Abstract

Objective

We aimed to investigate associations between work disability and illness perceptions, over and above medical assessment and self-reported health.

Methods

A representative sample of people aged 15–64 years with various chronic physical diseases was derived from the Panel of Patients with Chronic Diseases in the Netherlands. In this group, 189 patients were fully work-disabled and 363 were employed. In this cross-sectional study, associations between medical health status stated by the general practitioner, self-reported health, and illness perceptions about the consequences of the illness, the timeline (cyclical vs. chronical), control (treatment and personal), coherence and three causal dimensions (psychological, risk factors and immunity) and work disability were investigated. These associations were investigated in three separate steps using multivariate logistic regression analyses, with the employed patients as a reference group. All models were corrected for age, sex, and level of education.

Results

In the second multivariate model containing medical health status and self-perceived health, complete work disability was significantly associated with more fatigue (OR 2.42), more self-perceived functional limitations (OR 11.94), higher age, female sex, and lower education. Medical health status was not significantly associated with work disability. After adding illness perceptions to this model, the percentage of explained variance for work disability increased from 65 to 77%. In this final model, work disability was significantly associated with the patient’s perception that the consequences of the disease were more severe (OR 5.34), and also with more self-perceived functional limitations (OR 14.27), lower education, being female, and a higher age. Illness perceptions and self-reported health status were significantly associated with work disability.

Conclusion

We conclude that illness perceptions are significantly associated with work disability in the chronically ill. Self-reported health is more strongly associated with work disability than the assessment of health status by the physician.

Keywords: Employment, Chronic disease, Adaptation, Psychological, Disability evaluation

Introduction

Chronic illness is often associated with serious limitations in the activities of daily life in general and work disability in particular. Previous studies have shown that the chronically ill experience more difficulties in finding a job and have a higher risk of becoming work-disabled (Pinder 1995; NCCZ 1995; Ware 1998). In the Netherlands, one out of three people between the age of 18 and 65 with a chronic illness is involved in paid labor, compared to two out of three people in the general population in 2003 (Heijmans et al. 2005). A recent study has indicated that complete work disability among the chronically ill is primarily related to pain, fatigue, and physical limitations, which can be considered common consequences of chronic illness (Baanders et al. 2002). In this study, there was no independent effect of the specific disease diagnosis, which suggests that having a chronic disease in general might be more important for labor participation than the nature of the specific disease itself. Although health complaints such as pain, fatigue, and physical limitations resulting from chronic illness explained a large part of the differences between people who are work disabled or employed, an essential part of these differences remained unexplained (Baanders et al. 2002).

Studies on adaptation to chronic illness have shown that there often is a considerable discrepancy between the level of illness-related dysfunction as reported by patients and the underlying pathology of their disease. The magnitude of the physical, mental, and social problems that patients with chronic diseases present can vary greatly from patient to patient, even in patients with the same medical condition or the same severity of disease. The weak relationship between biomedical parameters and physical, mental, and social wellbeing has given rise to hypotheses about the contribution of psychosocial factors to health outcomes in patients with chronic diseases. In recent years, the role of illness perceptions and coping responses of patients have especially been highlighted. Health psychologists have shown that, to make sense and respond to the problems caused by a chronic illness, patients create their own explanations or ‘beliefs’ on their illness. One of the strong supporting models in this area is the self-regulation model (SRM) of Leventhal et al. (1984). The SRM suggests that health-related behaviors and health-related outcomes such as quality of life are heavily influenced by the patient’s own beliefs or representations of the illness. Illness perceptions are beliefs about what caused the illness, how long it will last, its expected effects, and controllability, and also include the emotional reaction to the illness (Leventhal et al. 1984, 1997). Research has shown that illness perceptions affect coping (Heijmans 1998b; Moss-Morris et al. 1996), functional adaptation (Heijmans 1998a; Petrie et al. 1996; Pimm and Weinman 1998) and adherence to a wide range of medical recommendations (Horne et al. 2001). For example, believing that an illness will be lengthy, severe, and uncontrollable is associated with poorer functioning and increased pain in people with arthritis (Hampson et al. 1994). In several other studies, it was found that workers’ perceptions of illness were predictive for the speed of return to work (Petrie et al. 1996; Cuelunaere et al. 1999).

So far there have been no studies exploring the role of illness perceptions in relation to work disability in patients with chronic diseases. Since the group of chronic patients that is unemployed may have a large variety of reasons for being unemployed, major differences can be expected between employed patients and fully work-disabled patients. From the above, it can be concluded that it will be interesting to investigate the role of illness perceptions as determinants of work disability or employment in the chronically ill.

This study aims to investigate associations between complete work disability in people with chronic diseases and illness perceptions, medically assessed, and self-reported health. In addition, we aimed to investigate the added value of illness perceptions over and above the associations between medically assessed and self-reported health and complete work disability. As previous research has indicated that being employed is primarily related to generic problems of chronic disease such as pain and functional limitations (Baanders et al. 2002), the study was conducted on data gathered from people with all kinds of physical chronic diseases.

The hypothesis to be tested in this study is ‘Negative illness perceptions are associated with being fully work-disabled in chronically ill patients in addition to medically assessed and self-reported health.’

Methods

Participants

Employed and full work-disabled chronically ill patients were selected from a national database of medically diagnosed chronic patients, the Panel of Patients with Chronic Diseases (PPCD; N = 2,484). The response to the questionnaire was 89.8% (n = 2,230). The PPCD is a prospective nationwide representative panel-study on the consequences of chronic illness in the Netherlands (Rijken et al. 2005). All patients in this panel were selected from 51 general practices in the Netherlands according to the following criteria: a diagnosis of a physical chronic disease by a certified medical practitioner, an age ≥15, being noninstitutionalized, being aware of their diagnosis, not being terminally ill, being mentally and physically able to participate, and having a sufficient mastery of the Dutch language. The sample of 51 practices appeared to differ slightly from the total population of practices in the Netherlands with respect to urbanization level and region of their place of residence. To correct for these differences, a weighting factor was calculated and all analyses were conducted on the weighted sample (Baanders et al. 2002).

Using a cross-sectional design, we analyzed data collected in October 2001 (first survey) and medical data of the panel members provided by their GPs at inclusion. The study sample was confined to patients aged 15–64 who were either employed [in accordance with the definition of Statistics Netherlands (1998) for 12 h or more per week] or fully work-disabled according to the Netherlands Disability Act (NDA) (n = 1,002). The NDA defines work disability as a loss of income. When a person can only fulfil a job in which he earns 20% or less than his previous income, he becomes completely work-disabled.

All other panel members aged 15–64 were excluded from this study because of various reasons for unemployment (n = 450). Being unemployed may be a free choice, e.g., when raising children, but it can also be a choice driven by health problems. Our study sample therefore consisted of 552 chronic disease patients: 363 employed and 189 fully work-disabled.

Measures

The socio-demographic characteristics included in this study were gender, age, and educational level. Educational level was defined as the highest level of completed education and was divided into three categories: low (primary education, lower secondary, and lower vocational education), middle (intermediate secondary and intermediate vocational education), and high (higher vocational education and university). Besides these socio-demographic characteristics, illness duration and the presence of comorbidities, both registered by the GP at inclusion, were included.

Medical health status of each participant was assessed by the GP on four disease characteristics: life threat, progressive deterioration, changing course, and controllability by medical care. Scores for each characteristic ranged from 1 (not at all present) to 3 (very much present) (Heijmans et al. 2001). These variables were dichotomized into ‘not present’ (score 1) and present (scores 2 and 3). Since the item on medical controllability was defined opposite, this item was dichotomized into ‘slightly present’ (scores 1 and 2) and ‘very much present’ (score 3).

Self-reported health status was assessed using a questionnaire from the Social and Cultural Planning office of the Netherlands (SCP). This questionnaire was completed by the patient and aimed to measure the presence of functional limitations in seven domains: sitting and standing, arm and hand use, personal care, walking, housekeeping activities, hearing, and vision. A total score was calculated by combining the score on each of the earlier-mentioned domains, resulting in four categories: none, light, moderate, and severe functional limitations (Heijmans et al. 2005; NCCZ 1995).

In addition, patients were asked to assess their level of pain and fatigue by means of single items: ‘My health status as a whole is characterized by pain’ and ‘My health status as a whole is attended with fatigue.’ Response format for both items was as follows: (1) not at all, (2) to a certain extent, and (3) to a large extent. For both items, scores 1 and 2 were merged to obtain two dichotomous variables.

To measure illness perceptions, we used the Illness Perception Questionnaire—Revised version (IPQ-R; Moss-Morris et al. 2002) addressing beliefs about consequences (e.g. ‘My illness is a serious condition’; six items; Cronbach’s α = 0.84), a chronic timeline (e.g. ‘My illness will last for a long time’; six items; α = 0.85), a cyclical timeline (e.g. ‘My symptoms come and go in cycles’; four items; α = 0.77), treatment control (e.g. ‘My treatment will be effective in curing my illness’; five items; α = 0.73), personal control (e.g. ‘I have the power to influence my illness’; six items; α = 0.78), and coherence, i.e., to what extent the patient has a coherent understanding of her illness (e.g. ‘I have a clear picture or understanding of my condition’; five items; α = 0.82). All subscales were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ Higher scores on these subscales refer to a stronger belief in serious consequences of the disease; a stronger belief in a chronic or more changing time course; a stronger belief that the illness is controllable either by self-care or medical care; and a better understanding of the illness, respectively.

Beliefs about what caused the illness were assessed by 18 items, each representing a possible cause. The items were also scored on a five-point scale; higher scores refer to a stronger belief in that particular cause (Moss-Morris et al. 2002). A forced four-factor analysis was conducted on all 18 items. Using varimax rotation and eigen-values >1, the four factors explained 52.1% of the variance. Stress, mental attitude, family problems, overwork, emotional state, and personality constituted the psychological attribution scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.84); germ or virus, pollution in the environment, and altered immunity combined to form the immunity scale (α = 0.57). The items diet or eating habits, poor medical care in past, own behavior, ageing, smoking, and alcohol combined to form the risk factors-scale. One item (‘hereditary—it runs in the family’) was removed from the risk factors-scale to increase internal validity (Cronbach’s α after item removal was 0.64). Internal validity of the fourth subscale, accident or chance, was too low to consider this scale for further analyses (α = 0.20). So, three scales distracted from the causal dimension were used for further analyses: psychological attributions, immunity, and risk factors.

All subscales of the illness perception questionnaire form a coherent group of subscales. This group of subscales should be considered together to gain insight in illness perceptions. Which subscale is associated with the dependent variable is less important than the (possible) finding that illness perceptions as a group are associated with the dependent variable.

Analysis

In this cross-sectional study, comparisons were made between the employed and the fully work-disabled. First, bivariate analyses were conducted using the chi-square statistic and Student’s t tests to test differences between the two groups in socio-demographic characteristics and medical health status, self-reported health status, and illness perceptions.

Next, logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate associations between complete work-disabled and the independent variables. We entered four blocks of variables using the Enter method, in which all variables from each block are retained in the models: (1) socio-demographic characteristics, (2) medical health status, (3) self-reported health status, and (4) illness perceptions. In the first model, the socio-demographic characteristics and the variables assessing medical health status were included. In the second model, we added the self-reported health variables. Finally, in the third model, we added the illness perception variables. Correlation coefficients between the independent variables in both groups were all lower than 0.65. By building the final model in three steps, we were able to assess the added value of the associations between self-reported health and illness perceptions and work disability or employment, in addition to the socio-demographic characteristics and medical health status. The additional value of including blocks of variables to the regression model was investigated by the change in Nagelkerke R 2, a measure for explained variance in logistic regression analysis (Field 2000). The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (version 11.5).

Results

The employed chronically ill were more often male, younger, and higher educated compared to the fully work-disabled chronically ill (Table 1). In addition, they had a shorter duration of their illness and a lower prevalence of comorbidity on average than the respondents who were fully work-disabled. Both groups were heterogeneous with respect to type of chronic illness, with the most prevalent diseases being asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and musculoskeletal diseases.

Table 1.

Comparison of employed and fully work-disabled groups on socio-demographic characteristics

| Employed | Fully work-disabled | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 168 | 48.7 | 66 | 38.7 | 0.02 |

| Female | 177 | 51.3 | 104 | 61.3 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 44.2 (10.2) | 52.4 (8.6) | <0.001 | ||

| Educational level | |||||

| Low | 127 | 39.0 | 115 | 71.9 | <0.001 |

| Middle | 99 | 30.4 | 32 | 20.2 | |

| High | 99 | 30.6 | 12 | 7.8 | |

| Illness characteristics | |||||

| Duration (in years) since diagnosis, mean (SD) | 8.3 (8.8) | 10.3 (11.0) | 0.02 | ||

| Presence of comorbidity (%) | 54 | 15.7 | 49 | 28.7 | 0.001 |

| Work characteristics | |||||

| Hours of work/week, mean (SD) | 35 (11) | ||||

The medical health status of the employed patients was assessed by the GP as less life-threatening, less progressive, more changing in course, and more controllable by medical care compared to patients in the fully work-disabled group. The employed group experienced less functional limitations, less fatigue, and less pain compared to those who were fully work-disabled. The individuals in the employed group had more positively oriented illness perceptions compared to those who were fully work-disabled. In addition, those employed reported less psychological attributions regarding the cause of their illness (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medical health status, perceived health, illness perceptions, and employment status

| Employed | Fully work-disabled | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical health statusa | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

| Life-threatening | 1–3 | 1.14 | 0.39 | 1.35 | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Progressive deterioration | 1–3 | 1.40 | 0.64 | 1.77 | 0.73 | <0.001 |

| Changing in course | 1–3 | 1.99 | 0.85 | 1.81 | 0.79 | 0.017 |

| Controllability by medical care | 1–3 | 2.20 | 0.79 | 2.05 | 0.76 | 0.029 |

| Self-reported health | N | % | N | % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional limitations | ||||||

| None | 218 | 64.04 | 18 | 12.21 | <0.001 | |

| Light | 79 | 23.12 | 24 | 16.67 | ||

| Moderate | 35 | 10.30 | 56 | 39.16 | ||

| Severe | 9 | 2.54 | 46 | 31.96 | ||

| Self-reported health | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatiguea | 1–3 | 1.94 | 0.71 | 2.65 | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Paina | 1–3 | 1.55 | 0.71 | 2.38 | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Illness perceptionsa | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consequences | 1–5 | 2.53 | 0.80 | 3.68 | 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Chronic timeline | 1–5 | 4.27 | 0.76 | 4.43 | 0.62 | 0.027 |

| Cyclical timeline | 1–5 | 3.06 | 0.95 | 3.40 | 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Treatment control | 1–5 | 3.18 | 0.66 | 2.58 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Personal control | 1–5 | 3.20 | 0.78 | 2.83 | 0.81 | <0.001 |

| Coherence | 1–5 | 4.00 | 0.75 | 3.64 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

| Causal dimensions | ||||||

| Psychological attributions | 1–5 | 1.97 | 0.82 | 2.22 | 0.92 | 0.004 |

| Risk factors | 1–5 | 1.98 | 0.70 | 2.00 | 0.66 | 0.851 |

| Immunity | 1–5 | 2.10 | 0.87 | 2.18 | 0.84 | 0.365 |

aA higher score implies more life threatening, more progressive deterioration, more changing course, better controllability, more fatigue, more pain, more severe consequences, more chronic timeline, more cyclical timeline, more treatment control, more personal control, more coherence (better understanding of the disease), and more causal attributions

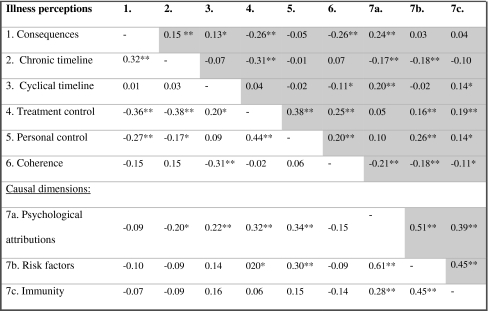

The correlation matrix presented in Table 3 shows that the different dimensions of illness perceptions correlate in a logical way. The different concepts of the illness perceptions correlate significantly in the employed as well as in the work-disabled group. Although the mean scores are different in both groups, the illness perceptions are a coherent group in the work-disabled, as well as in the employed patients.

Table 3.

Correlations of the illness perceptions, within both groups

* P < 0.01; ** P < 0.01; Shaded: employment; regular: complete work-disability

The results of logistic regression show that the socio-demographic characteristics together with the medical health status judged by the GP account for 38.2% of the variance in employment status (Table 4, second column). A higher age, being female, a lower level of education, and the judgment of the GP that the health status of the patients is progressive were all significantly associated with work disability.

Table 4.

Multivariate comparisons between employment and full work disability

| Fully work-disabled (reference: employed) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Block 1 + 2 | Model 2: Block 1 + 2 + 3 | Model 3: Block 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 | |

| R 2 = 38.2% | R 2 = 65.4%a | R 2 = 77.4%a | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| 1a. Socio-demographic characteristics | |||

| Age | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | 1.08 (1.01–1.14) |

| Female (reference: male) | 3.33 (1.98–5.59) | 3.00 (1.33–6.80) | 5.33 (1.64–17.36) |

| Level of education (reference: low) | |||

| Middle | 0.57 (0.32–1.02) | 0.45 (0.18–1.10) | 0.32 (0.09–1.15) |

| High | 0.20 (0.10–0.42) | 0.21 (0.07–0.57) | 0.20 (0.05–0.79) |

| 1b. Illness characteristics | |||

| Time since diagnosis | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 0.98 (0.91–1.05) |

| Presence of comorbidity (reference: absence) | 1.70 (0.96–3.01) | 2.04 (0.86–4.85) | 3.45 (0.98–12.14) |

| 2. Medical health status | |||

| Life-threatening | 1.62 (0.84–3.11) | 3.09 (1.00–9.53) | 2.80 (0.54–14.60) |

| Progressive deterioration | 2.80 (1.68–4.69) | 1.67 (0.77–3.64) | 2.48 (0.85–7.25) |

| Changing course | 0.78 (0.48–1.28) | 1.13 (0.52–2.43) | 1.07 (0.33–3.41) |

| Controllability by medical care | 0.70 (0.42–1.15) | 0.86 (0.38–1.91) | 0.80 (0.24–2.61) |

| 3. Self-reported health | |||

| Functional limitations (reference: none) | |||

| Light | 3.15 (1.09–9.06) | 4.31 (0.93–19.87) | |

| Moderate | 11.94 (4.06–35.10) | 14.27 (2.90–70.23) | |

| Severe | 49.47 (11.55–211.87) | 21.92 (2.78–172.61) | |

| Fatigue | 2.42 (1.11–5.29) | 1.65 (0.56–4.87) | |

| Pain | 1.56 (0.66–3.70) | 1.79 (0.55–5.79) | |

| 4. Illness perceptions | |||

| Consequences | 5.34 (2.31–12.34) | ||

| Chronic timeline | 0.76 (0.29–2.03) | ||

| Cyclical timeline | 1.19 (0.62–2.26) | ||

| Treatment control | 0.48 (0.20–1.17) | ||

| Personal control | 0.91 (0.42–1.99) | ||

| Coherence | 1.38 (0.69–2.75) | ||

| Causal dimensions | |||

| Psychological attributions | 1.85 (0.91–3.77) | ||

| Risk factors | 0.98 (0.34–2.86) | ||

| Immunity | 1.05 (0.54–2.04) | ||

R 2 percentage of explained variance (Nagelkerke R 2), OR odd’s ratio, CI confidence interval of the odd’s ratio

aModel is significantly different from previous model (P < 0.001); bold type: P < 0.05

By adding self-reported health status to the model (Model 2, Table 4, third column), the percentage of explained variance of the total model increases to 65.4%. In this second model, functional limitations and fatigue were significantly associated with work disability. With the addition of the illness perceptions (Model 3, Table 4, fourth column), the percentage of explained variance increases to 77.4%. Complete work disability was associated with believing that the consequences of the illness are more severe. A higher age, being a woman, and a lower level of education were still associated with full work disability. Self-reported functional limitations were associated with work disability as well. Again, none of the medical health status variables appeared to be statistically significant in this final model.

Discussion

From our results it becomes clear that work disability is associated with a higher age, a lower level of education, and being female. In the Netherlands, more people with a higher age and more women than men are receiving work disability benefits (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek 1998; Van der Giezen et al. 1998). In people with a chronic illness, the chance to develop comorbidity increases with age (Wensing et al. 2001; van Manen et al. 2001). These associations were confirmed in the present study. In addition to these socio-demographic characteristics, self-reported health proved to be strongly associated with work disability, whereas medical health status, as assessed by the general practitioner, did not contribute to our model. Illness perceptions were significantly associated with work disability, in addition to self-reported health.

Illness perceptions and employment status

The present results confirm both hypotheses. Illness perceptions were significantly associated with work disability of the chronically ill. The addition of illness perceptions to our multivariate model increased the level of explained variance by almost 10%, from 65.4 to 77.4%. Previous research has shown that positive illness perceptions are associated with better outcomes (Petrie and Weinman 1997). Believing in changeable causes for illnesses or its limitations such as stress and overwork has been found to related to better adjustment and coping, and beliefs about disease course are potentially important predictors of self-management of chronic illness (Petrie and Weinman 1997).

In the present study, beliefs that the consequences of the disease were more serious were more prevalent in the work-disabled group. It can be hypothesized that patients who belief this may avoid situations in which they could experience limitations, leading to more sick leave from work, more problems regarding return to work following sick leave, and eventually, more work disability. This hypothesis is in line with experiences from multidisciplinary reintegration programs based on the ICF model (Koopman et al. 2004; Pfingsten et al. 1997). In these programs, it is acknowledged that sick leave and work disability are participation problems that are based on the limitations a patient experiences, as a result of impairments and disease, but also on external and personal factors like health beliefs, coping style and motivation. In these programs, attention is paid to invalidating cognitions and health beliefs to improve return to work.

Moreover, this finding supports earlier findings that the functional limitations the patient experiences as a result of the illness are stronger predictors of work status than the objective disease severity, as was shown in studies on patients with asthma (Boot 2004; Erickson and Kirking 2002; Blanc et al. 1996).

Methodological considerations

The present results provide information about associations between illness perceptions and employment status. Because of the cross-sectional design, cause and consequence cannot be distinguished.

Therefore, we cannot determine whether the negative illness cognitions are the antecedents of work disability, or are caused or aggravated by work disability. It should be investigated whether negative illness cognitions may be changed by interventions, and whether changes in illness cognitions contribute to the prevention or reduction of work disability. However, the present findings have provided valuable information about illness perceptions in relation to employment status, which provide directions for future studies with longitudinal designs.

We do not have information about the type of work the participants held nor the reason for work disability. Those employed may have found jobs in which they have sufficient job control opportunities, whereas those in the work-disabled group may not have succeeded in finding a work environment in which they are able to function with their chronic illness. An indication for this hypothesis is the difference in level of education.

The sample presented in this article can be considered representative for the population of the chronically ill in the Netherlands (Rijken et al. 2005). The employed patients differed considerably from the work-disabled patients with respect to age, sex, and level of education. We corrected our models for these variables, to make sure that the associations between the independent variables and work disability cannot be explained by these socio-demographic variables.

We have not investigated self-efficacy or perceived control. Self-efficacy is known to influence chronic disability (Marks et al. 2005a, b). It can be expected that self-efficacy will be an important determinant of sick leave and work disability as well.

Since the illness perceptions are added to the multivariate model that already contained self-perceived health, the percentage of explained variance only increases by the unique contribution of the illness perception as determinant of the differences between employed and work-disabled patients. The illness perceptions will also explain a part of the variance that is already explained by self-perceived health, because of covariance.

Implications

From the results of this study and previous research (Wijnhoven et al. 2001; Ferrucci et al. 2000; Moons et al. 2005), it can be recommended to give more attention to subjective health complaints and the illness perceptions of the patient. Subjective health and health beliefs seem to play an important role in sick leave and work disability. This is in line with the ICF-model and other health models, in which it is acknowledged that human functioning is influenced by different factors, such as personal factors. Prospective studies are needed, however, to confirm the role of subjective health and health beliefs and to explain the direction of the relationship between perceptions and beliefs and work status. Attention to incorrect illness perceptions of workers with a chronic illness may prevent functional limitations and sick leave. On the other hand, maintaining work may contribute to the feeling that it is possible to function well in spite of the disease, which may positively influence illness perceptions.

Conclusion

Illness perceptions are associated with employment status in the chronically ill. Chronically ill patients who are employed have more positive and less invalidating illness perceptions than those who are fully work-disabled. In addition, illness perceptions are significantly associated with work disability, even after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, medical health status, and self-reported health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Baanders AN, Rijken PM, Peters L. Labour participation of the chronically ill. A profile sketch. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:124–130. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc PD, Cisternas M, Smith S, Yelin EH. Asthma, employment status, and disability among adults treated by pulmonary and allergy specialists. Chest. 1996;109:688–696. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot CR (2004) Sick leave in asthma and COPD; the role of the disease, adaptation, work, psychosocial factors and knowledge. University of Nijmegen, Nijmegen

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (1998) Vademecum health statistics of the Netherlands. Staatsuitgeverij, ‘s-Gravenhage

- Cuelunaere B, Veerman TJ, Prins R, van der Giezen AM. In distant mirrors. Work incapacity and return to work. A study of low back pain patients in the Netherlands and five other countries. Zoetermeer: CTSV; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SR, Kirking DM. A cross-sectional analysis of work-related outcomes in adults with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88:292–300. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Baldasseroni S, Bandinelli S, de Alfieri W, Cartei A, Calvani D, Baldini A, Masotti G, Marchionni N. Disease severity and health-related quality of life across different chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1490–1495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A. Discovering statistics: using SPSS for windows. London: SAGE Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE, Glasgow RE, Zeiss AM. Personal models of osteoarthritis and their relation to self-management activities and quality of life. J Behav Med. 1994;17:143–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01858102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans M. Cognitive representations of chronic disease. An empirical study among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and Addinson’s disease. Utrecht: University of Utrecht; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans M, Foets M, Rijken M, Schreurs K, de Ridder D, Bensing J. Stress in chronic disease: do the perceptions of patients and their general practitioners match? Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6:229–242. doi: 10.1348/135910701169179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans M, Spreeuwenburg P, and Rijken PM (2005) Kerngegevens maatschappelijke situatie 2004. Patiëntenpanel Chronisch Zieken. Nivel – Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, Utrecht

- Heijmans MJ. Coping and adaptive outcome in chronic fatigue syndrome: importance of illness cognitions. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:39–51. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R, Clatworthy J, Polmear A, Weinman J. Do hypertensive patients’ beliefs about their illness and treatment influence medication adherence and quality of life? J Hum Hypertens. 2001;15:S65–S68. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman F, Edelaar M, Slikker R, Van der Woude L, Hoozemans M. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary occupational training program for chronic low back pain: a prospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:94–103. doi: 10.1097/01.PHM.0000107482.35803.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Benyamini Y, Brownlee S, Diefenbach M, Leventhal E, Patrick-Miller L, Robitaille C. Illness represntations: theoretical foundation. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman J, editors. Perceptions of health and illness: current research and applications. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DS. Illness representations and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1984. pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part I) Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:37–43. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II) Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:148–156. doi: 10.1177/1524839904266792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons P, Van Deyk K, De Geest S, Gewillig M, Budts W. Is the severity of congenital heart disease associated with the quality of life and perceived health of adult patients? Heart. 2005;91:1193–1198. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.042234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Morris R, Petrie KJ, Weinman J. Functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: do illness perceptions play a regulatory role? Br J Health Psychol. 1996;1:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R) Psychol Health. 2002;17:1–16. doi: 10.1080/08870440290001494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NCCZ (1995) Werk op maat: advies arbeidsmarktpositie van mensen met chronische gezondheidsproblemen (work in perspective: recommendations regarding the labour market position of people with chronic health problems). Zoetermeer, NCCZ

- Petrie KJ, Weinman J, Sharpe N, Buckley J. Role of patients’ view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. BMJ. 1996;312:1191–1194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie KJ, Weinman JA. Perceptions of health & illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pfingsten M, Hildebrandt J, Leibing E, Franz C, Saur P. Effectiveness of a multidmodal treatment program for chronic low-back pain. Pain. 1997;73:77–85. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimm TJ, Weinman J. Applying Leventhal’s self-regulation model to adaptation and intervention in rheumatic disease. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1998;5:62–75. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199806)5:2<62::AID-CPP155>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder R. Bringing back the body without the blame? The experience of ill and disabled people at work. Sociol Health Illness. 1995;17:605–631. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep10932129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rijken M, Van Kerkhof M, Dekker J, Schellevis FG. Comorbidity of chronic diseases: effects of disease pairs on physical and mental functioning. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0616-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Giezen AM, Cuelenaere B, Prins R (1998) Vrouwen vaker in de WAO? (work-incapacity in females). Bureau Astri, Leiden

- Van Manen JG, Bindels PJ, Ijzermans CJ, van der Zee JS, Bottema BJ, Schade E. Prevalence of comorbidity in patients with a chronic airway obstruction and controls over the age of 40. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:287–293. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC. Sociosomatics and illness in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:394–401. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensing M, Vingerhoets E, Grol R. Functional status, health problems, age and comorbidity in primary care patients. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:141–148. doi: 10.1023/A:1016705615207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven HA, Kriegsman DM, Hesselink AE, Penninx BW, de Haan M. Determinants of different dimensions of disease severity in asthma and COPD: pulmonary function and health-related quality of life. Chest. 2001;119:1034–1042. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]