Abstract

The multiprotein mTORC1 protein kinase complex is the central component of a pathway that promotes growth in response to insulin, energy levels, and amino acids, and is deregulated in common cancers. We find that the Rag proteins—a family of four related small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases)—interact with mTORC1 in an amino acid sensitive manner and are necessary for the activation of the mTORC1 pathway by amino acids. A Rag mutant that is constitutively bound to GTP interacted strongly with mTORC1 and its expression within cells made the mTORC1 pathway resistant to amino acid deprivation. Conversely, expression of a GDP-bound Rag mutant prevented stimulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. The Rag proteins do not directly stimulate the kinase activity of mTORC1, but, like amino acids, promote the intracellular localization of mTOR to a compartment that also contains its activator Rheb.

The mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) branch of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is a major driver of cell growth in mammals and is deregulated in many common tumors (1). It is also the target of the drug rapamycin, which has generated considerable interest as an anticancer therapy. Diverse signals regulate the mTORC1 pathway, including insulin, hypoxia, mitochondrial function, and glucose and amino acid availability. Many of these are integrated upstream of mTORC1 by the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC1-TSC2) tumor suppressor, which acts as an important negative regulator of mTORC1 through its role as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Rheb, a small guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-binding protein that potently activates the protein kinase activity of mTORC1 (2). Loss of either TSC protein causes hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling even in the absence of many of the upstream signals that are normally required to maintain pathway activity. A notable exception is the amino acid supply, as the mTORC1 pathway remains sensitive to amino acid starvation in cells lacking either TSC1 or TSC2 (3–5).

The mechanisms through which amino acids signal to mTORC1 remain mysterious. It is a reasonable expectation that proteins that signal the availability of amino acids to mTORC1 are also likely to interact with it, but so far no good candidates have been identified. Because most mTORC1 purifications rely on antibodies to isolate mTORC1, we wondered if in previous work antibody heavy chains obscured, during SDS-PAGE analysis of purified material, mTORC1-interacting proteins of 45–55 kD. Indeed, using a purification strategy that avoids this complication (29), we identified the 44 kD RagC protein as co-purifying with overexpressed raptor, the defining component of mTORC1 (6–9).

RagC is a Ras-related small GTP-binding protein and one of four Rag proteins in mammals (RagA, RagB, RagC, RagD). RagA and RagB are very similar to each other and are orthologues of budding yeast Gtr1p whereas RagC and RagD are similar and are orthologues of yeast Gtr2p (10–12). In yeast and in human cells the Rag and Gtr proteins function as heterodimers consisting of one Gtr1p-like (RagA or RagB) and one Gtr2p-like (RagC or RagD) component (13, 14). The finding that RagC co-purifies with raptor was intriguing to us because in yeast Gtr1p and Gtr2p regulate the intracellular sorting of the Gap1p amino acid permease (15) and microautophagy (16), processes modulated by amino acid levels and the TOR pathway (17–19). The Gtr proteins have been proposed to act downstream or in parallel to TORC1 in yeast because their overexpression induces microautophagy even in the presence of rapamycin, which normally suppresses it (16).

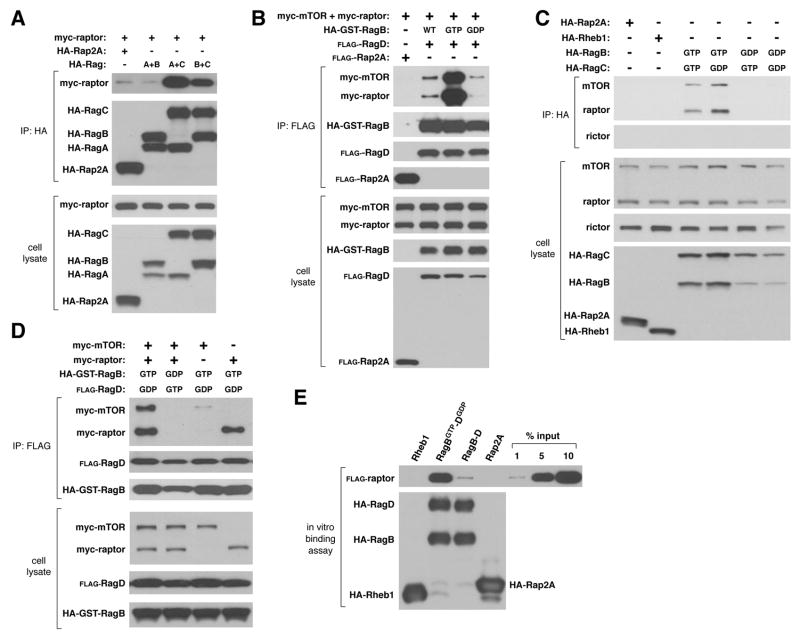

To verify our identification of RagC as an mTORC1 interacting protein, we expressed raptor with different pairs of Rag proteins in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cells. Consistent with the Rags functioning as heterodimers, raptor co-purified with RagA-C or RagB-C, but not with RagA-B or the Rap2A control protein (Fig. 1A). Because the nucleotide loading state of most GTP-binding proteins regulates their functions, we generated RagB, RagC, and RagD mutants predicted (13, 15, 16) to be restricted to the GTP- or GDP-bound conformations (for simplicity we call these mutants RagBGTP, RagBGDP, etc.) (29). When expressed with mTORC1 components, Rag heterodimers containing RagBGTP immunoprecipitated with more raptor and mTOR than did complexes containing wild-type RagB or RagBGDP (Fig. 1B). The GDP-bound form of RagC increased the amount of co-purifying mTORC1, so that RagBGTP-CGDP recovered the highest amount of endogenous mTORC1 of any heterodimer tested (Fig. 1C). Giving an indication of the strength of the mTORC1-RagBGTP-CGDP association, in this same assay we could not detect co-immunoprecipitation of mTORC1 with Rheb1 (Fig. 1C), an established interactor and activator of mTORC1 (1). When expressed alone, raptor, but not mTOR, associated with RagBGTP-DGDP, suggesting that raptor is the key mediator of the Rag-mTORC1 interaction (Fig. 1D). Consistent with this, rictor, an mTOR-interacting protein that is only part of mTORC2 (1), did not co-purify with any Rag heterodimer (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1). Lastly, highly purified raptor interacted in vitro with RagB-D and, to a larger extent, with RagBGTP-DGDP, indicating that the Rag-raptor interaction is most likely direct (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Interaction of Rag heterodimers with recombinant and endogenous mTORC1 in a manner that depends on the nucleotide binding state of RagB. In (A) through (D) HEK-293T cells were transfected with the indicated cDNAs in expression vectors, cell lysates prepared, and lysates and HA- or FLAG-immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting for the amounts of the specified recombinant or endogenous proteins. (E) In vitro binding of purified FLAG-raptor with wild type RagB-D or RagBGTP-DGDP.

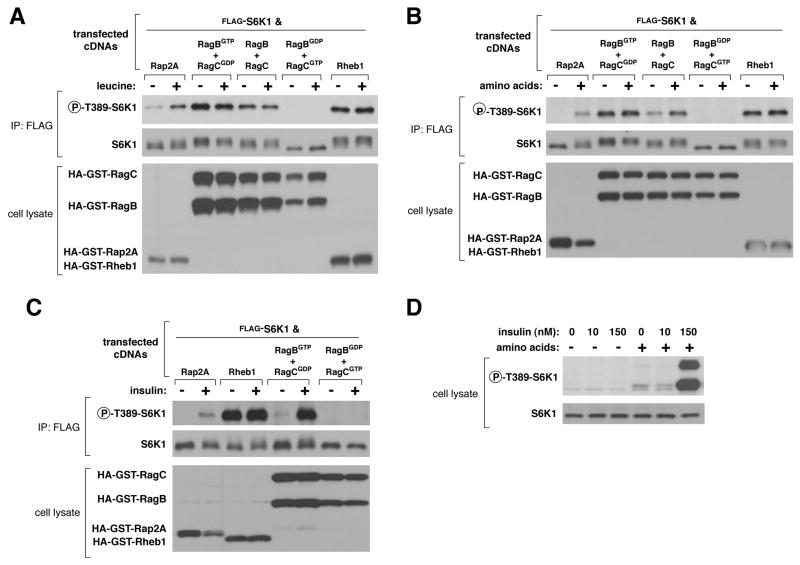

We tested whether various Rag heterodimers affected the regulation of the mTORC1 pathway within human cells. In HEK-293T cells, expression of the RagBGTP-DGDP heterodimer, which interacted strongly with mTORC1, not only activated the pathway but also made it insensitive to deprivation for leucine or total amino acids, as judged by the phosphorylation state of the mTORC1 substrate T389 of S6K1 (Fig. 2A and B). The wild-type RagB-D heterodimer had milder effects than RagBGTP-DGDP, making the mTORC1 pathway insensitive to leucine deprivation, but not to the stronger inhibition caused by total amino acid starvation (Fig. 2A and B). Expression of RagBGDP-DGTP, a heterodimer that did not interact with mTORC1 (Fig. 1C and D), had dominant negative effects, as it eliminated S6K1 phosphorylation in the presence as well as absence of leucine or amino acids (Fig. 2A and B). Expression of RagBGDP alone also suppressed S6K1 phosphorylation (Fig. S2). These results suggest that the activity of the mTORC1 pathway under normal growth conditions depends on endogenous Rag function.

Fig. 2.

Effects of overexpressed RagBGTP-containing heterodimers on the mTORC1 pathway and its response to leucine, amino acids, or insulin. Effects of expressing the indicated proteins on the phosphorylation state of co-expressed S6K1 in response to deprivation and stimulation with (A) leucine, (B) total amino acids, or (C) insulin. Cell lysates were prepared from HEK-293T cells deprived for 50 minutes of serum, and (A) leucine or (B) amino acids, and then, where indicated, stimulated with leucine or amino acids for 10 minutes. HEK-293E cells (C) were deprived of serum for 50 minutes and where indicated stimulated with 150 nM insulin for 10 minutes. Lysates and FLAG-immunoprecipitates were analyzed for the levels of the specified proteins and the phosphorylation state of S6K1. (D) Effects of amino acid deprivation on insulin-mediated activation of mTORC1. HEK-293E cells were starved for serum and amino acids or just serum for 50 minutes, and where specified, stimulated with 10 or 150 nM insulin. Cell lysates were analyzed for the level and phosphorylation state of S6K1.

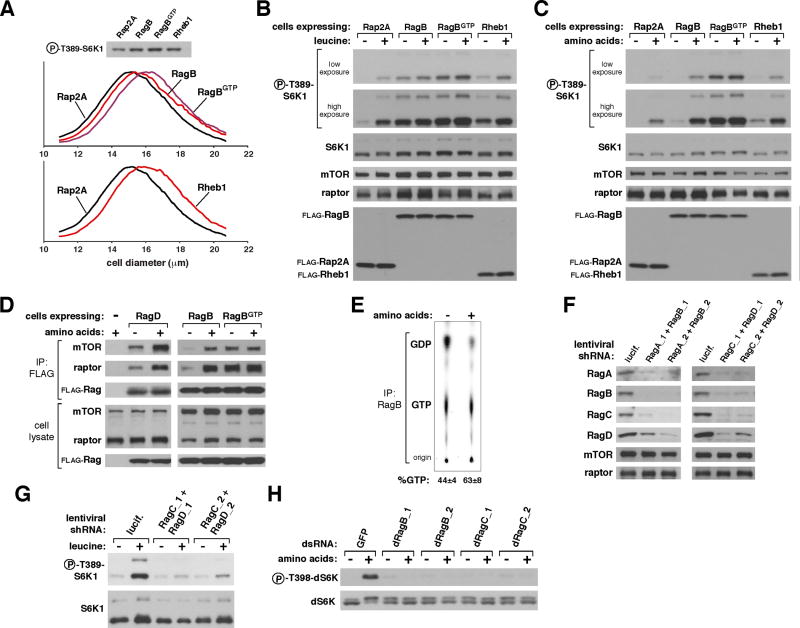

To verify the actions of the Rags in a more physiological setting than that achieved by transient cDNA transfection, we generated HEK-293T cell lines stably expressing Rheb1, RagB, or RagBGTP (attempts to generate lines stably expressing RagBGDP failed). Under normal growth conditions these cells were larger than control cells and had higher levels of mTORC1 pathway activity (Fig. 3A). Unlike transient Rheb1 overexpression (Fig. 2A and B), stable expression did not make the mTORC1 pathway insensitive to leucine or amino acid starvation (Fig. 3B and C), consistent with evidence that transiently overexpressed Rheb may have non-physiological consequences on amino acid signaling to mTORC1 (4, 5). Stable expression of a Rheb1GTP mutant was also unable to make the mTORC1 pathway resistant to amino acid deprivation (Fig. S3). In contrast, stable expression of RagBGTP eliminated the sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway to leucine or total amino acid withdrawal, whereas that of wild-type RagB overcame sensitivity to leucine but not to amino acid starvation (Fig. 3B and C). Thus, transient or stable expression of the appropriate Rag mutants is sufficient to put the mTORC1 pathway into states that mimic the presence or absence of amino acids.

Fig. 3.

Insensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway to amino acid deprivation in cells stably expressing RagBGTP. (A) Cell size distributions (graphs) and S6K1 phosphorylation (immunoblot) of cells stably expressing RagB, Rheb1, RagGTP, or Rap2A. Mean cell diameters ± S.D. (μm) are: Rap2A, 16.05 ± 0.07; Rheb1, 16.79 ± 0.06; RagB, 16.40 ± 0.08; and RagBGTP, 16.68 ± 0.06 (n = 4 and p < 0.0008 for all comparisons to Rap2A-expressing cells). HEK-293T cells transduced with lentiviruses encoding the specified proteins were deprived for 50 minutes for serum and (B) leucine or (C) total amino acids, and, where indicated, re-stimulated with leucine or amino acids for 10 minutes. Cell lysates were analyzed for the levels of the specified proteins and the phosphorylation state of S6K1. (D) Amino acid-stimulated interaction of the Rag proteins with mTORC1. HEK-293T cells stably expressing FLAG-tagged RagB, RagD, or RagBGTP were starved for amino acids and serum for 50 minutes and, where indicated, re-stimulated with amino acids for 10 minutes. Cells were then processed with a chemical cross-linking assay and cell lysates and FLAG-immunoprecipitates analyzed for the levels of the indicated proteins. (E) Effects of amino acid stimulation on GTP loading of RagB. Values are mean ± s.d. for n = 3 (p < 0.02 for increase in GTP loading caused by amino acid stimulation). (F) Abundance of RagA, RagB, RagC, and RagD in HeLa cells expressing the indicated shRNAs. (G) S6K1 phosphorylation in HeLa cells expressing shRNAs targeting RagC and RagD. Cells were deprived of serum and leucine for 50 minutes, and, where indicated, re-stimulated with leucine for 10 minutes. (H) Effects of dsRNA-mediated knockdowns of Drosophila orthologues of RagB or RagC on amino acid-induced phosphorylation of dS6K.

To determine if the Rag mutants affect signaling to mTORC1 from inputs besides amino acids, we tested whether in RagBGTP-expressing cells the mTORC1 pathway was resistant to other perturbations known to inhibit it. This was not the case, as oxidative stress, mitochondrial inhibition, or energy deprivation still reduced S6K1 phosphorylation in these cells (Fig. S4). Moreover, in HEK-293E cells, expression of RagBGTP-DGDP did not maintain mTORC1 pathway activity in the absence of insulin (Fig. 2C). Expression of the dominant negative RagBGDP-DGTP heterodimer did, however, block insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1 (Fig. 2C), as did amino acid starvation (Fig. 2D). Thus, although RagBGTP expression mimics amino acid sufficiency, it cannot substitute for other inputs that mTORC1 normally monitors.

This evidence for a primary role of the Rag proteins in amino acid signaling to mTORC1 raised the question of where, within the pathway that links amino acids to mTORC1, the Rag proteins might function. The existence of the Rag-mTORC1 interaction (Fig. 1), the effects on amino acid signaling of the Rag mutants (Fig. 2 and 3), and the sensitivity to rapamycin of the S6K1 phosphorylation induced by RagBGTP (Fig. S4), strongly suggested that the Rag proteins function downstream of amino acids and upstream of mTORC1. To verify this we took advantage of the established finding that cycloheximide re-activates mTORC1 signaling in cells starved for amino acids by blocking protein synthesis and thus boosting the levels of the intracellular amino acids sensed by mTORC1 (20–22). Thus, if the Rag proteins act upstream of amino acids, cycloheximide should overcome the inhibitory effects of the RagBGDP-CGTP heterodimer on mTORC1 signaling, but if they are downstream, cycloheximide should not reactivate the pathway. The results were clear: cycloheximide treatment of cells reversed the inhibition of mTORC1 signaling caused by leucine deprivation, but not that caused by expression of RagBGDP-CGTP (Fig. S5). Given the placement of the Rag proteins downstream of amino acids and upstream of mTORC1, we determined whether amino acids regulate the Rag-mTORC1 interaction within cells. Initial tests using transiently co-expressed Rag proteins and mTORC1 components did not reveal any regulation of the interaction. Because we reasoned that pronounced overexpression might overcome the normal regulatory mechanisms that operate within the cell, we developed an assay (29), based on a reversible chemical cross-linker, which allows us to detect the interaction of stably expressed FLAG-tagged Rag proteins with endogenous mTORC1. With this approach we readily found that amino acids, but not insulin, promote the Rag-mTORC1 interaction when using either FLAG-tagged RagB or RagD to isolate mTORC1 from cells (Fig. 3D and S6A). As the GTP-loading state of the Rag proteins also regulates the Rag-mTORC1 interaction (Fig. 1), we determined whether amino acids modulate the amount of GTP bound to RagB. Indeed, amino acid stimulation of cells increased the GTP loading of RagB (Fig. 3E). Consistent with this, amino acids did not further augment the already high level of interaction between mTORC1 and the RagBGTP mutant (Fig. 3D).

To determine if the Rag proteins are necessary for amino acids to activate the mTORC1 pathway we used combinations of lentivirally-delivered shRNAs to suppress RagA and RagB or RagC and RagD at the same time. Loss of RagA and RagB also led to the loss of RagC and RagD and vice versa, suggesting that within cells the Rag proteins are unstable when not in heterodimers (Fig. 3F). In cells with a reduction in the expression of all the Rag proteins, leucine-stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1 was strongly reduced (Fig. 3G). The role of the Rag proteins appears to be conserved in Drosophila cells as dsRNA-mediated suppression of the Drosophila orthologues of RagB or RagC eliminated amino acid-induced phosphorylation of dS6K (Fig. 3H). Consistent with amino acids being necessary for activation of mTORC1 by insulin, a reduction in Rag expression also suppressed insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of S6K1 (Fig. S6B). Thus, the Rag proteins appear to be both necessary and sufficient for mediating amino acid signaling to mTORC1.

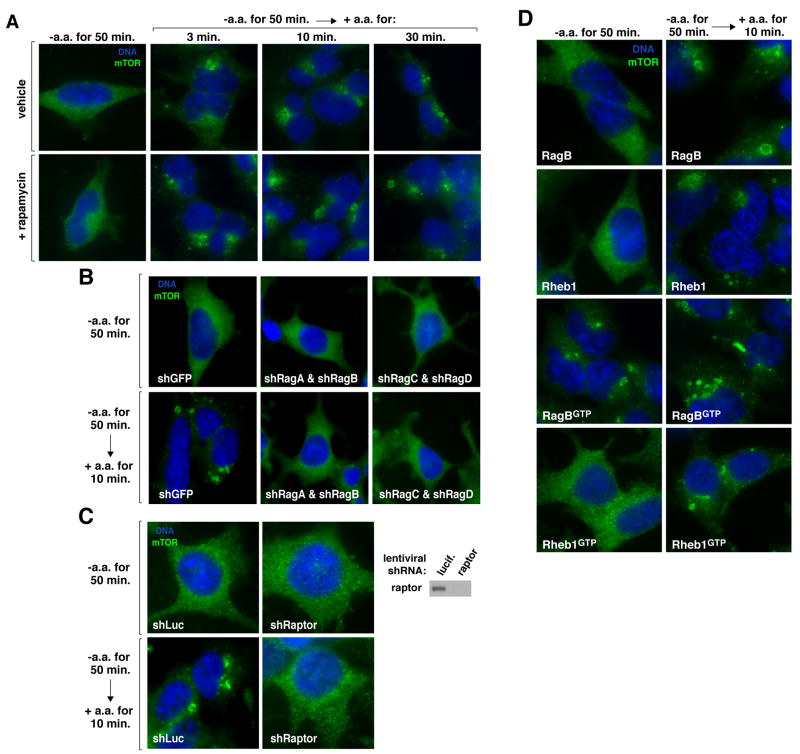

Unlike Rheb (23, 24), the Rag heterodimers did not directly stimulate the kinase activity of mTORC1 in vitro (Fig. S7), so we considered the possibility that the Rag proteins regulate the intracellular localization of mTOR. mTOR is found on the endomembrane system of the cell, including the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and endosomes (25, 26). The intracellular localization of endogenous mTOR, as revealed with an antibody that we validated recognizes mTOR in immunofluorescence assays (Fig. S8), was strikingly different in cells deprived of amino acids than in cells starved and briefly re-stimulated with amino acids (Fig. 4A and S11) or growing in fresh complete media (Fig. S9). In starved cells mTOR was in tiny puncta throughout the cytoplasm, whereas in cells stimulated with amino acids for as little as 3 minutes, mTOR localized to the peri-nuclear region of the cell, to large vesicular structures, or to both (Fig. 4A). Rapamycin did not block the change in mTOR localization induced by amino acids (Fig. 4A), indicating that it is not a consequence of mTORC1 activity but rather may be one of the mechanisms that underlies mTORC1 activation. The amino acid-induced change in mTOR localization required expression of the Rag proteins and of raptor (Fig. 4B and C), and amino acids also regulated the localization of raptor (Fig. S10).

Fig. 4.

Rag-dependent regulation by amino acids of the intracellular localization of mTOR. (A) HEK-293T cells were starved for serum and amino acids for 50 minutes or starved and then re-stimulated with amino acids for the indicated times in the presence or absence of rapamycin. Cells were then processed in an immunofluorescence assay to detect mTOR (green), co-stained with DAPI for DNA content (blue), and imaged. 80–90% of the cells exhibited the mTOR localization pattern shown. (B) and (C) mTOR localization in HEK-293T cells expressing the indicated shRNAs and deprived and re-stimulated with amino acids as in (A). Immunoblot of raptor expression levels. (D) mTOR localization in HEK-293T cells stably expressing RagB, Rheb1, RagBGTP, or Rheb1GTP and deprived and re-stimulated with amino acids as in (A).

In cells overexpressing RagB, Rheb1, or Rheb1GTP, mTOR behaved as in control cells, its localization changing upon amino acid stimulation from small puncta to the peri-nuclear region and vesicular structures (Fig. 4D). In contrast, in cells overexpressing the RagBGTP mutant that eliminates the amino acid sensitivity of the mTORC1 pathway, mTOR was already present on the peri-nuclear and vesicular structures in the absence of amino acids, and became even more localized to them upon the addition of amino acids (Fig. 4D). Thus, there is a correlation, under amino acid starvation conditions, between the activity of the mTORC1 pathway and the subcellular localization of mTOR, implicating a role for Rag-mediated mTOR translocation in the activation of mTORC1 in response to amino acids.

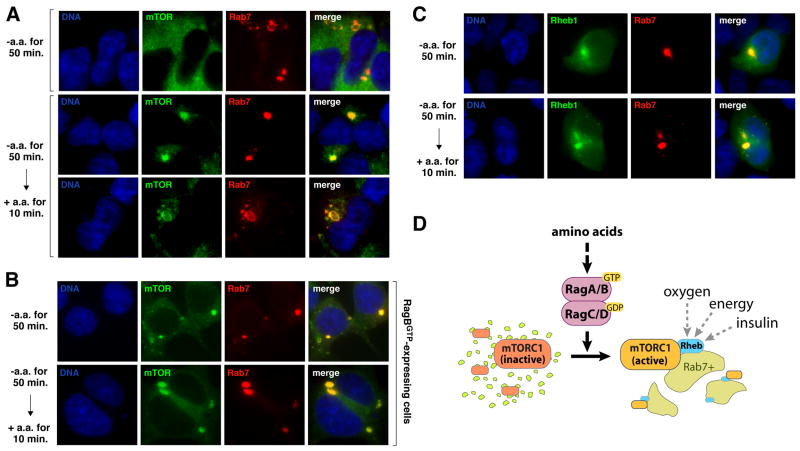

We failed to find an established marker of the endomembrane system that co-localized with mTOR in amino acid starved cells. However, in cells stimulated with amino acids, mTOR in the peri-nuclear region and on the large vesicular structures overlapped with Rab7 (Fig. 5A), indicating that a significant fraction of mTOR translocated to the late endosomal and lysosomal compartments in amino acid replete cells. In cells expressing RagBGTP, mTOR was present on the Rab7-positive structures even in the absence of amino acids (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Amino acids promote the localization of mTOR to a Rab7-positive compartment that also contains Rheb. (A) mTOR and Rab7 localization in cells deprived or stimulated with amino acids. HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with a cDNA for dsRed-Rab7 were starved for serum and amino acids for 50 minutes and, where indicated, stimulated with amino acids for 10 minutes. Cells were then processed to detect mTOR (green), Rab7 (red), and DNA content (blue), and imaged. Two examples are shown of mTOR localization in the presence of amino acids. (B) HEK-293T cells stably expressing RagBGTP and transiently transfected with a cDNA for dsRed-Rab7 were treated and processed as in (A). (C) Rheb1 and Rab7 localization in cells deprived or stimulated with amino acids. HEK-293T cells transiently transfected with 1–2 ng of cDNAs for GFP-Rheb1 and dsRed-Rab7 were treated as in (A), processed to detect Rheb1 (green), Rab7 (red), and DNA content (blue), and imaged. (D) Model for role of Rag GTPases in signaling amino acid availability to mTORC1.

The peri-nuclear region and vesicular structures on which mTOR appears after amino acid stimulation are similar to the Rab7-positive structures where GFP-tagged Rheb localizes in human cells (27, 28). Unlike mTOR, however, amino acids did not appreciably affect the localization of Rheb, as GFP-Rheb1 co-localized with dsRed-Rab7 in the presence or absence of amino acids (Fig. 5C). Unfortunately, it is currently not possible to compare, in the same cells, the localization of endogenous mTOR with that of Rheb because the signal for GFP-Rheb or endogenous Rheb is lost after fixed cells are permeabilized to allow access to intracellular antigens (27, 28). Nevertheless, given that both mTOR and Rheb are present in Rab7-positive structures after amino acid stimulation, we propose that amino acids might control the activity of the mTORC1 pathway by regulating, through the Rag proteins, the movement of mTORC1 to the same intracellular compartment that contains its activator Rheb (see model in Fig. 5D). This would explain why activators of Rheb, like insulin, do not stimulate the mTORC1 pathway when cells are deprived of amino acids, and why Rheb is necessary for amino acid-dependent mTORC1 activation (4) (Fig. S12). When Rheb is highly overexpressed, some might become mis-localized and inappropriately encounter and activate mTORC1, explaining why Rheb overexpression, but not loss of TSC1 or TSC2 makes the mTORC1 pathway insensitive to amino acids (4, 5).

In conclusion, the Rag GTPases bind raptor, are necessary and sufficient to mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1, and mediate the amino acid induced re-localization of mTOR within the endomembrane system of the cell. Given the prevalence of cancer-linked mutations in the pathways that control mTORC1 (1), it is possible that Rag function is also deregulated in human tumors.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

Materials and Methods

References for Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S12

References and Notes

- 1.Guertin DA, Sabatini DM. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byfield MP, Murray JT, Backer JM. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33076–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nobukuni T, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith EM, Finn SG, Tee AR, Browne GJ, Proud CG. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18717–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, et al. Cell. 2002;110:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loewith R, et al. Mol Cell. 2002;10:457–68. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00636-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wedaman KP, et al. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:1204–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hara K, et al. Cell. 2002;110:177–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bun-Ya M, Harashima S, Oshima Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2958–66. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schurmann A, Brauers A, Massmann S, Becker W, Joost HG. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28982–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose E, Nakashima N, Sekiguchi T, Nishimoto T. J Cell Sci. 1998;111( Pt 1):11–21. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakashima N, Noguchi E, Nishimoto T. Genetics. 1999;152:853–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekiguchi T, Hirose E, Nakashima N, Ii M, Nishimoto T. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7246–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004389200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao M, Kaiser CA. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:657–67. doi: 10.1038/ncb1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubouloz F, Deloche O, Wanke V, Cameroni E, De Virgilio C. Mol Cell. 2005;19:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunz JB, Schwarz H, Mayer A. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:9987–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberg KJ, Rowley N, Kaiser CA. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1469–82. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen EJ, Kaiser CA. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:333–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beugnet A, Tee AR, Taylor PM, Proud CG. Biochem J. 2003;372:555–66. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christie GR, Hajduch E, Hundal HS, Proud CG, Taylor PM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9952–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price DJ, Nemenoff RA, Avruch J. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13825–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sancak Y, et al. Mol Cell. 2007;25:903–15. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, Yonezawa K, Avruch J. Curr Biol. 2005;15:702–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drenan RM, Liu X, Bertram PG, Zheng XF. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:772–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mavrakis M, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Stratakis CA, Bossis I. Autophagy. 2007;3:151–3. doi: 10.4161/auto.3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saito K, Araki Y, Kontani K, Nishina H, Katada T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2005;137:423–30. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buerger C, DeVries B, Stambolic V. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:869–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 30.Supported by grants from the NIH (R01 CA103866 and AI47389), Department of Defense (W81XWH-07-0448), and W.M. Keck Foundation to D.M.S. as well as an EMBO fellowship to Y.D.S. We thank T. Kang for the preparation of FLAG-raptor and members of the Sabatini lab for helpful suggestions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.