Abstract

Background

In earlier studies, determinants of socioeconomic gradient in mobility have not been measured comprehensively.

Aim

To assess the contribution of chronic morbidity, obesity, smoking and physical workload to inequalities in mobility.

Methods

This was a cross‐sectional study on 2572 persons (76% of a nationally representative sample of the Finnish population aged ⩾55 years). Mobility limitations were measured by self‐reports and performance rates.

Results

According to a wide array of self‐reported and test‐based indicators, persons with a lower level of education showed more mobility limitations than those with a higher level. The age‐adjusted ORs for limitations in stair climbing were threefold in the lowest‐educational category compared with the highest one (OR 3.3 in men and 2.9 in women for self‐reported limitations, and 3.5 in men and 2.2 in women for test‐based limitations). When obesity, smoking, work‐related physical loading and clinically diagnosed chronic diseases were simultaneously accounted for, the educational differences in stair‐climbing limitations vanished or were greatly diminished. In women, obesity contributed most to the differences, followed by a history of physically strenuous work, knee and hip osteoarthritis and cardiovascular diseases. In men, diabetes, work‐related physical loading, musculoskeletal diseases, obesity and smoking contributed substantially to the inequalities.

Conclusions

Great educational inequalities exist in various measures of mobility. Common chronic diseases, obesity, smoking and workload appeared to be the main pathways from low education to mobility limitations. General health promotion using methods that also yield good results in the lowest‐educational groups is thus a good strategy to reduce the disparities in mobility.

Mobility is an essential part of functioning, and a vital element of independent living and quality of life.1,2 Inequalities in mobility have been amply studied3,4,5,6,7: those with lower socioeconomic status, measured either by education, occupation or income, have more mobility limitations than those with a higher status.

Not much is known, however, about the factors that mediate the effect of socioeconomic position on disability. Chronic diseases, detrimental health behaviours and adverse occupational exposures are known risk factors for disability.8,9,10 Being unequally distributed among the social classes,11,12,13 they serve as potential pathways through which socioeconomic status may influence disability.11,14,15,16,17 However, the evidence to support this is relatively scant. Lifetime occupational exposures, both physical and psychological, have been found to contribute to the social class differences in self‐reported locomotor disability in early old age.17 Smoking, alcohol use, physical activity and body mass index reduced socioeconomic disparities in functioning to some extent,14,16,18 with differential effect in men and women.15 Some studies suggest that adjusting for comorbidity has a negligible effect on disparities,19,20,21 whereas others point to a more marked impact.5,22 The major limitation of these studies is that they rely on self‐reported data on diseases. Because less‐educated persons more often under‐report chronic conditions than those with higher education,23 the effect of diseases on socioeconomic differences in functioning might be obscured. Furthermore, information is lacking on which specific diseases and behavioural factors contribute most to socioeconomic differences in functioning. The central challenge in reducing the socioeconomic disparities is to identify specific factors that can be intervened by health and social policy.

This study describes educational differences in a wide array of objectively measured and self‐reported mobility tasks in the general elderly population. The focus is on assessing the contribution of smoking and obesity, a history of physically strenuous work and specific clinically diagnosed chronic conditions to educational differences in mobility, by individually and sequentially controlling for these potential mediating factors.

Methods

Study population

The Health 2000 Survey was a comprehensive cross‐sectional health interview and examination survey conducted in 2000–1.24 The two‐stage stratified cluster sample represented the Finnish adult population. Subjects aged ⩾80 years were emphasised by doubling the sampling fraction. This study concerns persons aged ⩾55 years (n = 3392). Persons participating in the home‐based interview and clinic‐based examination were eligible for these analyses (1503 (73%) women, mean age 67.6 years; 1069 (80%) men, mean age 65.8 years).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Epidemiology and Public Health in the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa, Finland.

Education

Information on the level of general and vocational education was gathered in the interview and combined into three categories: low, primary school or less, no vocational training; intermediate, no general education beyond some secondary school combined with low vocational training/school, or secondary school with no vocational training beyond a basic course; high, matriculation examination, or secondary school with vocational school, or a degree from a vocational institute, polytechnic or university. The median years of schooling in low, intermediate and high levels of education were 6, 8 and 12 years, respectively. The proportion of women in low‐educational, intermediate‐educational and high‐educational groups was 28%, 51% and 21%, and in men it was 32%, 48% and 20%, respectively.

Mobility

The health interview included questions on moving about in the house, walking about 0.5 km without resting, running 100 m, walking 100 m while carrying a 5 kg bag, climbing up one flight of stairs without resting, riding a bicycle, and travelling by train, bus or tram. The respondents were classified as having limitations if they reported any difficulties or were unable to perform the activity. Mobility was measured using performance tests. Limited performance was coded in each test separately as follows: the inability or impaired performance in squatting and stair climbing (two steps up and down), a walking speed of <1.2 m/s when completing a 6.1 m course, the inability to rise from a chair without the help of the arms, and the inability to hold a semitandem position for 10 s (standing balance).25 Stair climbing, an ability essential for independent living in the society, was chosen as an indicator for mobility in the explanatory analyses. It correlated fairly well with other mobility indicators (r = 0.4–0.7). The contents of self‐reported and test‐based items were close enough enabling us to evaluate whether the contribution of the potential mediating factors to the educational differences is parallel across self‐reported and objectively measured mobility.

Potential mediating factors

Chronic conditions

Information on diseases was based on the clinical diagnoses made by the field doctors at the health examination. They applied uniform diagnostic criteria based on current clinical practice, according to written instructions. The following diseases were included: angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, intermittent claudication, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, asthma, knee and hip osteoarthritis, low‐back syndrome, chronic arthritis, injuries, neurological disease and dementia. Depressive and anxiety disorders during the past 12 months were determined by a mental health interview. Binocular visual acuity was measured from a distance of 4 m using a test chart, and classified as reduced if the score was <0.3.

Smoking and obesity

Smoking behaviour, inquired in the interview, was classified as non‐smokers, former smokers and current smokers. Body mass index (kg/m2) was based on weight and height measurements and classified into five categories: underweight (<20), normal (20–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), moderate obesity (30–34.9) and severe obesity (⩾35).

Work‐related physical loading

Information on lifetime exposure to (1) heavy physical work and (2) working in a kneeling or squatting position for at least 1 h per day was based on self‐reporting. A sum index for the years of exposure to these factors in the latest and five longest‐lasting jobs over a lifetime was created and classified into tertiles. The cut‐off values for tertiles were 1 and 30 years in women, and 5 and 45 years in men.

Statistical analyses

The analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software, which takes sampling design into account.26 The observations were weighted to reduce bias due to non‐response and to correct for oversampling of those aged ⩾80 years.27

Binary logistic regression analyses were used to describe educational differences separately in men and women. Model‐adjusted prevalences of mobility limitations by educational group were calculated using predicted marginals.27

Test‐based and self‐reported limitations in stair climbing were chosen as dependent variables in the explanatory analyses in the logistic regression models. The interaction between age and education was not significant in either outcome. The selection of the factors that were included in the explanatory analyses was based on three criteria: (1) they have been shown to be related to mobility disability, (2) they were associated with test‐based or self‐reported stair climbing (p<0.05), and (3) they were associated with education (p value for trend <0.1), in either women or men. The base model included age and education as independent variables. The effect of each factor on the educational differences in stair climbing was then examined individually. Finally, two additional models were fitted. In addition to age and education, the first one included smoking, body mass index and physical workload. The second model was further adjusted for chronic conditions. The ORs for low‐educational and intermediate‐educational groups obtained from these models were compared with the base model by calculating the relative decline of excess risk as follows: [(OR(base model )−OR(base model+intermediary factor(s)))/(OR(base model)‐1)]*100.28,29 Owing to missing values, 187 observations were excluded from the final models.

Results

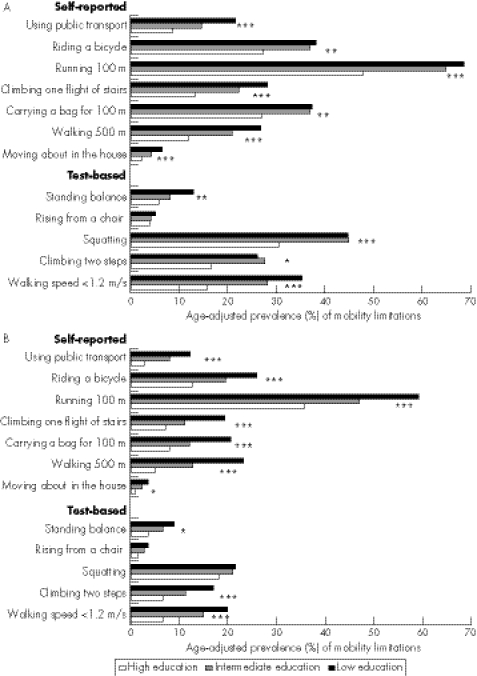

A clear gradient across the educational groups was observed in most of the self‐reported and test‐based indicators (fig 1). Among women, the ORs describing the relative difference between the lowest‐educational and the highest‐educational groups was 2.89 in self‐reported and 2.17 in test‐based stair‐climbing limitations; among men, the values were 3.30 and 3.53, respectively. Several chronic conditions and other factors were associated with these indicators, and their prevalence also varied by education (table 1).

Figure 1 Age‐adjusted prevalence (%) of mobility limitations by level of education in (A) women and (B) men. Statistical significance of the difference between the educational groups *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (Wald's test).

Table 1 Age‐adjusted ORs and 95% CI for difficulties in stair climbing by potential explanatory factors and their age‐adjusted* prevalence (%) by education.

| Difficulties in stair climbing | Level of education | p Value for trend† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test‐based | Self‐reported | High | Intermediate | Low | All | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | % | % | % | % | ||

| Women | |||||||

| Chronic conditions | |||||||

| Angina pectoris | 1.51 (1.05 to 2.17) | 3.00 (2.22 to 4.05) | 8 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 0.0299 |

| Heart failure | 2.07 (1.24 to 3.44) | 3.39 (1.92 to 5.98) | 3 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 0.0004 |

| Intermittent claudication | 3.00 (1.22 to 7.46) | 1.63 (0.70 to 3.81) | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.0549 |

| Diabetes | 2.87 (1.77 to 4.66) | 1.97 (1.30 to 3.00) | 6 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 0.2354 |

| Knee osteoarthritis | 3.51 (2.49 to 4.94) | 3.40 (2.46 to 4.70) | 11 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 0.0238 |

| Hip osteoarthritis | 2.24 (1.49 to 3.36) | 2.13 (1.45 to 3.13) | 6 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 0.0167 |

| Low‐back syndrome | 1.52 (1.04 to 2.22) | 1.65 (1.23 to 2.22) | 15 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 0.1453 |

| Dementia | 2.38 (0.97 to 5.83) | 1.84 (0.95 to 3.58) | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.0203 |

| Asthma | 1.76 (1.08 to 2.87) | 2.31 (1.50 to 3.56) | 7 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 0.0916 |

| Health behaviour | |||||||

| Smoking | 0.4684 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 1.00 | 1.00 | 80 | 80 | 77 | 79 | |

| Former smoker | 1.19 (0.78 to 1.81) | 1.87 (1.26 to 2.77) | 13 | 12 | 13 | 12 | |

| Current smoker | 1.24 (0.64 to 2.38) | 1.92 (1.17 to 3.16) | 7 | 8 | 10 | 9 | |

| Body mass index | <0.001 | ||||||

| <20 | 0.78 (0.32 to 1.90) | 0.55 (0.23 to 1.32) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| 20–24.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 38 | 25 | 19 | 26 | |

| 25–29.9 | 1.43 (0.98 to 2.09) | 1.21 (0.87 to 1.69) | 40 | 42 | 38 | 40 | |

| 30–34.9 | 3.31 (2.17 to 5.04) | 1.98 (1.37 to 2.84) | 17 | 23 | 28 | 23 | |

| ⩾35 | 7.09 (4.04 to 12.44) | 6.20 (3.75 to 10.26) | 2 | 9 | 12 | 9 | |

| Work conditions | |||||||

| Work‐related physical loading | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1st tertile ( = heaviest) | 1.37 (1.04 to 1.80) | 1.83 (1.35 to 2.47) | 12 | 36 | 43 | 34 | |

| 2nd tertile | 1.25 (0.86 to 1.82) | 1.32 (0.97 to 1.88) | 15 | 27 | 32 | 26 | |

| 3rd tertile | 1.00 | 1.00 | 73 | 37 | 24 | 40 | |

| Men | |||||||

| Chronic conditions | |||||||

| Angina pectoris | 1.00 (0.66 to 1.53) | 1.52 (0.94 to 2.46) | 13 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 0.0629 |

| Heart failure | 2.00 (0.96 to 4.21) | 3.62 (1.69 to 7.75) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0.6890 |

| Intermittent claudication | 1.10 (0.56 to 2.18) | 1.70 (0.80 to 3.62) | 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0.0389 |

| Diabetes | 3.09 (1.76 to 5.42) | 4.77 (3.05 to 7.46) | 4 | 9 | 12 | 9 | 0.0046 |

| Knee osteoarthritis | 3.96 (2.34 to 6.70) | 2.32 (1.35 to 3.98) | 8 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 0.0211 |

| Hip osteoarthritis | 1.69 (1.04 to 2.74) | 1.99 (1.16 to 3.41) | 8 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 0.0923 |

| Low‐back syndrome | 0.93 (0.57 to 1.52) | 1.94 (1.27 to 2.95) | 12 | 16 | 19 | 16 | 0.0423 |

| Dementia | 7.11 (2.17 to 23.29) | 6.62 (2.22 to 19.79) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.2432 |

| Asthma | 1.32 (0.67 to 2.59) | 2.12 (1.04 to 4.33) | 8 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 0.9625 |

| Health behaviour | |||||||

| Smoking | 0.0006 | ||||||

| Never smoker | 1.00 | 1.00 | 43 | 34 | 27 | 34 | |

| Former smoker | 1.43 (0.89 to 2.31) | 1.52 (0.95 to 2.43) | 41 | 47 | 50 | 47 | |

| Current smoker | 2.77 (1.61 to 4.74) | 3.67(2.20 to 6.10) | 16 | 19 | 23 | 19 | |

| Body mass index | 0.0017 | ||||||

| <20 | 4.41 (1.29 to 15.09) | 3.22(1.12 to 9.25) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20–24.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 27 | |

| 25–29.9 | 0.69 (0.44 to 1.06) | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.25) | 54 | 48 | 41 | 47 | |

| 30–34.9 | 1.22 (0.69 to 2.17) | 1.48(0.88 to 2.49) | 16 | 12 | 26 | 21 | |

| ⩾35 | 1.47 (0.44 to 4.93) | 6.76(2.99 to 15.26) | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 | |

| Work conditions | |||||||

| Work‐related physical loading | <0.001 | ||||||

| 1st tertile ( = heaviest) | 1.34 (0.80 to 2.23) | 1.91 (1.17 to 3.11) | 6 | 30 | 52 | 32 | |

| 2nd tertile | 1.56 (0.88 to 2.74) | 2.35 (1.47 to 3.75) | 17 | 40 | 37 | 34 | |

| 3rd tertile | 1.00 | 1.00 | 77 | 30 | 11 | 34 | |

*Age‐adjustment was performed separately for women and men.

†Trend was tested modelling the level of education as a continuous variable (1, low; 2, intermediate; 3, high).

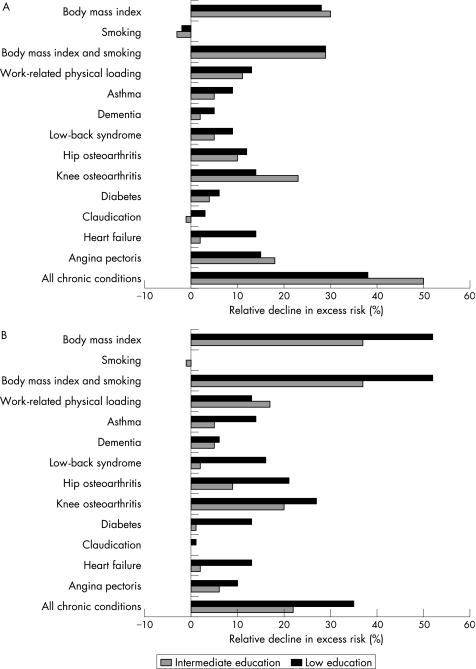

Among women, adjusting for obesity, work‐related physical loading, knee and hip osteoarthritis and cardiovascular diseases most strongly reduced the educational differences in self‐reported stair climbing (fig 2A). Adjusting for all chronic conditions produced a reduction of 38% between the lowest and highest educated groups. Health behaviours explained a third of the differences, but this was due to body mass index only, as smoking had no effect. Figure 2B gives a rather similar picture according to test‐based limitations; the effects of obesity and osteoarthritis were even greater, while cardiovascular diseases contributed less. In women, simultaneous adjustment for behavioural and work‐related factors lowered the excess risk of the test‐based or self‐reported mobility limitations of lower‐educational groups in contrast with the high‐educational group by 46–61%, depending on the group and the measure (table 2, model 1). When the chronic conditions were also adjusted for, the educational differences in the test‐based limitations vanished, but, despite a major reduction (72% and 61% in the intermediate‐educational and the low‐educational groups, respectively), the differences remained statistically significant in self‐reported difficulties (table 2, model 2).

Figure 2 Contribution of intermediary factors to educational differences in stair climbing in women (relative decline in excess risk*, %). (A) Self‐reported difficulties and (B) test‐based limitations. *[(OR(base model)−OR(base model+intermediary.factor(s)))/(OR(base model)‐1)]*100.

Table 2 Educational differences in stair climbing, sequentially adjusted for intermediary factors.

| Model 0* | Model 1† | Decline‡ | Model 2§ | Decline‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | |||||

| Test‐based limitations | |||||

| High education | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate education | 2.41 (1.49 to 3.90) | 1.73 (1.02 to 2.92) | 49 | 1.45 (0.84 to 2.50) | 68 |

| Low education | 2.17 (1.33 to 3.54) | 1.46 (0.82 to 2.58) | 61 | 1.21 (0.67 to 2.17) | 82 |

| Self‐reported difficulties | |||||

| High education | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate education | 2.03 (1.30 to 3.17) | 1.55 (0.96 to 2.52) | 47 | 1.29 (0.76 to 2.17) | 72 |

| Low education | 2.89 (1.89 to 4.42) | 2.03 (1.26 to 3.25) | 46 | 1.73 (1.05 to 2.85) | 61 |

| Men | |||||

| Test‐based limitations | |||||

| High education | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate education | 1.97 (0.97 to 4.01) | 1.94 (0.90 to 4.16) | 4 | 1.83 (0.77 to 4.37) | 15 |

| Low education | 3.53 (1.74 to 7.15) | 3.05 (1.38 to 6.75) | 19 | 2.26 (0.94 to 5.46) | 50 |

| Self‐reported difficulties | |||||

| High education | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Intermediate education | 1.66 (0.93 to 2.95) | 1.20 (0.62 to 2.35) | 69 | 1.06 (0.51 to 2.23) | 90 |

| Low education | 3.30 (1.81 to 6.03) | 2.02 (1.00 to 4.07) | 56 | 1.57 (0.72 to 3.45) | 75 |

Values are ORs with 95% CIs and decline in excess risk (%).

*Model 0: age‐adjusted.

†Model 1: model 0 + smoking, body mass index + work‐related physical loading.

‡Relative decline was calculated: [(OR(model0)‐OR(model0+intermediary factors))/(OR(model0)‐1)]*100.

§Model 2: model 1 + chronic conditions (angina pectoris, heart failure, intermittent claudication, diabetes, knee and hip osteoarthritis, low‐back syndrome, dementia and asthma).

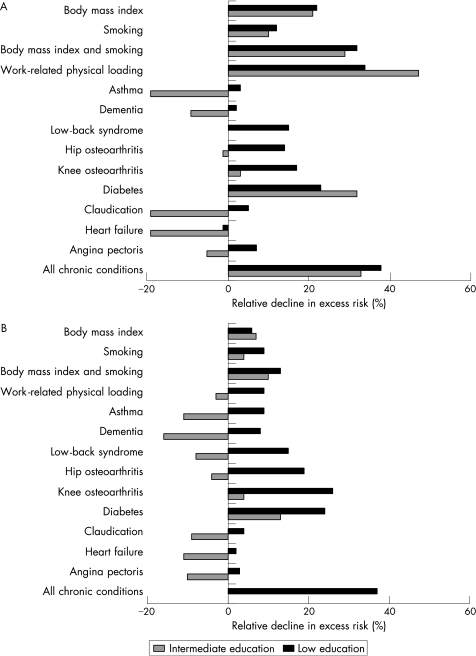

In men, work‐related physical loading, health behaviours, diabetes and musculoskeletal diseases substantially reduced the risk of self‐reported disability of the lowest‐educated group compared with the highest‐educated group (fig 3A). The effects on the excess risk of the intermediate‐educational group were inconsistent, with some factors decreasing and others increasing mobility limitation risks. The contribution of work‐related physical loading and obesity were considerably weaker in the test‐based performance (fig 3B). More than half (56–69%) of the differences in self‐reported difficulties among men were explained by controlling for behavioural and work‐related factors simultaneously (table 2). A further reduction occurred when chronic conditions were also taken into account. The sequential adjustment of the mediating factors reduced the educational differences less in test‐based than in self‐reported limitations. However, the differences lost statistical significance in the final model.

Figure 3 Contribution of intermediary factors to educational differences in stair climbing in men (relative decline in excess risk*, %). (A) Self‐reported difficulties and (B) test‐based limitations. *[(OR(base model)−OR(base model+intermediary.factor(s)))/(OR(base model)‐1)]*100.

Discussion

The findings from this nationally representative sample of elderly Finnish adults add new evidence to the existing literature about social position and functioning by extending the scope from self‐reporting to objectively measured mobility, and furthermore, by assessing the mechanisms through which low education translates to poorer functioning. We found large differences in mobility between educational groups. Furthermore, the excess risk of mobility limitations of those with lower education, compared with the highest educated, was largely due to the higher prevalence of obesity, chronic conditions and history of physically strenuous work in the lower‐educational groups.

Educational differences in mobility

A similar pattern of educational differences was present in a wide array of self‐reported and test‐based mobility measures. In addition to the generally used indicators of walking and stair climbing, the least educated performed worse than their more‐educated peers in tasks requiring strength (squatting, carrying a bag), balance (bicycling, tandem stand) and aerobic capacity (running). Our results are in congruence with the previous findings on elderly populations from different countries.3,4,5,6,7,20,30

Effect of smoking and obesity

A large proportion of the educational differences in mobility was mediated through smoking and obesity. Obesity had a great impact on disparities in women in particular, while smoking reduced the differences in men. There are two obvious reasons for the gender difference: firstly, the strength of the association of mobility with obesity and smoking varied for men and women, and secondly, the educational distribution of the factors was different between the genders. Obesity affected mobility more seriously in women; also the educational differences in body mass index were more pronounced than in men. In all educational groups, few elderly women smoked, whereas there was a clear gradient for men: less‐educated men smoked more frequently than their better‐off counterparts.

Several studies have focused on the role of health behaviours and obesity on socioeconomic inequalities in functioning,14,15,16,18,19 but most of them fail to show the gender‐specific effect of individual behaviours. The degree to which obesity and smoking contributed to the disparities in our data corresponds with the results of Lantz et al,16 who investigated the effect of smoking, alcohol consumption, overweight and physical inactivity on socioeconomic inequalities in self‐assessed physical functioning over a 7.5‐year period. After simultaneous adjustment for behaviours, the OR for the walking and stair‐climbing problems of the least‐educated group compared with the highest‐educated group fell from 2.96 to 2.21, corresponding to a 38% decline in excess risk among the least educated. In contrast, Clark et al19 observed no effect of health behaviours on the association of education and onset of limitations in walking and stair climbing over a 2‐year follow‐up.

Effect of physical workload

Our study adds to the existing body of knowledge by showing that a substantial part of the educational gradient in mobility limitations is attributable to the history of workload, which is a challenge to the occupational healthcare. Our finding is in line with prior studies showing the contribution of ergonomic and physical working conditions on self‐reported health11,31,32 and functioning.17 Heavy physical loading is an important risk factor for osteoarthritis, and thereby causes mobility restrictions.33 In addition, physically demanding work may be connected with adverse behaviours, such as smoking, unhealthy dietary habits and obesity, which are more common in lower‐occupational groups.11,32 This indirect effect was also seen in our analyses: workload lost most of its explanatory power when health behaviours were controlled for. The strength of our finding is that the history of physically strenuous work covered practically the entire working life—that is, the last (or current) and five longest‐lasting jobs. It can be assumed that the effects of the exposure on mobility accumulate over time, and therefore lifetime exposure explains the educational differences better than the current situation.34 The use of lifetime exposure to work factors enabled us to analyse the whole sample and not just those who were currently working, thus avoiding the “healthy worker” bias.

Effect of chronic conditions

Mobility limitations among the elderly are often caused by chronic conditions, with multiple environmental and personal factors influencing and modifying this dynamic disablement process.2,35 Almost 40% of the educational differences in mobility limitations were explained by chronic conditions. Our results parallel those observed by Graciani et al.5 However, others have reported a negligible effect of chronic conditions on the socioeconomic disparities in self‐reported walking and stair‐climbing ability.19,21 The inconsistency concerning the effect of chronic conditions may stem from several sources—for example, the comprehensiveness and severity of diseases considered, the reliability of their measurement and the approach used to adjust the diseases in the multivariate models.

Two recent studies have focused on the effect that a specific disease has on the educational differences in mobility. Koster et al14 found that self‐reported knee pain was among the factors contributing most to the differences in walking and stair climbing. Nusselder et al36 reported that arthritis, low‐back complaints (in men) and heart disease/stroke contributed to the differences in mobility‐related disability‐free life expectancy. The results of these studies and the present findings accentuate the importance of prevention and effective treatment of musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases to reduce the socioeconomic differences in mobility.

Methodological considerations

This study was based on a representative sample of the elderly Finnish population with a high level of participation. The analyses were limited to those who had both health interview and examination data. Even though the persons who did not attend the proper health examination were more disabled than those who participated,25 no indication of results biased by this non‐participation was noted, as the association between education and mobility was similar among those who only had the health interview compared with those who also had the examination (data not shown).

The cross‐sectional design of the study restricts causal inferences. The temporal order of education, intermediary factors and mobility limitations cannot be determined. However, reversed causation is assumed to be minimal since education is generally acquired in early adulthood. More problematic is the temporal order of the intermediary factors and mobility limitations, as functional limitations may induce new health problems.35

The mechanisms through which education is connected with mobility are complicated. Although we were able to cover many of the potential mediating factors, other factors could also be relevant. Physical activity protects against the decline in functional ability,9,37 but because of its close and reciprocal associations with mobility it was not included in the analyses. The same also applies to alcohol use: only women who did not drink had an increased risk of mobility limitations. It is plausible that women who do not drink have stopped drinking because of disabling medical reasons. Compared with total abstaining, moderate alcohol consumption may also be related to a decreased risk of having disabling cardiovascular events.37

In this study, information on diseases was confirmed by a doctor in a comprehensive health examination, as opposed to self‐reported data in prior studies. More valid verification of the chronic conditions may therefore have revealed their effect better. The accuracy of self‐reported musculoskeletal diseases has been found to be quite poor, whereas cardiovascular diseases are distinguished more reliably on the basis of self‐report.38,39 Educational differences in misreporting may bias the prevalence of morbidity,23,38 thus also modifying its effect on inequalities. Guralnik et al8 have pointed out that different diseases have task‐specific impacts on functioning. Because we analysed a specific task (stair climbing) and separate diseases, the impact of diseases on educational differences are probably greater than in studies using a summary measure of disability and a simple count measure of diseases.9 Finally, the functional capacity of the participants and their diagnoses were determined independently of each other. This further supports the validity of our findings, as the over‐reporting of diseases has been found among those with self‐reported mobility limitations.39

What is already known

The prevalence of mobility limitations is higher among persons with lower socioeconomic status compared with persons with a higher status.

What this paper adds

An educational gradient was found in a comprehensive set of self‐reported and test‐based mobility indicators. Specific factors contributing to the educational differences in mobility were identified: in women a substantial part of the educational gradient was attributable to obesity, history of physically strenuous work, and musculoskeletal and cardiovascular diseases, while in men diabetes and smoking also had an important effect.

Policy implications

Information on the identified factors that contribute to the educational differences in mobility can be used in health and social policy when planning targeted interventions. General health promotion, using methods that yield good results in the lowest‐educational groups, is a good strategy to reduce the disparities in mobility.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated large educational inequalities in various measures of self‐reported and test‐based mobility. Common chronic diseases, obesity, smoking and workload appeared to be the main pathways from low education to mobility limitations. General health promotion, using methods that also yield good results in the lowest‐educational groups, is thus a good strategy to reduce the disparities in mobility.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Health 2000 participants and field personnel, and Tommi Härkänen, PhD for valuable advice concerning the statistical methods.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was financially supported by the Academy of Finland (grant 205631) and by the Research Programme of KTL on Health Inequalities.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Guralnik J M, Ferrucci L, Simonsick E M.et al Lower‐extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995332556–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001

- 3.Ahacic K, Parker M G, Thorslund M. Mobility limitations in the Swedish population from 1968 to 1992: age, gender and social class differences. Aging (Milano) 200012190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulander T T, Rahkonen O J, Uutela A K. Functional ability in the elderly Finnish population: time period differences and associations, 1985–99. Scand J Public Health 200331100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graciani A, Banegas J R, Lopez‐Garcia E.et al Prevalence of disability and associated social and health‐related factors among the elderly in Spain: a population‐based study. Maturitas 200448381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melzer D, Parahyba M I. Socio‐demographic correlates of mobility disability in older Brazilians: results of the first national survey. Age Ageing 200433253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huisman M, Kunst A, Deeg D.et al Educational inequalities in the prevalence and incidence of disability in Italy and the Netherlands were observed. J Clin Epidemiol 2005581058–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guralnik J M, Fried L P, Salive M E. Disability as a public health outcome in the aging population. Annu Rev Public Health 19961725–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuck A E, Walthert J M, Nikolaus T.et al Risk factors for functional status decline in community‐living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 199948445–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holte H H, Tambs K, Bjerkedal T. Manual work as predictor for disability pensioning with osteoarthritis among the employed in Norway 1971–1990. Int J Epidemiol 200029487–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundberg O. Causal explanations for class inequality in health—an empirical analysis. Soc Sci Med 199132385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalstra J A, Kunst A E, Borrell C.et al Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int J Epidemiol 200534316–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laaksonen M, Prattala R, Helasoja V.et al Income and health behaviours. Evidence from monitoring surveys among Finnish adults. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koster A, Penninx B W, Bosma H.et al Is there a biomedical explanation for socioeconomic differences in incident mobility limitation? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005601022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martikainen P, Stansfeld S, Hemingway H.et al Determinants of socioeconomic differences in change in physical and mental functioning. Soc Sci Med 199949499–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lantz P M, Lynch J W, House J S.et al Socioeconomic disparities in health change in a longitudinal study of US adults: the role of health‐risk behaviors. Soc Sci Med 20015329–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamson J, Hunt K, Ebrahim S. Socioeconomic position, occupational exposures, and gender: the relation with locomotor disability in early old age. J Epidemiol Community Health 200357453–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross C E, Wu C. The links between education and health. Am Sociol Rev 199560719–745. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark D O, Stump T E, Wolinsky F D. Predictors of onset of and recovery from mobility difficulty among adults aged 51–61 years. Am J Epidemiol 199814863–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rautio N, Heikkinen E, Heikkinen R L. The association of socio‐economic factors with physical and mental capacity in elderly men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 200133163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avlund K, Damsgaard M T, Osler M. Social position and functional decline among non‐disabled old men and women. Eur J Public Health 200414212–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beland F, Zunzunegui M V. Predictors of functional status in older people living at home. Age Ageing 199928153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackenbach J P, Looman C W, van der Meer J B. Differences in the misreporting of chronic conditions, by level of education: the effect on inequalities in prevalence rates. Am J Public Health 199686706–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aromaa A, Koskinen S. eds. Health and functional capacity in Finland. Baseline results of the Health 2000 health examination survey. Helsinki: Hakapaino, 2004. http://www.ktl.fi/health2000/index.uk.html (accessed 30 January 2007)

- 25.Sainio P, Koskinen S, Heliövaara M.et al Self‐reported and test‐based mobility limitations in a representative sample of Finns aged 30+. Scand J Public Health 200634378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Research Triangle Institute SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 8.0. Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC 2001

- 27.Korn E L, Graubard B I.Analysis of health surveys. New York: Wiley, 1999

- 28.van Oort F V, van Lenthe F J, Mackenbach J P. Material, psychosocial, and behavioural factors in the explanation of educational inequalities in mortality in the Netherlands. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laaksonen M, Roos E, Rahkonen O.et al Influence of material and behavioural factors on occupational class differences in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559163–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guralnik J M, LaCroix A Z, Abbott R D.et al Maintaining mobility in late life. I. Demographic characteristics and chronic conditions. Am J Epidemiol 1993137845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrijvers C T, van de Mheen H D, Stronks K.et al Socioeconomic inequalities in health in the working population: the contribution of working conditions. Int J Epidemiol 1998271011–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borg V, Kristensen T S. Social class and self‐rated health: can the gradient be explained by differences in life style or work environment? Soc Sci Med 2000511019–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felson D T, Lawrence R C, Dieppe P A.et al Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med 2000133635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monden C W. Current and lifetime exposure to working conditions. Do they explain educational differences in subjective health? Soc Sci Med 2005602465–2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verbrugge L M, Jette A M. The disablement process. Soc Sci Med 1994381–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nusselder W J, Looman C W, Mackenbach J P.et al The contribution of specific diseases to educational disparities in disability‐free life expectancy. Am J Public Health 2005952035–2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaCroix A Z, Guralnik J M, Berkman L F.et al Maintaining mobility in late life. II. Smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and body mass index. Am J Epidemiol 1993137858–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heliovaara M, Aromaa A, Klaukka T.et al Reliability and validity of interview data on chronic diseases. The Mini‐Finland Health Survey. J Clin Epidemiol 199346181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kriegsman D M, Penninx B W, van Eijk J T.et al Self‐reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients' self‐reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol 1996491407–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]