Abstract

Persistent autoantibody production in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) suggests the existence of autoreactive humoral memory, but the frequency of self-reactive memory B cells in SLE has not been determined. Here, we report on the reactivity of 200 monoclonal antibodies from single IgG+ memory B cells of four SLE patients. The overall frequency of polyreactive and HEp-2 self-reactive antibodies in this compartment was similar to controls. We found 15% of IgG memory B cell antibodies highly reactive and specific for SLE-associated extractable nuclear antigens (ENA) Ro52 and La in one patient with serum autoantibody titers of the same specificity but not in the other three patients or healthy individuals. The germ-line forms of the ENA antibodies were non-self-reactive or polyreactive with low binding to Ro52, supporting the idea that somatic mutations contributed to autoantibody specificity and reactivity. Heterogeneity in the frequency of memory B cells expressing SLE-associated autoantibodies suggests that this variable may be important in the outcome of therapies that ablate this compartment.

Keywords: autoimmunity, B cell, repertoire, self-tolerance

Humoral memory for foreign antigens is essential for long-term protection against invading pathogens (1–3). However, autoreactive memory cells may have life-threatening consequences in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a disease associated with a breakdown in B cell tolerance and elevated serum levels of high-affinity IgG autoantibodies (4–6).

In addition to altered tolerance in IgG-producing B cells, individuals with SLE show abnormalities in early B cell tolerance checkpoints, leading to increased numbers of autoreactive mature naïve B cells independent of disease activity (7, 8). Naïve B cells do not secrete antibodies, but antigen-mediated activation induces their differentiation into antibody-secreting short-lived plasmablasts and long-lived plasma cells or memory B cells (2, 3, 9, 10). Thus, the finding that high frequencies of autoreactive naïve B cells are present in SLE suggests that these cells might be the precursors of high-affinity IgG+ B cells contributing to humoral autoimmunity in SLE (7, 8). Alternatively, defects that lead to abnormalities in memory B cell tolerance in SLE might be independent of the earlier tolerance defects (7, 8).

IgG antibodies are produced primarily by long-lived plasma cells that reside in the bone marrow (10). Plasma cells are generated from naïve B cells during primary responses or from reactivated memory B cells, which circulate in the blood of normal individuals and patients with SLE (2, 3, 9–13). Despite the importance of IgG-expressing memory B cells in producing pathogenic antibodies in SLE, the frequency of such cells and the antigen-binding characteristics of their antibodies are not known. Here, we report on the molecular features and antigen-binding properties of 200 monoclonal antibodies cloned from IgG+ memory B cells from four SLE patients with active disease.

Results

Features of IgG Antibodies Cloned from SLE Memory B Cells.

We studied four newly diagnosed, untreated, pediatric SLE patients (169, 174, 175, and 176) with active disease [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. The patients' clinical diagnostic features at first presentation were diverse as were the serum autoantibody specificities reflecting the heterogeneity of SLE symptoms (Table S1). All patients were anti-nuclear antibody (ANA)-positive but showed different serology with antibodies against dsDNA, cardiolipin, Sm, ribonucleoproteins (RNP), and other ENAs. Two patients showed lupus nephritis (Table S1).

To characterize the IgG antibodies expressed by memory B cells in SLE, we isolated memory B cells (CD19+CD27+IgG+CD38−) from peripheral blood [Fig. S1; (13)]. B cells from all four SLE patients showed increased IgG staining not observed in any of the healthy controls (HC) [Fig. S1; (13)]. Increased numbers of CD38+CD27++ plasmablasts with low levels of surface IgG have been reported in some patients with active disease (14–16), but were found only in SLE169 (Fig. S1). Comparison of antibodies cloned from purified plasmablasts and memory B cells from this patient showed no significant differences in any of our reactivity assays and therefore these were considered together (Fig. S1 and Table S2). Nucleotide sequence analyses showed that all antibodies were unique, and none were clonally related (Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5). Therefore, strong clonal dominance was not a feature of IgG+ memory B cells in SLE.

The molecular features of IgG memory B cell antibodies varied among individual patients, but we found that the majority of functional Ig genes were expressed in SLE [Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5; (17–20)]. No consistent significant differences in Ig heavy (IgH) variable (V), diversity (D), or joining (J) gene usage or IgH complementary determining region (CDR) 3 aa length or positive charges were observed between patients and HC [Fig. 1 and Figs. S2 and S3; (7, 8, 21)].

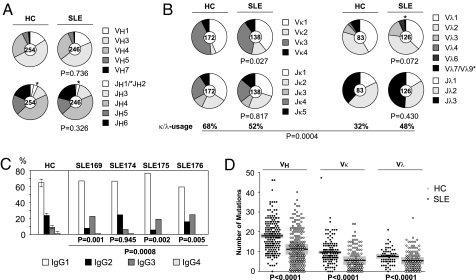

Fig. 1.

IgH and IgL chain gene features from IgG memory B cell antibodies of SLE patients and HC. Ig gene repertoire and Ig gene features of IgG memory B cell antibodies cloned from three published (24) and one unpublished HC (JH) and four patients with SLE (169, 174, 175, and 176). P values compare data from the patients to the HC. (A) Pie charts depict VH and JH gene usage. The absolute number of sequences analyzed is indicated in the center of each pie chart. (B) Pie charts depict Vκ/Jκ (Left) and Vλ/Jλ gene usage (Right). The absolute number of sequences analyzed is indicated in the center of each pie chart. The frequency of Igκ- and Igλ-positive antibodies is indicated. (C) Bar graphs show IgG1 (white), IgG2 (black), IgG3 (dark gray), and IgG4 (light gray) subclass usage. (D) The absolute number of mutations (nucleotide exchanges as compared with germ line) in individual VH, Vκ, and Vλ genes (FWR1 - FWR3) of antibodies from IgG+ memory B cells of four healthy HC (filled circles) and four SLE patients (open circles) is shown. Horizontal lines represent the average number of mutations and gray bars represent the standard deviation.

Igκ light chain usage was significantly different from normal in that memory B cell antibodies from SLE patients showed an increased usage of Vκ2 family genes as reported [P = 0.027; Figs. 1, Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5; (18)]. Analysis of individual Vκ genes consistently showed a low level of Vκ3-20 usage in all four patients as compared with HC (Fig. S3B). SLE patients also consistently expressed Igλ light chains more frequently than HC (average 48% in SLE vs. 32% in healthy, P = 0.0004; Fig. 1B and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5, and Table S6). When individual patients were compared with HC, SLE169 showed a number of unusual Ig gene features with long IgH CDR3 regions (average 15.1 aa vs. 13.9 aa in healthy, P = 0.012), increased VH4-4 gene usage, low frequency of Vλ2 family genes, and increased Vλ3 gene family usage. IgG+ memory B cells from this patient were also abnormal in that >25% of the B cells expressed a functional Igκ and Igλ light-chain transcript as compared with 0% in HC and 0–2% in the other SLE patients [Fig. S3 and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5, Table S6, and Table S7; (21, 22)].

Three of the four patients (SLE169, SLE175, and SLE176) showed alterations in the IgG subclass distribution of memory antibodies with a bias toward IgG1 and IgG3 and reduced frequency of IgG2 (Fig. 1C; Table S2, Table S4, and Table S5). Only SLE174 showed a normal subclass distribution dominated by IgG1 and IgG2 and with low numbers of IgG3- and IgG4-expressing memory cells (Fig. 1C and Table S3).

In contrast to previous reports (21, 23), analysis of somatic hypermutations (SHM) revealed significantly reduced levels in IgH and Ig light (IgL) chain V region genes (VH, Vκ, and Vλ) cloned from SLE patients (P < 0.0001 for VH, P < 0.0001 for Vκ, and P < 0.0001 for Vλ; Fig. 1D, Fig. S4A, and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5). However, low V gene SHM frequencies in SLE were not associated with alterations in the ratio of V gene replacement (R) to silent (S) SHM in framework regions (FWR) or CDRs (Fig. S4B) and did not correlate directly with the patients' ages. For example, the youngest patient, SLE175, showed the highest average number of V gene SHM of all (Fig. S4A), and the average number of VH gene SHM was lower in SLE174 than in the age-matched HC PN (10.5 vs. 17.0). In HC and SLE patients, SHM frequencies were higher in VH than in VL genes as noted by others (17, 18). Strikingly, antibodies from SLE169 were different from antibodies of the other patients (P = 0.005) and HC (P = 0.0001) in that the ratio of IgH to IgL V gene SHM was significantly increased (4.6 as compared with 2.4–2.7 in SLE and 2.3–3.0 in HC; Fig. S4C), and mutated IgH chains associated with unmutated IgL chains were more frequently detected than in the other patients or HC [Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5, and Table S6; (24)].

In summary, antibodies cloned from SLE IgG+ memory B cells consistently showed altered IgVκ2 gene family and IgVκ3–20 usage, an overall increase in Igλ light-chain usage and low levels of SHM, whereas abnormalities in V region features such as IgH CDR3 length, IgVλ usage, and IgG subclass distribution were variable among patients.

Polyreactive and Self-Reactive IgG Memory B Cell Antibodies in SLE.

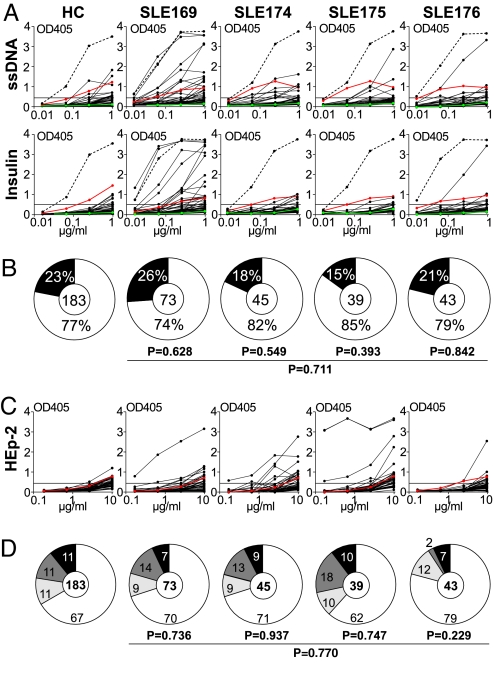

In healthy humans, substantial numbers of circulating IgG+ memory B cells express polyreactive and self-reactive antibodies (24, 25). To determine the frequency of polyreactive antibodies expressed by IgG+ memory B cells from SLE patients, we tested all antibodies for reactivity with ssDNA, dsDNA, insulin, and LPS (Fig. 2A, Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5, and data not shown). Antibodies with reactivity against at least two of these structurally diverse self-and nonself antigens were considered polyreactive (26, 27). Polyreactive IgG memory B cell antibodies were found in all of the patients, but the frequency of such cells was not significantly different from HC [26% SLE169, 18% SLE174, 15% SLE175, and 21% SLE176 as compared with 23% for four HC; Fig. 2B and Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5, and Table S6; (24)], and most of these antibodies showed only low levels of polyreactivity. A small number of highly polyreactive antibodies were observed in SLE169 but in none of the other patients (Fig. 2A). We conclude that the frequency of polyreactive IgG memory B cell antibodies in SLE was not significantly different from HC (23% in healthy vs. 22% in SLE, P = 0.711; Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Polyreactivity and self-reactivity of IgG memory B cell antibodies from SLE patients. (A) IgG memory B cell antibodies from HC JH and SLE patients were tested for polyreactivity with ssDNA, dsDNA, insulin, and LPS by ELISA. Representative ELISA graphs for reactivity with ssDNA and insulin are shown. Dotted lines represent the high positive control antibody ED38 (61). Horizontal lines show cut-off OD405 for positive reactivity. Green and red lines show the negative control antibody mGO53 and low positive control antibody eiJB40, respectively (26). (B) Pie charts summarize the frequency of polyreactive (black) and nonpolyreactive (white) IgG+ memory B cell clones from four HC and SLE patients (24). The number of tested antibodies is indicated in the pie chart center. P values are compared with four HC (24). (C) IgG memory B cell antibodies from HC JH and patients with SLE were tested for self-reactivity by HEp-2 cell ELISA. The horizontal line shows ELISA cut-off OD405 for positive reactivity, and the red line shows low positive control serum. (D) Pie charts summarize the frequency of self-reactive IgG memory B cell antibodies from HC and SLE patients with nuclear (black), nuclear plus cytoplasmic (dark gray), and cytoplasmic (light gray) HEp-2 cell IFA staining patterns and the frequency of nonreactive antibodies (white). The number of tested antibodies is indicated in each pie chart center. P values are compared with IgG memory B cell antibodies from four HC (24).

ELISA with HEp-2 cell lysates and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with HEp-2 cells are used clinically to detect ANAs, which are hallmark features of SLE. To determine the frequency of ANAs produced by IgG+ memory B cells in SLE, we tested all 200 recombinant antibodies by HEp-2 cell ELISA (Fig. 2C) and IFA (data not shown). Surprisingly, we found no difference in the frequency of self-reactive IgG+ memory B cells between HC and SLE patients (on average 33% in HC vs. 30% in SLE; Fig. 2D). SLE memory B cell antibodies were also indistinguishable from control antibodies showing diverse nuclear and cytoplasmic IFA staining patterns [P = 0.770, Fig. 2D, and data not shown; (24)].

IgG+ Memory B Cells Producing Anti-Ro and Anti-La Antibodies.

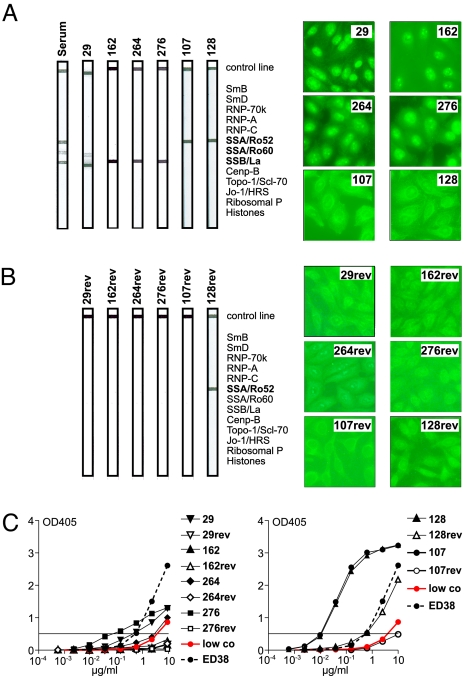

To determine whether any of the cloned SLE antibodies showed specificity for SLE-associated autoantigens, we tested them in line immunoassays (LIA) in which reactivity to 13 purified SLE antigens is tested on a membrane (Fig. 3). Of 200 SLE antibodies tested, 6 showed specific reactivity in this assay, and no reactive clones were found among 84 IgG memory B cell antibodies from HC [Fig. 3A and data not shown; (24)]. All of the reactive antibodies were from patient SLE175, who also showed serologic reactivity to Ro/SSA and La/SSB in this assay, and none of the antibodies were clonally related (Fig. 3A and Table S4). Two of the antibodies (107 and 128) showed specificity for Ro52, whereas the other four antibodies were reactive with La (29, 162, 264, 276) and one of the anti-La antibodies also showed low levels of cross-reactivity with Ro60 (29) (Fig. 3A). Although our patients' serum displayed reactivity against dsDNA, RNP, or Sm, we did not find any specific antibodies to these antigens among the 200 tested (Fig. 3 and Table S1, Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, and Table S5). In summary, we found a high frequency of IgG+ memory B cells producing SLE antibodies (6 of 39, 15%) in one of the four patients (Figs. 2 and 3 and data not shown), and these antibodies reflected the specificity of serum autoantibodies measured in this patient (Fig. 3A and Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Ro52/SSA-reactive and La/SSB-reactive SLE IgG memory B cell antibodies. (A) LIA with 13 SLE-associated autoantigens (SmB, SmD, RNP-70k, RNP-A, RNP-C, Ro52/SSA, Ro60/SSA, La/SSB, Cenp-B, Topo-1/Scl-70, Jo-1/HRS, Ribosomal P, Histones) identified four La/SSB-reactive (29, 162, 264, and 276) and two Ro52/SSA-reactive (107 and 128) antibodies among 200 tested IgG memory B cell antibodies from SLE patients and 84 tested IgG memory B cell antibodies from HC. Anti-Ro52/SSB and anti-La/SSB antibodies were all from SLE175. LIA result obtained with serum from the same patient is shown for comparison. HEp-2 cell IFA staining patterns of the same antibodies are shown. (B) Germ-line versions of the two anti-Ro52/SSA and four anti-La/SSB reactive IgG memory B cell antibodies from SLE175 were tested by LIA and IFA as in A. (C) HEp-2 ELISA results of recombinant mutated (filled symbols) anti-La/SSB (29, 162, 264, 276; Left) and anti-Ro52/SSA (107, 128; Right) antibodies and their germ-line counterparts (open symbols). Red lines in the ELISA graphs represent low positive control serum, dotted lines represent ED38 (61), and horizontal lines show cut-off OD405 for positive reactivity.

The anti-Ro52 and anti-La autoantibodies were encoded by unique Igγ1 heavy-chain and Igκ light-chain genes, and the number of SHM was above average compared with all other IgG memory B cell antibodies from SLE175 (Table S4; P = 0.003). To determine whether anti-Ro52 and anti-La reactivity was due to SHM, we reverted the IgH and IgL chain genes of the six anti-Ro52 and anti-La antibodies to their germ-line form and compared mutated and unmutated antibodies by HEp-2 cell ELISA, IFA, and LIA (Fig. 3). In the absence of SHM, 5 of 6 antibodies lacked immunoblot and HEp-2 cell reactivity or reactivity with Ro52 or La in ELISA (107rev, 29rev, 162rev, 264rev, 276rev; Fig. 3 B and C and data not shown). Only one of the germ-line antibodies, 128rev, retained a low level of HEp-2 cell reactivity in the ELISA and IFA, and the same antibody was also reactive with Ro52 in the LIA (Fig. 3 B and C) and in ELISA with purified Ro52 (data not shown). We conclude that high levels of reactivity with Ro52 and La in IgG memory B cell antibodies from SLE175 developed as a result of SHM.

A role for SHM in the generation of polyreactive and self-reactive antibodies was confirmed when the germ-line forms of the 6 Ro52 and La reactive antibodies and 21 randomly selected SLE IgG+ memory B cell antibodies were tested for polyreactivity and self-reactivity by ELISA and IFA [Fig. S5 and Table S8; (27–29)]. The majority of mutated polyreactive and self-reactive antibodies lost reactivity in the germ-line form. Only a few antibodies showed self- or polyreactivity independent of SHM, including 128rev with specificity for Ro52 in the mutated form. The germ-line form of all other Ro52 and La reactive antibodies lacked polyreactivity (Fig. S5 and Table S8). In summary, the data suggest that naïve B cells that produce self-reactive or polyreactive antibodies can enter the germinal center in SLE but that most self-reactive IgG memory B cell antibodies including anti-Ro52 and anti-La antibodies develop from nonreactive precursors by SHM.

Discussion

Abnormalities in the IgH and IgL chain gene repertoire have been reported in SLE (7, 8, 21, 23, 30–33), and our analysis confirms the high degree of variability in Ig gene features and usage. All four patients showed a relative increase in Igλ light-chain usage suggestive of increased levels of receptor editing (34–36). One patient showed a high frequency of Igκ+Igλ+ double positive cells, which is also associated with extensive receptor editing (37–41). The finding that this patient showed an unusually high ratio of VH to VL gene mutations may indicate that the IgL chain replacement occurred late, possibly after antigen-mediated stimulation and the onset of SHM. However, it is important to note that this was not observed in the other patients and may thus be a unique feature of the disease in this patient.

In mice, isotypic and allotypic inclusion can silence autoantibodies by diluting out autoreactivity and thereby allow B cells that produce self-reactive antibodies to pass the central self-tolerance checkpoint and to participate in immune response (37–39, 42–45). Double producing B cells were rare in the IgG+ memory pool of the other SLE patients and were not enriched in naïve B cells from SLE patients with active disease (7, 8). Thus, isotypic inclusion is not a general feature of this disease but may be characteristic of a subgroup of SLE patients. We found a low frequency of Vk3-20 usage in SLE IgG+ memory B cells. Similarly, mature naïve B cells from untreated active SLE patients showed a lower frequency of Vk3-20 usage than HC [13.5% vs. 19.6%; (8, 26, 46)], but this did not reach statistical significance. Thus, it remains to be determined whether low levels of Vk3-20 usage in IgG+ memory B cells reflects a general deficit in Vk3-20 selection or alterations in V(D)J recombination (47). Whether the overall low Igκ/Igλ light-chain ratio in our cohort of SLE patients reflects increased secondary IgL chain gene recombination during the early stages of B cell development in the bone marrow or peripheral selection cannot be addressed directly. However, the finding that Igλ usage in naïve B cells from patients with active SLE was not significantly different from healthy would argue in favor of selection or late receptor editing (8). IgG+ memory B cells from SLE patients showed overall low numbers of IgH and IgL chain SHM but normal V gene R/S ratios, suggesting that selection of activated B cells is not grossly affected. Others have reported an increase in Ig mutational frequency in peripheral CD19+ B cells in SLE (23, 48), but these findings were not confirmed in a recent study on circulating IgG+ B cells, where, in fact, the SHM frequency was found to be slightly lower in patients as compared with HC (18).

The frequency of self-reactive and ANAs or polyreactive antibodies in CD27+IgG+ memory B cells in patients with SLE was similar to that found in normal individuals (24). Thus, autoreactive IgG memory B cell antibodies in SLE can arise from either polyreactive or nonreactive precursors by SHM just as they do in normal individuals (24). Reactivity to DNA is associated with positively charged amino acid residues (49), and polyreactivity in newly generated B cells is associated with long and charged IgH CDR3 regions, but the rules that govern how SHMs influence polyreactivity remain to be determined (26). It is unlikely that binding to structurally diverse antigens such as insulin, LPS, and DNA can be attributed to recognition of shared epitopes, because it may be the case for binding to structurally similar antigens such as ssDNA and dsDNA.

Because of a defect in early self-tolerance checkpoints, patients with SLE show high numbers of circulating self-reactive and polyreactive mature naïve B cells (7, 8), and these cells can be recruited into germinal center reactions and contribute to the formation of autoreactive plasma cells and memory B cells. However, the normal frequency of self- and polyreactive IgG+ memory B cells in SLE suggests that the increased number of self-reactive naïve B cells does not have a strong impact on the general level of autoreactivity in the IgG+ memory B cell pool. Thus, the defects that lead to abnormalities in IgG+ memory B cell tolerance in SLE may be independent of the earlier defects in tolerance. We did not observe signs of clonal expansion in the IgG+ memory B cell compartment of SLE patients, and Ro52 and La reactive antibodies from SLE175 were not clonally related. However, the number of cells analyzed may have been too small to detect low levels of clonal expansion in IgG+ memory B cells. In wild-type and FcγRIIB-deficient SLE mice, clonal expansion contributes significantly to the antigen-experienced B cell repertoire (T.T. and H.W., unpublished observation), suggesting that the human antibody repertoire may be more diverse than its murine counterpart.

IgG autoantibodies with high levels of reactivity for SLE autoantigens Ro52 and La were identified only in SLE175, but these antibodies made up a substantial fraction of the circulating IgG+ memory B cell pool in this patient. Similar to low-level self- and polyreactive antibodies from HC and SLE patients, antibodies with strong autoreactivity for Ro52 and La originated from naïve cells that had low levels of binding for this antigen and were either polyreactive or nonreactive. These observations are consistent with previous analyses showing that anti-DNA autoantibodies from SLE patients and mice are products of SHM and selection (50–53). Because of the relatively small number of antibodies cloned from each patient, it is not possible to determine whether highly autoreactive memory B cells were infrequent or simply not circulating in the bloodstream of these patients. In addition, responses to certain self-antigens such as DNA may differ from others like anti-Ro, as evidenced by their discrete responses to B cell depletion therapy (54, 55). Anti-DNA antibodies are rapidly depleted from serum after such therapy, whereas anti-Ro was not (54, 55). Last, normal individual variation may further contribute to the differences observed among the patients.

The relative contribution of IgG+ memory B cells to the production of serum autoantibodies in SLE is not known, but memory B cells readily respond to activation by differentiation into antibody-secreting B cells (11, 13, 56, 57). Indirect evidence for a role of memory B cells in human autoimmune diseases comes from clinical studies with rituximab, a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that efficiently depletes all circulating B cells. Recent evidence suggests that relapses after anti-CD20 therapy are strongly associated with the reappearance of high numbers of circulating memory B cells (54, 58–60). However, it is not yet clear whether this reflects early regeneration of such cells or efflux of nondepleted memory B cells from secondary lymphoid organs (54, 55, 58, 59).

In summary, our data demonstrate that autoreactive IgG+ memory B cells are generated at high frequency in some, but not all, patients with SLE. Whether the presence of higher numbers of such B cells might correlate with clinical outcome in response to B cell ablative therapy remains to be determined.

Materials and Methods

Single B Cell Sorting.

All samples were obtained after signed informed consent in accordance with institutional review board-reviewed protocols at The Rockefeller University. The experiments were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Control data from IgG+ memory B cells of three HC were published and are shown for comparison (24). Single CD19+CD38−CD27+IgG+ memory B cells and CD19+CD38+CD27+IgG+ plasmablasts were isolated as described (26) after B cell enrichment with RosetteSep (StemCell Technologies) and staining with anti-CD19-APC, anti-CD38-PE, anti-CD27-FITC, anti-IgG-Biotin (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), and Streptavidin-PECy7 (Caltag).

PCR Amplification and Expression-Vector Cloning and Mutation Analysis.

Single-cell cDNA synthesis was performed as described by using SuperScript III at 50°C (26, 27). Igγ and Igk and λ chain genes were amplified in two rounds of nested PCR. All PCR products were sequenced and analyzed for Ig gene usage and CDR3 analysis, number of V gene SHM (Ig-Blast; Table S2, Table S3, Table S4, Table S5, and Table S6), and for IgG isotype subclass (http://imgt.cines.fr). For the analysis of replacement (R) and silent (S) mutations, each nucleotide was considered independently except in rare events where a combination of nucleotide exchanges within one codon was needed to replace or retain a specific amino acid. R and S frequencies and R/S ratios in FWRs and CDRs were calculated for each region based on the absolute number of nucleotides in all analyzed sequences as defined by Ig-Blast. Second PCR products for Igλ genes contained restriction sites allowing direct cloning into expression vectors. For Igγ and Igk genes, restriction sites for expression vector cloning were introduced after sequencing by using gene-specific primers and first PCR products as template. All IgH and IgL chain genes were sequenced after cloning to confirm identity with the original PCR products.

Antibody Production, ELISA, Line Immunoassay, and Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay.

Antibodies were expressed and tested for polyreactivity with ds/ssDNA, insulin, and LPS and for self-reactivity with HEp-2 cells by ELISA and IFA as described (26). Threshold values for reactivity are indicated in the graphs and were set in all assays by using our published control antibodies mGO53 (negative), eiJB40 (low positive), and ED38 (high positive) for polyreactivity ELISAs and additional positive and negative control sera for HEp-2 reactivity (26, 61). Data shown are representative for at least three independent experiments. LIA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (INNO-LIA; Immunogenetics). In brief, strips were incubated with 2 μg/ml antibody solution or 1:100-diluted serum, followed by two wash steps. Bound antibodies were detected by using anti-human IgG coupled to alkaline phosphatase and BCIP/NBT as substrate. Internal positive controls on each blot strip and cut-off controls were included and were used as reference points to determine positive reactivity.

Reversion of Hypermutated Sequences to Germ Line.

Antibodies for reversion experiments are listed in Table S8 and include antibodies from SLE175 with specificity for Ro52/SSA (107, 128) and La/SSB (29, 162, 264, and 276) and 21 randomly chosen clones (20 with known D genes and 1 with short N-nucleotide regions in IgH CDR3). Mutated IgH and IgL chain genes were reverted to their germ-line sequence by two separate PCRs for the V gene and the (D)J gene, followed by a third overlap PCR to fuse the two PCR products as described (24, 27–29). All reverted IgH and IgL chain PCR products were sequenced before and after cloning to confirm lack of mutations. Recombinant mutated and unmutated antibodies were expressed and tested for polyreactivity and self-reactivity as described above.

Statistics.

P values for Ig gene repertoire analyses, analysis of positive charges in IgH CDR3, and antibody reactivity were calculated by 2 × 2 or 2 × 5 Fisher's Exact test or χ2 test. P values for IgH CDR3 length and V gene FWR1-FWR3 mutations were calculated by nonpaired two-tailed Student's t test. P values for ratios of VH to VL gene SHM were calculated by one-way ANOVA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Marie Wahren-Herlenius (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden) for reagents, Jens Hellwage and Sergey Yurasov for technical assistance, and all members of the H.W. and M.C.N. laboratory for discussion. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to M.C.N.), the Dana Foundation (to H.W.), the German Research Foundation (to H.W.), and the Naito Foundation (to M.T.). M.C.N. is a Howard Hughes Medical Investigator, and B.M. is supported by the International Max Planck Research School for Infectious Diseases and Immunology Program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0803644105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1903–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed R, Gray D. Immunological memory and protective immunity: Understanding their relation. Science. 1996;272:54–60. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson A, Diamond B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:340–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotzin BL. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell. 1996;85:303–306. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherer Y, Gorstein A, Fritzler MJ, Shoenfeld Y. Autoantibody explosion in systemic lupus erythematosus: More than 100 different antibodies found in SLE patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34:501–537. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurasov S, et al. Persistent expression of autoantibodies in SLE patients in remission. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2255–2261. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yurasov S, et al. Defective B cell tolerance checkpoints in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:703–711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLennan IC. Germinal centers. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:117–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radbruch A, et al. Competence and competition: The challenge of becoming a long-lived plasma cell. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:741–750. doi: 10.1038/nri1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruyama M, Lam KP, Rajewsky K. Memory B-cell persistence is independent of persisting immunizing antigen. Nature. 2000;407:636–642. doi: 10.1038/35036600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangye SG, Good KL. Human IgM+CD27+ B cells: memory B cells or “memory” B cells? J Immunol. 2007;179:13–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arce E, et al. Increased frequency of pre-germinal center B cells and plasma cell precursors in the blood of children with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;167:2361–2369. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odendahl M, et al. Disturbed peripheral B lymphocyte homeostasis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2000;165:5970–5979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vallerskog T, et al. Treatment with rituximab affects both the cellular and the humoral arm of the immune system in patients with SLE. Clin Immunol. 2007;122:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Wildt RM, Hoet RM, van Venrooij WJ, Tomlinson IM, Winter G. Analysis of heavy and light chain pairings indicates that receptor editing shapes the human antibody repertoire. J Mol Biol. 1999;285:895–901. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wildt RM, Tomlinson IM, van Venrooij WJ, Winter G, Hoet RM. Comparable heavy and light chain pairings in normal and systemic lupus erythematosus IgG(+) B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:254–261. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<254::AID-IMMU254>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorner T, Lipsky PE. Molecular basis of immunoglobulin variable region gene usage in systemic autoimmunity. Clin Exp Med. 2005;4:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10238-004-0051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefranc MP, et al. IMGT-Choreography for immunogenetics and immunoinformatics. In Silico Biol. 2005;5:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dorner T, Lipsky PE. Immunoglobulin variable-region gene usage in systemic autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2715–2727. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2715::aid-art458>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giachino C, Padovan E, Lanzavecchia A. Kappa+lambda+ dual receptor B cells are present in the human peripheral repertoire. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1245–1250. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorner T, Heimbacher C, Farner NL, Lipsky PE. Enhanced mutational activity of Vkappa gene rearrangements in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:188–196. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiller T, et al. Autoreactivity in human IgG(+) memory B cells. Immunity. 2007;26:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koelsch K, et al. Mature B cells class switched to IgD are autoreactive in healthy individuals. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1558–1565. doi: 10.1172/JCI27628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wardemann H, et al. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiller T, et al. Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herve M, et al. Unmutated and mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia derive from self-reactive B cell precursors despite expressing different antibody reactivity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1636–1643. doi: 10.1172/JCI24387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuiji M, et al. A checkpoint for autoreactivity in human IgM+ memory B cell development. J Exp Med. 2006;203:393–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bensimon C, Chastagner P, Zouali M. Human lupus anti-DNA autoantibodies undergo essentially primary V kappa gene rearrangements. EMBO J. 1994;13:2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manheimer-Lory AJ, Zandman-Goddard G, Davidson A, Aranow C, Diamond B. Lupus-specific antibodies reveal an altered pattern of somatic mutation. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2538–2546. doi: 10.1172/JCI119796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh-Bernard AE, et al. Regulation of inherently autoreactive VH4–34 B cells in the maintenance of human B cell tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1061–1070. doi: 10.1172/JCI12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suzuki N, Harada T, Mihara S, Sakane T. Characterization of a germline Vk gene encoding cationic anti-DNA antibody and role of receptor editing for development of the autoantibody in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1843–1850. doi: 10.1172/JCI118985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gay D, Saunders T, Camper S, Weigert M. Receptor editing: An approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J Exp Med. 1993;177:999–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Retter MW, Nemazee D. Receptor editing occurs frequently during normal B cell development. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1231–1238. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiegs SL, Russell DM, Nemazee D. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1009–1020. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Louzoun Y, Weigert M. Editing anti-DNA B cells by Vlambdax. J Exp Med. 2004;199:337–346. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witsch EJ, Cao H, Fukuyama H, Weigert M. Light chain editing generates polyreactive antibodies in chronic graft-versus-host reaction. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1761–1772. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casellas R, et al. Igkappa allelic inclusion is a consequence of receptor editing. J Exp Med. 2007;204:153–160. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y, Li H, Weigert M. Autoreactive B cells in the marginal zone that express dual receptors. J Exp Med. 2002;195:181–188. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelanda R, Torres RM. Receptor editing for better or for worse. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doyle CM, Han J, Weigert MG, Prak ET. Consequences of receptor editing at the lambda locus: Multireactivity and light chain secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11264–11269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerdes T, Wabl M. Autoreactivity and allelic inclusion in a B cell nuclear transfer mouse. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1282–1287. doi: 10.1038/ni1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu S, et al. Receptor editing can lead to allelic inclusion and development of B cells that retain antibodies reacting with high avidity autoantigens. J Immunol. 2005;175:5067–5076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Velez MG, et al. Ig allotypic inclusion does not prevent B cell development or response. J Immunol. 2007;179:1049–1057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herve M, et al. CD40 ligand and MHC class II expression are essential for human peripheral B cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foster SJ, Brezinschek HP, Brezinschek RI, Lipsky PE. Molecular mechanisms and selective influences that shape the kappa gene repertoire of IgM+ B cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1614–1627. doi: 10.1172/JCI119324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobi AM, Hansen A, Burmester GR, Dorner T, Lipsky PE. Enhanced mutational activity and disturbed selection of mutations in V(H) gene rearrangements in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2000;33:61–76. doi: 10.3109/08916930108994110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radic MZ, et al. Residues that mediate DNA binding of autoimmune antibodies. J Immunol. 1993;150:4966–4977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cocca BA, et al. Structural basis for autoantibody recognition of phosphatidylserine-beta 2 glycoprotein I and apoptotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13826–13831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241510698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, et al. Regulation of anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies. Immunity. 2003;18:185–192. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radic MZ, Weigert M. Genetic and structural evidence for antigen selection of anti-DNA antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:487–520. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wellmann U, et al. The evolution of human anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9258–9263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500132102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leandro MJ, Cambridge G, Edwards JC, Ehrenstein MR, Isenberg DA. B-cell depletion in the treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A longitudinal analysis of 24 patients. Rheumatology. 2005;44:1542–1545. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng KP, et al. B cell depletion therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus: Long-term follow-up and predictors of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1259–1262. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.067124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arpin C, Banchereau J, Liu YJ. Memory B cells are biased towards terminal differentiation: A strategy that may prevent repertoire freezing. J Exp Med. 1997;186:931–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lanzavecchia A, et al. Understanding and making use of human memory B cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anolik JH, et al. Delayed memory B cell recovery in peripheral blood and lymphoid tissue in systemic lupus erythematosus after B cell depletion therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3044–3056. doi: 10.1002/art.22810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leandro MJ, Cambridge G, Ehrenstein MR, Edwards JC. Reconstitution of peripheral blood B cells after depletion with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:613–620. doi: 10.1002/art.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edwards JC, et al. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–2581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meffre E, et al. Surrogate light chain expressing human peripheral B Cells produce self-reactive antibodies. J Exp Med. 2004;199:145–150. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.