Abstract

Consensus does not exist on the level of arterial ligation in rectal cancer surgery. From oncologic considerations, many surgeons apply high tie arterial ligation (level of inferior mesenteric artery). Other strategies include ligation at the level of the superior rectal artery, just caudally to the origin of the left colic artery (low tie), and ligation at a level without any intraoperative definition of the inferior mesenteric or superior rectal arteries.

Publications concerning the level of ligation in rectal cancer surgery were systematically reviewed. Twenty-three articles that evaluated oncologic outcome (n = 14), anastomotic circulation (n = 5), autonomous innervation (n = 5), and tension on the anastomosis/anastomotic leakage (n = 2) matched our selection criteria and were systematically reviewed. There is insufficient evidence to support high tie as the technique of choice. Furthermore, high tie has been proven to decrease perfusion and innervation of the proximal limb. It is concluded that neither the high tie strategy nor the low tie strategy is evidence based and that low tie is anatomically less invasive with respect to circulation and autonomous innervation of the proximal limb of anastomosis. As a consequence, in rectal cancer surgery low tie should be the preferred method.

Key words: Total mesorectal excision, Rectal cancer, High tie, Low tie, Central arterial ligation, Inferior mesenteric artery

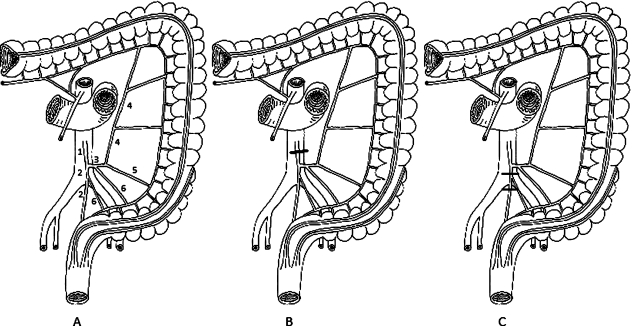

The most important prognostic factor for survival after rectal cancer surgery is represented by both distant metastasis and lymph node involvement. With respect to lymph node involvement, in 1908 Miles developed the abdominoperineal resection procedure for rectal cancer, incorporating transabdominal removal of lymphatic tissue. Believing that the route of lymphatic drainage of the rectum would follow its arterial supply, he recommended division of the superior rectal artery (SRA) just distally to the origin of the left colic artery (LCA; low tie; Fig. 1), with subsequent en bloc excision of nodes and bowel below.1 Within the same year Moynihan2 first proposed resection of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) at its origin (high tie; Fig. 1), including the apical group of lymph nodes within the resection. During subsequent years, the high tie principle was further advocated by several authors.3–7 However, according to the National Cancer Institute of the United States of America, an appropriate proximal lymphatic resection for rectal cancer without clinical evident lymph node disease is provided by the removal of the blood supply and lymphatics up to the level of the origin of the primary feeding vessel.8 For rectal cancer this is at the origin of SRA (low tie), which is immediately distal to the offspring of LCA. However, the key report on which this guideline is based is represented by the study by Rouffet et al.9 which is a trial on colon, not rectal, carcinoma. Actually, the level at which the artery is ligated in operations for rectal cancer varies greatly, depending largely on the surgeon.4,10–16 In daily practice only a minority of surgeons dissect the origin of LCA to estimate the level of arterial ligation with respect to IMA and SRA with certainty. Furthermore, in most publications on high tie and low tie, SRA is incorrectly denominated as IMA caudally to the origin of LCA. After Lanz and Wachsmut the artery caudally to the origin of LCA is denominated SRA and not IMA.17 Most authors use the term “high tie” for every type of ligation of IMA at all levels of the 1-cm to 7-cm long artery, including “flush” ligation of IMA at its very origin at the aorta.

Figure 1.

Anatomic graph of vascular ligation techniques A. Inferior mesenteric artery (1), superior rectal artery (2), left colic artery (3), ascending limb of the left colic artery (4), descending limb of the left colic artery (5), sigmoid arteries (6). B. High tie. C. Low tie, cranially or caudally to the origin of the sigmoid artery (if present), but always caudally to the origin of the left colic artery.

The choice of the level of arterial ligation in rectal cancer surgery can be based on three considerations: oncologic, anatomic, and technical. This article systematically reviews the evidence of possible benefits of high tie and low tie ligation techniques regarding these three different considerations.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed and Cochrane database. The following terms were used: high ligation, high tie, low tie, and low ligation. In addition the terms IMA, SRA, or LCA were used in combination with colorectal cancer, rectal cancer, lymph node, circulation, flow, stump pressure, function, autonomous, nerve, and tension. We also hand searched references.

The publication time window was from 1980 to 2007. Studies were included for this review if it concerned a randomized, controlled trial or a cohort study (prospective/retrospective) that evaluated adult patients who underwent rectal resection with high tie or low tie or an anatomic study, describing the location of the autonomous nerve supply in relation with ligation technique. Review articles, letters, comments, conference proceedings, and case reports were not selected for this review. With respect to oncologic considerations outcomes of interest were survival, disease recurrence, and incidence of positive lymph nodes at the root of IMA. With respect to anatomic considerations outcomes of interest for effect on anastomotic circulation were tissue blood flow, tissue oxygen tension, and anastomotic leakage, and for effect on autonomous innervation were bowel and urogenital dysfunction and location of nerve supply in relation with the root of IMA. With respect to technical considerations outcomes of interest were length of the proximal limb, tension on the anastomosis, and anastomotic leakage. An assessment of the quality of the included studies was conducted according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence.

Results

No randomized, clinical trials comparing high tie and low tie were found.

In total 23 studies were selected for the three categories as follows:

Oncologic considerations: studies that concerned the influence of the level of arterial ligation on cancer prognosis and/or the incidence of lymph node metastasis at the root of IMA. In total 14 studies were selected (Table 1): 7 studies that compared high tie and low tie13–16,18–20; and 7 noncomparative studies.21–27

- Anatomic considerations: studies that concerned the influence of the level of arterial ligation on anastomotic circulation (2A) and studies that concerned the influence of the level of arterial ligation on autonomous function (2B).

- 2A)

- 2B)

Technical considerations: studies that concerned the influence of the level of arterial ligation on the length of the proximal limb of anastomosis. In total two studies were found, which are mentioned in Table 1 (Corder et al.18 and Pezim and Nicholls14). Both studies compared anastomotic leakage rates between high tie and low tie and found no significant difference.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies concerning oncologic considerations of the level of arterial ligation

| Study | Level of evidence | Design | N | Tumor location | Procedure | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uehara et al. (2007)20 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 285 | Rectum | High or low tie | Five-year survival; incidence of LN+ | No significant difference;1.9% |

| Kanemitsu et al. (2006)24 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 1,188 | Colon and rectum | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 1.7% |

| Kawamura et al. (2005)25 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 121 | Rectosigmoid | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 0.0% (only pT1 tumors) |

| Fazio et al. (2004)19 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 458 | Rectum | High or low tie | Survival | No significant difference |

| Steup et al. (2002)27 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 605 | Rectum | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 0.3% |

| Kawamura et al. (2000)13 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 511 | Colon and rectum | High or low tie | Disease-free survival | No significant differencee |

| Hida et al. (1998)23 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 198 | Rectum | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 8.6% |

| Adachi et al. (1998)21 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 172 | Rectosigmoid | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 0.7% |

| Leggeri et al. (1994)26 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 252 | Rectum | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 4.0% |

| Corder et al. (1992)18 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 143 | Rectum | High or low tie | Survival; recurrence | No significant differences |

| Dworak et al. (1991)22 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 424 | Rectum | High tie | Incidence of LN+ | 1.0% |

| Surtees et al. (1990)16 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 250 | Rectum | High or low tie | Survival rate | No significant difference |

| Pezim and Nicholls (1984)14 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 1,370 | Rectosigmoid | High or low tie | Five-year survival | No significant difference |

LN+ = positive lymph node at the root of inferior mesenteric artery.

Table 2.

Overview of studies concerning the influence of the level of arterial ligation on anastomotic circulation

| Study | Level of evidence | Design | N | Procedure | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seike et al. (2007)31 | 2b | Prospective cohort | 96 | Rectal cancer resection with high tie | Tissue blood flow | Significant blood flow reduction after high techniques; high blood flow reduction in older, male patients |

| Dworkin et al. (1996)29 | 2b | Prospective cohort | 26 | Rectosigmoid resection | Tissue blood flow | Significant blood flow reduction after IMA ligation |

| Hall et al. (1995)28 | 2b | Prospective cohort | 62 | Colorectal resection with high or low tie | Tissue oxygen tension | No significant difference; tissue oxygen tension of sigmoid not adequate after both techniques |

| Kashiwagi et al. (1994)30 | 2b | Prospective cohort | 13 | IMA clamping | Tissue blood flow | No significant reduction |

| Corder et al. (1992)18 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 143 | Rectal resection with high or low tie | Anastomotic leakage rate | No significant differences |

IMA = inferior mesenteric artery.

Table 3.

Overview of studies concerning the influence of the level of arterial ligation on autonomous innervation

| Study | Level of evidence | Design | N | Procedure | Outcome measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liang et al. (2007)34 | 2b | Prospective cohort | 98 | D3-resection (high tie) | Urogenital function | 75.5% bladder and 91.7% sexual dysfunction |

| Sato et al. (2003)32 | 2b | Retrospective cohort | 132 | Rectal resection with high or low tie | Bowel function | High tie resulted in worse bowel function |

| Zhang et al. (2006)36 | 5 | Anatomic study | 16 | Exploration inferior mesenteric plexus in cadavers | Location inferior mesenteric plexus | Inferior mesenteric plexus was never located at the root of IMA |

| Nano et al. (2004)35 | 5 | Anatomic study | 42 | Exploration of left paraortic trunk in cadavers and patients undergoing rectal resection | Location left paraortic trunk | Left paraortic trunk was never located at the root of IMA |

| Hoer et al. (2000)33 | 5 | Anatomic study | 12 | Isolation of inferior mesenteric plexus in cadavers | Location inferior mesenteric plexus | Inferior mesenteric plexus is invariably located at the root of IMA |

IMA = inferior mesenteric artery.

Discussion

Oncologic Considerations

Lymph node involvement is a major prognostic factor for survival after rectal cancer surgery. The high tie technique includes the apical group of lymph nodes at the root of IMA within the resection. However, the incidence of metastatic lymph nodes at the origin of IMA has been reported to be relatively low in several studies, ranging from 0.3 to 8.6 percent.14,20,22,23,25–27 Furthermore, Kanemitsu et al.24 found no nodal metastases at the origin of IMA in patients with pT1 rectal tumors. This study suggested that low tie might be sufficient for pT1 sigmoid or rectal cancers. According to these findings, high tie might be beneficial only for patients with nodepositive disease. However, even in the case of nodepositive disease, it may be true that once the tumor has involved in these high lymph nodes, it has probably spread beyond. In this respect a factor could be represented by the generally poor prognosis of patients with rectal cancer with more than five involved lymph nodes who, if included in studies with high ligation, might obscure its value. Moreover, alternate lymphatic routes may frustrate attempts at tumor control by vascular ligation, regardless of the level of the tie. Tumors of the upper third of the rectum may drain along lymphatic channels that follow the portal vein and may be responsible for isolated lymphatic metastases within the hepatoduodenal ligament.37 In the lower third of the rectum, drainage may occur laterally to the iliac nodes via lymphatics within the lateral ligaments.38

Three retrospective cohort studies on high tie reported advantageous results with significant five-year and ten-year survival data for the very limited groups of patients with positive lymph nodes at IMA.23,24,26 We found the number of studies comparing high tie with low tie to be limited. All but one of these studies did not find any survival benefit after high tie in rectal cancer surgery.13–16,18–20 Only Slanetz and Grimson15 reported a stage-specific survival benefit of high tie in a retrospective study of 1,107 patients treated with high tie with extensive resection of mesenteric lymph drainage and 1,154 treated with low tie. However, this study did not eliminate the stage migration phenomenon, which may arise as a result of more accurate staging because of more extensive lymphadenectomy. Therefore, a proportion of patients might be assigned to a more advanced stage than would otherwise be the case, although their prognosis is the same. If this has occurred, the overall results in each stage would have improved and the proportion of patients in more advanced stages would have increased.39

Previous reports state that the number of harvested lymph nodes correlates significantly with long-term results in patients with colorectal carcinoma, advocating the importance of pathologic examination of 12 or more nodes.40,41 Limited lymph node dissection with preservation of IMA may result in a decreased number of harvested nodes. However, increasing the number of nodes by dissection of distant free nodes is considered to have no clinical impact.42

Most studies concerning high tie vs. low tie took place before the introduction of total mesorectal excision (TME) and neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer. Neoadjuvant treatment also has the potential to sterilize microscopic metastasis in nodes at the origin of IMA, undermining the rationale of high tie even more.43 On the other hand, preoperative radiotherapy did not seem to prevent distant metastasis in the Dutch TME trial.44 Possible benefit of high tie in combination with current surgical techniques and neoadjuvant treatment procedures needs to be investigated. In conclusion, assuming that reports on high tie procedures really reflect anatomically correct high tie dissections, there might be a small proportion of patients profiting from high tie. However, the amount and level of evidence for high tie is considered to be too modest for standardization of ligation of IMA.

Anatomic Considerations

Perfusion of the Proximal Limb of Anastomosis or Perfusion of Colostomy

Consensus exists on the necessity of well-perfused anastomotic limbs. However, factors jeopardizing anastomotic circulation are not well known.

The low tie technique allows for adequate blood supply to the colon proximally to the anastomosis, whereas after high tie vascularization of the distal colon and sigmoid depends completely on the middle colic and marginal arteries.23,35 The marginal artery arising from the middle colic artery is thought to be adequate for sustaining the viability of the remaining colon.45,46 However, despite most studies support this hypothesis, from preoperative measurements Dworkin et al. and Seike et al. concluded that high tie significantly reduces perfusion of the proximal limb.14,18,28,29,31 Furthermore, because in many patients a decrease in systemic blood pressure occurs during the recovery phase after surgery, it is not excluded that in some cases pressure in the marginal artery is insufficient to maintain adequate blood flow to the colon limb despite the inherent tendency of “auto-regulation” in its vascular bed.47 In correspondence with colon ischemia as a complication of IMA ligation in aorta surgery, especially in older patients with atherosclerotic vessels, ligation of IMA might result in hypoperfusion of the proximal limb.31,48 In addition, in some patients deficits of the marginal artery might exist at the splenic flexure.48 Kashiwagi et al.30 reported on the necessity of a larger sigmoid resection in rectal carcinoma surgery when IMA was ligated. Consequently, mobilization of the splenic flexure would always be necessary.

Despite evidence for a decreased perfusion of the proximal limb after high tie exists, it can be concluded that until now the benefit of low tie concerning perfusion of the anastomosis has not been proven but it might be present in patients with atherosclerotic disease.

Autonomous Innervation

Preservation of the autonomous nervous system is important to prevent urogenital and anorectal dysfunction.49 The paraortic trunks originate from the mesenteric plexus and descend along the aorta to join together and form the superior hypogastric plexus. If these are cut, ejaculation disorders and urinary incontinence may occur.50 Therefore, in high tie it is important to identify the safest point of ligation of IMA to avoid autonomous nerve damage during surgery of rectal cancer. In the literature, disagreement exists concerning the relationship between the origin and the course of IMA and the autonomous nerve supply. Two anatomic studies conclude that the origin of IMA is the only safe point of ligation, whereas another found that the inferior mesenteric plexus forms a dense network around IMA to a distance of 5 cm from the aorta, suggesting that high tie leads to damage of the sympathetic nerves.33,35,51 Two studies evaluated autonomic function after rectal resection. Liang et al.34 reported urogenital dysfunction in the majority of patients after high tie. Sato et al.32 compared patients who underwent rectal cancer resection before the implementation of low tie with patients who were treated after this implementation at the specific institution. Patients treated with high tie reported worse bowel function. Ligation of IMA at its origin disrupts the descending autonomic fibers and consequently leads to a long denervated colon segment, causing defecatory dysfunction.52 However, until now insufficient evidence exists about whether low tie has a better prognosis with regard to autonomic function.

Technical Considerations

Length of the Proximal Limb of Anastomosis

Apart from ischemia, tension on the anastomosis is thought to increase the risk of anastomotic leakage.23,35,53 Some authors state that high tie often is indispensable to guarantee a tension-free anastomosis in low anterior resection.35,53,54 With this technique the proximal limb is not withheld by an intact LCA-IMA-aorta axis.

However, a tension-free anastomosis also can be achieved in low tie resections by cutting the descending branch of LCA.18 To our knowledge, there are no studies that evaluate the effect of different ligation techniques on anastomotic tension. The aforementioned publications of Pezim and Nicholls14 and Corder et al.18 suggest that critical length of the proximal limb is not an issue in low tie strategy. In addition, splenic flexure mobilization is not indicated routinely.55

Conclusions

Since Miles and Moynihan respectively proposed low tie and high tie techniques for rectal carcinoma surgery in the same year (1908), until now the level of arterial ligation has been debated. The lack of prospective, randomized, clinical trials with sufficient follow-up in combination with an inconsistent methodology can be held responsible for this lack of consensus. In addition it is uncertain whether precise peroperative evaluation of anatomy has always been correct in the available studies that describe high tie and/or low tie ligation. High tie, because it has regained new interest in laparoscopy by its presumed advantage of easily creating mesenteric windows, is still advocated by many.51,54,56–59 However, from our review there is insufficient evidence to support high tie as the technique of choice. Although the anatomic disadvantage of high tie concerning impaired perfusion and innervation of the proximal colon limb has not been proven sufficiently with regard to anastomotic leakage and bowel dysfunction until now, low tie is anatomically less invasive and is preferable to high tie in rectal cancer surgery.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Miles WE. A method of performing abdomino-perineal excision for carcinoma of the rectum and of the terminal portion of the pelvic colon (1908) CA Cancer J Clin. 1971;21:361–364. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.21.6.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moynihan BG. The surgical treatment of cancer of the sigmoid flexure and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1908;463.

- 3.Ault GW, Castro AF, Smith RS. Clinical study of ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in left colon resections. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;94:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deddish MR. Abdominopelvic lymph node dissection in cancer of the rectum and distal colon. Cancer. 1951;4:1364–1366. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195111)4:6<1364::AID-CNCR2820040618>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91510-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosi PA, Cahill WJ, Carey J. A ten year study of hemicolectomy in the treatment of carcinoma of the left half of the colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1962;114:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.State D. Combined abdominoperineal excision of the rectum: a plan for standardization of the proximal extent of dissection. Surgery. 1951;30:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al. Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:583–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouffet F, Hay JM, Vacher B, et al. Curative resection for left colonic carcinoma: hemicolectomy vs. segmental colectomy. A prospective, controlled, multicenter trial. French Association for Surgical Research. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:651–659. doi: 10.1007/BF02054407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adachi Y, Kakisako K, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Miyahara M, Kitano S. Factors influencing bowel function after low anterior resection and sigmoid colectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:155–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bacon HE, Dirbas F, Myers TB, Ponce DL. Extensive lymphadenectomy and high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery for carcinoma of the left colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1958;1:457–464. doi: 10.1007/BF02633415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinnell RS. Results of ligation of inferior mesenteric artery at the aorta in resections of carcinoma of the descending and sigmoid colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:1031–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawamura YJ, Umetani N, Sunami E, Watanabe T, Masaki T, Muto T. Effect of high ligation on the long-term result of patients with operable colon cancer, particularly those with limited nodal involvement. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:803–807. doi: 10.1080/110241500447443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pezim ME, Nicholls RJ. Survival after high or low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during curative surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1984;200:729–733. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198412000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slanetz CA, Jr, Grimson R. Effect of high and intermediate ligation on survival and recurrence rates following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1205–1218. doi: 10.1007/BF02055167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surtees P, Ritchie JK, Phillips RK. High versus low ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1990;77:618–621. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loeweneck H, Feifel G. Lanz Wachsmuth Praktische Anatomie Bauch. Berlin: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corder AP, Karanjia ND, Williams JD, Heald RJ. Flush aortic tie versus selective preservation of the ascending left colic artery in low anterior resection for rectal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1992;79:680–682. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fazio S, Ciferri E, Giacchino P, et al. Cancer of the rectum: comparison of two different surgical approaches. Chir Ital. 2004;56:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uehara K, Yamamoto S, Fujita S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Impact of upward lymph node dissection on survival rates in advanced lower rectal carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2007;24:375–381. doi: 10.1159/000107779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adachi Y, Inomata M, Miyazaki N, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Distribution of lymph node metastasis and level of inferior mesenteric artery ligation in colorectal cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:179–182. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dworak O. Morphology of lymph nodes in the resected rectum of patients with rectal carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 1991;187:1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(11)81075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hida J, Yasutomi M, Maruyama T, et al. Indication for using high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in rectal cancer surgery. Examination of nodal metastases by the clearing method. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:984–987. doi: 10.1007/BF02237385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Komori K, Kato T. Survival benefit of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in sigmoid colon or rectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93:609–615. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamura YJ, Sakuragi M, Togashi K, Okada M, Nagai H, Konishi F. Distribution of lymph node metastasis in T1 sigmoid colon carcinoma: should we ligate the inferior mesenteric artery? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:858–861. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leggeri A, Roseano M, Balani A, Turoldo A. Lumboaortic and iliac lymphadenectomy: what is the role today? Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37(Suppl):S54–S61. doi: 10.1007/BF02048433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steup WH, Moriya Y, van de Velde CJ. Patterns of lymphatic spread in rectal cancer. A topographical analysis on lymph node metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:911–918. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall NR, Finan PJ, Stephenson BM, Lowndes RH, Young HL. High tie of the inferior mesenteric artery in distal colorectal resections: a safe vascular procedure. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:29–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00337583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dworkin MJ, Allen-Mersh TG. Effect of inferior mesenteric artery ligation on blood flow in the marginal artery-dependent sigmoid colon. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashiwagi H, Konishi F, Furuta K, Okada M, Saito Y, Kanazawa K. [Tissue blood flow of the sigmoid colon for safe anastomosis following ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery] Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1994;95:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seike K, Koda K, Saito N, et al. Laser Doppler assessment of the influence of division at the root of the inferior mesenteric artery on anastomotic blood flow in rectosigmoid cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:689–697. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sato K, Inomata M, Kakisako K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Kitano S. Surgical technique influences bowel function after low anterior resection and sigmoid colectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1381–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoer J, Roegels A, Prescher A, Klosterhalfen B, Tons C, Schumpelick V. [Preserving autonomic nerves in rectal surgery. Results of surgical preparation on human cadavers with fixed pelvic sections] Chirurg. 2000;71:1222–1229. doi: 10.1007/s001040051206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang JT, Huang KC, Lai HS, Lee PH, Sun CT. Oncologic results of laparoscopic D3 lymphadenectomy for male sigmoid and upper rectal cancer with clinically positive lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1980–1990. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nano M, Dal Corso H, Ferronato M, Solej M, Hornung JP, Dei PM. Ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery in the surgery of rectal cancer: anatomical considerations. Dig Surg. 2004;21:123–126. doi: 10.1159/000077347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang C, Li GX, Ding ZH, Wu T, Zhong SZ. [Preservation of the autonomic nerve in rectal cancer surgery: anatomical factors in ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery] Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006;26:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugarbaker PH. Metastatic inefficiency: the scientific basis for resection of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol Suppl. 1993;3:158–160. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930530541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauer I, Bacon HE. A new approach for excision of carcinoma of the lower portion of the rectum and anal canal. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1952;95:229–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feinstein AR, Sosin DM, Wells CK. The Will Rogers phenomenon. Stage migration and new diagnostic techniques as a source of misleading statistics for survival in cancer. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:1604–1608. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198506203122504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein NS, Sanford W, Coffey M, Layfield LJ. Lymph node recovery from colorectal resection specimens removed for adenocarcinoma. Trends over time and a recommendation for a minimum number of lymph nodes to be recovered. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106:209–216. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/106.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tepper JE, O’Connell MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Impact of number of nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:157–163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prandi M, Lionetto R, Bini A, et al. Prognostic evaluation of stage B colon cancer patients is improved by an adequate lymphadenectomy: results of a secondary analysis of a large scale adjuvant trial. Ann Surg. 2002;235:458–463. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bujko K, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, et al. Prediction of mesorectal nodal metastases after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: results of a randomised trial: implication for subsequent local excision. Radiother Oncol. 2005;76:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goligher JC. The adequacy of the marginal blood-supply to the left colon after high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during excision of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1954;41:351–353. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004116804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan CN, Griffiths JD. High ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery during operations for carcinoma of the distal colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1959;108:641–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fasth S, Hulten L, Hellberg R, Marston A, Nordgren S, Schioler R. Blood pressure changes in the marginal artery of the colon following occlusion of the inferior mesenteric artery. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1978;67:161–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lange JF, Komen N, Akkerman G, et al. Riolan’s arch: confusing, misnomer, and obsolete. A literature survey of the connection(s) between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. Am J Surg. 2007;193:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moriya Y. Function preservation in rectal cancer surgery. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:339–343. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0608-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Havenga K, Maas CP, DeRuiter MC, Welvaart K, Trimbos JB. Avoiding long-term disturbance to bladder and sexual function in pelvic surgery, particularly with rectal cancer. Semin Surg Oncol. 2000;18:235–243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2388(200004/05)18:3<235::AID-SSU7>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou ZG, Hu M, Li Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1211–1215. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koda K, Saito N, Seike K, Shimizu K, Kosugi C, Miyazaki M. Denervation of the neorectum as a potential cause of defecatory disorder following low anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:210–217. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruch HP, Schwandner O, Schiedeck TH, Roblick UJ. Actual standards and controversies on opzerative technique and lymph-node dissection in colorectal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s004230050187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wexner SD. Invited editorial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:987–989. doi: 10.1007/BF02237386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brennan DJ, Moynagh M, Brannigan AE, Gleeson F, Rowland M, O’Connell PR. Routine mobilization of the splenic flexure is not necessary during anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:302–307. doi: 10.1007/10350-006-0811-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hartley JE, Mehigan BJ, Qureshi AE, Duthie GS, Lee PW, Monson JR. Total mesorectal excision: assessment of the laparoscopic approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:315–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02234726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, et al. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:281–289. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morino M, Parini U, Giraudo G, Salval M, Brachet CR, Garrone C. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: a consecutive series of 100 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:335–342. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pikarsky AJ, Rosenthal R, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:558–562. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-8250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]