Abstract

Naturally occurring mutations in the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel/ryanodine receptor RyR1 are linked to malignant hyperthermia (MH), a life-threatening complication of general anesthesia. Although it has long been recognized that MH results from uncontrolled or spontaneous Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, how MH RyR1 mutations render the sarcoplasmic reticulum susceptible to volatile anesthetic-induced spontaneous Ca2+ release is unclear. Here we investigated the impact of the porcine MH mutation, R615C, the human equivalent of which also causes MH, on the intrinsic properties of the RyR1 channel and the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release during store Ca2+ overload, a process we refer to as store overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR). Single channel analyses revealed that the R615C mutation markedly enhanced the luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1. Moreover, HEK293 cells expressing the R615C mutant displayed a reduced threshold for SOICR compared with cells expressing wild type RyR1. Furthermore, the MH-triggering agent, halothane, potentiated the response of RyR1 to luminal Ca2+ and SOICR. Conversely, dantrolene, an effective treatment for MH, suppressed SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing the R615C mutant, but not in cells expressing an RyR2 mutant. These data suggest that the R615C mutation confers MH susceptibility by reducing the threshold for luminal Ca2+ activation and SOICR, whereas volatile anesthetics trigger MH by further reducing the threshold, and dantrolene suppresses MH by increasing the SOICR threshold. Together, our data support a view in which altered luminal Ca2+ regulation of RyR1 represents a primary causal mechanism of MH.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH)3 is an autosomal dominant, pharmacogenetic disorder of skeletal muscle. MH is triggered by volatile anesthetics (e.g. halothane) and depolarizing muscle relaxants and is characterized by muscle rigidity and a hyper-metabolic state (1–5). MH also occurs in pigs, in which it is caused by stress and known as porcine stress syndrome (6, 7). A single point mutation, R615C, in the pig skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor RyR1 is responsible for all cases of porcine MH (6, 7). On the other hand, human MH has been linked to a large number of mutations in RyR1 (4, 5, 8). Some human RyR1 mutations have also been linked to central core disease, which is often associated with MH. Although the genetic basis of MH has been well defined, the molecular mechanisms by which RyR1 mutations confer MH susceptibility and volatile anesthetics and stress trigger MH are not completely understood.

The pig model has proven invaluable in investigating the molecular basis of MH, and these studies have consistently demonstrated that Ca2+ release from MH-susceptible (MHS) pig skeletal muscle or sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane vesicles is enhanced upon exposure to various stimuli (1, 4, 9–14). However, to date no clear mechanistic basis of this enhanced responsiveness of MHS RyR1 channels to stimuli has emerged. For example, some studies reported that this enhanced activity of MHS RyR1 channels was associated with changes in the apparent sensitivity of the channel to cytosolic Ca2+ or Mg2+, whereas others found no marked difference in the apparent sensitivity to cytosolic Ca2+ activation between MHS and normal RyR1 channels (1, 13–20). Hence, the intrinsic properties of the RyR1 channel that are altered by the MH R615C mutation have remained undefined.

Increasing evidence has highlighted the importance not only of cytosolic Ca2+, but also of luminal Ca2+, in controlling the activity of the RyR channel (21–23). However, in comparison with the extensive investigations of the sensitivity of MHS RyR1 channels to cytosolic Ca2+ and Mg2+, the effects of the MH R615C mutation on the luminal Ca2+ sensitivity of the channel remain largely unexplored. A notable exception is found among the earliest work investigating the effect of the MH R615C mutation on Ca2+ handling by isolated SR membranes (13, 24, 25). Nelson and colleagues (13, 24, 25) originally reported that the luminal Ca2+ load required to trigger spontaneous SR Ca2+ release was markedly reduced in SR membranes isolated from MHS animals, suggesting that a defect in intraluminal Ca2+ regulation may underlie MH.

We have recently shown that disease-causing mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor RyR2 increase the sensitivity of the channel to activation by luminal Ca2+ and enhance the propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ release during store Ca2+ overload, a process we have termed store overload-induced Ca2+ release (SOICR) (26, 27). Interestingly, disease-linked RyR2 mutations are located in regions corresponding to the MH/central core disease mutation regions in RyR1 (28). This similar distribution suggests that disease-linked RyR2 and RyR1 mutations may exert similar effects on the intrinsic properties of the channel. To test this hypothesis, in the present study, we assessed the impact of the MH R615C mutation and the MH-triggering agent, halothane, on the response of RyR1 to luminal Ca2+ and the propensity for SOICR. We found that the R615C mutation and halothane potentiated luminal Ca2+ response and SOICR. On the other hand, dantrolene, the only treatment for MH, suppressed SOICR. We propose that a reduced threshold for SOICR as a result of augmented luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1 represents a primary defect underlying the pathogenesis of MH.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutagenesis—The R615C RyR1 MH mutation in the rabbit RyR1 cDNA was made by the PCR-based overlap extension method (29). The sequence of the PCR-amplified region was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The full-length RyR1 wt and R615C mutant cDNAs were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.

Single Channel Recordings—Pig RyR1 wt and R615C mutant proteins were partially purified from normal and MHS pig SR microsomes by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Heart phosphatidylethanolamine and brain phosphatidylserine (Avanti Polar Lipids), dissolved in chloroform, were combined in a 1:1 ratio (w/w), dried under nitrogen gas, and suspended in 30 μl of n-decane at a concentration of 12 mg lipid/ml. Bilayers were formed across a 250-μm hole in a Delrin partition separating two chambers. The trans chamber (800 μl) was connected to the head stage input of an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Austin, TX). The cis chamber (1.2 ml) was held at virtual ground. A symmetrical solution containing 250 mm KCl and 25 mm Hepes (pH 7.4), was used for all recordings, unless indicated otherwise. A 4-μl aliquot (≈1 μg of protein) of the sucrose density gradient-purified wt or mutant RyR1 proteins was added to the cis chamber. Spontaneous channel activity was always tested for sensitivity to EGTA and Ca2+. The chamber to which the addition of EGTA inhibited the activity of the incorporated channel presumably corresponds to the cytoplasmic side of the Ca2+ release channel. The direction of single channel currents was always measured from the luminal to the cytoplasmic side of the channel, unless mentioned otherwise. Recordings were filtered at 5,000 Hz. Data analyses were carried out using the pclamp 8.1 software package (Axon Instruments). Free Ca2+ concentrations were calculated using the computer program of Fabiato and Fabiato (30).

Generation of Stable, Inducible HEK293 Cell Lines—Stable, inducible HEK293 cell lines expressing RyR1 wt and the R615C mutant were generated using the Flp-In T-REx core kit from Invitrogen. Briefly, the full-length cDNA encoding the RyR1 wt or mutant channel was subcloned into the inducible expression vector, pcDNA5/FRT/TO (Invitrogen). Flp-In T-REx-293 cells were then co-transfected with the inducible expression vector containing the RyR1 wt or mutant cDNA and the pOG44 vector encoding the Flp recombinase in 1:5 ratios using the Ca2+ phosphate precipitation method. Transfected cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (137 mm NaCl, 8 mm Na2HPO4, 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 2.7 mm KCl) 1 day after transfection and allowed to grow for 1 more day in fresh medium. The cells were then washed again with phosphate-buffered saline, harvested, and plated onto new dishes. After the cells had attached (∼ 4 h), the growth medium was replaced with a selective medium containing 200 μg/ml hygromycin (Invitrogen). The selective medium was changed every 3–4 days until the desired number of cells was grown. The hygromycin-resistant cells were pooled, aliquoted, and stored at –80 °C. These positive cells are believed to be isogenic, because the integration of the RyR1 cDNA is mediated by the Flp recombinase at a single target site. Each HEK293 cell line was tested for RyR1 expression using Western blotting analysis and immunocytofluorescence staining.

Single Cell Ca2+ Imaging (Cytosolic Ca2+)—Intracellular Ca2+ transients in stable inducible HEK293 cells expressing the RyR1 wt or the R615C mutant channels were measured using single-cell Ca2+ imaging and the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator dye fura-2 acetoxymethyl ester (AM) as described previously (26). Cells grown on glass coverslips for 24 h after induction by 1 mg/ml tetracycline (Sigma) were loaded with 5 μm fura-2 AM in Krebs-Ringer-Hepes (KRH) buffer (125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 6 mm glucose, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 25 mm Hepes, pH 7.4) plus 0.02% pluronic F-127 (Molecular Probes) and 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin for 20 min at room temperature. The coverslips were then mounted in a perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) on an inverted microscope (Nikon TE2000-S) equipped with an S-Fluor 20×/0.75 objective. The cells were continuously perfused with KRH buffer containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0.2–10 mm) at room temperature. 10 mm caffeine was applied at the end of each experiment to confirm the expression of active RyR1 channels. Time lapse images (0.33 frames s–1) were captured and analyzed with the Compix Inc. Simple PCI6 software.

Single Cell Ca2+ Imaging (Luminal Ca2+)—To monitor PCI6 luminal Ca2+ transients in HEK293 cells, we used the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based cameleon protein D1ER (31). Stable, inducible HEK293 cells expressing RyR1 wt or mutant channels were transfected using the Ca2+ phosphate precipitation method, with D1ER cDNA 24 h before the induction of RyR1 expression. The cells were perfused continuously with KRH buffer (125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 6 mm glucose, 1.2 mm MgCl2, 25 mm Hepes, pH 7.4) containing various concentrations of CaCl2 (0 or 5 mm) and tetracaine (1 mm) or caffeine (20 mm) at room temperature. The images were captured with Compix Inc. Simple PCI 6 software at 470- and 535-nm emission, with excitation at 430 nm, every 2 s using an inverted microscope (Nikon TE2000-S) equipped with a S-Fluor 20×/0.75 objective. The amount of FRET was determined from the ratio of the emissions at 535 and 470 nm.

RESULTS

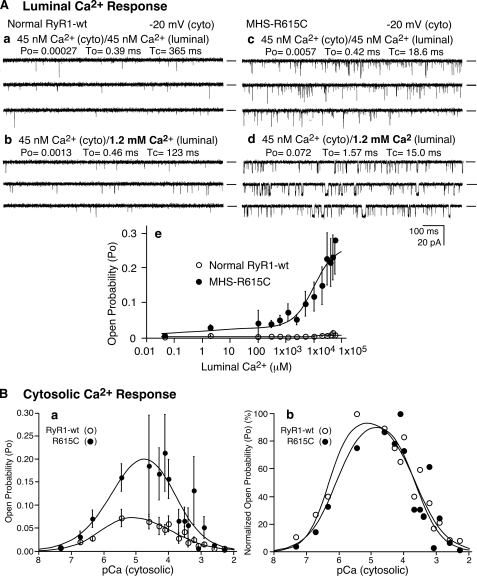

The Porcine MH R615C Mutation Enhances the Luminal Ca2+ Activation of Single RyR1 Channels—To directly assess the impact of the R615C mutation on luminal Ca2+ activation, we incorporated single normal (RyR1 wt) and MHS (RyR1-R615C) RyR1 channels into planar lipid bilayers and examined their responses to increasing concentrations of luminal Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 1A, elevating the luminal Ca2+ concentration from ∼45 nm to 50 mm had little effect on single wt channels but markedly activated single R615C mutant channels with an activation threshold of about 0.5 mm luminal Ca2+ (Fig. 1A, panel e). For instance, at 1.2 mm luminal Ca2+, the average open probability (Po) for single R615C mutant channels was 0.070 ± 0.024 (n = 14) (Fig. 1A, panel d), which was significantly greater than that of single wt channels (0.001 ± 0.0004, n = 8) (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1A, panel b). These observations directly demonstrate that the R615C mutation enhances the response of the RyR1 channel to luminal Ca2+ activation.

FIGURE 1.

Single RyR1 channels from normal and MHS pig SR differ in their responses to luminal Ca2+. A, the activities of single RyR1 channel from normal (panels a and b) and MHS (panels c and d) pig skeletal muscle SR were recorded in a symmetrical recording solution containing 250 mm KCl and 25 mm Hepes (pH 7. 4) at a holding potential of –20 mV. The Ca2+ concentration on both the cytosolic and luminal sides of the channel was adjusted to ∼45 nm (panels a and c). The luminal Ca2+ concentration was then increased to various levels by the addition of aliquots of CaCl2 solution. Single-channel current traces at 1.2 mm luminal Ca2+ are shown (panels b and d). The relationships between Po and luminal Ca2+ concentrations are shown in panel e. The data points are the means ± S.E. from 8 wt and 14 R615 single channels. Openings are downward. The open probability (Po), arithmetic mean open time (To), and arithmetic mean closed time (Tc) are indicated on the top of each panel. B, the response of normal and MHS RyR1 channels to cytosolic Ca2+. The responses of normal (RyR1 wt) and MHS (R615C) to cytosolic Ca2+ were assessed using single channel recordings. The luminal Ca2+ concentration was kept at 45 nm. Panel a shows relationships between open probability (Po) and cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (pCa) of single wt (open circles) and single R615C mutant (solid circles) channels. The normalized (100%) Po-pCa relationships are shown in panel b. The data points shown are the means ± S.E. from 10 wt and 10 R615C mutant channels.

The R615C Mutation Has Little Effect on the Cytosolic Ca2+ Dependence of Single RyR1 Channels—We next determined the response of wt and R615C to cytosolic Ca2+ using single channel recordings. As shown in Fig. 1B, both single wt and R615C channels were maximally activated by ∼10 μm cytosolic Ca2+ with an activation threshold about ∼100 nm and were completely inhibited by ∼5 mm Ca2+. Although the extent of maximum activation of the R615C channels by cytosolic Ca2+ was greater than that of the wt channels (Fig. 1B, panel a), the cytosolic Ca2+ dependence of activation or inactivation of the wt and R615C channels was similar, as seen from the normalized Ca2+ responses (Fig. 1B, panel b). These observations indicate that the R615C mutation does not markedly alter the sensitivity of single RyR1 channels to cytosolic Ca2+ activation or inactivation.

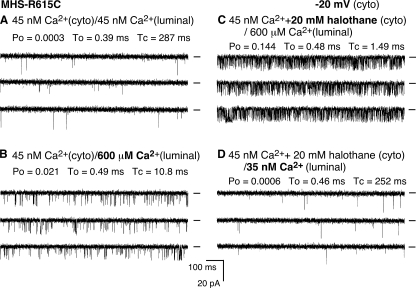

Halothane Potentiates the Luminal Ca2+ Response of Single RyR1 Channels—The effect of halothane on the luminal Ca2+ activation of single RyR1 channels was also investigated (Fig. 2). A single R615C mutant channel exhibited little activity in the presence of 45 nm cytosolic and luminal Ca2+ (Fig. 2A). The addition of 600 μm luminal Ca2+ slightly activated the channel (Fig. 2B). A subsequent addition of 20 mm halothane to the cytosolic side of the channel markedly increased the channel activity (Fig. 2C). The average Po after the addition of halothane was 0.176 ± 0.049 (n = 6) in the presence of 600 μm luminal Ca2+, which was significantly greater than that before the addition of halothane (0.030 ± 0.004) (n = 6) (p < 0.03). It should be noted that halothane has been shown to have little effect on the apparent affinity of EGTA for Ca2+ (32). Importantly, this halothane-induced enhancement was dependent on the presence of luminal Ca2+. Reducing the luminal Ca2+ from 600 μm to ∼35 nm decreased the channel activity to the basal level (Fig. 2D). Similarly, halothane also activated single RyR1 wt channels in a luminal Ca2+-dependent manner (not shown). It should be noted that because of its highly volatile nature, the actual concentration of halothane in the bilayer recording solution would be much lower than that added to the chamber. Nevertheless, these data indicate that at low cytosolic Ca2+, halothane potentiates the response of RyR1 to luminal Ca2+.

FIGURE 2.

Halothane potentiates the response of RyR1 to luminal Ca2+. Single channel activities of the R615C mutant were recorded as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The Ca2+ concentration on both the cytosolic and luminal sides of the channel was adjusted to ∼45 nm (A). The luminal Ca2+ concentration was then increased to 600 μm (B). C, single channel current traces after the addition of halothane to the cytosolic side of the channel. The luminal Ca2+ concentration was then reduced to ∼35 nm in the continued presence of halothane (D). The holding potential was –20 mV, and the openings are downward.

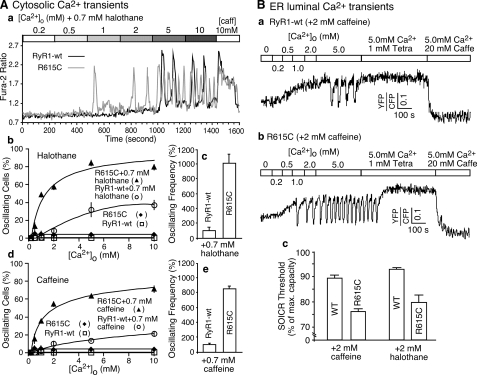

Halothane and the R615C Mutation Enhance the Propensity for SOICR in HEK293 Cells—It has long been demonstrated that halothane induces spontaneous contracture in MHS muscle, but not in normal muscle in an external Ca2+-dependent manner (33), and that the halothane-induced spontaneous SR Ca2+ release is dependent on the SR Ca2+ load (34). To determine whether halothane and the R615C mutation also augment RyR1-mediated spontaneous Ca2+ release or SOICR in a nonmuscle environment, we generated stable, inducible HEK293 cell lines expressing wt or R615C. We have previously shown that elevated [Ca2+]o induces SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing RyR2 (26, 27). Unlike RyR2-expressing cells, cells expressing RyR1 wt or the R615C mutant did not show SOICR in response to elevated [Ca2+]o in the absence of stimuli (Fig. 3A, panel b). However, in the presence of low concentrations of halothane, elevated [Ca2+]o triggered SOICR in both RyR1 wt- and R615C mutant-expressing HEK293 cells (Fig. 3A, panels a and b). Analyzing a number of oscillating cells revealed that HEK293 cells expressing R615C displayed a greater propensity for SOICR than cells expressing wt (Fig. 3A, panel b). The frequency of Ca2+ oscillations in cells expressing the R615C mutant was also much higher than that in cells expressing wt (Fig. 3A, panel c). Similar results were obtained when halothane was replaced with caffeine (Fig. 3A, panels d and e). The parental HEK293 cells do not express a detectable level of RyRs (26, 35). These observations indicate that the MH R615C mutation, halothane, and caffeine can enhance the propensity for SOICR in a nonmuscle environment, suggesting that the response of RyR1 to Ca2+ overload is a major determinant of halothane- or caffeine-induced spontaneous Ca2+ release.

FIGURE 3.

Halothane and the MH R615C mutation increase the propensity for SOICR. A, stable, inducible HEK293 cells expressing RyR1 wt and the R615C mutant were induced with tetracycline for ∼24 h and loaded with 5 μm fura-2 AM in KRH buffer for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were continuously perfused with KRH buffer containing various concentrations of external Ca2+ (0.2–10 mm) and caffeine. Panel a shows single cell fluorescent Ca2+ images of cells expressing RyR1 wt (top panels) and the R615C mutant (bottom panels) in the presence of 0.7 mm halothane at various [Ca2+]o. Fura-2 ratios of representative RyR1 wt (green trace) and the R615C mutant (red trace) cells are shown in panel b. The fraction (%, means ± S.E.) of cells displaying Ca2+ oscillations in the presence or absence of 0.7 mm halothane (panel c) or 0.7 mm caffeine (panel d) is shown. The total numbers of RyR1 wt cells analyzed for Ca2+ oscillations were 320 (without halothane or caffeine), 465 (with 0.7 mm halothane), and 305 (with 0.7 mm caffeine). The total numbers of R615C cells analyzed for Ca2+ oscillations were 290 (without halothane or caffeine), 714 (with 0.7 mm halothane), and 339 (with 0.7 mm caffeine). Panels c and e show the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations at 2 mm [Ca2+]o, in the presence of 0.7 mm halothane and 0.7 mm caffeine, respectively. The values were normalized to the wt level (100%). The data shown are the means ± S.E. from three to five separate experiments. B, the R615C mutation decreases the threshold for SOICR. HEK293 cells expressing wt or R615C were transfected with D1ER cDNA ∼48 h before imaging, and RyR1 expression was induced ∼24 h before imaging. The cells were perfused with KRH buffer containing 2 mm caffeine or 2 mm halothane with various [Ca2+]o, 1 mm tetracaine, or 20 mm caffeine. Representative FRET traces from HEK293 cells expressing either wt (panel a) or R615C (panel b) are shown. The SOICR threshold in cells expressing wt or R615C in the presence of caffeine or halothane is shown in panel c. The threshold for SOICR was determined by calculating the peak luminal Ca2+ level during oscillations as the percentage of the maximum luminal Ca2+ store capacity. The maximum luminal Ca2+ store capacity was estimated by calculating the difference between the maximum luminal Ca2+ level in the presence of tetracaine (1 mm) and the minimum luminal Ca2+ level in the presence of caffeine (20 mm). The data shown are means ± S.E. from two to five separate experiments.

The R615C Mutation Reduces the Luminal Ca2+ Threshold at Which SOICR Occurs—To directly measure the luminal Ca2+ threshold at which SOICR occurs, we used a FRET-based endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ sensor protein, D1ER (31), to monitor the ER luminal Ca2+ dynamics during store Ca2+ overload in HEK293 cells expressing RyR1 wt or R615C. As shown in Fig. 3B (panels a and b), elevated [Ca2+]o increased the level of ER luminal Ca2+. When the luminal Ca2+ reached a threshold level, SOICR occurred, displaying as downward deflections in the FRET signal. SOICR was then suppressed by 1.0 mm tetracaine, an inhibitor of RyR1, to estimate the maximum luminal Ca2+ level. Caffeine (20 mm), an activator of RyR1, was then used to estimate the minimum luminal Ca2+ level by emptying the store. Fig. 3B (panel c) shows that the luminal Ca2+ threshold (percentage of maximum luminal Ca2+ store capacity) at which SOICR occurs is significantly lower in cells expressing R615C (76.1 ± 0.8%, n = 243) than in cells expressing wt (89.5 ± 1.0%, n = 106) (p < 0.00001) in the presence of 2 mm caffeine. There was no significant difference in the maximum luminal Ca2+ store capacity between the R615C-expressing cells (105.5 ± 6.2%) and the wt-expressing cells (100%) (p = 0.25), which was calculated by subtracting the minimum FRET signal (in the presence of 20 mm caffeine) from the maximum FRET signal (in the presence of 1 mm tetracaine). Similarly, the luminal Ca2+ threshold at which SOICR occurs is significantly lower in cells expressing R615C (80.0 ± 3.1%, n = 107) than in cells expressing wt (93.2 ± 0.8%, n = 108) (p < 0.00001) in the presence of 2 mm halothane. The resting luminal Ca2+ level in the presence of near 0 mm external Ca2+ and 2 mm caffeine is also lower in cells expressing R615C (34.0 ± 2.9%) than in cells expressing wt (54.5 ± 4.5%) (p < 0.00001). Similarly, the resting luminal Ca2+ level in the presence of near 0 mm external Ca2+ and 2 mm halothane is lower in cells expressing R615C (62.8 ± 3.3%) than in cells expressing wt (81.5 ± 2.4%) (p < 0.00001). Taken together, these data are consistent with those of single channel studies showing that the R615C mutation and halothane enhance the response of RyR1 to luminal Ca2+, leading to a reduced SOICR threshold and resting ER Ca2+ level.

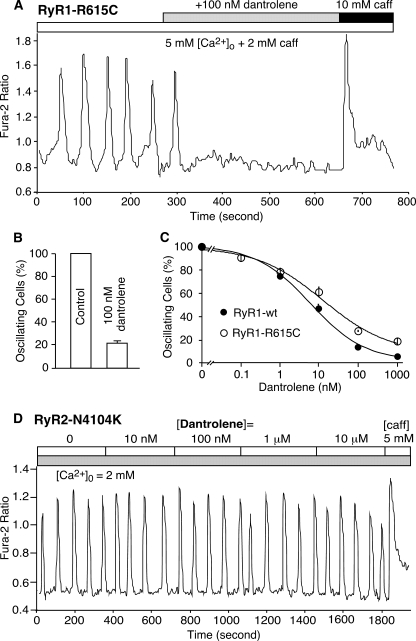

Dantrolene Abolishes SOICR in HEK293 Cells Expressing RyR1-R615C but Not in Cells Expressing RyR2-N4104K—It has also long been shown that dantrolene suppresses caffeine- or halothane-induced spontaneous contracture in MHS muscle (36, 37) and that dantrolene inhibits spontaneous Ca2+ release from skeletal muscle SR but not from cardiac muscle SR (38). To determine whether dantrolene can also suppress caffeine-induced spontaneous Ca2+ release in a nonmuscle environment, we assessed the impact of dantrolene on SOICR in HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 4, HEK293 cells expressing the RyR1-R615C mutant exhibited Ca2+ oscillations in the presence of 5 mm [Ca2+]o plus 2.0 mm caffeine. The addition of 100 nm dantrolene diminished these oscillations, reducing the number of oscillating cells by ∼80% (Fig. 4, A and B). Fig. 4C shows that dantrolene suppressed SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing either the R615C mutant or RyR1 wt with an IC50 of ∼10–20 nm. Interestingly and in contrast, dantrolene did not abolish Ca2+ oscillations in HEK293 cells expressing the disease-causing RyR2 mutation, N4104K, even at high concentrations (10 μm) (Fig. 4D). These data demonstrate that dantrolene potently suppresses RyR1-mediated, but not RyR2-mediated, SOICR in HEK293 cells and therefore suggest that the inhibition of RyR1-mediated SOICR may represent a primary therapeutic action of dantrolene.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of dantrolene on SOICR. Stable, inducible HEK293 cells expressing the RyR1-R615C mutant were loaded with fura-2 AM and perfused with KRH buffer containing 5 mm [Ca2+]o plus 2 mm caffeine in the absence or the presence of 100 nm dantrolene (A). The fraction (%, means ± S.E.) of cells that displayed Ca2+ oscillations before (control) and after the addition of 100 nm dantrolene is shown in B. The dose dependence of dantrolene inhibition of SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing R615C (open circles) or expressing RyR1 wt (solid circles) is shown in C. The total numbers of cells analyzed were 706 in B and 366 for RyR1 wt and 260 for R615C in C from five to eight separate experiments. D shows the effect of dantrolene on SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing the disease-linked RyR2 mutant, N4104K. The cells were perfused with 2 mm [Ca2+]o in the presence of 10 nm to 10 μm dantrolene (D). Similar results were obtained from four separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

Investigations over the past decades have greatly advanced our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms of MH. However, some fundamental questions still remain, including: 1) what intrinsic properties of the RyR1 channel altered by mutations are principally responsible for MH pathogenesis? 2) how do volatile anesthetics trigger MH? and 3) how does dantrolene suppress MH? In the present study, we demonstrated that both the MH R615C mutation and MH-triggering agent, halothane, sensitize the RyR1 channel to activation by luminal Ca2+ and reduce the threshold for SOICR. In contrast, dantrolene, an effective treatment for MH, suppresses SOICR. Based on these observations, we propose that volatile anesthetics, by further reducing the already reduced threshold for SOICR in the MHS muscle, trigger spontaneous Ca2+ release and thus MH, whereas dantrolene suppresses spontaneous Ca2+ release and MH by increasing the SOICR threshold.

The MH R615C Mutation Sensitizes the RyR1 Channel to Luminal Ca2+ Activation—Despite the consistent observation that the MHS pig RyR1 channel is more active than the normal RyR1 channel upon stimulation, many studies have failed to detect major changes in the intrinsic sensitivity of the MHS RyR1 channel to cytosolic Ca2+ activation (1, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20). Consistent with these previous observations, we observed little effect of the MH R615C mutation on the cytosolic Ca2+ dependence of single RyR1 channels (Fig. 1B). How then do the MHS and normal RyR1 channels with similar intrinsic sensitivities to cytosolic Ca2+ activation respond so differently to activation by various stimuli? Given the importance of luminal Ca2+ in regulating SR Ca2+ release, we reasoned that MH mutations may alter the response of the RyR1 channel to luminal Ca2+. To address this possibility, in the present study, we directly assessed the impact of the MH R615C mutation on the sensitivity of single RyR1 channels to luminal Ca2+ activation. We found that the MH R615C mutation markedly enhanced the luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1 (Fig. 1A) and that halothane potentiated this response (Fig. 2). These results therefore suggest that an enhanced sensitivity of the RyR1 channel to luminal Ca2+ may be a primary defect resulting from the R615C mutation and contribute to the observed enhanced activity.

It remains, however, to be determined how the R615C mutation, which is located in the cytoplasmic domain of the channel, affects luminal Ca2+ activation. It has been proposed that the MH R615C mutation weakens the interactions between the N-terminal and the central domains and consequently destabilizes the closed state of the channel (20). It is possible that these domain-domain interactions are involved in the activation of the channel by luminal Ca2+ and that weakening these interactions facilitates luminal Ca2+ activation.

The R615C Mutation and Halothane Reduce the Threshold for SOICR—Because SOICR is triggered by the luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR, an enhanced luminal Ca2+ response would lead to an increased propensity for SOICR. In line with this, we found that halothane and caffeine enhanced SOICR in HEK293 cells expressing the RyR1 wt or the R615C mutant (Fig. 3A) and that HEK293 cells expressing the R615C mutant displayed a reduced threshold for SOICR compared with cells expressing RyR1 wt (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these observations, a number of human MH RyR1 mutations have also been shown to increase the incidence of spontaneous Ca2+ release when expressed in dyspedic myotubes (39). Hence, an enhanced propensity for SOICR may be a common defect of MH RyR1 mutations.

Our observations are also consistent with the results of early studies of the MHS and normal pig skeletal muscles. Nelson et al. (33) demonstrated that halothane induced spontaneous contracture in MHS muscle, but not in normal muscle, and that this halothane-induced contracture is dependent on the external Ca2+ concentration. Nelson et al. (13, 24, 25) also showed that the threshold amount of SR Ca2+ load required for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release to occur in MHS pig SR vesicles was lower than that in normal pig SR and that halothane lowered this threshold. These observations have led to the proposal that a defect in some intraluminal regulatory site for Ca2+ release may underlie MH. Notably, these observations preceded the cloning of the RyR1 cDNA and the identification of the porcine MH mutation R615C. Similarly, Ohnishi et al. (34) demonstrated that the SR Ca2+ content required for halothane-induced Ca2+ release in MHS pig SR was also lower than that in normal SR. Interestingly, when the SR Ca2+ load was below the threshold level, halothane was unable to induce Ca2+ release from either normal or MHS SR vesicles (34). Consistent with these observations, we found that the activation of single RyR1 channels by halothane was also dependent on luminal Ca2+ (Fig. 2) and that halothane and caffeine increased the propensity for SOICR. Taken together, the results of our single channel and SOICR studies and those of previous SR Ca2+ release studies suggest that a reduced threshold for SOICR as a result of enhanced luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1 underlies a causal mechanism of MH.

Suppression of SOICR Is a Primary Action of Dantrolene—Dantrolene, an effective treatment for MH, markedly suppresses spontaneous muscle contracture and SR Ca2+ release (36, 37). Despite its remarkable impact on MH, dantrolene up to ∼50 μm only partially inhibits voltage- or Ca2+-induced SR Ca2+ release, suggesting that the primary action of dantrolene is unlikely to lie in the suppression of voltage- or Ca2+-induced SR Ca2+ release (40–42). On the other hand, if enhanced SOICR activity caused by a reduced SOICR threshold is the cause of MH, one would expect that dantrolene at clinically relevant concentrations (1–10 μm) would be able to diminish RyR1-mediated SOICR activity even in a nonmuscle environment. Indeed, we found that dantrolene inhibited SOICR in HEK293 nonmuscle cells expressing the R615C mutant with an IC50 of ∼20 nm (Fig. 4). Similarly, Zhang et al. (43) have recently shown that azumolene, a dantrolene analog, decreased the frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in skeletal muscle fibers with an IC50 of ∼250 nm. The fact that much lower concentrations of dantrolene are required for suppressing RyR1-mediated SOICR compared with those required for inhibiting voltage-triggered SR Ca2+ release suggests that the suppression of RyR1-mediated SOICR may be a primary action of dantrolene.

Whether direct and specific binding of dantrolene to the RyR1 channel fully accounts for its therapeutic actions as a skeletal muscle relaxant and antidote for MH remains an open question (44–46). In this regard, we were unable to detect significant effects of dantrolene on either the cytosolic or luminal Ca2+ activation of single RyR1 channels incorporated into lipid bilayers (not shown), despite the marked effects of dantrolene on RyR1-mediated SOICR that we observed. The reasons for this apparent discrepancy are unknown. It has been shown that dantrolene binds to the N-terminal region of RyR1 and stabilizes domain-domain interactions, indicating that RyR1 or its complex is a direct target of dantrolene (47, 48). However, the functional manifestation of dantrolene binding to RyR1 may require the presence of other factors such as calmodulin, ATP, or other RyR1-associated proteins (41, 42). Importantly, we found that dantrolene did not affect SOICR in cells expressing a mutant RyR2 channel (Fig. 4). Thus our results convincingly demonstrate that dantrolene suppression of SOICR is strictly dependent on the expression of the RyR1 isoform. It has recently been shown that RyR1 is associated with components of the store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway and that azumolene suppresses the store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway that is coupled to RyR1 (49, 50). It is therefore possible that the interaction between RyR1 and components of store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway or other unknown RyR1-associated proteins is required for the action of dantrolene. Clearly, further studies are needed to understand the molecular mechanism by which dantrolene suppresses SOICR.

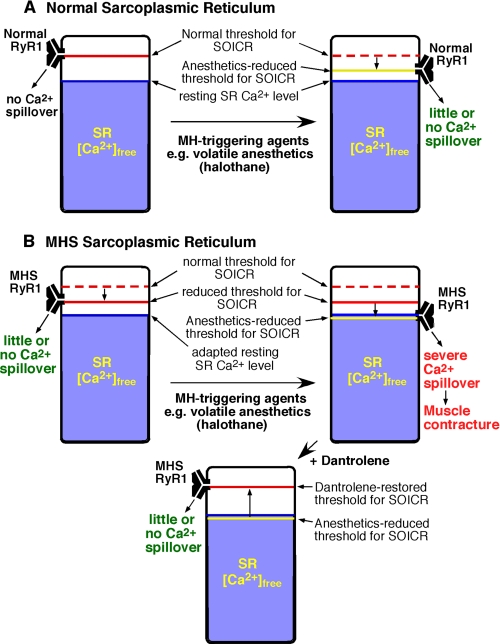

A New View of MH—Our results support a model in which the MH R615C mutation and the MH-triggering agent halothane reduce the threshold for luminal Ca2+ activation of RyR1 and thus the threshold for SOICR, whereas the MH-suppressing agent, dantrolene, inhibits SOICR (Fig. 5). In this view, the threshold for SOICR from normal SR is higher than the SR-free Ca2+ level under both resting and stimulated conditions (Fig. 5A). Therefore, there is little or no Ca2+ spillover from normal SR. On the other hand, in the MHS SR, the threshold for SOICR is reduced because of mutations in RyR1 (Fig. 5B). Under resting conditions, the reduced threshold for mutant channels remains higher than the resting SR-free Ca2+ level, so that there is again little or no Ca2+ spillover. However, in the presence of MH-triggering agents (e.g. halothane), the threshold is further reduced, and SOICR is more likely to occur. The resulting SR Ca2+ spillover leads to spontaneous muscle contraction and MH. Dantrolene reverses the effect of the MH mutations and of volatile anesthetics by increasing the SOICR threshold.

FIGURE 5.

A proposed model for the action of the porcine MH mutation, the MH-triggering agent, halothane, and the MH-suppressing agent, dantrolene. The threshold for SOICR and the SR-free Ca2+ level in normal (A) and the MHS SR (B) in the resting and stimulated states are schematically shown. The SOICR threshold, which is reduced in the MHS SR as a consequence of the R615C RyR1 mutation (short arrow), is depicted by a red bar. The SR-free Ca2+ level is represented by the blue area. The anesthetic-reduced SOICR threshold is depicted by a yellow bar. When the SOICR threshold decreases to the SR-free Ca2+ level, SOICR occurs, leading to a large SR Ca2+ spillover, which can trigger spontaneous Ca2+ release, muscle contraction, and MH. Dantrolene restores the reduced SOICR threshold.

In this working model, SR Ca2+ handling in MHS muscles at rest is expected to be normal, if the reduced SOICR threshold would still be significantly higher than the resting SR-free Ca2+ level. Consistent with this prediction, the majority of MHS individuals are asymptomatic in the absence of triggering agents. However, if the reduced SOICR threshold were too close to the resting SR Ca2+ level because of more severe RyR1 mutations, Ca2+ spillover could occur even under the resting conditions. Such uncontrolled SR Ca2+ release at rest may account for the muscle defects seen in those MHS individuals with central core disease (1–5).

Implication for Stress-induced MH—In addition to volatile anesthetics, physical and emotional stress can also trigger MH in pigs and humans, but the mechanism underlying stress-induced MH is unclear. It is well known that in the heart, physical and emotional stress activates the β-adrenergic receptor/cAMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase signaling pathway, leading to an increase in the SR Ca2+ load and SR Ca2+ release (51). Rudolf et al. (52) have recently demonstrated directly that, as in cardiac muscle, β-adrenergic receptor stimulation also increases the SR Ca2+ load and Ca2+ release in skeletal muscle. Because the occurrence of SOICR is determined not only by its threshold but also by the SR Ca2+ load (Fig. 5), physical and emotional stress may induce SOICR by increasing the SR Ca2+ load. Because the threshold for SOICR is reduced in the MHS SR, SOICR and thus spontaneous muscle contraction would be more likely to occur in MHS pigs or individuals during stress-induced SR Ca2+ overload. Therefore, conditions that affect either the SOICR threshold or SR Ca2+ loading will have a profound impact on the occurrence of SOICR and thus the susceptibility to MH. This multi-factorial dependence of the occurrence of SOICR may provide an explanation for the unsolved heterogeneity of MH expression in MHS individuals carrying even the same RyR1 mutation.

Conclusions—In summary, the present study sheds novel insight into the causal mechanism of MH and proposes a unifying model for MH susceptibility, MH triggering, and MH suppression. We have demonstrated that both the MH R615C mutation and the MH trigger halothane act to reduce the threshold for luminal Ca2+ activation and SOICR, whereas the MH antidote dantrolene suppresses SOICR. Together these data suggest that the sensitivity of the RyR1 channel to luminal Ca2+ activation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of MH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jonathan Lytton for the use of his single cell Ca2+ imaging facility and Jeff Bolstad for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 1RO1HL75210 and RO1HL076433. This work was also supported by funds from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to S. R. W. C.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MH, malignant hyperthermia; MHS, MH-susceptible; SOICR, store overload-induced Ca2+ release; wt, wild type; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; AM, acetoxymethyl ester; KRH, Krebs-Ringer-Hepes; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

References

- 1.Mickelson, J. R., and Louis, C. F. (1996) Physiol. Rev. 76 537–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loke, J., and MacLennan, D. H. (1998) Am. J. Med. 104 470–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy, T. V., Quane, K. A., and Lynch, P. J. (2000) Hum. Mutat. 15 410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyfenko, A. D., Goonasekera, S. A., and Dirksen, R. T. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 322 1256–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Treves, S., Anderson, A. A., Ducreux, S., Divet, A., Bleunven, C., Grasso, C., Paesante, S., and Zorzato, F. (2005) Neuromuscul. Disord. 15 577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii, J., Otsu, K., Zorzato, F., de Leon, S., Khanna, V. K., Weiler, J. E., O'Brien, P. J., and MacLennan, D. H. (1991) Science 253 448–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacLennan, D. H., and Phillips, M. S. (1992) Science 256 789–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson, R., Carpenter, D., Shaw, M., Halsall, J., and Hopkins, P. (2006) Hum. Mutat. 27 977–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otsu, K., Nishida, K., Kimura, Y., Kuzuya, T., Hori, M., Kamada, T., and Tada, M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 9413–9415 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treves, S., Larini, F., Menegazzi, P., Steinberg, T. H., Koval, M., Vilsen, B., Andersen, J. P., and Zorzato, F. (1994) Biochem. J. 301 661–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong, J., Oyamada, H., Demaurex, N., Grinstein, S., McCarthy, T. V., and MacLennan, D. H. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 26332–26339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dietze, B., Henke, J., Eichinger, H. M., Lehmann-Horn, F., and Melzer, W. (2000) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 526 507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson, T. E. (2002) Curr. Mol. Med. 2 347–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang, T., Ta, T. A., Pessah, I. N., and Allen, P. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 25722–25730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fill, M., Coronado, R., Mickelson, J. R., Vilven, J., Ma, J. J., Jacobson, B. A., and Louis, C. F. (1990) Biophys. J. 57 471–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shomer, N. H., Louis, C. F., Fill, M., Litterer, L. A., and Mickelson, J. R. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 264 C125–C135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laver, D. R., Owen, V. J., Junankar, P. R., Taske, N. L., Dulhunty, A. F., and Lamb, G. D. (1997) Biophys. J. 73 1913–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen, V. J., Taske, N. L., and Lamb, G. D. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. 272 C203–C211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balog, E. M., Fruen, B. R., Shomer, N. H., and Louis, C. F. (2001) Biophys. J. 81 2050–2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murayama, T., Oba, T., Hara, H., Wakebe, K., Ikemoto, N., and Ogawa, Y. (2007) Biochem. J. 402 349–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripathy, A., and Meissner, G. (1996) Biophys. J. 70 2600–2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sitsapesan, R., and Williams, A. J. (1997) J. Membr. Biol. 159 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gyorke, S., and Terentyev, D. (2008) Cardiovasc. Res. 77 245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson, T. E. (1983) J. Clin. Investig. 72 862–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson, T., Lin, M., and Volpe, P. (1991) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 256 645–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang, D., Xiao, B., Yang, D., Wang, R., Choi, P., Zhang, L., Cheng, H., and Chen, S. R. W. (2004) 101 13062–13067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Jiang, D., Wang, R., Xiao, B., Kong, H., Hunt, D. J., Choi, P., Zhang, L., and Chen, S. R. W. (2005) Circ. Res. 97 1173–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priori, S. G., and Napolitano, C. (2005) J. Clin. Investig. 115 2033–2038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho, S. N., Hunt, H. D., Horton, R. M., Pullen, J. K., and Pease, L. R. (1989) Gene (Amst.) 77 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabiato, A., and Fabiato, F. (1979) J. Physiol. (Paris) 75 463–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer, A. E., Jin, C., Reed, J. C., and Tsien, R. Y. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 17404–17409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Housmans, P. R., and Wanek, L. A. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 284 60–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson, T. E., Bedell, D. M., and Jones, E. W. (1975) Anesthesiology 42 301–306 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohnishi, S. T., Taylor, S., and Gronert, G. A. (1983) FEBS Lett. 161 103–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong, J., Du, G. G., Chen, S. R., and MacLennan, D. H. (1999) Biochem. J. 343 39–44 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okumura, F., Crocker, B. D., and Denborough, M. A. (1980) Br. J. Anaesth. 52 377–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster, P. S., and Denborough, M. A. (1989) Br. J. Anaesth. 62 566–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Winkle, W. B. (1976) Science 193 1130–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dirksen, R. T., and Avila, G. (2004) Biophys. J. 87 3193–3204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hainaut, K., and Desmedt, J. (1974) Nature 252 728–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fruen, B. R., Mickelson, J. R., and Louis, C. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 26965–26971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Louis, C., Balog, E., and Fruen, B. (2001) Biosci. Rep. 21 155–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, Y., Rodney, G. G., and Schneider, M. F. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314 94–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson, T., Lin, M., Zapata-Sudo, G., and Sudo, R. (1996) Anesthesiology 84 1368–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szentesi, P., Collet, C., Sarkozi, S., Szegedi, C., Jona, I., Jacquemond, V., Kovacs, L., and Csernoch, L. (2001) J. Gen. Physiol. 118 355–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cherednichenko, G., Ward, C. W., Feng, W., Cabrales, E., Michaelson, L., Samso, M., Lopez, J. R., Allen, P. D., and Pessah, I. N. (2008) Mol. Pharmacol. 73 1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paul-Pletzer, K., Yamamoto, T., Bhat, M. B., Ma, J., Ikemoto, N., Jimenez, L. S., Morimoto, H., Williams, P. G., and Parness, J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 34918–34923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi, S., Bannister, M. L., Gangopadhyay, J. P., Hamada, T., Parness, J., and Ikemoto, N. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 6580–6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sampieri, A., Diaz-Munoz, M., Antaramian, A., and Vaca, L. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 24804–24815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao, X., Weisleder, N., Han, X., Pan, Z., Parness, J., Brotto, M., and Ma, J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 33477–33486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bers, D. M. (2002) Nature 415 198–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rudolf, R., Magalhaes, P. J., and Pozzan, T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 173 187–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]