Summary

The spliceosome is the huge macromolecular assembly responsible for the removal of introns from pre-mRNA transcripts. The size and complexity of this dynamic cellular machine dictates that structural analysis of the spliceosome is best served by a combination of techniques. Electron microscopy is providing a more global, albeit less detailed, view of spliceosome assemblies. X-ray crystallographers and NMR spectroscopists are steadily reporting more atomic resolution structures of individual spliceosome components and fragments. Increasingly, structures of these individual pieces in complex with binding partners are yielding insights into the interfaces that hold the entire spliceosome assembly together. Although the information arising from the various structural studies of splicing machinery has not yet fully converged into a complete model, we can expect that a detailed understanding of spliceosome structure will arise at the juncture of structural and computational modeling methods.

Introduction

Pre-mRNA splicing is a critical step in eukaryotic gene expression. In human cells, over 90% of genes contain introns that must be removed from transcripts in order to produce functional messenger RNAs. Moreover, with the limited number of genes present in the human genome, regulation of splice site choice is a key means to expanding the functionality of the proteome. The spliceosome is the nuclear machinery responsible for pre-mRNA splicing. This large complex, composed of over 150 individual proteins and 5 U-rich small nuclear RNAs (U snRNAs), may indeed deserve the moniker “the most complicated macromolecular machine in the cell [1]”. Beyond its size, the spliceosome is also highly dynamic, and the prevailing model is that the spliceosome is assembled from its five constituent U snRNPs and other components for each splicing event and then disassembled prior to the next round of splicing. This so-called “splicing cycle” is characterized by a series of intermediate splicing complexes that are in large part defined by the identity of the associated U snRNPs and the state of the pre-mRNA substrate in terms of the two-step chemical splicing reaction [2]. The transitions between the intermediate splicing complexes are also characterized by extensive remodeling of RNA:RNA and RNA:protein interactions within and between the U snRNPs and pre-mRNA [3]. It is very likely that additional spliceosome conformational states remain to be characterized. Given the dynamic complexity of the spliceosome, detailed structure-function analyses of the complex present an extreme challenge to structural biologists. However, steady progress in visualizing the architecture of this behemoth machine and its components continues to be reported, and this review provides a synopsis of splicing-related structures determined in the last two years. An atomic view of the entire spliceosome could be years away, but in the interim lower resolution models of intermediate splicing complexes and high-resolution structures of smaller key bits are providing insights into this macromolecular assembly extraordinaire.

A global view of splicing complexes

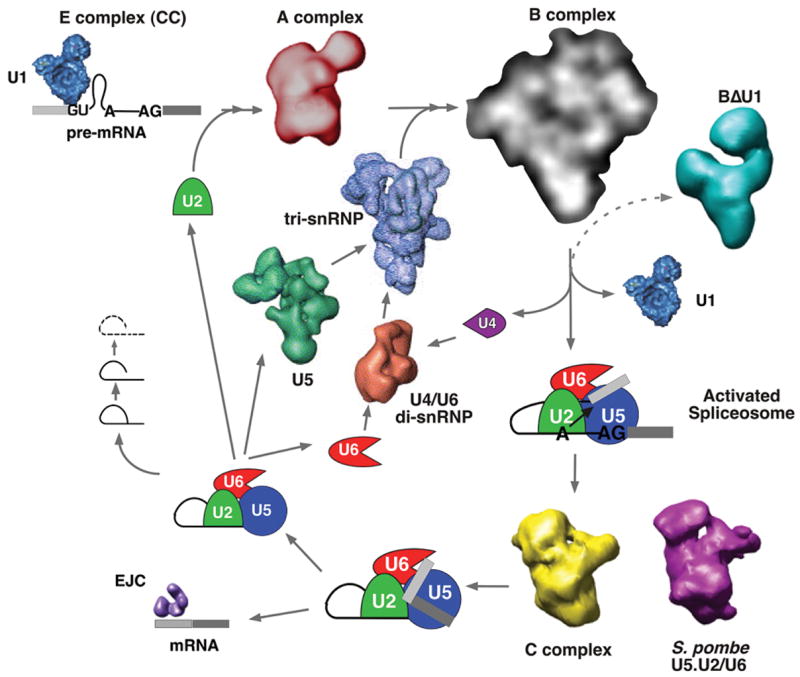

The large size of the spliceosome coupled with the challenges of isolating distinct splicing complexes have made electron microscopy and single particle reconstruction the methods of choice for visualizing the architecture of entire splicing complexes and their snRNP components (recently reviewed in [4]). These techniques are producing models for many of the splicing complex intermediates and bringing us closer to a global structural view of the splicing cycle (Figure 1). One recent addition to the gallery of spliceosome structures is the EM reconstruction of the pre-spliceosome (A complex) consisting of the U1 and U2 snRNPs assembled on pre-mRNA [5]. 2D averaged EM images of the fully assembled spliceosome (B complex) have also been published, suggesting that a 3D structure of this complex will be available in the near future [6]. Another recently published EM reconstruction represents a stable complex isolated from Schizosaccharomyces pombe that in many aspects resembles a late catalytic spliceosome [7]. The S. pombe complex contains the U2, U5, U6 snRNAs and their associated proteins, the NTC (Prp19 complex) and factors associated with the second step of splicing [7,8]. Additionally, endogenous pre-mRNA splicing intermediates were also detected is the isolated complexes [7]. The 3D structure of the complex is strikingly similar to that of a human splicing complex created by in vitro splicing reaction and arrested between the first and second steps of chemistry on a synthetic pre-mRNA (C complex) [9]. It is encouraging to see such agreement between the structures of endogenous and in vitro-generated complexes. Furthermore, the ability to genetically manipulate S. pombe holds promise for future structural analyses of splicing complexes.

Figure 1.

Toward a structural view of the spliceosome throughout the splicing cycle. Several macromolecular assemblies involved in the removal of an intron in pre-mRNA to generate mRNA have been visualized by EM and single particle reconstruction including snRNP complexes (U1, U5, U5:U4/U6 tri-snRNP, U4/U6 di-snRNP), splicing-related complexes (BΔU1, S. pombe U2.U5/U6, EJC) [43]) and structural intermediates of the spliceosome (A complex, B complex (2D averaged images only), C complex)

For all the EM structures of spliceosomes produced so far, some measure of sample heterogeneity appears to limit the resolution of the models and, as follows, the interpretation of those models. Existing electron density maps of spliceosomes lack easily identifiable features that allow individual protein or RNA elements to be pinpointed. However, advancement in interpreting EM spliceosome structures is being made by labeling of key components [10,11]. EM labeling experiments for large macromolecular assemblies like the spliceosome can be very challenging. Recurrent difficulties include generating labels that target exposed epitopes, the fragility of complexes and the low concentration of splicing complexes isolated via current protocols. The low concentration of complexes necessitates labels with very high affinities and binding strategies that take into account the time required to reach steady-state. Recently meeting these challenges, the Lührmann and Stark groups combined 2D images of antibodies and a gold-labeled oligo directed to U5 snRNA features with 3D EM models to provide a compelling initial interpretation of U5:U4/U6 tri-snRNP and spliceosome architecture [11]. Our group developed an RNA targeted label using an RNA binding domain fused to a protein that is easily recognized in EM images, a donut-shaped bacterial sliding clamp [10]. We used this label to show that the exons in spliceosomes arrested between the two steps of splicing chemistry are juxtaposed near each other in 2D averaged images [10].

Advancement of EM analysis for imaging and interpreting structures of additional splicing complexes depends on several factors. New tools for arresting the spliceosome in different conformations are necessary. Methods to deal with sample heterogeneity, either biochemically or during image processing, will allow higher resolution models to be determined. Further development of labeling strategies will lead to more in-depth interpretation of EM structures and provide important restraints for docking higher resolution structures of individual components into the EM maps (see further below).

Looking at the pieces in detail

Crystallographers and NMR spectroscopists interested in the splicing machinery have primarily found success in examining isolated domains of either spliceosome proteins or the U snRNAs. Studies of snRNAs, often by NMR analysis, have tackled domains of the U2 and U6 snRNAs at the center of the catalytic spliceosome (reviewed in [12]). Another recent example is a study of the U2 snRNA stem loop I demonstrating the role of biologically relevant RNA modifications in the stability of the structure [13].

One consideration for analyzing spliceosome components is that many of them exist in stable subassemblies. The prototypical subassemblies are the U snRNPs, each containing a unique structured snRNA, a shared core Sm/LSm heptamer, and several specific proteins. Given that the proteins in these assemblies likely depend on their neighbors for stable folding, it is often not straightforward to produce individual proteins recombinantly for structural analysis. Further adding to the challenge is the fact that many of the spliceosome proteins are very large. One such protein, Prp8p, is a 220 kD component of the U5 snRNP. This protein is very highly conserved, and several biochemical and genetic studies place it close to the sites of catalysis in the spliceosome [14]. Even though Prp8p was fabled to haunt the graveyard of impossible structural projects, a portion of this central splicing factor finally succumbed to structural analysis. The C-terminal domain of the protein from both yeast and worms was crystallized to reveal an augmented Jab1/MPN fold, a structural motif first identified in deubiquinating enzymes [15,16]. However, it appears that the fold has been co-opted in Prp8p to serve as a protein-protein interaction domain, as it is missing key active site residues and is unable to coordinate zinc. The isolated domain shows a weak affinity for ubiquitin, but the function of this interaction is not fully understood [17]. The yeast protein structure exhibits a C-terminal extension that the authors, supported by genetic data, propose may serve as a docking site for Prp8p interacting partners in U5 snRNP [15]. Interestingly, human Prp8 mutations linked to the disease retinitis pigmentosa also map to this same region, providing a potential structural framework for understanding the role of splicing in this rare cause of blindness [15,16].

Another spliceosome sub-complex, the NTC (PRP19 complex) is composed of at least eleven proteins that join the spliceosome with the U5:U4/U6 tri-snRNP during progression to the fully assembled complex [18,19]. Its namesake, Prp19, is a 57 kD complex E3 ubiquitin ligase homolog that has been shown to form tetramers with a flexible conformation as visualized by electron microscopy [20]. Structures of the U-box domain of Prp19 show how this fold is related to the RING motif of other E3 proteins and can serve as a dimerization platform for E3 oligomerization [21,22]. Notably, a role for ubiquitin in spliceosome assembly has been recently demonstrated [23], and it will be exciting to see how this observation will relate to both the Prp8 and Prp19 structures.

Several RNA binding domains (RBD) or RNA recognition motifs (RRM) found in many splicing related proteins have also been examined of late [24–29]. Although sometimes yet unpublished, a search of the PDB shows that structural genomics projects are also contributing to the catalog of splicing protein structures (Table 1), once again, often looking at isolated domains. A recently published example from the RIKEN Structural Genomics/Proteomics Initiative (RSGI) describes NMR structures of the first and second so-called SURP domains of the U2 snRNP protein SF3a120 [30]. This motif, so far found only in splicing proteins, forms a helical bundle of three alpha helices and one short 310–helix. The second SF3a120 SURP domain could only be produced in complex with a fragment of SF3a60 providing a view of at least part of the interface of between these two U2 snRNP proteins. This observation again underscores the necessity of co-expressing binding partners in macromolecular assemblies in order to study their structures.

Table 1.

Structural genomics contributions to splicing machinery structure analysis

| PDB | Protein | reference | Release year | type | SG group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2do5 | SF3b145 SAP domain | Unpublished: Suzuki, S., et al | 2007 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2dim, 2din | CDC5 Myb domain | Unpublished: Yoneyama, M., et al | 2007 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2ytc | RBM22 RBD | Unpublished: Kasahara, N et al | 2007 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2r99 | CypE ABH-like domain | Unpublished: Walker, J.R., et al | 2007 | xtal | SGC |

| 2fwk | LSM5 | [44] | 2006 | xtal | SGC |

| 2dt6 | Sf3a120 1st SURP | [29] | 2006 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2dk4 | Prp18 splicing factor motif | Unpublished: He, F., et al | 2006 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2dt7 | SF3a120 2nd SURP domain bound to SF3a60 fragment | [29] | 2006 | nmr | RSGI |

| 2ghp | Prp24 (1–3 RRMs) | Unpublished: Bae, E., et al | 2006 | xtal | CESG |

| 2fho | p14 bound to SF3b155 Fragment | [45] | 2006 | nmr | RSGI |

| 1×4a, 1×4c | ASF/SF2 RRM | Unpublished: He, F., et al | 2005 | nmr | RSGI |

| 1zkh | SF3a120 ubiquitin-like domain | Unpublished: Lukin, J.A., et al | 2005 | nmr | SGC |

| 1×5u | Sf3b49 RRM | Unpublished: Sato, A., et al | 2005 | nmr | RSGI |

| 1×4q | Prp3 PWI domain | Unpublished: He, F., et al | 2005 | nmr | RSGI |

| 1uw2 | U1-C zinc finger | [46] | 2004 | nmr | RSGI |

| 1we7 | Sf3a120 ubiquitin-like domain | Unpublished: He, F., et al | 2004 | nmr | RSGI |

Interactions between other components of the spliceosome have also been visualized in the past two years. These include the recently reviewed [31] exon junction complex (EJC) structure [32,33] and the crystal structure of U2AF65 bound to polypyrimidine tract RNA that illustrates how the RRMs of this early spliceosome assembly factor flexibly recognize a key splicing sequence in pre-mRNAs [29]. A spliceosome protein interface was examined in the X-ray structure of U2 snRNP protein p14 bound to a peptide of the SF3b155. The structure reveals how the RNA interaction surface of the p14 RRM, known to contact the bulged adenosine of the intron branch point in the assembled spliceosome, is partially occluded by SF3b155 [28,34,35]. In another crystallographic study, the interface between the U2AF-homolgy motif (UHM) of SPF45 and different fragment of SF3b155 was implicated in an alternative splicing role for SPF45 [36]. Finally, a three way protein-RNA structure of the U4/U6 di-snRNP protein Prp31’s Nop domain bound to the 15.5K protein: U4 snRNA 5′-stem loop complex shows how an RNA-protein complex can be recognized in a relaxed sequence context. The interfaces created in the complex also explain the hierarchy of assembly observed for these snRNP components [37]. Regarding high-resolution structures of yet more complex assemblies, the horizon is brightening further. Very soon Nagai and coworkers will report the structure of the functional core of human U1 snRNP (Pomeranz Krummel, Oubridge and Nagai, personal communication). And, if that was not enough, we will also soon be able to see the structure of the U4 snRNP core domain (Leung, Li and Nagai, personal communication). Exciting times are ahead indeed.

Towards the future: bringing it all together

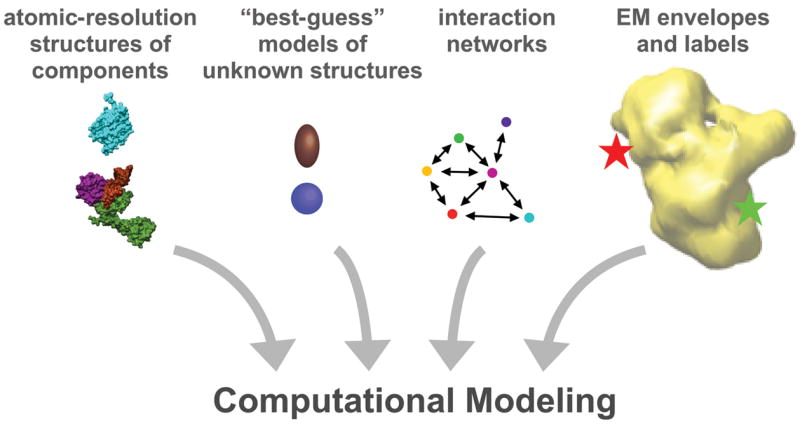

The future for structural studies of the spliceosome hold much promise, in large part because there is so much left to accomplish. The structural insights already reached have been hard fought. The challenges of dynamics, complexity and obtaining large amounts of splicing related molecules remain. One tantalizing prospect for developing an atomic model of the complex is placing the ever-increasing number of high-resolution structures of individual domains and interfaces into the spliceosome complex EM electron density maps by computational modeling (Figure 2). Methods for modeling macromolecular assemblies, such as the nuclear pore complex, are certainly becoming more robust, incorporating many types of structural and biochemical data as restraints [38,39]. The spliceosome, lacking symmetry and, as of yet, an exact parts list, is perhaps not quite a ready candidate for this exercise. However, as computational modeling techniques continue to develop and are trained on well-understood complex structures, such as the ribosome for example, the data needed for convergence to a robust model of the spliceosome will become available. Beyond additional structures and EM labels, advances in mass spectrometry techniques will allow determination of stoichiometries of spliceosome components so that we will know all the pieces of the puzzle. Interaction networks of components in spliceosome subassemblies, like the tri-snRNP and Prp19 complex, for example, are being compiled [40–42] and will be important for determining which components are located near each other. The dynamics of the splicing cycle present another important challenge to overcome, but incrementally the details will fit together in the global view to reveal the architecture of this important cellular machine.

Figure 2.

Towards combining structures of spliceosome components and complexes by computational modeling. As high-resolution structures of the over 100 components of the spliceosome and EM models of spliceosome complexes accumulate, computational modeling that incorporates interaction data and labeling information may allow for a detailed architectural model of the entire spliceosome.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Gabriel Roybal for discussion and comments. M.S.J. is supported by a U.S. National Institutes of Health grant 5R01GM72649 and a Searle Scholar Award from the Kinship Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests statement

The author declares that she has no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nilsen TW. The spliceosome: the most complex macromolecular machine in the cell? Bioessays. 2003;25:1147–1149. doi: 10.1002/bies.10394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore MJ, Query CC, Sharp PA. Splicing of precursors to mRNA by the spliceosome. In: Gesteland R, Atkins J, editors. The RNA World. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 303–357. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brow DA. Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:333–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.043002.091635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stark H, Luhrmann R. Cryo-electron microscopy of spliceosomal components. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:435–457. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behzadnia N, Golas MM, Hartmuth K, Sander B, Kastner B, Deckert J, Dube P, Will CL, Urlaub H, Stark H, et al. Composition and three-dimensional EM structure of double affinity-purified, human prespliceosomal A complexes. Embo J. 2007;26:1737–1748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deckert J, Hartmuth K, Boehringer D, Behzadnia N, Will CL, Kastner B, Stark H, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. Protein composition and electron microscopy structure of affinity-purified human spliceosomal B complexes isolated under physiological conditions. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5528–5543. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00582-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohi MD, Ren L, Wall JS, Gould KL, Walz T. Structural characterization of the fission yeast U5. U2/U6 spliceosome complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3195–3200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611591104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohi MD, Link AJ, Ren L, Jennings JL, McDonald WH, Gould KL. Proteomics analysis reveals stable multiprotein complexes in both fission and budding yeasts containing Myb-related Cdc5p/Cef1p, novel pre-mRNA splicing factors, and snRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2011–2024. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2011-2024.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jurica MS, Sousa D, Moore MJ, Grigorieff N. Three-dimensional structure of C complex spliceosomes by electron microscopy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:265–269. doi: 10.1038/nsmb728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alcid EA, Jurica MS. A protein-based EM label for RNA identifies the location of exons in spliceosomes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1378. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sander B, Golas MM, Makarov EM, Brahms H, Kastner B, Luhrmann R, Stark H. Organization of core spliceosomal components U5 snRNA loop I and U4/U6 Di-snRNP within U4/U6. U5 Tri-snRNP as revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Mol Cell. 2006;24:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butcher SE, Brow DA. Towards understanding the catalytic core structure of the spliceosome. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:447–449. doi: 10.1042/BST0330447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sashital DG, Venditti V, Angers CG, Cornilescu G, Butcher SE. Structure and thermodynamics of a conserved U2 snRNA domain from yeast and human. Rna. 2007;13:328–338. doi: 10.1261/rna.418407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grainger RJ, Beggs JD. Prp8 protein: at the heart of the spliceosome. Rna. 2005;11:533–557. doi: 10.1261/rna.2220705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pena V, Liu S, Bujnicki JM, Luhrmann R, Wahl MC. Structure of a multipartite protein-protein interaction domain in splicing factor prp8 and its link to retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Cell. 2007;25:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Shen J, Guarnieri MT, Heroux A, Yang K, Zhao R. Crystal structure of the C-terminal domain of splicing factor Prp8 carrying retinitis pigmentosa mutants. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1024–1031. doi: 10.1110/ps.072872007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellare P, Kutach AK, Rines AK, Guthrie C, Sontheimer EJ. Ubiquitin binding by a variant Jab1/MPN domain in the essential pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp8p. Rna. 2006;12:292–302. doi: 10.1261/rna.2152306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarn WY, Hsu CH, Huang KT, Chen HR, Kao HY, Lee KR, Cheng SC. Functional association of essential splicing factor(s) with PRP19 in a protein complex. Embo J. 1994;13:2421–2431. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarn WY, Lee KR, Cheng SC. Yeast precursor mRNA processing protein PRP19 associates with the spliceosome concomitant with or just after dissociation of U4 small nuclear RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10821–10825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Ren L, Hirsch JP, Chazin WJ, Walz T, Gould KL. Structural and functional analysis of essential pre-mRNA splicing factor Prp19p. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:451–460. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.451-460.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohi MD, Vander Kooi CW, Rosenberg JA, Chazin WJ, Gould KL. Structural insights into the U-box, a domain associated with multi-ubiquitination. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:250–255. doi: 10.1038/nsb906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vander Kooi CW, Ohi MD, Rosenberg JA, Oldham ML, Newcomer ME, Gould KL, Chazin WJ. The Prp19 U-box crystal structure suggests a common dimeric architecture for a class of oligomeric E3 ubiquitin ligases. Biochemistry. 2006;45:121–130. doi: 10.1021/bi051787e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellare P, Small EC, Huang X, Wohlschlegel JA, Staley JP, Sontheimer EJ. A role for ubiquitin in the spliceosome assembly pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bae E, Reiter NJ, Bingman CA, Kwan SS, Lee D, Phillips GN, Jr, Butcher SE, Brow DA. Structure and interactions of the first three RNA recognition motifs of splicing factor prp24. J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1447–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thickman KR, Sickmier EA, Kielkopf CL. Alternative conformations at the RNA-binding surface of the N-terminal U2AF(65) RNA recognition motif. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hargous Y, Hautbergue GM, Tintaru AM, Skrisovska L, Golovanov AP, Stevenin J, Lian LY, Wilson SA, Allain FH. Molecular basis of RNA recognition and TAP binding by the SR proteins SRp20 and 9G8. Embo J. 2006;25:5126–5137. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitali F, Henning A, Oberstrass FC, Hargous Y, Auweter SD, Erat M, Allain FH. Structure of the two most C-terminal RNA recognition motifs of PTB using segmental isotope labeling. Embo J. 2006;25:150–162. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schellenberg MJ, Edwards RA, Ritchie DB, Kent OA, Golas MM, Stark H, Luhrmann R, Glover JN, MacMillan AM. Crystal structure of a core spliceosomal protein interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1266–1271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508048103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sickmier EA, Frato KE, Shen H, Paranawithana SR, Green MR, Kielkopf CL. Structural basis for polypyrimidine tract recognition by the essential pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF65. Mol Cell. 2006;23:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuwasako K, He F, Inoue M, Tanaka A, Sugano S, Guntert P, Muto Y, Yokoyama S. Solution structures of the SURP domains and the subunit-assembly mechanism within the splicing factor SF3a complex in 17S U2 snRNP. Structure. 2006;14:1677–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Le Hir H, Andersen GR. Structural insights into the exon junction complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen CB, Ballut L, Johansen JS, Chamieh H, Nielsen KH, Oliveira CL, Pedersen JS, Seraphin B, Le Hir H, Andersen GR. Structure of the exon junction core complex with a trapped DEAD-box ATPase bound to RNA. Science. 2006;313:1968–1972. doi: 10.1126/science.1131981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bono F, Ebert J, Lorentzen E, Conti E. The crystal structure of the exon junction complex reveals how it maintains a stable grip on mRNA. Cell. 2006;126:713–725. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacMillan AM, Query CC, Allerson CR, Chen S, Verdine GL, Sharp PA. Dynamic association of proteins with the pre-mRNA branch region. Genes Dev. 1994;8:3008–3020. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Query CC, Strobel SA, Sharp PA. Three recognition events at the branch-site adenine. Embo J. 1996;15:1392–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corsini L, Bonnal S, Basquin J, Hothorn M, Scheffzek K, Valcarcel J, Sattler M. U2AF-homology motif interactions are required for alternative splicing regulation by SPF45. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:620–629. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Li P, Dybkov O, Nottrott S, Hartmuth K, Luhrmann R, Carlomagno T, Wahl MC. Binding of the human Prp31 Nop domain to a composite RNA-protein platform in U4 snRNP. Science. 2007;316:115–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1137924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff LM, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait BT, et al. Determining the architectures of macromolecular assemblies. Nature. 2007;450:683–694. doi: 10.1038/nature06404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alber F, Dokudovskaya S, Veenhoff LM, Zhang W, Kipper J, Devos D, Suprapto A, Karni-Schmidt O, Williams R, Chait BT, et al. The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature. 2007;450:695–701. doi: 10.1038/nature06405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen CH, Yu WC, Tsao TY, Wang LY, Chen HR, Lin JY, Tsai WY, Cheng SC. Functional and physical interactions between components of the Prp19p-associated complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1029–1037. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu S, Rauhut R, Vornlocher HP, Luhrmann R. The network of protein-protein interactions within the human U4/U6. U5 tri-snRNP. Rna. 2006;12:1418–1430. doi: 10.1261/rna.55406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohi MD, Gould KL. Characterization of interactions among the Cef1p-Prp19p-associated splicing complex. Rna. 2002;8:798–815. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202025050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stroupe ME, Tange TO, Thomas DR, Moore MJ, Grigorieff N. The three-dimensional arcitecture of the EJC core. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]