Abstract

Cyanobacteriochromes are a newly recognized group of photoreceptors that are distinct relatives of phytochromes but are found only in cyanobacteria. A putative cyanobacteriochrome, CcaS, is known to chromatically regulate the expression of the phycobilisome linker gene (cpcG2) in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. In this study, we isolated the chromophore-binding domain of CcaS from Synechocystis as well as from phycocyanobilin-producing Escherichia coli. Both preparations showed the same reversible photoconversion between a green-absorbing form (Pg, λmax = 535 nm) and a red-absorbing form (Pr, λmax = 672 nm). Mass spectrometry and denaturation analyses suggested that Pg and Pr bind phycocyanobilin in a double-bond configuration of C15-Z and C15-E, respectively. Autophosphorylation activity of the histidine kinase domain in nearly full-length CcaS was up-regulated by preirradiation with green light. Similarly, phosphotransfer to the cognate response regulator, CcaR, was higher in Pr than in Pg. From these results, we conclude that CcaS phosphorylates CcaR under green light and induces expression of cpcG2, leading to accumulation of CpcG2-phycobilisome as a chromatic acclimation system. CcaS is the first recognized green light receptor in the expanded phytochrome superfamily, which includes phytochromes and cyanobacteriochromes.

Keywords: chromatic adaptation, phycocyanobilin, phytochrome, cyanobacteria, photoreceptor

Phytochromes (Phys) are photoreceptors that typically perceive red and far-red light and regulate a wide range of physiological responses in plants, bacteria, cyanobacteria, and fungi (1). They exhibit reversible photoconversion between two distinct forms: the red-absorbing form (Pr) and the far-red-absorbing form (Pfr). Their N-terminal photosensory region, which consists of Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS), cGMP phosphodiesterase/adenylyl cyclase/FhlA (GAF), and phytochrome domains, is highly conserved, but there are variations in the chromophore of the linear tetrapyrrole, such as phytochromobilin, phycocyanobilin (PCB), and biliverdin. It is reported that phytochromobilin or PCB is covalently anchored at a conserved cysteine residue in the GAF domain (2, 3), whereas biliverdin is anchored at another conserved cysteine residue in the N terminus of the PAS domain (4). The perception of light by Phys triggers a Z to E isomerization of the C15–C16 double bond between the C and D pyrrole rings as well as subsequent conformational changes of the chromophore and the apoprotein [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1] (5) which signal to downstream processes. Recent crystallographic analyses of bacterial Phys (DrBphP and RpBphP3) have revealed the three-dimensional structure of PAS and GAF domains in the Pr form (6–8). The biliverdin chromophore is buried deep within a pocket in the GAF domain with a configuration of C5-Z,syn/C10-Z,syn/C15-Z,anti. Because the residues in the chromophore-binding pocket are highly conserved, it was proposed that Phys share a common photoconversion mechanism, albeit with certain variations.

“Cyanobacteriochromes” are a newly recognized group of photoreceptors that possess putative chromophore-binding GAF domains that are related to but distinct from those of Phys (9). They were initially identified by mutational studies of some cyanobacteria, including a chromatic acclimation of phycobiliproteins in Fremyella diplosiphon (10), a light-induced reset of the circadian rhythm in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 (11), and light-induced mixotrophic growth (12) and phototaxis (13) in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. The pigment-binding and spectral properties were first revealed in the protein SyPixJ1, which is essential for positive phototaxis in a motile substrain of Synechocystis. SyPixJ1, isolated from Synechocystis, bound a linear tetrapyrrole covalently and showed reversible photoconversion between the blue-absorbing form and the green-absorbing form (Pg), in contrast with the red-absorbing Pr and far-red-absorbing Pfr of Phys (9). At first, the chromophore of SyPixJ1 was assumed to be PCB because its GAF domain showed similar photoconversion to the native protein when expressed in PCB-producing E. coli (14). However, subsequent denaturation analysis of PixJ homolog in Thermosynechococcus elongatus, TePixJ, revealed that the chromophore is not PCB but its isomer phycoviolobilin, suggesting autoisomerization of PCB to phycoviolobilin (15, 16). The disconnection of the conjugated π-electrons between pyrrole rings A and B in phycoviolobilin is suggested to be one of the reasons why TePixJ absorbs considerably shorter wavelength compared with Phys.

Many cyanobacteria modulate the biosynthesis of a photosynthetic light-harvesting antenna, phycobilisome, in response to ambient light conditions (17). It is reported that in some species green-light irradiation induces accumulation of a green-absorbing pigment, phycoerythrin, whereas red-light irradiation induces accumulation of a red-absorbing pigment, phycocyanin, in the phycobilisome (18). Because this process, termed complementary chromatic adaptation, is photoreversible, phytochrome-class photoreceptor(s) has been postulated to regulate this acclimation and has been explored by many laboratories. In the 1970s, photochromic pigments that showed slight green/red reversible conversion were found in extracts of some cyanobacteria (phycochromes), but they proved to be partially disintegrated phycobiliproteins (19, 20). Genetic studies of F. diplosiphon suggested that a putative cyanobacteriochrome, FdRcaE, is responsible for the red-light-induced expression of phycocyanin genes (21); however, its spectral properties and chemical species of the chromophore remain unknown (22). Further analysis suggested that another green-light-sensing system mainly regulates the expression of phycoerythrin genes (23).

Recently, the expression of phycobilisome linker gene cpcG2 has been reported to be chromatically regulated by a cyanobacteriochrome gene, ccaS, and a response regulator gene, ccaR, in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (24). It has been shown that (i) expression of cpcG2 is up-regulated by green-orange light at 550–600 nm, (ii) disruption of either ccaS or ccaR results in a dramatic decrease in cpcG2 expression, and (iii) CcaR directly binds to the promoter region of cpcG2 (M.K., X. X. Geng, M. Kobayashi, F. Yano, M. Kanehisa, and M.I, unpublished data). As CpcG2 forms atypical phycobilisome and is involved in energy transfer to photosystem I, this chromatic regulation of cpcG2 expression is considered as a new type of chromatic acclimation of Synechocystis (25, 26).

In this study, we demonstrate that CcaS undergoes photoconversion between the Pg and the Pr. The chromophore of CcaS appears to be PCB in a configuration of C15-Z and C15-E for Pg and Pr, respectively. The autophosphorylation of CcaS and the phosphotransfer to CcaR are up-regulated by green light. These data provide insight into how cyanobacteria control the expression of genes for phycobilisomes in response to changes in light conditions.

Results

Gene Arrangement and Domain Architecture.

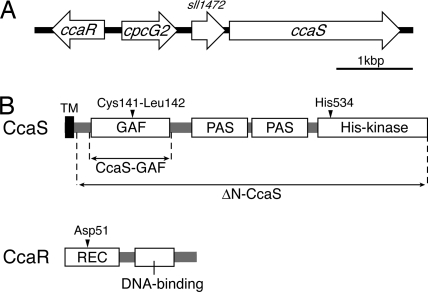

The Cca gene cluster is composed of the four genes cpcG2 (Cyanobase ID sll1471), a hypothetical gene (sll1472), ccaS (sll1473–5), and an upstream regulator gene ccaR (slr1584) with opposite orientation (Fig. 1A). Note that ccaS is interrupted by insertion sequence ISY203g, generating two inactive ORFs (sll1473 and sll1475) in the sequenced substrain, Kazusa, but is functional in the original strain, PCC (27, 28). The predicted CcaS protein consists of an N-terminal transmembrane helix, the cyanobacteriochrome-type GAF domain, two PAS domains, and a C-terminal histidine kinase domain (Fig. 1B). It should be mentioned that a chromophore ligation motif in the GAF domain is Cys-Leu for CcaS instead of Cys-His, as seen in plant Phys and other cyanobacteriochromes. The second PAS domain is similar to the light/oxygen/voltage domain of plant phototropins, but it lacks the cysteine residue that forms a flavin-cysteine adduct upon blue-light excitation (29). CcaR is a typical response regulator of the OmpR class, which consists of an N-terminal receiver domain and a C-terminal DNA-binding domain. His-534 of CcaS and Asp-51 of CcaR are predicted to be involved in autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer of the two-component phosphorelay system, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Molecular characterization of CcaS and CcaR. (A) Arrangement of cpcG2, ccaS, and ccaR on the chromosome of Synechocystis. (B) Predicted domain architecture of CcaS and CcaR. CcaS-GAF comprises 185 residues from position 53 to 237. ΔN-CcaS comprises 730 residues from position 24 to 753. TM, transmembrane; GAF, GAF domain; PAS, PAS domain; His-kinase, histidine kinase domain; REC, receiver domain; DNA-binding, DNA-binding domain.

Purification and Spectral Analysis of the GAF Domain.

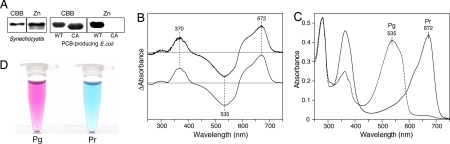

We first expressed the GAF domain of CcaS (CcaS-GAF) with a His-tag in Synechocystis by using the trc promoter system (15). The band of purified CcaS-GAF in SDS/PAGE strongly fluoresced after incubation with Zn2+ (Fig. 2A), indicating covalent binding of a linear tetrapyrrole chromophore (30). The purified protein showed no obvious peaks for CcaS in the absorption spectrum due to the relatively abundant chlorophylls and some carotenoids. However, irradiation of this preparation with green light caused a significant decrease in the green region and a concomitant increase in the red region of the absorption spectrum (Fig. S2). Irradiation with red light had the opposite effect on the absorption spectrum. The difference spectrum of green-minus-red showed a photoconversion between the two distinct spectral forms: the Pg peaked at 535 nm and the Pr peaked at 672 nm (Fig. 2B, upper line). Such photoconversion was repeated several times without any changes, indicating full photoreversibility.

Fig. 2.

Purification and spectral analysis of the GAF domain. (A) CcaS-GAF was purified from both Synechocystis and PCB-producing E. coli. Cys141Ala mutant (CA) was prepared from PCB-producing E. coli. The SDS/PAGE gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) after monitoring for Zn2+-induced fluorescence (Zn). (B) Difference absorption spectra of green-light irradiation minus red-light irradiation of CcaS-GAF isolated from Synechocystis (upper line) and PCB-producing E. coli (lower line). (C) Absorption spectra of the Pg (dashed line) and Pr (solid line) of CcaS-GAF from E. coli. (D) Photographs of solutions of Pg and Pr of CcaS-GAF from E. coli.

We also purified CcaS-GAF from E. coli by using the chromophore coexpression system (31). When PCB was coexpressed, the chromophore-binding holoprotein was purified as a single band by SDS/PAGE that strongly fluoresced after incubation with Zn2+ (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, only the chromophore-free apoprotein was isolated when biliverdin, a precursor of PCB, was coexpressed (Fig. S3A). Irradiation with green light yielded a peak at 672 nm with a slight shoulder at 614 nm (Pr), whereas irradiation with the red light yielded a peak at 535 nm with a shoulder at 570 nm (Pg) (Fig. 2C). Fig. 2D shows a solution of CcaS-GAF in Pg and Pr forms. When CcaS-GAF was expressed in the dark, E. coli cells turned brownish-red, indicating that Pg was initially formed as a ground state (Fig. S3B). The difference spectrum of Pr-minus-Pg showed three major peaks: positive peaks at 672 nm and 370 nm and a negative peak at 535 nm (Fig. 2B, lower line). These are identical to peaks seen in the samples prepared from Synechocystis, suggesting that CcaS-GAF binds PCB as a natural chromophore.

Identification of Chromophore, Its Binding Site, and Configuration.

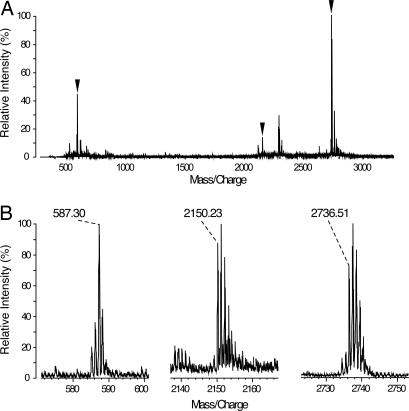

To identify the chromophore and its binding site, we isolated a tryptic chromopeptide by HPLC and analyzed it by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization quadrupole ion trap time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-QIT-TOF MS) (Fig. 3A). We detected signals of a desorbed chromophore at a m/z of 587.30, a chromophore-desorbed peptide at m/z 2151.23, and a chromophore-bound peptide at m/z 2736.51 (Fig. 3B). The chromophore signal corresponds to the calculated mass of a protonated PCB or its isomer (587.28). Further MS/MS analysis of these peptide fragments indicated that the peptide sequence is AINDIDQDDIEICLADFVK, which contains a conserved cysteine residue (Cys-141) (Fig. S4). These signals also indicate that the thiol group of Cys-141 was not carbamidomethylated, suggesting that Cys-141 forms a thioether bond with the chromophore. Site-directed mutagenesis of this cysteine to alanine (Cys141Ala) resulted in a loss of covalent binding of the chromophore even by detection of sensitive Zn2+-induced fluorescence (Fig. 2A). These results strongly suggest that PCB or its isomer is covalently anchored through Cys-141 via a thioether bond.

Fig. 3.

MALDI-QIT-TOF MS spectrum of the chromopeptide isolated by HPLC. (A) Whole MS spectrum of the purified chromopeptide. (B) Three major signals indicated with black triangles in A are enlarged. The ion signal at m/z 587.30 corresponds to the calculated mass of protonated PCB or its isomer (587.29). The m/z 2150.23 and 2736.51 correspond to the calculated mass of the chromophore-desorbed (2150.03) and chromophore-bound (2736.31) peptide AINDIDQDDIEICLADFVK, respectively.

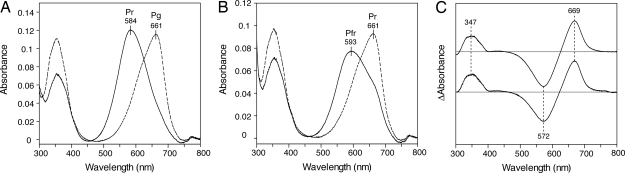

It is accepted that the tetrapyrrole configurations of Pr and Pfr of Phys are C5-Z/C10-Z/C15-Z (ZZZ) and C5-Z/C10-Z/C15-E (ZZE), respectively (32). These configurations can be distinguished by absorption spectra after denaturation of holoproteins (16). To identify the chemical species and configuration of the CcaS chromophore, we denatured the holoprotein isolated from E. coli with acidic urea and compared it with the cyanobacterial phytochrome Cph1, for which PCB is a natural chromophore (33, 34). The spectrum of the denatured Pg of CcaS-GAF (λmax = 661 nm) matched well with that of denatured Pr of Cph1 (λmax = 661 nm, Fig. 4 A and B). The spectrum of the denatured Pr form of CcaS-GAF (λmax = 584 nm) matched closely with that of the denatured Pfr of Cph1 (λmax = 593 nm) if incomplete photoconversion from Pr to Pfr is taken into consideration for Cph1. The difference spectra demonstrated that the chromophore photoconversion of CcaS-GAF between Pg and Pr was identical to that of Cph1 between Pr and Pfr (Fig. 4C). Denaturation analysis of CcaS-GAF and Cph1 at neutral pH is consistent with the result at acidic pH (Fig. S5). These results suggest that Pg and Pr of CcaS-GAF bind PCB in the configuration ZZZ and ZZE, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Denaturation analysis of CcaS and Cph1. Both absorbing forms of CcaS and Cph1 were denatured with 8 M urea at pH 2.0 in the dark. (A) Absorption spectra of denatured Pg (dashed line) and Pr (solid line) of CcaS-GAF. (B) Absorption spectra of denatured Pr (dashed line) and Pfr (solid line) of Cph1. (C) Difference absorption spectra of CcaS-GAF (upper line) and Cph1 (lower line).

Protein Kinase Assay.

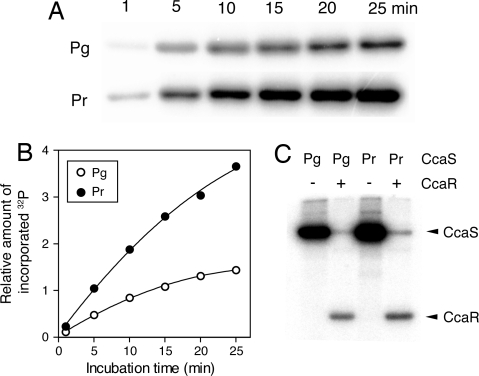

Because CcaS has a histidine kinase domain in the C-terminal region, we studied the effects of light irradiation on CcaS autophosphorylation activity. A truncated form of CcaS (ΔN-CcaS) lacking the N-terminal transmembrane helix (Fig. 1B) was expressed in Synechocystis. We obtained near-pure ΔN-CcaS and confirmed the covalently bound tetrapyrrole by Zn2+-induced fluorescence (Fig. S6A). The light-induced difference spectrum was identical to that of the GAF domain alone (Fig. S6B). In the dark, no conversion of either Pg to Pr or Pr to Pg was observed in incubation for 3 h at room temperature (data not shown). When ΔN-CcaS was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, the labeled phosphate was covalently incorporated into the protein in a time-dependent manner. When phosphorylation was performed in the dark after full photoconversion, we observed that the Pr form was more efficiently phosphorylated (by ≈2.5-fold) than the Pg form (Fig. 5 A and B). When autophosphorylated CcaS was incubated with the putative cognate response regulator CcaR, the phosphate was rapidly transferred to CcaR (Fig. 5C). Again, CcaR was more efficiently phosphorylated (by ≈1.5-fold) than the Pg form. These results clearly demonstrate that green light enhances the CcaS autophosphorylation and phosphotransfer to CcaR.

Fig. 5.

Protein kinase assays. (A) Autophosphorylation of Pg and Pr of ΔN-CcaS with [γ-32P]ATP in the dark. The reaction products were subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Quantitation of the radiolabel incorporated into Pg (open circles) and Pr (solid circles) in A. (C) Transfer of the phosphate from ΔN-CcaS to CcaR. Autophosphorylated Pg and Pr of ΔN-CcaS were incubated with the same amount of CcaR for 10 min in the dark.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that CcaS undergoes reversible photoconversion between Pg and Pr forms. The chromophore of CcaS is suggested to be PCB in configurations ZZZ for Pg and ZZE for Pr, which are covalently anchored at Cys-141. The autophosphorylation of ΔN-CcaS and phosphotransfer to CcaR were enhanced by green light.

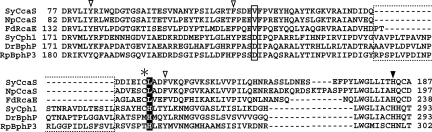

CcaS shows unique green/red photoreversibility that contrasts with conventional red/far-red photoreversibility of Phys. Our denaturation analyses revealed that the chromophore configuration is ZZZ for Pg and ZZE for Pr in CcaS, whereas it is ZZZ for Pr and ZZE for Pfr in Phys. This finding indicates that absorption peaks of both forms of CcaS are “blue-shifted” from those of Phys, suggesting that the conjugated π-electrons of the chromophore are shortened or distorted in the GAF domain of CcaS. GAF domains that are homologous to CcaS are found in the ortholog NpCcaS of the filamentous N2-fixing cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102 and in a putative cyanobacteriochrome FdRcaE of another filamentous cyanobacterium, F. diplosiphon. We compared these sequences with the GAF domains of DrBphP and RpBphP3, whose three-dimensional structure has been solved (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Protein alignment (CLUSTALX) of the chromophore-binding GAF domain of CcaS, its related cyanobacteriochromes, and Phys. CcaSs lack the sequences that form a part of the figure-of-eight knot in Phys (dashed-line boxed type). Cys-141 of CcaS (asterisk) is the chromophore-binding site. His-184 of CcaS (solid triangle) may form a hydrogen bond with the nitrogen of the D ring of PCB. Three aromatic residues (Tyr-82, Phe-109, and Phe-145 in CcaS, open triangles) form a hydrophobic cavity to hold ring D. A highly conserved Asp (solid-line boxed type) and His (highlighted type) in Phys are replaced with Val and Leu in CcaSs, respectively. SyCcaS is CcaS of Synechocystis in this study. NpCcaS is the ortholog of SyCcaS in N. punctiforme. FdRcaE is a putative cyanobacteriochrome of F. diplosiphon. Cph1, DrBphP, and RpBphP3 are phytochromes of Synechocystis, Deinococcus radiodurans R1, and Pseudomonas palustris CGA009, respectively.

CcaSs lack the “lasso” sequence in the figure-of-eight knot structure, which stabilizes the interaction of the preceding PAS with the GAF domains in Phys (7) (Fig. 6, dotted box). The absence of the lasso sequence and the PAS domain in CcaS is consistent with that the GAF domain alone is sufficient for the complete photocycle. Notably, all of the cyanobacteriochromes, including the phototaxis regulator, PixJ, lack the lasso sequence as well as the preceding PAS domain.

In regard to the chromophore-binding motifs, CcaSs are highly divergent from Phys but retain several key features. CcaSs have the Cys residue (Cys-141 in CcaS) that covalently ligates the chromophore as in plant Phys but not in bacterial Phys (Fig. 6, asterisk). His-184 of CcaS is assumed to form a hydrogen bond with the C19-carbonyl oxygen of ring D in Pg as found in Pr of DrBphP and RpBphP3 (Fig. 6, filled triangle). Three aromatic residues (Tyr-82, Phe-109, and Phe-145 in CcaS) are also conserved as the hydrophobic pocket that encompasses ring D (Fig. 6, open triangles). These facts suggest that Pg of CcaS are practically identical to Pr of Phys with regard to the configuration of ring D and its interaction with the apoprotein.

On the other hand, CcaSs lack the conserved Asp residue in the DIP motif that forms hydrogen bonds with nitrogen atoms of the pyrrole rings A, B, and C via the pyrrole water molecule in Phys (6–8) and is involved in protonation of the chromophore (3, 35) (Fig. 6, boxed type). CcaSs also lack the highly conserved His residue that is positioned next to the chromophore-ligating Cys residue and directly interacts with the pyrrole water from the opposite side of the Asp residue in Phys (Fig. 6, highlighted type). These observations suggest that the environment around rings A, B, and C of CcaS may differ substantially from that of the Phys. We speculate that these differences may cause distortion in the coplanar geometry of rings A, B, and C of PCB, which decouples the π-conjugation system, leading to the blue-shift in the absorption of both forms of CcaS. Alternatively, it might be possible that an unstable second bond shortens the π-conjugation system of the chromophore in the native protein. To gain direct information of the chromophore structure, it is necessary to crystallize CcaS-GAF in both Pg and Pr forms.

We have demonstrated that the Pr form of ΔN-CcaS has higher autophosphorylation activity than Pg. This contrasts with many bacterial and cyanobacterial Phys such as Cph1, where the Pr form shows higher autophosphorylation than Pfr (34). Namely, the Pfr is the active state for CcaS. We also demonstrated that CcaS directly transfers the incorporated phosphate to CcaR. These results suggest that CcaS phosphorylates CcaR under green light, which may change the DNA-binding affinity of CcaR. Phosphorylated CcaR would bind to the promoter region of cpcG2 and activate its transcription (24).

CpcG2 is a unique variant of the rod-core linker polypeptide of phycobilisome, CpcG1. CpcG1 assembles a typical phycobilisome supercomplex (CpcG1-PBS) consisting of central core cylinders and several peripheral rods, whereas CpcG2 contains a hydrophobic segment at the C terminus and forms the atypical phycobilisome CpcG2-PBS consisting of peripheral rods but no central core (25). Fluorescence energy transfer analysis suggested that CpcG2-PBS preferentially transfers light energy to photosystem I, in contrast to the predominant transfer from the typical CpcG1-PBS to photosystem II (26). Considering these previous studies, the green-light-induced expression of cpcG2 can be interpreted as the accumulation of CpcG2-PBS to compensate for the reduced light harvesting by photosystem I chlorophylls because the green light excites PBS more efficiently than chlorophylls. Thus, the chromatic regulation of CpcG2-PBS by CcaS and CcaR enables Synechocystis to coordinate the excitation of the two photosystems to efficiently drive linear electron transport.

The green-light-induced accumulation of phycoerythrin and the red-light-induced accumulation of phycocyanin are typical acclimations found in some cyanobacteria (18). This phenomenon (complementary chromatic adaptation) has been extensively studied in F. diplosiphon. FdRcaE of F. diplosiphon is a putative cyanobacteriochrome that is responsible for expression of the cpc2 operon, which encodes inducible phycocyanin and its associated linkers (21). High sequence similarity in the GAF domain between FdRcaE and SyCcaS suggests that FdRcaE also perceives green or red light reversibly, as does SyCcaS. However, genetic studies have suggested that FdRcaE phosphorylates FdRcaF and FdRcaC under red light and induces expression of cpc2, leading to accumulation of inducible phycocyanin (21). These findings suggest that FdRcaE is a red light receptor that is distinct from the green-light-perceiving SyCcaS and NpCcaS. On the other hand, green-light-induced expression of phycoerythrin genes cpeBA and cpeCDESTR is mainly controlled by yet an unidentified green-light-sensing system (23).

N. punctiforme is an N2-fixing cyanobacterium that accumulates phycoerythrin under green light but not phycocyanin under red light (a phenomenon characteristic of group II chromatic adaptation) (18). Interestingly, rod linker and regulator genes of phycoerythrin (cpeC and cpeR) are clustered with NpccaS and NpccaR in the genome of N. punctiforme, which would support the idea that NpCcaS regulates green-light-induced accumulation of phycoerythrin. It is tempting to speculate that the CcaS ortholog (or another green/red-reversible cyanobacteriochrome) regulates phycoerythrin accumulation in other cyanobacteria including F. diplosiphon.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Media.

The original motile strain of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 was obtained from the Pasteur Culture Collection. A clone showing positive phototaxis (substrain PCC-P) was used for genetic engineering (36). Cells were grown in liquid BG11 medium (37) bubbled with air containing 1% (vol/vol) CO2 at 31°C. E. coli strain JM109 was used for DNA cloning, and E. coli BL21 (DE3) was used for protein expression.

Plasmid Construction.

A compatible plasmid, pKT271, which harbors a heme oxygenase gene, ho1, and a ferredoxin phycocyanobilin oxidoreductase gene, pcyA, of Synechocystis, was used for PCB biosynthesis in E. coli (31). pKT270, which harbors only ho1, was used for biliverdin biosynthesis in E. coli (31). Coding DNAs were amplified by PCR with the following primers: 5′-GGCATATGCGCCAATCTTTAAACTTGG-3′ and 5′-GCTCGAGATCTCATTGCTGGGTGCGTTTTTC-3′ for CcaS-GAF, 5′-GGCATATGCGCCAATCTTTAAACTTGG-3′ and 5′-GCGTCGACATGTTTCTACGCCTA-3′ for ΔN-CcaS, and 5′-TTCATCTCCAGAGACTTC-3′ and 5′-GAGTGAAGCAGAAGTCAC-3′ for CcaR. The cloned PCR products were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing and then excised with NdeI and BamHI. They were subcloned into a pET28a vector (Novagen) for expression in E. coli and into pTCH vector for expression in Synechocystis (15). A plasmid, pKT214, was used for the expression of His-tagged Cph1 (31). In all cases, a polyhistidine tag was fused to the N terminus. Cys141Ala mutant was created by a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Protein Expression and Purification.

Synechocystis cells expressing the His-tagged CcaS-GAF and ΔN-CcaS were grown in 8 liters of BG11 medium with 20 μg·ml−1 chloramphenicol for 10 days and were harvested by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in disruption buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 20 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.5) and stored at −80°C. Cells were thawed on ice and then broken by French press (no. 5501-M, Ohtake) three times at 1,500 kg·cm−2. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and its supernatant was centrifuged again at 146,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto a nickel-affinity His Trap chelating column (GE healthcare). Proteins were eluted by a linear gradient of imidazole.

His-tagged CcaS-GAF was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) carrying pKT271 or pKT270, which was grown in LB containing 0.05 mM 5-aminolevulinic acid, 0.05 mM FeCl3, 20 μg·ml−1 kanamycin, and 20 μg·ml−1 chloramphenicol. When cells were grown at 37°C to OD600 = 0.4–0.8, 10 μM isopropyl thio-β-d-galactoside was added, and cells were incubated at 25°C overnight. His-tagged CcaR was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) as described above without addition of 5-aminolevulinic acid, FeCl3, or isopropyl thio-β-d-galactoside. His-tagged Cph1 was expressed as described (31). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80°C. Cells were thawed in disruption buffer on ice and then broken by French press twice at 1,500 kg·cm−2. The homogenate was centrifuged at 146,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was subjected to nickel-affinity chromatograph as described above.

SDS/PAGE and Zinc-Induced Fluorescence Assay.

Purified proteins were solubilized with 2% lithium dodecyl sulfate, 60 mM DTT, and 60 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) and were subjected to SDS/PAGE on a 15% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel. For the zinc-induced fluorescence assay, the gel was soaked with 20 mM zinc acetate at room temperature for 30 min in the dark, and fluorescence was detected through a 605-nm filter (FMBIO II, Takara Bio) upon excitation at 532 nm. The gel was then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Bio-Rad).

Spectral Analysis.

Absorption spectra were measured at room temperature by using a UV-2400PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). For excitation, light-emitting diodes emitting at 515 nm (E1L53-AG0A, Toyoda Gousei) were used as green light, and light-emitting diodes emitting at 700 nm (L700–03AU, Epitex) were used as red light. For denaturation analysis, each spectral form of CcaS and Cph1 was denatured in 8 M urea (pH 2.0 or 7.5) for a few minutes at room temperature in the dark.

Mass Spectrometry.

In-gel digestion of CcaS-GAF prepared from PCB-producing E. coli with trypsin, isolation of the chromopeptide by HPLC, and mass spectrometric analysis were performed as reported in refs. 14 and 15).

Protein Kinase Assays.

For autophosphorylation, the preirradiated Pg or Pr form of ΔN-CcaS (2 μg) was incubated in a reaction buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 2.5 μM ATP containing 185 kBq of [γ-32P]ATP) at 25°C in the dark. The kinase reaction was stopped by addition of 2% lithium dodecyl sulfate, 60 mM DTT, and 60 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0). For phosphotransfer, 2 μg of ΔN-CcaS was autophosphorylated for 25 min and then incubated with 2 μg of CcaR and unlabeled ATP (final 0.5 mM) for 10 min at 25°C in the dark. Samples were then subjected to SDS/PAGE, and the gel was washed with 45% methanol and 10% acetic acid, dried, and exposed onto an image plate. The intensity of each band was measured with BAS-2500 (Fuji).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Prof. Takayuki Kohchi (Kyoto University) for the gift of pKT271, pKT270, and pKT214. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (to M.I.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in Cyanobase or GenBank [accession nos. sll1473–5, ABI83649 (SyCcaS), slr0473, Q55168 (Cph1), ZP_00106627 (NpCcaS), AAB08575 (FdRcaE), NP_285374 (DrBphP), and NP_948356 (RpBphP3)].

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801826105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Karniol B, Wagner JR, Walker JM, Vierstra RD. Phylogenetic analysis of the phytochrome superfamily reveals distinct microbial subfamilies of photoreceptors. Biochem J. 2005;392:103–116. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lagarias JC, Rapoport H. Chromopeptides from phytochrome – The structure and linkage of the Pr form of the phytochrome chromophore. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:4821–4828. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn J, et al. Probing protein-chromophore interactions in Cph1 phytochrome by mutagenesis. FEBS. 2006;273:1415–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamparter T, et al. The biliverdin chromophore binds covalently to a conserved cysteine residue in the N-terminus of Agrobacterium phytochrome Agp1. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3659–3669. doi: 10.1021/bi035693l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockwell NC, Su YS, Lagarias JC. Phytochrome structure and signaling mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:837–858. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner JR, Brunzelle JS, Forest KT, Vierstra RD. A light-sensing knot revealed by the structure of the chromophore-binding domain of phytochrome. Nature. 2005;438:325–331. doi: 10.1038/nature04118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagner JR, Zhang J, Brunzelle JS, Vierstra RD, Forest KT. High resolution structure of Deinococcus bacteriophytochrome yields new insights into phytochrome architecture and evolution. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12298–12309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang X, Stojkovic EA, Kuk J, Moffat K. Crystal structure of the chromophore binding domain of an unusual bacteriophytochrome, RpBphP3, reveals residues that modulate photoconversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12571–12576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701737104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshihara S, Katayama M, Geng X, Ikeuchi M. Cyanobacterial phytochrome-like PixJ1 holoprotein shows novel reversible photoconversion between blue- and green-absorbing forms. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1729–1737. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kehoe DM, Grossman AR. Similarity of a chromatic adaptation sensor to phytochrome and ethylene receptors. Science. 1996;273:1409–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitz O, Katayama M, Williams SB, Kondo T, Golden SS. CikA, a bacteriophytochrome that resets the cyanobacterial circadian clock. Science. 2000;289:765–768. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilde A, Churin Y, Schubert H, Borner T. Disruption of a Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 gene with partial similarity to phytochrome genes alters growth under changing light qualities. FEBS Lett. 1997;406:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshihara S, Ikeuchi M. Phototactic motility in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:512–518. doi: 10.1039/b402320j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshihara S, et al. Reconstitution of blue-green reversible photoconversion of a cyanobacterial photoreceptor, PixJ1, in phycocyanobilin-producing Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3775–3784. doi: 10.1021/bi051983l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishizuka T, et al. Characterization of cyanobacteriochrome TePixJ from a thermophilic cyanobacterium Thermosynechococcus elongatus strain BP-1. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47:1251–1261. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishizuka T, Narikawa R, Kohchi T, Katayama M, Ikeuchi M. Cyanobacteriochrome TePixJ of Thermosynechococcus elongatus harbors phycoviolobilin as a chromophore. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1385–1390. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman AR, Schaefer MR, Chiang GG, Collier JL. The phycobilisome, a light-harvesting complex responsive to environmental conditions. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:725–749. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.725-749.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tandeau de Marsac N. Occurrence and nature of chromatic adaptation in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1977;130:82–91. doi: 10.1128/jb.130.1.82-91.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjorn GS, Bjorn LO. Photochromic pigments from blue-green algae: Phycochrome-a, phycochrome-b, and phycochrome-c. Physiol Plant. 1976;36:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohki K, Fujita Y. Photoreversible absorption changes of guanidine-HCl-treated phycocyanin and allophycocyanin isolated from the blue-green alga Tolypothrix tenuis. Plant Cell Physiol. 1979;20:483–490. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehoe DM, Gutu A. Responding to color: The regulation of complementary chromatic adaptation. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terauchi K, Montgomery BL, Grossman AR, Lagarias JC, Kehoe DM. RcaE is a complementary chromatic adaptation photoreceptor required for green and red light responsiveness. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:567–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seib LO, Kehoe DM. A turquoise mutant genetically separates expression of genes encoding phycoerythrin and its associated linker peptides. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:962–970. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.962-970.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaytayama M, Ikeuchi M. Perception and transduction of light signals by cyanobacteria. In: Fujiwara M, Sato N, Ishiura S, editors. Frontiers in Life Sciences. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 2006. pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo K, Geng XX, Katayama M, Ikeuchi M. Distinct roles of CpcG1 and CpcG2 in phycobilisome assembly in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Photosynth Res. 2005;84:269–273. doi: 10.1007/s11120-004-7762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondo K, Ochiai Y, Katayama M, Ikeuchi M. The membrane-associated CpcG2-phycobilisome in Synechocystis: A new photosystem I antenna. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1200–1210. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.099267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikeuchi M, Tabata S. Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 – A useful tool in the study of the genetics of cyanobacteria. Photosynth Res. 2001;70:73–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1013887908680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okamoto S, Ikeuchi M, Ohmori M. Experimental analysis of recently transposed insertion sequences in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. DNA Res. 1999;6:265–273. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.5.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christie JM. Phototropin blue-light receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:21–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkelman TR, Lagarias JC. Visualization of bilin-linked peptides and proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1986;156:194–201. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukougawa K, Kanamoto H, Kobayashi T, Yokota A, Kohchi T. Metabolic engineering to produce phytochromes with phytochromobilin, phycocyanobilin, or phycoerythrobilin chromophore in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudiger W, Thummler F, Cmiel E, Schneider S. Chromophore structure of the physiologically active form (P(fr)) of phytochrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6244–6248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.20.6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hubschmann T, Borner T, Hartmann E, Lamparter T. Characterization of the Cph1 holo-phytochrome from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:2055–2063. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh KC, Wu SH, Murphy JT, Lagarias JC. A cyanobacterial phytochrome two-component light sensory system. Science. 1997;277:1505–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Stetten D, et al. Highly conserved residues Asp-197 and His-250 in Agp1 phytochrome control the proton affinity of the chromophore and Pfr formation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2116–2123. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoshihara S, Suzuki F, Fujita H, Geng XX, Ikeuchi M. Novel putative photoreceptor and regulatory genes required for the positive phototactic movement of the unicellular motile cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:1299–1304. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rippka R. Isolation and purification of cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1988;167:3–27. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.