Abstract

Context:

Professional socialization during formal educational preparation can help students learn professional roles and can lead to improved organizational socialization as students emerge as members of the occupation's culture. Professional socialization research in athletic training is limited.

Objective:

To present the role of legitimation and how it influences the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students.

Design:

Modified constructivist grounded theory and case study methods were used for this qualitative study.

Setting:

An accredited undergraduate athletic training education program.

Patients or Other Participants:

Twelve second-year students were selected purposively. The primary sample group (n = 4) was selected according to theoretical sampling guidelines. The remaining students made up the cohort sample (n = 8). Theoretically relevant data were gathered from 14 clinical instructors to clarify emergent student data.

Data Collection and Analysis:

Data collection included document examination, observations, and interviews during 1 academic semester. Data were collected and analyzed through constant comparative analysis. Data triangulation, member checking, and peer-review strategies were used to ensure trustworthiness.

Results:

Legitimation from various socializing agents initiated professional socialization. Students viewed trust and team membership as rewards for role fulfillment.

Conclusions:

My findings are consistent with the socialization literature that shows how learning a social or professional role, using rewards to facilitate role performance, and building trusting relationships with socializing agents are important aspects of legitimation and, ultimately, professional socialization.

Keywords: clinical education, preservice professional preparation, socializing agents, role performance, grounded theory

Key Points.

Athletic training education should incorporate effective socialization strategies to improve the quality of clinical educational experiences for athletic training students and promote their legitimation as developing athletic trainers.

Successful role performance is an important determinant of legitimation and professional socialization of preservice athletic trainers. Efforts should be made programmatically to orient students to program goals and expectations and to decrease potential role conflict, which could be a negative effect of insufficient socialization.

Developing relationships facilitates legitimation in preservice athletic trainers. Thus, individuals such as patients, coaches, clinical instructors, and peer mentors serve as socializing agents to preservice athletic trainers and should be considered when developing socialization strategies for preservice and inservice professionals.

Professional socialization is the process by which an individual learns the roles and responsibilities of his or her profession and emerges as a member of the professional culture.1–3 The professional socialization process often is defined by 3 phases: (1) recruitment, (2) professional preparation, and (3) organizational socialization.1,2 The first 2 phases typically are considered preservice or anticipatory socialization phases that occur before and during the professional education period. Organizational socialization is considered the in-service period during which the individual interprets and assumes the role of a qualified professional within a given work environment.1,2,4–6 Although these phases are distinct, they overlap and may occur concurrently.1 The professional socialization process as it relates to teacher education and the preparation of various medical and allied health professionals is well documented. In athletic training, limited research has focused on anticipatory (recruitment)7 and organizational socialization.4–6,8

Although research relative to professional socialization during students' professional preparation years is limited in athletic training,9–11 investigators have suggested that various determinants positively or negatively affect the professional socialization and developing identity of preservice students in other fields.1–3,12–27 Relative to athletic training, Pitney5 and Pitney et al6 described a need to study the effect of student socialization during the undergraduate athletic training education experience. Stevens et al8 determined the perceived role of clinical and field experiences during the professional preparation period in the professional socialization of entry-level athletic trainers (ATs). In addition, 1 component of the National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) 2007 strategic plan28 was to gain a better understanding of the influence of the professional preparation process on the socialization of entry-level ATs into the work environment. Such discourse suggests that deliberate and planned control of the socialization of preservice athletic training students during the professional preparation years could enhance their overall professional education experience and potentially lead to improved organizational socialization when they become credentialed members of the athletic training community. Thus, individuals involved in educating athletic training students must understand the many factors, including professional socialization, that influence professional preparation and growth of students. The ultimate purpose of my research was to develop a preliminary theoretical model of how students develop professionally through the process of professional socialization in an established, accredited athletic training education program (ATEP). A comprehensive review of the entire model and related research findings11 is beyond the scope of this paper. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to present the role of legitimation and how it influences the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students.

Methods

Theoretical Framework

I used modified constructivist grounded theory and case study methods as the primary modes of inquiry for this study, because my intent was to discover a preliminary theoretical model of professional socialization based on 1 case (ATEP program). The underlying assumption of grounded theory is that theory is generated as an ongoing developmental process that emerges from the data.29 Grounded theory also is based upon the perspective of symbolic interactionism,30,31 in which meaning is constructed through social interaction.31,32 Because the process of learning a professional role through reciprocal social interaction is the means through which socialization occurs,33 symbolic interactionism is relevant to my research.

Setting

The setting for this study was an established, Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP)–accredited (now Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education–accredited) undergraduate ATEP at a large National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A institution in the Midwest. Before participant recruitment, the institutional review board approved the purpose and methods of the research. The program was a convenience sample based on ease of access; however, the well-established history of the program was relevant to the overall objectives of the research. The program involved with the investigation was one in which I had an opportunity to develop a relationship with administrators and instructors. Thus, program access was more readily available after the methods were explained and confidentiality was guaranteed.

Participants

I purposively recruited second-year athletic training students (juniors) because they were considered the mainstream cohort; they were neither just beginning nor culminating their professional education experience. Second-year students participated daily in clinical education and rotated among 3 clinical assignments during each academic semester. Students also were enrolled in therapeutic agents and emergency management courses at the time of data collection. As sophomores, the athletic training students had completed clinical observations approximately 2 to 3 times per week with a variety of clinical assignments throughout the year and had completed athletic training coursework in strapping and bandaging, injury assessment, and general medical issues.

Twelve second-year athletic training students participated from a recruitment class of 18. I used the theoretical sampling guidelines of grounded theory to select the primary sample group (PSG) (3 women, 1 man; age = 20.75 ± 1.5 years). The remaining second-year students who participated made up the cohort sample group (CS) (5 women, 3 men; age = 22.86 ± 4.22 years). Fourteen clinical instructors participated (7 women, 7 men; 10 ATs, 1 physician, 3 Board of Certification–certified graduate students). Three of the 10 ATs were program administrators. Only theoretically relevant data were gathered from the clinical instructors to clarify emergent data from students. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Data Collection Procedures

I examined documents, observed students during clinical experiences, and interviewed select students and clinical instructors during 1 academic semester. I reviewed theoretically relevant national and local curricular materials, such as CAAHEP accreditation standards and guidelines, NATA educational competencies, and program self-study documents. The PSG and CS participants were asked to submit student self-assessments (n = 19) and student clinical experience evaluations (n = 14) at the conclusion of each of 2 clinical rotations and to submit student reflective journals monthly throughout the practicum class (n = 16). Document review also included the examination of practicum evaluations that the clinical instructors completed for each participant at the conclusion of 2 clinical rotations (n = 19).

Acting as a participant-observer, I observed each student in the PSG twice during each of the first 2 clinical-experience rotations of the semester. Field notes were maintained. The PSG students also participated in formal, semistructured interviews at the beginning of the semester and after each of the 2 observations. Clinical instructors to whom each PSG participant was assigned for both clinical rotation periods also were interviewed on 1 occasion (n = 8). These clinical instructor interviews were scheduled after observations were complete for each PSG participant for the given rotation. I conducted 1 follow-up clinical instructor interview to clarify data. In addition, I selected the 3 program administrators to interview based on their knowledge and perceptions of the curriculum from their different administrative roles. I conducted a follow-up interview with 1 of these administrators to assist in the clarification of emerging data. I also conducted focus-group interviews with the CS and PSG at the beginning and end of the semester. Program administrators and clinical instructors were not present during these focus-group interviews.

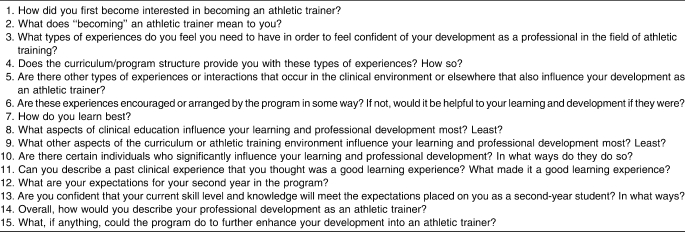

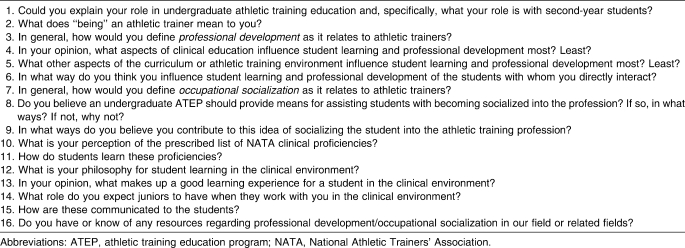

A different outline of questions was used for each group (PSG, clinical instructor, focus group, administrators). Tables 1 and 2 present examples of preliminary interview questions for the individual PSG and clinical instructor interviews, respectively. Formal interviews lasted approximately 30 to 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Names were changed to ensure confidentiality.

Table 1.

Primary Sample Group Interview 1: Preliminary Outline of Questions

Table 2.

Clinical Instructor Interview 1: Preliminary Outline of Questions

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

I used data triangulation, member checking, and peer-review strategies to ensure trustworthiness. I also maintained a personal journal to record my thoughts, questions, and potential biases that were specific to the research.

Data analysis procedures were based upon Glaser and Strauss'29 4-stage approach to constant comparative analysis that includes continually reducing and recoding relevant and representative data according to theoretically defined themes or categories. I initially identified general theoretical variables based on previous experience and research in the field, literature from related fields, discussions with informants, and early identification of common variables that became apparent through initial data collection. I coded early relevant data according to these conceptual categories, as well as by the properties of these categories as they became apparent. I wrote brief memoranda in my field notes, as well as on journal and interview transcriptions. Coded data from student journals also were organized categorically. Initial interpretations were more thoroughly analyzed and revised through monthly focused coding to represent ongoing emergent categories or themes. In the final stages of analysis, I developed a preliminary theoretical model to describe the professional socialization of preservice ATs in 1 ATEP.11

Results

Legitimation

Results revealed that legitimation initiates the process of professional socialization in second-year athletic training students because it stimulates meaningful experiential learning and, thus, formation of professional identity, which are other components of the proposed theoretical model of preservice professional socialization.11 Legitimation occurs as students look to others for acceptance to affirm their developing professional identity.23 Three common themes emerged that depict legitimation as an important element in the socialization of athletic training students in this setting. Herein, I describe the role of socializing agents; the effect of role performance; and the ways that perceived rewards for role performance facilitated legitimation and, ultimately, professional socialization of second-year athletic training students.

The Role of Socializing Agents on Legitimation

Results revealed that the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students was initiated by legitimation from various socializing agents. Second-year athletic training students looked for affirmation from others who accepted them in their professional roles. Athletes (patients), clinical instructors, graduate students, coaches, and peer mentors served as legitimators, and thus socializing agents, as they helped students gain confidence in their identities as preservice ATs. A PSG participant provided a representative example of how an athlete accepted her in the role of health care provider:

…it was probably 2 weeks ago. It was just before the end of practice and Hannah [a graduate student] and I were both there .… One of the guys had tripped and hurt his ankle .… The guys came running to me to go help him. It kind of justified my being there. They did not immediately run to Hannah, and she was not doing anything important. They could have gone to her but they came to me and asked me to take a look at him. I got him to the [athletic] training room and evaluated him, and, when Hannah came in, she basically said it was a good job and I was right. (Molly, PSG interview 3)

In the example, the athlete recognized Molly's role as a capable athletic training student. The graduate student, who was an AT, also acknowledged Molly's correct injury assessment of the athlete, thus legitimating Molly's identity as a developing AT. Data also suggested that some athletic training students were active participants in making their learning experiences meaningful. In such cases, students could be considered agents in affirming their own professional identities. The literature supports this finding, suggesting that students use the process of self-legitimation or self-evaluation to further develop their perspectives as preservice professionals.25

The Effect of Role Performance on Legitimation

Data indicated that, for second-year students to demonstrate competence as ATs, they must feel as if they had a particular role to play within the team community. This occurred through implicit or explicit role expectations from clinical instructors, as well as student acceptance of expected responsibilities.

Another PSG participant explained how the assignment and acceptance of responsibility legitimated the students' roles within the ATEP culture:

In the past few weeks, we have been told to do certain things and have been expected to understand what the staff [athletic] trainer was talking about and go do it. Take responsibility for certain actions .… If the staff athletic trainer does not feel confident with you doing that, he wouldn't tell you to do certain things, so in return it makes you feel confident. (Tammy, PSG interview 1)

In this case, clinical instructors helped to promote student legitimation through the designation of roles and responsibilities within the team community. Data also suggested that such role expectations were embedded in a progressive sequence of responsibilities that depended upon students' abilities to meet professional expectations. A clinical instructor explained that expectations of second-year students “are a moveable standard based on the confidence level of the student” (James, clinical instructor interview 1).

Students concurred with clinical instructors that role expectations depended upon the student's level in the program. As did others, Molly described the sophomore (or first) year as “an observation year” in which students are expected to try to “see as many things as you possibly can” and yet “will not be expected to necessarily take care of someone.” During her first interview at the beginning of her second year in the ATEP, Molly was “not really sure” what her role was to be that year. Although other students also were somewhat unsure of their roles during the second year, some described it as a “hands-on year” to “find out what it's all about” (focus group interview 2). Students concurred that in their third (or senior) year, they were expected to be “decision makers,” but they knew that the extent of such responsibilities would depend upon each senior's clinical assignment.

Observations indicated that second-year students fulfilled a wide variety of roles, primarily depending upon the clinical environment to which they were assigned and also depending on students' initiative to get involved. Tammy explained, “When you are a sophomore, everyone knows that you don't know very much. I feel like I have a year to learn how to be a first responder. I feel that now [as a junior] I have enough knowledge and information that, if I didn't respond in that way, it would be looked down upon. One of my responsibilities is to be a first responder” (PSG interview 2).

This student's comment demonstrates how students' roles as health care providers within the team community are assumed in a progressive sequence and that these roles often are implicit rather than explicit. Tammy perceived that, as a sophomore, she was still learning first-aid skills and that it was acceptable for her to remain a bystander as a first-year student in the program. As a second-year student, however, she perceived that clinical instructors and other members of the community would expect her to perform her role as a first responder by administering first-aid care, if needed. Thus, students perceived that appropriate role performance was expected by various socializing agents in the community, such as clinical instructors, coaches, and athletes.

The Influence of Perceived Rewards on Legitimation

Data indicated that participants perceived that building trusting relationships with socializing agents facilitated legitimation. In addition to affirming their roles, second-year athletic training students concurred that building relationships of trust with the athletes and other socializing agents was rewarding and important to their professional development. When discussing his professional development, Damon stated, “They have to trust you. You are thrown into it, and you have to earn their trust. That is very important” (PSG interview 1). Students saw trust as a reward given when they appropriately fulfilled their roles, and it also heightened the “sense of belonging in the [athletic] training room” (Damon, PSG reflective journal) and as a member of the team community. Even a simple “thank you” from an athlete was a seen as a rewarding affirmation of their professional roles: “Thank you from an athlete will do wonders for you.… Something like that makes you feel good about your athletes' trusting you” (Laura, PSG interview 2).

Like other students, Molly believed that trust stemmed from building relationships with athletes on a personal and professional level: “I had to develop a trust with them more on a personal level before I would be able to do some things… they are not going to come to you if they do not feel comfortable with you as a person and not just someone who is trying to tell them what to do” (PSG interview 2).

Students also believed that the assignment of greater responsibilities by the clinical instructor indicated that the clinical instructor trusted them. In turn, if students felt trusted, then they felt confident to take on more responsibility and thereby progressively to fulfill more demanding roles as preservice ATs. Developing relationships of trust also enabled students to feel as though they were part of the team. Students perceived that such team acceptance provided them with more frequent opportunities to demonstrate role performance. A representative example from 1 student demonstrated the idea that students felt legitimated as they had the opportunity to build relationships and demonstrate successful role performance during their second year:

Being there … during preseason gave me the opportunity to get to know everyone and really get involved, unlike last year. I think the majority of my class felt the same way with their respective sports. They all seemed to really enjoy their first chance to really get their hands on some of the athletes and have something really expected of them .… [It's] great to have a sense of belonging in the TR [athletic training room] for once. It was nice to have the athletes come up to and ask for something with confidence that you will perform it correctly and indeed do it. (Damon, reflective journal)

As students were able to meet expectations and successfully fulfill their roles, members of the sports medicine and athletic team community rewarded them with more trust, thereby facilitating team membership and, thus, legitimating their roles within the community.

Discussion

The literature suggests that preprofessional students look to gain a sense of affirmation, or legitimation, from socializing agents.* Athletes, clinical instructors, graduate students, coaches, and peer mentors serve as socializing agents as they accept second-year athletic training students in their developing professional roles. My data relative to legitimation were consistent with the professional socialization literature. Pitkala and Mantyranta35 found that support and trust from patients increased medical students' self-images as future physicians. Eli and Shuval36 reported that patients, as well as senior peers, served as socializing agents for dental students by accepting or rejecting the student's role as a professional. As I found for athletic training students, Olesen and Whittaker23 discovered that legitimators for nursing students included, but were not limited to, family and friends and program faculty, peers, patients, and physicians.

Clinical instructors and other socializing agents facilitate legitimation by designating roles and expectations to the athletic training students. Second-year athletic training students gained acceptance from members of the community by taking on responsibility and fulfilling explicit and implicit professional roles. Thus, my data indicated successful role performance is an important determinant in the professional socialization of preservice ATs because it ultimately leads to legitimation. These findings were consistent with the findings in the socialization literature about the importance of learning social or professional roles.3,13,16,19,23,33,35,37 This included understanding the rules and norms of the social structure and then demonstrating competence in fulfilling explicit and implicit behavioral expectations of the particular society or culture.33 Both accepting responsibility that is given and exercising responsibility have been demonstrated as important aspects of role performance and, thus, legitimation23 and the professional socialization of preprofessional students.13

The use of rewards and punishments to facilitate role performance33,37 and ultimately allow students to internalize successfully performed professional behaviors37 has been explained in the literature. Socializing agents rewarded preservice athletic training students for appropriate role performance with trust. As I found with athletic training students, Dunn et al16 also found that a simple “thank you” gave nursing students the satisfaction that they had met the needs of and made a difference to their patients.

My results indicated that second-year athletic training students took on a wide variety of roles and responsibilities in the clinical setting. The nature of the clinical environment, as well as the student's initiative to get involved, influenced his or her ability to adjust to these roles. Becker et al13 asserted that people participate in “situational adjustment” by taking on role characteristics that a particular setting requires. Somewhat similar to Becker and associates'13 idea of situational adjustment, I found that the students had both implicit and explicit understandings that role expectations changed as they progressed through the program. Some athletic training students were unsure, however, of their roles as members of athletic training teams at the beginning of their second year in the ATEP. Thus, it can be concluded that at least during the first semester of the second year, students were unsure of their roles. Dobbs37 specifically linked poor socialization with an inadequate understanding of role expectations. His findings are comparable with the finding that high school basketball coaches and ATs did not demonstrate the same understanding of role expectations of ATs in this work setting.4 Mensch et al4 further suggested that such role conflict could lead to job dissatisfaction. Role conflict with athletic training students could be considered a negative effect of insufficient socialization. Because role performance is an important determinant of legitimation and ultimately professional socialization of preservice ATs, efforts should be made programmatically to resolve such potential role conflict.

The findings of my study are consistent with the literature that states that “feeling part of the team” is an important aspect of role integration and, thus, professional socialization,12,16,19 ultimately allowing preprofessional students to accept more responsibility,19 contribute to team outcomes,16 build important relationships with mentors,12,16 and develop “heightened feelings of self-worth when they were treated and respected as colleagues.”16(p396)

In athletic training research, Pitney et al6 discussed the importance of relationships in the later stages of organizational socialization of inservice ATs as a means to further understand their roles as professionals. In comparison, my findings indicated that developing relationships is important to preservice ATs in the professional preparation stage of professional socialization because relationships facilitate legitimation. Regardless, they seem to be a key determinant in the professional socialization of ATs at various stages of their professional development and, thus, should be considered when developing socialization strategies for preservice and inservice professionals.

Limitations

My study did have limitations. Data collection was limited to 1 academic semester. I believe that I achieved theoretical saturation relative to my primary research questions because the research data primarily confirmed and further developed research data from my pilot study. I acknowledge, however, that factors such as student learning styles, background, goals, and expectations surfaced throughout this research but were beyond the scope of my study. In addition, many political and sociocultural determinants also may influence the professional socialization of preservice ATs. Thus, focusing on such issues in future research may be valuable.

The study of cohorts at all levels may have provided unique insight into the professional socialization of preservice ATs. However, I chose to limit my sample to the group that seemed most representative of my theoretical purposes (second-year students). As previously mentioned, I had an established professional relationship with program administrators and a few clinical instructors. I believed that this relationship improved my ability to use this site for data collection purposes and may have increased the amount of data that I received informally from clinical instructors and/or administrators. I had no previous relationship with any students in the program other than previous interaction during collection of pilot study data. At times, students asked me questions that were professional in nature, thus facilitating my role as a participant-observer. I kept a record in my personal journal of such interactions and reflected on any potential biases. Although personal biases to some extent are an accepted element of qualitative research, I attempted to control for such influences to ensure trustworthiness, as described.

Conclusions

Understanding the process of professional socialization during the professional preparation years may improve the professional development of athletic training students and enhance their socialization as ATs when they enter the work environment. Research suggests that clinical education and field experiences are components of the professional education process that are important to the socialization of preprofessional students in various fields* and to the organizational socialization of entry-level ATs.8 However, research also indicates that such field experiences are not automatically valuable to students.25,38,39 Athletic training educators are encouraged to identify socializing factors within their clinical settings to ensure that such factors facilitate the professional growth and socialization of their students. In addition, these educators may want to consider incorporating the following socialization strategies to promote student feelings of legitimation and, ultimately, professional socialization:

1. Develop strategies to educate and orient students and all staff, including graduate students, to program goals and expectations.

2. Orient students to new roles and expectations within various clinical environments as soon as possible to decrease potential role conflict. Encourage clinical instructors to meet regularly with students to promote communication and provide students with regular opportunities to discuss ideas, questions, conflicts, or changing expectations.

3. Provide regular, planned opportunities for progressing student responsibilities and roles in the clinical environment and provide regular feedback to affirm students' successful fulfillment of such roles and responsibilities.

4. Provide various avenues for formal and informal interaction with members of the athletic training community to further establish trusting relationships and, thus, facilitate legitimation. Consider joint programs and socializing efforts with athletics to build relationships with coaches and athletes.

5. Provide regular, ongoing opportunities to educate clinical instructors (including graduate students involved in undergraduate education) about the importance of their roles in facilitating the professional socialization of athletic training students. Develop purposeful ways to use such individuals as socializing agents in the clinical setting and offer strategies and professional development opportunities to assist clinical instructors in developing their skills as socializing agents and mentors.

In conclusion, effective socialization strategies can improve the quality of clinical educational experiences for athletic training students, can facilitate their feelings of legitimation as developing ATs, and ultimately can facilitate their socialization into the profession.

Acknowledgments

I thank the program and participants of my study, especially the students who participated as members of the primary sample group. I also thank Dr Ellen Brantlinger, Dr Jesse Goodman, Dr Tom Schwen, and Dr John Schrader for their assistance during my research. This project was funded in part by a grant from the Pi Lambda Theta Educational Endowment, Bloomington, Indiana.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Stroot S.A, Williamson K.M. Issues and themes of socialization into physical education. J Teach Phys Educ. 1993;12(4):337–343. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Templin T.J, Schempp P.G. An introduction to socialization into physical education. In: Templin T.J, Schempp P.G, editors. Socialization Into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Vol. 1989. Indianapolis, IN: Benchmark Press; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thielens W. The Socialization of Law Students: A Case Study in Three Parts. New York, NY: Arno Press; p. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mensch J, Crews C, Mitchell M. Competing perspectives during organizational socialization on the role of certified athletic trainers in high school settings. J Athl Train. 2005;40(4):333–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitney W.A. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitney W.A, Ilsley P, Rintala J. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mensch J, Mitchell M. Attractors and barriers to a career in athletic training: exploring the perceptions of potential recruits [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):21S. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens S.W, Perrin D.H, Schmitz R.J, Henning J.M. Clinical experience's role in professional socialization as perceived by entry-level athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):22S. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klossner J.C. The role of legitimation in the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students in a CAAHEP-accredited program [abstract] J Athl Train. 2006;41(suppl 2):21S. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klossner J.C. The process of meaningful experiential learning in the professional socialization of second-year athletic training students. Poster presented at: Southeast Athletic Trainers' Association Athletic Training Educators' Conference; February 10, 2006; Atlanta, GA.

- 11.Klossner J.T. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information and Learning Co; “Becoming” an athletic trainer: the professional socialization of pre-service athletic trainers; p. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atack L, Comacu M, Kenny R, LaBelle N, Miller D. Student and staff relationships in a clinical practice model: impact on learning. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(9):387–392. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001201-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker H.S, Greer B, Hughes E.D, Strauss A.L. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; p. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell I.E, Larrivee L, Field P.A, Day R.A, Reutter L. Learning to nurse in the clinical setting. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20(6):1125–1131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20061125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodds P. Trainees, field experiences, and socialization into teaching. In: Templin T.J, Schempp P.G, editors. Socialization Into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Indianapolis, IN: Benchmark Press; 1989. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn S.V, Ehrich L, Mylonas A, Hansford B.C. Students' perceptions of field experience in professional development: a comparative study. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(9):393–400. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20001201-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick J.M, While A.E, Roberts J.D. Key influences on the professional socialisation and practice of students undertaking different pre-registration nurse education programmes in the United Kingdom. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33(5):506–518. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(96)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graber K.C. Teaching tomorrow's teachers: professional preparation as an agent of socialization. In: Templin T.J, Schempp P.G, editors. Socialization Into Physical Education: Learning to Teach. Indianapolis, IN: Benchmark Press; 1989. pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray M, Smith L.N. The professional socialization of diploma of higher education in nursing students (Project 2000): a longitudinal qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(3):639–647. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayden J. Professional socialization and health education preparation. J Health Educ. 1995;26(5):271–274. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lurie E.E. Nurse practitioners: issues in professional socialization. J Health Soc Behav. 1981;22(1):31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nesler M.S, Hanner M.B, Melburg V, McGowan S. Professional socialization of baccalaureate nursing students: can students in distance nursing programs become socialized. J Nurs Educ. 2001;40(7):293–302. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20011001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olesen V.L, Whittaker E.W. The Silent Dialogue: A Study in the Social Psychology of Professional Socialization. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; p. 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson B, Lindquist L.I, Engardt M, Aitman C. Professional socialization: students' expectations of being a physiotherapist. Med Teach. 2002;24(6):622–627. doi: 10.1080/0142159021000063943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross E.W. Becoming a teacher: the development of preservice teacher perspectives. Action Teach Educ. 1988;10(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabari J.S. Professional socialization: implication for occupational therapy education. Am J Occup Ther. 1985;39(2):96–102. doi: 10.5014/ajot.39.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson A, Startup R. Nurse socialization: issues and problems. J Adv Nurs. 1991;16(12):1478–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sedory D. Professional socialization. Paper presented at: National Athletic Trainers' Association Athletic Training Educators' Conference; January 13, 2007; Dallas, TX.

- 29.Glaser B.G, Strauss A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. New York, NY: Aldine Publishing Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charmaz K. Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin N.K, Lincoln Y.S, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 509–535. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitney W.A, Parker J. Qualitative research applications in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2002;37(suppl 4):168S–173S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Charon J.M. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurley-Wilson B.A. Socialization for roles. In: Hardy M.E, Conway M.E, editors. Role Theory: Perspectives for Health Professionals. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1988. pp. 73–110. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su J.Z.X. Sources of influence in preservice teacher socialization. J Educ Teach. 1992;18(3):239–258. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pitkala K.H, Mantyranta T. Professional socialization revised: medical students' own conceptions related to adoption of the future physician's role: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):155–160. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000092544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eli I, Shuval J.T. Professional socialization in dentistry: a longitudinal analysis of attitude changes among dental students towards the dental profession. J Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(9):951–955. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dobbs K.K. The senior preceptorship as a method for anticipatory socialization of baccalaureate nursing students. J Nurs Educ. 1988;27(4):167–171. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-19880401-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodman J. University education courses and the professional preparation of teachers: a descriptive analysis. Teaching Teacher Educ. 1986;2(4):341–353. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeichner K.M. Myths and realities: field-based experiences in preservice teacher education. J Teach Educ. 1980;31(11):45–55. [Google Scholar]