Abstract

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a highly conserved mechanism to remove helix-distorting DNA base damage. A major substrate for NER is DNA damage caused by environmental genotoxins, most notably ultraviolet radiation. Xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy are three human diseases caused by inherited defects in NER. The symptoms and severity of these diseases vary dramatically, ranging from profound developmental delay to cancer predisposition and accelerated aging. All three syndromes include neurological disease, indicating an important role for NER in protecting against spontaneous DNA damage as well. To study the pathophysiology caused by DNA damage, numerous mouse models of NER deficiency were generated by knocking-out genes required for NER or knocking-in disease-causing human mutations. This review explores the utility of these mouse models to study neurological disease caused by NER deficiency.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, demyelination, endogenous damage

Introduction

Nucleotide excision repair

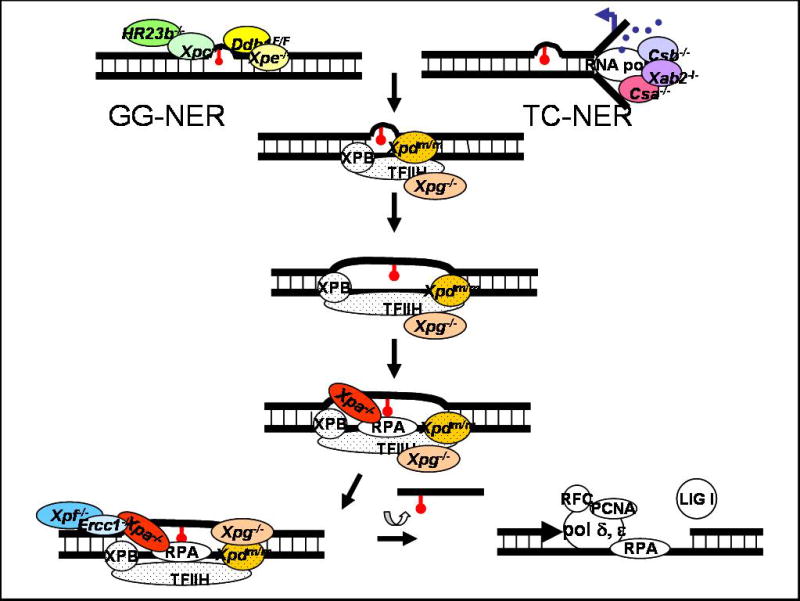

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a highly conserved multi-step pathway that removes helix-distorting DNA lesions from the genome (Figure 1). Sites of DNA damage are identified by NER in one of two ways, depending on the location of the lesion in the genome. Helix-distorting lesions anywhere in the genome are recognized by XPC in global genome NER (GG-NER). Damage recognition is facilitated HR23B or its homolog HR23A, which stabilize XPC [1, 2]. Many of the DNA lesions that are substrates for NER are caused by environmental genotoxins. For instance, UV-induced 6-4 photoproducts and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers are repaired by NER. Thus a hallmark feature of NER-deficiency is exquisite photosensitivity. A second protein complex DDB (comprised of DDB1 and DDB2/XPE) specifically facilitates recognition UV lesions by XPC-HR23B [2].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of nucleotide excision repair highlighting mutant mouse strains available.

Two subpathways of NER are delineated based on the location of a DNA lesion in the genome and how the damage is recognized. XPC-HR23B binds helix-distorting lesions throughout the genome in global genome-NER (GG-NER). This is facilitated by the DDB complex (DDB1 and XPE/DDB2) specifically in the case of damage caused by UV-irradiation. DDB is part of the Cul4A complex, which ubiquitylates XPC leading to stable association of this protein to damaged DNA. Lesions on the transcribed strand of genes can block RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription, leading to activation of transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER). Either XPC in GG-NER or CSA and CSB in TC-NER recruit the multi-subunit transcription factor TFIIH to the site of damage (subunits indicated with dots). XPG is required to stabilize TFIIH. The XPB and XPD subunits of TFIIH are helicases that unwind the DNA around the lesion. XPA and RPA then bind and stabilize the open structure and recruit ERCC1-XPF. This nuclease incises the damaged strand of DNA 5′ to the lesion. XPG makes the 3′ incision. The lesion is removed in a single-stranded oligonucleotide, leaving behind a gap that is filled by the replication machinery (polymerase δ and ε, PCNA, RPA and RFC). The DNA backbone is sealed by DNA ligase I.

Colored circles indicate gene products that have been targeted in the mouse. -/- indicates mutant strains where the protein of interest is undetectable. Homozygous deletion of Ddb1, Xab2, Xpb or Xpd is incompatible with life. Thus Ddb1 was conditionally knocked out (F/F = floxed allele) and point mutations in Xpd causing TTD or CS were knocked into the mouse genome (m/m).

Damage to bases on the transcribed strand of a gene, which block transcription, triggers transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER). CSA, CSB and XAB2 facilitate TC-NER by stabilizing RNA polymerase II near the site of damage [3]. Once the lesion is identified, GG-NER and TC-NER have a common excision mechanism. The multi-protein complex TFIIH, which is a basal transcription factor, is recruited to the site of damage through interactions with XPC-HR23B or CSB and CSA. XPG binds TFIIH and is critical for maintaining the structure of this multi-subunit complex [4]. Defects in three of the ten subunits of TFIIH (XPB, XPD and TTDA) cause photosensitivity [5], directly implicating them in NER. The XPB and XPD subunits are 3′-5′ and 5′-3′ helicases, respectively, and unwind the DNA around the lesion. Subsequently, XPA and RPA are recruited to the site and help stabilize the open structure [6]. XPA also facilitates recruitment of ERCC1-XPF nuclease, which incises the damaged strand of DNA 5′ to the lesion, at the juncture between double-strand and single-strand DNA of the open complex. XPG makes the 3′ incision. The lesion is thus excised in a 24-27 base single-stranded oligonucleotide. This leaves behind a single-strand gap that is filled by the replication machinery consisting of polymerase δ and ε, PCNA, RPA and RFC. The DNA backbone is sealed by DNA ligase I, restoring the original integrity of the DNA.

XPC, HR23B, DDB1 and DDB2 are proteins specifically required for GG-NER. CSA, CSB and XAB2 are required only for TC-NER. Defects in the two subpathways can be distinguished by measuring the cellular response to UV irradiation. Defects in GG-NER specific factors or proteins required for damage excision in NER result in reduced unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS). UDS refers to non-S phase DNA polymerization. After UV irradiation of cells, it is a direct measure of gap-filling DNA synthesis in NER. Defects in proteins required for TC-NER do not affect UDS. However, cells defective in TC-NER have impaired recovery of RNA synthesis following exposure to UV, relative to cells defective in GG-NER.

Absence of GG-NER leads to the accumulation of DNA damage and as a consequence mutations and a cancer predisposition [7]. In contrast, defects in TC-NER lead to stalled transcription which is cytotoxic, causing very different sequelae at the organism level. There are no TC-NER-specific factors, because CSB, CSA and XAB2 appear to be required for transcription itself, making it difficult to determine to what extent TC-NER protects against disease.

Diseases caused by inherited defects in nucleotide excision repair

Inherited defects in NER cause three human syndromes with striking differences in symptoms and survival. Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is characterized by photosensitivity, hyperpigmentation and ichthyosis (dry scaly skin) in sun exposed areas, a >1000-fold increased risk of basal and squamous cell carcinomas and melanomas of the skin and eyes, and a 10-fold increased risk of non-cutaneous tumors [8]. There are seven complementation groups of XP, corresponding to defects in XPA to G. The severity of symptoms is for the most part determined by the nature of the mutation and the extent to which the mutation affects NER (UDS). Thus XP-C patients, missing only GG-NER, tend to have milder disease than XP-A patients, defective in XPA protein which is required for all NER. Approximately 20% of XP patients develop progressive neurologic symptoms that can emerge as early as at birth or as late as adulthood [9]

Cockayne syndrome (CS) is caused mutations in CSA, CSB, XPB, XPD or XPG. Symptoms include postnatal growth retardation, delayed psychomotor development, cachexia, microcephaly, mental retardation, joint contractures, ataxia and abnormal gait, hypogonadism, muscle atrophy, cataracts, osteopenia, dental caries, photosensitivity and a prematurely aged appearance [10]. There are three clinical subtypes of CS: severe infantile, childhood (in which patients are normal at birth but develop rapidly progressive growth defects and premature aging symptoms), and adult (in which the same symptoms develop in childhood but progress more slowly) [11]. Patients with trichothiodystrophy have all of the classic features of CS plus cutaneous symptoms including brittle hair and nails and ichthyosis (dry, scaly skin). TTD is caused by mutations in TFIIH subunits (XPB, XPD or TTDA) leading to destabilization or dysfunction of the transcription factor [5]. The cutaneous symptoms are caused by impaired transcription of skin-specific genes [12]. In rare instances there are patients with combined XP and CS, due to mutations in XPB, XPD or XPG, and combined XP and TTD caused by mutations in XPB or XPD.

Many proteins required for NER have additional functions distinct from this repair mechanism (Table I and elaborated below). This complicates interpretation of disease phenotypes. However, to date, XPC has only been implicated in GG-NER and XPA only as a core protein in NER. Thus phenotypes caused by mutations in these genes can be interpreted to be the direct consequence of absence of GG-NER or NER.

Table I.

Comparison of neurological disease in patients with inherited defects in nucleotide excision repair and mouse models of their diseases. Shading indicates gene products that have functions distinct from NER. XP neurodegeneration includes progressive loss of fine motor control, dementia, choreoathetosis, ataxia, unsteady gait, spasticity, rigidity, hyporeflexia, loss of hearing, laryngeal dystonia and dysarthria, dysphagia and peripheral sensory axonal neuropathy [9, 13]. CS neurological disease begins post-natally and can progress rapidly (years) or slowly (decades). Symptoms includes microcephaly, mental retardation, dementia, spasticity, tremor, ataxia, gait abnormalities, hypo- or hyper-reflexia, progressive hearing loss and visual impairment [10, 11].

| Gene | Function in NER | Neurological disease in humans | Neurological disease in mice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG-NER | Xpc | Recognition of DNA damage | Adult-onset XP neurodegeneration [17]. | None reported [24, 25]. |

| Hr23a | Stabilize XPC | No patients | None reported [30]. | |

| Hr23b | Stabilize XPC | No patients | Deletion of mHR23B causes embryonic lethality (E15.5). Behavioral abnormalities occur in the fraction of mice that live [29]. | |

| Xpe/Ddb2 | Stabilize XPC after UV damage | None reported [19]. | None reported [39, 40]. | |

| Ddb1 | Stabilize XPC after UV damage | No patients | Deletion of Ddb1 causes embryonic lethality (E12.5); Deletion of Ddb1 in the brain causes apoptosis of neuronal progenitors leading to abnormal brain development [38]. | |

| TC-NER | Csa | Recruits TFIIH | CS neurological disease [11]. | None reported [54]. |

| Csb | Recruits TFIIH to promoters of damaged genes where RNA pol II is stalled | CS neurological disease [11]. | Mild defects in sensorimotor coordination and motor activity [53]. Simultaneous deletion of Xpa or Xpc leads to postnatal tremors, abnormal gait, dystonia, poor balance and progressive ataxia due to cerebellar hypoplasia [55, 57]. | |

| Xab2 | Binds CSA, CSB, RNA pol II & XPA | No patients | Deletion of Xab2 causes early embryonic lethality (E3.5) [73]. | |

| Xpd | Subunit of TFIIH; helicase | Juvenile to onset of XP neurodegeneration or CS neurological disease [76]. | A point mutation linked to TTD causes tremors, microcephaly and patchy demyelination [12, 59]. Simultaneous deletion of Xpa leads to gait abnormalities [60]. A point mutation linked with XP-CS causes transient dystonia and spasticity in juvenile male mice [61]. Simultaneous deletion of Xpa causes progressive postnatal ataxia, spasticity and gait abnormalities [61]. | |

| Xpg | 3′ nuclease in NER; binds and stabilizes TFIIH | Juvenile to adult onset XP neurodegeneration or CS neurological disease [77]. | Deletion of Xpg causes progressive ataxia due to atrophy of cerebellar Purkinje cells and apoptosis of granule cells [64]. | |

| GG- & TC-NER | Xpa | Stabilizes open intermediate; recruits ERCC1 | Juvenile to adult onset of XP neurodegeneration [9]. | None reported [41, 42]. |

| Ercc1 | Subunit of 5′ nuclease | Microcephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia and reduced foliation [48]. | Deletion of Ercc1 causes progressive dystonia, tremors and ataxia [44, 50], cerebellar hypoplasia and reduced foliation [48] | |

| Xpf | Catalytic subunit of 5′ nuclease | Juvenile to adult onset of XP neurological disease [18, 44] | Deletion of Xpf causes a phenotype similar to Ercc1-/- mice [49]. | |

Neurological disease in xeroderma pigmentosum

Neurological disease is progressive in XP and symptoms include loss of fine motor control, dementia, choreoathetosis, ataxia, unsteady gait, spasticity, rigidity, hyporeflexia, loss of hearing, laryngeal dystonia and dysarthria, dysphagia and peripheral sensory axonal neuropathy [9, 13]. Neuropathological findings include microcephaly, cerebral cortical atrophy and enlarged ventricles. The root cause is progressive neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, cerebellum, brain stem, corticospinal tract, cochlea, dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerves [9, 13, 14]. Loss of neurons appears to be due to apoptotic cell death as a consequence of unrepaired spontaneous DNA damage [15]. Although there is progressive loss of myelinated fibers in peripheral nerves, myelination itself is not affected [16]. Glial cells also appear to be unaffected [15]. Neurological disease can emerge at any age in XP from the first to fourth decade of life [14]. The age at onset of neurological disease corresponds reasonably well with the extent of the DNA repair defect [9].

The majority of XP patients with neurologic symptoms are from complementation group A (XP-A). Neurologic involvement is also seen in some XP-B and XP-D patients [16]. Milder, adult onset neurologic impairment may be seen in XP-C and XP-F patients [17, 18]. Neurologic disease has not been reported in XP-E(DDB2) patients [19].

Neurological disease in Cockayne syndrome and trichothiodystrophy

Neurologic defects in CS include postnatal growth failure of the brain leading to microcephaly, progressive dementia, mental retardation, spasticity, ataxia, progressive hearing loss and visual impairment [11, 20, 21]. Neuropathological findings in the central nervous system include atrophy of the white matter, enlarged ventricles, tigroid leukodystrophy (patchy degeneration of myelin) in the cerebral cortex, reactive gliosis, calcifications in the basal ganglia and atherosclerosis. There is also a demyelinating peripheral neuropathy, leading to neurogenic muscular atrophy. Loss of hearing is caused by degeneration of the organ of Corti, spiral and vestibular ganglia. Loss of vision is caused by atrophy of the optic nerve, retina, iris and ciliary body. Apoptotic cell death of granule cells and loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex is seen in some CS patients, similar to XP [15]. Growth retardation with microcephaly, cataracts and brain mineralization can begin in utero (severe infantile CS) or symptoms may not emerge until childhood and then progress rapidly (classic CS) or very slowly (mild CS). Neurological disease in TTD is identical to CS.

Mouse Models of NER Defects and Their Neurological Disease

GG-NER

Xpc

XPC appears to function exclusively in NER, and more specifically in GG-NER. Thus genetic deletion of Xpc in the mouse reveals the biological significance of GG-NER. Xpc-/- mice are viable, but have a reduced lifespan [22] and propensity for spontaneous tumors [23]. Xpc-/- mice do not have obvious neurological abnormalities at least in the first year of life [24, 25] (Table I). This is in contrast to XP-C patients, who may have mild, adult onset neurologic symptoms [17]. Subtle neurological deficits are difficult to detect in mice and require specialized behavioral and electrophysiological tests, thus may have been overlooked in Xpc-/- mice. Nevertheless, the fact that neurological disease is mild (or absent) in XP-C patients and Xpc-/- mice indicates that GG-NER makes a relatively small contribution to the preservation of neurological function in mammals.

Interestingly, deletion of p53 leads to neural tube defects in mouse embryos [26, 27]. Simultaneous deletion of XPC and p53 in the mouse (Xpc-/-;p53-/-) causes a significant increase in the frequency of exencephaly, relative to p53-/- mice [28]. This demonstrates that spontaneous DNA damage, normally repaired by GG-NER, can negatively impact development of the central nervous system.

hHR23A and hHR23B

HR23B forms a stable complex with XPC and facilitates GG-NER in vitro [1]. HR23A, a homolog in mammals, is redundant for this function. Deletion of HR23B in the mouse causes death in late embryonic development (>E15.5), demonstrating that HR23B has function(s) distinct from GG-NER [29]. Ten percent of mHR23B-/- mice do survive and can live up to 1 year. These mice display growth retardation, cachexia, craniofacial dysmorphology and infertility [29]. A fraction of the mice are reported to have abnormal behavior suggesting involvement of the nervous system, although analysis is incomplete [29].

In contrast, deletion of HR23A in the mouse does not impact viability or lifespan and mHR23A-/- mice appear normal to at least 18 mths of age [30]. Simultaneous deletion mHR23A and mHR23B causes early embryonic lethality (E8.5). These data demonstrate that HR23A is unable to compensate for all of the functions of HR23B. Both HR23 proteins contain a ubiquitin-like domain and two ubiquitin-associated domains [31], which are characteristic of proteins that chaperone ubiquitylated proteins to the proteosome for degradation [32]. Perturbation of protein degradation is strongly linked to numerous pathologies, in particular neurodegeneration [33, 34]. Thus it appears likely that mHR23B-/- mice will prove to have neurological disease, but not due to defective GG-NER.

DDB1 and DDB2

DDB, a complex of DDB1 and XPE/DDB2, binds UV damaged DNA with high affinity and is implicated in GG-NER specifically of UV photolesions. Each of the proteins also has functions distinct from NER and from one another. DDB1 is part of the Cullin 4A E3 ubiquitin ligase complex along with either DDB2 or CSA [35]. This complex binds damaged DNA and ubiquitylates DDB2- leading to its degradation, and XPC- leading to its stabile association with DNA and promoting GG-NER [36]. DDB1-Cul4A also targets CSB for proteosomal degradation in TC-NER, in a CSA-dependent manner, promoting RNA synthesis recovery after DNA damage [37]. Other substrates for the DDB1-Cul4A complex include histones and proteins that regulate cell cycle progression. Homozygous deletion of DDB1 in the mouse causes early embryonic lethality [38]. If DDB1 is deleted only in the CNS, mice die uniformly within 24 hrs of birth [38]. Neuropathological findings include microcephaly, enlarged ventricles, extensive hemorrhaging and loss of brain architecture. This is due to apoptosis of proliferating neuronal progenitor cells in the developing embryo. The fact that DDB1, but not NER itself, is required for brain development indicates that this profound neuropathology in the absence of DDB1 is due to the loss of a function of this protein distinct from its role in NER.

In addition to interacting with the Cul4A complex, DDB2 acts as a transcriptional activator via an interaction with E2F1 and controls p53-dependent apoptosis in response to UV irradiation [39]. Deletion of Xpe/Ddb2 in the mouse causes susceptibility to UV-induced skin carcinogenesis [39, 40]. This is similar to Xpa-/- and Xpc-/- mice and consistent with a defect in GG-NER of UV lesions. Ddb2-/- mice also have a reduced lifespan and a predisposition to spontaneous tumors [40]. A different spectrum of spontaneous solid tumors is seen in Xpc-/- mice [22]. Thus it is not clear if this tumor suppressor activity of DDB2 is attributable to a role in GG-NER of spontaneous DNA lesions or loss of another function of the protein. Neurological symptoms have not been reported in Ddb2-/- mice or in XP-E patients [19].

Core NER

Xpa

XP-A patients with mutations that severely affect NER can have profound neurological disease. In stark contrast, no neuropathology was reported in Xpa-/- mice [41, 42]. However, subtle defects may exist based on the observation that Xpa-/- mice experienced delayed neuromotor recovery and cognitive deficits following experimental brain trauma [22]. Further examination of Xpa-/- mice with newer imaging techniques and behavioral studies is warranted.

Ercc1 and Xpf

ERCC1-XPF nuclease is essential for NER [43]. However, mammalian cell lines defective in ERCC1-XPF are hypersensitive to crosslinking agents and ionizing radiation compared to cells from other XP complementation groups ([44] and Niedernhofer unpublished data). This reveals a role for ERCC1-XPF in the repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks [45, 46] and double-strand breaks [47], distinct from its function in NER. This complicates interpretation of mouse and patient phenotypes.

Deletion of Ercc1 in the mouse causes dramatically accelerated aging of multiple organ systems and death by 4 weeks of age [44]. There is only one patient reported with a mutation in Ercc1 [48]. The patient had severe growth and development delay, including microcephaly, beginning in utero, consistent with cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome. Imaging revealed hypoplasia and decreased foliation of the cerebellum. Similar defects occur in Ercc1-/- mice [49] and are accompanied by progressive dystonia, tremors and ataxia [44, 50]. Presumably, the same occurs in Xpf-/- mice [49], which appear to be a phenocopy of Ercc1-/- mice.

Mutations in hXPF are typically associated with mild XP [18]. However, if protein expression is severely reduced in humans, this can cause a progeroid syndrome with symptoms remarkably similar to Ercc1-/- mice [44]. Neurological symptoms in this progeroid Xpf patient included microcephaly, cognitive deficits, hearing loss, visual impairment, loss of fine motor control, ataxia, poor coordination, optic nerve atrophy and enlarged ventricles [44]. These symptoms are all typical of XP [9]. Thus neurological disease in this patient is likely due to defective NER, rather than the loss of another function of ERCC1-XPF. Thus it appears that Ercc1-/- and Xpf-/- mice are currently the best model of XP neurological disease. Unfortunately, there is early onset and rapid progression of symptoms in these short-lived strains, which is not the case in many XP patients. Greater promise perhaps lies in using conditional knock-out strains [51] or strains with reduced expression of ERCC1-XPF ([52] and Niedernhofer unpublished data).

TC-NER

Csa and Csb

Deletion of Csb in mice causes a phenotype significantly milder than CS [53]. Male mice display a mild growth defect (12% decrease in body weight) and both genders show very mild neurological disease, including decreased motor activity in an open field test and impaired sensorimotor coordination (decreased latency to fall from a rotarod), indicative of defects in the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Tremors, gait disturbance and ataxia are notably absent. Demyelination of neurons, characteristic of CS, is also absent in the mouse [53]. Csa-/- mice do not appear to have any neurologic abnormalities [54]. Also atypical of CS, both Csb-/- and Csa-/- mice are highly susceptible to UV-induced skin cancer [53, 54].

Deleting Xpa in Csb-/- mice (Csb-/-;Xpa-/-) causes profound growth retardation, neurologic symptoms and a severe reduction in lifespan (maximum 3 wks) [55, 56]. Neurologic symptoms include tremors, an abnormal gait, dystonia, poor balance and progressive ataxia in the first week of life [55, 56]. Neuropathological findings in the cerebellum include decreased foliation, decreased neuronal proliferation and increased apoptosis in the external granular layer, as well as decreased arborization of Purkinje cell dendrites [55]. Not surprisingly, Csb-/-;Xpc-/- mice, defective in both TC-NER and GG-NER have what appears to be a phenotype identical to Csb-/-;Xpa-/- mice [57]. Thus deletion of NER in these TC-NER mutants has a synergistic effect on disease, presumably because spontaneous DNA damage accumulates much more rapidly. What is not known is if neurological disease in these double mutant strains is more similar to XP or CS. This awaits further analysis to determine if the primary defect is neurodegeneration (XP) or demyelination (CS).

Xpd

To create a mouse model of TTD, the murine Xpd locus was targeted with a construct containing 194 basepairs from the 3′ end of human XPD cDNA with a disease-causing point mutation (R722W), and homozygous mutant mice bred [12]. XpdTTD/TTD mice mimic many aspects of TTD including brittle hair, skin abnormalities (ichthyosis, acanthosis and hyperkeratosis), cachexia, growth retardation, UV sensitivity and reduced lifespan, although the phenotype is milder than the human disease. A hallmark feature of TTD, including patients with the R722W mutation, is impaired intelligence. However, the only apparent neurological abnormality in XpdTTD/TTD mice is tremors. Myelination in the PNS appeared normal [12]. The relative weight of the brain of XpdTTD/TTD mice is maintained throughout their lifespan, indicating that the mice do not suffer from cerebral atrophy [58].

Very recently Jean-Marc Egly's group examined the neuropathology in XpdTTD/TTD more thoroughly [59]. Three week old mice showed microcephaly and demyelination in the striatum, corpus callosum and thalamus. These defects correlate with decreased transcription of genes regulated by thyroid hormone, a key mediator of neuron migration, growth of neuronal processes, myelination and synaptogenesis in brain development [59]. This study reveals a novel function of TFIIH: stabilizing thyroid hormone receptors on their responsive elements in promoters of genes expressed in the CNS. These data suggest that much of the neuropathology seen in TTD and CS may not be due to faulty DNA repair and accumulated spontaneous DNA damage, but to defective transcription.

Similar to Csb, breeding XpdTTD/TTD mice into an XPA-deficient background, to disrupt all NER, exacerbates the phenotype [60]. XpdTTD/TTD; Xpa-/- mice spontaneously develop osteoporosis leading to kyphosis and accelerated aging of the epidermis. In addition, their gait is abnormal, indicating increased neurological dysfunction [60]. This suggests that transcription is further compromised in these mice as a consequence of unrepaired DNA damage. Genes required to maintain neurological function could be directly damaged. Or stochastic damage could further compromise TFIIH levels, potentially by stabilizing the transcription factor at or near sites of damage.

To create a mouse model of XP-CS (a rare syndrome with symptoms associated with both XP and CS), a disease-causing point mutation (G602D) was knocked into the murine Xpd locus [61]. Similar to the human syndrome, XpdCS/CS mice are hypersensitive to UV and have delayed development and a propensity for skin cancer. Unlike patients, neurologic symptoms are mild and not progressive. They include dystonia and spasticity in pre-pubescent male mice only. Notably, the mice have normal sensorimotor coordination and are not ataxic. However, XpdCS/CS;Xpa-/- mice develop progressive ataxia, spasticity and gait abnormalities beginning in the first week of life. Histopathologic examination revealed degeneration of Purkinje cells but not other neurons in the cerebellum or cerebrum [61].

Xpg

XPG is the endonuclease that makes the incision 3′ of the lesion in NER [62]. It is also required to stabilize TFIIH [4]. Deletion of Xpg in the mouse leads to post-natal growth retardation and death before weaning [63]. In addition, the mice display progressive neuropathological disease including tremors, reduced spontaneous activity, ataxia and poor balance [64]. Purkinje cells in the cerebellum of Xpg-/- mice are atrophic with decreased dendritic arborization, with apoptosis of neurons in the external granular layer. These symptoms and histopathologic findings are similar to mice with cerebellar atrophy and Purkinje cell degeneration [65], suggesting that neurons in the cerebellum are particularly sensitive to spontaneous DNA damage. Granule cells release neurotrophins which are important for cerebellar development and Purkinje cell dendritogenesis [66, 67]. Therefore apoptosis of granule cells could alternatively be the primary defect leading to Purkinje cell atrophy and loss of coordinated movement.

XpgE791A/E791A and XpgD811A/D811A mice homozygous for point mutations in two amino acid residues essential for the nuclease activity of XPG develop normally [68, 69]. However, the mice and cells derived from them are hypersensitive to UV. Thus deleting the nuclease activity of XPG in the mouse mimics deletion of Xpc or Xpa, indicating that neurodegeneration in Xpg-/- mice cannot be attributed to a defect in TC-NER, which requires both XPA and XPG nuclease activity. Neurodegeneration, therefore most likely is a consequence of impaired transcription.

Truncation of XPG in exon 11 (of 15), leading to deletion of the highly conserved C-terminus, causes a phenotype similar to, but slightly milder than, deletion of the entire gene [69]. Deletion of exon 15 only, which is not conserved, has no effect on mice [69]. However, combining this mutation with deletion of Xpa leads to a phenotype like Xpg-/- mice [70]. As discussed above, Csb-/- mice have a mild phenotype. But Csb-/-;Xpa-/- mice have profound growth retardation and progressive neurodegeneration [55]. Xpg-/- and Csb-/-;Xpa-/- mice are phenotypically identical. This suggests that XPG and CSB facilitate transcription in a like manner. One plausible interpretation of these complex phenotypes is that in the absence of XPG or CSB, transcription of a damaged genome leads to a cytotoxic intermediate. The neurodegeneration in Xpg-/- and Csb-/-;Xpa-/- mice may be caused by high levels of transcription in neurons or spontaneous DNA damage in neurons.

Xab2

XAB2 (XPA-binding protein 2) interacts with XPA, CSA, CSB and RNA polymerase II. The exact function of XAB2 in TC-NER is not known. However, immunodepletion of XAB2 or siRNA knock-down causes UV hypersensitivity, impairs RNA synthesis following UV irradiation of cells, as well as inhibiting transcription [71, 72]. In the mouse, deletion of Xab2 or even just the C-terminal 162 amino acids of the protein (removing the 15th tetratricopeptide motif involved in protein:protein interactions) causes early embryonic lethality (E3.5) [73]. This cannot be attributed to defective TC-NER, but must be due to other functions of XAB2 in the cell. Recently, the human protein was co-purified as part of a large protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing [72], similar to orthologs in lower eukaryotes.

XAB2 may prove to be required for neurogenesis and brain development. Deletion of crn, a Drosophila homolog, impairs proliferation of brain neuroblasts and development of differentiated neuronal lineages in the central and peripheral nervous systems, resulting in lethality at the larval stage [74]. A rat ortholog of human XAB2 and Drosophila crn (Ath55) is highly expressed in the ventricular zone of the neocortex of developing embryos and neural stem cells, but not in differentiated neurons [75]. Further study with a conditional Xab2 knock-out will be informative.

Summary

Defects in nucleotide excision repair cause progressive neurological disease. Symptoms in CS and TTD (caused by defects in transcription and TC-NER) overlap considerably with those of XP (caused by defective GG-NER or core NER factors) including dementia, ataxia, spasticity, hearing and visual impairment, peripheral neuropathy, microcephaly and cerebral cortical atrophy. Loss of motor control is more pronounced in XP. Despite the overlap of symptoms, pathogenesis differs. In XP, the primary defect is loss of neurons, suggesting that NER is essential for maintaining neuron function and viability. In CS, demyelination is prominent, suggesting that Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes are more dependent on proteins required for TC-NER.

For the majority of mutant mouse strains generated to model NER-deficiency syndromes, there is a poor correlation between mice and patients with respect to neurological disease. ERCC1-XPF deficient mice appear to be the best model of XP neurodegeneration. Xpg-/-, Csb-/-;Xpa-/-, Csb-/-;Xpc-/-, XpdCS/CS;Xpa-/- mice have similar if not identical phenotypes and appear to be the best model of neurological disease in CS or TTD. But for both diseases, further work is required to determine if the mechanism of pathogenesis in mice is similar to humans.

In general, mouse models of NER deficiency have a milder phenotype than the human diseases they model. This in fact holds true for many genome instability disorders (e.g., Werner syndrome, Bloom's syndrome and Fanconi anemia). It is possible that mice have decreased spontaneous DNA damage relative to humans or have greater tolerance for unrepaired damage. However, this seems unlikely based on the observation that deletion of Xpa exacerbates the phenotype of all mouse models of CS and TTD dramatically. Another possible explanation is that environmental exposures strongly influence the level of spontaneous DNA damage. Experimental mice are kept under a highly controlled conditions that don't mimic of the complex environment in which humans live. Thus although neurological disease in NER-deficiency has been traditionally thought of as being driven by endogenous DNA damage, the fact that NER-deficient mice have significantly less neuropathology than humans, may mean that the damage is strongly influenced by environmental factors and therefore could be avoided to delay disease.

Acknowledgments

L.J.N. is supported by The Ellison Medical Foundation (AG-NS-0303) the NCI (CA103730, CA121411 and CA111525), the Pennsylvania Department of Health and UPCI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sugasawa K, Ng JM, Masutani C, Maekawa T, Uchida A, van der Spek PJ, Eker AP, Rademakers S, Visser C, Aboussekhra A, Wood RD, Hanaoka F, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. Two human homologs of Rad23 are functionally interchangeable in complex formation and stimulation of XPC repair activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6924–6931. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugasawa K. UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC complex, the UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex, and DNA repair. J Mol Histol. 2006;37:189–202. doi: 10.1007/s10735-006-9044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laine JP, Egly JM. When transcription and repair meet: a complex system. Trends Genet. 2006;22:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito S, Kuraoka I, Chymkowitch P, Compe E, Takedachi A, Ishigami C, Coin F, Egly JM, Tanaka K. XPG stabilizes TFIIH, allowing transactivation of nuclear receptors: implications for Cockayne syndrome in XP-G/CS patients. Mol Cell. 2007;26:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giglia-Mari G, Coin F, Ranish JA, Hoogstraten D, Theil A, Wijgers N, Jaspers NG, Raams A, Argentini M, van der Spek PJ, Botta E, Stefanini M, Egly JM, Aebersold R, Hoeijmakers JHJ, Vermeulen W. A new, tenth subunit of TFIIH is responsible for the DNA repair syndrome trichothiodystrophy group A. Nat Genet. 2004;36:714–719. doi: 10.1038/ng1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patrick SM, Turchi JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group A protein (XPA) modulates RPA-DNA interactions via enhanced complex stability and inhibition of strand separation activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16096–16101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell JR, Hoeijmakers JHJ, Niedernhofer LJ. Divide and conquer: nucleotide excision repair battles cancer and ageing. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:232–240. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraemer KKH, Lee MM, Scotto J. Xeroderma pigmentosum. Cutaneous, ocular, and neurologic abnormalities in 830 published cases. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:241–250. doi: 10.1001/archderm.123.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robbins JH, Brumback RA, Mendiones M, Barrett SF, Carl JR, Cho S, Denckla MB, Ganges MB, Gerber LH, Guthrie RA, et al. Neurological disease in xeroderma pigmentosum. Documentation of a late onset type of the juvenile onset form. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 3):1335–1361. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.3.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nance MA, Berry SA. Cockayne syndrome: review of 140 cases. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:68–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rapin I, Weidenheim K, Lindenbaum Y, Rosenbaum P, Merchant SN, Krishna S, Dickson DW. Cockayne syndrome in adults: review with clinical and pathologic study of a new case. J Child Neurol. 2006;21:991–1006. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Boer J, de Wit J, van Steeg H, Berg RJ, Morreau H, Visser P, Lehmann A, Duran M, Hoeijmakers JH, Weeda G. A mouse model for the basal transcription/DNA repair syndrome trichothiodystrophy. Mol Cell. 1998;1:981–990. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi M, Araki S, Kohyama J, Shioda K, Fukatsu R, Tamagawa K. Brainstem and basal ganglia lesions in xeroderma pigmentosum group A. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1048–1057. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.10.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins JH, Kraemer KH, Merchant SN, Brumback RA. Adult-onset xeroderma pigmentosum neurological disease--observations in an autopsy case. Clin Neuropathol. 2002;21:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohji T, Hayashi M, Shioda K, Minagawa M, Morimatsu Y, Tamagawa K, Oda M. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in human hereditary DNA repair disorders. Neurosci Lett. 1998;243:133–136. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hentati F, Ben Hamida C, Zeghal M, Kamoun M, Fezaa B, Ben Hamida M. Age-dependent axonal loss in nerve biopsy of patients with xeroderma pigmentosum. Neuromuscul Disord. 1992;2:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(06)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robbins JH, Brumback RA, Moshell AN. Clinically asymptomatic xeroderma pigmentosum neurological disease in an adult: evidence for a neurodegeneration in later life caused by defective DNA repair. Eur Neurol. 1991;33:188–190. doi: 10.1159/000116932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sijbers AM, van Voorst Vader PC, Snoek JW, Raams A, Jaspers NG, Kleijer WJ. Homozygous R788W point mutation in the XPF gene of a patient with xeroderma pigmentosum and late-onset neurologic disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:832–836. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rapic-Otrin V, Navazza V, Nardo T, Botta E, McLenigan M, Bisi DC, Levine AS, Stefanini M. True XP group E patients have a defective UV-damaged DNA binding protein complex and mutations in DDB2 which reveal the functional domains of its p48 product. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1507–1522. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapin I, Lindenbaum Y, Dickson DW, Kraemer KH, Robbins JH. Cockayne syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum. Neurology. 2000;55:1442–1449. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.10.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenbaum Y, Dickson D, Rosenbaum P, Kraemer K, Robbins I, Rapin I. Xeroderma pigmentosum/cockayne syndrome complex: first neuropathological study and review of eight other cases. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2001;5:225–242. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2001.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijnhoven SW, Hoogervorst EM, de Waard H, van der Horst GT, van Steeg H. Tissue specific mutagenic and carcinogenic responses in NER defective mouse models. Mutat Res. 2007;614:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollander MC, Philburn RT, Patterson AD, Velasco-Miguel S, Friedberg EC, Linnoila RI, Fornace AJ., Jr Deletion of XPC leads to lung tumors in mice and is associated with early events in human lung carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13200–13205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503133102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sands AT, Abuin A, Sanchez A, Conti CJ, Bradley A. High susceptibility to ultraviolet-induced carcinogenesis in mice lacking XPC. Nature. 1995;377:162–165. doi: 10.1038/377162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheo DL, Ruven HJ, Meira LB, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Tappe NJ, van Zeeland AA, Mullenders LH, Friedberg EC. Characterization of defective nucleotide excision repair in XPC mutant mice. Mutat Res. 1997;374:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong JF, Kaufman MH, Harrison DJ, Clarke AR. High-frequency developmental abnormalities in p53-deficient mice. Curr Biol. 1995;5:931–936. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sah VP, Attardi LD, Mulligan GJ, Williams BO, Bronson RT, Jacks T. A subset of p53-deficient embryos exhibit exencephaly. Nat Genet. 1995;10:175–180. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheo DL, Meira LB, Hammer RE, Burns DK, Doughty AT, Friedberg EC. Synergistic interactions between XPC and p53 mutations in double-mutant mice: neural tube abnormalities and accelerated UV radiation-induced skin cancer. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1691–1694. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70794-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng JM, Vrieling H, Sugasawa K, Ooms MP, Grootegoed JA, Vreeburg JT, Visser P, Beems RB, Gorgels TG, Hanaoka F, Hoeijmakers JH, van der Horst GT. Developmental defects and male sterility in mice lacking the ubiquitin-like DNA repair gene mHR23B. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1233–1245. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1233-1245.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng JM, Vermeulen W, van der Horst GT, Bergink S, Sugasawa K, Vrieling H, Hoeijmakers JH. A novel regulation mechanism of DNA repair by damage-induced and RAD23-dependent stabilization of xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1630–1645. doi: 10.1101/gad.260003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Spek PJ, Visser CE, Hanaoka F, Smit B, Hagemeijer A, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. Cloning, comparative mapping, and RNA expression of the mouse homologues of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae nucleotide excision repair gene RAD23. Genomics. 1996;31:20–27. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elsasser S, Finley D. Delivery of ubiquitinated substrates to protein-unfolding machines. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:742–749. doi: 10.1038/ncb0805-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergink S, Severijnen LA, Wijgers N, Sugasawa K, Yousaf H, Kros JM, van Swieten J, Oostra BA, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W, Willemsen R. The DNA repair-ubiquitin-associated HR23 proteins are constituents of neuronal inclusions in specific neurodegenerative disorders without hampering DNA repair. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefani M. Generic cell dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders: role of surfaces in early protein misfolding, aggregation, and aggregate cytotoxicity. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:519–531. doi: 10.1177/1073858407303428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groisman R, Polanowska J, Kuraoka I, Sawada J, Saijo M, Drapkin R, Kisselev AF, Tanaka K, Nakatani Y. The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2003;113:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugasawa SK, Okuda Y, Saijo M, Nishi R, Matsuda N, Chu G, Mori T, Iwai S, Tanaka K, Hanaoka F. UV-induced ubiquitylation of XPC protein mediated by UV-DDB-ubiquitin ligase complex. Cell. 2005;121:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groisman R, Kuraoka I, Chevallier O, Gaye N, Magnaldo T, Tanaka K, Kisselev AF, Harel-Bellan A, Nakatani Y. CSA-dependent degradation of CSB by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway establishes a link between complementation factors of the Cockayne syndrome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1429–1434. doi: 10.1101/gad.378206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cang Y, Zhang J, Nicholas SA, Bastien J, Li B, Zhou P, Goff SP. Deletion of DDB1 in mouse brain and lens leads to p53-dependent elimination of proliferating cells. Cell. 2006;127:929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Itoh T, Cado D, Kamide R, Linn S. DDB2 gene disruption leads to skin tumors and resistance to apoptosis after exposure to ultraviolet light but not a chemical carcinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2052–2057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306551101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon T, Chakrabortty A, Franks R, Valli T, Kiyokawa H, Raychaudhuri P. Tumor-prone phenotype of the DDB2-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2005;24:469–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vries A, van Oostrom CT, Hofhuis FM, Dortant PM, Berg RJ, de Gruijl FR, Wester PW, van Kreijl CF, Capel PJ, van Steeg H. Increased susceptibility to ultraviolet-B and carcinogens of mice lacking the DNA excision repair gene XPA. Nature. 1995;377:169–173. doi: 10.1038/377169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakane H, Takeuchi S, Yuba S, Saijo M, Nakatsu Y, Murai H, Nakatsuru Y, Ishikawa T, Hirota S, Kitamura Y. High incidence of ultraviolet-B-or chemical-carcinogen-induced skin tumours in mice lacking the xeroderma pigmentosum group A gene. Nature. 1995;377:165–168. doi: 10.1038/377165a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sijbers AM, de Laat WL, Ariza RR, Biggerstaff M, Wei YF, Moggs JG, Carter KC, Shell BK, Evans E, de Jong MC, Rademakers S, de Rooij J, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH, Wood RD. Xeroderma pigmentosum group F caused by a defect in a structure-specific DNA repair endonuclease. Cell. 1996;86:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niedernhofer LJ, Garinis GA, Raams A, Lalai AS, Robinson AR, Appeldoorn E, Odijk H, Oostendorp R, Ahmad A, van Leeuwen W, Theil AF, Vermeulen W, van der Horst GT, Meinecke P, Kleijer WJ, Vijg J, Jaspers NG, Hoeijmakers JH. A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature. 2006;444:1038–1043. doi: 10.1038/nature05456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McHugh PJ, Spanswick VJ, Hartley JA. Repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks: molecular mechanisms and clinical relevance. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:483–490. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niedernhofer LJ, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil A, de Wit J, Jaspers NG, Beverloo HB, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Minawi AZ, Saleh-Gohari N, Helleday T. The ERCC1/XPF endonuclease is required for efficient single-strand annealing and gene conversion in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007 Oct 25; doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm888. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jaspers NG, Raams A, Silengo MC, Wijgers N, Niedernhofer LJ, Robinson AR, Giglia-Mari G, Hoogstraten D, Kleijer WJ, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W. First reported patient with human ERCC1 deficiency has cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome with a mild defect in nucleotide excision repair and severe developmental failure. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:457–466. doi: 10.1086/512486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian M, Shinkura R, Shinkura N, Alt FW. Growth retardation, early death, and DNA repair defects in mice deficient for the nucleotide excision repair enzyme XPF. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:1200–1205. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.1200-1205.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McWhir J, Selfridge J, Harrison DJ, Squires S, Melton DW. Mice with DNA repair gene (ERCC-1) deficiency have elevated levels of p53, liver nuclear abnormalities and die before weaning. Nat Genet. 1993;5:217–224. doi: 10.1038/ng1193-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doig J, Anderson C, Lawrence NJ, Selfridge J, Brownstein DG, Melton DW. Mice with skin-specific DNA repair gene (Ercc1) inactivation are hypersensitive to ultraviolet irradiation-induced skin cancer and show more rapid actinic progression. Oncogene. 2006;25:6229–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weeda G, Donker I, de Wit J, Morreau H, Janssens R, Vissers CJ, Nigg A, van Steeg H, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JHJ. Disruption of mouse ERCC1 results in a novel repair syndrome with growth failure, nuclear abnormalities and senescence. Curr Biol. 1997;7:427–39. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Horst GT, van Steeg H, Berg RJ, van Gool AJ, de Wit J, Weeda G, Morreau H, Beems RB, van Kreijl CF, de Gruijl FR, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. Defective transcription-coupled repair in Cockayne syndrome B mice is associated with skin cancer predisposition. Cell. 1997;89:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Horst GT, Meira L, Gorgels TG, de Wit J, Velasco-Miguel S, Richardson JA, Kamp Y, Vreeswijk MP, Smit B, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH, Friedberg EC. UVB radiation-induced cancer predisposition in Cockayne syndrome group A (Csa) mutant mice. DNA Repair (Amst) 2002;1:143–157. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(01)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murai M, Enokido Y, Inamura N, Yoshino M, Nakatsu Y, van der Horst GT, Hoeijmakers JH, Tanaka K, Hatanaka H. Early postnatal ataxia and abnormal cerebellar development in mice lacking Xeroderma pigmentosum Group A and Cockayne syndrome Group B DNA repair genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13379–13384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231329598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van der Pluijm I, Garinis GA, Brandt RM, Gorgels TG, Wijnhoven SW, Diderich KE, de Wit J, Mitchell JR, van Oostrom C, Beems R, Niedernhofer LJ, Velasco S, Friedberg EC, Tanaka K, van Steeg H, Hoeijmakers JH, van der Horst GT. Impaired genome maintenance suppresses the growth hormone--insulin-like growth factor 1 axis in mice with Cockayne syndrome. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laposa RR, Huang EJ, Cleaver JE. Increased apoptosis, p53 up-regulation, and cerebellar neuronal degeneration in repair-deficient Cockayne syndrome mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1389–1394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610619104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wijnhoven SW, Beems RB, Roodbergen M, van den Berg J, Lohman PH, Diderich K, van der Horst GT, Vijg J, Hoeijmakers JH, van Steeg H. Accelerated aging pathology in ad libitum fed Xpd(TTD) mice is accompanied by features suggestive of caloric restriction. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:1314–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Compe E, Malerba M, Soler L, Marescaux J, Borrelli E, Egly JM. Neurological defects in trichothiodystrophy reveal a coactivator function of TFIIH. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1414–22. doi: 10.1038/nn1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Boer J, Andressoo JO, de Wit J, Huijmans J, Beems RB, van Steeg H, Weeda G, van der Horst GT, van Leeuwen W, Themmen AP, Meradji M, Hoeijmakers JH. Premature aging in mice deficient in DNA repair and transcription. Science. 2002;296:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.1070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andressoo JO, Mitchell JR, de Wit J, Hoogstraten D, Volker M, Toussaint W, Speksnijder E, Beems RB, van Steeg H, Jans J, de Zeeuw CI, Jaspers NG, Raams A, Lehmann AR, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JH, van der Horst GT. An Xpd mouse model for the combined xeroderma pigmentosum/Cockayne syndrome exhibiting both cancer predisposition and segmental progeria. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Donovan A, Davies AA, Moggs JG, West SC, Wood RD. XPG endonuclease makes the 3′ incision in human DNA nucleotide excision repair. Nature. 1994;371:432–435. doi: 10.1038/371432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harada YN, Shiomi N, Koike M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Hirota S, Kitamura Y, Kitagawa M, Matsunaga T, Nikaido O, Shiomi T. Postnatal growth failure, short life span, and early onset of cellular senescence and subsequent immortalization in mice lacking the xeroderma pigmentosum group G gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2366–2372. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun XZ, Harada YN, Takahashi S, Shiomi N, Shiomi T. Purkinje cell degeneration in mice lacking the xeroderma pigmentosum group G gene. J Neurosci Res. 2001;64:348–354. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lalonde R, Strazielle C. Spontaneous and induced mouse mutations with cerebellar dysfunctions: behavior and neurochemistry. Brain Res. 2007;1140:51–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindholm D, Hamner S, Zirrgiebel U. Neurotrophins and cerebellar development. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1997;5:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sadakata T, Kakegawa W, Mizoguchi A, Washida M, Katoh-Semba R, Shutoh F, Okamoto T, Nakashima H, Kimura K, Tanaka M, Sekine Y, Itohara S, Yuzaki M, Nagao S, Furuichi T. Impaired cerebellar development and function in mice lacking CAPS2, a protein involved in neurotrophin release. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2472–2482. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2279-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tian M, Jones DA, Smith M, Shinkura R, Alt FW. Deficiency in the nuclease activity of xeroderma pigmentosum G in mice leads to hypersensitivity to UV irradiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:2237–2242. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2237-2242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shiomi N, Kito S, Oyama M, Matsunaga T, Harada YN, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Shiomi T. Identification of the XPG region that causes the onset of Cockayne syndrome by using Xpg mutant mice generated by the cDNA-mediated knock-in method. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3712–3719. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3712-3719.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shiomi N, Mori M, Kito S, Harada YN, Tanaka K, Shiomi T. Severe growth retardation and short life span of double-mutant mice lacking Xpa and exon 15 of Xpg. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nakatsu Y, Asahina H, Citterio E, Rademakers S, Vermeulen W, Kamiuchi S, Yeo JP, Khaw MC, Saijo M, Kodo N, Matsuda T, Hoeijmakers JH, Tanaka K. XAB2, a novel tetratricopeptide repeat protein involved in transcription-coupled DNA repair and transcription. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34931–34937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kuraoka I, Ito S, Wada T, Hayashida M, Lee L, Saijo M, Nakatsu Y, Matsumoto M, Matsunaga T, Handa H, Qin J, Nakatani Y, Tanaka K. Isolation of XAB2 complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing, transcription and transcription-coupled repair. J Biol Chem. 2007 NOv 2; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706647200. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yonemasu R, Minami M, Nakatsu Y, Takeuchi M, Kuraoka I, Matsuda Y, Higashi Y, Kondoh H, Tanaka K. Disruption of mouse XAB2 gene involved in pre-mRNA splicing, transcription and transcription-coupled DNA repair results in preimplantation lethality. DNA Repair (Amst) 2005;4:479–491. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang K, Smouse D, Perrimon N. The crooked neck gene of Drosophila contains a motif found in a family of yeast cell cycle genes. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1080–1091. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amada N, Tezuka T, Mayeda A, Araki K, Takei N, Todokoro K, Nawa H. A novel rat orthologue and homologue for the Drosophila crooked neck gene in neural stem cells and their immediate descendants. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2003;133:615–623. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lehmann AR. The xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) gene: one gene, two functions, three diseases. Genes Dev. 2001;15:15–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.859501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nouspikel T, Lalle P, Leadon SA, Cooper PK, Clarkson SG. A common mutational pattern in Cockayne syndrome patients from xeroderma pigmentosum group G: implications for a second XPG function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3116–3121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]