Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are ~22-nucleotide endogenous RNAs that often repress the expression of complementary messenger RNAs1. In animals, miRNAs derive from characteristic hairpins in primary transcripts through two sequential RNase III-mediated cleavages; Drosha cleaves near the base of the stem to liberate a ~60-nucleotide pre-miRNA hairpin, then Dicer cleaves near the loop to generate a miRNA:miRNA* duplex2,3. From that duplex, the mature miRNA is incorporated into the silencing complex. Here we identify an alternative pathway for miRNA biogenesis, in which certain debranched introns mimic the structural features of pre-miRNAs to enter the miRNA-processing pathway without Drosha-mediated cleavage. We call these pre-miRNAs/introns ‘mirtrons’, and have identified 14 mirtrons in Drosophila melanogaster and another four in Caenorhabditis elegans (including the reclassification of mir-62). Some of these have been selectively maintained during evolution with patterns of sequence conservation suggesting important regulatory functions in the animal. The abundance of introns comparable in size to pre-miRNAs appears to have created a context favourable for the emergence of mirtrons in flies and nematodes. This suggests that other lineages with many similarly sized introns probably also have mirtrons, and that the mirtron pathway could have provided an early avenue for the emergence of miRNAs before the advent of Drosha.

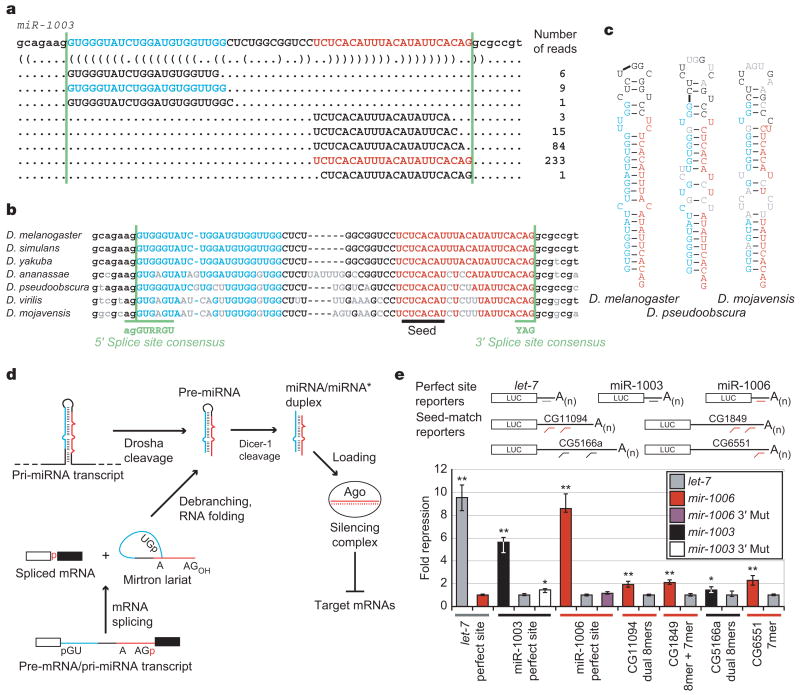

While examining sequencing data of small RNAs from D. melanogaster4, we observed clusters of small RNAs originating from the outer edges of an annotated 56-nucleotide (56-nt) intron (Fig. 1a). These sets of reads (each read representing an independently sequenced complementary DNA) had properties similar to those observed previously for miRNA:miRNA* duplexes5, in that each set had a more consistent 5′ than 3′ terminus, and the two sets were complementary to each other, with the dominantly abundant species of each set forming 2-nt 3′ overhangs when paired to each other. Moreover, the sequence and predicted secondary structure of the intron were conserved in a pattern resembling that of pre-miRNAs6 (Fig. 1b, c). We annotated this locus as mir-1003.

Figure 1. Introns that form pre-miRNAs.

a, D. melanogaster mir-1003 with corresponding reads from high-throughput sequencing4. The miRNA (red), miRNA* (blue) and splice sites (green lines) are indicated, with predicted secondary structure shown in bracket notation26. b, Conservation of mir-1003 across seven Drosophila species22,25, coloured as in a, and also indicating consensus splice sites12 (green) and nucleotides differing from D. melanogaster (grey). c, Predicted secondary structures of representative debranched pre-miR-1003 orthologues, coloured as in b. d, Model for convergence of the canonical and mirtronic miRNA biogenesis pathways (see text). e, MicroRNA regulation of luciferase reporters in S2 cells. Plotted is the ratio of repression for wild-type versus mutated sites, normalized to that with the indicated non-cognate miRNA. Bar colour represents the cotransfected miRNA expression plasmid; coloured lines below indicate the cognate miRNA for the specified reporter. Error bars represent the third largest and smallest values from 12 replicates (four independent experiments, each with three transfections; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001, Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

Despite these clearly miRNA-like properties, semblance to canonical miRNA primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) stopped abruptly at the borders of the intron. Pairing at the base of the hairpin did not extend beyond the miRNA:miRNA* duplex—that is, beyond the splice sites. In place of extended pairing, which is needed for pri-miRNA cleavage by Drosha (ref. 7), the intron had conserved canonical splice sites (Fig. 1b), leading to the model that this miRNA did not arise from a canonical miRNA biogenesis pathway but instead arose from an alternative pathway in which splicing, rather than Drosha, defined the pre-miRNA (Fig. 1d). Consistent with this model, spliced lariats linearized by the lariat debranching enzyme bear 5′ monophosphates8 and 3′ hydroxyls9, the same moieties found in pre-miRNAs1,3,10.

Thirteen additional pre-miRNAs/introns, termed mirtrons, were found in a search of other loci with similar properties (mir-1004–1016, Supplementary Table S1). The most abundant RNA species from each of the 14 mirtrons, annotated as the mature miRNA, derived from the 3′ arm of its hairpin. Such bias was consistent with the known 5′ nucleotide biases of miRNAs, which frequently begin with a U and rarely with a G (ref. 11). The near-ubiquitous intronic 5′ G, together with other requirements at intron 5′ ends12, would place unfavourable constraints on miRNAs deriving from the 5′ arm of a mirtron, whereas the species from the 3′ arm would have more freedom. As expected, the species from the 3′ arms, like canonical miRNAs, usually had a 5′ U (12/14 mirtrons).

To test whether the small RNAs from mirtrons were functional miRNAs or inactive degradation intermediates, we assessed the gene-silencing capacities of miR-1003 and miR-1006 in Drosophila S2 cells. In animals, extensive complementarity leads to cleavage of the target mRNA, but post-transcriptional repression is more commonly mediated by less extensive complementarity, primarily involving pairing to a 5′ region of the miRNA known as the miRNA seed1. miR-1003 and miR-1006 repressed reporter genes with perfectly complementary sites, with the repression levels approaching that observed for the let-7 miRNA and an analogous reporter (Fig. 1e). In addition, both mirtronic miRNAs repressed reporter genes containing Drosophila untranslated region (UTR) fragments with seed-based matches typical of metazoan miRNA targets. Conservation of the miR-1003 and miR-1006 seeds (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Table S1) suggested an in vivo role for such mirtron-mediated repression; target predictions for conserved mirtronic miRNAs are provided (http://www.targetscan.org).

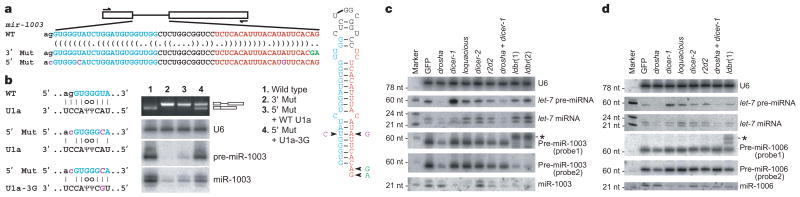

Having established that mirtrons can direct miRNA-like gene repression, we tested the dependence of mirtron processing on splicing and debranching. A mutant mir-1003 with a substitution that impaired splicing (3′ Mut) generated little pre- or mature miR-1003 (Fig. 2a, b) and displayed significantly less silencing activity (Fig. 1e). Mutations disrupting the 5′ splice site (5′ Mut) also impaired splicing and miR-1003 accumulation (Fig. 2a, b). Coexpressing a mutant U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA; U1-3G) that had compensatory changes designed to restore splice site recognition13 restored splicing of mir-1003 5′ Mut (Fig. 2b). Rescuing splicing also restored the levels of pre- and mature miR-1003 (Fig. 2b). These results demonstrated that splicing was required for mirtron maturation and function, which contrasts with the splicing-independent biogenesis of canonical miRNAs found within introns14.

Figure 2. Mirtrons are spliced as introns and diced as pre-miRNAs.

a, Schematic of splice-site mutations. b, Base pairing between the indicated U1a and mir-1003 RNAs (left), and RT–PCR and northern-blot analyses of mir-1003 variants from a. The miR-1003 bands in lane 2 were attributed to endogenous miRNA. c, Northern blots analysing let-7 and mir-1003 maturation in cells treated with double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) corresponding to indicated genes. Shown are results from one membrane, sequentially stripped and probed for let-7 RNA, pre-miR-1003/lariat (probe 1), pre-miR-1003/miR-1003 (probe 2), and U6. Previously validated dsRNAs were used28,29, except for lariat debranching enzyme (CG7942, which we name ldbr), for which two unique dsRNAs were used. Knockdowns were confirmed by monitoring mRNA level and protein function (Supplementary Fig. S2). Quantification of band intensities is provided (Supplementary Table S3). *Lariat. d, Analysis of mir-1006 processing, as in c.

We next used RNA interference (RNAi) knockdown experiments to examine the trans-factor requirements for miR-1003 and miR-1006 biogenesis in Drosophila cells. As predicted by our model, in which mirtrons enter the miRNA biogenesis pathway after splicing and debranching, targeting the mRNA of lariat debranching enzyme reduced the amount of pre- and mature mirtronic miRNAs without impeding canonical miRNA maturation (Fig. 2c, d). For each mirtron, a probe to the 5′ end of the intron (probe 1) detected both the pre-miRNA hairpin and the accumulating lariat, whereas a probe to the 3′ end of the intron (probe 2) detected the pre-miRNA but failed to detect the lariat, presumably owing to overlap with the branch-point (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Altered relative mobility on gels with different polyacrylamide densities confirmed detection of the mirtron lariat (Supplementary Fig. S1b). The debranching knockdown results, together with those of the splice-site mutations and rescue, demonstrated that the intron lariat was an intermediate on the pathway of mirtronic miRNA biogenesis.

Knockdown of other miRNA biogenesis factors further supported our model. As expected if debranched mirtrons enter the later steps of the miRNA pathway rather than the short interfering RNA (siRNA) pathway3, knockdown of dicer-1 or its partner, loquacious, increased the ratio of pre- to mature mirtronic miRNA, whereas knockdown of dicer-2 or its partner, r2d2, did not (Fig. 2c, d). Knockdown of drosha decreased pre- and mature let-7 RNA accumulation, with little effect on mature miR-1003 or miR-1006 accumulation and a modest effect on mirtronic pre-miRNAs (Fig. 2c, d). The more modest effect on mirtronic pre- and mature miRNAs supported the idea that mirtronic pre-miRNAs are not Drosha cleavage products. The decrease of mirtronic pre-miRNA that was observed would be explained if Drosha bound mirtron ic pre-miRNAs, stabilized them from degradation, and perhaps facilitated their loading into the nuclear export machinery. The decrease could also reflect increased Dicer-1 accessibility in the drosha knockdown due to reduced substrate competition from endogenous pre-miRNAs. In this case, simultaneous knockdown of dicer-1 and drosha would lead to a more substantial accumulation of pre-miRNAs derived from mirtrons than from canonical miRNAs, as was observed for pre-miR-1003 and pre-miR-1006 compared to let-7 pre-miRNA (Fig. 2c, d).

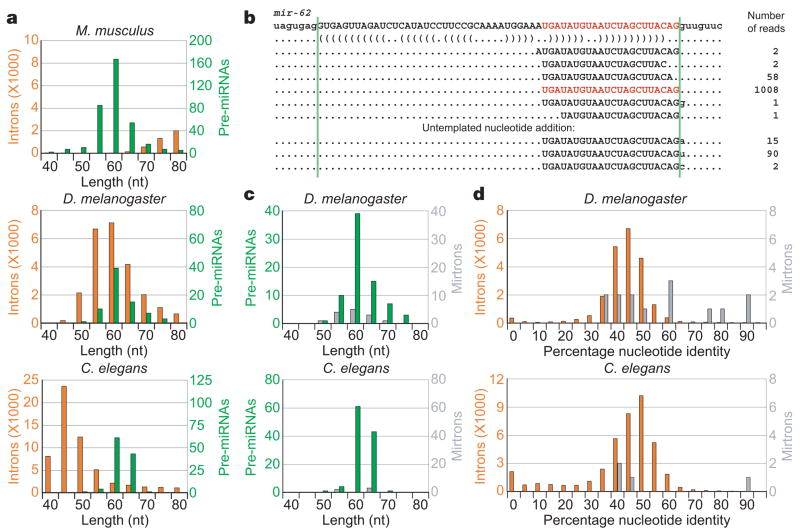

The distribution of intron lengths, which varies widely in different organims12,15, would influence the probability of new mirtrons arising during evolution. The introns of Drosophila share a similar length distribution with the annotated pre-miRNAs, producing a context particularly well suited to the emergence to mirtrons (Fig. 3a, c). C. elegans also has a substantial number of pre-miRNA-sized introns. Indeed, examination of prior miRNA annotations revealed that mir-62, which produces a highly conserved nematode miRNA that was among the very first to be cloned in animals11,16, had mirtron-like properties (Fig. 3b). Like the mirtrons of D. melanogaster, the base pairing capacity of the sequence surrounding pre-miR-62 ended at the border of the host intron, and the most abundant miRNA 3′ terminus corresponded to the 3′ splice site (with the single read whose 3′ terminus extended into the 3′ exon attributable to untemplated nucleotide addition to the miRNA 3′ end5). A directed search of C. elegans small RNA sequences5 revealed three more mirtrons, annotated here as mir-1018–1020 (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3. Emergence and conservation of mirtrons in species with appropriately sized introns.

a, Distributions of intron (orange) and pre-miRNA (green) lengths from the indicated species. Introns and pre-miRNAs were binned by length. b, Intron and associated reads of C. elegans mir-62 (ref. 5), coloured as in Fig. 1a. Reads with untemplated nucleotides added at their 3′ terminus are shown below. c, Distributions of pre-miRNA (green) and mirtron (grey) lengths from D. melanogaster and C. elegans. d, Conservation of all 40–90-nt introns (orange) versus mirtrons (grey) from D. melanogaster (percentage identity shared with D. pseudoobscura) and C. elegans (percentage identity shared with C. briggsae).

Even if only a very small portion of debranched introns can form secondary structures resembling those of pre-miRNAs, the abundance of pre-miRNA-sized introns in flies and nematodes would allow a large absolute number of candidate mirtrons to emerge over evolutionary timescales. Whether they persist as functional mirtrons depends on the selective advantage conferred to the host organism as a consequence of their gene-repression activities. This model for mirtron emergence predicts that, at any historical point, some introns will be processed as mirtrons that provide no advantage to the organism but have yet to be eliminated by natural selection or neutral drift. Accordingly, some but not all processed D. melanogaster mirtrons were significantly more conserved in Drosophila pseudoobscura than were most small introns, and the same trend was observed for C. elegans mirtrons in Caenorhabditis briggsae (Fig. 3d). The three most conserved D. melanogaster mirtrons (mir-1003/1006/1010) gave rise to more reads than 27%, 16% and 4% of the non-mirtronic miRNAs conserved to D. pseudoobscura, respectively4, while the most conserved C. elegans mirtron (mir-62) gave rise to more reads than 52% of the non-mirtronic miRNAs conserved to C. briggsae5.

Compared to flies and nematodes, mammals have few pre-miRNA-sized introns12,15 (Fig. 3a), perhaps explaining why we found no mirtrons among the annotated mammalian miRNAs17. Nonetheless, high-throughput sequencing of mammalian small RNAs might yet reveal mirtrons. In plants, miRNA processing could similarly bypass one of the RNase III cleavages, although plant mirtrons have not yet been identified1,17. Moreover, lineages with long introns might have other types of intronic miRNAs that bypass Drosha-mediated cleavage. This possibility was raised by mir-1017, whose putative pre-miRNA 5′ end, but not 3′ end, matched the 5′ splice site of its host intron (Supplementary Table S1). In contrast to true mirtrons, miRNAs of this type would depend on a nuclease to cleave their extensive 3′ overhangs, as observed for the U14 snRNA derived from an intron of hsc70 (ref. 18). This mechanism, together with that of mirtron processing, would enable miRNAs to emerge in any organism with both splicing and post-transcriptional RNA silencing, even those lacking the specialized RNase III enzyme Drosha or its plant counterpart, DICER-LIKE1 (ref. 1). In this scenario, miRNAs might have emerged in ancient eukaryotes before the advent of modern miRNA biogenesis pathways.

METHODS SUMMARY

Computational methods

D. melanogaster small RNAs were from 2,075,098 high-throughput pyrosequencing reads4 and are available at the GEO. C. elegans small RNA sequences were from ref. 5. Introns were as annotated in FlyBase (v4.2)19, WormBase (release WS120)20 and human RefSeq annotations21 available through UCSC (hg17)22. Percentage conservation of D. melanogaster23 and D. pseudoobscura24 introns was calculated as the number of identity matches between the two orthologous introns in the multiZ alignment22,25 divided by the length of the longer intron. C. elegans intron conservation was similarly determined using multiZ alignments22 of the C. elegans and C. briggsae (WormBase cb25.agp8) genomes20,22. Pre-miRNA lengths were the sum of the miRNA length, the miRNA* length, and the length of intervening sequence, calculated after using RNAfold26 to predict the structure of annotated miRNA hairpins (miRBase v9.1)17 and inferring the miRNA* by assuming 2-nt 3′ overhangs when paired with the annotated miRNA.

Analysis of function and biogenesis

Mirtron minigenes containing flanking exons were amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into expression vectors, pMT-puro or p2032 (ref. 27). Similar plasmids were constructed for a 780-base-pair (780-bp) fragment centred on the let-7 hairpin. Luciferase reporters were constructed with 3′ UTRs (Supplementary Table S3) amplified from genomic DNA. U1 plasmids were constructed as described13. Mutations to seed sites (reporters) or splice sites (minigenes) were introduced by Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene). After RNAi knockdown28,29, miRNA expression was induced with 500 μM CuSO4, then 12 h post-induction RNA was extracted with TRI reagent and analysed on northern blots5. Renilla (reporter) and firefly (control) luciferase plasmids were cotransfected with miRNA-expressing plasmid into S2 cells. Fold repression was calculated by dividing normalized luciferase activity for mutant reporters by that of wild-type reporters in the presence of cognate miRNA. Transfection with non-cognate miRNA served as a specificity control.

METHODS

Computational methods

D. melanogaster small RNAs were from 2,075,098 high-throughput pyrosequencing reads4 and are available at the GEO. C. elegans small RNA sequences were from ref. 5. Introns were defined according to FlyBase v4.2 D. melanogaster gene annotations19. C. elegans introns were defined using annotations and genomic sequence from WormBase (release WS120)20. Mus musculus introns were defined using NCBI RefSeq annotations21 applied to the March 2005 release of the mouse genome available through UCSC (mm6)22. RNA secondary structures were predicted using RNAfold26. D. melanogaster intron conservation was assessed based on a nine-species multiZ alignment25 of D. melanogaster, Drosophila simulans, Drosophila yakuba, Drosophila ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, Drosophila virilis, Drosophila mojavensis, Anopheles gambiae and Apis mellifera genomes, generated at UCSC22. Percentage nucleotide identity between D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura introns was calculated as the number of identity matches between the two orthologous introns in the multiZ alignment divided by the length of the longer intron. Introns not aligned between those two species were not tallied. C. elegans intron conservation was similarly determined using multiZ alignment of the C. elegans and C. briggsae (WormBase cb25.agp8)20 genomes generated at UCSC22. Pre-miRNA lengths were calculated using miRBase v9.1 hairpin annotations17. Secondary structures were generated using RNAfold26, and the miRNA* position was inferred on the basis of the annotated miRNA, assuming 2-nt 3′ overhangs. Pre-miRNA lengths were the sum of the miRNA length, the miRNA* length, and the length of intervening sequence.

Plasmids

Minigenes containing mir-1003 and mir-1006 and flanking exons were PCR amplified from genomic DNA. Minigenes for mir-1006 and mir-1003 were cloned into pMT-puro with the indicated sites to make expression plasmids pCJ19 and pCJ20, respectively. let-7 was amplified from genomic DNA with primers 474 bp upstream and 310 bp downstream of the let-7 hairpin and cloned into pMT-puro to make pCJ24. Similar minigenes replaced EGFP in p2032 (ref. 27) to give pCJ31 (mir-1006), pCJ30 (mir-1003) or pCJ32 (let-7). U1a snRNA and U1a-3G snRNA expression constructs were constructed essentially as described13. Sequences of inserts in pCJ19 (pMT-puro-mir-1006), pCJ20 (pMT-puro-mir-1003), pCJ24 (pMT-puro-let-7), pCJ30 (p2032-mir-1003), pCJ31 (p2032-mir-1006), and pCJ32 (p2032-let-7) are provided (Supplementary Table S4). Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) was used to make 3′ splice site mutations with the indicated primers: mir-1003 3′ mut (CCTCTCACATTTACATATTCACGACGCCGTGAGCTGC and GCAGCTCACGGCGTCGTGAATATGTAAATGTGAGAGG), and mir-1006 3′ mut (GGTACAATTTAAATTCGATTTCTTATTCATGCGTGCAATACCAGTTGATC and GATCAACTGGTATTGCACGCATGAATAAGAAATCGAATTTAAATTGTACC). Similarly, mir-1003 5′ mut was made with the following mutagenic primers: (GCTGCGCAGAACGTGGGCATCTGGATGTGGTTGGC and GCCAACCACATCCAGATGCCCACGTTCTGCGCAGC; CCTCTCACATTTACATGTTCACAGGCGCCGTGAG and CTCACGGCGCCTGTGAACATGTAAATGTGAGAGG).

Luciferase-reporter inserts were made by annealing oligonucleotides with their reverse complements, leaving overhangs for the indicated restriction sites (lower case): let-7-ps (gagctcACTATACAACCTACTACCTCAactagt), let-7-psm (gagctcACTATACAACCTACAAGCACAactagt), miR-1003-ps (gagctcCTGTGAATATGTAAATGTGAGAactagt), miR-1003-psm (gagctcCTGTGAATATGTAAAAGAGTGAactagt), miR-1006-ps (gagctcCTATGAATAAGAAATCGAATTTAactagt), and miR-1006-psm (gagctcCTATGAATAAGAAATCCATTATAactagt). Annealed oligos were ligated into SacI/SpeI-cleaved pIS2 (ref. 30). These plasmids were linearized with HindIII, polished with Klenow enzyme to create blunt ends, and digested with NotI to excise the Renilla luciferase gene with the modified UTR from the remainder of pIS2. The gel-purified Renilla gene fragment was then ligated into pMT-puro between EcoRV and NotI sites for copper-induced expression in S2 cells.

Cell culture and RNAi

S2-SFM cells were adapted from S2 cells to grow in Drosophila serum free media (SFM) by passaging into increasing amounts of SFM (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 100%), then grown in SFM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine at 25 °C in a humidified incubator. 5 μg of pCJ19 or pCJ20 were transfected into a 60 mm plate containing 2.5 × 106 S2 cells with FuGENE HD. Cells were grown for 3 days, split 1:10, and selected for 3 weeks in 10 μg ml−1 puromycin before experimentation, then maintained in 5 μg ml−1 puromycin.

Templates for dsRNA were amplified by PCR and extended to have convergent T7 promoters. 400 μl PCR reactions were phenol/chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and used as template for 400 μl T7 transcriptions. Transcription reactions were treated with 20 U of DNase I for 15 min. The transcription products were then extracted in phenol:chloroform (5:1 pH 5.3) and ethanol precipitated. RNA was resuspended, desalted over Sephadex G-300, then heated to 75 °C for 10 min and slow cooled to room temperature. Yield and quality were assessed by agarose gel and UV absorbance. The sense sequence of each dsRNA is listed (Supplementary Table S4).

S2 cells were soaked in 10 μg ml−1 dsRNA in SFM. 500,000 cells were plated per well of a 24-well plate and soaked for 2 days, split 1:4, soaked another 2 days, expanded into 6-well plates, then soaked for three days. MicroRNA expression was induced by addition of 500 μM CuSO4 to the growth media, and RNA harvested 12 h later with TRI reagent.

Northern blots were performed as described5, using the following oligonucleotides (purchased from IDT) as probes for the indicated RNA species (‘+’ precedes LNA bases): ACTATACAACCTACTACCTCA (let-7), C+TGT+GAA+TAT+GTA+AAT+GTG+AGA (mir-1003 probe 1), CCAACCACATCCAGATACCCACC (mir-1003 probe 2), C+TAT+GAA+TAA+GAA+ATC+GAA+TTT+A (mir-1006 probe 1), TTTACGCATTTCAATTTCAAACTCAC (mir-1006 probe 2), TTGCGTGTCATCCTTGCGCAGG (U6).

RT–PCR

500 ng mirtron plasmids were cotransfected with 500 ng either U1 or GFP carrier plasmid using 3 μl FuGENE HD per well of a 12 well plate. 24 h post-transfection, mirtron expression was induced for 36 h in the presence of 500 μM CuSO4. Total RNA was extracted with TRI reagent, and 4 μg were treated with DNase using the DNA-free kit (Ambion). 500 ng DNA-free RNA were reverse-transcribed with oligo-dT(16) and Superscript III (Invitrogen) per manufacturers instructions. 1 μl cDNA was used as a template for PCR using exonic primers (ATAAAGCCGATAAGCGTGCG and CGTCCTTGTGCGTCTCCTCC) flanking mir-1003. After 24 cycles of PCR, 10 μl of the reaction was resolved on an ethidium-stained 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by UV illumination.

Quantitative RT–PCR was performed on an ABI 7000 Real-Time PCR system with ABI Power SYBR Green reagents. First-strand synthesis was performed as above. The following primer pairs were used to amplify the specified mRNA: actin 5c (CCCATCTACGAGGGTTATGC, TTGATGTCACGGACGATTTC); drosha (TCACCATCCACGAGCTAGAC, ACGAAACGCGGAAAGAAGTG); dicer-1 (GCCATTGAAGCATGACATTG, AAATCCCTCCTTGCCGATAG); loquacious (CGATTACCGAGTGGATACGG, CAAAGGAATCGGTGGAAAAG); dicer-2 (GGCCACGAAACTTAAAGAGC, TGTGGAAAGGACACCATGAC); r2d2 (GACGGAGGGTACGTCTGTAAA, AGCAGTTGGATTTTACGCAAG); ldbr (TTATCCCTGCCAGCACCTAC, CCTCTACATGAGGCGTTTCC).

Threshold cycle (Ct) and baseline were detected by ABI 7000 SDS software. actin 5C was used to calculate the ΔCt, and ΔΔCt was calculated by subtracting the ΔCt from that of the GFP dsRNA treated samples; the relative abundance was calculated as 1/(2ΔΔCt). Geometric mean ± standard deviation are shown for three replicate wells.

Luciferase assays

S2-SFM cells were plated 300,000 cells ml−1 in 96 well plates. After 24 h, cells were cotransfected with 96 ng microRNA-expressing plasmid, 4 ng perfect-site reporter and 2 ng firefly reporter per well using FuGENE HD (3 μl lipid per μg DNA). Expression of Renilla luciferase was induced 24 h post-transfection with 500 μM CuSO4. Luciferase assays were performed 24 h post-induction with the Dual-Glo Luciferase system (Promega) on a Tecan Safire2 plate reader. The ratio of Renilla:firefly luciferase activity was measured for each well. To calculate fold repression, the ratio of Renilla:firefly for reporters with mutant sites was divided by the ratio of Renilla:firefly for reporters with wild-type sites. These values were also obtained in the presence of a plasmid expressing a non-cognate miRNA, and fold repression for the cognate miRNA was normalized to that of the non-cognate.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to P. Sharp, T. Baker and members of the Bartel laboratory for discussions. We thank W. Johnston for assistance with molecular cloning, E. Lai for contributing small-RNA-derived cDNAs for sequencing, the Drosophila genome sequencing community and the UCSC genome browser staff for unpublished alignments, P. Zamore and R. Green for dsRNA plasmids, S. Cohen for GFP and firefly luciferase Drosophila expression plasmids, and D. Sabitini for pMT-puro. This work was supported by the NIH. C.H.J. is a NSF graduate research fellow. D.P.B. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee Y, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Perspective: machines for RNAi. Genes Dev. 2005;19:517–529. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruby JG, et al. Biogenesis, expression, and target predictions for an expanded set of microRNA genes in Drosophila. Genome Res. doi: 10.1101/gr.6597907. in the press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruby JG, et al. Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;127:1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim LP, et al. The microRNAs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 2003;17:991–1008. doi: 10.1101/gad.1074403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han J, et al. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex. Cell. 2006;125:887–901. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruskin B, Green MR. An RNA processing activity that debranches RNA lariats. Science. 1985;229:135–140. doi: 10.1126/science.2990042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padgett RA, Konarska MM, Grabowski PJ, Hardy SF, Sharp PA. Lariat RNA’s as intermediates and products in the splicing of messenger RNA precursors. Science. 1984;225:898–903. doi: 10.1126/science.6206566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutvagner G, et al. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim LP, Burge CB. A computational analysis of sequence features involved in recognition of short introns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11193–11198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201407298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo PC, Roy D, Mount SM. Suppressor U1 snRNAs in Drosophila. Genetics. 1994;138:365–378. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YK, Kim VN. Processing of intronic microRNAs. EMBO J. 2007;26:775–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yandell M, et al. Large-scale trends in the evolution of gene structures within 11 animal genomes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D109–D111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leverette RD, Andrews MT, Maxwell ES. Mouse U14 snRNA is a processed intron of the cognate hsc70 heat shock pre-messenger RNA. Cell. 1992;71:1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grumbling G, Strelets V. FlyBase: anatomical data, images and queries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D484–D488. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein L, Sternberg P, Durbin R, Thierry-Mieg J, Spieth J. WormBase: network access to the genome and biology of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:82–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruitt KD, Tatusova T, Maglott DR. NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq): a curated non-redundant sequence database of genomes, transcripts and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D501–D504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karolchik D, et al. The UCSC genome browser database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:51–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams MD, et al. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000;287:2185–2195. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards S, et al. Comparative genome sequencing of Drosophila pseudoobscura: chromosomal, gene, and cis-element evolution. Genome Res. 2005;15:1–18. doi: 10.1101/gr.3059305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchette M, et al. Aligning multiple genomic sequences with the threaded blockset aligner. Genome Res. 2004;14:708–715. doi: 10.1101/gr.1933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofacker IL, et al. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Mh Chem. 1994;125:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorner S, et al. A genomewide screen for components of the RNAi pathway in Drosophila cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11880–11885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605210103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forstemann K, et al. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lim LP, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.