Abstract

Cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductases are involved in many physiological processes, including iron uptake in yeast, the respiratory burst, and perhaps oxygen sensing in mammals. We have identified a cytosolic cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase in mammals, a flavohemoprotein (b5+b5R) containing cytochrome b5 (b5) and b5 reductase (b5R) domains. A genetic approach, using blast searches against dbest for FAD-, NAD(P)H-binding sequences followed by reverse transcription–PCR, was used to clone the complete cDNA sequence of human b5+b5R from the hepatoma cell line Hep 3B. Compared with the classical single-domain b5 and b5R proteins localized on endoplasmic reticulum membrane, b5+b5R also has binding motifs for heme, FAD, and NAD(P)H prosthetic groups but no membrane anchor. The human b5+b5R transcript was expressed at similar levels in all tissues and cell lines that were tested. The two functional domains b5* and b5R* are linked by an approximately 100-aa-long hinge bearing no sequence homology to any known proteins. When human b5+b5R was expressed as c-myc adduct in COS-7 cells, confocal microscopy revealed a cytosolic localization at the perinuclear space. The recombinant b5+b5R protein can be reduced by NAD(P)H, generating spectrum typical of reduced cytochrome b with alpha, beta, and Soret peaks at 557, 527, and 425 nm, respectively. Human b5+b5R flavohemoprotein is a NAD(P)H oxidoreductase, demonstrated by superoxide production in the presence of air and excess NAD(P)H and by cytochrome c reduction in vitro. The properties of this protein make it a plausible candidate oxygen sensor.

Cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase has been demonstrated to be involved in many physiological processes, including the respiratory burst in mammalian neutrophils and macrophages as well as iron uptake in yeast. The neutrophil gp91PHOX-based protein complex and its yeast homologs, ferric reductases FRE1 and FRE2, are the only cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductases well-characterized so far. After bacterial or fungal engulfment by neutrophils or macrophages, gp91PHOX, coupled with p22PHOX on plasma membrane, is activated on the binding of p47PHOX, p67PHOX, and other cytosolic proteins to form a robust NAD(P)H oxidase complex (1). A nonphagocytic gp91PHOX-like protein, Mox1, has been found in human colon cancer cell line Caco-2 and some restricted tissues (colon, prostate, and uterus) and shown to transform embryonic cells when overexpressed (2). The yeast FRE1 and FRE2 have been shown to reduce ferric ion before transport across the cell membrane (3). Each gp91PHOX protein contains one FAD and two heme moieties, all with different redox potentials (4).

A cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase has been proposed as the oxygen sensor in animal cells. Studies in the human hepatoma cell line Hep 3B, which produces erythropoietin in response to hypoxia, suggest that the oxygen sensor is a heme protein (5). Transfection of mammalian cell lines using a luciferase reporter construct under the regulation of a hypoxia-responsive element demonstrated that the hypoxia inducible factor dependent oxygen sensing and signaling pathway is widespread (6). Moreover, spectral measurements in rat carotid body glomus cells have revealed the presence of a cytochrome b-type protein that may function as an oxygen sensor, regulating chemoreceptor activity by its NAD(P)H oxidase activity and formation of hydrogen peroxide (7). A hypoxia-sensitive and cyanide- and antimycin-insensitive cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidase also was found in the human hepatoma cell line Hep G2 (8). Because gp91PHOX seems not to be involved in oxygen sensing (9, 10) and the Mox1 transcript (EST176696, GenBank accession no. AA305700) was not found in human hepatoma cell lines Hep 3B and Hep G2 (H.Z. and H.F.B., unpublished data), we have searched for other specific NAD(P)H oxidases as candidate oxygen sensing proteins.

Cytochrome b5 (b5) and b5 reductase (b5R) are important redox proteins widespread in living organisms and involved in many physiological processes. Both the classical b5 and b5R both are bound to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane in all animal cells, where they participate in a fatty acid desaturation complex. Soluble forms of b5 and b5R catalyze methemoglobin reduction in erythrocytes, and mutations either in the b5 gene or, much more commonly, in the b5R gene can cause congenital methemoglobinemia (11). In addition, soluble b5 has been purified as a cytosolic component in the NAD(P)H-reductive activation pathway for porcine methionine synthase (12). b5R has been isolated from plants as a membrane-bound ferric-chelate reductase (13) and from animal plasma membranes as a coenzyme Q reductase that seems to stabilize ascorbate (14). All membrane-bound and soluble forms of b5 and b5R, as described above, are derived from their cognate genes by alternative splicing and/or posttranslational cleavage (15).

b5 may serve as a functional module interacting with another domain in a fusion protein. For example, b5 is fused to a reductase in animal sulfite oxidase, plant and bacterial nitrate reductases, and yeast cytochrome b2 (16). It also is fused to an acyl-CoA desaturase to form an alternative fatty acid desaturase in human (17) and yeast (18) as wells as in algae (19) and plants (20). In like manner, b5R can provide a functional domain in fusion with a globin domain to form flavohemoglobins as found in yeast (21, 22) and bacteria (23, 24). The wide existence of b5 and b5R, either as single-domain proteins or in fusion forms, reflects their ancient history and their important roles in diverse physiological processes.

Here we report the identification of a cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase, a fusion of b5 and b5R. The “b5+b5R” gene is found in human, mouse, rat, and nematodes and is expressed ubiquitously in human cells. Its structural, biochemical, and expression features fulfill many criteria of an oxygen sensor.

Materials and Methods

Reverse Transcription–PCR (RT-PCR), cDNA Cloning, and Mammalian Expression Construct with c-myc Tag.

Total RNA was prepared from Hep 3B cells with Trizol reagent (GIBCO/BRL) and reverse-transcribed into single-strand cDNA by avian myeloblastosis virus-reverse transcriptase using a 20-mer oligo(dT) as primer (25). The resulting single-strand cDNA pool was used as template in RT-PCRs with gene-specific primers (25). PCR products were ligated directly into the pCR3.1 vector (Invitrogen) for cloning and expression in mammalian cells. All clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing in both directions by using the dideoxy method (T7 Sequenase from United States Biochemical).

A gene-specific primer corresponding to the peptide NH2-EQKLISEEDL-COOH (near the COOH terminus of human c-myc protein), along with another primer for vector sequences, was used in PCR to add the c-myc tag to the NH2 terminus of human b5+b5R protein [5′-CCCATGGAGCAAAAGCTTATTTCTGAAGAGGACTTGGATTGGATTCGACTGACC-3′] or to the COOH terminus of human b5R protein [5′- TTACAAGTCCTCTTCAGAAATAAGCTTTTGCTCGAAGACGAAGCAGCGCTC-3′].

Cell Culture and Cell Transfection.

Hep 3B and COS-7 cell lines were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection and maintained in Alpha Minimum Essential Medium and DMEM (GIBCO/BRL), respectively, with 10% FCS and 1% streptomycin and penicillin. The calcium phosphate method, as described elsewhere (26), was used to transfect COS-7 cells (10 μg DNA construct for each 105 cells).

Northern Blot Analysis.

Human multiple tissue and multiple cell-line Northern blots were purchased from CLONTECH. The blots were hybridized in UltraHyb solution (Ambion) to a gene-specific cDNA probe radiolabeled by using a random priming method (kit RP1601N from Amersham Pharmacia) and washed at high stringency in 0.1× SSC and 0.1% SDS at 55°C. Blots were stripped in 0.5% SDS at 95–100°C for 10 min and reprobed up to 10 times without any obvious loss of signal.

Western Blot Analysis.

Cells grown on tissue culture dishes were washed twice with PBS buffer and lysed directly in SDS-gel loading buffer (25). Approximately 10 μg protein was loaded in each lane of a 10% gel (1.0 or 1.5 mm thick, with mini-gel apparatus from Bio-Rad) for SDS/PAGE (25). The protein gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (25). The Western blots were blocked in 5% nonfat milk, hybridized to antibodies in 2% nonfat milk, and developed with the ECL detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia).

Confocal Microscopy.

COS-7 transfectants were grown on glass slides before being fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, permeablized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked with 0.4% BSA. Mouse antibody 9E10 (primary, 1:500 dilution, from Sigma) against the c-myc peptide and rhodamine-conjugated donkey antimouse antibody (secondary, 1:500 dilution, from Roche) were used subsequently to hybridize with c-myc-tagged proteins. Negative controls include secondary antibody alone and no antibody. Confocal microscopy was performed by using a Bio-Rad MRC-1024/2P microscope in standard confocal mode using a Krypton-Argon laser. Images were obtained with ×63 objectives by using the lasersharp program.

Preparation of Escherichia coli Expression Construct and Protein Purification.

The expression constructs for b5+b5R protein and its single-domain derivatives b5* and b5R* were prepared by inserting coding sequences of the corresponding region into the pET19b vector (Novagen) by using NdeI and BamHI cloning sites at the NH2 and COOH ends, respectively.

The plasmid DNAs were transformed into BL21.DE3 competent cells and plated onto LB medium with 0.05 mg/ml ampicillin (Amp). A single colony was cultured in 2 liters of LB-Amp at 37°C with vigorous shaking until its OD600 reading reached ≈1.5. The culture then was quickly cooled to ≈8°C in ice water before isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 1 mM. The IPTG induction for protein expression was carried out overnight under gentle shaking at 4–8°C. The same temperature was used for all the following steps. Cell pellets, collected by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min, were resuspended in 50 ml cell lysis buffer (50 mM NaPi, pH 7.4/500 mM NaCl/20 mM MgCl2/1 mM PMSF) and lyzed for 4 hr with 3 mg/ml lysozyme (Sigma) and 8 units/ml DNase and 8 units/ml RNase (both from Roche). Cell lysates were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min and loaded at a flow rate of 0.2–0.5 ml/min onto a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid metal chelex column (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, 1 ml bed volume in a 1 cm × 15 cm column, equilibrated with high-salt buffer: 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.4/500 mM NaCl). The column was washed with high-salt buffer plus 20 mM imidazole, and the His10-tagged proteins were eluted with high-salt buffer plus 200 mM imidazole. Fractions with OD412 > 1 were pooled and dialyzed excessively against a low-salt buffer (20 mM NaPi, pH 7.4/50 mM NaCl). Protein samples were aliquoted, quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C until use.

Spectral Analysis for Light Absorption and NAD(P)H-Reductase Activity.

Light absorption spectral analysis was performed on a dual-beam spectrophotometer UV-2000 (Hitachi, Tokyo) at room temperature. Low-salt buffer (20 mM NaPi, pH 7.4/50 mM NaCl) was used in all measurements. Cytochrome c reductase activity was monitored spectrophotometrically as the formation of reduced cytochrome c (an increase of OD417) over a 15-min time course. All absorbance data from above were saved in text files and processed with excel 4.0 (Microsoft). Protein concentration was measured by Protein Assay system (Bio-Rad) with BSA (Pierce) as standard.

Chemiluminescence Measurement for NADH-Oxidase Activity.

NAD(P)H oxidase activity, expressed as production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), was measured by the Luminol + horseradish peroxidase (HRP) method (modified from ref. 27). All reagents were purchased from Sigma, except HRP (Calbiochem). Substrates for ROS production (NADH) and for detection (Luminol and HRP) were added into the b5+b5R sample and incubated at 37°C in two different ways: (i) addition of Luminol + HRP → 2 min → addition of NADH → 2 min, or (ii) addition of NADH → 2 min → addition of Luminol + HRP → 2 min. Chemiluminescence was measured for 20 sec on a Monolight luminometer 2010 (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego) immediately after the second incubation.

Results

Protein and Gene Structure.

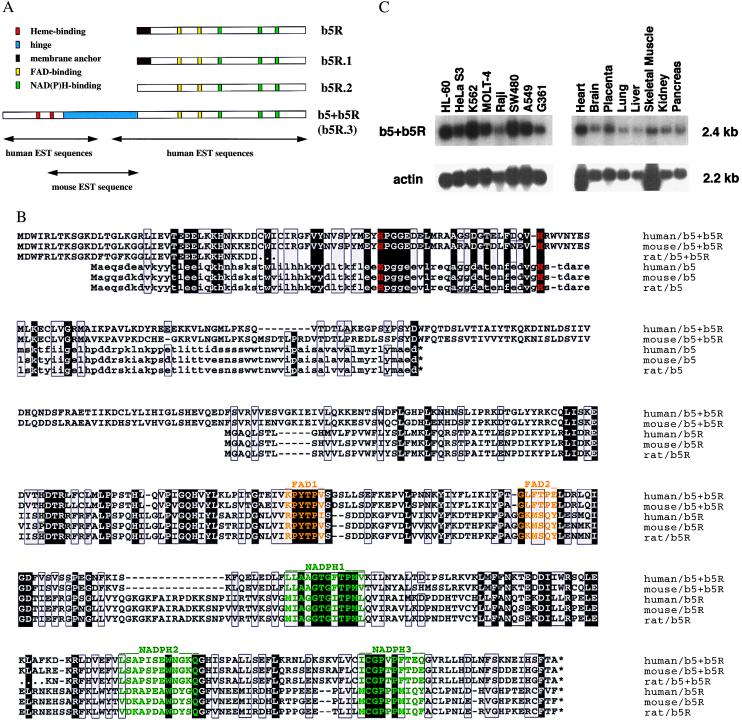

Human cDNA sequences encoding two previously unreported b5Rs (b5R.1 and b5R.2) and a fusion flavohemoprotein b5+b5R were obtained by blast searches (28) of expressed sequence tag (EST) databases for consensus NAD(P)H and flavin binding sites. Reverse transcription–PCR then was used to clone full-length cDNAs from the human hepatoma cell line Hep 3B (Fig. 1A). For the human b5+b5R cDNA, one mouse EST entry (GenBank accession no. AA762399) was found to link two separated clusters of human EST sequences to generate a long ORF spanning 487 aa residues. The complete transcript is ≈2.4 kb long and found in all cell lines and tissues tested as shown in Fig. 1C. This ubiquitous occurrence is supported by the sources for b5+b5R in dbest (list not shown). The same Northern signal has been obtained with cDNA probes from both domains, b5* and b5R*. The transcript level in Hep 3B was not significantly affected by hypoxia, cobalt and desferroxamine treatment, whereas erythropoietin gene expression, as expected, was up-regulated (data not shown).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of cDNA cloning for b5R.1, b5R.2, and b5+b5R in human. Amino acid sequences of the classical human b5R (GenBank accession no. P00387) were used as the template for tblastn searches (28) against dbest available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Matched EST entries with homologous (but not identical) encoded amino acid sequences were used for a further alignment to form a consensus polypeptide sequence. The well-conserved FAD- and NAD(P)H-binding sites (in yellow and green boxes, respectively) were used to anchor the alignment. Three b5R-like cDNA consensus sequences (b5R.1, b5R.2, and b5R.3) were found; b5R.3 seemed to have an open 5′ end. With the 5′ EST entry (GenBank accession no. AA166937) of human b5R.3 as the template for blastn search, one mouse EST entry (AA762399) was found to match with the human b5R.3 at its COOH half and with known cytochrome b5 sequences at its NH2 half, including the well-conserved two histidines (in red boxes). This mouse EST was further used as the template for another blastn search to find two human EST entries AA400638 and AA360693 corresponding to the b5* domain. The two clusters of human EST sequences for b5* and b5R* domains belong to the same cDNA (renamed as b5+b5R), which has an ORF of 487 aa residues containing both b5* and b5R.3 domains, linked by a hinge of about 100 residues long (colored in blue). The membrane anchors of b5R and b5R.1 are indicated as brown boxes. (B) Sequence alignment for b5+b5R and classical b5 and b5R proteins in human, mouse, and rat. One letter code (standard) is used for each of the 20 aa residues. Efforts were made to minimize the number of gaps by anchoring the well-conserved binding motifs for heme, FAD, and NAD(P)H (colored in red, yellow, and green, respectively). Identical residues are boxed in black, and chemically similar ones in gray. Gaps are indicated by -, unidentified residues in rat b5+b5R by ., and stop codons by *. GenBank accession numbers are: AF169803 (human b5+b5R), P10067 (human b5), P56395 (mouse b5), P00173 (rat b5), P00387 (human b5R), P20070 (rat b5R), H33691 (rat b5+b5R NH2 end), and AI071770 (rat b5+b5R COOH end). Amino acid sequences for mouse b5+b5R are translated from compository nucleotide sequences of all available EST entries in GenBank, including AA791608, AA762399, AA117503, and AI464992. Sequences for mouse b5R are also from EST entries, including AA870211, W77006, AA168906, and AA762398. All EST-derived sequences may contain error(s) from DNA sequencing. (C) Tissue and cell-line distribution of the human b5+b5R transcript. Both multiple tissue and multiple cell-line Northern blots, purchased from CLONTECH, were hybridized at high stringency to gene-specific cDNA probe for human b5+b5R (reverse transcription–PCR fragment for b5* or b5R*) and for human actin (CLONTECH). Approximately 2 μg poly(A)+ RNA was loaded in each lane. HL-60, promyelocytic leukemia; HeLa S3, epitheloid carcinoma (cervix); K-562, chronic myelogenous leukemia; MOLT-4, lymphoblastic leukemia; Raji, Burkitt's lymphoma; SW480, colorectal adenocarcinoma; A549, lung carcinoma; G361, melanoma.

One of the other two b5Rs, b5R.1, also was expressed in virtually all cells and tissues tested, whereas the expression of b5R.2 was considerably more restricted (results not shown). Because b5+b5R was presumed, and subsequently demonstrated, to be a heme protein and an NAD(P)H oxidoreductase, it is a candidate oxygen sensor and therefore became the focus of further studies.

The entire gene for human b5+b5R, except its 5′ end, is contained in clone dj676J13 (GenBank accession no. AL034347) physically located on chromosome 6. There are at least 13 introns in the coding region, i.e., at least four in the b5* domain, three in the hinge, and six in the b5R* domain. All splicing sites in the b5+b5R gene are in positions different from those in the classical b5 and b5R genes (data not shown). The Kozak sequences for human, mouse, and rat b5+b5R and rat mitochondrial b5 are considered adequate for translation initiation, whereas all ER-membrane-bound b5 and b5R genes have a strong site (29).

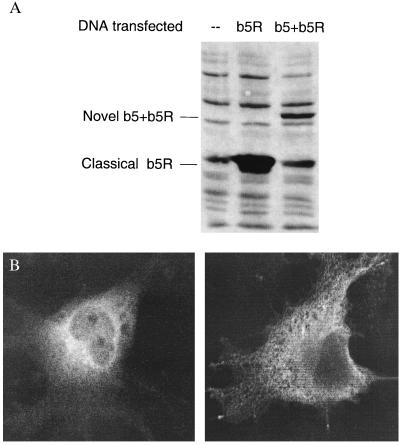

This b5+b5R fusion protein is different from the classical ER membrane-bound b5 and b5R in three respects (see sequence alignment in Fig. 1B): (i) There are unique sequences around well-conserved residues involved in the binding of heme, FAD, and NAD(P)H, i.e., one missing and one additional residue around the second heme-binding histidine, and two additional residues both after the FAD1 site and before the NADPH3 site. (ii) There is no membrane anchoring structure, i.e., neither integral membrane sequence nor a potential myristylation site, compared with the classical b5R, which has both integral membrane sequences and a myristylation site at its NH2 terminus. (iii) The hinge region, which is not present in classical b5 and b5R, is much less conserved between human and mouse as compared with the highly homologous b5* and b5R* domains. The human b5+b5R protein seems less stable than the classical b5R when overexpressed in COS-7 cells as c-myc adducts (Fig. 2A). The b5+b5R protein is localized in the cytosol close to the perinuclear space, as shown by b5+b5R-specific signals with confocal microscopy (Fig. 2B Left), whereas the ER membrane-bound classical b5R is localized on intracellular membrane as expected (Fig. 2B Right). The signals from confocal microscopy were specific for c-myc adducts, because there was no signals from secondary antibody alone and no antibody controls (data not shown). The presence of c-myc peptide sequences has been shown not to affect the subcellular localization of overexpressed c-myc adducts in COS-7 cells for proteins such as b5R in our hands and b5 in ref. 30.

Figure 2.

(A) Transient expression of the human b5+b5R protein in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells (from monkey kidney) were transfected with expression construct (in pCR3.1 vector, Invitrogen) for classical b5R with c-myc tagged at the COOH end or b5+b5R tagged at the NH2 end. Total cell lysate was collected after 2 days of transient expression and subjected to SDS/PAGE analysis. Approximately 10 μg of total protein was loaded onto each lane and the Western blot was hybridized with mouse antibody 9E10 against c-myc tag. (B) Confocal microscopy for subcellular localization of the human b5+b5R protein. COS-7 cells were grown on glass slide for 2 days after the transfection. Mouse antibody 9E10 and a rhodamine-conjugated donkey antimouse antibody were used to hybridize with c-myc-tagged proteins. b5+b5R (Left) and classical b5R (Right) are shown.

Biochemical Properties.

Functional human b5+b5R proteins were overexpressed in an E. coli system (Fig. 3A) in recombinant forms (His10-tagged at the NH2 end), either as a fusion protein with or without hinge (b5+b5R and b5+b5R.ΔH, respectively) or as single-domain proteins (b5* and b5R*). The gene for the RNA polymerase responsible for transcribing the gene of interest was under the control of a lac promoter. When induced by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), E. coli host cells first make RNA polymerase then the b5+b5R fusion protein. Two major concerns for overexpressing any foreign protein in a bacterial system are protein solubility and stability. When expressed at 37°C, the b5+b5R protein was mainly inside inclusion bodies and largely degraded into smaller fragments, as detected by Western analysis using an anti-His10-tag polyclonal antibody (data not shown). Both solubility and stability were greatly improved when the temperature for IPTG induction and protein expression was lowered to 4°C.

Figure 3.

(A) Expression constructs for human b5+b5R protein and its derivatives. The constructs for b5+b5R fusion as well as b5* and b5R* single-domain proteins were made by inserting PCR fragments into the pET-19b vector (Novagen), using NdeI site at the NH2 end and BamHI site at the COOH end (both sites were included in PCR primers). The b5* domain extends from the NH2 terminus through the NH2-PSYPSF-COOH peptide sequences, and the b5R* domain from the NH2-GQHVYLK-COOH peptide sequences through the COOH terminus of b5+b5R. The b5+b5R.ΔH was constructed by ligating the following DNA pieces: NdeI–NheI fragment for b5*, NheI–BamHI fragment for b5R*, and NdeI–BamHI fragment for pET19b vector. The presence of His10 tag and enterokinase cleavage site at the NH2 terminus of recombinant protein is indicated. (B) Light absorption spectrum for the human b5+b5R protein. Spectrum was measured at room temperature under air in low-salt buffer, either with 2 μM b5+b5R alone (oxidized) or mixed with additional 0.1 mM NADH (NADH-reduced). Excess NAD(P)H was necessary to maintain the b5+b5R protein in reduced state under aerobic conditions.

Recombinant b5+b5R protein can reduce its heme moiety by consuming NAD(P)H, generating a typical light absorption spectrum of reduced cytochrome b with α, β, and Soret peaks at 557, 527 and 425 nm, respectively (Fig. 3B). In addition to these peaks, the difference spectrum (NADPH-reduced minus oxidized, data not shown) showed a valley at 408 nm, which represented the completely oxidized form. Therefore, recombinant b5+b5R protein was mostly oxidized (Soret peak at 412 nm) after being purified from E. coli cell lysate. Cyanide (20 mM) had no effect on the NAD(P)H reduction of ferric heme in the b5+b5R protein (data not shown). The ferric heme also can be reduced chemically by dithionite, generating the same spectrum as above (data not shown). The b5+b5R protein was reoxidized when exposed to air after the reducing agent, either NAD(P)H or dithionite, was consumed. Using the difference in absorption between 424 and 410 nm for reduced b5 [ɛ(424–410) = 185 mM−1⋅cm−1] (31), the heme content in recombinant b5+b5R protein was calculated as one per molecule.

Cytochrome c reductase activity for recombinant human b5+b5R protein is shown in Fig. 4A. This protein has a very high specific activity for cytochrome c, even greater than cytochrome c reductase. The NADH-oxidase activity, measured as production of ROS under normoxia and in excess of NADH, was inhibited completely by 1,000 units of superoxide dismutase (SOD) or 30 μM diphenylene iodonium (DPI), or 80% at 1 μM DPI (Fig. 4B). The same pattern of ROS production has been observed for xanthine and xanthine oxidase complex (100 μM and 0.1 unit, respectively; data not shown). Neither NAD(P)H reductase nor NAD(P)H oxidase activity was observed for b5+b5R.ΔH or the mixture of b5* and b5R* single-domain proteins (data not shown). Therefore, the hinge region between b5* and b5R* domains is important for maintaining the proper conformation and/or intermolecular and intramolecular electron flow.

Figure 4.

(A) NADH-reductase activity with cytochrome c as substrate. Cytochrome c reduction was monitored at 417 nm (Soret peak for reduced cytochrome c) at room temperature under air. Light absorption was followed for 15 min, beginning immediately after mixing the sample. Substrate = 6 μM oxidized cytochrome c; reductant = 1 mM NADH; sample = 0.03 μM b5+b5R (with or without 30 μM DPI), or 0.125 μM cytochrome c reductase. Nearly identical data were obtained three times. A representative time course is shown here. (B) Superoxide production. The production of ROS was measured by the Luminol + HRP method. The b5+b5R protein (0.1 μM) and NADH (0.5 mM) were used as the components for ROS production, whereas Luminol (3 mM) and HRP (0.05 mg/ml) were used for ROS detection. Inhibitors tested: DPI (1 μM or 30 μM) and SOD (1,000 units).

Discussion

Flavohemoprotein.

We describe the cloning and partial characterization of a cytochrome b/cytochrome b5 reductase fusion protein. Homologues of the human b5+b5R flavohemoprotein are present in mouse, rat, and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (gene Y52B11A.3, GenBank accession no. AL032654). Similar fusion proteins containing a b5 and a NAD(P)H-reductase domain include animal sulfite oxidases, plant and bacterial nitrate reductases, and yeast cytochrome b2 (16). Both the sulfite oxidase and the nitrate reductase have a third domain for binding of molybdenum cofactor, in addition to b5 and b5R domains. Yeast cytochrome b2 has a different reductase domain that binds FMN. Therefore, the b5+b5R fusion proteins described here represent an additional class of flavohemoproteins in animals.

Functional Role.

Human b5+b5R protein has been shown to be a good NAD(P)H reductase in vitro on artificial substrates, such as cytochrome c (Fig. 4A) as well as ferric ion and methemoglobin (data not shown). It also can reduce its own heme moiety by consuming NAD(P)H, resulting in the conversion of oxygen to ROS under aerobic conditions. This NAD(P)H-oxidase activity, further measured by chemiluminescence, was shown to be effectively inhibited by SOD or DPI, a riboflavin structural analog. Therefore, as expected, FAD is necessary to mediate the electron flow from NAD(P)H (a two-electron donor) to heme (a one-electron acceptor) and eventually to an oxygen molecule. The ROS generated by this reaction is superoxide, as shown by ablation of chemiluminescence when SOD was added. Superoxide can be further converted both enzymatically and spontaneously into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, which can generate other ROS.

The physiological function of this b5+b5R protein remains to be established. There is some evidence to support its possible role as a universal oxygen sensor in vivo. It has been proposed that a cytochrome b-type NAD(P)H oxidoreductase is involved in the oxygen sensing and signaling pathway by generating ROS under normoxia, therefore modifying downstream target(s) like the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor 1 (as reviewed in ref. 32). The formation of hydrogen peroxide and other ROS, likely mediated by local Fenton chemistry, has been demonstrated in perinuclear space of Hep G2 cells (33). The similar subcellular location of an active NAD(P)H oxidase b5+b5R (as the c-myc adduct) suggests a possible link between this oxidase, ROS production, and oxygen sensing. The widespread distribution of b5+b5R mRNA and lack of response to changes in oxygen tension also fits our current model for a universal oxygen sensor (32, 34).

Function of Hinge.

The hinge region between the b5 and b5R domains has been shown to modulate intramolecular electron flow in cytochrome b2 (35). This interference could be achieved directly by disruption of the electron flow through important side chains, or indirectly by distortion of protein conformation, especially in heme- and/or flavin-binding domains, or both. We have shown that the hinge in the human b5+b5R protein is critical for its NAD(P)H-oxidoreductase activity. Because two pairs of charged residues (36) responsible for the proper docking of classical b5 and b5R on the ER membrane are not found in b5+b5R protein, its hinge region seems to fulfill the structural requirement for maintaining the proper contact to allow electron flow between functional sites within the two domains. The variability of hinge region sequences between human and mouse b5+b5R proteins also suggests this structural role. Deletion of the hinge seems to cause no significant conformation change in the heme domain as suggested by the same light absorption spectra observed for wild-type b5+b5R, mutant b5+b5R.ΔH, and single-domain b5* proteins (data not shown). It is also possible that some unknown functions (e.g., subcellular localization, protein interaction, etc.) are encoded within the hinge region, because its large size (>100 residues) may be more than necessary to serve only as a structural linker.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Gorr for help on computer graphics and Peter Marks at the Confocal Microscopy Core Facility of Brigham and Women's Hospital. This work is supported by RO1 DK41234 (H.F.B.) and F32 DK09678 (H.Z.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- b5

cytochrome b5

- b5R

cytochrome b5 reductase

- b5+b5R

fusion protein containing b5- and b5R-like domains

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EST

expressed sequence tag

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- DPI

diphenylene iodonium

Note Added in Proof:

The existence of another nonphagocytic gp91PHOX-like protein has been implicated by EST sequences from human (GenBank accession nos. AI885681 and AI742260), mouse (AI314159 and AI746441), and rat (AA892258). However, human multiple tissue and cell line Northern blots have revealed the transcript only in kidney (data not shown).

Footnotes

References

- 1.Babior B M. Adv Enzymol. 1992;65:49–95. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh Y A, Arnold R S, Lassegue B, Shi J, Xu X, Sorescu D, Chung A B, Griendling K K, Lambeth J D. Nature (London) 1999;401:79–82. doi: 10.1038/43459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dancis A, Klausner R D, Hinnebusch A G, Barriocanal J G. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.5.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finegold A A, Shatwell K P, Segal A W, Klausner R D, Dancis A. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31021–31024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg M A, Dunning S P, Bunn H F. Science. 1988;242:1412–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.2849206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell P H, Pugh C W, Ratcliffe P J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2423–2427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.6.2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross A R, Henderson L, Jones O T G, Delpiano M A, Hentschel J, Acker H. Biochem J. 1990;272:743–747. doi: 10.1042/bj2720743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Görlach A, Holtermann G, Jelkmann W, Hancock J T, Jones S A, Jones O T G, Acker H. Biochem J. 1993;290:771–776. doi: 10.1042/bj2900771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wenger R H, Marti H H, Schuerer-Maly C C, Kvietikova I, Bauer C, Gassman M, Maly F E. Blood. 1996;87:756–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Archer S L, Reeve H L, Michelakis E, Puttagunta L, Waite R, Nelson D P, Dinauer M C, Weir E K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7944–7949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunn H F. In: Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. Nathan D G, Orkin S H, editors. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998. pp. 729–761. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Z, Banerjee R. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26248–26255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagnaresi P, Thoiron S, Mansion M, Rossignol M, Pupillo P, Briat J F. Biochem J. 1999;338:499–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villalba J M, Navarro F, Gomez-Diaz C, Arroyo A, Bello R I, Navas P. Mol Aspects Med. 1997;18:S7–S13. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(97)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulbarelli A, Valentini A, DeSilvestris M, Cappellini M D, Borgese N. Blood. 1998;92:310–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lederer F. Biochimie. 1994;76:674–692. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho H P, Nakamura M T, Clarke S D. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:471–477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn T M, Haak D, Monaghan E, Beeler T J. Yeast. 1998;14:311–321. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980315)14:4<311::AID-YEA220>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakuradani E, Kobayashi M, Shimizu S. Eur J Biochem. 1999;260:208–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Napier J A, Sayanova O, Stobart A K, Shewry P R. Biochem J. 1997;328:717–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu H, Riggs A F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5015–5019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwaasa H, Takagi T, Shikama K. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:948–954. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90236-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasudevan S G, Armarego W L F, Shaw D C, Lilley P E, Dixon N E, Poole R K. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:49–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00273586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cramm R, Siddiqui R A, Friedrich B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7349–7354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu H, Belanger A, Yoon H W, Bunn H F. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11173–11176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson J L, Park J W, Benna J E, Faust L P, Inanami O, Babior B M. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35147–35152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak M. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:563–574. doi: 10.1007/s003359900171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuroda R, Kinoshita J, Honsho M, Mitoma J, Ito A. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1996;120:828–833. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arinc E, Cakir D. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:345–362. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu H, Bunn H F. Respir Physiol. 1999;115:239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(99)00024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kietzmann T, Porwol T, Zierold K, Jungermann K, Acker H. Biochem J. 1998;335:425–432. doi: 10.1042/bj3350425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunn H F, Poyton R O. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:839–885. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharp R E, Chapman S K, Reid G A. Biochem J. 1996;316:507–513. doi: 10.1042/bj3160507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawano M, Shirabe K, Nagai T, Takeshita M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:666–669. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]