Abstract

Glutamate receptors mediate neuronal intercommunication in the central nervous system by coupling extracellular neurotransmitter-receptor interactions to ion channel conductivity. To gain insight into structural and dynamical factors that underlie this coupling, solution NMR experiments were performed on the bi-lobed ligand-binding core of glutamate receptor 2 in complexes with a set of willardiine partial agonists. These agonists are valuable for studying structure-function relationships because their 5-position substituent size is correlated with ligand efficacy and extent of receptor desensitization whereas the substituent electronegativity is correlated with ligand potency. NMR results show that the protein backbone amide chemical shift deviations correlate mainly with efficacy and extent of desensitization. Pronounced deviations occur at specific residues in the ligand-binding site and in the two helical segments that join the lobes by a disulfide bond. Experiments detecting conformational exchange show that micro- to millisecond timescale motions also occur near the disulfide bond and vary largely with efficacy and extent of desensitization. These results thus identify regions displaying structural and dynamical dissimilarity arising from differences in ligand-protein interactions and lobe closure which may play a critical role in receptor response. Furthermore, measures of line broadening and conformational exchange for a portion of the ligand-binding site correlate with ligand EC50 data. These results do not have any correlate in the currently available crystal structures and thus provide a novel view of ligand-binding events that may be associated with agonist potency differences.

Keywords: Glutamate receptor, AMPA, partial agonists, NMR, chemical exchange

Introduction

Glutamate-activated cationic channels constitute one of the three superfamilies of ligand-gated receptors. Within this superfamily, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA)-selective receptors are the principal mediators of rapid neuronal excitation at central synapses and are associated with several higher-order neurological functions.1,2 Structurally, these receptors are tetrameric combinations3,4 of glutamate receptor subunits 1–4 (GluR1–4)5–8 arranged as dimers of dimers4,9 on post-synaptic neuronal plasma membranes. Each subunit consists of an extracellular N-terminal domain, an extracellular ligand-binding core, four membrane-associated regions (M1–M4), and an intracellular C-terminal segment.10–13 Biophysical studies of isolated “S1S2” ligand binding cores (Figure 1A)14–19 were initiated by the finding that the artificially linked S1 and S2 segments of GluR4 show pharmacological properties similar to those of the intact GluR4 receptor.20 Crystal structures of GluR2 S1S2 were subsequently determined in uncomplexed and several complexed states as well as in different dimeric configurations.21–31 These structures, when viewed alongside electrophysiological measurements of related receptors, have revealed the structural basis of various aspects of AMPA receptor function.

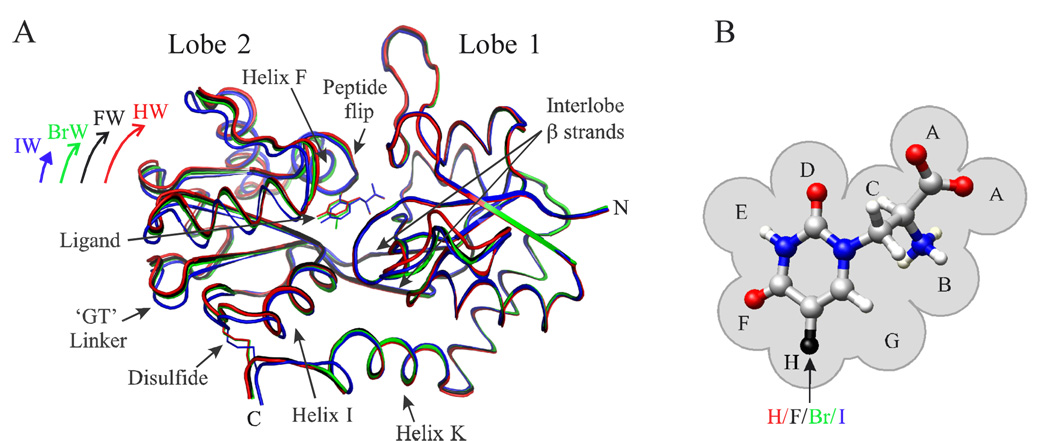

Figure 1.

(A) HW-, FW-, BrW-, and IW-S1S2 crystal structure traces (PDB IDs 1mqj, 1mqi, 1mqh, and 1mqg, respectively).27 (B) Willardiine compounds unsubstituted or halogenated at the 5-position. The letters (A–H) denote subsites of the ligand binding pocket as defined by Armstrong and Gouaux.22 The coloring scheme denoting the 5- position substituent is used throughout the paper (HW, red; FW, black; BrW, green; IW, blue).

Electrophysiological studies of the effects of unsubstituted and 5-substituted fluoro-, bromo-, and iodowillardiine partial agonists (HW, FW, BrW, and IW, respectively) on AMPA receptors have demonstrated that distinct current responses can be induced from a single atom change in the ligand, thus pointing to the usefulness of these willardiine derivatives for structure-function studies (Figure 1B).32–34,27 Substitution of hydrogen with more strongly electronegative halogens at the 5-position of the ring decreases the ligand pKa for deprotonation at the 3-position and increases ligand potency and binding affinity for AMPA receptors in the order HW < IW < BrW < FW.35,36,32–34,27 In contrast, the peak current and extent of receptor desensitization vary according to the size of the 5-position substituent as IW < BrW < FW < HW.32,33,27 Insights into the structural basis of the latter trend were gained from the determination of several crystal structures of S1S2 complexes with willardiine derivatives. A subset of these structures displays degrees of lobe closure which also vary with substituent size according to IW < BrW < FW < HW (Figure 1A), implying that the extent of lobe closure influences receptor response.27 However, the crystal structures do not provide an explanation for the correlation between ligand potency and 5-position electronegativity, suggesting that dynamics not evident in these structures may be important.

This is not meant to imply that the crystal structures are completely static. In fact, the structures of several S1S2-ligand complexes display global and/or local conformational variability. For example, IW-S1S2 protomers crystallized in the absence of zinc show differences in their degrees of lobe closure,27 and BrW- and IW-S1S2 in the absence of zinc show smaller extents of lobe closure relative to forms crystallized in the presence of zinc.27,28 In addition, several structures of S1S2 exhibit regions of local conformational variability, such as the “peptide flip segment” (Figure 1A). This region, which comprises residues D651–G653, forms part of the interface between the ligand and the second lobe of S1S2, and in some cases adopts conformations that promote interlobe mainchain hydrogen bonding.22,24,28 Conformational variability has also been observed in the ligand itself, as can be seen in the crystal structures of IW-S1S2.27 However, the structure of HW-S1S2, which displays the weakest affinity in the willardiine series, surprisingly shows no indication of conformational variability,27 though this might possibly be due to differences in crystallization conditions.

Since the extent to which these global and local structural differences depend on crystallization is unclear, we studied the backbone dynamics of the various willardiine-bound S1S2 systems in solution using NMR spectroscopy. Previous NMR backbone studies of GluR2 S1S2 examined the effects of full agonists and identified segments of the protein undergoing motions over a wide range of timescales.18,37,38 However, as these agonists produce similar degrees of lobe closure in the available crystal structures and similar extents of activation of the corresponding intact receptors, it has been difficult to relate variations in NMR, crystallographic, and electrophysiological observables.

The present paper extends previous NMR studies by examining the backbone structural and dynamical differences occurring in S1S2 complexed with HW, FW, BrW, and IW by measurements of mainchain amide chemical shift deviations (δω) and chemical exchange rates (Rex). The δω between these complexes may identify regions of S1S2 experiencing structural and/or dynamical changes due to differential extents of lobe closure and interaction with ligand. On the other hand, chemical exchange dynamics arising from conformational transitions between two or more chemically unique sites on µs – ms timescales may identify segments of S1S2 involved in GluR2 functions operating over similar timescales.

Formally, chemical exchange timescales are defined by the conformational transition rates (kex) and the associated separation frequencies (Δω) between exchange sites; kex ≫ Δω, kex ≈ Δω, and kex ≪ Δω correspond to fast, intermediate, and slow exchange regimes, respectively.39 Empirical identification of slower exchange processes can often be visually inferred from spectral line shapes when multiple peaks are observed for a given nucleus. Exchange regimes of single peaks can be distinguished by comparing Rex measured with different magnetic fields (B0), since Rex is proportional to in the fast exchange limit and is independent of B0 in the slow limit.40–42 Furthermore, changes in line shape and relative peak intensities as a function of temperature (T) can provide additional insights since such variations may also suggest chemical exchange.43 All of these effects were exploited to characterize the dynamics occurring in S1S2.

Specifically, we detected 15N Rex differences in S1S2 by performing high field strength NMR measurements at B0 = 900MHz and utilizing a pulse sequence designed for identifying chemical exchange in high molecular weight proteins.44 This experiment has been used recently to estimate Rex differences in S1S2 bound to full agonists.38 Because some systematic error is introduced in this experiment by neglecting chemical shift anisotropy effects,45 we also performed an analysis of 1H/15N peak intensities and line shapes for a range of T to supplement the 15N Rex measurements. This analysis provided an independent measure of spin relaxation occurring on the chemical shift timescale that showed qualitative agreement with the Rex results for several sites.

Overall, backbone amide δω and measures of chemical exchange were found to display unique patterns of variation in different regions of S1S2, such as the ligand binding site and segments near the conserved disulfide bond. Some of these patterns show correlations with either efficacy and extent of desensitization or potency, and thus identify sites in S1S2 that are sensitive to the various functional outcomes displayed by GluR2.

Results

Chemical Shift Deviations

Approximately 97% of the protein backbone amide 1H and 15N chemical shifts of HW-, FW-, BrW-, and IW-bound S1S2 have been assigned.46 Choosing one complex as reference, δω for those remaining were computed and mapped onto the associated crystal structures. Figures 2A and B reveal that, relative to HW-S1S2, the vast majority of 1H/15N δω vary more with ligand 5-position substituent size than electronegativity. This trend is evident in Figure 2B, which shows average δω values, denoted 〈δω〉. Specifically, relative to HW-S1S2, 〈δω〉 increases in the order FW- < BrW- < IW-S1S2, while relative to IW-S1S2, 〈δω〉 varies as BrW- < HW- ≈ FW-S1S2, with FW- slightly more divergent than HW-S1S2. Relative to HW-S1S2, the 〈δω〉 are correlated with GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization (Figure 2C). These correlations are akin to those described previously for extent of lobe closure and functional data.27

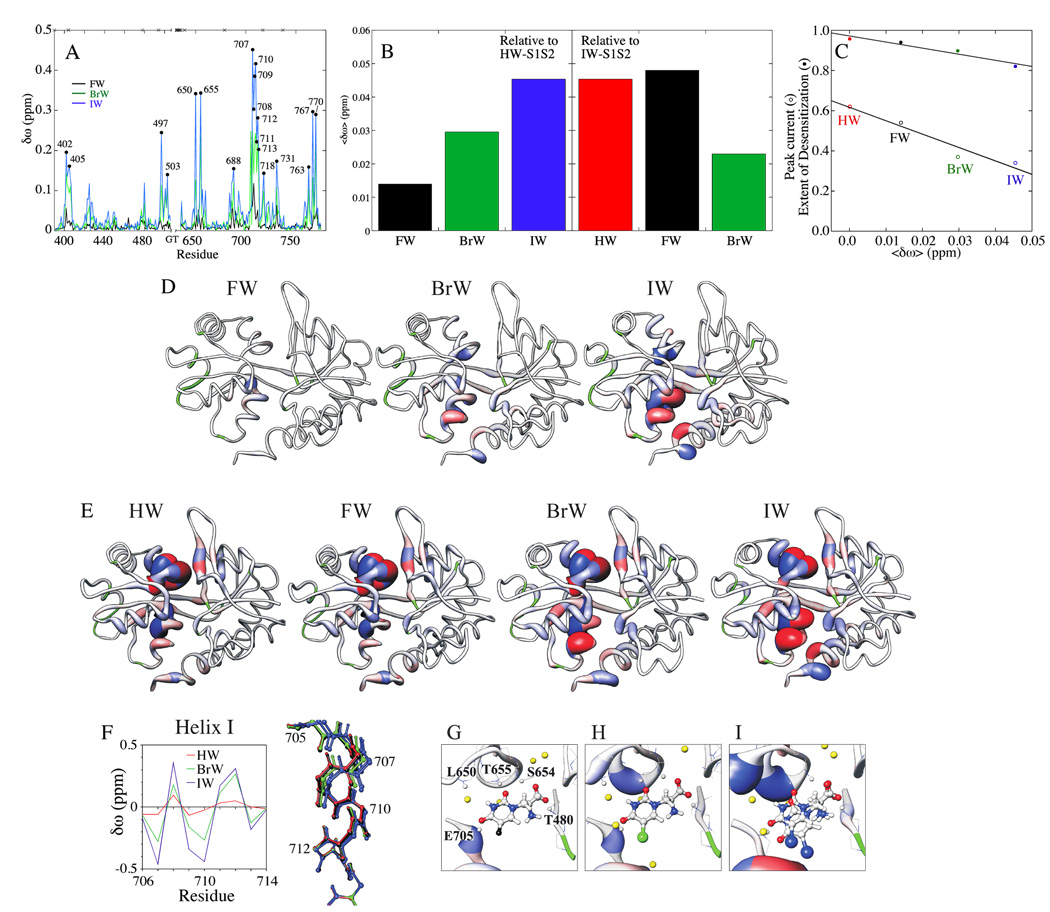

Figure 2.

S1S2 backbone δω. (A) , where δωH,ij and δωN,ij are the differences between the amide 1H and 15N chemical shifts, respectively, of i = FW-, BrW-, or IW-S1S2 and “reference” j = HW-S1S2. Sites having δω > 0.14 ppm for i = IW-S1S2 are labeled. The crosses indicate unassigned residues. (B) δω averaged over all assigned residues (<δω>), with either j = HW- (left) or IW-S1S2 (right). (C) Correlation of GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization with < δω >, using HW as the reference (HW is given <δω> = 0.0 in the plot). Peak current and extent of desensitization were taken from Jin et al.27 and were measured with an oocyte expression system in the presence and absence of cyclothiazide, respectively. (D) Mapping of δω = δωH,ij onto S1S2 crystal structures with j = HW-S1S2. Colors denote upfield (blue) and downfield (red) deviations. Both coil thickness and color intensity vary linearly with |δωH,ij|, with a maximum at 0.42 ppm. The green segments mark unassigned residues. (E) Same as (D) except j = glutamate-S1S2. Seven sites have |δωH,ij| > 0.42 ppm37,46 and are given the maximum width and color intensities for clarity. (F) Backbone amide 1H δω of sites in helix I, relative to FW-S1S2 (left); helix I crystal structures27 after backbone superimposition of E713–R715 (right). (G–I) Backbone amide 1H δω of binding site residues, relative to HW-S1S2, mapped onto (G) FW-, (H) BrW-, and (I) IWB-S1S2 crystal structures. Coil coloring and thickness are the same as in (D). Note the two orientations of the ligand in the IW-S1S2 structure. The yellow dots indicate the positions of water molecules.

Sites showing δω > 0.14 ppm are labeled in Figure 2A. Many of the large δω are found in helices I and K, which surround the disulfide bond (Figure 2D). Pronounced δω occur at T707-E713 in helix I and W767 and K770 at the base of helix K. The backbone amide 1H/15N of residues T707-E713, which exhibit the largest δω, form part of the hydrogen bonding network of helix I. Relative to HW-S1S2, the two sides of this helix experience either upfield or downfield amide 1H δω (Figure 2D). Figure 2F indicates that a periodic variation in the 1H δω occurs when FW-S1S2 is used as the reference, with the downfield shifts occurring on the side of the helix facing the lobe interface. Similar 1H δω trends are seen in helices I and K when glutamate-S1S2 is included in the analysis (Figure 2E). Specifically, the order of variation of most sites in these regions is FW- ≈ HW- < BrW- < IW-S1S2. Chemical shift changes are also associated with altered interlobe interactions, as can be seen with the indole 1H/15N of W767, which forms a hydrogen bond with the mainchain carbonyl of T707 in helix I (Figure 3A). The differences in the 1H/15N chemical shifts of this site (Figure 3B) reflect the 1H δω amplitude variation in helix I presented in Figure 2F. Furthermore, the base of helix K to which W767 is attached shows large 1H δω that vary mainly with ligand 5-position substituent size (Figures 2A, D, and E).

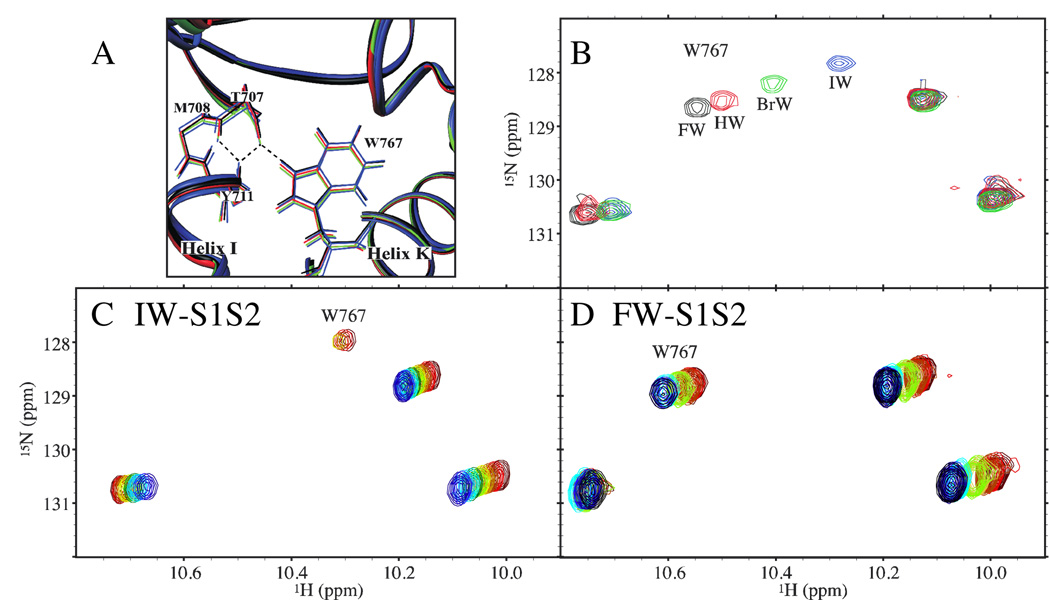

Figure 3.

(A) Putative hydrogen bond between the W767 indole 1H/15N and the T707 mainchain in the crystal structures.27 (B) 1H/15N HSQC spectra for T = 25°C showing the four W767 indole 1H/15N peaks for FW-, HW-, BrW-, and IW-S1S2. (C) and (D) 1H/15N HSQC spectra showing the variation with T of the four W767 indole 1H/15N peaks in IW- (C) and FW-S1S2 (D). The T ranges from 25°C (dark red) to 4°C (dark blue) for IW-S1S2 and from 25°C (dark red) to 2°C (black) for FW-S1S2.

Significant δω are also seen in residues L650 and T655, which are located at the two ends of the peptide flip segment (Figures 2G–I). These two sites, as well as T480, S654, and E705 are important due to their close proximity to the ligand. Except for L650, whose amide proton is separated from the ligand by a water molecule in the crystal structures, all of these residues make direct hydrogen bonds to ligand oxygen atoms.27 Whereas small 1H δω occur at T480 and S654, which interact with the ligand α- substituents, those at the remaining sites, which contact the γ-substituents, are more significant. Specifically, the 1H δω of L650 and T655 vary more with 5-position substituent size, whereas that of E705 group better as {HW, IW} and {FW, BrW}, which more closely reflects electronegativity and binding affinity27 differences.

Other sites showing more moderate δω in Figures 2A and D include S497 and G731, which are in the interlobe beta strands near to where S1S2 can make homodimer contacts,25,47 and E402 and E688, which form part of the lobe-lobe interface.

Backbone dynamics

Backbone dynamics on the chemical shift timescale were detected using measurements of 15N Rex and variations in 1H/15N peak intensity as a function of T. Both measures include a combination of conformational exchange rate(s) (kex), relative populations of exchanging sites (pA, pB, etc), and chemical shift differences between exchanging sites (Δω) Nevertheless, both can identify sites on the protein backbone undergoing chemical exchange on the µs-ms timescale, which can result from motion in the backbone itself and/or from changes in the environment of the spin.

Measurements of Rex

Figure 4A shows the S1S2 backbone 15N Rex of HW-, FW-, BrW-, and IW-S1S2 for B0 = 900MHz and T = 25°C. Most of the detected exchange occurs in lobe 2, which is also observed for full agonists.18,38 Several stretches of exchanging sites are found near helices F, I, and K. For example, large Rex values are seen in and around the peptide flip region (e.g. D651), at K663, and in lobe 1 and 2 residues near the disulfide bond (e.g., D719 and K770). Other sites showing pronounced Rex include T457, E637, V683, K699, and G731. The presence of exchange at E637, K699, V723, and nearby residues means that µs-ms dynamics also occur in most of the segments on the side of S1S2 facing the linkers to the ion channel in intact GluR2. Sites such as G698 and those indicated with symbols in Figures 4D and E showed very weak peaks with complex line shapes and in some cases were not included in the analysis. In addition, peaks of the threonine linker residue and nearby sites were not found for assignment and analysis, implying that severe relaxation may also occur for one or more sites near the ‘GT’ insert.

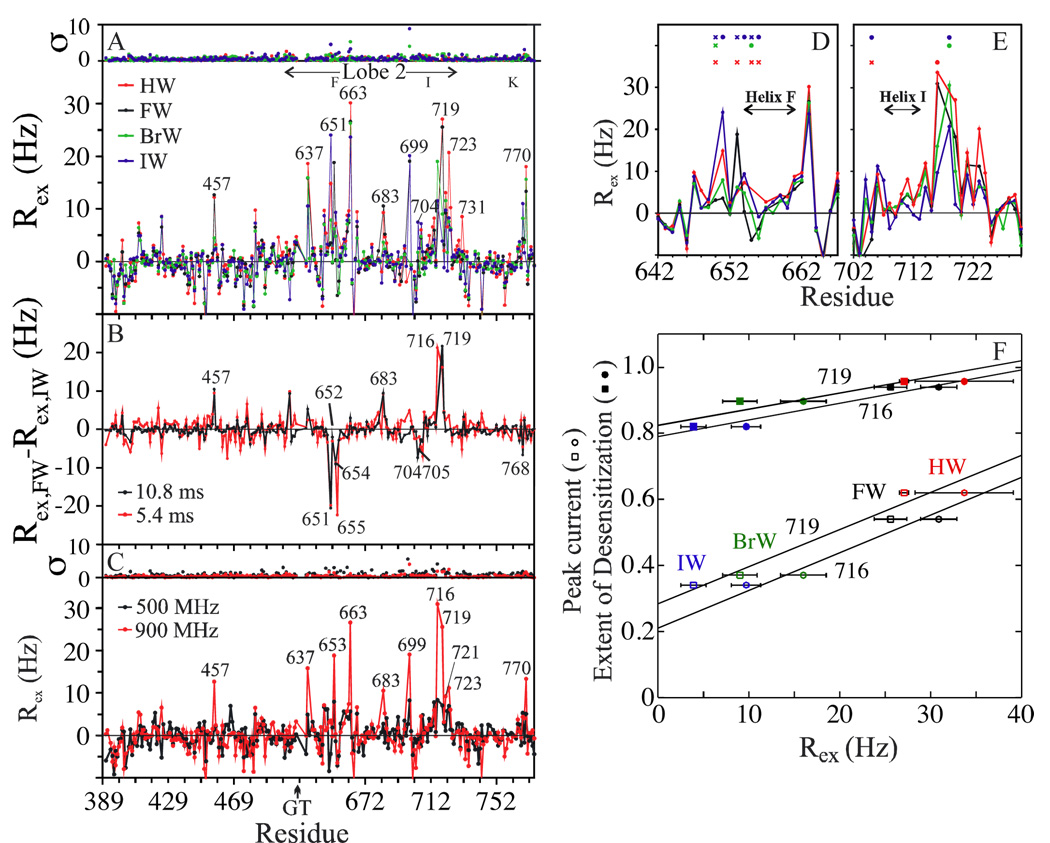

Figure 4.

S1S2 backbone 15N Rex at 25°C. (A) B0 = 900MHz and τ = 10.8ms, (B) Rex differences between FW- and IW-S1S2; B0 = 900MHz. (C) Rex for FW-S1S2 shown at two field strengths; τ = 16.2 and 10.8ms for the 500 and 900MHz data, respectively. (D), (E) Rex of sites near helices F and I; τ = 10.8 ms for (D) and 5.4 ms for (E). Dots above graphs specify sites analyzed despite showing very weak peaks. Crosses denote sites displaying very weak peaks often having complex line shapes which were not analyzed. (F) Correlation of Rex with GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization27 for K716 (τ = 5.4 ms) and D719 (τ = 10.8 ms). C718 was not analyzed for HW- and FW-S1S2 due to spectral overlap.

Figure 4B plots Rex deviations between FW- and IW-S1S2 and illustrates that several regions display marked differences. Overall, IW-S1S2 shows larger Rex values in the ligand binding site (e.g., T655 and E705) and at the base of helix K. On the other hand, FW-S1S2 shows increased Rex values at T457, V683, and sites in lobe 2 near the disulfide bond (e.g., K716 and D719). Figures 4E and F indicate that the Rex of K716 and D719 are positively correlated with GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization.

The Rex reported in Figure 4 correspond to the analysis of single peaks in the NMR spectra. With this experiment, we cannot identify sites associated with additional peaks which have undetectable intensities and/or cannot be distinguished due to spectral overlap. However, results for FW-S1S2 in Figure 4C suggest that some of the sites for which large Rex have been reported above may be associated with faster exchange regimes (kex > Δω) since their Rex are sensitive to increases in field strength (an approximately three-fold increase in rate is expected when changing from a 500 to 900MHz external field for fast exchange processes). For example, the estimated chemical exchange timescales (α) of K716 and D719 are α716 = 2.0 ± 0.6 and α719 = 2.0 ± 0.4 ;0 ≤ α < 1, α ≈ 1, and 1 ≤ α < 2 correspond to slow, intermediate, and fast exchange, respectively, determined from α ≈[(B02 + B01)/(B02 − B01)]×[(Rex2 − Rex1)/(Rex2 + Rex1)].41 Thus, insofar as the changes in Rex for particular 15N nuclei as a function of ligand reflect variations in conformational dynamics as opposed to changes in Δω between exchanging sites, the larger Rex could reflect slower transition rates kex and/or increased equilibrium probabilities of less dominant states [in the fast exchange limit, Rex = pApB(Δω)2/kex for two site exchange41].

1H/15N HSQC peak intensities as a function of T

Trends qualitatively similar to those in Figure 4 are observed from backbone amide 1H/15N inverse peak intensities Î (see Materials and Methods), increases in which suggest line broadening (or possibly decreases in site occupation). Figure 5A shows that the differences between Î for FW- and IW-S1S2 at 25, 20, and 14°C display trends similar to those obtained for Rex differences in Figure 4B. Figure 5C maps Î (14°C) onto crystal structures to illustrate regions showing large decreases in peak intensity; namely, the segment containing the peptide flip residues in IW- and HW-S1S2, the lobe 2 side of the disulfide bond in FW- and HW-S1S2, and the lobe 1 side of this bond in IW-S1S2.

Figure 5.

Backbone amide 1H/15N HSQC Î results. (A) Differences between Î of FW-and IW-S1S2 for commonly analyzed residues. (B) Correlation between Î (25°C) and EC50 measured in oocytes27 for each willardiine derivative. (C) Î (14°C) mapped onto crystal structure traces. Both coil thickness and color intensity vary with Î between Î ≤ 1 (white) and 11.1 (red). Unassigned (unanalyzed) sites are colored green (black). Sites not analyzed due to very weak peak intensities are given the maximum thickness and color.

In all systems, reduced peak intensities are evident at the peptide flip residue G653. For FW-S1S2, the resonances of other sites in and around the peptide flip region show strong single peaks and do not exhibit large increases in Î upon cooling from 25 to 14°C (Figures 5A and C). In contrast, several of these peaks in IW- and HW-S1S2 show severe intensity decreases for decreasing T, in agreement with the Rex results. The weakest peaks in this region occur for HW- and IW-S1S2 at L650 and T655, whose amide protons interface with the ligand. In fact, the peaks of these two sites could not be observed in many experiments involving HW-S1S2. Although these peaks are highly relaxed and exhibited complex line shapes for HW- and IW-S1S2, Figure 5B shows that their Î (25°C) are positively correlated with the EC50 values27 of these ligands. Interestingly, S652, which resides at the center of the peptide flip segment, shows neither significant Î (25°C) (Figure 5B) nor Rex (Figures 4A, B, and D) for any of the ligands.

Of the four tryptophan indole 1H/15N peaks in S1S2, only that for W767 shows significant changes in intensity as a function of ligand (Figures 3C and D). This amide group is of interest as it forms a hydrogen bond across the lobe interface between helices I and K. Whereas the peak in the FW-bound form remains relatively unbroadened for T between 2 and 25°C (Figure 3D), the peak in the IW-bound form broadens drastically with decreasing T (Figure 3C). The HW- and BrW-bound forms show intermediate results (not shown).

Discussion

The various full and partial agonists as well as antagonists have provided a useful tool for relating the structural and dynamic properties of the glutamate receptor S1S2 domain to functional properties that can only be measured for the intact protein. The series of willardiines considered in the present study are particularly suited for such an analysis because they differ structurally in only one position and have functional properties that vary according to the electronegativity (potency and binding affinity) and size (efficacy and desensitization) of the differing site.32–34 Using these ligands, we have identified NMR correlates of GluR2 functions from chemical shift and chemical exchange measurements for backbone amide nuclei of GluR2 S1S2. In particular, we have shown that average 1H/15N δω relative to HW-S1S2 as well as measures of conformational exchange for specific residues near the disulfide bond correlate with GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization. In contrast, similar measures of exchange for particular residues in the binding site correlate with ligand potency.

Helices I and K, the disulfide bond, and the interlobe linker

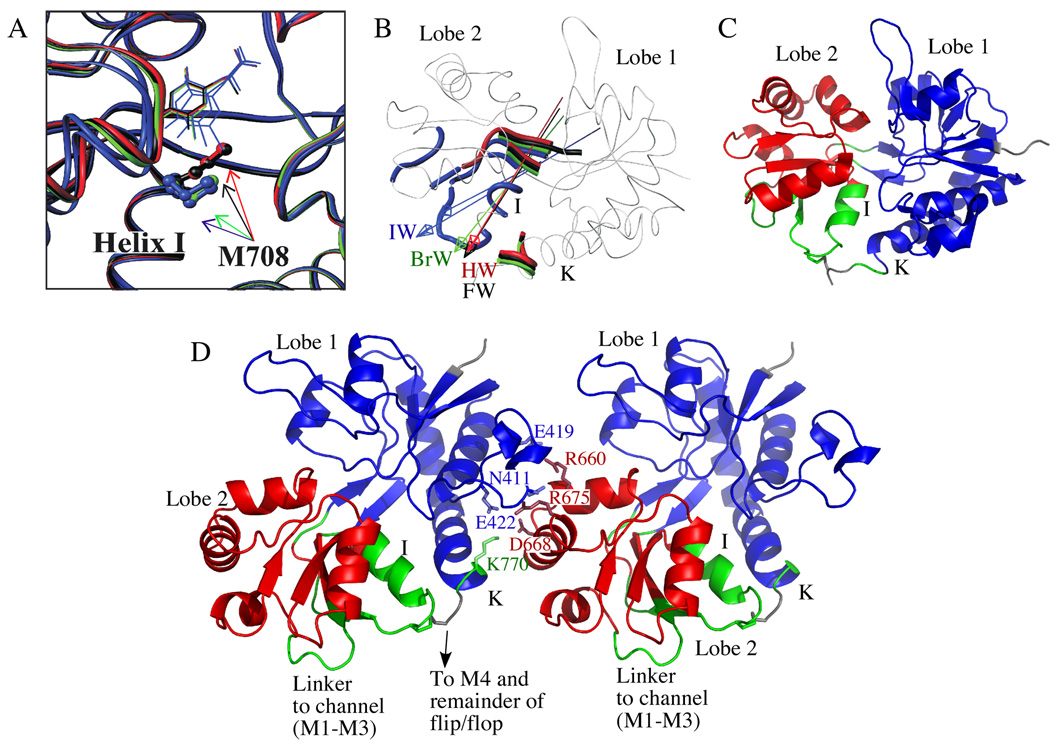

A number of interesting changes in chemical shift and dynamics occur in the region of S1S2 including the disulfide bond and the associated helices I and K. Although the crystal structures show little difference in this region among the various structures, a simple rigid body model of lobe closure constructed using the computer program DynDom48,49 suggests that this is the hinge region (Figure 6B). These hinge axes represent interlobe screw axes that bring about lobe closure from the apoA state of S1S222 to the various willardiine bound states27 using a combination of rotational and translational displacements. Figure 6B shows the calculated hinge axes for the various complexes and colors the “bending regions,” which include the sites at the interdomain boundaries and sites with outlying rotation vector components.48,49 DynDom defines the moving domains from a cluster analysis of rotation vectors of main-chain segments. Notably, the calculated sizes of the second domain for FW-, HW-, BrW- and IWA-S1S2 are 110, 109, 108, 95 residues, respectively. Thus, DynDom predicts differing domain sizes undergoing unique closure trajectories involving distinct hinge axes and bending regions. The difference between IW-S1S2 and the complexes with the other three willardiines is largely the inclusion of the C-terminal portion of helix I and the following loop as part of the first domain, which comprises most of lobe 1 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) M708 sidechain in HW-, FW-, BrW-, IWA-, and IWB-S1S2 crystal structures.27 (B) Putative hinge axes (arrows) and bending regions (colored segments) associated with S1S2 binding to HW, FW, BrW, or IW (protomers A and B shown) from the apoA state, computed using the program DynDom.48,49 (C) Ribbon representation of the IW-S1S2 crystal structure colored according to the domains defined by DynDom. The blue and red residues constitute the first and second (moving) domains, respectively, for all four compounds. The green residues are those that reside in moving domain 1 or 2, or in neither, depending on the willardiine derivative (see text). (D) The crystal structure (1lbb) of the putative lateral dimer and the residues that may be involved in forming the interface.25 The coloring is the same as (C).

The differences predicted from this simple rigid body model seem to be detected, to a degree, by the NMR spectra of sites near the hinge axes, including helix I, the base of helix K, and the interlobe strands. All of these regions show significant δω (Figure 2D). Figure 2F shows that the 1H δω relative to FW-S1S2 display a periodicity in helix I with an amplitude that varies as FW- ≈ HW- < BrW- < IW-S1S2. Periodicities in amide 1H chemical shifts relative to random coil values have been found in helices for a wide range of proteins and may be associated with helical distortions.50–53 Although amide 1H chemical shift variations can arise from a variety of factors (e.g., magnetic anisotropies, electric field effects,etc.54), correlations between the hydrogen bond length and chemical shift have been proposed, where downfield shifts are associated with shorter Hbonds. 55,56,54 Likewise, Figure 2F shows that helix I in the S1S2 crystal structures displays a bending-like distortion over the willariine series, with HW- and IW-S1S2 appearing most dissimilar. Consistent with the relation noted above, H-bonds that appear to be shorter in the IW-bound form relative to the HW form are downfield shifted. Although the global structural implications of these distortion differences are difficult to assess, when the crystal structures are viewed from the perspective of helix I, they are associated with differential displacements of the loop C-terminal to helix I, with larger displacements for the stronger partial agonists (but it is noted that the IWA- and IWBS1S2 structures crystallized in the absence of zinc show variability). Such displacements may be important because this loop is hydrogen bonded to the strand connected to the ion channel; e.g., the backbone carbonyl of D719 is hydrogen bonded to K506, which is immediately adjacent to the ‘GT’ insert.

Accompanying the backbone displacements observed in this region are clear deviations in chemical exchange. For example, Rex values for K716 and D719, which surround the disulfide bonded C718, correlate with the GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization (Figure 4F). Interestingly, differences in Rex have also been observed near C718 for the full agonists glutamate, AMPA, and quisqualate,38 and the disulfide bond has been shown to influence the energetics of ligand binding in glutamate receptors.57,58 The correlations in Figure 4F may reflect variations in the transition times and/or populations of functionally significant conformations on the µ-ms timescale. Measures of chemical exchange also show µs-ms motional differences for sites (particularly K770) at the base of helix K, which are linked to the segment containing K716 and D719 via the disulfide bond. Based on changes in peak intensity with T, this is more pronounced with IW than FW or HW (Figures 5A and C). Glutamate-S1S2 shows insignificant chemical exchange at this position,38 whereas increased chemical exchange is observed for kainate-S1S2 (MK Fenwick and RE Oswald, unpublished data). Although K770 has not been linked directly to function, it forms part of the flip/flop segment connected to M4 and stabilizes a section of a lateral dimer interface in a tetrameric receptor model (Figure 6D).25 In the proposed model, K770 interacts across the lateral dimer interface with D668 in helix G. The segments of the protein joined via the disulfide bond may therefore be a significant link between the M1–M3 channel region and M4 as well as the interface to adjacent subunits. Changes in structural and/or motional properties across this bond due to variable extents of lobe closure or twist may thus be associated with differences in activation and desensitization of the ion channel.

The local effects at the base of helix K also appear to be related to the near linear change in the 1H and 15N chemical shifts observed for the indole 1H/15N of W767 (Figure 3B). These shift changes show a loose correlation with receptor activity, where the more upfield shifted peaks are associated with reduced efficacies and extents of desensitization. Although the position of this peak has a variety of locations for other agonists, it resides farther upfield for the antagonists CNQX, DNQX, and UBP277 (MK Fenwick and RE Oswald, unpublished data), which is consistent with this view.

In addition to these local effects, some insights into more global lobe motions in S1S2 may also be gleaned from the indole 1H/15N peak of W767, since this site appears to be a sensitive measure of the lobe-lobe interaction at this position. This peak broadens dramatically at low T in IW-S1S2 but far less so in FW-S1S2 (Figures 3C and D). Interestingly, previous 19F-NMR studies which measured line broadening as a function of T and the spin relaxation times of a 5-fluorotryptophan version of the protein reveal insignificant chemical exchange for this tryptophan for these two partial agonists.59 This suggests that the tryptophan itself may be moving with lobe 1 and can sense chemical exchange in the IW-bound form at the lobe-lobe interface near helix I via its indole 1H/15N. These dynamics may be associated with the larger-scale movement of the lobes observed in the various crystal structures of IW-S1S2.27

The degree to which the chemical shift changes in the indole 1H/15N of W767, as well as those observed for proximal sites in and near helices I and K, are related to the detected dynamics and protein activity remains unclear. Interestingly, NMR studies of other proteins have noted such relationships60,61 and point to a longstanding question for glutamate receptors: namely, do partial agonists stabilize unique conformations of S1S2 associated with intermediate receptor activity or instead shift the equilibrium between a limited number of conformations corresponding to active or nonactive states? Clearly, crystallographic studies provide support for the former view but have focused on a subset of static pictures of S1S2 and global structural changes. On the other hand, previous NMR studies of various agonists have indicated a variety of global and local motions on the µs-ms and faster timescales.18,38,59 The NMR data shown in Figure 2–Figure 5 highlight some of the local regions that may be sensitive to receptor functional differences for the willardiine bound systems. However, more detailed chemical exchange studies and experiments probing longer timescale motions will likely help to better resolve some of these important questions.

Ligand binding site and peptide flip region

Increased Rex and Î occur for the less potent agonists at the ligand-lobe 2 interface, e.g. at L650 – K656 and E705 (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5). Furthermore, the Î (25°C) for L650 and T655 are correlated with ligand potency (Figure 5B). Although a definitive account of the binding events underlying these trends cannot be deduced from the data, a few potential interpretations are briefly considered. Firstly, the Rex and Î data for the lobe 1 residue T480, which hydrogen bonds to the ligand (Figure 2G), do not indicate chemical exchange. Thus, the trends in dynamics observed at the ligand-lobe 2 interface do not seem to be tied to differences in on and off rates of the ligands.

Assuming that the ligands remain bound over the timescale of the NMR experiment, alternative interpretations might consider the forms of the bound ligand and the dynamics associated with each form. Since these ligands are weak acids having pKas that fall within the approximate range of 8–10,35,36,32 the protonated state dominates at pH 5 and would be expected to be the dominant bound form unless its binding affinity is several orders of magnitude lower than that of the conjugate base. Interestingly, Fourier transform infrared resonance spectroscopy measurements at pH 7.4 suggest that the bound form is protonated based on difference spectra for the ligand carbonyl vibrations (V. Jayaraman, personal communication).62,63 If this is the case for all the ligands examined in the present study, then the Rex and Î data may indicate that the willardiines bind stably to sites in lobe 1 on the NMR timescale but give rise to significant µs-ms timescale dynamics at the ligand-lobe 2 interface for the less potent forms.

A glimpse of the underlying events for IW-S1S2 may be given by the different ligand conformations seen in its crystal structures (Figure 2I).27 Consistently, the 1H/15N line shape of E705 for IW-S1S2, whose amide 1H hydrogen bonds to the ligand 4-position carbonyl, was found to split at lower T, indicative of multiple conformations on the NMR timescale. Such chemical exchange observed for the lower potency agonists may contribute to differences in lobe-lobe “locking” kinetics15 and may be associated with a more loosely bound ligand which would be more likely to dissociate in the event of a transiently opened exit pathway.

In contrast to the variations in dynamics measured in the different regions of S1S2, the backbone amide chemical shifts appear to be influenced mainly by the ligand 5-position substituent size rather than electronegativity, i.e., by steric interactions in the binding site. One potential determinant of these variations is M708.27,28 As shown in Figure 6A, its sidechain extends into the ligand site ‘G’ in HW- and FW-S1S2 (see Fig. 1B) but assumes very different structures in BrW- and IW-S1S2, presumably due to changes in halogen size.27,28 The differences in sidechain structure are also reflected in a 5ppm deviation in the M708 Cα chemical shift for these ligands.46 Based on the crystal structures, this difference appears to enable its Sδ atom to accept a hydrogen bond from the hydroxyl of Y405 in HW- and FW-S1S2,64 and results in a larger binding cavity in BrW- and IW-S1S2, making it sterically feasible for IW to adopt the multiple conformations seen in the crystal structures. However, the extent to which these structural variations influence lobe closure and receptor function are unclear since the M708 sidechain positioning does not seem to be linked in an obvious way to functional differences in general based on other crystal structure data, e.g., for AMPA and kainate bound GluR2 S1S2 systems.21,22 Thus, additional sites acting in combination with M708 likely influence the global and local motions underlying function.

Although there are likely to be several, the peptide flip region seems to be another important site. For example, in the AMPA, glutamate, and quisqualate bound forms of GluR2 S1S2, there is a greater tendency to form a mainchain interlobe hydrogen bond between the carbonyl of S652 and the amide of G451 relative to the various willardiine bound protomers.22,24 Accordingly, we have observed significant amide δω at these and nearby sites between the willardiine and glutamate systems (Figure 2E). In addition, the 15N of G653 (which is separated by one bond from the carbonyl of S652) undergoes chemical exchange (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Surprisingly, although large variations in Rex and Î in and near the peptide flip region as a function of ligand are observed, no such variations are seen for S652. One interpretation is that the 1H and 15N nuclei of this residue are locally stabilized in all four complexes over the NMR timescale, possibly by the interlobe hydrogen bond between the carbonyl of D651 and the amide group of Y450 discussed previously.59 Thus, the extent to which the structural and dynamical differences in these and other sites (like M708) are associated with variations in lobe closure and receptor response seems to be a key question that remains to be answered fully.

In summary, although assigning the electrophysiological functions of intact, membrane-bound, tetrameric GluR2 to changes in structure and dynamics of its soluble, monomeric S1S2 domain must be approached with caution, considerable insight has been gained from studies of willardiine derivatives bound to S1S2. Previous analysis of crystal structures showed that GluR2 peak current and extent of desensitization can be correlated to a single structural variable - the degree of lobe closure in S1S2.27 Building on these findings, the present study has identified residues in S1S2 located near the putative hinge axes for lobe closure that display chemical shift changes and/or chemical exchange rates that are correlated with the same functional properties. Additional measurements of chemical exchange revealed sites at the ligand-lobe 2 interface which experience µs-ms timescale motions that are sensitive to differences in ligand potency. These results set the stage for future studies to determine the role of the detected motions in the functioning receptor.

Materials and Methods

S1S2 consists of residues N392 - K506 and P632 - S775 of the full rat GluR2-flop subunit,1 a ‘GA’ segment at the N-terminus, and a ‘GT’ linker connecting K506 and P632.22 Poly-histidine-tagged S1S2 was over-expressed at 37°C as inclusion bodies in BL-21(DE3) E. coli, refolded, partially digested with trypsin for histidine-tag removal, and purified, essentially according to protocols described elsewhere.14,65,18 Typically, 1.25L of isotopically enriched, fully deuterated, vitamin supplemented, minimal media66 yielded 3–4 samples of 0.25 – 0.35 mM purified protein, as measured using UV absorbance at 280nm and assuming a molar absorption coefficient of 41,500 M−1cm−1.67 Nearly complete deuteration at non-labile positions was achieved by dissolving lyophilized media components in pure D2O and culturing with deuterated glucose. Exchange of deuterons for protons at labile sites occurred naturally after bacterial lysis in aqueous refolding and purification buffers. The NMR buffer containing S1S2 and ligand was an aqueous solution of 25mM sodium acetate, 25mM sodium chloride, 3mM sodium azide, 12% D2O, pH 5.0. Final concentrations of HW, FW, BrW, and IW were 12, 5, 2, and 2 mM, respectively.

NMR experiments were performed on Varian 500 and 900MHz spectrometers equipped with cryoprobes. S1S2 backbone 1H/15N assignments for the various complexes at 25°C were determined previously.46 The indole 1H/15N of W767 residues was assigned from 1H/15N NOESY-HSQC spectra. Chemical exchange experiments were conducted at 25°C and either 500 or 900MHz. 1H/15N HSQC experiments for measuring relative peak intensities and line shapes at 4°C ≤ T ≤ 25°C were carried out at 500MHz. In all cases, high-resolution spectra were obtained by achieving nearly complete deuteration at nonlabile protein sites and by using TROSY-based NMR pulse sequences.68,44 The 1H/15N HSQC experiments at 4–10°C were run long to resolve highly relaxed peaks; typically, two identical experiments were performed sequentially, each involving 2048 × 128 total points and 256 scans, and the resulting spectra were added. Spectra from all experiments were processed and analyzed using NMRPipe69 and Sparky.70 All 2D free induction decays were zero-filled and modified using Lorentzian-to-Gaussian apodization prior to Fourier transformation. Signal intensities for the computation of Rex were estimated from fitted peak volumes69 whereas those for the variable T HSQC experiments were obtained from peak heights.70

Rex were computed as Rex ≈ Czz ln ρzz + Cβ ln ρβ, where Czz = (2τ)−1, Cβ=(〈κ〉−1)(4τ)−1, ρzz = Izz / Iα, and ρβ = Iβ / Iα.44 The intensities Iα, Iβ, and Izz were generated from three 2D experiments, each duplicated, with all six experiments performed simultaneously (i.e., interleaved). Rex values were computed from intensity averages and standard deviations σ were calculated from intensity deviations and error propagation formulas. 〈κ〉 denotes the trimmed mean (i.e., of values within one standard deviation) of κ = 1 – 2 ln ρzz / ln ρβ. This simplification, which neglects chemical shift anisotropy variations, leads to fluctuations in Rex about zero which limit the maximum detectable Rex.45,44 The Rex results reported here correspond to relaxation delay times τ = 5.4, 10.8ms, or 16.2ms. In general, 10.8ms was found to be a good compromise at B0 = 900MHz between experiment time needed to observe highly relaxed peaks and Rex sensitivity. However, 5.4ms data was utilized when resonances (typically Iβ) relaxed into the noise for larger τ values.

1H/15N HSQC-TROSY experiments at 4°C ≤ T ≤ 25°C were performed for both line shape analysis and calculation of inverse peak heights Î = <I>/I. The individual peak heights (I) were scaled by the trimmed mean peak height over the backbone (<I>) to compare results for different spectra. One expects the peak heights of sites undergoing exchange to diminish more significantly with decreasing T than <I>, although such effects are clearly not limited to chemical exchange. In the limit of negligible intrinsic transverse relaxation from processes other than exchange, R2 = Rex, , and the inverse intensity at the peak maximum is 1/I(0) ∝ Rex. Thus, qualitative agreement between Î and Rex is anticipated, especially for TROSY68 spectra of perdeuterated S1S2, in which other contributions to spin relaxation are reduced.71

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eric Gouaux (Vollum Institute) for the S1S2 construct, Marco Tonelli and Klaas Hellenga (NMRFAM, Univ. of Wisconsin) for NMR assistance, Jim Kempf (RPI) for providing Varian pulse sequences for Rex experiments, David Jane (Univ. Bristol) for supplying bromowillardiine, and Vasanthi Jayaraman (Univ. Texas) for contributing FTIR data. M. Tonelli is especially thanked for helping adapt pulse sequences for use on a 900MHz spectrometer. M.K.F. and R.E.O. acknowledge, respectively, NIH grants T32CA09682 (Bendicht Pauli, P.I.) and GM068935. This study made use of the NMR Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grants P41RR02301 (BRTP/NCRR) and P41GM66326 (NIGMS), as well as by NIH (RR02781, RR08438), the NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and the USDA.

Abbreviations

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid

- δω

chemical shift deviation(s)

- Rex

chemical exchange rate(s)

- GluR

glutamate receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned Glutamate Receptors. Annual Rev. Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharm. Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laube B, Kuhse J, Betz H. Evidence for a tetrameric structure of recombinant NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:2954–2961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02954.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenmund C, Stern-Bach Y, Stevens CF. The tetrameric structure of a glutamate receptor channel. Science. 1998;280:1596–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollmann M, O'sheagreenfield A, Rogers SW, Heinemann S. Cloning by Functional Expression of a Member of the Glutamate Receptor Family. Nature. 1989;342:643–648. doi: 10.1038/342643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulter J, Hollmann M, O'sheagreenfield A, Hartley M, Deneris E, Maron C, Heinemann S. Molecular-Cloning and Functional Expression of Glutamate Receptor Subunit Genes. Science. 1990;249:1033–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.2168579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keinanen K, Wisden W, Sommer B, Werner P, Herb A, Verdoorn TA, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. A Family of Ampa-Selective Glutamate Receptors. Science. 1990;249:556–560. doi: 10.1126/science.2166337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sommer B, Keinanen K, Verdoorn TA, Wisden W, Burnashev N, Herb A, Kohler M, Takagi T, Sakmann B, Seeburg PH. Flip and Flop - a Cell- Specific Functional Switch in Glutamate-Operated Channels of the Cns. Science. 1990;249:1580–1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1699275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safferling M, Tichelaar W, Kummerle G, Jouppila A, Kuusinen A, Keinanen K, Madden DR. First images of a glutamate receptor ion channel: Oligomeric state and molecular dimensions of GluRB homomers. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13948–13953. doi: 10.1021/bi011143g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollmann M, Maron C, Heinemann S. N-Glycosylation Site Tagging Suggests a 3-Transmembrane Domain Topology for the Glutamate-Receptor Glur1. Neuron. 1994;13:1331–1343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wo ZG, Oswald RE. Transmembrane topology of two kainate receptor subunits revealed by N-glycosylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7154–7158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett JA, Dingledine R. Topology Profile for a Glutamate-Receptor - 3 Transmembrane Domains and a Channel-Lining Reentrant Membrane Loop. Neuron. 1995;14:373–384. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wo ZG, Oswald RE. Unraveling the Modular Design of Glutamate-Gated Ion Channels. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen GQ, Gouaux E. Overexpression of a glutamate receptor (GluR2) ligand binding domain in Escherichia coli: Application of a novel protein folding screen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13431–13436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abele R, Keinanen K, Madden DR. Agonist-induced isomerization in a glutamate receptor ligand-binding domain - A kinetic and mutagenetic analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:21355–21363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909883199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayaraman V, Keesey R, Madden DR. Ligand-protein interactions in the glutamate receptor. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8693–8697. doi: 10.1021/bi000892f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madden DR, Abele R, Andersson A, Keinanen K. Large-scale expression and thermodynamic characterization of a glutamate receptor agonistbinding domain. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4281–4289. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2000.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFeeters RL, Oswald RE. Structural mobility of the extracellular ligand-binding core of an ionotropic glutamate receptor. Analysis of NMR relaxation dynamics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10472–10481. doi: 10.1021/bi026010p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramanoudjame G, Du M, Mankiewicz KA, Jayaraman V. Allosteric mechanism in AMPA receptors: A FRET-based investigation of conformational changes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10473–10478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603225103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuusinen A, Arvola M, Keinanen K. Molecular dissection of the agonist binding site of an AMPA receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:6327–6332. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen GQ, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate-receptor ligand-binding core in complex with kainate. Nature. 1998;395:913–917. doi: 10.1038/27692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-Sensitive glutamate receptor: Crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hogner A, Kastrup JS, Jin R, Liljefors T, Mayer ML, Egebjerg J, Larsen IK, Gouaux E. Structural basis for AMPA receptor activation and ligand selectivity: Crystal structures of five agonist complexes with the GluR2 ligand-binding core. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:93–109. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin R, Horning M, Mayer ML, Gouaux E. Mechanism of activation and selectivity in a ligand-gated ion channel: Structural and functional studies of GluR2 and quisqualate. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15635–15643. doi: 10.1021/bi020583k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun Y, Olson R, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E. Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong N, Mayer M, Gouaux E. Tuning activation of the AMPA-sensitive GluR2 ion channel by genetic adjustment of agonist-induced conformational changes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5736–5741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037393100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin R, Banke TG, Mayer ML, Traynelis SF, Gouaux E. Structural basis for partial agonist action at ionotropic glutamate receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:803–810. doi: 10.1038/nn1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin R, Gouaux E. Probing the function, conformational plasticity, and dimer-dimer contacts of the GluR2 ligand-binding core: Studies of 5-substituted willardiines and GluR2 S1S2 in the crystal. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5201–5213. doi: 10.1021/bi020632t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm MM, Naur P, Vestergaard B, Geballe MT, Gajhede M, Kastrup JS, Traynelis SF, Egebjerg J. A binding site tyrosine shapes desensitization kinetics and agonist potency at GluR2 - A mutagenic, kinetic, and crystallographic study. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35469–35476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robert A, Armstrong N, Gouaux JE, Howe JR. AMPA receptor binding cleft mutations that alter affinity, efficacy, and recovery from desensitization. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:3752–3762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0188-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong N, Jasti J, Beich-Frandsen M, Gouaux E. Measurement of conformational changes accompanying desensitization in an ionotropic glutamate receptor. Cell. 2006;127:85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patneau DK, Mayer ML, Jane DE, Watkins JC. Activation and Desensitization of AMPA Kainate Receptors by Novel Derivatives of Willardiine. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:595–606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00595.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong LA, Mayer ML, Jane DE, Watkins JC. Willardiines differentiate agonist binding-sites for kainate-preferring versus AMPA-preferring glutamate receptors in DRG-neurons and Hippocampal-neurons. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:3881–3897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03881.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jane DE, Hoo K, Kamboj R, Deverill M, Bleakman D, Mandelzys A. Synthesis of willardiine and 6-azawillardiine analogs: Pharmacological characterization on cloned homomeric human AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:3645–3650. doi: 10.1021/jm9702387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wempen I, Fox JJ. Spectrophotometric studies of nucleic acid derivatives & related compounds. 6. On the structure of certain 5- & 6-halogenouracils & -cytosines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:2474–2477. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lidak MY, Paegle RA, Stradyn YP, Dipan IV. Protolysis of Some alpha-amino-beta-(pyrimidyl-1) propionic acids and of their analogs. Khimiya Geterotsiklicheskikh Soedinenii. 1972:708–712. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McFeeters RL, Swapna GVT, Montelione GT, Oswald RE. Letter to the Editor: Semi-automated backbone resonance assignments of the extracellular ligand-binding domain of an ionotropic glutamate receptor. J. Biomol.NMR. 2002;22:297–298. doi: 10.1023/a:1014954931635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valentine ER, Palmer AG. Microsecond-to-millisecond conformational dynamics demarcate the GluR2 glutamate receptor bound to agonists glutamate, quisqualate, and AMPA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3410–3417. doi: 10.1021/bi047984f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer AG, Grey MJ, Wang C. Solution NMR spin relaxation methods for characterizing chemical exchange in high-molecular-weight systems. Methods Enzymol. 2005;394:430–465. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)94018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ishima R, Torchia DA. Estimating the time scale of chemical exchange of proteins from measurements of transverse relaxation rates in solution. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;14:369–372. doi: 10.1023/a:1008324025406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millet O, Loria JP, Kroenke CD, Pons M, Palmer AG. The static magnetic field dependence of chemical exchange linebroadening defines the NMR chemical shift time scale. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2867–2877. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer AG, Kroenke CD, Loria JP. Nuclear magnetic resonance methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Biological Macromolecules, Pt B. 2001;339:204–238. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mcconnell HM. Reaction Rates by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Chem.Phys. 1958;28:430–431. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C, Rance M, Palmer AG. Mapping chemical exchange in proteins with MW > 50 kD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:8968–8969. doi: 10.1021/ja035139z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C, Palmer AG. Solution NMR methods for quantitative identification of chemical exchange in N-15-labeled proteins. Mag. Res. Chem. 2003;41:866–876. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fenwick MK, Oswald RE. Backbone chemical shift assignment of a glutamate receptor ligand binding domain in complexes with five partial agonists. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2007;1:241–243. doi: 10.1007/s12104-007-9067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leever JD, Clark S, Weeks AM, Partin KM. Identification of a site in GluR1 and GluR2 that is important for modulation of deactivation and desensitization. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;64:5–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayward S, Berendsen HJC. Systematic analysis of domain motions in proteins from conformational change: New results on citrate synthase and T4 lysozyme. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 1998;30:144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayward S, Lee RA. Improvements in the analysis of domain motions in proteins from conformational change: DynDom version 1.50. Journal of Molecular Graphics & Modelling. 2002;21:181–183. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(02)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuntz ID, Kosen PA, Craig EC. Amide Chemical-Shifts in Many Helices in Peptides and Proteins Are Periodic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:1406–1408. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blanco FJ, Herranz J, Gonzalez C, Jimenez MA, Rico M, Santoro J, Nieto JL. NMR Chemical-Shifts - a Tool to Characterize Distortions of Peptide and Protein Helices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:9676–9677. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jimenez MA, Blanco FJ, Rico M, Santoro J, Herranz J, Nieto JL. Periodic Properties of Proton Conformational Shifts in Isolated Protein Helices - an Experimental-Study. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;207:39–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou NE, Zhu BY, Sykes BD, Hodges RS. Relationship between Amide Proton Chemical-Shifts and Hydrogen-Bonding in Amphipathic Alpha-Helical Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:4320–4326. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asakura T, Taoka K, Demura M, Williamson MP. The Relationship between Amide Proton Chemical-Shifts and Secondary Structure in Proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:227–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00197804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner G, Pardi A, Wuthrich K. Hydrogen-Bond Length and H-1-NMR Chemical-Shifts in Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:5948–5949. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. Relationship between Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance Chemical-Shift and Protein Secondary Structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutcliffe MJ, Wo ZG, Oswald RE. Three-dimensional models of non-NMDA glutamate receptors. Biophysical Journal. 1996;70:1575–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79724-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abele R, Lampinen M, Keinanen K, Madden DR. Disulfide bonding and cysteine accessibility in the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptor subunit GluRD - Implications for redox modulation of glutamate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25132–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.39.25132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ahmed AH, Loh AP, Jane DE, Oswald RE. Dynamics of the S1S2 glutamate binding domain of GluR2 measured using F-19 NMR spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:12773–12784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Volkman BF, Lipson D, Wemmer DE, Kern D. Two-state allosteric behavior in a single-domain signaling protein. Science. 2001;291:2429–2433. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mankiewicz KA, Rambhadran A, Du M, Ramanoudjame G, Jayaraman V. Role of the chemical interactions of the agonist in controlling alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor activation. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1343–1349. doi: 10.1021/bi062270l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mankiewicz KA, Rambhadran A, Wathen L, Jayaraman V. Chemical interplay in the mechanism of partial agonist activation in alpha-Amino-3-hydroxy- 5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors. Biochemistry. 2008;47:398–404. doi: 10.1021/bi702004b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gregoret LM, Rader SD, Fletterick RJ, Cohen FE. Hydrogen-Bonds Involving Sulfur-Atoms in Proteins. Proteins-Structure Function and Genetics. 1991;9:99–107. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen GQ, Sun Y, Jin R, Gouaux E. Probing the ligand binding domain of the GluR2 receptor by proteolysis and deletion mutagenesis defines domain boundaries and yields a crystallizable construct. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2623–2630. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pace CN, Vajdos F, Fee L, Grimsley G, Gray T. How to Measure and Predict the Molar Absorption-Coefficient of a Protein. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2411–2423. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T-2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRpipe - a Multidimensional Spectral Processing System Based on UNIX Pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California; [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishima R, Wingfield PT, Stahl SJ, Kaufman JD, Torchia DA. Using amide H-1 and N-15 transverse relaxation to detect millisecond time-scale motions in perdeuterated proteins: Application to HIV-1 protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10534–10542. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.