Abstract

Low folate has been causatively linked to depression, but research is contradictory. An association may arise due to chance, bias, confounding or reverse causality. A systematic review of observational studies which examined the association between depression and folate was conducted. 11 relevant studies (15 315 participants; three case–control studies, seven population surveys and one cohort study) examining the risk of depression in the presence of low folate were found. Pooling showed a significant relationship between folate status and depression (odds ratio (OR)pooled unadjusted = 1.55; 95% CI 1.26 to 1.91). This relationship remained after adjustment for potential confounding (OR)pooled adjusted = 1.42; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.83). Folate levels were also lower in depression. There is accumulating evidence that low folate status is associated with depression. Much of this evidence comes from case–control and cross‐sectional studies. Cohort studies and definitive randomised‐controlled trials to test the therapeutic benefit of folate are required to confirm or refute a causal relationship.

Depression will soon become the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1 It affects between 5% and 10% of individuals, and is the third most common reason for consultation in primary care.2 Since the advent of accurate assay techniques in the 1960s, a link between folate deficiency and depression has been postulated. The evidence linking low folate status and depression seems to come from two complementary sources of evidence. First, a significant percentage of patients with depression are reported to have low folate levels.3,4 Second, some studies have shown that folate can be used to augment conventional treatments for depression and to improve the outcome.5

Folate is intimately linked to methylation processes and the synthesis of neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, such as serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine; 5‐HT). The 1‐carbon cycle/folate metabolic pathway is complex; and it regulates nucleotide synthesis and also DNA methylation. 5‐Methyltetrahydrofolate is the predominant circulating form of folate, which donates a methyl group to homocysteine during the generation of S‐adenosylmethionine, a major source of methyl groups in the brain.6 Several of the key enzymes in the 1‐carbon cycle are folate‐dependant in their activity, and this forms a biologically plausible link between folate and mood.7

Folate (in the form of folic acid) is a cheap and relatively safe food supplement with a number of proven health benefits.8 Food fortification is used in several countries (including the United States, Canada and Australia),9,10 and is being considered in others (including the UK).11 The demonstration of a population‐level benefit of folate in terms of mental health and well‐being might be informative to these debates.

The existence of a possible relationship between low folate status and depression has been examined in more detail using observational epidemiological designs, but with conflicting results. A core feature of depression is reduced appetite, and therefore impaired nutritional status.12 Depression is also commonly associated with alcohol excess, which is known to impair folate absorption and deplete stores of folate.13 Both of these factors could confound any relationship between folate, folate metabolism and depression.14 Different estimates of the relationship between folate status and depression might therefore emerge, depending on the degree to which confounding has been addressed in the design and analysis of studies.

Meta‐analyses are now being increasingly used to increase the precision and strength of association from observational studies15 and to examine sources of heterogeneity between studies,16 including the effects of bias and confounding on observed associations.17,18,19 For example, Pettiti20 applied meta‐analysis to examine the putative relationship between oestrogen replacement and coronary heart disease, and to explain why some studies showed an association whereas others did not. Similarly, Ford and colleagues21 have examined the relationship between homocysteine and cardiovascular disease using meta‐analysis.

We carried out a meta‐analysis in order to examine whether there is an association between low folate status and depression, and whether this relationship persists when important sources of bias and confounding were accounted for.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis in line with best practice guidelines on the synthesis of observational epidemiological data.19,22

Search strategy

We searched a broad range of medical, psychiatric and nutritional databases with no language restrictions. The following were searched from inception to November 2005: Medline; Embase; PsycINFO, BIOSIS, CAB Abstracts (for human nutrition) and Science Direct. Search terms were used to capture relevant studies, using exploded subject headings, synonyms and free text terms for folate, and depression, with a series of terms for depression‐related studies adapted from the Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis Group23—full search terms are available from the authors (see appendix 1 for an example). Reference lists of retrieved studies were also checked for further relevant studies. Search results were scrutinised and studies were selected independently by two reviewers.

Inclusion criteria

We sought all cross‐sectional, case–control and prospective and retrospective cohort epidemiological designs which examined the relationship between folate status and depression. To be included, studies must have drawn some comparison between the presence of low folate status and depression, and must have used some comparison or control group.

Data extraction

Wherever possible, exposure to low folate and depression status were each stratified as categorical variables. Summary odds ratios (ORs) and group mean folate levels, with attendant 95% CIs, were extracted or calculated from original data. Both unadjusted and adjusted summary ORs were sought, where authors had provided these. When these data were not available from publications, first authors were contacted for either calculated or raw data. Studies were selected and data were extracted independently by two reviewers, with reference to a third reviewer for areas of disagreement.

Statistical analysis

Summary ORs of low folate status were combined using a random effects meta‐analysis.24 Differences in mean folate levels between people who and were and were not depressed were pooled using a standardised effect size.17 We chose this method to allow both mean serum and red cell folate, measured with a variety of different assay techniques, to be combined across studies. Between‐study heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.25 The I2 statistic has several advantages over other measures of heterogeneity (such as χ2), including greater statistical power to detect clinical heterogeneity when fewer studies are available. As a guide, I2 values of 25% may be considered low, 50% moderate and 75% high.25

We sought to explore any potential causes of heterogeneity—particularly due to confounding, study design and method of folate assay. The relationship between low folate status and depression was explored in more detail by conducting a series of a priori sensitivity analyses to examine the degree to which any association between folate status and depression might be influenced by the design and analysis of primary studies. We hypothesised that confounding might result in an overestimation of the association between low folate and depression, and that studies which minimise or adjust for confounding using matching, restriction, adjustment, stratification or multivariate analysis might produce more conservative and realistic estimates of association. Specific evidence of adjustments for diet, nutritional status and alcohol consumption were sought. In addition, we looked for heterogeneity due to study design, where prospective cohort studies were likely to be the most reliable.

Studies were in the first instance pooled separately according to these variables, and, where possible, a statistical analysis was undertaken to test for a relationship between study level variables and ORs using logistic meta‐regression.26 p Values for meta‐regression were calculated using 1000 Monte‐Carlo simulations, with a permutation test to avoid potential false positives.27 The presence of publication bias was assessed using Egger's weighted regression test.28 All analyses were conducted using STATA V.8, using the metan, metareg and metabias series of commands.

Results

Our searches produced 2145 potentially relevant references, of which 19 met our inclusion criteria and provided usable data.

Low folate status as a risk factor for depression

In all, 11 of the 19 studies (15 315 participants) examined the relationship between low folate status and depression as categorical variables, and provided sufficient data to calculate ORs (table 1). Seven of these were cross‐sectional studies,29,30,31,32,33,34,35 whereby folate status and depression were ascertained simultaneously from population surveys and the proportion of patients with depression with low folate status was compared with that of patients without depressing with low folate status. Cross‐sectional studies were often drawn from large population‐based cohort studies examining the relationship between a whole series of physical and nutritional variables and health outcomes—for example, one large cross‐sectional study32 was drawn from the Women's Health and Ageing study.36 Within these population surveys, depression status was ascertained either by standardised interview or by scores on a standardised psychometric instrument, such as the Geriatric Depression Scale, in the case of the Women's Health and Ageing study.

Table 1 Observational studies examining the relationship between folate status and risk of depression.

| Study | Design | Population | Case definition | Controls | Definition of low folate | Confounders and adjustment | Unadjusted OR (>1 = association) | Adjusted OR (>1 = association) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abou‐Saleh and Coppen 39 | Case–control | Consecutive psychiatric inpatients and day‐hospital patients with depression | ICD‐9 major depression (n = 95) | Laboratory and hospital staff with no depression (n = 60) | Serum folate | None | OR 12.74 (95% CI 2.97 to 113.48) | NA |

| <2.5 ng/ml | ||||||||

| <5.67 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Carney et al37 | Case–control | Consecutive inpatient psychiatric admissions | Depression diagnosed by a psychiatrist (n = 152) | Euthymic controls (n = 42) | Red cell folate | None | OR 3.93 (95% CI 0.63 to 24.61) | NA |

| <150 ng/ml | ||||||||

| <337 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Lee et al38 | Case–control | Consecutive inpatient psychiatric admissions aged 15–87 years | DSM‐III‐R major depression (n = 117) | Hospital staff with no history of depression (n = 72) | Red cell folate | None | OR 0.77 (95% CI 0.24 to 2.57) | NA |

| <150 ng/ml | ||||||||

| <337.8 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Lindeman29 | Cross‐sectional survey | Hispanic males and females aged ⩾65 years | GDS score >6 (n = 74) | Not currently depressed and from the same population (n = 709) | Serum folate | None | OR 1.51(95% CI 0.82 to 2.71 ) | NA |

| <5 ng/ml | ||||||||

| <11.1 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Tiemeier et al31 | Cross‐sectional survey | Patients >55 years from a population survey | DSM‐IV depression or dysthymia (n = 112) | Randomly selected non‐depressed people from the same population (n = 416) | Serum folate | Age, gender, education, smoking, alcohol intake, cognitive functioning | OR 1.52 (95% CI 0.85 to 2.71) | OR 1.49 (95% CI 0.83 to 2.67) |

| <5.03 ng/ml <11.4 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Plus raised homocysteine (>13.9 nmol/L) | ||||||||

| Pennix et al32 | Cross‐sectional survey | Women ⩾65 years from a Population survey | Severe depression on the GDS score ⩾14 (n = 122) | Non‐depressed people from the same population, GDS score ⩽9 (n = 478) | Serum folate | Age, race education; income; BMI serum creatinine; CCF; diabetes; disability; cancer | OR 0.78 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.73) | OR 0.90 (95% CI 0.24 to 3.36) |

| <5.03 ng/ml | ||||||||

| <11.4 nmol/l | ||||||||

| and raised homocysteine (>13.9 nmol) | ||||||||

| Bjelland et al33 | Cross‐sectional survey | Men and women aged 46–49 and 70–74 years from a population cohort study | High score on HAD >8 (n = 243) | Non‐depressed people from the same population (n = 5705) | Serum folate | Age, sex, smoking status, educational level | OR 1.48 (95% CI 0.93 to 2.37) | OR 1.31 (95% CI 0.82 to 2.11) |

| <1.68 ng/ml | *Least adjusted–adjusts only for age and sex | |||||||

| <3.8 nmol/l | ||||||||

| Tolmunen et al30 | Cross‐sectional survey | Middle‐aged Finnish men 42–60 years from a population cohort | High score on HPL scale ⩾5 (n = 228) | Non‐depressed people from the same population (n = 2215) | Ascertained from dietary records. Lowest third tertile of folate intake (daily intake <201.9 (SD 52) μg/day | Age, sex, smoking, alcohol, appetite, BMI, living alone, education, SES, fat consumption | OR 1.67 (95% CI 1.19 to 2.35) | OR 1.46 (1.01 to 2.12) |

| *Least‐adjusted for age and examination years | ||||||||

| Tolmunen et al40 | Cohort study | Middle‐aged Finnish men 42–60 years from population cohort | Hospital discharge diagnosis of ICD major depression during 15‐year follow‐up (n = 47) | No ICD diagnosis of depression during 15‐year follow‐up (n = 2313) | Ascertained from dietary records. Below median folate intake (256 μg/day) | Age and examination year, SES, baseline depression score, daily intake of fibre, vitamin C and fat | OR 3.04 (95% CI 1.58 to 5.86) | OR 2.53 (95% CI 1.17 to 5.48) |

| *OR approximated directly from reported RR | *Cohort reports the same subjects as the above study,30 so prospective data rather than cross‐sectional data included in meta‐analysis only | |||||||

| Morris et al34 | Cross‐sectional study | Males and females aged 15–39 years from a US National Population Nutrition Survey | Lifetime risk of DSM‐III major depression (n = 301) and dysthymia (n = 121) ascertained by diagnostic interview (total n = 422) | Ethnically diverse members from the same population (n = 2526) | Red cell folate below 25th centile in the population* Cut‐off provided by author | Gender age, race, income, education, alcohol use, drug use, weight and nutritional status | OR 1.7 (95% CI 1.1 to 2.6) | OR 2.4 (95% CI 1.3 to 4.4) |

| <196 ng/ml | †Least adjusted–adjusts only for age, sex and ethnicity | |||||||

| <445 nmol/l | Based upon unpublished data from author. | |||||||

| Ramos et al35 | Cross‐sectional study | Elderly Latino males (n = 627) and females (n = 883) aged ⩾60 years | CES‐D score >15 (n = 385) | Depression score ⩽15 from the same population (n = 1125) | Serum folate in lowest tertile* | Age, education, B12 status, homocysteine levels, use of folate supplements, use of anti‐depressants and alcohol consumption | Overall OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.65) | Overall OR 75 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.33) |

| <11.2 ng/ml | Folate*sex interaction, so analysis also presented separately for men and women. | Folate*sex interaction, so analysis also presented separately for men and women. | ||||||

| <25.4 nmol/l | Men OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.56 to 1.65) | Men OR 0.74 (95% CI 0.40 to 1.35) | ||||||

| Study conducted post‐fortification | Women OR 2.08 (95% CI 1.47 to 2.95) | Women OR 2.04 (95% CI 1.38 to 3.02) |

BMI, body mass index; CCF, congestive cardiac failure; CES‐D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for mental disorders; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HAD, Hospital Anxiety and Depression; HPL, Human Population Laboratory; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NA, not applicable; SES, socioeconomic status.

Three studies were hospital‐based case–control studies,37,38,39 where successive patients with a diagnosis of clinical depression were selected from a clinical setting and their folate status was ascertained. The proportion of patients with low folate status was then compared with that in a control population.

Only one study40 was a prospective cohort study, which included 2313 middle‐aged (42–60 years) Finnish men. People with pre‐existing depression were excluded from the inception cohort and folate intake was ascertained from food diaries. Follow‐up was done over 15 years and depression outcomes were ascertained from hospital inpatient episodes with an International Classification of Diseases diagnosis of major depression.12

A variety of age ranges were included in the observational studies. Clinic‐ and hospital‐based studies drew a range of patients with depression aged between 15 and 87 years. Population‐based studies drew their samples from a range of sources, some of which were broad and representative of working‐age adults,34 and some of which were restricted to older adults31,35 or females.32 Depression status was ascertained either by diagnostic interview, according to standardised diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for mental disorders‐III,40 from clinician‐allocated diagnoses or by standardised interview schedules.

Studies ranged in sample size from 155 subjects39 to 5948 subjects,33 and population‐based cross‐sectional studies were much larger (median size 2443) than clinic/hospital‐based case–control studies (median size 155). Cross‐sectional and cohort studies were generally systematic in ensuring that sample participants were representative of the population being studied, and all provided data relating to depression and folate status on over 90% of participants. Case–control studies each claimed to recruit successive subjects with depression from the setting in which they were conducted, and controls were generally drawn from either non‐depressed hospital patients41 or from hospital staff.38

The influence of potential confounding variables was examined in all population‐based cross‐sectional surveys and cohort studies. For example, several studies measured nutritional status using body mass index and alcohol intake by self‐report (eg, Bjelland et al33 and Tolmunen et al40). Multivariate analyses of potentially confounding variables were used to produce both adjusted and unadjusted estimates in seven studies.30,31,32,33,34,35,40 Among case–control studies, no attempt was made to minimise potentially confounding factors by restriction, matching or adjustment.

Folate status and depression meta‐analysis:

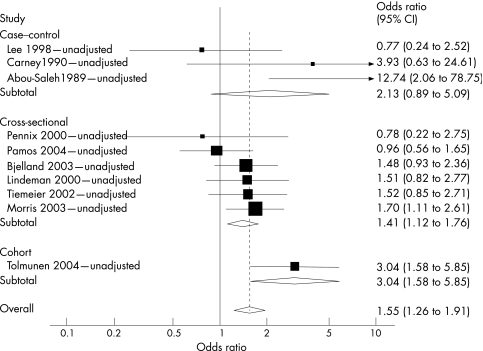

Sufficient data were available from all 11 studies to permit statistical pooling of the estimates of the relationship between categorical folate status and depression (fig 1). This meta‐analysis therefore included data from 15 315 participants—1769 with depression and 13 546 control subjects. Pooling of all estimates showed a significant relationship between folate status and depression (ORpooled unadjusted = 1.55; 95% CI 1.26 to 1.91), with a moderate level of between‐study statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 52%).

Figure 1 Meta‐analysis of depression and folate studies unadjusted for potential confounding, stratified by study design. Overall variation attributed to between‐study heterogeneity, I2 = 52%, with relative contributions by study design: case–control, I2 = 84%; cross‐sectional, I2 = 0%; and cohort, I2 not estimable.

Sensitivity analyses

Effect of study design

Among the overall group of studies, three case–control studies contributed a disproportionate degree of between‐study heterogeneity (I2 contribution = 83%). To examine the robustness of our overall result to the study design, we removed case–control studies and found that the magnitude of association was still significant, and that between‐study heterogeneity was considerably reduced to a low level (ORunadjusted = 1.52; 95% CI 1.17 to 1.97, I2 = 29%).

Adjustment for confounding

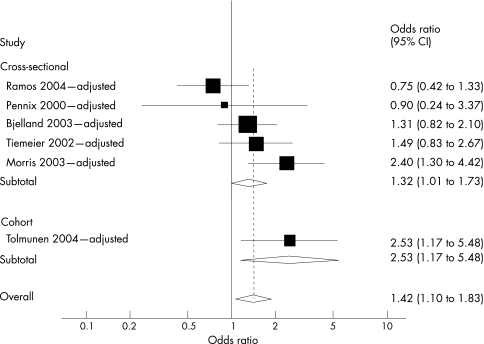

To examine the potential effect of confounding, we separately pooled only adjusted point estimates (fig 2). The pooled estimate of association was less pronounced, but remained significant (ORpooled adjusted = 1.42; 95% CI 1.10 to 1.83).

Figure 2 Meta‐analysis of depression and folate studies adjusted for potential confounding, stratified by study design. Overall variation attributed to between‐study heterogeneity, I2 = 51%, with relative contributions by study design: cross–sectional, I2 = 49%; cohort, I2 not estimable.

Method of folate assay

To examine the effect of folate ascertainment on the overall result, we first removed one study40 which established folate status using prospective dietary records rather than direct blood assay. This sensitivity analysis reduced the overall magnitude of association between low folate status and depression, but it remained statistically significant (ORpooled adjusted = 1.32; 95% CI 1.01 to 1.73; figure not shown). Among the remaining studies, two methods of biological folate ascertainment were used—serum and red cell folate. When we conducted a meta‐regression, with method of ascertainment as a predictive covariate, we found that the association between low folate status and depression was present irrespective of the method of assay used (logistic meta‐regression: association in studies using serum folate as assay method vs studies using plasma folate as assay method; β coefficient = 0.17, 95% CI –0.55 to 0.88, p = 0.60, I2 = 37%).

Folate fortification

On conducting a meta‐regression, with folate fortification as a predictive covariate, we found that the association between low folate status and depression was present irrespective of whether the population was subject to mandatory food fortification (logistic meta‐regression: association in studies where there was mandatory food fortification vs studies with no food statutory fortification (adjusted estimates only); β coefficient = 0.03, 95% CI –1.55 to 1.60, p = 0.96, I2 = 62%).

Publication bias

We also tested for the presence of publication bias using funnel plots and Egger's regression test28 and none was evident (zero intercept = unbiased; intercept = 0.05, 95% CI –2.60 to 2.71, p = 0.96; figure not shown).

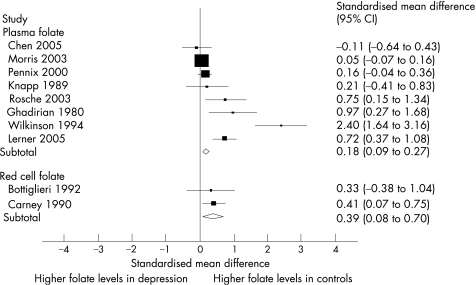

Between‐group differences in mean folate level

In all, 10 of the 19 studies (4600 subjects) provided sufficient data to allow between‐group comparisons of mean folate levels in populations with and without depression.14,32,34,37,41,42,43,44,45,46 Eight studies measured serum folate,32,34,41,42,43,44,45,46 and two estimated red cell folate.14,37 There was substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 84%; fig 3). Statistical pooling of these heterogeneous studies was not felt justified.

Figure 3 Meta‐analysis of standardised mean differences in folate levels between populations with or without depression. Overall variation attributed to between‐study heterogeneity, I2 = 84%.

Exploration of heterogeneity

Visual inspection of the Forrest plot (fig 3) showed that the overall trend among studies was for red cell and serum folate levels (both serum and red cell) to be lower in association with depression. When we undertook meta‐regression to explore the impact of our a priori sources of heterogeneity, we found no effect of study design (case–control vs cross‐sectional studies: β coefficient = –0.37, p = 0.50), method of assay (serum folate vs red cell folate: β coefficient = –0.21, p = 0.75) or adjustment for potential confounding (adjusted vs unadjusted: β coefficient = –0.55, p = 0.48).

Test for publication bias

Testing for publication bias showed borderline significant asymmetry, with larger studies showing a smaller degree of association than smaller studies (zero intercept = unbiased; intercept = 2.51, 95% CI 0.07 to 4.95, p = 0.05).

Discussion

This study represents, to our knowledge, the first meta‐analysis of nutritional studies of folate and depression. The main finding is that low folate status is associated with depression, although it is difficult to establish whether this relationship is causal. Several points are worthy of further discussion.

Limitations of the epidemiological evidence linking low folate to depression

The association between low folate status and depression seems to be robust, being based on a broad range of studies involving over 15 000 participants. This result is the same in studies accounting for potentially confounding variables such as age, nutritional status and co‐morbid alcohol disorders. However, the largest body of evidence for this review comes from epidemiologically weaker cross‐sectional and case–control studies that demonstrate only association, which may still be due to reverse causality. Some preliminary evidence of a direction of causality comes from the single‐cohort study40 in which folate was determined prior to the onset of depression, reducing the possibility of a reverse causal relationship.47,48 Clearly, this result needs replication in more than one study to begin to draw inference about the direction of causality between low folate and depression.

Heterogeneity is commonly found when conducting meta‐analysis, and the causes of heterogeneity should be examined in all cases.49 Our review provides further insight into the variable nature of the association between low folate status and depression which has been observed to date. Case–control studies are particularly susceptible to bias and confounding, and none of the available studies had addressed this. Removal of these studies substantially reduced the level of between‐study heterogeneity. Future case–control studies should account for confounding, and the results of reviews which do not examine heterogeneity, bias or confounding should be treated with some suspicion.19 Additionally, some potential sources of heterogeneity were not found to be influential. For example, an association between depression and low folate status was found in all countries, irrespective of whether there was a mandatory folate fortification programme. Similarly, an association was found irrespective of whether folate status was ascertained by dietary record, serum folate or red cell folate.

Is reduced folate causal? Complementary evidence from gene‐association studies

The results of the present review should be considered alongside emerging evidence of an association between impairments in folate metabolism and depression.50,51 The evidence of folate being a causal factor in depression is strengthened by an emerging association between the common polymorphism of a gene involved in the metabolism of folate—methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), and depression.13 The specific polymorphism MTHFR C677T has been found to be associated with depression in several studies,33,42,52,53,54 and has now been confirmed using meta‐analysis.50,51 The MTHFR C677T polymorphism mimics low folate status, but is not susceptible to either confounding or reverse causality. The association between depression and being homozygous for the MTHFR C677T polymorphism in genetic studies is of a similar magnitude (OR = 1.36) to that demonstrated in our least confounded pooled estimate in the present study. This is an example of what has been termed Mendelian randomisation and provides further circumstantial and complementary evidence of a potentially causal link between low folate status and depression.55,56

What this paper adds

Folate has been causatively linked to depression and a case has been made for folate in the prevention and treatment of depression at the population and individual levels.

This paper reviews the existing observational epidemiological literature and finds an association between low folate and depression.

This association remains the same even after adjustment for important confounding variables.

The association is largely based on large cross‐sectional studies and is confirmed in only one prospective cohort study. The possibility of reverse causality cannot be excluded.

Policy implications

Folate is a cheap and relatively safe food additive, and recent proposals to fortify food at a population level are given additional circumstantial support.

Further prospective research is needed to confirm or refute the causative role and therapeutic benefit of folate in preventing or treating depression.

Evidence of therapeutic benefit from folic acid supplementation

The results of this review should be considered alongside preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of folic acid in treating depression, or as an adjunct to antidepressant drugs. A recent Cochrane review57 has summarised these data and found three small trials involving 247 patients, but the trials were subject to several limitations. However, these have shown some benefit in using folic acid supplements either alone or in combination with antidepressants. Non‐randomised subgroup analyses have suggested that the greatest antidepressant effect is seen in those patients with the highest increase in folate levels (eg, Coppen and Bailey58). Clearly, further randomised trials are required to evaluate the role of folic acid in preventing and treating depression. In the absence of definitive randomised data, our current systematic review provides a summary of the best available observational evidence in this area. Whether this association and any therapeutic potential benefit for folic acid is confirmed in definitive randomised trials will be an important test of the validity of associations drawn from observational epidemiological and genetic designs.

Folic acid is a cheap and commonly used food supplement,8 and the identification of low folate status as a plausible specific risk factor for depression raises the possibility of using folic acid supplementation or improved diet in the prevention and treatment of depression at the population level.13 In the interim, the present review adds to the accumulating literature on the potential population benefits of mandatory fortification and of folic acid as a food supplement.

Abbreviations

MTHFR - methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase

Appendix 1

EXAMPLE OF MEDLINE SEARCH TERMS

((“folic acid”[MeSH Terms] OR folic acid[Text Word]) OR folate[All Fields] OR ((“vitamins”[TIAB] NOT Medline[SB]) OR “vitamins”[MeSH Terms] OR “vitamins”[Pharmacological Action] OR vitamin[Text Word]) OR (“methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (nadph2)”[MeSH Terms] OR MTHFR[Text Word])) OR ((“pharmaceutic adjuvants”[Text Word] OR “adjuvants, pharmaceutic”[MeSH Terms] OR “adjuvants, pharmaceutic”[Pharmacological Action]) AND ((“acids”[TIAB] NOT Medline[SB]) OR “acids”[MeSH Terms] OR acid[Text Word])) AND ((“depressive disorder”[TIAB] NOT Medline[SB]) OR “depressive disorder”[MeSH Terms] OR “depression”[MeSH Terms] OR depression[Text Word] OR depress$[text word] OR dysthym$[text word] OR “adjustment disorders”[MeSH Terms] OR adjustment disorder[Text Word])

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Each of the authors has contributed to the conception, design, conduct and analysis of this study and to the writing of this paper. SG acted as lead reviewer and is the guarantor of this paper.

References

- 1.Murray C J, Lopez A D.The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from disease, injuries and risk factors in 1990. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Bank, 1996

- 2.Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O'Brien M.et alOffice of National Statistics: psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households. 2000. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Carney M W P. Serum folate values in 423 psychiatric patients. BMJ 19674512–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds E H, Preece J M, Bailey J.et al Folate deficiency in depressive illness. Br J Psychiatry 1970117287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor M J, Carney S, Geddes J.et al Folate for depressive disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003(2)CD003390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Cantoni G L. S‐anenysylmethionine: a new intermediate formed enzymatically from 1‐methionine and adenosine triphosphate. J Biol Chem 1953204403–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds E H, Carney M W P. Methylation and mood. Lancet 198428196–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucock M. Is folic acid the ultimate functional food component for disease prevention? BMJ 2004328211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacques P F, Selhub J, Bostom A G.et al The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med 19993401449–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickling S, Hung J, Knuiman M.et al Impact of voluntary folate fortification on plasma homocysteine and serum folate in Australia from 1995 to 2001: a population based cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health 200559371–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Short R. UK government consults public on compulsory folate fortification. BMJ 2006332873a [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems ‐ 10th Revision. Geneva: WHO, 1990

- 13.Coppen A, Bolander‐Gouaille C. Treatment of depression: time to consider folic acid and vitamin B12. Jl Psychopharmacol 20051959–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottiglieri T. Homocysteine and folate metabolism in depression. Prog Neuro‐Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005291103–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petitti D B.Meta analysis, decision analysis and cost effectiveness analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

- 16.Berlin J A. Invited commentary. Am J Epidemiol 1995142383–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton A J, Abrams K R, Jones D R.et al Systematic reviews of trials and other studies. Health Technol Assess 199921–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M. Systematic reviews of observational studies. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews in health care. London: BMJ Books, 2000211–227.

- 19.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C.et al Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group. J Am Med Assoc 20002832008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettiti D B. Coronary heart disease and estrogen replacement therapy. Can compliance bias explain the results of observational studies? Ann Epidemiol 19944115–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford E S, Smith S J, Stroup D F.et al Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review of the evidence with special emphasis on case‐control studies and nested case‐control studies. Int Jo Epidemiol 20023159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD report 4. 2nd edn. York: University of York, 2001

- 23.Churchill R, Hunot V, McGuire H. Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis Group. In: Cochrane Library.I ssue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 2004

- 24.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 19867177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins J P, Thompson S G, Deeks J J.et al Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003327557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson S G, Sharp S J. Explaining heterogeneity in meta‐analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med 1999182693–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins J P T, Thompson S G. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta‐regression. Stat Med 2004231663–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey‐Smith G, Schneider M.et al Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997315629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindeman R D, Romero L J, Koehler K M.et al Serum vitamin B12, C and folate concentrations in the New Mexico Elder Health Survey: correlations with cognitive and affective functions. J Am Coll Nutr 20001968–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolmunen T, Voutilainen S, Hintikka J.et al Dietary folate and depressive symptoms are associated in middle‐aged Finnish men. J Nutr 20031333233–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiemeier H, van Tuijl H R, Hofman A.et al Vitamin B12, folate, and homocysteine in depression: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Psychiatry 20021592099–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Penninx B W, Guralnik J M, Ferrucci L.et al Vitamin B(12) deficiency and depression in physically disabled older women: epidemiologic evidence from the Women's Health and Aging Study. Am J Psychiatry 2000157715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjelland I, Tell G S, Vollset S E.et al Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and the MTHFR 677C‐>T polymorphism in anxiety and depression: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 200360618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris M S, Fava M, Jacques P F.et al Depression and folate status in the US Population. Psychother Psychosom 20037280–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos M I, Allen L H, Haan M N.et al Plasma folate concentrations are associated with depressive symptoms in elderly Latina women despite folic acid fortification. Am J Clin Nutr 2004801024–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasper J D, Shapiro S, Guralnik J M.et al Designing a community study of moderately to severely disabled older women: the Women's Health and Ageing Study. Ann Epidemiol 19999498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carney M W, Chary T K, Laundy M.et al Red cell folate concentrations in psychiatric patients. J Affect Disord 199019207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S, Wing Y K, Fong S. A controlled study of folate levels in Chinese inpatients with major depression in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord 19984973–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abou‐Saleh M T, Coppen A. Serum and red blood cell folate in depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand 19898078–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tolmunen T, Hintikka J, Ruusunen A.et al Dietary folate and the risk of depression in Finnish middle‐aged men. A prospective follow‐up study. PsychotherPsychosom 200473334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40a.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual–4th edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

- 41.Ghadirian A M, Ananth J, Engelsmann F. Folic acid deficiency and depression. Psychosomatics 198021926–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C S, Tsai J C, Tsang H Y.et al Homocysteine levels, MTHFR C677T genotype, and MRI hyperintensities in late‐onset major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 200513869–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knapp S, Irwin M. Plasma levels of tetrahydrobiopterin and folate in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 198926156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosche J, Uhlmann C, Froscher W. Low serum folate levels as a risk factor for depressive mood in patients with chronic epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci 20031564–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson A M, Anderson D N, Abou‐Saleh M T.et al 5‐Methyltetrahydrofolate level in the serum of depressed subjects and its relationship to the outcome of ECT. J Affect Disord 199432163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lerner V, Kanevsky M, Dwolatzky T.et al Vitamin B(12) and folate serum levels in newly admitted psychiatric patients. Clin Nutr 20052560–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hill A B. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 196558295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rothman K, Greenland S. Causation and causal inference. In: Rothman K, Greenland S, eds. Modern epidemiology. New York: Lippincott‐Raven, 19987–29.

- 49.Thompson S. Why sources of heterogeneity in meta‐analysis should be invetsigated. In: Chalmers I, Altman DG, eds. Systematic reviews. London: BMJ, 1995

- 50.Lewis S J, Lawlor D A, Davey Smith G.et al The thermolabile variant of MTHFR is associated with depression in the British Women's Heart and Health Study and a meta‐analysis. Mol Psychiatry 200611352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gilbody S, Lewis S, Lighfoot T. MTHFR polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol 20071651–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly C B, McDonnell A P, Johnston T G.et al The MTHFR C677T polymorphism is associated with depressive episodes in patients from Northern Ireland. J Psychopharmacol 200418567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan E C, Chong S A, Lim L C.et al Genetic analysis of the thermolabile methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase variant in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Psychiatr Genet 200414227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Almeida O P, Flicker L, Lautenschlager N T.et al Contribution of the MTHFR gene to the causal pathway for depression, anxiety and cognitive impairment in later life. Neurobiol Aging 200526251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization': can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol 2003321–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. What can mendelian randomisation tell us about modifiable behavioural and environmental exposures? BMJ 20053301076–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor M J, Carney S, Geddes J.et al Folate for depressive disorders (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2004

- 58.Coppen A, Bailey J. Enhancement of the antidepressant action of fluoxetine by folic acid: a randomised, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord 200060121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]