Abstract

Rotaviruses are the major etiological agents of diarrhea in children less than 5 years of age. The commonest G types in humans are G1-4 and G9. G12 is a rare human rotavirus (HRV) strain first reported in the Philippines. In this study, 13 G12 strains obtained from a community-based cohort and a hospital-based surveillance system in 2005 were characterized by phylogenetic analysis of partial nucleotide sequences of VP7, VP6, and NSP4 genes. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of VP7 gene sequences showed that these southern Indian strains had the greatest homology with G12 strains recently reported from eastern India (97-99% identity both at the nucleotide level and deduced amino acid level) and less homology with the prototype G12 strain, L26 (89-90% identity at the nucleotide level and 90-94% at the deduced amino acid level). Phylogenetic analysis of the VP6 and the NSP4 genes revealed that the Vellore G12 strains belonged to VP6 subgroup II and NSP4 genotype B. The P types associated with these strains were P[6] and P[8]. A G12 type-specific primer was designed for inclusion in an established VP7 G-typing multiplex RT PCR, and tested against a panel of known G types and untyped samples and was found to detect G12 strains in the multiplex-PCR. Close homology of the South Indian G12 strains to those from Kolkata suggests that G12 HRV strains are emerging in India. Methods for characterization of rotaviruses in epidemiological studies need to be updated frequently, particularly in developing countries.

Keywords: rotavirus, genotyping, phylogenetic analysis, primer design

INTRODUCTION

Group A rotaviruses are the major etiological agents of diarrhea in children less than 5 years of age [Kapikian et al., 2001]. According to a recent estimate, each year rotavirus causes 611,000 deaths in children worldwide, with the majority occurring in the developing world [Parashar et al., 2006].

Rotaviruses belong to the family Reoviridae and are non-enveloped viruses that have a genome of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA contained within a triple-layered protein capsid. The structural proteins are organized in a core (VP1-3), an inner shell (VP6) and an outer shell (VP7) from which the spikes (VP4) protrude. Differences in the antigen-specific epitopes on the inner capsid protein, VP6, allow the classification of rotaviruses into groups (A-G). Group A rotaviruses are further differentiated into subgroups (SGI, SGII, SGI and II, and SG non-I and non-II) based on reactivities with subgroup—specific monoclonal antibodies [Estes, 1996]. VP6 sequences of SGI or SGII from animal or human rotaviruses (HRVs) segregate into “animal” or “human” lineages within each subgroup [Iturriza Gomara et al., 2002].

The outermost layer of rotaviruses is composed of two proteins VP7 and VP4, which form the basis for the current dual classification of group A rotaviruses into G and P types. At least 15 different G types and 26 different P types have been found in human and animal infections [Estes, 1996; Kapikian et al., 2001; Martella et al., 2006]. G1, G2, G3, G4, and G9 strains in association with the P[4] and P[8] types are reported to be the commonest human genotypes [Santos and Hoshino, 2005]. Rotavirus strains with other less common G or P types have been isolated in different countries. G8 and G10 strains have been reported from UK, Brazil, Africa, and India; G5 strains have been reported from South America; P[3] strains from US and Israel; P[9] strains from Japan, UK, and the US, and P[11] strains from India [Ramachandran et al., 1996; Cunliffe et al., 1999; Iturriza-Gomara et al., 1999; Unicomb et al., 1999; Iturriza Gomara et al., 2004].

The non-structural protein, NSP4, is a viral enterotoxin which has been found to cause age-dependent diarrhea in neonatal suckling mice [Ball et al., 1996]. Analysis of the gene encoding NSP4 of various animal and HRV strains has identified five genotypes (A-E) [Ciarlet et al., 2000; Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2003]. As seen with the VP6 gene, the strains cluster within genotypes according to their species of origin [Ciarlet et al., 2000]. Therefore, sequence analysis of the NSP4 gene in conjunction with the VP6 gene can be used to determine if an emerging strain is likely to be the result of zoonotic introduction.

G12 HRV strains were first detected in the Philippines in the 1980s [Taniguchi et al., 1990; Urasawa et al., 1990]. Since 2000, G12 HRV strains have been reported in Japan, Thailand, USA, India, Bangladesh (accession number DQ482723), and Argentina [Griffin et al., 2002; Pongsuwanna et al., 2002; Das et al., 2003; Shinozaki et al., 2004; Castello et al., 2006; Samajdar et al., 2006]. Two of the most recent reports have come from surveillance studies conducted in Argentina and eastern India, where G12 HRV strain was found in 6.7% and 17.1% of samples, respectively, suggesting that this is an emerging rotavirus strain [Castello et al., 2006; Samajdar et al., 2006].

In this study, the recently reported G12 strains [Ramani et al., 2007] from children in South India have been characterized by VP4 typing by PCR and partial sequence analysis of the genes encoding VP7, VP6, and NSP4. The evaluation of a modified multiplex G-typing PCR incorporating a newly designed G12-specific primer is also described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens

As part of an ongoing community based rotavirus surveillance study, fecal samples were collected from children in a birth cohort from an urban slum in Vellore, South India. Stool samples were also obtained from children admitted with acute gastroenteritis as part of a rotavirus surveillance study at the Christian Medical College, Vellore, South India. Cohort monitoring, fecal sample collection and screening for rotavirus were conducted as described previously [Banerjee et al., 2006]. Viral RNA was extracted from 10% fecal suspensions of all rotavirus positive stool samples using guanidium isothiocyanate-silica [Boom et al., 1990]. Complementary DNA was synthesized from the extracted viral RNA using reverse transcriptase enzyme in the presence of random hexamers. Rotavirus strains were further characterized by VP7- and VP4-specific multiplex hemi-nested RT-PCRs as described previously [Gouvea et al., 1990; Gentsch et al., 1992; Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2004].

Sequencing of VP7 Genes

A total of 13 samples from which the G type was not determined after the second round of G-typing multiplex PCR using type specific primers [Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2004], but which had a fragment of 881 bp of the VP7 gene amplified in the first round PCR using VP7 consensus primers [Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2004] were sequenced as described [Ramani et al., 2007]. The PCR amplicons obtained in the first round of the VP7 specific RT-PCR were purified and sequenced in both directions with the ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using the same primer pairs as in the VP7 first round PCR reaction. Sequences were resolved in the automated DNA sequencer, the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and electropherograms were analyzed using sequencing analysis software (version 1.01, Applied Biosystems).

Sequencing of VP6 and NSP4 Genes

Amplicons of the genes encoding the VP6 gene of G12 rotavirus strains with P[6] and P[8] specificities were sequenced using the oligonucleotide primers VP6-F (5′-GACGGVGCRACTACATGGT-3′; nt 747-766) VP6-R (5′-GTCCAATTCATNCCGGTGG-3′; nt 1,126-1,106) which amplified a 379 bp region [Iturriza Gomara et al., 2002]. Sequencing was also carried out for the NSP4 gene of G12P[6] and G12P[8] strains using the primers NSP4-F′ (5′-GGCTTTTAAAAGTTCTGTTCCG-3′; nt 1-22)-NSP4-R (5′-GTCACACTAAGACCATTCC-3′; nt 753-732) which amplified a 743 bp region of the NSP4 gene [Ciarlet et al., 2000].

Sequence Analysis

The nucleotide sequences were aligned with corresponding gene sequences of selected rotavirus strains available in the GenBank or the European rotavirus typing database (http://193.129.245.237/bionumerics/rotavirus/home.php). Multiple alignments and phylogenetic analysis were performed using the Clustal W algorithm and Neighbor Joining methods of the Bioedit software package (http://www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html) (version 7.0.5.3) and tree was drawn with Tree View Version 1.6.6 (http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/treeview.html), and Bionumerics (Applied Maths, Kortrij, Belgium). The dendrograms were confirmed by at least two of the following methods; neighbor joining, maximum parsimony, and maximum likelihood. Genetic lineages were defined when bootstrap values (generated from1,000 pseudoreplicates) were >95%.

The VP7 nucleotide sequences of the Vellore G12 strains CRI 32215, CRI 32548, CRI 32920, CRI 32608, CRI 33015, CRI 32609, CRI 32442, CRI 32742, RV 404, RV 412, RV 413, RV 417, and RV 430 were submitted to GenBank database and the accession numbers are DQ785512-DQ785524, respectively. The NSP4 sequence accession numbers are DQ909067 (RV 412), DQ909068 (RV 430), DQ909069 (CRI 32608), and DQ909070 (CRI 32609). The VP6 sequence accession numbers are DQ909060 (CRI 32215), DQ909061 (CRI 32608), DQ909062 (CRI 32609), DQ909063 (CRI 33015), DQ909064 (RV 413), DQ909065 (RV 412), and DQ909066 (RV 430).

Modification of Multiplex RT-PCR for VP7 Genotyping to Include a New G12 Primer

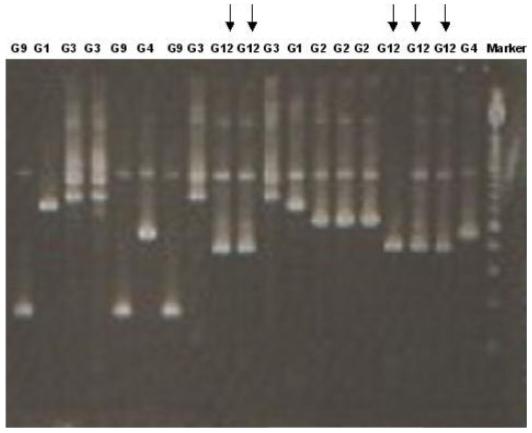

A new G12-specific primer was designed using multiple alignments of the VP7 gene sequences of all the G12 strains from the present study and published VP7 gene sequences of other G12 strains from the GenBank database. VP7 gene sequences of representative prototype strains of G1, G2, G3, G4, G8, G9, and G10 were included in the alignment. A 20 bp G12 primer (5′-CCGATGGACGTAACGTTGTA-3′, nt 548-567) was selected from a region of the multiple alignments that was highly conserved amongst the G12 strains but was variable among the other G types. BLAST searches were performed to ensure that the G12 type-specific primer was only complementary to the G12 VP7 gene segment. The new G12 type-specific primer was used in the multiplex second round reactions which included primers for the remaining G types. The inclusion of this primer in the multiplex reaction yielded an amplicon of 387 bp, of sufficiently different size to allow differentiation among genotypes and identification of strains of the G12 genotype (Fig. 1). The specificity of the multiplex PCR was tested using a panel of random-primed cDNA derived from G1, G2, G4, G8, G9, G10, and G12 rotavirus strains (two of each strain and thirteen G12 strains) characterized in Vellore from a community based birth cohort study [Banerjee et al., 2006] and also rotavirus positive samples characterized in United Kingdom (five G1, four G2, four G3, three G4, and five G9) as part of an ongoing European rotavirus surveillance study (M. Iturriza-Gomara, personal communication). The modified multiplex PCR was also verified using 40 rotavirus positive samples which were untyped previously for the VP7 gene.

Fig. 1.

Human rotavirus gene 9. Illustration of VP7 specific primer positions and type-specific amplicon sizes after incorporation of the new G12 primer in the VP7 multiplex PCR. The size of the expected product of amplification from first round amplification is 881 bp. The second round amplification products for gene 9 typing PCR are 754 bp (G8), 682 bp (G3), 618 bp (G1), 521 bp (G2), 452 bp (G4), 387 bp (G12), 266 bp (G10), and 179 bp (G9).

RESULTS

Sequence Analysis of the VP7 Encoding Gene

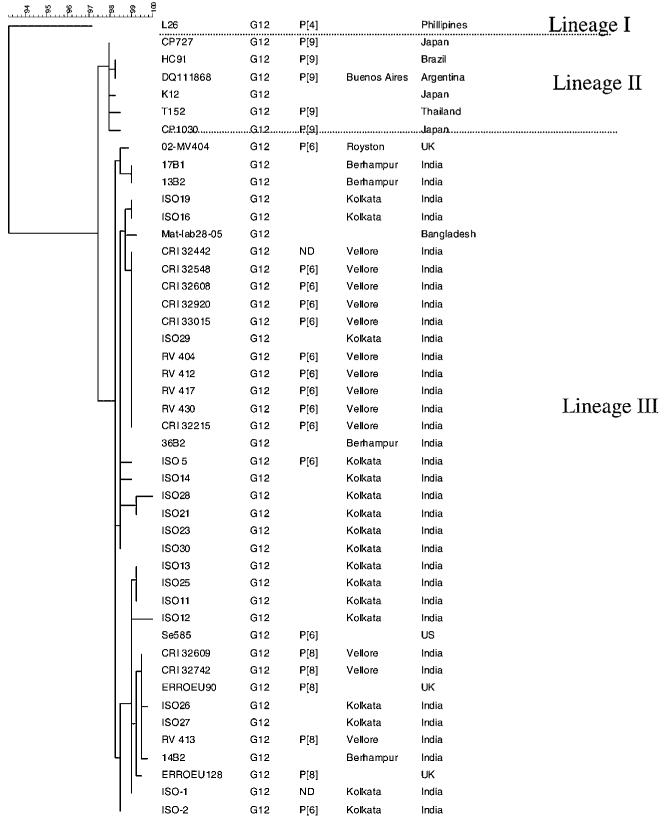

Multiple sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of the partial VP7 gene sequence of 13 untyped strains identified them as G12 HRV strains, as reported [Ramani et al., 2007]. Further characterization by analysis of the partial nucleotide sequence of all 13 strains (CRI 32215, CRI 32442, CRI 32548, CRI 32608, CRI 32609, CRI 32742, CRI 32920, CRI 33015, RV 404, RV 412, RV 413, RV 417, and RV 430) showed maximum homology with the Indian ISO-5 G12 strain (97-99% at the nucleotide level and 97-99% at the deduced amino acid level). They showed less homology with the prototype G12 strain L26 (89-90% identity at the nucleotide level and 90-94% at the deduced amino acid level). Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that all human G12 strains clustered in three lineages as defined by bootstrap values >95% (Fig. 2). Lineage I contained the prototype strain L26. Strains from Thailand, Brazil Argentina, and Japan comprised lineage II. Lineage III had strains from the US, India, Bangladesh, and the UK, and shared >96% homology at the nt level and aa levels. All G12 strains analyzed in this study clustered in lineage III.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree constructed using the maximum parsimony method and sequences of the VP7 encoding gene of the human G12 rotavirus strains form Vellore and of other strains, available in GenBank or the European rotavirus genotyping database. The name or reference number of the strains is indicated in the first column, G and P types are indicated in the second and third columns, respectively, and the geographical origin of the strains is indicated in the last two columns.

P types determined in 12 of the 13 G12 strains from Vellore as reported separately [Ramani et al., 2007], were P[6] in 9 strains (69.2%) and, P[8] in 3 strains (23.1%), with one sample remaining untyped for VP4 (Table I). Since a first round amplification product of the VP4 gene could not be obtained for the untyped sample, sequence analysis was not possible. In previous studies, the P type associated with the L26 strain (lineage I) was P[4]. The association with Lineage II (Argentinean, Japanese, and Thai strains) was P[9]. In Lineage III, the US strain, Se585 had an association with P[6] whereas P[6] and P[8] were predominantly associated with the Indian strains (Fig. 2) [Samajdar et al., 2006; Ramani et al., 2007].

TABLE I.

Association of P Types, VP6 Genogroups and NSP4 Genotypes With the Vellore G12 Strains

| G12 strains | G type | P type | VP6 genogroup | NSP4 genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRI 32215 | G12 | P[6] | SGII | — |

| CRI 32442 | G12 | UT | — | — |

| CRI 32548 | G12 | P[6] | — | — |

| CRI 32608 | G12 | P[6] | SGII | NSP4 B |

| CRI 32609 | G12 | P[8] | SGII | NSP4 B |

| CRI 32742 | G12 | P[8] | — | — |

| CRI 32920 | G12 | P[6] | — | — |

| CRI 33015 | G12 | P[6] | SGII | — |

| RV 404 | G12 | P[6] | — | — |

| RV 413 | G12 | P[8] | SGII | — |

| RV 412 | G12 | P[6] | SGII | NSP4 B |

| RV 417 | G12 | P[6] | — | — |

| RV 430 | G12 | P[6] | SGII | NSP4 B |

UT, untyped; —, not done.

Sequence Analysis of the Genes Encoding NSP4 and VP6

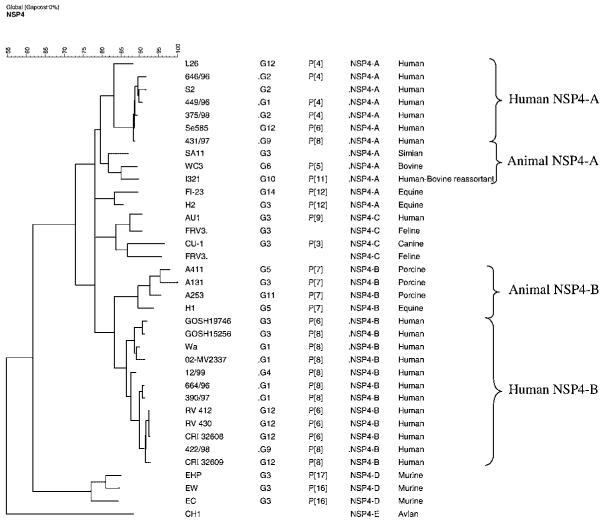

The partial nucleotide sequence of the NSP4 gene of 4 Vellore G12 HRV strains were compared with other representative NSP4 sequences of genogroups A, B, C, D, and E. All four NSP4 sequences analyzed clustered within the NSP4-B genotype with human strains (Fig. 3, Table I). On doing BLAST homology search they showed maximum identity to the NSP4 sequence of strain V1352 (accession number AB196959) isolated from Kolkata (97-98 % identity at the nucleotide level), which has been isolated from human feces and also has NSP4 B specificity. The NSP4 sequences of the Vellore G12 strains were found to be distinct from the porcine G12 rotavirus strain RU172 of NSP4 genotype B with an animal lineage.

Fig. 3.

Dendogram constructed by using NSP4 nucleotide sequences of the G12 rotavirus strains using the maximum parsimony method. Sequences representative of the different existing NSP4 genotypes were included for comparison. The name or reference number of the strains is indicated in the first column, G and P types are indicated in the second and third columns, respectively, the NSP4 genotype is in the third column, and the species from which the strain was obtained is indicated in the last column.

The Vellore G12 strains were SGII by sequence analysis of a 379-bp fragment of the gene encoding VP6 (Fig. 4) and were closely related to VP6 sequences of other common HRV strains. By BLAST homology search they were found to share maximum identity to the HRV sequences rj8200/04 (accession number DQ498163) and RMC/G66 (accession number AY601553) reported from Rio Di Janeiro and Manipal (nucleotide level identity of 99-98%).

Fig. 4.

Dendogram constructed with the maximum parsimony method using rotavirus VP6 partial sequences derived from G12 strains and other representative strains from GenBank and the European rotavirus genotyping database. The name or reference number of the strains is indicated in the first column, G and P types are indicated in the second and third columns, respectively, the subgroup is in the fourth column, and the geographical origin of the strains is indicated in the last two columns.

Incorporation of the G12 Specific Primer Into the Multiplex Genotyping PCR

The new G12 type-specific primer was used in the second round of the VP7 specific multiplex PCR with G typing primers for G1-4, G8, G9, and G10, using the reaction conditions previously described [Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2004]. All rotavirus strains including the panel of strains genotyped previously belonging to G-types G1, G2, G3, G4, and G9 as well as the South Indian and European G12 strains were identified using this PCR, and amplicons of the expected sizes were obtained in all cases (Fig. 5). When samples of VP7 gene untyped previously and collected during the period June to September 2005 in India (a set of 30 untyped samples) and as part of the European surveillance (a set of 10 untyped samples) were tested using the new G12 primer in a VP7 multiplex PCR, one new G12 stain was identified among the Vellore rotavirus positive untyped samples and 10 new G12 strains were identified from the UK rotavirus positive untyped samples.

Fig. 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products from the second round of VP7 specific multiplex RT-PCR. A panel of rotavirus strains of other genotypes, as well as the G12 strains, were identified after incorporation of the new G12 primer in the multiplex PCR.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of the G12 strain in southern India in 2005, following a report from eastern India has some historical parallels with the emergence and subsequent spread of G9 strains. G9 strains were first reported in the USA in 1983 [Gouvea et al., 1990], and this was followed by no further reports of this strain for more than a decade [Ramachandran et al., 1998]. In the mid 1990s, G9P[6] and G9P[8] strains were reported in India, Japan, the UK, and the US, and subsequently G9P[8] spread globally accounting currently for 4.1% of all rotavirus infections globally [Santos and Hoshino, 2005]. Only continuing surveillance will determine whether the same phenomenon will be seen with the G12 strains. A recent report from this region did not find this strain in hospitalized children or children in the community prior to 2005 [Banerjee et al., 2006]. The emergence of this rotavirus strain in the population in 2005 is supported by epidemiological data showing clustering by spatial analysis [Ramani et al., 2007].

A G12 primer was designed from the sequence analysis of the G12 strains, and incorporated into the existing multiplex genotyping PCR [Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2004]. The specificity of the PCR was evaluated using a panel of known rotavirus genotypes, and strains of all commonly circulating genotypes were identified with demonstration of amplicons of expected sizes. This primer differs from the primers described previously from India [Samajdar et al., 2006] but is specific for all known G12 strains. The incorporation of a G12-specific primer into the genotyping protocols in surveillance studies may uncover hitherto unidentified G12 rotavirus infections throughout the world, as was seen when the modified PCR methodology was applied to untyped samples obtained from surveillance studies in India and Europe.

Genetic characterization of the gene encoding the VP7 was carried out in order to study the relationships among the G12 strains found in Vellore and those reported elsewhere. The strains from Vellore clustered with strains isolated in eastern India, in the US, Bangladesh, and the UK. The VP7 sequence diversity found among the G12 strains from different parts of the world may suggest different introductions of G12 strains into human populations.

G12 strains have been found in association with multiple VP4 types, namely P[4], P[6], P[8], and P[9]. The first human G12 reported in the Philippines was associated with a VP4 of P[4] in the 1980s. G12 rotaviruses found in the far East and South America, were all associated with P[9], and were closely related to each other within lineage II [Pongsuwanna et al., 2002; Shinozaki et al., 2004; Castello et al., 2006]. The G12 strains reported from the US, UK, Bangladesh, and India from 2002 cluster within lineage III, and the lack of diversity within the gene encoding the VP7 suggests both a common ancestor and a recent introduction [Griffin et al., 2002; Das et al., 2003]. However, the association of G12 strains within lineage III with different P types, P[4], P[6], and P[8] suggests reassortment among commonly circulating strains. The increased reporting of infections with G12 may be associated with reassortment resulting in generation of a strain which is better adapted to replication in humans, similar to the events that preceded the spread of G9 strains in the last decade.

The origin of these G12 strains is unclear. The association of the G12 strains in lineage II with P[9] may suggest a zoonosis; P[9] strains have been associated with feline rotaviruses [Griffin et al., 2002; Pongsuwanna et al., 2002]. However, to date only a single G12 strain has been reported in a host other than human, a G12P[7] strain isolated from a pig in Kolkata [Ghosh et al., 2006]. The sequence of this strain is distantly related to human G12 strains and does not segregate with any of the three lineages described. Northern blot hybridization analysis suggested that the G12 strains from Japan and Thailand (CP727, CP1030, and T152) were reassortants of a L26 like strain and a AU-I genogroup strain (G3) [Shinozaki et al., 2004]. Similar analysis for the ISO-1 and Se585 suggested that they may also be reassortants between L26 and strain US1205, a strain closely related to those in the DS-1 genogroup (G2) [Griffin et al., 2002]. This supports the premise that animal strains may enter frequently into the human population but can only be sustained by reassortment with human strains which confer a replicative advantage.

Analysis of the NSP4 and/or VP6 can be a useful tool for tracing zoonotic introduction of rotaviruses. NSP4 genotypes have been shown to segregate according to their species of origin suggesting distinct evolutionary patterns of circulating rotaviruses [Ciarlet et al., 2000]. Additionally, linkage has been demonstrated between NSP4 genotype and VP6 subgroup in HRVs by analysis of a range of common and reassortant strains, including 38 strains from Vellore, where genes encoding SGI always co-segregate with NSP4-A, and SGII with NSP4-B [Iturriza-Gomara et al., 2003]. The G12 strains from Vellore belonged to VP6 SGII and NSP4 B genotype, which is consistent with our previous findings. The sequences derived from the genes encoding NSP4 and VP6 of the G12 strains found in Vellore have a HRV origin, which again suggests reassortment. In order to elucidate the origin of G12 strains, more comprehensive surveillance of animal rotavirus strains is necessary. A more comprehensive characterization of rotavirus strains, which includes analysis of the genes encoding the NSP4 and/or VP6 of “novel” strains, particularly when they are first detected in any population, could allow further characterization of possible zoonotic infection and, in combination with surveillance of human and animal populations, permit tracking of rotaviral reassortment and evolution.

The possible zoonotic transmission of rotavirus strains allied to reassortment with human strains resulting in novel antigenic combinations is a significant challenge for vaccine development. Two newly introduced vaccines have been evaluated in large clinical trials [Ruiz-Palacios et al., 2006; Vesikari et al., 2006]. The first vaccine, Rotarix™ is an attenuated G1P1A[8] virus strain whereas Rotateq™ is a naturally attenuated bovine-human reassortant vaccine containing VP7 proteins of the G1, G2, G3, and G4 strains and the VP4 protein of the P1A[8] strain. The efficacy of these vaccines has not been studied in populations where there are large proportions of circulating rotavirus strains not included in the vaccines and very marked diversity of strains. Unless these vaccines induce a significant heterotypic response, adequate protection, and vaccine efficacy may not be achieved in these populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust under the Trilateral Cooperative Initiative for Research in Infectious Diseases in the Developing World (grant number 063144).

Grant sponsor: Wellcome Trust; Grant number: 063144.

REFERENCES

- Ball JM, Tian P, Zeng CQ, Morris AP, Estes MK. Age-dependent diarrhea induced by a rotaviral nonstructural glycoprotein. Science. 1996;272:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee I, Ramani S, Primrose B, Moses P, Iturriza-Gomara M, Gray JJ, Jaffar S, Monica B, Muliyil JP, Brown DW, Estes MK, Kang G. Comparative study of the epidemiology of rotavirus in children from a community-based birth cohort and a hospital in South India. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2468–2474. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01882-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boom R, Sol CJ, Salimans MM, Jansen CL, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello AA, Arguelles MH, Rota RP, Olthoff A, Jiang B, Glass RI, Gentsch JR, Glikmann G. Molecular Epidemiology of Group A Rotavirus Diarrhea among Children in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from 1999 to 2003 and Emergence of the Infrequent Genotype G12. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2046–2050. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02436-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarlet M, Liprandi F, Conner ME, Estes MK. Species specificity and interspecies relatedness of NSP4 genetic groups by comparative NSP4 sequence analyses of animal rotaviruses. Arch Virol. 2000;145:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s007050050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe NA, Gondwe JS, Broadhead RL, Molyneux ME, Woods PA, Bresee JS, Glass RI, Gentsch JR, Hart CA. Rotavirus G and P types in children with acute diarrhea in Blantyre, Malawi, from 1997 to 1998: Predominance of novel P[6]G8 strains. J Med Virol. 1999;57:308–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Varghese V, Chaudhury S, Barman P, Mahapatra S, Kojima K, Bhattacharya SK, Krishnan T, Ratho RK, Chhotray GP, Phukan AC, Kobayashi N, Naik TN. Emergence of novel human group A rotavirus G12 strains in India. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2760–2762. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2760-2762.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes M. Rotaviruses and their replication. In: Fields BN, DMK, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 3rd edition Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1625–1655. [Google Scholar]

- Gentsch JR, Glass RI, Woods P, Gouvea V, Gorziglia M, Flores J, Das BK, Bhan MK. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1365-1373.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, Varghese V, Samajdar S, Bhattacharya SK, Kobayashi N, Naik TN. Molecular characterization of a porcine Group A rotavirus strain with G12 genotype specificity. Arch Virol. 2006;151:1329–1344. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0714-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouvea V, Glass RI, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark HF, Forrester B, Fang ZY. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin DD, Nakagomi T, Hoshino Y, Nakagomi O, Kirkwood CD, Parashar UD, Glass RI, Gentsch JR. Characterization of nontypeable rotavirus strains from the United States: Identification of a new rotavirus reassortant (P2A[6],G12) and rare P3[9] strains related to bovine rotaviruses. Virology. 2002;294:256–269. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriza Gomara M, Wong C, Blome S, Desselberger U, Gray J. Molecular characterization of VP6 genes of human rotavirus isolates: Correlation of genogroups with subgroups and evidence of independent segregation. J Virol. 2002;76:6596–6601. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6596-6601.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriza Gomara M, Kang G, Mammen A, Jana AK, Abraham M, Desselberger U, Brown D, Gray J. Characterization of G10P[11] rotaviruses causing acute gastroenteritis in neonates and infants in Vellore, India. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2541–2547. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2541-2547.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriza-Gomara M, Green J, Brown DW, Desselberger U, Gray JJ. Comparison of specific and random priming in the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for genotyping group A rotaviruses. J Virol Methods. 1999;78:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriza-Gomara M, Anderton E, Kang G, Gallimore C, Phillips W, Desselberger U, Gray J. Evidence for genetic linkage between the gene segments encoding NSP4 and VP6 proteins in common and reassortant human rotavirus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3566–3573. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3566-3573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriza-Gomara M, Kang G, Gray J. Rotavirus genotyping: Keeping up with an evolving population of human rotaviruses. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapikian AZ, Hoshino Y, Chanock RM. Rotaviruses. In: Knipe H DM, editor. Fields virology. 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lippin-cott-Raven Publishers; 2001. pp. 1787–1833. H. [Google Scholar]

- Martella V, Ciarlet M, Banyai K, Lorusso E, Cavalli A, Corrente M, Elia G, Arista S, Camero M, Desario C, Decaro N, Lavazza A, Buonavoglia C. Identification of a novel VP4 genotype carried by a serotype G5 porcine rotavirus strain. Virology. 2006;346:301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar UD, Gibson CJ, Bresse JS, Glass RI. Rotavirus and severe childhood diarrhea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:304–306. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pongsuwanna Y, Guntapong R, Chiwakul M, Tacharoenmuang R, Onvimala N, Wakuda M, Kobayashi N, Taniguchi K. Detection of a human rotavirus with G12 and P[9] specificity in Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1390–1394. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1390-1394.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran M, Das BK, Vij A, Kumar R, Bhambal SS, Kesari N, Rawat H, Bahl L, Thakur S, Woods PA, Glass RI, Bhan MK, Gentsch JR. Unusual diversity of human rotavirus G and P genotypes in India. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:436–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.436-439.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran M, Gentsch JR, Parashar UD, Jin S, Woods PA, Holmes JL, Kirkwood CD, Bishop RF, Greenberg HB, Urasawa S, Gerna G, Coulson BS, Taniguchi K, Bresee JS, Glass RI. Detection and characterization of novel rotavirus strains in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3223–3229. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3223-3229.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani S, Banerjee I, Gladstone BP, Sarkar R, Selvapandian D, Le Fevre AM, Jaffar S, Iturriza-Gomara M, Gray JJ, Estes MK, Brown DW, Kang G. Geographic information systems and genotyping in the identification of rotavirus G12 infections in an urban slum with subsequent detection in hospitalized children: Emergence of G12 genotype in south India. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:432–437. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01710-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palacios GM, Perez-Schael I, Velazquez FR, Abate H, Breuer T, Clemens SC, Cheuvart B, Espinoza F, Gillard P, Innis BL, Cervantes Y, Linhares AC, Lopez P, Macias-Parra M, Ortega-Barria E, Richardson V, Rivera-Medina DM, Rivera L, Salinas B, Pavia-Ruz N, Salmeron J, Ruttimann R, Tinoco JC, Rubio P, Nunez E, Guerrero ML, Yarzabal JP, Damaso S, Tornieporth N, Saez-Llorens X, Vergara RF, Vesikari T, Bouckenooghe A, Clemens R, De Vos B, O’Ryan M. Safety and efficacy of an attenuated vaccine against severe rotavirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:11–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samajdar S, Varghese V, Barman P, Ghosh S, Mitra U, Dutta P, Bhattacharya SK, Narasimham MV, Panda P, Krishnan T, Kobayashi N, Naik TN. Changing pattern of human group A rotaviruses: Emergence of G12 as an important pathogen among children in eastern India. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos N, Hoshino Y. Global distribution of rotavirus serotypes/genotypes and its implication for the development and implementation of an effective rotavirus vaccine. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15:29–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Okada M, Nagashima S, Kaiho I, Taniguchi K. Characterization of human rotavirus strains with G12 and P[9] detected in Japan. J Med Virol. 2004;73:612–616. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Urasawa T, Kobayashi N, Gorziglia M, Urasawa S. Nucleotide sequence of VP4 and VP7 genes of human rotaviruses with subgroup I specificity and long RNA pattern: Implication for new G serotype specificity. J Virol. 1990;64:5640–5644. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5640-5644.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unicomb LE, Podder G, Gentsch JR, Woods PA, Hasan KZ, Faruque AS, Albert MJ, Glass RI. Evidence of high-frequency genomic reassortment of group A rotavirus strains in Bangladesh: Emergence of type G9 in 1995. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1885–1891. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1885-1891.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urasawa S, Urasawa T, Wakasugi F, Kobayashi N, Taniguchi K, Lintag IC, Saniel MC, Goto H. Presumptive seventh serotype of human rotavirus. Arch Virol. 1990;113:279–282. doi: 10.1007/BF01316680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesikari T, Matson DO, Dennehy P, Van Damme P, Santosham M, Rodriguez Z, Dallas MJ, Heyse JF, Goveia MG, Black SB, Shinefield HR, Christie CD, Ylitalo S, Itzler RF, Coia ML, Onorato MT, Adeyi BA, Marshall GS, Gothefors L, Campens D, Karvonen A, Watt JP, O’Brien KL, DiNubile MJ, Clark HF, Boslego JW, Offit PA, Heaton PM. Safety and efficacy of a pentavalent human-bovine (WC3) reassortant rotavirus vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]