Abstract

Background

Increasingly, genetic specimens are collected to expand the value of clinical trials through study of genetic effects on disease incidence, progression, or response to interventions.

Purpose and methods

We describe the experience obtaining IRB-approved DNA consent forms across the 19 institutions in the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD), a clinical trial examining the effect of a lifestyle intervention for weight loss on the risk of serious cardiovascular events among individuals with type 2 diabetes. We document the rates participants provided consent for DNA research, identify participant characteristics associated with consent, and discuss implications for genetics research.

Results

IRB approval to participate was obtained from 17 of 19 institutions. The overall rate of consent was 89.6% among the 15 institutions that had completed consenting at the time of our analysis, which was higher than reported for other types of cohort studies. Consent rates were associated with factors expected to be associated with weight loss and cardiovascular disease and to affect the distribution of candidate genes. Non-consent occurred more frequently among participants grouped as African-American, Hispanic, female, more highly educated, or not dyslipidemic.

Limitations

The generalizabilty of results is limited by the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the trial.

Conclusions

Barriers to obtaining consent to participate in genetic studies may differ from other recruitment settings. Because of the potentially complex associations between personal characteristics related to adherence, outcomes, and gene distributions, differential rates of consent may introduce biases in estimates of genetic relationships.

Keywords: Informed consent, genetics, clinical trial

INTRODUCTION

Genetic specimens are often collected within clinical trials to assist in interpreting results and to expand their epidemiological value [e.g. Lavori, 2003]. Because of the ancillary role of genetic research in these situations, and because volunteers may have additional concerns about allowing DNA testing, it is common that consent for DNA testing is not required for participation in the clinical trial. Genetic analyses are limited to the subset of participants who provide this separate consent. Because this selfselection is non-random, results from these genetic analyses may be compromised by biases. In multi-center studies, consent language may vary according to institutional practices and interpretations, which may result in differential participation among sites and further hamper these genetic studies and subsequent analyses.

We describe the experience in obtaining DNA consent across the 19 institutions participating in the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) clinical trial. We document the overall rates of agreement among participants, identify participant characteristics associated with full and partial consent, and discuss implications of our findings for genetics research.

METHODS

Study design

Look AHEAD is a multi-center randomized clinical trial that has enrolled 5,145 overweight or obese volunteers with type 2 diabetes [Look AHEAD, 2003]. It has been designed to assess the long-term effects on cardiovascular outcomes of an intensive lifestyle intervention program designed to achieve and maintain weight loss by decreased caloric intake and increased physical activity. This intervention program is being compared to a program of diabetes support and education.

Look AHEAD participants have type 2 diabetes and at enrollment were aged 45−75 years and overweight or obese (body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2, or ≥ 27 kg/m2 if on insulin). Other inclusion criteria were having a source of medical care, blood pressure <160/100 mmHg (treated or untreated), HbA1c <11%, plasma triglycerides < 600 mg/dl, and willingness to accept random assignment and participate in the study for the proposed 11.5 years. Potential volunteers who were judged to be unlikely to be able to carry out the components of the weight loss intervention were excluded. Enrollment activities began in June, 2001 and were completed in March, 2004.

Goals of the DNA collection

The collection and storage of specimens for genetic analyses were included in the Look AHEAD protocol to enable investigators to explore candidate genes as mediators and modifiers of how weight loss affects outcomes associated with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other comorbidities related to obesity. Hypotheses related to these samples were not specified in the primary study protocol, but were expected to be developed as ancillary studies.

Development of genetic informed consent document

It was recognized during the development of Look AHEAD that consent to provide specimens for genetic testing would require special attention and procedures. Because of this, a model consent form for the genetic substudy (Appendix A), which was separate from the consent form for participation in the clinical trial, was developed based on published guidelines [Clayton, 1995; Beskow et al., 2001]. Clinical sites tailored this model according to local practices and institutional review board rulings; at some sites, consent for genetic testing was merged into the main consent document for the clinical trial. However, at all sites consent was separate from and not required for clinical trial participation.

Consent procedures for the Look AHEAD Genetic Substudy

Trained clinic staff provided the following information:

the purpose of obtaining samples;

steps taken to protect the participant's confidentiality and privacy in terms of how samples and records will be managed and research presented;

a description of how samples will be controlled and the statement that participants will not receive profits from any products produced from their samples;

procedures by which participants may withdraw permission at a later date;

the length of time samples will be stored; and

that results of individual genetic testing will not be available to participants.

The participant was allowed to read the consent form in private. If the participant declined to participate in the genetic substudy, this was noted in the participant's source documents. If a witnessed and signed consent was obtained, a copy of the form was given to the participant and two 10 ml blood samples were drawn.

Baseline data collection, variable definitions, and data analysis plans

We assembled a range of factors to serve as markers of health, culture, demography, and lifestyle. We wished to explore whether there was evidence that consent rates differ according to these attributes. Thus, while we include hypertension among the factors we examine, we view it more generally as a marker of health, rather than a specific medical condition. In some cases, however, the factors we have selected also allow us to confirm associations described by others researchers.

Data on factors were collected by standardized questionnaires, either self- or staff-administered, or by clinical measures obtained from trained and certified technicians, as discussed in greater detail elsewhere [Look AHEAD, 2003]. History of hyperlipidemia was defined as either a measured low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) >130 mg/dl and/or use of a lipid lowering agent. Fitness was assessed using a standardized maximum graded exercise test and expressed as metabolic equivalents (METs): 1.0 MET equals 3.5 ml of oxygen uptake per kilogram of body weight per minute.

We use definitions of ethnicity and race adopted by the US Census Bureau. A selfadministered questionnaire collected responses on Latino/Hispanic/Spanish origin (yes/no) and separately racial group (African-American/Black, American Indian/Native American/Alaskan Native; Asian/Pacific Islander, White, or Other). In our analyses, we assigned all individuals responding positively about Latino origin to one racial/ethnic group and the remaining individuals to the racial/ethnic group they selected; individuals selecting more than one race were assigned to the racial category “Other.” As with other factors, our intention was not to use these responses to examine relationships between consent and specific racial/ethnic groups, but to use these responses to explore whether rates of consent varied across the broader social and cultural milieu linked to these designations [e.g. Jones, 2001].

The final DNA consent forms for Look AHEAD varied among sites and are posted at http://lookahead.phs.wfubmc.edu. We grouped forms according to whether only unconditional consent was requested or whether consent could be restricted according to qualifying conditions, such as limiting access to study investigators or barring the development of cell lines. The exact wording of these qualifiers appears on this website.

Univariable and multivariable associations between factors and levels of consent were examined with logistic regression. Backward and forward stepwise logistic regression were used to identify subsets of factors that appeared jointly to have important relationships with agreement; these produced identical results in all analyses we report. Model fit was assessed with influence plots [SAS, 2004]. Because many factors were inter-related, these approaches may not have characterized the full expression of all important multivariate relationships. Analyses were limited to institutions for which IRB-approval and the consent process had been completed by March 1, 2005; the two sites receiving late approval were excluded because consenting participants was still ongoing.

RESULTS

Obtaining consent at clinical centers

Of the 19 institutions that enrolled Look AHEAD participants, 17 obtained IRB approval to participate in the genetics substudy and are listed in Table 1. In some cases, approval required repeated revisions of applications, separate approval from more than one institutional review board, negotiations between the NIH and The Veterans Health Administration, and/or resolution of a temporary institution-wide suspension of research. These complications delayed collection of genetic materials on some participants for as long as two years after randomization.

Table 1.

Approved DNA consent language, levels of consent, and stage of screening presented to participant.

| Institution | Qualified vs. Unconditional Consent? |

|---|---|

| Baylor College of Medicine | Unconditional |

| Brown University | 5 possible qualifiers |

| Joslin Diabetes Center* | 5 possible qualifiers |

| Massachusetts General Hospital* | 5 possible qualifiers |

| Pennington Biomedical Research Center | 6 possible qualifiers |

| St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Center | 3 possible qualifiers |

| Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix** | Unconditional |

| Southwestern American Indian Center, Sacaton** | Unconditional |

| The University of Alabama at Birmingham | Unconditional |

| The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions | Unconditional |

| The University of Tennessee at Memphis*** | 6 possible qualifiers |

| University of Colorado Health Sciences Center | 6 possible qualifiers |

| University of Minnesota | 6 possible qualifiers |

| University of Pennsylvania | 3 possible qualifiers |

| University of Pittsburgh | 5 possible qualifiers |

| University of Texas at San Antonio | 8 possible qualifiers |

| University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System | Unconditional |

The clinical site at the Joslin Diabetes Center was administered as a subcontract to the Massachusetts General Hospital

The Southwestern American Indian sites were centrally administrated by the Phoenix Center

Two separate clinical sites were operated by the University of Tennessee at Memphis

Rates of consent within Look AHEAD

Only unconditional consent (yes/no) was requested at 6 of the 17 institutions with IRB approval; the remaining allowed conditions to be attached to consent, which varied from three to eight separate qualifiers (Table 1). These qualifiers contained language allowing participants to restrict access and use of samples, prevent samples being used for the personal financial gain of investigators, and deny the development of cell lines.

Table 2 provides the proportions of subjects who agreed to participate at least in some level (i.e. fully or conditionally) in the DNA study across the factors we examined in the 15 of 17 institutions that had completed consenting by March 1, 2005. Overall, this rate was 3583/3996 = 89.7% and was higher among the 3 institutions that embedded consent within the same document as for the main trial 432/451= 95.8%, compared to the remaining institutions. We found the following markers were most strongly associated with differences in rates of agreement: race/ethnicity, education, hyperlipidemia, sex, and history of cardiovascular disease. Consent rates tended to be lower among participants grouped as African-American and Hispanic than among those grouped as Asian and White. It was also lower among those with 17 or more years of education, among women, and those without hyperlipidemia or without a history of cardiovascular disease. Based on univariable analyses, none of the lifestyle-related characteristics we examined (smoking, fitness, or weight) was associated with an agreement to have samples stored.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants enrolled in Look AHEAD grouped by whether they provided at least some level of consent to participate in DNA studies (limited to clinics having IRB approval to conduct study), which overall was 89.7%.

| Characteristic | N | Percent Providing Consent | Uniformity Across All Subgroups p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years with diabetes | |||

| <5 | 1848 | 89.1% | |

| 5−9 | 1094 | 89.8% | 0.43 |

| 10+ |

1054 |

90.5% |

|

| CVD history | |||

| No | 3408 | 89.3% | 0.05 |

| Yes |

588 |

91.8% |

|

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 712 | 89.7% | 0.92 |

| Yes |

3284 |

89.6% |

|

| Hyperlipidemia | |||

| No | 1289 | 88.2% | 0.01 |

| Yes |

2707 |

90.3% |

|

| HbA1c | |||

| <7.0% | 1839 | 88.9% | |

| 7.0−8.9% | 1796 | 90.4% | 0.37 |

| 9.0−10.9% |

361 |

90.0% |

|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 2341 | 88.5% | 0.02 |

| Male |

1655 |

91.3% |

|

| Age, yrs | |||

| 45−54 | 965 | 88.7% | |

| 55−64 | 2177 | 89.4% | 0.11 |

| 65−75 |

853 |

91.2% |

|

| Education, yrs | |||

| <13 (high school) | 656 | 89.3% | 0.01 |

| 13−16 (college) | 1552 | 91.5% | |

| ≥17 (graduate school) |

1698 |

88.0% |

|

| Ethnicity | |||

| Latino | 352 | 87.5% | 0.08 |

| Non-Latino |

3638 |

89.9% |

|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| African-American | 666 | 81.7% | |

| American Indian | 154 | 90.3% | |

| Asian | 30 | 100.0% | <0.001 |

| White | 2706 | 91.9% | |

| Hispanic | 352 | 87.5% | |

| Other/Multiple |

82 |

84.1% |

|

| Family Income | |||

| <$25,000 | 338 | 90.2% | |

| $25−49,999 | 1517 | 91.4% | 0.66 |

| $50,000+ |

1706 |

90.3% |

|

| Cigarette smoking | |||

| Never | 1960 | 89.1% | |

| Former | 1847 | 90.0% | 0.59 |

| Current |

175 |

90.9% |

|

| Fitness, METS | |||

| <5 | 464 | 88.8% | |

| 5−9 | 3154 | 89.9% | 0.74 |

| 10+ |

378 |

88.4% |

|

| BMI, kg/m2 | |||

| 25−29 | 578 | 88.1% | |

| 30−34 | 1356 | 89.2% | 0.34 |

| 35+ | 2056 | 90.4% |

Table 3 presents results from stepwise logistic regression analyses applied to the factors in Table 2 to identify multivariable predictors of full, unconditional consent. The algorithm selected sex and race/ethnicity as being the strongest independent predictors; no other factors had strong relationships with consent after covariate adjustment for sex and race/ethnicity. Relative to men, the odds ratio for women agreeing to participate was 0.68 [95% confidence interval: 0.58, 0.80]. Compared to Caucasian participants, African-American participants had an odds ratio of 0.46 [0.38, 0.57] and Hispanic participants had an odds ratio of 0.58 [0.42, 0.80]. The other racial/ethnic groups were small, leading to imprecise estimates of their effects.

Table 3.

Factors selected by stepwise logistic regression as independent predictors of full consent to participate in the DNA substudy, after adjusting for differences among clinical centers (limited to sites permitting qualified consent). All factors listed in Table 2 were available for selection.

| Factor |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

Uniformity Across All Subgroups p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 0.68 [0.58, 0.80] | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.00 | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African-American | 0.46 [0.38, 0.57] | |

| American Indian | 1.80 [0.36, 3.21] | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.83 [0.35, 1.97] | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 0.58 [0.42, 0.80] | |

| Other/Multiple | 0.74 [0.43, 1.27] | |

| White | 1.00 |

Table 4 examines degrees of participation among the subsets of institutions that allowed for conditional agreement for the use of samples by other investigators or future studies, or to develop cell lines. Presented are results from stepwise logistic regression. Factors selected to be associated with lower rates of agreement for specimens to be used by other investigators were race/ethnicity (African-American and Hispanic) and higher education. Lower rates of agreement for specimens to be used by future studies were most strongly associated with race/ethnicity (African-American and Hispanic), higher education, and female sex. Lower rates of agreement for use of specimens to develop cell lines were associated with race/ethnicity (African-American) and younger age. Women were less likely to allow their samples to be used for purposes resulting in financial gain than men.

Table 4.

Among the subsets of clinics allowing partial consent for specific uses: factors selected by stepwise logistic regression as being associated with consent, after adjustment for differences among clinics

| Permission for use by other investigators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor (Overall Agreement Rate, %) |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African-American (76.5%) | 0.41 [0.31, 0.53] | |

| American Indian (85.0%) | 0.50 [0.14, 1.88] | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (86.7%) | 0.91 [0.29, 2.87] | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (82.8%) | 0.51 [0.34, 0.75] | |

| Other/Multiple (85.7%) | 0.72 [0.34, 1.53] | |

| White (90.1%) | 1.00 | |

| Education, yrs | ||

| <13 (86.9%) | 1.54 [1.20, 1.97] | 0.003 |

| 13−16 (89.3%) | 1.27 [0.94, 1.74] | |

| 17+ (84.6%) | 1.00 | |

| Permission for use by future studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor (Overall Agreement Rate, %) |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| African-American (76.5%) | 0.44 [0.33, 0.58] | |

| American Indian (85.0%) | 0.54 [0.14, 2.04] | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander (86.7%) | 0.98 [0.31, 3.08] | <0.001 |

| Hispanic (82.5%) | 0.52 [0.35, 0.77] | |

| Other/Multiple (85.7%) | 0.74 [0.35, 1.56] | |

| White (90.1%) | 1.00 | |

| Education, yrs | ||

| <13 (86.9%) | 1.60 [1.25, 2.05] | <0.001 |

| 13−16 (89.6%) | 1.35 [0.99, 1.84] | |

| 17+ (84.6%) | 1.00 | |

| Sex | ||

| Female (85.0%) | 0.75 [0.59, 0.94] | 0.01 |

| Male (89.6%) | 1.00 | |

| Permission for development of cell lines | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor (Overall Agreement Rate, %) |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||

| African-American (73.6%) | 0.42 [0.32, 0.56] | |

| American Indian (82.3%) | 0.52 [0.15, 1.84] | |

| Hispanic (85.0%) | 0.66 [0.43, 1.01] | <0.001 |

| Other/Multiple (82.1%) | 1.77 [1.01, 3.08] | |

| White (86.9%) | 1.00 | |

| Age, yrs | ||

| 45−54 (81.7%) | 0.61, [0.45, 0.84] | |

| 55−64 (84.3%) | 0.78 [0.59, 1.03] | 0.03 |

| 65−75 (88.5%) | 1.00 | |

| Permission to allow samples to be used for the financial gain of investigators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor (Overall Agreement Rate, %) |

Odds Ratio [95% CI] |

p-value |

| Sex | ||

| Female (46.3%) | 0.36 [0.24, 0.53] | <0.001 |

| Male (70.0%) | 1.00 | |

All those in the Asian subgroup consented

DISCUSSION

Rates of consent

Among the DNA study sites, the willingness to consent was widespread (89.7% across institutions), which was greater than several cohort studies have reported. For example, consent to provide buccal cell samples in the large adult Agricultural Health Study was obtained from 79% of those contacted, and samples were ultimately provided by only 75% of those agreeing to participate [Engel, 2002]. The Smokers and Nonsmokers Study reported that 57% of individuals contacted by phone agreed to receive a buccal swab kit, and of these only 46% returned specimens [Kozlowski, 2002]. Buccal samples for genetic testing were provided by 67% of the Multiethnic Cohort Study [Le Marchand, 2001]. Among adults completing NHANES interviews, 84% and 85% agreed to participate in DNA studies in 1999 and 2000 respectively [McQuillan, 2003]. The greater willingness of Look AHEAD participants to join its DNA study may be attributable to the prior willingness of these individuals to consent to the elaborate and prolonged screening process to establish study eligibility [Look AHEAD, 2003] and by participation in the trial. It may also have been enhanced by the rapport established between study staff and potential participants through its extensive screening process the extended contacts involved in establishing study eligibility and obtaining baseline data.

Factors associated with consent

Much has been written about general correlates of participation in medical research [e.g. Lovato, 1997]. Participation is thought to be influenced by personal demographics, health status, risk factors, and socio-cultural dimensions [e.g. Wyatt, 2003]. Much less has been written that is specific to participation in genetic studies. The Smokers and Nonsmokers Study reported that consent to receive buccal swab kits was higher among individuals who were better educated, younger, current smokers, and who had symptoms of depression; within this subset, the rate of consent for DNA collection was higher among individuals who were older, better-educated, White, and non-smokers [Kozlowski, 2002]. NHANES researchers reported that consent rates for participating in DNA research were lower among African-Americans and women [McQuillan, 2003]. Researchers in the Agricultural Health Study reported that there were only minor differences in demographic, lifestyle, disease, and occupational factors between farmers who consented and those who did not consent to participate in a genetics study [Engel, 2002]. These three reports are based on cohort studies, and thus cannot make the more focused contrast between characteristics of participants who consent within the context of a clinical trial. Further, none of these studies has the rich source of participant phenotypic characteristics provided by the Look AHEAD baseline database. None addresses varying levels of consent for use of genetic samples.

Similar to other cohort studies, we found that the strongest correlates of DNA study consent were markers of socio-demographic and cultural attributes [Engel, 2002; Kozlowski, 2002; McQuillan, 2003]. These included race/ethnicity (with lower rates among African-Americans and Latinos), sex (with lower rates among women), and education (with lower rates among more highly educated individuals).

Participation in medical research is often lower among members of minority racial/ethnic groups and the challenges of recruiting these individuals are well documented [e.g. El-Sadr, 1992; Shavers, 2002; Stoddart, 2000; Wyatt, 2003]. Individuals from traditional racial/ethnic minority groups compromise 36.8% of the Look AHEAD cohort; this figure exceeds the study goal that was set during protocol development. The relatively lower rates of consent among African-American and Hispanic participants to join the genetic sub-study indicate that additional focus may be required to cultivate participation of these individuals in genetic studies.

The differences we saw related to gender and education were unexpected. In general, women are found at least as likely to participate in clinical trials as men [Lovato, 1997; Haddock, 2002], however this is not universal [Gorkin, 1996]. In Look AHEAD, the percentage of women enrollees approached the maximum set in the protocol (60%) and women were no more likely than men to drop out during screening. Yet, women in Look AHEAD had lower levels of overall consent for the genetics study than men and were less likely to approve the storage and subsequent use of DNA and to provide permission for samples to be sold. Higher levels of education have been reported to be associated with greater participation in genetic studies and clinical trials [e.g. Cappelli, 2002; Rimer, 1996]. Although attempts were made to reduce barriers related to education during recruitment, the Look AHEAD cohort is more highly educated than the general US population, with over 80% of its members having at least some college education. We were surprised to find that the more highly educated of these participants were less likely to consent to a genetic study, and more likely to attach conditions to their consent. Further study is required to determine which features of the consent process and/or study goals were of concern to the most highly educated of the cohort.

The markers of health status we examined were generally not strongly associated with agreement to consent. The trends that were evident for history of cardiovascular disease and hyperlipidemia indicated that individuals with chronic health problems were at least as agreeable to participate as other subjects. This stands in contrast to the general experience that volunteers for clinical research tend to be healthier than non-volunteers [e.g. Walker, 1987; Lindsted, 1996; Froom, 1999], and from the experience within Look AHEAD that its participants are more healthy than the general population of individuals with diabetes. Look AHEAD participants may be individuals with greater concern with personal health, which has been linked to greater levels of consent to participate in clinical trials [Gorkin, 1996].

Potential impact of non-consent on findings

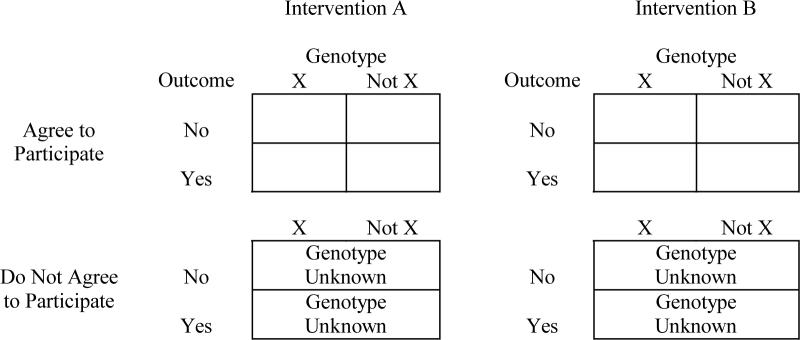

In most clinical trials, DNA studies are collected to examine the role that genes may have in influencing responses to interventions, i.e. three-way associations between genes, interventions, and outcomes. Our analyses indicate it is plausible that levels of consent may vary among subgroups jointly defined by these factors. For example, intervention adherence, outcome risk, and genetic distributions each may vary by race/ethnicity, as do rates of consent. Consider the following four-way table in Figure 1. Genetic data are not available for the lower panel of cells; however, one would expect in clinical trials that intervention assignment and outcome data would be available.

Figure 1.

Observed and unobserved data associated with non-consent.

If genetic data are missing completely at random, the lower panels of Figure 1 may be ignored in analyses. If agreement to participate is related to the intervention, outcome, and/or genotype, ignoring this panel may result in bias. In such cases, it may be possible to develop models that statistically account for these relationships. The breadth of data available in many clinical trials enhance the potential that such models may be found. If successful, this approach yields data that are “missing at random,” for which many analytical approaches are appropriate [e.g. Little and Rubin, 2002]. If data are missing at random and if consent rates are fairly high, estimation bias can be controlled to be relatively modest through the use of statistical methods [e.g. Fitzmaurice, 2001]. If models cannot be found to account for relationships, missing data are non-ignorable. In such cases, expected bias is related to the rate of consent and the strength of associations causing the non-ignorability [e.g. Zhao, 1996].

Sensitivity analyses may be used to examine the potential breadth of biases. As an example of these, we examined a situation in which the odds ratio relating an outcome to intervention assignment was 2.0 for individuals with and without Genotype X (which we assumed had prevalence of 50%), so that the ratio of the genotype-specific odds ratios was 1.00. In this example, we assume dominance (rather than additivity) of allelic effects, so that there are only two genotypes of interest (e.g., 11 or 12 vs. 22, if allele 1 is dominant to 2). We also examined the situation when the ratio (genotype X vs genotype Not X) of these odds ratios was 4.0 (i.e. the odds ratio was 4.0 for genotype X and 1.0 for genotype Not X).

What would happen if we randomly withdrew 15% of genotype X and 5% of genotype Not X (as if they were non-consenters), so that the consent rates were not independent of genotype, and analyses were conducted only on the remainder of the cohort? We examined several sampling mechanisms related to non-consent, allowing the relationship between intervention and outcome to vary between genotypes among nonconsenters from the overall values (Table 5). The range of assumptions related to nonignorable missing data we examined was sufficient to introduce biases ranging from −19.9% to 26.5%. The lost efficiency of inference (on the log-linear contrast relating the genotype x treatment x outcome interaction) was uniformly about 10%. For example, if the relationship between the intervention and outcomes had an odds ratio of 4.0 among individuals with genotype X and an odds ratio of 1.0 for individuals without this genotype, and if the intervention was not associated with outcomes among nonconsenters regardless of genotype, then under the assumptions of our simulation, an analysis limited to consenters would be expected to over-estimate the overall odds ratio by 15.9%.

Table 5.

Expected relative bias and efficiency associated with non-consent, which is assumed to occur at a rate of 15% for individuals with Genotype X and 5% among others. Both Genotype X and the outcomes are assumed to have prevalence of 50%. Odds ratios are for associations between the outcome and intervention assignment.

| Ratio of Gene-Specific ORs For Full Cohort |

OR Between Intervention And Outcome Among Non-consenters |

Results From Analysis of Consenters Only |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype X |

Genotype Not X |

Observed Ratio of ORs |

Standard Error of Observed Ratios of ORs |

Relative Bias (%) |

Relative Efficiency* (%) |

|

| 1.00 | 1.000 | 0.126 | 0.0 | 89.9 | ||

| 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.039 | 0.131 | 3.9 | 89.9 | |

| 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.077 | 0.136 | 7.7 | 89.9 | |

| (Assumed to be 2.00 in genotype X and in others) | 1.00 | 0.892 | 0.112 | −10.8 | 89.9 | |

| 2.00 | 2.00 | 0.927 | 0.117 | −7.3 | 89.9 | |

| 4.00 | 0.960 | 0.121 | −4.0 | 89.9 | ||

| 1.00 | 0.801 | 0.101 | −19.9 | 89.9 | ||

| 4.00 | 2.00 | 0.832 | 0.105 | −16.8 | 89.9 | |

| |

|

4.00 |

0.862 |

0.109 |

−13.8 |

89.9 |

| 1.00 | 4.638 | 0.594 | 15.9 | 89.4 | ||

| 4.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 4.872 | 0.625 | 21.8 | 89.2 |

| 4.00 | 5.058 | 0.649 | 26.5 | 89.0 | ||

| (Assumed to be 4.00 in genotype X and 1.0 among others) | 1.00 | 4.160 | 0.531 | 4.0 | 89.9 | |

| 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.328 | 0.553 | 8.2 | 89.7 | |

| 4.00 | 4.492 | 0.575 | 12.3 | 89.6 | ||

| 1.00 | 3.723 | 0.474 | −6.9 | 90.3 | ||

| 4.00 | 2.00 | 3.872 | 0.494 | −3.2 | 90.1 | |

| 4.00 | 4.018 | 0.513 | 0.0 | 90.0 | ||

Square of the ratio of standard errors for the log-linear contrast defined by the 3-way interaction involving genotype, intervention, and outcome

Similar calculations may be developed for other scenarios to understand the potential ramifications of potential patterns of non-consent. Use of analytical methods that address missing data would be required to reduce expected bias in estimates.

CONCLUSIONS

It was very useful for Look AHEAD to develop and circulate a model consent form for tailoring across sites. In turn, it was very useful to this process to have published guidelines [Clayton, 1995; Beskow, 2001]. As experience with genetic research accrues across institutional review boards, it may be that greater uniformity in acceptable language will be facilitated.

Two Look AHEAD institutions did not participate in the genetics substudy, which has resulted in the loss of potential participants and statistical power. Because these data are missing due to structural, rather than participant-specific, reasons and because randomization was stratified by clinical site so that these missing data are uniformly distributed across interventions, the chance that this loss will introduce bias in study findings related to the study intervention is low. However, the degree to which nonparticipating sites may represent special populations limits the generalizability of findings.

We found that rates of consent for genetic studies among participants already enrolled in Look AHEAD were much higher than those observed for participants in other cohort studies. We also found that factors associated with consent among these participants differed from what might be expected from literature on volunteerism for medical studies: participation in genetics studies may be higher among those with less education, among men, and possibly among those who are less healthy. These findings suggest that the process of obtaining consent to participate in genetic studies among clinical trial participants may face a set of barriers that differs from other recruitment settings. Because of the potentially complex associations between personal characteristics related to adherence, outcomes, and gene distributions, it is critical to consider the fact that differential rates of consent may introduce biases in estimates of genetic relationships.

Roster of Look AHEAD sites and staff

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Frederick Brancati, MD, MHS; Debi Celnik, MS, RD, LD; Jeanne Clark, MD, MPH; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Lawrence Cheskin, MD; Kerry Stewart, EdD; Richard Rubin, PhD; Kathy Horak, RD

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD; Kristi Rau; Allison Strate, RN; Frank L. Greenway, MD; Donna H. Ryan, MD; Donald Williamson, PhD; Elizabeth Tucker; Brandi Armand, LPN; Mandy Shipp, RD; Kim Landry; Jennifer Perault

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Sheikilya Thomas MPH; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Monika Safford, MD; Stephen Glasser, MD; Clara Smith, MPH; Cathy Roche, RN; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Nita Webb, MA; Staci Gilbert, MPH; Amy Dobelstein; L. Christie Oden; Trena Johnsey

Harvard Center Massachusetts General Hospital: David M. Nathan, MD; Heather Turgeon, RN; Kristina P. Schumann, BA; Enrico Cagliero, MD; Kathryn Hayward, MD; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD; Barbara Steiner, EdM; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Alan McNamara, BS; Richard Ginsburg, PhD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, MS; Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD; A. Enrique Caballero, MD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Lori Lambert, MS, RD Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc; Ann McNamara, RN; Heather McCormick, RD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center James O. Hill, PhD; Marsha Miller, MS, RD; Brent VanDorsten, PhD; Judith Regensteiner, PhD; Robert Schwartz, MD; Richard Hamman, MD, DrPH; Michael McDermott, MD; JoAnn Phillipp, MS; Patrick Reddin, BA; Kristin Wallace, MPH; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; April Hamilton, BS; Salma Benchekroun, BS; Susan Green; Loretta Rome, TRS; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD; Henry Pownall, PhD; Peter Jones, MD; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MD; Molly Gee, MEd., RD

University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Mohammed F. Saad, MD; Ken C. Chiu, MD; Siran Ghazarian, MD; Kati Szamos, RD; Magpuri Perpetua, RD; Michelle Chan, BS; Medhat Botrous

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH; Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN; Leeann Carmichael, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP; John P. Bantle, MD; J. Bruce Redmon, MD; Richard S. Crow, MD; Jeanne Carls, Med; Carolyne Campbell; La Donna James; T. Ockenden, RN; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; M. Patricia Snyder, MA, RD; Amy Keranen, MS; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD; Emily Finch, MA; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Tricia Skarphol, BS

St. Luke's Roosevelt Hospital Center Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD; Jennifer Patricio, MS; Jennifer Mayer, MS; Stanley Heshka, PhD; Carmen Pal, MD; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE; Gary D. Foster, PhD; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD; Stanley Schwartz, MD; Shiriki K Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH; Monica Mullen, MS, R.D; Louise Hesson, MSN; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Canice Crerand, PhD; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Ray Carvajal, MS; Renee Davenport; Helen Chomentowski

University of Pittsburgh David E. Kelley, MD; Jacqueline Wesche -Thobaben, RN,BSN,CDE; Lewis Kuller, MD, DrPH.; Andrea Kriska, PhD; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD; Mary L. Klem, PhD,MLIS; Janet Bonk,RN,MPH; Jennifer Rush, MPH; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Barb Elnyczky, MA; Karen Vujevich, RN-BC, MSN, CRNP; Janet Krulia, RN, BSN, CDE; Donna Wolf, MS; Juliet Mancino, MS,RD, CDE, LDN; Pat Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Anne Mathews, MS, RD, LDN

Brown University Rena R. Wing, PhD; Vincent Pera, MD; John Jakicic, PhD; Deborah Tate, PhD; Amy Gorin, PhD; Renee Bright, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Tammy Monk, MS; Kara Gallagher, PhD; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Maureen Daly, RN; Tatum Charron, BS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Linda Foss, MPH; Deborah Robles; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; Caitlin Egan, MS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Don Kieffer, PhD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Jane Tavares, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; JP Massaro, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steve Haffner, MD; Maria Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE; Connie Mobley, PhD, RD; Carlos Lorenzo, MD

University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB; Brenda Montgomery, MS RN CDE; Robert H. Knopp, MD;Edward W. Lipkin, MD, PhD; Matthew L. Maciejewski, PhD; Dace L. Trence, MD; Roque M. Murillo, BS;S Terry Barrett, BS

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH; Paula Bolin, RN, MC; Tina Killean, BS; Carol Percy, RN; Rita Donaldson, BSN; Bernadette Todacheenie, EdD; Justin Glass, MD; Sarah Michaels, MD; Jonathan Krakoff, MD; Jeffrey Curtis, MD, MPH; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP; Tina Morgan; Ruby Johnson; Cathy Manus; Janelia Smiley; Sandra Sangster; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Minnie Roanhorse; Didas Fallis, RN; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP; Leigh Shovestull, RD

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University School of Medicine Mark A. Espeland, PhD; Judy Bahnson, BA; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH; David Reboussin, PhD; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD; Wei Lang, PhD; Alain Bertoni, MD, MPH; Mara Vitolins, DrPH; Gary Miller, PhD; Paul Ribisl, PhD; Kathy Dotson, BA; Amelia Hodges, BA; Patricia Hogan, MS; Kathy Lane, BS; Carrie Combs, BS; Christian Speas, BS; Delia S. West, PhD; William Herman, MD, MPH

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD; Ann Schwartz, PhD; John Shepherd, PhD; Jason Maeda, MPH; Cynthia Hayashi; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD; Greg Strylewicz, MS

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD; Charles Campbell, AAS, BS; Sharon Hall

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD; Cecilia Farach, DrPH

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Barbara Harrison, MS; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD; Van S. Hubbard, MD PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Eva Obarzanek, PhD, MPH, RD; Denise Simons-Morton, MD, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: David F. Williamson, PhD; Edward W. Gregg, PhD

Acknowledgments

Funding and Support: This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women's Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR-02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center (M01-RR-01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00211-40); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR000056 44) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the University of Washington / VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs. The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: Federal Express; Health Management Resources; Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan Inc.; Optifast-Novartis Nutrition; Roche Pharmaceuticals; Ross Product Division of Abbott Laboratories; and Slim-Fast Foods Company.

APPENDIX A: MODEL DNA CONSENT FORM

Look AHEAD Study – Action for Health in Diabetes Sponsor: National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) MODEL INFORMED CONSENT FORM Based on JAMA 2001;268:1−5. (to be modified to meet local IRB requirements, local center participation in substudies, and local screening visit sequencing)

Principal Investigator___________________________________________________

You have agreed to be part of the Look AHEAD study, the first research study to look at the long-term health effects of weight loss in men and women who are overweight and have diabetes. We are asking all Look AHEAD participants to join a substudy of Look AHEAD that will use genetic materials (DNA) to learn more about body weight and major diseases such as diabetes and heart disease.

The doctor listed above is in charge of this substudy. Other study staff may help or act for this doctor.

Before you can decide whether or not you should agree to join this substudy, you should learn about its risks and benefits. This is called informed consent. Also, please read the attached booklet, Informed Consent: Taking Part in Population-Based Genetic Research. The consent form you are reading describes the substudy that clinic staff will talk to you about. If you decide to join the substudy, you will sign this form. You will be given a copy to keep for your records.

Why is this Study Being Done?

Diabetes, heart disease, and obesity are important health problems that affect many people and have a negative effect on their health and quality of life. Scientists know that genetic factors play a role in these health problems. This substudy will help scientists to learn more about the genetic basis for these conditions and other health problems related to weight and diabetes. It could help them develop better ways to prevent and treat health problems.

What Is Involved In The Study?

If you agree to be part of this substudy, an extra blood sample (about 2 tablespoons) will be taken from your arm and will be treated so that DNA can be taken out and used for research. This sample will be sent for storage at a central laboratory contracted by the coordinating center.

How Will Information About Me Be Kept Private?

Once we take your blood sample, we will assign it a code number. We will separate your name and any other information that points to you from your sample. We will keep files that link your name to the code number in lock filing cabinets at our clinic. Only study staff at your clinic will be allowed to look at these files.

Records that identify you in this study are strictly private. No one other than study staff can ever look at them unless you agree to it. This is because the study has been granted a Certificate of Confidentiality under a federal law (Section 301(d) of the Public Health Service Act). This means that the records of this study may not be disclosed, even under federal, state, or local court order, without your OK. No one who reads or hears about this study will be able to identify your individual information (data) because, before any facts are given out or information is published, we combine your data with those of other people in this study.

What Are The Risks of the Study?

There are no major risks associated with the drawing of blood; however, all medical tests have some risk of injury. Potential risks of drawing blood for the study include the possibilities of brief pain, becoming faint, or developing a bruise or bump following the blood draw. There is a slight risk of infection at the site where blood was drawn.

The kind of information we will look for in this study is not likely to tell you anything specific about your personal health. Even so, there is a risk that if people other than the researchers got your genetic facts they would misuse them. We think the chance of this ever happening to you is very small. To protect your information, we will not keep your name and address with the sample, only a code number. As we said above, files that link your name to the code number will be kept separately in a locked cabinet and only the study staff will be allowed to look at them. Although no one can absolutely guarantee confidentiality, using a code number greatly reduces the chance that someone other than the study staff will ever be able to link your name to your sample or to your test results. Although your name will not be with the sample, it will be linked with other general facts about you such as your race, ethnicity, and sex. These facts are important because they will help us learn if the factors that cause conditions related to heart disease, diabetes, and being overweight to occur or get worse are the same or different in women and men, and in people of different racial or ethnic backgrounds. Thus, it is possible that study findings could one day help people of the same race, ethnicity, or sex as you. However, it is also possible through these kinds of studies that genetic traits might come to be associated with your group. In some cases, this could reinforce harmful stereotypes, but we feel this is unlikely with the types of medical issues that we will be studying.

Are There Any Benefits To Taking Part In This Study?

You will not get any direct benefit for giving a blood sample for this genetics study. By participating in this portion of Look AHEAD, your blood sample may help doctors develop better treatment strategies for diabetes and heart disease, or learn new ways to prevent these diseases in general or in specific subgroups in the population. We also will learn more about the genetics of diabetes and heart disease, which may help doctors provide better medical care, and about conditions that may be improved or perhaps worsened by weight loss.

Are Any Costs or Payments Involved?

It does not cost you anything to provide a blood sample for this study and you will not be charged for any research tests. Participants who participate in the genetic substudy will receive the monetary reimbursement provided to all Look AHEAD participants as described in the study's main consent form, but will not receive additional payment.

In the unlikely event that you are injured while giving a blood sample, we will give you first aid and direct you to proper health treatment. We have not set aside funds to pay for this care or to compensate you if a mishap occurs.

The aim of our research is to improve public health. Your blood will never be used to develop a process or invention that will be sold or patented.

How Will I Find Out About The Results Of The Study?

The studies we do on the samples we collect are to add to our knowledge of how genes and other factors affect health and disease. We are gathering this knowledge by studying groups of people, and the study is not meant to test your personal medical status. For these reasons, we will not give you the results of our research on your sample. However, you can choose to get a newsletter that will tell you about the research studies we are doing. This newsletter will not announce your results or anyone else's, but it will tell you what we are learning about genes and heart disease. We will also publish what we learn in medical journals. If you have questions about whether any genetic tests would be useful to you, you should ask your doctor.

What Will Happen To My Sample After The Study Is Over?

After this study is over, we would like to keep any unused DNA samples left over for future research. These samples will continue to be stored at the contracted central laboratory. We don't have any specific research plans at this time but we would like to use the samples for studies of heart disease, diabetes, and other diseases. We will store the sample under a code number and we will keep the file that links the code number to your name private. We may share the samples with other approved researchers for studies of genes and disease, but we will not give other researchers any information that will allow them to identify you. We will always know which sample belongs to you, but other researchers will not.

An Institutional Review Board, like the one that helps protect you during this research project, will review and approve all future projects.

You can choose not to have your samples stored for future research and still be part of this study. You will have the chance to state your choice about this at the end of this form.

We may create a living tissue sample (called a “cell line”) from which we can get an unlimited supply of genetic material in the future without the need to get more blood from you. Cell lines will be stored at the contracted central laboratory under the same rules as other DNA samples described here.

What Are My Rights as a Participant?

You are free to take part in this study or not. No penalties or loss of benefits will occur if you refuse to take part.

If you decide to take part in this study, you may withdraw at any time. You may choose not to have your sample stored for future research and still be part of this study. Also, may agree to have your DNA stored and later decide that you want to withdraw it from storage. If so, you should call the study person listed in this consent form and tell her to discard your sample. This person will direct the storage facility at the contracted central laboratory to discard your sample, but any data from testing your sample until that point will remain part of the research.

We will give you a copy of this consent form to keep for your records.

Whom Do I Call If I Have Questions or Problems?

If you have any questions about how this study works, contact _____(PC)_____, the chief study person, at ____________________.

If you have any concerns about your rights in the study, contact ___________, head of the Institutional Review Board at ___________.

If you think that being in this study had injured you, contact the ______(PI)____, the chief study person, at ______________ .

Consent And Signature

I agree to give a blood sample for this study. I have been given a chance to ask questions and feel that all of my questions have been answered. I know that giving a sample for this study is my choice. I understand that individual results from this study will not be given to me. I have been given a copy of this consent form to keep.

I have read the part of this form about storing my DNA sample for future research. My choice about having my sample stored and used for future research under the conditions described is (please check ONE box). ___ I refuse to have my blood sample stored for any kind of future research ___ It is OK to store my blood sample with a code number and to use it for any kind of future research related to heart disease, obesity or diabetes that is approved by the Look AHEAD study group. ___ It is OK to store my blood sample with a code number to use future research related to heart disease, obesity or diabetes that is approved by the Look AHEAD study group, but not to create a living tissue sample (cell line)

I would like to receive a newsletter that will tell me about the research study and what researchers are learning in the future studies about genes and disease. Please circle one:

Yes No

Participant ____________________________ Date _______________

I have observed the process of consent. The prospective participant read this form, was given the chance to ask questions, appeared to accept the answers, and signed to enroll in the study.

Witness _______________________________ Date ________________ Signature of the Investigator Investigator ____________________________ Date _________________

Look AHEAD Study Investigators: [include names, addresses, phone numbers] Participant ID: Participant Acrostic:

REFERENCES

- Beskow LM, Burke W, Merz JF, et al. Informed consent for population-based research involving genetics. JAMA. 2001;18:2315–2321. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.18.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli M, Hunter AGW, Stern H, et al. Participation rates of Ashkenazi Jews in a colon cancer community-based screening/prevention study. Clin Genet. 2002;61:104–4. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.610205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton EW, Steinberg KK, Khoury MJ, et al. Informed consent for genetic research on stored tissue samples. JAMA. 1995;274:1786–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr W, Capps L. The challenge of minority recruitment in clinical trials for AIDS. JAMA. 1992;267:954–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel LS, Rothman N, Knott C, et al. Factors associated with refusal to provide a buccal cell sample in the Agricultural Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2002;11:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Lipsitz SR, Molenberghs G, Ibrahim JG. Bias in estimating association parameters for longitudinal binary responses with drop-outs. Biometrics. 2001;57:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froom P, Melamed S, Kristal-Boneh E, Benbassat J, Ribak J. Healthy volunteer effect in industrial workers. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:731–5. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorkin L, Schron EB, Handshaw K, et al. Clinical trial enrollees vs nonenrollers: The Cardiac Arrythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Recruitment and Enrollment Assessment in Clinical Trials (REACT) project. Controlled Clin Trials. 1996;17:46–59. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock CK, Poston WSC, Dill PL, Foreyt JP, Ericsson M. Pharmacotherapy for obesity: a quantitative analysis of four decades of published randomized clinical trials. Int J Obesity. 2002;26:262–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland NT, Smith MT, Eskenazi B, Bastaki M. Biological sample collection and processing for molecular epidemiological studies. Mutation Res. 2003;543:217–34. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(02)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman NA, Andrew LB. Ethical and legal issues in genetic epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1997;19:163–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D, Caporaso N. Informed consent in epidemiologic studies involving genetic markers. Epidemiol. 1997;8:719–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Invited commentary: “Race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:299–304. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Vogler GP, Vandenbergh DJ, Strasser AA, O'Connor RJ, Yost BA. Using a telephone survey to acquire genetic and behavioral data related to cigarette smoking in “Made-Anonymous” and “Registry” samples. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:68–77. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavori PW, Krause-Steinrauf H, Brophy M, et al. Prinicples, organization, and operation of a DNA bank for clinical trials: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Controlled Clin Trials. 2003;23:222–39. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Marchand L, Lum-Jones A, Saltzman B, Visaya V, Nomura AM, Kolonel LN. Feasibility of collecting buccal cell DNA by mail in a cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:701–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, et al. BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer: a prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. JAMA. 1996;275:1885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsted KD, Fraser GE, Steinkohl M, Beeson WL. Healthy volunteer effect in a cohort study: temporal resolution in the Adventist Health Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:783–90. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Look AHEAD Research Group Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes. Design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–28. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato LC, Hill K, Hertert S, Hunninghake DB, Probstfield JL. Recruitment for controlled clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Controlled Clin Trials. 1997;18:328–57. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd Ed. John Wiley; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan GM, Porter KS, Agelli M, Kington R. Consent for genetic research in a general population: the NHANES experience. Genet Med. 2003;5:35–42. doi: 10.1097/00125817-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raich PC, Plomer KD, Coyne CA. Literacy, comprehension, and informed consent in clinical research. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:437–45. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100103137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, Schildkraut JM, Lerman C, Lin TH, Audrain J. Participation in a women's breast cancer risk counseling trial. Who participates? Who declines? High Risk Breast Cancer Consortium. Cancer. 1996;77:2348–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2348::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LW. Informed consent and the capacity for voluntarism. Am J Psychiatr. 2002;159:705–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc . 2004 SAS/STAT 9.1 User's Guide. SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart ML, Jarvis B, Blake B, et al. Recruitment of American Indians in epidemiologic research: the Strong Heart Study. Am Indian Alask Native Ment Health Res. 2000;9:20–37. doi: 10.5820/aian.0903.2000.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M, Shaper AG, Cook DG. Non-participation and mortality in a prospective health study of cardiovascular disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;41:295–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt SB, Diekelmann N, Henderson F, et al. A community-driven model of research participation: the Jackson Heart Study Participant Recruitment and Retention Study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:438–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao LP, Lipsitz S, Lew D. Regression analysis with missing covariate data using estimating equations. Biometrics. 1996;52:1165–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]