Ethnicity, environment and health: putting ethnic inequalities in health in their place. Soc Sci Med 2002551647–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browning C R, Cagney K A. Neighborhood structural disadvantage, collective efficacy, and self‐rated physical health in an urban setting. J Health Soc Behav 200243383–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stafford M, Cummins S, Macintyre S.et al Gender differences in the associations between health and neighbourhood environment. Soc Sci Med 2005601681–1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steptoe A, Feldman P J. Neighbourhood problems as sources of chronic stress: development of a measure of neighbourhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann Behav Med 200123177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Browning C R, Cagney K A. Moving beyond poverty: neighborhood structure, social processes, and health. J Health Soc Behav 200344552–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Glass R. Social capital and self‐rated health: a contextual analysis. Am J Public Health 1999891187–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sampson R J, Raudenbush S W, Earls F. Neighborhood and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997277918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindstrom M, Moghaddassi M, Merlo J. Individual self‐reported health, social participation and neighbourhood: a multilevel analysis in Malmo, Sweden. Prev Med 200439135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boardman J D. Stress and physical health: The role of neighbourhoods as mediating and moderating mechanisms. Soc Sci Med 2004582473–2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drukker M, Van Os J. Mediators of neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation and quality of life. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 200338698–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merlo J. Multilevel analytical approaches in social epidemiology: measures of health variation compared with traditional measures of association. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357550–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H.et al A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health 200660290–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Idler E L, Benyami Y. Self rated health and mortality: a review of twenty‐seven community studies. J Health Social Behaviour 19973821–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Central Bureau of Statistics Standaarddefinitie van allochtonen. Index No. 10, CBS 200010–13.

- 42.Directie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid Gemeente Amsterdam: Veiligheidsrapportage Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Gemeente 2005

- 43.Agyemang C, Denktas S, Bruijnzeels M.et al Validity of the single‐item question on self‐rated health status in first generation Turkish and Moroccans versus native Dutch in the Netherlands. Public Health 2006120543–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snijders T A B, Bosker R J.Multilevel analysis: an introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1999

- 45.Larsen K, Merlo J. Appropriate assessment of neighborhood effects on individual health – integrating random and fixed effects in multilevel logistic regression. Am J Epidemiol 200516181–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larsen K, Petersen J H, Budtz‐Jorgensen E.et al Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics 200056909–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galobardes B, Sunyer J, Anto J M.et al Effect of the method of administration, mail or telephone, on the validity and reliability of a respiratory health questionnaire. The Spanish Centers of the European Asthma Study. J Clin Epidemiol 199851875–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oakes J M. The (mis)estimation of neighborhood effects: causal inference for a practicable social epidemiology. Soc Sci Med 2004581929–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diez Roux A V. Estimating neighborhood health effects: the challenges of causal inference in a complex world. Soc Sci Med 2004581953–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subramanian S V. The relevance of multilevel statistical methods for identifying causal neighborhood effects. Soc Sci Med 2004581961–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Merlo J, Chaix B. Neighbourhood effects and the real world beyond randomized community trials: a reply to Michael J Oakes. Int J Epidemiol 2006351361–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takano T, Nakamura K, Watanabe M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens' longevity in megacity areas: the importance of walkable green spaces. J Epidemiol Community Health 200256913–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosmond R, Wallerius S, Wanger P.et al A 5‐year follow‐up study of disease incidence in men with an abnormal hormone pattern. J Intern Med 2003254386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McEwen B S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann NY Acad Sci 199884033–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sundquist K, Theobald H, Yang M.et al Neighborhood violent crime and unemployment increase the risk of coronary heart disease: a multilevel study in an urban setting. Soc Sci Med 2006622061–2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agyemang C, van Hooijdonk C, Wendel‐Vos W.et al Ethnic differences in the effect of environmental stressors on blood pressure and hypertension in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 20077118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morenoff J D. Neighborhood mechanisms and the spatial dynamics of birth weight. Am J Sociol 2003108976–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ross C E, Jang S J. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. Am J Community Psychol 200028401–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ross C E, Reynolds J L, Geis K J. The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents' psychological wellbeing. Am Sociol Rev 200065581–597. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cutrona C E, Russell D W, Hessling R M.et al Personality processes and individual differences direct and moderating effects of community context on the psychological well‐being of African American women. J Pers Soc Psychol Psychology 2000791088–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]