Abstract

Functional contributions of residues Val-99—Ser-126 lining extracellular loop (EL) 1 of the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter were determined via cysteine-scanning mutagenesis, thiol modification, and in silico interpretation. Despite membrane expression for all but three constructs (S112C, Y117C, S126C), most EL1 mutants (64%) were inactivated by cysteine mutation, suggesting a functional role during sodium/bile acid co-transport. A negative charge at conserved residues Asp-120 and Asp-122 is required for transport function, whereas neutralization of charge at Asp-124 yields a functionally active transporter. D124A exerts low affinity for common bile acids except deoxycholic acid, which uniquely lacks a 7α-hydroxyl (OH) group. Overall, we conclude that (i) Asp-122 functions as a Na+ sensor, binding one of two co-transported Na+ ions, (ii) Asp-124 interacts with 7α-OH groups of bile acids, and (iii) apolar EL1 residues map to hydrophobic ligand pharmacophore features. Based on these data, we propose a comprehensive mechanistic model involving dynamic salt bridge pairs and hydrogen bonding involving multiple residues to describe sodium-dependent bile acid transporter-mediated bile acid and cation translocation.

Bile acids are synthesized de novo in the liver via FXR- and CYP7A-mediated processes from their precursor cholesterol, secreted into bile, stored in the gallbladder, and released into the intestine in response to food intake (1). The relatively small (38–41 kDa), high capacity transporter ASBT3 (apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter; SLC10A2) accounts for the majority of active intestinal bile acid recapture (1). Once internalized, reclaimed bile acids are secreted into portal circulation via OSTα-OSTβ for return to the liver via the hepatic bile acid transporter, NTCP (1–3), thereby completing one cycle of enterohepatic circulation (4). Clinically, the intimate link between ASBT and cholesterol may be exploited via blockage of bile acid reuptake, resulting in reduced cholesterol levels (5–9); this establishes the pharmaceutical relevance of ASBT in treatment of hypercholesterolemia (1, 10–14). Moreover, ASBT constitutes an attractive target for prodrug strategies aimed at increasing oral bioavailability of poorly absorbed drugs (15–17). Despite important clinical applications, the molecular mechanisms underlying ASBT transport are poorly understood.

In an effort to elucidate critical components of the transport cycle, particularly protein segments or amino acids involved in substrate recognition, binding, and permeation, our present study applies the validated cysteine-scanning accessibility mutagenesis technique (18–20). Using this approach, we have thus far identified putative portions of the substrate permeation path, including specific protein regions likely interacting or binding substrates of ASBT (21–24). Here, we focused on the highly conserved, large extracellular loop 1 (EL1) spanning 27 amino acids (Val-99—Ser-126) based on the following rationale. (i) The functional importance of charged protein residues during Na+ and bile acid binding events, as demonstrated by our group (21, 25) and others (26), suggests functional involvement of Asp-120, Asp-122, and Asp-124, which are clustered along the distal half of EL1 during Na+ binding events. Moreover, numerous polar residues, also capable of long range electrostatic interactions with charged substrates, are present throughout the EL1 segment. Prior studies using ASBT orthologs (26) and paralogs (27) concluded that the EL1-localized Asp-122 (Asp-115 in NTCP) may form a sodium sensor, binding one of the two co-transported Na+ ions during the ASBT transport cycle. (ii) Both EL1 and EL3 protein segments have been speculated to act as re-entrant loop segments by Zahner et al. (27), who postulated the formation of a P-loop structure by EL1/3 to explain transport mechanisms of the rat Ntcp and recently purported for ASBT (16). Although such a mechanism remains experimentally unverified, it nonetheless spotlights the need for a systematic analysis of this loop segment to increasing our overall understanding of ASBT transport mechanisms and, indeed, solute transporters in general. Toward this aim we have incorporated individual cysteine substitutions along EL1 against our previously established parental scaffold, C270A, followed by thiol modification and structural and functional assessments of each mutant transporter. Our results demonstrate putative sodium and bile acid interactions along EL1; furthermore, long-range electrostatic and dipole-dipole interactions between essential EL1 and EL3 residues may contribute to proper tertiary structure of substrate binding cavities and couple cooperative binding events. We conclude a functional contribution of a string of conserved aspartic acids lining EL1, with Asp-120 and/or Asp-122 functioning as a putative sodium sensor and Asp-124 mediating protein contacts with the cholestane skeleton of bile acids. Additionally, a mechanism coupling binding of two sodium ions at their respective binding sites, Asp-122 and the previously identified Glu-261, (21) is posited based on integration of our results.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—[3H]Taurocholic acid (0.2 Ci/mmol) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. (St. Louis, MO); taurocholic acid (TCA), cholic acid, deoxycholic acid (DCA), chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), taurochenodeoxycholic acid (TCDCA), and glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA) from Sigma; (sulfosuccinimidyl-2 (biotinamido) ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate (sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin) from Pierce; and [2-(trimethylammonium) ethyl] methanethiosulfonate (MTSET) and 2-((biotinoyl)amino)ethyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSEA biotin) from Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc. (North York, ON, Canada). Cell culture media and supplies were obtained from Invitrogen. All other reagents and chemicals were of highest purity available commercially.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfections—COS-1 cells (ATCC CRL-1650) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal calf serum, 4.5 g/liter glucose, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Transient transfections were performed as previously described (22).

Site-directed Mutagenesis—Site-directed mutations were incorporated into hASBT cDNA using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA), and mutagenesis primers were custom-synthesized and purchased from Sigma Genosys. Plasmid purifications were performed using a kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA), and amino acid substitutions were confirmed via DNA sequencing using an ABI 3700 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the Plant-Microbe Genomics Facility of The Ohio State University.

Bile Acid Uptake Assay—Initial rates of transport for each mutant were determined in transiently transfected COS-1 cells incubated in modified Hanks' balanced salt solution (MHBSS), pH 7.4, uptake buffer containing 5.0 μm [3H]TCA at 37 °C for 12 min. This uptake period ensures linear steady-state kinetics in conjunction with an optimal signal-to-noise ratio for subsequent [3H]TCA analysis via liquid scintillation counting (22, 23, 28). Uptake was halted by a series of washes with ice-cold Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.2% fatty acid free bovine serum albumin and 0.5 mm TCA. Cells were lysed in 350 μl of a 1 n NaOH, and aliquots were analyzed using an LS6500 liquid scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA) and total protein quantification using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Uptake activity was calculated as pmol of [3H]TCA internalized/min/mg of protein.

For inhibition studies, uptake of 5 μm [3H]TCA was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of each bile acid analog (10–8–10–2 m). Uptake rates were plotted against inhibitor concentration. Kinetic data were analyzed using nonlinear least-squares fitting by SigmaPlot software (Jandel Scientific). For bile acid uptake kinetics, constants were derived by fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation, V = Vmax[S]/(Km + [S]), where [S] is bile acid concentration, Vmax is uptake rate at saturating [S], and Km is the substrate concentration at 0.5 Vmax. IC50 values were calculated using competitive inhibition kinetics, E = Emax(1 – [S]/([S] + IC50), where Emax is uptake of [3H]TCA in the absence of inhibitor, and [S] is inhibitor concentration.

Protein Membrane Expression—Protein expression was determined as described previously (23). Briefly, transiently transfected COS-1 cells were lysed, separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred onto an immunoblot polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). Blots were probed with rabbit anti-ASBT primary antibody (1:1000) and visualized using goat anti-rabbit IgG/horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:30,000) with chemiluminescent detection (ECL Plus Western blot kit, Amersham Biosciences). Levels of cell surface protein expression were measured via biotin labeling of transiently transfected COS-1 cells with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin for 30 min at room temperature (29, 30). After several washes with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mm CaCl2, MgCl2, and 100 mm glycine, cells were disrupted with 0.4 ml of lysis buffer B at 4 °C for 20 min (25), and biotinylated proteins were recovered overnight at 4 °C using 100 μl of streptavidin-agarose beads. Samples were eluted with SDS-PAGE buffer, and immunoblotting was performed as described above. Blots were probed for positive and negative controls, the plasma membrane marker α-integrin (150 kDa), and the endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein calnexin (90 kDa) to assess the integrity of the biotinylation procedure (calnexin data not shown). Relative ASBT membrane expression was standardized to integrin expression and quantified via densitometry as previously described (23).

Sodium Activation and Kinetics—Measurement of [3H]TCA uptake at equilibrating extracellular Na+ concentrations (12 mm, i.e. at equilibrium with cytosolic [Na+]) was performed (uptake conducted as described above; choline chloride used as equimolar NaCl replacement) and expressed as a ratio of uptake at physiological (137 mm) Na+ concentrations to determine overall sensitivity of each mutant to the presence/absence of Na+. Theoretically, Na+ ratios equal to one imply little measurable difference in transporter activity despite the scarcity of Na+ ions, whereas fractions less than one indicate a greater necessity for physiological Na+ concentrations for proper transport function of a mutant transporter.

For sodium activation kinetics, uptake of 5 μm [3H]TCA was measured at sodium concentrations ranging from 0 to 137 mm with isomolarity maintained with choline chloride. Kinetic constants were derived by fitting data to the Hill equation, V = Vmax[Na+]n/(KNan[Na+]n), where [Na+] is sodium concentration, Vmax is uptake rate at saturating [Na+], i.e. 137 mm, KNa is the sodium concentration at 0.5 Vmax, and n is the Hill coefficient.

MTS Inhibition Studies—Sensitivity of mutants to the positively charged, membrane-impermeant MTSET (1 mm) was determined by preincubation of transiently transfected COS-1 cells for 10 min at room temperature followed by 2 washes with MHBSS, pH 7.4, and [3H]TCA uptake as described above. Because of its short aqueous half-life, MTSET solutions were freshly prepared before each study.

Cation Protection Assays—To determine whether the presence or absence of Na+ alters MTSET labeling, transiently transfected COS-1 cells were washed twice in either 1× phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4, or Na+-free buffer (MHBSS except choline chloride entirely substitutes NaCl) followed by incubation with MTSET (1 mm) prepared in either MHBSS or Na+-free buffer for 10 min at room temperature. After preincubation treatments, cells were washed twice in either MHBSS, pH 7.4, or Na+-free buffer and additionally equilibrated for 15 min at 37 °C in these buffers followed by determination of [3H]TCA uptake as described above. All control wells were treated identically. For each mutant transporter, uptake values were determined by taking a ratio of mutant uptake at each experimental condition versus mutant uptake for its respective unmodified control. We normalize mutant ratios to C270A by expressing mutant ratios for each condition as a percentage of C270A ratios calculated in the same manner.

MTSEA-biotin Labeling of Cysteine Mutants—COS-1 cells transiently expressing each mutant were washed twice with either MHBSS, pH 7.4, or Na+-free buffer (+/–sodium buffer) followed by incubation with 0.5 ml MTSEA-biotin (2 mm) prepared in +/–sodium buffer for 30 min at room temperature with rocking. For studies evaluating the effect of substrate on biotin labeling, cells were coincubated with both GDCA (1 mm) and MTSEA-biotin prepared in +/–sodium buffer as described above. For MTSET competition studies, cells were first preincubated with MTSET (1 mm) prepared in +/–sodium buffer for 10 min at room temperature, then washed twice with +/–sodium buffer followed by MTSEA-biotin labeling as described above. For each experiment, a 200 mm stock solution of MTSEA-biotin was prepared in DMSO and kept cold and dark until appropriately diluted with +/–sodium buffer just before use. After labeling, cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mm CaCl2, MgCl2, and 100 mm glycine and lysed with lysis buffer B (see “Protein Membrane Expression” methods for composition). Samples were eluted with streptavidin (100 μl) overnight at 4 °C with immunoblotting performed as described above. All MTSEA-biotinylation studies were repeated on two separate occasions (n = 2).

Data Analysis—For each mutant data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of at least three different experiments with triplicate measurements. Data analysis was performed with Graph-Pad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using either analysis of variance with Dunnett's post hoc test or Student's t test as appropriate. Data were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

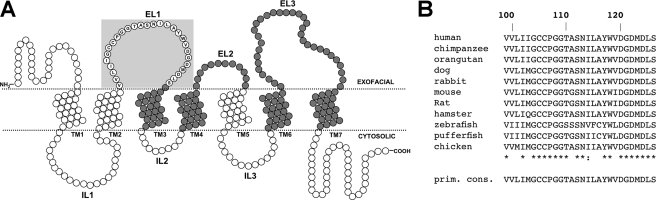

Cysteine Scan of EL1—As predicted by our topology model (25, 28), residues spanning Val-99—Ser-126 form the EL1 protein region, which exhibits high sequence conservation among a range of evolutionarily diverse species (Fig. 1). In the present study cysteines were consecutively introduced along EL1 (V99C–S126C) followed by structure-function assessments. Mutant P105C could not be constructed.

FIGURE 1.

Identity and sequence alignment of EL1 amino acids. A, secondary structural model of ASBT based on a 7-transmembrane (7TM) topology model. Each circle represents single amino acid residues comprising ASBT protein (348 residues total). Dotted lines indicate a lipid-aqueous interface (labeled), with large-scale protein features (i.e. ELs, transmembrane regions) indicated. Dark-shaded circles indicate residues previously submitted to cysteine-scanning and thiol modification. Residues comprising the EL1 region are encircled by a light blue square and contain their single-letter amino acid designation. B, sequence alignment of amino acids putatively comprising EL1 (Val-99—Ser-126) for known ASBT species. Sequences were retrieved from GenBank™ and aligned via the MULTALIN routine with annotation performed via MPSA. Numbering at the top indicates amino acid positioning relative to human ASBT. The bottom line indicates primary consensus for the EL1 region. Asterisks (*) denote complete preservation of residue.

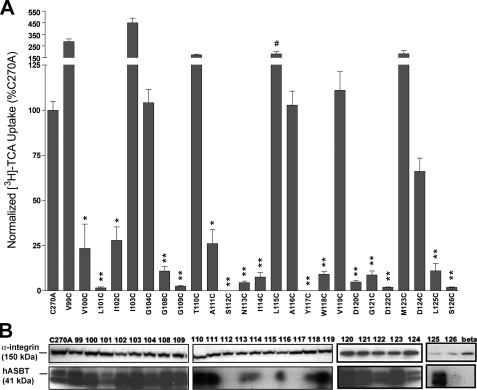

Transport Activity and Membrane Expression of Cysteine Mutants—Because of minimal background levels of bile acid transport (23), COS-1 cells were used for transient expression and [3H]TCA uptake analysis of EL1 mutant transporters. Protein surface expression was measured via biotin labeling with the membrane-impermeant sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin and immunoblotting followed by densitometry of developed protein bands (Fig. 2B). ASBT bands for each sample were standardized to an internal control (α-integrin) and expressed as a percentage of C270A intensity. Then, initial uptake activity was normalized to relative membrane expression for each mutant (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

[3H]TCA uptake activity and membrane expression of EL1 cysteine mutants. A, uptake of [3H]TCA was measured in COS-1 cells as described under “Experimental Procedures” and expressed as a percentage of the parental transporter, C270A. [3H]TCA uptake activity was normalized via densitometric analysis of the ratio of relative ASBT cell surface expression for cysteine mutants to the constitutively expressed internal membrane marker (α-integrin). Activity of mutant L115C was not normalized (#) due to high uptake activity despite cell surface expression levels below detectable limits. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. of three separate experiments with p ≤ 0.01 (**) and 0.05 (*), using analysis of variance with Dunnett's post hoc analysis. B, intact transfected COS-1 cells were treated with sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin as described under “Experimental Procedures” followed by Western blot processing. Blots were probed with the anti-hASBT antibody (1:30,000 dilution) followed by horseradish peroxide-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1:2000 dilution). Each blot was probed for the internal plasma membrane marker, α-integrin (150 kDa), and the absence of calnexin (90 kDa) (data not shown), an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein representing the negative control in the biotinylated fractions. Marker lanes are shown on the left side of the individual blots. Mature glycosylated hASBT visualizes as the 41-kDa band, whereas the lower, 38-kDa band (not indicated) represents the unglycosylated species.

Uptake activity for most mutants (64%) lining EL1 was significantly (p < 0.05) hampered (Fig. 2A), including two of the negatively charged aspartic acid residues thought to be important during transport (D120C, D122C). Lack of membrane expression accounted for loss-of-function only for mutants S112C, Y117C, and S126C (Fig. 2). Expression in whole cell extract was also absent for S112C and S126C (data not shown), suggesting defective protein synthesis or altered protein stability and folding leading to endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. In contrast, mutant Y117C exhibited detectable expression in whole cell extract, suggesting membrane trafficking or insertion defects. Remaining EL1 mutant transporters demonstrated measurable surface expression, with the notable exception of L115C (Fig. 2B). Despite uptake activity similar to control (Fig. 2A), mutant L115C displayed little measurable membrane expression in three separate assessments, although its expression in whole cell extract appears abundant (results not shown). Although surprising, it is possible that cysteine substitution at this position produced a “hyperactive” mutant transporter, which despite exceedingly low membrane expression, transports substrate at control levels. This may be due to substantially altered substrate turnover rates leading to uptake activity corresponding to control but at appreciably lower surface densities of transporter expression. All mutants with measurable uptake activity were further analyzed.

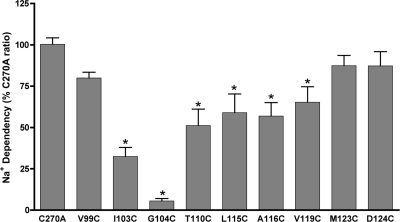

Na+ Sensitivity of Cysteine Mutants—By coupling the active translocation of one bile acid molecule to the flow of two Na+ ions down their electrochemical gradient, ASBT concentrates bile acids within the cell interior (31). Because previous studies implicate the EL1 region during Na+ recognition (16, 25, 26), we examined consequences of equilibrating (12 mm; i.e. [Na+]out = [Na+]in) sodium concentrations upon activity of all constructed cysteine mutants. For each mutant, the ratio of transport rates at equilibrating versus physiological (137 mm) Na+ concentrations was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the C270A Na+ ratio (Fig. 3). Potentially, defects in ability to bind Na+ or in coupling of Na+ to transport may be uncovered using this experimental protocol. The C270A parental construct displays a Na+ ratio of 0.70 ± 0.04 (data not shown), suggesting minimal alterations in Na+ dependence of the transporter upon alanine substitution of Cys-270. Uptake activity of V99C, M123C, and D124C was not affected at equilibrating [Na+] compared with control (Fig. 3), indicating minimal Na+ sensitivity for these sites. In contrast, mutants I103C, G104C, T110C, L115C, A116C, and V119C exhibited a significant (p < 0.05) loss of activity at lowered sodium concentrations (12 mm) (Fig. 3). Whether these residues play direct or indirect roles during sodium interactions is unclear at present. Because cysteine introduction poses a non-conservative amino acid change at these sites but yields minimal loss of activity at physiological [Na+] (Fig. 2), direct Na+ interactions are unlikely. Rather, indirect effects on Na+ dependence of the transporter may account for the results observed; for example, these residues may form interactions with other residues important for maintaining correct three-dimensional conformation of sodium binding sites. Alternatively, they may be involved in coupling sodium binding to later steps in the transport cycle.

FIGURE 3.

Sodium sensitivity of cysteine mutants. COS-1 cells expressing mutant transporters were incubated in uptake medium (5 μm [3H]TCA) containing equilibrating (12 mm) or physiological (137 mm) Na+ concentrations as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Sodium ratios were calculated for each mutant as the quotient of activity at 12 mm versus 137 mm [Na+] and expressed as a percentage of C270A. Bars represent mean activity ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p ≤ 0.01.

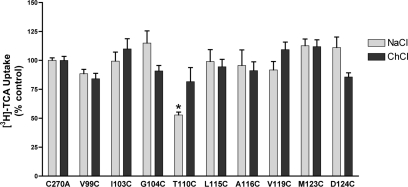

MTSET Sensitivity of EL1 Mutants—Intact COS-1 monolayers expressing mutant transporters were preincubated with 1 mm MTSET prepared in buffer containing either NaCl (“sodium buffer”) or choline chloride (“sodium-free buffer”) followed by several washes in appropriate buffer before evaluation of remaining [3H]TCA uptake activity. Presumably, only mutants with sulfhydryl groups facing an aqueous milieu (rather than lipid or internal protein environments) will form the more reactive (thiolate) species targeted by MTS reagents for modification (32). Surprisingly, despite its exofacial orientation, only one EL1 mutant (T110C; Fig. 4) was significantly affected upon MTSET (1 mm) application. Reversal of this inhibitory effect could be achieved for T110C by removing Na+ from the preincubation buffer, suggesting alternating accessibility of this residue mediated by Na+ binding (Fig. 4). Alternatively, thiol modification at T110C may be functionally silent when MTSET is applied in the absence of Na+. Functionally silent modification may also account for the lack of MTSET inhibition for the remainder of EL1 sites examined (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

MTSET labeling of EL1 cysteine mutants. Transiently transfected COS-1 cells expressing EL1 mutants were preincubated in buffer, pH 7.4, containing 1 mm MTSET prepared in buffer containing either 137 mm NaCl (light gray bar) or 137 mm choline chloride (dark gray bar) followed by [3H]TCA uptake as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Choline chloride does not activate the transporter and provides equimolar replacement for NaCl. All control wells were treated identically. Bars represent the mean ± S.D. of at least three separate measurements. Data are expressed as percentage of C270A values for each condition as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Student's t test analysis performed with p ≤ 0.01 (*).

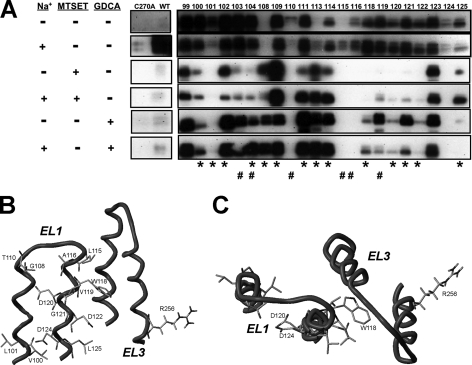

MTSEA-biotin Labeling of EL1 Mutants—Our substituted cysteine accessibility method studies in this manuscript thus far merely examined the functional effects of chemical modification with MTSET. However, residues that show no functional consequence of MTSET treatment may still be accessible to thiol modification by this reagent. Therefore, we evaluated whether EL1 cysteine mutants could be labeled with a biotin derivative, specifically MTSEA-biotin (Fig. 5A). In one set of studies labeling was done after preincubation with or without MTSET to determine whether MTSET and MTSEA-biotin bind the same sites. In another set of studies, labeling was done in the presence and absence of a natural high affinity ASBT substrate, GDCA (Km = 2.0 ± 0.4 μm) to determine whether bile acid substrates could protect against labeling. Finally, in all of these studies, reagents were prepared in both Na+-free and Na+-containing buffer to determine the effects of the co-transported sodium ion on cysteine labeling.

FIGURE 5.

MTSEA-biotin labeling of EL1 cysteine mutants. A, intact transfected COS-1 cells were treated with MTSEA-biotin (2 mm) in the indicated conditions. For MTSET competition studies, cells were first preincubated with MTSET (1 mm) prepared in buffer with and without sodium for 10 min at room temperature followed by MTSEA-biotin incubation as described under “Experimental Procedures.” For GDCA protection studies, coincubation of MTSEA-biotin (2 mm) with the bile acid substrate GDCA (1 mm) was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” All samples were then submitted to Western blot processing and blots were probed with the anti-hASBT antibody (1:30,000 dilution) followed by horseradish peroxide-linked anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (1:2000 dilution). ASBT is detected as two bands representing the mature glycosylated (41 kDa; top band) and unglycosylated (38 kDa, lower band) species. Negative (C270A) and positive (WT) controls are included to confirm specificity of reaction. Asterisks (*) denote sites with hampered activity upon cysteine mutation, whereas # signifies sodium-sensitive sites. B, in silico visualization (side view) of EL1 sites exhibiting GDCA protection from MTSEA-biotin labeling with respect to the EL3-localized Arg-256, previously implicated in bile acid interactions (21). GDCA protection predominantly occurs along EL1 distal segments, which include conserved aspartic acids Asp-120 and Asp-122, which may interact with sodium, and Asp-124, which putatively interacts with 7α-hydroxyl group of bile acids. C, top view of B.

To confirm the specificity of biotin labeling, both negative (C270A) and positive (WT) controls were included in our measurements for comparison. We have previously shown for WT protein that only Cys-270 can be labeled with MTSEA-biotin (23) and that the addition of bile acid substrates and/or removal of sodium protects against labeling (21). Similarly, alanine substitution of Cys-270 (C270A) eliminates detectable MTSEA-biotin labeling (23). Overall, all EL1 mutants (except G108C) are accessed to varying degrees by MTSEA-biotin (2 mm) (Fig. 5A), suggesting a high degree of solvent accessibility along this loop region. Visually apparent changes in MTSEA-biotin labeling as a function of Na+ binding were observed for mutants L101C, N113C, L115C, V119C, and L125C (Fig. 5A). Also noteworthy is the clear MTSEA-biotin labeling of L115C in the presence of sodium, which previously was not labeled by the lysine-specific biotin reagent, sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin. This unexpected result suggests greater labeling specificity of L115C using MTSEA-biotin; however, additional data are required for a definitive conclusion.

In studies wherein cells are first preincubated with MTSET (1 mm) followed by MTSEA-biotin exposure, biotin labeling for the majority of EL1 cysteine mutants (73%; 16 of 22 total) could be blocked by MTSET application (Fig. 5A). Only mutants G108C, G109C, N113C, I114C, M123C, and L125C did not exhibit decreased MTSEA-biotin labeling after MTSET preincubation, suggesting their inaccessibility to MTSET but not MTSEA-biotin. Accessibility of these sites may be governed by electrostatic constraints, since MTSET is positively charged at physiological pH, whereas MTSEA-biotin is electroneutral. Overall, these results demonstrate similar reactivity toward chemical modification by MTSET and MTSEA-biotin along most of the EL1 protein segment, further verifying the solvent-accessible nature of this loop segment. Moreover, the addition of sodium during MTSET preincubation alters blockage of biotin labeling predominantly for mutants clustered around one of the proposed sodium sensors, Asp-122 (i.e. V119C, D120C, G121C, D122C, D124C, L125C; Fig. 5A).

Finally, inclusion of the bile acid substrate GDCA during MTSEA-biotin incubation protected against labeling predominantly for sites lining the distal (or descending) loop segment (Fig. 5B). Moreover, of the 13 sites protected, 9 (V100C, L101C, G108C, W118C, D120C, G121C, D122C, D124C, L125C) are inactivated by cysteine mutation (Fig. 2A), corroborating their functional importance during ASBT transport. In silico visualization of these protected EL1 sites with respect to Arg-256 (localized to EL3), which we previously demonstrated in bile acid interaction (21), temptingly provides a spatial justification for our protection results (Fig. 5, B and C). Based on our model, residues exhibiting GDCA protection from biotin labeling are closely oriented toward EL3, suggesting a potential mechanism for bile acid interactions along these exofacial loop segments.

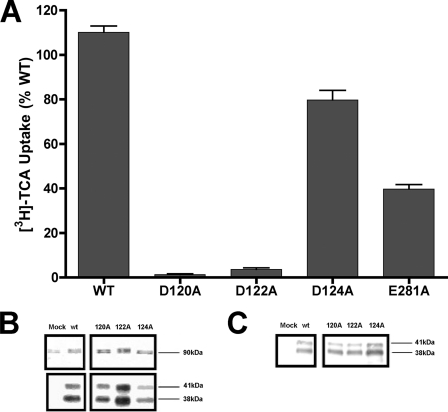

Asp-120 and Asp-122 Are Essential for Transport Function—To further delineate their roles in transporter structure and/or function, alanine substitutions were made along the cluster of negatively charged aspartic acids lining the distal segment of EL1 against the native WT template (D120A, D122A, D124A). Despite substantial membrane expression for all three mutants, transport activity of D120A and D122A was almost completely abolished (Fig. 6). In contrast, D124A exhibited minimal functional consequences from alanine replacement, similar to its tolerance for cysteine substitution (Fig. 2). Activity remaining after charge neutralization at Glu-281 (E281A; Fig. 6), a negatively charged residue previously implicated in transporter function (25), was included as positive control. From these data we can infer that charge neutralization at Asp-120 and Asp-122 (but not Asp-124) inactivates the transporter. The functional requirement for negative charge at Asp-120 is intriguing. Analysis of amino acid conservation with the SLC10A2 family demonstrates preservation of only Asp-122 among all members (SLC10A1–6); meanwhile, Asp-120 is only conserved in half of SLC10A members and, importantly, is replaced by a positive charge in NTCP (Lys-113), the hepatic Na+/bile acid co-transporter (16). Based on overall functional and structural similarity of ASBT and NTCP, it is unlikely that Asp-120 functions as a Na+ sensor, implicating highly conserved Asp-122 instead.

FIGURE 6.

Alanine-scanning of conserved EL1 aspartic acids. A, uptake of [3H]TCA was measured in COS-1 cells as described under “Experimental Procedures” and expressed as a percentage of the WT parental transporter. Intact transfected COS-1 cells were processed for whole cell (B) and cell surface protein expression (C) as described under “Experimental Procedures” followed by immunoblotting. Mature glycosylated (41 kDa) and unglycosylated (38 kDa) ASBT species are indicated. Mock represents vector-only samples.

Asp-124 Interacts with 7α-Hyroxyl Groups of the Cholestane Skeleton of Bile Acids—Because charge neutralization at Asp-124 did not abolish transport function, kinetic transport parameters for its mutants could be determined, including a subsequently constructed mutant with a conserved Asn replacement (D124N) (Table 1). Previously reported data for two functionally relevant mutants (E281A, E282D) are also shown for comparison (25). A significant decrease in TCA affinity (KT) compared with WT is observed for D124A, indicating overt defects during recognition and binding of bile acid substrate consequent to non-conserved Ala replacement at this site. However, a corresponding increase in Vmax normalizes the overall transporter “efficiency” (Vmax/KT) to approximately WT levels (Table 1), resulting in apparently unaffected uptake activity for the D124A mutant despite a dramatic loss in substrate affinity (Fig. 6). Intriguingly, conserved replacement with a highly polar residue (D124N) significantly mitigated this loss of substrate affinity, although KT remains higher than WT values (Table 1). Because these results suggest some role of Asp-124 during protein interactions with the prototypical substrate, TCA, we next sought to discover the nature of its participation using a variety of bile acid analogs differing in steroidal hydroxylation patterns and C-24 conjugation. Typically, hydroxylation patterns vary at the 7 or 12 positions on the steroidal nucleus of native bile acids; similarly, conjugation with either glycine or taurine may occur at the C-24 position. In general, an inverse correlation exists between bile acid inhibitory potency (as well as KT) and number of steroidal hydroxyl groups, with C-24 conjugation always improving Ki (and KT) of native bile acids; moreover, these C-24 effects dominate steroidal hydroxylation effects (33, 34). Using this rationale, four bile acid analogs with various patterns of 7- and 12-hydroxylation as well as C-24 conjugation were used in TCA uptake inhibition studies. Because of the dramatic effect on substrate affinity resulting from nonconserved Ala substitution, the D124A mutant was assayed and compared with two controls, namely WT and E281A. As shown in Table 2, calculated IC50 values for the native and E281A mutant transporters essentially conform to published inhibition hierarchies, with conjugated bile acids (TCDCA) demonstrating the greatest inhibitory potency and unconjugated, trihydroxy bile acids (cholic acid) demonstrating the least. In contrast, a reversal of this trend is observed for the D124A mutant, such that TCDCA exhibits the lowest potency, whereas IC50 values for DCA are not only the lowest, but are also significantly no different from WT values. Because only DCA lacks a 7α-hydroxyl group, two key points can be drawn from these data; (i) that substrate specificity of the D124A mutant is drastically altered from WT and (ii) that Asp-124 may interact with the 7α-hydroxyl group on the steroid nucleus of native bile acids, since IC50 values only for DCA were unaltered from WT control values. Similar to D124A, E281A control exhibits altered transport kinetics upon Ala substitution; however, we previously found no evidence of direct bile acid interaction at this site (21).

TABLE 1.

TCA kinetic constants for WT and Asp-124 mutants

COS-1 was transiently transfected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Uptake was measured at TCA concentrations ranging from 0 to 150 mm (measured in triplicate). Kinetic data were analyzed using SigmaPlot software with constants determined via nonlinear least-square fitting procedures.

| KT | Vmax | Vmax/KT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | pmol/min/mg protein | cm/s | |

| WT | 11.3 ± 1.9 | 312.5 ± 12.8 | 27.65 |

| D124A | 48.5 ± 6.2a | 1004.4 ± 50.9 | 20.71 |

| D124N | 30.1 ± 6.0a | 361.8 ± 24.2 | 12.00 |

| E281A | 19.6 ± 4.5a | 131.6 ± 9.0 | 6.7 |

| E282D | 12.3 ± 3.4 | 104.4 ± 7.5 | 8.4 |

p < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Summary of IC50 values of each bile acid analogue for WT and D124A

COS-1 cells were transiently transfected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” [3H]TCA (5 μm) uptake was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations (10 mm-0.01 m) of various bile acids. Kinetic data were analyzed using nonlinear least-squares fitting using SigmaPlot software with IC50 calculated using competitive inhibition kinetics.

|

IC50 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholic acid | DCA | CDCA | TCDCA | |

| mm | ||||

| 3α-OH | + | + | + | + |

| 7α-OH | + | - | + | + |

| 12α-OH | + | + | - | - |

| WT | 58 ± 9 | 34 ± 10 | 19 ± 4 | 11 ± 2 |

| D124A | 128 ± 27a | 44 ± 11 | 70 ± 6a | 154 ± 33a |

| E281A | 75 ± 15 | 48 ± 14 | 16 ± 4 | 15 ± 5 |

p < 0.05.

Dynamic Salt-bridging Mediated by Arg-254 Cooperatively Couples Na+ Binding—We analyzed potential long-range electrostatic interactions between EL1 and EL3 residues implicated during substrate and cation binding using a ASBT homology model (21). Potentially dynamic salt bridge pairs formed by Asp-122-Arg-254 and Arg-254-Glu-282 were identified as well as hydrogen bonding between Trp-118 and Glu-282. Based on these results, an R254A mutant was constructed against the WT native protein followed by kinetic assessments. Minimal changes in transport activity or bile acid affinity were observed for mutant R254A, suggesting that this residue does not interact with substrate (data not shown). However, the calculated Na+ ratio for R254A was significantly lower than control (p < 0.05), suggesting possible Na+ interactions for Arg-254 (Table 3). Subsequent sodium activation kinetics demonstrated significantly decreased Na+ affinity for the R254A mutant compared with WT as well as altered stoichiometry (Table 3). Sodium activation kinetics for the E281A mutant, which exhibits a lowered Na+ ratio but not altered sodium affinity or stoichiometry (25), are shown for comparison. Native ASBT typically co-transports two sodium ions per one bile acid molecule, with positive binding cooperativity for sodium such that one sodium binding enhances binding affinity for the second sodium. Ala substitution of Arg-254 disrupts normal sodium binding interactions, suggesting that Arg-254 may participate in the sequence of events cooperatively coupling binding of the two co-transported sodium ions.

TABLE 3.

Sodium activation kinetics for WT and R254A mutant

[3H]TCA uptake into transfected COS-1 cells was measured at increasing Na+ concentrations using choline chloride as an equimolar replacement for NaCl. Kinetic constants were calculated using Hill equation: V = Vmax[Na]n/([Na]n + KNan).

| Na+ ratio | KNa | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | |||

| WT | 0.62 ± 0.058 | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.3 |

| E281A | 0.43a ± 0.018 | 12.3 ± 1.7 | 2.2 ± 0.5 |

| R254A | 0.18a ± 0.015 | 22.4a ± 1.3 | 3.0* ± 0.5 |

DISCUSSION

Presently, we demonstrate the functional importance of residues lining the large extramembranous loop EL1 during recognition and binding of ASBT substrates; in particular, negatively charged aspartic acids clustered along distal loop segments may be essential for both Na+ and bile acid binding events. Furthermore, cooperative binding of two co-transported Na+ ions along spatially disparate protein sites may be mediated in part by dynamic dipole-dipole and salt-bridging interactions along EL1 and EL3 loop segments. Our conclusions integrate data accumulated from substituted cysteine accessibility analysis, site-directed mutagenesis, and in silico predictions (21, 25).

Cys-scanning along EL1 (Val-99—Ser-126) yielded mutant transporters for which the majority (64%) had significantly impaired activity or loss of transport function (16 of 25 mutants; Fig. 2A). Similar intolerance to Cys replacement was noted during earlier substituted cysteine accessibility analysis of another large loop region EL3, found to interact with both Na+ and bile acid substrates (21). Transport defects for most EL1 mutants stem from functional rather than structural perturbations of the transport cycle, since only three mutants exhibited simultaneous decreases in protein expression and activity (S112C, Y117C, S126C; Fig. 2B).

In the absence of a crystal structure, the structure-function and substrate affinity of ASBT have been analyzed vis á vis the protein using homology modeling techniques or from the perspective of the substrate via pharmacophore and three-dimensional-quantitative structure-activity relationship techniques. The ASBT substrate pharmacophore comprises five key molecular features that promote substrate-transporter affinity, including (i) one hydrogen bond (HB) donor, (ii) one HB acceptor, and (iii) three hydrophobic features (35, 36). For TCA, these features correspondingly map to (i) either the 7- or 12-hydroxyl groups, (ii) the negatively charged group on the C-24 side chain, and (iii) ring D and the adjacent methyl group at C-18 (one hydrophobic feature) and the 21-methyl group of the side chain (second hydrophobic feature). Note that substrate binding and translocation does not require fulfillment of all five features simultaneously. As mapped to the protein, our studies have putatively identified residues satisfying the first two features (21, 23–25); studies with ASBT orthologs and paralogs corroborate these assignments (26, 27, 37). However, there has been minimal progress toward identification of apolar residues involved in hydrophobic substrate-protein interactions. Consequently, our current results are particularly noteworthy, as the majority (71%) of inactivated EL1 residues are hydrophobic (12 of 17 mutants; Fig. 2A). By comparison, a significantly smaller proportion of functionally critical hydrophobic sites (44%) was identified along the EL3 protein segment (21). This observed asymmetry tempts speculation that EL1 residues provide the requisite hydrophobic surfaces predicted by the latter three features of pharmacophore models. Such a conclusion would be spatially coherent, since our previous studies suggest substrate binding occurs along protein loop regions rather than within a interior hydrophilic cavity, as proposed for Lac permease (38). Although further studies are necessary for unequivocal identification of these protein elements, our mutagenesis data strongly highlight the importance of hydrophobic residues along EL1 that may form bile acid contact points during substrate binding steps.

Also anticipated from pharmacophore models, charged and/or polar residues are required for substrate affinity. We previously identified two negatively charged EL3 residues (Glu-261, Glu-282) and an aromatic group (Phe-278) likely mediating Na+ interactions with the protein, whereas another positively charged residue (Arg-256) may function as the hydrogen bond donor predicted to interact with the negatively charged bile acid side chain (21, 25). In the present study the cluster of negatively charged aspartic acids lining the distal segment of EL1 (Asp-120, Asp-122, Asp-124) may play roles in both bile acid and sodium interactions. Specifically, neutralization of negative charge at Asp-120 and Asp-122 inactivated the transporter without affecting protein expression; in contrast, Asp-124 mutants retained measurable TCA transport activity (Figs. 2 and 6). However, significantly decreased bile acid affinity was observed for D124A compared with native protein (Table 1), suggesting substrate interactions at this position. Restoration of polar character via Asn replacement supports this conclusion, since D124N exhibits significantly improved TCA affinity compared with mutant D124A even though KT did not return to control values (Table 1). To determine the nature of bile acid interactions, D124A inhibition studies were conducted using various bile acid analogues differing in steroidal hydroxylation and C-24 conjugation. Compared with the native protein, the D124A mutant exhibited significantly increased IC50 values for all bile acid analogs except DCA (Table 2), which is unique among bile acids assayed in lacking a 7α-OH group. Thus, we hypothesize that Asp-124 interacts with 7α-OH groups on the cholestane skeleton and maps to the hydrogen bond acceptor feature predicted by pharmacophore models. Based on our structural model, mapping of the hydrogen bond acceptor and donor features to Asp-124 and Arg-256, respectively, appears plausible based on their relative spatial proximity and orientation. Additional validation of bile acid interactions along Asp-124 can be derived from our results for GDCA (glycodeoxycholic acid) protection against MTSEA-biotin labeling along the EL1 protein segment (Fig. 5). In these studies the addition of GDCA (1 mm) during MTSEA-biotin incubation substantially decreased the extent of labeling predominantly along distal (descending) EL1 sites (Fig. 5, B and C), including Asp-124. These results suggest the physical proximity of bile acid binding sites in and/or around EL1 sites that include Asp-124.

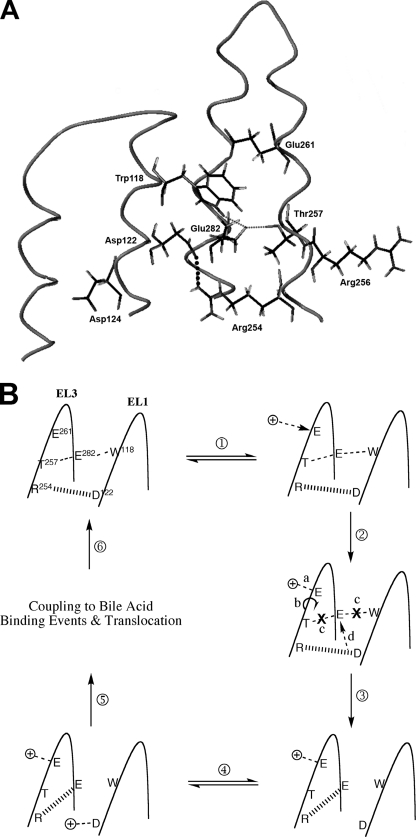

Long-range electrostatic recognition and binding of the two co-transported sodium ions is likely mediated by negatively charged protein residues, suggested as Glu-261 and Asp-122 for ASBT ortho- and paralogs (16, 26, 27) and corroborated by us previously (21) and here (Figs. 2 and 6) for human ASBT. Using our homology model, the relative spatial orientation and proximity of residues lining the EL1 and EL3 loop segments were visualized, and potential tertiary interactions among them were determined. Our analysis reveals putative dynamic salt bridge pairs between Asp-122 and Arg-254 and between Arg-254 and Glu-282 in addition to a hydrogen bonding pair between Glu-282 and Trp-118 (Fig. 7A). In our current study we demonstrate the functional importance of Asp-122 and Trp-118, since alanine and/or cysteine replacement inactivates the transporter without altering protein expression (Figs. 2 and 6). Moreover, our previous studies indicate (i) functional requirement of negative charge at position 282 (25), (ii) functionally critical hydrogen bonding between Glu-282 and Thr-257 (21,; and (iii) proximity of Arg-254 around sodium binding cavities (21). To more thoroughly examine the role of Arg-254 during ASBT transport, sodium activation kinetics were determined for R254A. Compared with WT control, the R254A mutant displays significantly decreased sodium affinity and altered stoichiometry (Table 3), confirming its position within sodium binding sites. Integrating experimental data and in silico predictions, we posit that Arg-254 couples the binding of sodium ions at their respective binding sites, Glu-261 and Asp-122, by forming dynamic salt bridges alternately with Asp-122 followed by Glu-282. The following illustrates a thermodynamically simple scenario (Fig. 7B). (i) Initial protein state before Na+ binding events includes a salt bridge pair between Arg-254 and Asp-122 and simultaneous hydrogen bonding between Thr-257 and Glu-282 and between Glu-282 and Trp-118; these intramolecular interactions contribute to proper tertiary structure of the EL1-EL3 protein regions promoting binding of one sodium at Glu-261. (ii) One sodium binds at Glu-261. (iii) This Glu-261 binding event is sensed by Thr-257, situated along the same helical face, leading to structural distortions that disturb the hydrogen-bonding triad (Thr-257-Glu-282-Trp-118). (iii) As a result, loss of hydrogen bonding among the Thr-257-Glu-282-Trp-118 triad and salt bridging between Asp-122 and Arg-254 occurs. (iv) Arg-254 is now available for salt-bridging with Glu-282, whereas Asp-122 is electrostatically vacant for subsequent sodium interactions. Because Trp-118 and Asp-122 share the same helical face, structural changes transduced along the EL1 helix after loss of Trp-118-Glu-282 hydrogen bonding may promote sodium binding as well. (v) Finally, second sodium binds at Asp-122. Presently, the sequence of events ensuing after binding of both co-transported sodium ions remains unclear; presumably, binding of cations and bile acids couples in some manner via an ordered binding mechanism, after which the fully loaded carrier undergoes widespread structural rearrangement leading to eventual translocation. In the above mechanism, whereas certain details are speculative, our data nonetheless corroborate its general thrust, particularly wherein Arg-254 represents a crucial link along the series of steps catalyzing the cooperative binding of two sodium ions along spatially disparate protein regions. It should be noted that, because cooperative binding events are highly complex processes, this proposed mechanism does not preclude participation of auxiliary residues or formation of flexible networks of successive interactions leading to coupled sodium binding. Indeed, the strategic abundance of functionally essential Gly residues along both EL3 (21) and EL1 (Gly-108, Gly-109, Gly-121; Fig. 2) supports this latter observation; potentially, these residues can impart a high degree of flexibility along loop regions during dynamic structural changes predicted by the proposed mechanism.

FIGURE 7.

In silico model of EL1-EL3 tertiary interactions and predicted Na+ binding mechanism. A, in silico depiction of residues lining EL1 and EL3 loop segments putatively involved during sodium and bile acid binding events. Asp-124 and Arg-256 map, respectively, to hydrogen bond donor and acceptor features of ASBT pharmacophore models (35, 36), whereas Asp-122 and Glu-261 may function as sodium sensors. Small dotted lines denote the hydrogen-bonding triad (T257-E282-W118), whereas the large dotted line represents salt bridging interaction between Asp-122 and Arg-254; these interactions represent initial protein state for proposed sodium binding mechanism. B, proposed mechanism for cooperative binding of two sodium ions at predicted sodium sensors, Asp-122 and Glu-282. Steps are as follows. 1, initial protein state, wherein simultaneous hydrogen bonding exists among Thr-257 andGlu-282 and among Glu-282 and Trp-118; 2a, the first sodium ion binds at the sodium sensor Glu-261; 2b, sodium binding is sensed along the EL3 loop segment, and structural changes associated with Glu-261 binding transduce the length of the helical face, along which Thr-257 is located; 2c, these structural distortions disrupt the hydrogen bonding triad Thr-257-Glu-282-Trp-118, while simultaneously interrupting salt bridge interaction between Asp-122 and Arg-254; 2d, positive charge at Arg-254 now electrostatically vacant for subsequent salt bridging with available negative charge at Glu-282; 3, Arg-254 salt bridge interaction transferred to Glu-282 (because Trp-118 and Asp-122 line the same helical face, structural shifts along EL1 after loss of the hydrogen-bonding triad may also promote spatial availability of Asp-122 for interactions with second sodium ion); 4, second sodium ion binds at Asp-122, the second sodium sensor; 5, coupling of sodium and bile acid binding events after which the fully loaded carrier undergoes conformational changes in protein structure leading to translocation; 6, reorientation of the empty carrier to an outward facing conformation and initial protein state.

Additional verification for participation of EL1 residues during ligand interactions derives from Na+ sensitivity assays and thiol modification of introduced cysteine residues. Of the mutants tolerant to mutation, the majority (60%) exhibited significantly hampered activity at equilibrating (12 mm) versus physiological (137 mm) sodium concentrations (Fig. 3), suggesting their proximity to sodium binding regions and substantiating the proposed sodium-sensing role of Asp-122. Furthermore, upon sodium binding, local protein environments may undergo dynamic conformational changes. Using cysteine-scanning, the free sulfhydryl of the introduced cysteine can theoretically provide a monitor recording such dynamic protein changes, particularly in response to binding events. In the present study, instead of relying only on functional assays to confirm chemical modification of introduced thiols (Fig. 4), we also used a biotin derivative, MTSEA-biotin, to circumvent the possibility of functionally silent labeling (Fig. 5) and to better illustrate the dynamic changes in protein accessibility to MTS reagents. Our studies confirm the highly solvent-accessible nature of the EL1 loop region and suggest the occurrence of dynamic changes in accessibility of specific sites consequent to sodium and bile acid binding events (Fig. 5). Such effects have been reported for other ion-coupled solute transporters (19, 39) and would follow logically during the ASBT transport cycle as well. Moreover, these results provide experimental evidence for proximity of EL1 residues within or around ligand binding cavities. In particular, alternating accessibility of Trp-118, Asp-120, Asp-122, and Asp-124 to MTS labeling in response to the binding of bile acids and/or sodium (Fig. 5) strongly suggests their propinquity to ASBT-substrate binding surfaces and infers their participation during binding events.

In summary, we report a novel mechanism for the Na+-substrate translocation sequence mediated by ASBT based on our systematic analysis of residues lining the EL1 protein segment, including the interaction of Asp-124 with 7α-OH groups of bile acids and the mapping of apolar residues to hydrophobic interactions predicted by published ASBT pharmacophores; moreover, Asp-122 likely forms one of two sodium sensors during sodium/bile acid cotransport.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. H. Kakoshka for invaluable input during preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant DK61425 (to P. W. S.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ASBT, apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter II; hASBT, human ASBT; TCA, taurocholic acid; EL, extracellular loop; DCA, deoxycholic acid; CDCA, chenodeoxycholic acid; GDCA, glycodeoxycholic acid; MTS, methanethiosulfonate; MTSEA-biotin, 2-((biotinoyl)amino)ethylmethanethiosulfonate; MTSET, [2-(trimethylammonium)ethyl]-methanethiosulfonate bromide; TCDCA, taurochenodeoxycholic acid; WT, wild type; sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin, sulfosuccinimidyl-2 (biotinamido)ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate.

References

- 1.Pauli-Magnus, C., Stieger, B., Meier, Y., Kullak-Ublick, G. A., and Meier, P. J. (2005) J. Hepatol. 43 342–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballatori, N., Christian, W. V., Lee, J. Y., Dawson, P. A., Soroka, C. J., Boyer, J. L., Madejczyk, M. S., and Li, N. (2005) Hepatology 42 1270–1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson, P. A., Hubbert, M., Haywood, J., Craddock, A. L., Zerangue, N., Christian, W. V., and Ballatori, N. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 6960–6968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trauner, M., and Boyer, J. L. (2003) Physiol. Rev. 83 633–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang, H. C., Tremont, S. J., Lee, L. F., Keller, B. T., Carpenter, A. J., Wang, C. C., Banerjee, S. C., Both, S. R., Fletcher, T., Garland, D. J., Huang, W., Jones, C., Koeller, K. J., Kolodziej, S. A., Li, J., Manning, R. E., Mahoney, M. W., Miller, R. E., Mischke, D. A., Rath, N. P., Reinhard, E. J., Tollefson, M. B., Vernier, W. F., Wagner, G. M., Rapp, S. R., Beaudry, J., Glenn, K., Regina, K., Schuh, J. R., Smith, M. E., Trivedi, J. S., and Reitz, D. B. (2005) J. Med. Chem. 48 5853–5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitayama, K., Nakai, D., Kono, K., van der Hoop, A. G., Kurata, H., de Wit, E. C., Cohen, L. H., Inaba, T., and Kohama, T. (2006) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 539 89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlattjan, J. H., Fehsenfeld, H., and Greven, J. (2003) Arzneim. Forsch. 53 837–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West, K. L., McGrane, M., Odom, D., Keller, B., and Fernandez, M. L. (2005) J. Nutr. Biochem. 16 722–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West, K. L., Ramjiganesh, T., Roy, S., Keller, B. T., and Fernandez, M. L. (2002) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 303 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alrefai, W. A., Sarwar, Z., Tyagi, S., Saksena, S., Dudeja, P. K., and Gill, R. K. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. 288 G978–G985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang, J. Y., Kimmel, R., and Stroup, D. (2001) Gene (Amst.) 262 257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huff, M. W., Telford, D. E., Edwards, J. Y., Burnett, J. R., Barrett, P. H., Rapp, S. R., Napawan, N., and Keller, B. T. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22 1884–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, H., Xu, G., Shang, Q., Pan, L., Shefer, S., Batta, A. K., Bollineni, J., Tint, G. S., Keller, B. T., and Salen, G. (2004) Metabolism 53 927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteside, C. H., Fluckiger, H. B., and Sarett, H. P. (1966) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 121 153–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balakrishnan, A., and Polli, J. E. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 3 223–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geyer, J., Wilke, T., and Petzinger, E. (2006) Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 372 413–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swaan, P. W., Hillgren, K. M., Szoka, F. C., Jr., and Oie, S. (1997) Bioconjugate Chem. 8 520–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan, L., and Kaback, H. R. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 35 67–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guan, L., and Kaback, H. R. (2007) Nat. Protoc. 2 2012–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaback, H. R., Dunten, R., Frillingos, S., Venkatesan, P., Kwaw, I., Zhang, W., and Ermolova, N. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad Sci U. S. A. 104 491–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee, A., Hussainzada, N., Khandelwal, A., and Swaan, P. W. (2008) Biochem. J. 410 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee, A., Ray, A., Chang, C., and Swaan, P. W. (2005) Biochemistry 44 8908–8917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussainzada, N., Banerjee, A., and Swaan, P. W. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70 1565–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussainzada, N., Khandewal, A., and Swaan, P. W. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73 305–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang, E. Y., Phelps, M. A., Banerjee, A., Khantwal, C. M., Chang, C., Helsper, F., and Swaan, P. W. (2004) Biochemistry 43 11380–11392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun, A. Q., Balasubramaniyan, N., Chen, H., Shahid, M., and Suchy, F. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 16410–16418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zahner, D., Eckhardt, U., and Petzinger, E. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270 1117–1127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banerjee, A., and Swaan, P. W. (2006) Biochemistry 45 943–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell, S. M., Lee, E., Garcia, M. L., and Stephan, M. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 24089–24099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong, M. H., Oelkers, P., and Dawson, P. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 27228–27234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinman, S. A., Carruth, M. W., and Dawson, P. A. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 34691–34695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlin, A., and Akabas, M. H. (1998) Methods Enzymol. 293 123–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balakrishnan, A., Wring, S. A., and Polli, J. E. (2006) Pharmacol. Res. 23 1451–1459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balakrishnan, A., Wring, S. A., Coop, A., and Polli, J. E. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 3 282–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swaan, P. W., Szoka, F. C., Jr., and Oie, S. (1997) J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11 581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baringhaus, K. H., Matter, H., Stengelin, S., and Kramer, W. (1999) J. Lipid. Res. 40 2158–2168 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kramer, W., Girbig, F., Glombik, H., Corsiero, D., Stengelin, S., and Weyland, C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 36020–36027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abramson, J., Smirnova, I., Kasho, V., Verner, G., Kaback, H. R., and Iwata, S. (2003) Science 301 610–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pajor, A. M., and Randolph, K. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 18728–18735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]