Abstract

We report the integration of the linkage map of tomato chromosome 2 with a high-density bacterial artificial chromosome fluorescence in situ hybridization (BAC–FISH)-based cytogenetic map. The euchromatic block of chromosome 2 resides between 13 and 142 cM and has a physical length of 48.12 μm, with 1 μm equivalent to 540 kb. BAC–FISH resolved a pair of loci that were 3.7–3.9 Mb apart and were not resolved on the linkage map. Most of the regions had crossover densities close to the mean of ∼200 kb/cM. Relatively hot and cold spots of recombination were unevenly distributed along the chromosome. The distribution of centimorgan/micrometer values was similar to the previously reported recombination nodule distribution along the pachytene chromosome. FISH-based physical maps will play an important role in advanced genomics research for tomato, including map-based cloning of agronomically important traits and whole-genome sequencing.

ECONOMICALLY, the Solanaceae compose the third most important plant taxon, and consist of >3000 species. Distinctive aspects of development and the variety of phenotypes and habitats make the Solanaceae good models for investigation of the genetic bases of diversification and adaptation. To this end, the “International Solanaceae Genome Project (SOL)” was launched (Mueller et al. 2005). Tomato is well suited to represent the Solanaceae because it has a relatively small genome and a strong genetics, genomics, and cytogenetics foundation.

Peterson et al. (1999) provided an overview of the DNA content and physical length of all 24 chromosome arms. Tomato has pericentromeric heterochromatin, as do other Solanaceae. The synaptonemal complex karyotype data indicate that 77% of the tomato genome is located in heterochromatin and 23% in euchromatin (Peterson et al. 1996). The genome size (1C) is ∼95 pg of DNA (Michaelson et al. 1991), implying 212 Mb of euchromatin (Bennett and Smith 1976; http://www.sgn.cornell.edu; tomato sequencing scope and completion criteria).

Excellent morphological and molecular genetic maps of the tomato genome are available (Rick and Yoder 1988; Tanksley et al. 1992). For example, >1000 restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs), mutants, and isozymes have been located on a map that totals >1276 cM (Tanksley et al. 1992). In addition, 67 RFLP and 1175 amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers were used to construct a RFLP–AFLP map that totals 1482 cM (Haanstra et al. 1999). To date, 2037 markers have been used to create a map that totals 1460 cM; this map is available from the Solanaceae Genome Network (SGN) database (http://www.sgn.cornell.edu; EXPEN 2000 map) and is used for the “SOL” project. This linkage map, which represents all the chromosomes, does not provide sufficient detail to support genome sequencing. Because linkage map distances are not simply related to physical distances, physical mapping is needed to determine the locations of markers on chromosomes. For this purpose, bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) fingerprinting and overgo hybridization have been applied. Currently, 3439 contigs have been anchored on the EXPEN 2000 map.

As participants in the international SOL consortium, we are responsible for sequencing the euchromatic region of chromosome 2, the third largest chromosome of tomato (Sherman and Stack 1992). Critical steps in this process are identification of the boundaries of the euchromatin and determination of the physical locations of markers. Pachytene chromosome analysis indicates that the physical size of the euchromatin is 22–26 Mb (Peterson et al. 1996; Chang 2004). The characteristic morphology of chromosome 2, with its nucleolar organizing region (NOR) and acrocentric structure, makes it easily distinguishable from the other chromosomes. Furthermore, the entire euchromatic block is located on the distal region of the long arm of the chromosome and is clearly separated from the pericentromeric heterochromatin. The linkage map of chromosome 2 has been well defined using 308 molecular markers, and its size is estimated as 143 cM (EXPEN 2000 map). A physical map has also been constructed for chromosome 2 using 75 marker-anchored BAC clones (EXPEN 2000 map). However, neither map provides sufficient detail of the physical locations of markers to initiate genome sequencing. “Molecular cytogenetics” can contribute significantly to the genome map by resolving the order of closely linked markers and confirming the physical positions of markers on the linkage groups (Anderson et al. 2004; Van Der Knaap et al. 2004; Chang et al. 2007).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is the most versatile and accurate method for determining the euchromatic–heterochromatic boundaries, the locations of chromosome-specific BAC clones, and the locations of repetitive and single-copy DNA sequences (Fransz et al. 2000; Cheng et al. 2001a,b; Wang et al. 2006). Here, we report the cytological and physical structure of tomato chromosome 2 in relation to the linkage map, using BAC–FISH mapping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material:

Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum cv. Micro-Tom) plants were grown in a controlled-environment room at 26° ± 1° under 16 hr light/8 hr dark.

BAC probe preparations:

All BAC clones used for BAC–FISH were kindly provided by S. Tanksley and J. Giovannoni at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York. Tomato BAC probes were labeled with digoxigenin-11-dUTP or biotin-16-dUTP by nick translation according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer of the labeling kits (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The Arabidopsis pAtT4 clone (Richards and Ausubel 1988) and the wheat pTa71 clone containing a 9.1-kb fragment of 45S rDNA (Gerlach and Bedrock 1979) were used to detect telomeric and rDNA regions, respectively.

Chromosome preparation:

Pollen mother cells (PMCs) were separated using the method of Fransz et al. (2000) with some modification. Immature flower buds were fixed in ethanol:acetic acid (3:1) for 2 hr and stored at 4°. These were rinsed in distilled water and incubated in an enzyme mix (0.3% pectolyase, 0.3% cytohelicase, and 0.3% cellulase) in citrate buffer (10 mm sodium citrate, pH 4.5) for 2 hr. Each bud was softened in 60% acetic acid on an uncoated, ethanol-cleaned microscopic slide kept at 45° on a hot plate. The contents were smeared on the slide, fixed with ice-cold ethanol:acetic acid (3:1), and dried.

FISH:

The FISH procedure was previously reported by Koo et al. (2004). In brief, chromosomal DNA on the slides was denatured with 70% formamide at 70° for 2.5 min, followed by dehydration in a 70, 85, 95, and 100% ethanol series at −20° for 3 min each. The probe mixture containing 50% formamide (v/v), 10% dextran sulfate (w/v), 5 ng/μl salmon sperm DNA, and 50 ng/μl labeled probe DNA was heated at 90° for 10 min and then kept on ice for 5 min. A 20-μl aliquot of this mixture was applied to the denatured chromosomal DNA and covered with a glass coverslip. The slides were then placed in a humid chamber at 37° for 18 hr. Probes were detected with avidin–FITC and anti-digoxigenin Cy3 (Roche). Chromosomes were counterstained with 1 μg/μl 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma, St. Louis). The signals were detected using a cooled CCD camera (CoolSNAP; Photometrics, Tokyo). The images were obtained with a Leica epi-fluorescence microscope equipped with FITC–DAPI two-way or FITC–rhodamine–DAPI three-way filter sets (Leica, Tokyo) and were processed with Meta Imaging Series TM 4.6 software. The final printed images were prepared using Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Fiber-FISH:

Leaf nuclei were prepared as described by Jackson et al. (1998). A suspension of nuclei was deposited at one end of a poly-l-lysine-coated slide (Sigma) and air dried for 10 min. STE lysis buffer (8 μl) was added, and the slide was incubated at room temperature for 4 min. A clean coverslip was used to slowly drag the contents along the slide. The preparation was air dried, fixed in ethanol:glacial acetic acid (3:1) for 2 min, and baked at 60° for 30 min. The DNA fiber preparation was incubated with a probe mixture, covered with a 22 × 40-mm coverslip, and sealed with rubber cement. The slide was placed in direct contact with a heated surface in an oven at 80° for 3 min, transferred to a wet chamber that had been prewarmed at 80° for 2 min, and then transferred to 37° for overnight incubation. The posthybridization washing stringency was the same as in FISH of chromosome spreads. Signal detection was performed according to Koo et al. (2004).

Chromosome identification and measurement:

The images of 20 DAPI-stained pachytene bivalents at approximately the same stage were captured from different PMCs to study the distributions of heterochromatin, positions of FISH signals, and lengths of pachytene chromosomes. The images were measured directly on the screen using the FISH Image System (Meta Imaging Series TM 4.6).

RESULTS

Cytological architecture of chromosome 2:

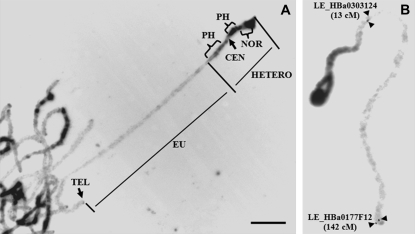

The pachytene chromosome 2 of tomato is easily distinguished from the other chromosomes because it is acrocentric and bears a large secondary structure, the NOR, on the short arm (Peterson et al. 1996). The DAPI staining of the pachytene chromosome demonstrated striking differences between the euchromatin and the heterochromatin. Brightly fluorescing heterochromatic regions were detected next to the centromere of the long arm and over the entire short arm (Figure 1A). Weakly fluorescing euchromatin was observed on the long arm (Figure 1A). Chromosome 2 at meiotic prophase I was a fully paired bivalent with a mean length of 70.22 μm, based on 20 independent measurements. The lengths of the euchromatic and heterochromatic regions (including the NOR) were 48.12 ± 3.17 and 22.1 ± 1.23 μm, respectively. Previous studies estimated the size of the euchromatic region of chromosome 2 as 22–26 Mb (Sherman and Stack 1992; Peterson et al. 1996; Chang 2004). We used the largest size estimation (26 Mb), following guidelines of the International Tomato Genome Sequencing Project. Thus, we considered the euchromatin of the pachytene chromosome to have an average of 540 kb/μm.

Figure 1.—

Cytological architecture of tomato chromosome 2. (A) DAPI-stained pachytene chromosome 2. (B) FISH pattern on pachytene chromosome 2 using probes for both digoxigenin-labeled BAC clone LE_HBa0303I24 and biotin-labeled BAC clone LE_HBa0177F12. DAPI-stained chromosomes and FISH signals were converted to a black-and-white image to enhance the visualization of distribution of euchromatin and heterochromatin on the pachytene chromosome. NOR, nucleolar organizing region; CEN, centromere; PH, pericentromeric heterochromatin; TEL, telomere; EU, euchromatin; HETERO, heterochromatin. Bar, 10 μm.

Determination of the euchromatin borders:

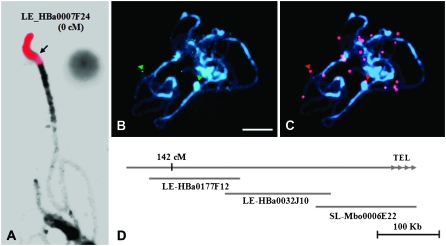

Several BAC probes anchored at each end of linkage group 2 were hybridized to pachytene bivalents, and the physical locations of the BAC–FISH signals were examined. The marker cLER-1-H17 was mapped onto 0.0 cM, which is the north end of linkage group 2. The FISH signal for the BAC clone LE_HBa0007F24 anchored by cLER-1-H17 was detected on the distal end of the short arm of chromosome 2 where it covered the NOR (Figure 2A), and minor signals were also detected on the pericentromeric regions of some pachytene chromosomes (data not shown). The other BAC clones anchored to molecular markers located between 0 and 12 cM gave multiple FISH signals in the pericentromeric heterochromatic regions of all chromosomes (data not shown). The BAC–FISH signal of the T1238 (13 cM)-anchored LE_HBa0303I24 BAC was seen only near the boundary of the euchromatin and pericentromeric heterochromatin. This was located at 3.5 ± 1.3 μm from the pericentromeric heterochromatic region of the long arm (Figure 1B). The south end of the euchromatin was verified by the T1554 (142 cM)-anchored BAC clone LE_HBa0177F12. The FISH signal for LE_HBa0177F12 was detected at the distal end of the long arm of the pachytene chromosome 2 (Figure 1B). Sequencing revealed that SL_MboI0006E22, containing telomere-specific repeated sequences, is located 100 kb from LE-HBa0177F12 (Figure 2, B–D). The biotin-labeled SL_MboI0006E02 (green) was detected at the distal ends of several pachytene chromosomes, including chromosome 2 (Figure 2B). The digoxigenin-labeled Arabidopsis telomere-specific probe (pAtT4, red) was colocalized with green signals generated from SL_MboI0006E02 (Figure 2C). These data taken together identified the euchromatin between 13 and 142 cM as suitable for our study.

Figure 2.—

Physical coverage of the genetic linkage map of tomato chromosome 2. (A) The FISH signal from the BAC clone located at the 0-cM position was detected on the nucleolar organizing region (NOR). Digoxigenin-labeled LE_HBa0007F24 (red) anchored by cLEC-7-P21 (0 cM) was observed at the distal ends of the short arm, which is marked by a 45S rDNA locus. (B) Pachytene chromosomes of tomato were hybridized with biotin-labeled SL_MboI0006E22 (green). Arrowheads indicate pachytene chromosome 2. (C) The pachytene chromosomes in B were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled Arabidopsis pAtT4 containing the telomere-specific sequence. (D) Sequencing results indicate that the telomere-specific repeat sequence containing SL_Mbo0006E22 is 100 kb away from LE_HBa0032J10. Bar, 10 μm.

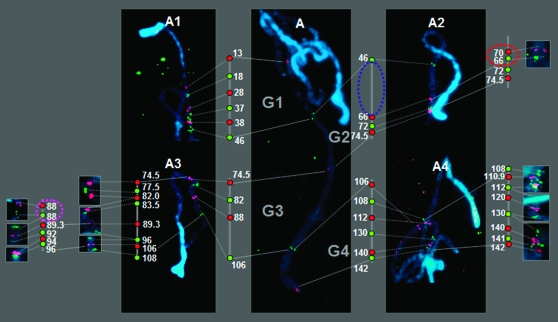

Integration of the cytogenetic and linkage maps:

To construct an integrated high-density cytogenetic map of chromosome 2, we selected 28 BAC clones anchored to molecular markers that were dispersed along the entire linkage group 2 (Table 1). These BAC-derived probes yielded strong FISH signals in pachytene chromosome 2 and clearly demonstrated the corresponding position and order of the selected BAC clones (Figure 3, A1–A4). The order of the selected marker-anchored BAC clones was the same as in the linkage map, except for an inversion of the markers located at 66 and 70 cM (Red dotted circles in Figure 3, A2). In addition to the identification of this inversion, the BAC–FISH map sometimes resolved loci that were not resolved on the linkage map. For example, T1555 and T1535 resided at the same position in the linkage map, but, in the BAC–FISH map, the signals anchored to the two markers were visibly separated (pink dotted circles in Figure 3, A3).

TABLE 1.

List of BAC clones used to integrate the genetic and cytogenetic maps

| Position in linkage group 2 | BAC |

|---|---|

| 13 | LE_HBa0303I24 |

| 18 | LE_HBa0025N15 |

| 28 | LE_HBa0025A22 |

| 37 | LE_HBa0155C04 |

| 38 | LE_HBa0160F05 |

| 46 | LE_HBa0072A04 |

| 66 | LE_HBa0059M17 |

| 70 | SL_MboI0019I01 |

| 72 | LE_HBa0167J21 |

| 74.5 | LE_HBa0320D04 |

| 77.5 | LE_HBa0291P19 |

| 82 | LE_HBa0013N18 |

| 83.5 | LE_HBa0009K06 |

| 88 | LE_HBa0164H08 |

| 88 | LE_HBa0213A01 |

| 89.3 | LE_HBa0134G09 |

| 92 | LE_HBa0016A12 |

| 94 | LE_HBa0011A02 |

| 96 | SL_MboI0014P22 |

| 106 | LE_HBa0172G12 |

| 108 | LE_HBa0046M08 |

| 110.9 | LE_HBa0150M11 |

| 112 | LE_HBa0111M10 |

| 120 | LE_HBa0073P13 |

| 130 | LE_HBa0155D20 |

| 140 | LE_HBa0064B17 |

| 141 | LE_HBa0194L19 |

| 142 | LE_HBa0177F12 |

Figure 3.—

Integration of cytogenetic and genetic maps. (A) Pachytene chromosome hybridized using five biotin- or digoxigenin-labeled BAC clones (LE_HBa0303I24, 13 cM; LE_HBa0072A04, 46 cM; LE-HBa0204D01, 74.5 cM; LE_HBa0172G12, 106 cM; LE_HBa0177F12, 142 cM). G1–G4 represent designated genetic distance blocks of 33, 27, 33, and 36 cM, respectively. (A1–A4) Twenty-eight BAC clones hybridized to pachytene chromosome 2. The green and red dots on each line indicate BAC–FISH results from the left and the right, respectively; the distance is not proportional to the actual distance. The blue dotted circle indicates the physical gap. The red dotted circle indicates the reversed order of loci between the genetic and the cytogenetic maps. The pink dotted circle indicates two separate loci that were colocalized in the genetic map.

Physical gaps in linkage map 2:

The initial selection of marker-anchored BAC clones suggested four gaps (i.e., the absence of molecular marker-anchored BAC regions) that were ≥10 cM long: 18–28 cM, 46–66 cM, 96–106 cM, and 112–130 cM. However, the BAC–FISH analysis demonstrated that the gap that occurred between 46 and 70 cM (note the inversion of loci at 66 and 70 cM) was the only real physical gap (blue dotted circle in Figure 3, A2). The distance between the two FISH signals observed from LE_HBa0072A04 (46 cM) and LE_HBa0329G05 (70 cM) was 7.28 μm (data not shown), implying a physical distance of ∼3.93 Mb (i.e., 7.28 μm × 540 kb/μm). On the basis that 1 cM = 185 kb, the 20-cM interval is estimated to be 3.70 Mb. Thus, the two calculations gave similar physical distances for the large gap on chromosome 2.

Estimation of the base pair/centimorgan relationship:

Molecular marker-anchored BAC–FISH mapping was used to determine the relationship between base pairs and centimorgans (Cheng et al. 2002; Chang et al. 2007). We used five BAC-derived probes for the global determination of the base pair/centimorgan relationship. The five BAC–FISH signals were detected and easily separated into four physical blocks, G1, G2, G3, and G4 (Figure 3, A), according to genetic distances of 33, 27, 33, and 36 cM, respectively. The physical portions of these four blocks composed 24% (G1, 5.8 Mb), 20.9% (G2, 5.1 Mb), 35.3% (G3, 8.5 Mb), and 19.6% (G4, 4.7 Mb) of the entire euchromatic portion of chromosome 2. The base pair/centimorgan relationships calculated from these observations were 176 kb/cM (G1), 189 kb/cM (G2), 258 kb/cM (G3), and 131 kb/cM (G4).

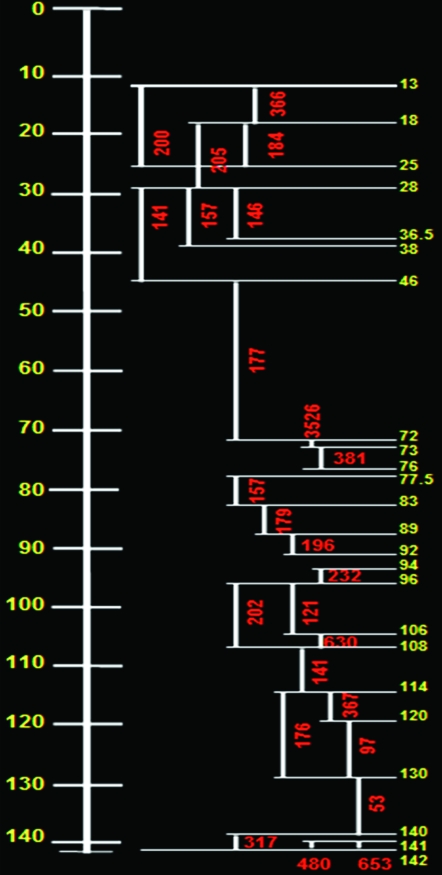

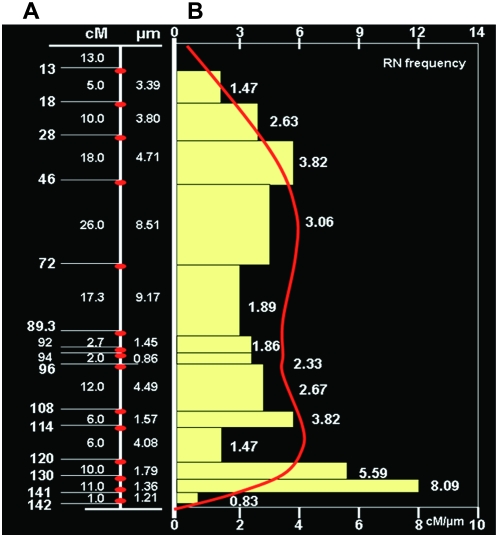

In addition to these rather global measurements of the base pair/centimorgan relationship, we measured more local base pair/centimorgan relationships using 28 BAC clones covering the entire chromosome 2 (Table 2). For most of chromosome 2, the base pair/centimorgan relationship was <200 kb/cM (Figure 4). Some hot spots were detected between 120 and 140 cM, and some cold spots between 72 and 73 cM (Figure 4). Both ends of the euchromatin block have less recombination than the rest of chromosome 2 (Figure 4).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of cytogenetic and genetic distances between loci

| BAC clones (position in genetic map) | Mean distance ± SD (μm) | Linkage distance (cM) | kb/cM | cM/μm | No. of measurements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LE_HBa0303I24(13)–LE_HBa025N15 (18) | 3.39 ± 2.06 | 5 | 366 | 1.5 | 3 |

| LE_HBa0303I24(13)–LE_HBa0209K17 (25) | 4.46 ± 0.48 | 12 | 200 | 2.7 | 3 |

| LE_HBa025N15(18)–LE_HBa0209K17(25) | 2.38 ± 0.49 | 7 | 184 | 2.9 | 6 |

| LE_HBa025N15(18)–LE_HBa0025A22 (28) | 3.8 | 10 | 205 | 2.6 | 1 |

| LE_HBa0025A22(28)–LE_HBa0155C04 (36.5) | 2.31 | 8.5 | 146 | 3.7 | 1 |

| LE_HBa0025A22(28)–LE_HBa0160F05 (38) | 2.91 | 10 | 157 | 3.4 | 1 |

| LE_HBa0025A22(28)–LE_HBa0072A04 (46) | 4.71 | 18 | 141 | 3.8 | 1 |

| LE_HBa0066C13(46)–LE_HBa0167J21 (72) | 8.51 ± 1.16 | 26 | 177 | 3.1 | 6 |

| LE_HBa0167J21(72)–LE_HBa0204D01 (73) | 6.53 ± 5.5 | 1 | 3,526 | 0.1 | 3 |

| SL_MboI0108P14(72)–LE_HBa0204D01 (73) | 21.86 ± 0.44 | 1 | 11,806 | 0.0 | 5 |

| LE_HBa0204D01(73)–LE_HBa0198A03 (76) | 2.11 ± 0.2 | 3 | 381 | 1.4 | 3 |

| LE_HBa0291P19(77.5)–LE_HBa0060J03 (83) | 1.6 ± 0.35 | 5.5 | 157 | 3.4 | 14 |

| LE_HBa0060J03(83)–LE_HBa0164H08 (89) | 1.99 ± 0.27 | 6 | 179 | 3.0 | 6 |

| LE_HBa0164H08(89)–LE_HBa0016A12 (92) | 1.09 ± 0.31 | 3 | 196 | 2.8 | 3 |

| LE_HBa0011A02(94)–SL_MboI1014P22 (96) | 0.86 ± 0.16 | 2 | 232 | 2.3 | 3 |

| SL_MboI1014P22(96)–LE_HBa0172G12 (106) | 2.25 ± 0.52 | 10 | 121 | 4.4 | 15 |

Figure 4.—

Comparison of linkage and physical distances of loci. Left: the tomato genetic linkage map 2; map positions are given in centimorgans (yellow). Right: the physical distance in base pairs (red) corresponding to 1 cM. Horizontal bars represent the analyzed loci (yellow, corresponding to the genetic linkage map 2); vertical bars indicate the regions analyzed using BAC–FISH.

Recombination nodules (RNs) represent real crossovers in the genome and are available for tomato (Sherman and Stack 1995). Therefore, we compared the centimorgan/micrometer relationship with the average number of RNs along chromosome 2. The calculated centimorgan:micrometer ratio trends are similar to the RN distribution redrawn from Sherman and Stack (1995) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.—

Determination of the centimorgan/micrometer relationships. (A) Chromosome diagram with genetic (left) and cytological (right) distances between analyzed loci. Red ellipses indicate the analyzed loci. (B) Comparison of the RN distribution and the centimorgan:micrometer ratio along the length of chromosome 2. The y-axis represents the long arm of chromosome 2. The top x-axis is the number of RNs in 0.1-μm intervals along the chromosome. The bottom x-axis is the centimorgan:micrometer ratio along the chromosome. The red line indicates the general trend in the RN distribution, redrawn from Sherman and Stack (1995). The horizontal bars indicate the ratio of the genetic distance between analyzed loci (values to the left in B) to the cytological distance between the analyzed BACs (values to the right in B). The value of each bar is shown at the right of the bar.

BAC–FISH-identified chromosome 2-specific BAC clones:

Because plant genomes contain many repetitive and redundant sequences, the first task in sequencing the entire euchromatic region of chromosome 2 is the selection of chromosome 2-specific anchored BAC clones. Thus, we first selected all BAC clones anchored to molecular markers located between 13 and 142 cM in linkage group 2. In total, 69 BAC clones were selected from the SGN database (http://www.sgn.cornell.edu). BAC–FISH analyses of these BAC clones demonstrated several different types of hybridization patterns (Table 3): a single FISH signal was located on pachytene chromosome 2 for 37 BACs; multiple FISH signals were located on the pericentromeric heterochromatin regions of the pachytene chromosomes, including chromosome 2, for three BACs; no FISH signal was located on pachytene chromosome 2, but was located on other chromosomes for one BAC; and no FISH signal was observed on any chromosome for 28 BACs. BAC–FISH identified 37 BAC clones that could be used as “seed” BACs for sequencing. This analysis also indicated that one BAC clone (LE_HBa0258N07) that was previously assigned to chromosome 2 by overgo hybridization actually occurs on other chromosomes, but not on chromosome 2 (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

BAC clones used for the selection of “seed” BAC clones

| Marker | Position in linkage group 2 | BAC | Hybridization patterna |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1238 | 13 | LE_HBa0303I24 | 1 |

| T0888 | 13 | LE_HBa0306D07 | 4 |

| CT140 | 16 | LE_HBa0163K16 | 1 |

| T1706 | 18 | LE_HBa0025N15 | 1 |

| T0869 | 21 | LE_HBa0280E02 | 1 |

| SSR40 | 22 | LE_HBa0107I05 | 4 |

| SSR66 | 25 | LE_HBa0209K17 | 1 |

| cLED-19-B18 | 28 | LE_HBa0025A22 | 1 |

| T1768 | 31 | LE_HBa0282E10 | 4 |

| T1698 | 34 | LE_HBa0320M09 | 1 |

| T1361 | 34 | LE_HBa0052L14 | 4 |

| SSR96 | 36.5 | LE_HBa0155H19 | 2 |

| SSR104 | 37 | LE_HBa0155C04 | 1 |

| T1668 | 37 | LE_HBa0168N10 | 1 |

| T0683 | 38 | LE_HBa0160F05 | 1 |

| T1516 | 42 | LE_HBa0060P24 | 2 |

| T1516 | 42 | LE_HBa0123G24 | 4 |

| cLEC-27-M9 | 46 | LE_HBa0066C13 | 1 |

| T1654 | 46 | LE_HBa0134A15 | 1 |

| TG451 | 46 | LE_HBa0168N18 | 4 |

| cLPT1E8 | 47 | LE_HBa0002C08 | 4 |

| TG139 | 57 | LE_HBa0139G01 | 4 |

| T0266 | 66 | LE_HBa0059M17 | 1 |

| T1532 | 69 | LE_HBa0273J19 | 1 |

| T1438 | 70 | LE_HBa0329G05 | 1 |

| T1625 | 72.5 | LE_HBa0323A14 | 1 |

| TG154 | 72.5 | LE_HBa0118P10 | 4 |

| TM34 | 73 | LE_HBa0204D01 | 1 |

| TG131 | 73.4 | LE_HBa0147E11 | 4 |

| T1537 | 74.5 | LE_HBa0320D04 | 1 |

| T0702 | 76 | LE_HBa0198A03 | 1 |

| T0086 | 76 | LE_HBa0105H04 | 4 |

| SSR26 | 77.5 | LE_HBa0291P19 | 1 |

| TM20 | 78 | LE_HBa0236H12 | 2 |

| TM20 | 78 | LE_HBa0221D04 | 4 |

| cLET1A5 | 79 | LE_HBa0238L13 | 4 |

| TG373 | 79.5 | LE_HBa0011A02 | 4 |

| T0759 | 82 | LE_HBa0060J03 | 1 |

| T1671 | 82 | LE_HBa0010B01 | 1 |

| CT229 | 82.5 | LE_HBa0121J22 | 4 |

| TG583 | 83.2 | LE_HBa0023K06 | 4 |

| C2_At4g38630 | 83.5 | LE_HBa0009K06 | 4 |

| T1535 | 88 | LE_HBa0164H08 | 1 |

| T1555 | 88 | LE_HBa0213A01 | 1 |

| TG48 | 92 | LE_HBa0016A12 | 1 |

| TG373 | 94 | LE_HBa0011A02 | 1 |

| cLED-19B24 | 100 | SL_EcoRI0010H16 | 4 |

| T1480 | 106 | LE_HBa0172G12 | 1 |

| d | 107 | SL_EcoRI0092M23 | 1 |

| P61 | 108 | LE_HBa0046M08 | 1 |

| cLEC-7-L24 | 108 | LE_HBa0124N09 | 4 |

| T1158 | 108 | LE_HBa0167P17 | 4 |

| T1158 | 109 | LE_HBa0150M11 | 4 |

| TG34 | 111 | LE_HBa0046M08 | 4 |

| cTOB-9-L18 | 112 | LE_HBa0111M10 | 1 |

| cLPT-1-A21 | 114 | LE_HBa0210D10 | 1 |

| T1744 | 117 | LE_HBa0208N01 | 4 |

| TG167 | 118 | LE_HBa0266G08 | 4 |

| T1400 | 119 | LE_HBa0194N24 | 4 |

| U153274 | 120 | LE_HBa0073P13 | 1 |

| T0706 | 128 | LE_HBa0080H21 | 4 |

| T0634 | 130 | LE_HBa0155D20 | 1 |

| CT24 | 140 | LE_HBa0064B17 | 1 |

| T1096 | 141 | LE_HBa0194L19 | 1 |

| T1202 | 142 | LE_HBa0257H21 | 1 |

| T1554 | 142 | LE_HBa0177F12 | 1 |

| T1566 | 142 | LE_HBa0258N07 | 3 |

| cLEF-2-A11 | 142 | LE_HBa0219K15 | 4 |

| SSR50 | 143 | LE_HBa0256J01 | 4 |

1, hybridized only on pachytene chromosome 2; 2, hybridized on multiple chromosomes; 3, hybridized on chromosomes other than chromosome 2; 4, no hybridization.

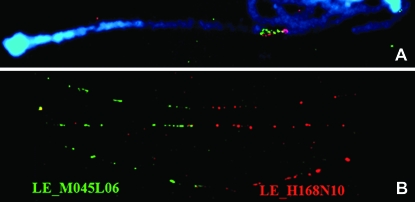

BAC– and fiber-FISH used for the confirmation of “next” BAC candidates:

After identifying the sequences of seed BAC clones, we selected “next” BAC clones using a BLASTN search of the BAC end-sequence (BES) database of the SGN (http://www.sgn.cornell.edu/tools/blast/). Of the next BAC candidate clones that matched seed BAC sequences, those having minimal overlap with seed BAC sequences were selected as next BAC clones. We also filtered repetitive BES to reduce the occurrence of false clone picks.

However, it is possible that seed BAC sequences and BES could contain additional repetitive sequences that we had not previously curated. Therefore, Dual-color BAC–FISH analyses using seed BAC clones and next BAC clones were used to confirm the selection of next BAC clones (Figure 6). For example, the digoxigenin-labeled seed BAC clone LE_H168N10 overlapped with the biotin-labeled next BAC clone LE_M045L06 (Figure 6A). However, extended DNA fiber-FISH clearly resolved the two BAC clones (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.—

Confirmation of “next” BAC clones. (A) After “seed” BAC clone sequencing, we performed a BLASTN search of BAC end sequences. The selected next BAC candidates were verified using BAC–FISH. Digoxigenin-labeled seed BAC clones LE_H168N10 (red) and biotin-labeled next BAC candidates LE_M045L06 (green) were hybridized with pachytene chromosome 2. Colocalized red and green signals indicate that the analyzed next BAC clones are located next to the seed BAC clones in the tomato genome. (B) Both clones were then hybridized with extended DNA fiber (DNA from interphase nuclei, which have been extended into individual fibers).

DISCUSSION

We defined the cytological architecture of tomato chromosome 2, including the location of the euchromatic block, and we integrated the recombination-based linkage map and the FISH-based physical map. This information is important in establishing a guide for genome sequencing and map-based gene cloning.

Microscopic observation of DAPI-stained pachytene chromosome 2 indicated a mean length of 70.22 μm. Of this, 48.12 μm was classified as a single euchromatic region. Taking 26 Mb as the total euchromatin of chromosome 2 gave a base pair/micrometer value for euchromatin of the pachytene chromosome of 540 kb/μm. Previous studies reported that the DNA compactness in euchromatin corresponds to 0.6 Mb/μm (Arumuganathan and Earle 1991; Peterson et al. 1996; Budiman et al. 2004). Thus, although different chromosomes and independent chromosome-spreading techniques were used, similar DNA compactness was determined, indicating that the mean base pair/micrometer relationship of euchromatin of the tomato pachytene is 0.5–0.6 Mb/μm.

To assess whether molecular marker loci existed for the distal ends of the chromosome arms, BAC probes corresponding to the ends of linkage group arms were hybridized to pachytene bivalents, and the physical locations of the FISH signals were examined. Most of the BACs derived from markers located between 0.0 and 12 cM showed multiple FISH signals in the pericentromeric heterochromatic region of all chromosomes, including the NOR or the pericentromeric heterochromatin of chromosome 2, except for one BAC (LE-HBa0155E05, 2 cM), which showed a single FISH signal in the heterochromatic region of the short arm of chromosome 2 (data not shown). Both FISH and DAPI data indicate that this segment may be composed of clusters of repetitive sequences. This result forced us to ignore this segment of the euchromatic region when selecting BAC clones for further sequencing projects. Thus, we used the euchromatic block between 13 and 142 cM for this project.

Comparing the linkage map EXPEN 2000 with our BAC–FISH map revealed an inversion in chromosome 2 (Figure 3, A2). This inconsistency in the position of the loci may have been caused by variation among the strains examined. Such apparent inversions have been reported in maize and tomato (Peterson et al. 1999). The order of the loci on the genetic and cytological maps was generally the same, as expected.

BAC–FISH maps sometimes allowed us to resolve the locations of markers that were not resolved on the linkage map. For example, both LE-HBa0213A01 and LE-HBa0164H08 were located at 88 cM in the linkage map. However, the BAC–FISH signals were separable (Figure 3, A3). This inconsistency in the position of the loci implies a low rate of recombination in the interval between them. The higher resolution of FISH mapping revealed physical gaps that could be troublesome for sequencing projects. FISH has been used to estimate the positions and sizes of gaps in the physical maps of rice and Arabidopsis. The linkage map of tomato reported by Tanksley et al. (1992) contains more markers per centimorgan than any other plant linkage map. However, chromosome 2 still contains four gaps (i.e., the absence of molecular marker-anchored BAC regions) that span >10 cM. BAC–FISH identified only one physical gap of 3.7–3.9 Mb, occurring between 46 and 66 cM, that is considered troublesome for further genome sequencing (Figure 3, A2).

Our data based on five BAC clones that spanned the entire euchromatin of chromosome 2 indicated that, on the average, 1 cM corresponds to 189 kb (range: 131–258 kb) to be compared with previous estimations of 330–1150 kb/cM (Tanksley et al. 1992; Giovannoni et al. 1995; Alpert and Tanksley 1996; Tor et al. 2002). Thus, our mean value is 16–56% as large as previous estimates. However, previous studies estimated the base pair/centimorgan relationship of specific regions, rather than of the entire chromosome (Tanksley et al. 1992; Giovannoni et al. 1995; Alpert and Tanksley 1996; Tor et al. 2002). Furthermore the genetic map they used was less saturated then the EXPEN 2000 map. The twofold differences in the base pair:centimorgan ratio between the G3 and G4 regions can be explained by higher recombination ratios in G4 than in G3. This is also consistent with the RN map of tomato (Richards and Ausubel 1988; Sherman and Stack 1995). To measure more localized base pair:centimorgan ratios of chromosome 2, we used 28 BAC clones that covered the entire chromosome 2 (Table 2 and Figure 3). Although most of the regions gave values close to the mean of 200 kb/cM, we observed a relatively hot spot (120–141 cM) and some cold spots (72–73, 106–108, and 141–142 cM) (Figure 4). Similar variation was observed in rice and Arabidopsis (Umehara et al. 1994; Schmidt et al. 1995).

Because RNs on synaptonemal complexes represent the site of crossovers (Anderson and Stack 2005) and are visible under transmission electron microscopy, we can estimate the accuracy of the integrated map of physical distance by comparing the centimorgan/micrometer relationship with the average number of RNs along the chromosome. Sherman and Stack (1995) measured the absolute positions of RNs on chromosome 2 and reported the number that occurred in each 0.1-μm segment. In Figure 5B we compare the RN distribution with the local centimorgan:micrometer ratios and find the trends in the two data sets to be similar. The DNA at both ends of the euchromatin block showed less recombination frequency than in the central region.

This may have occurred because recombination is low near the large 45S rDNA loci or telomeric repeats. This integration map will be valuable for estimating the physical structure of chromosome 2 before the chromosome is sequenced completely.

In the initial stage of genome sequencing, the marker-anchored BAC clones should be selected and termed as seed BAC clones. Because plants generally have many repetitive sequences the selection of accurate seed BAC clones is important. We used BAC–FISH analyses to select chromosome-2-specific seed BACs. We screened 69 seed BAC candidates that were previously selected by the Giovannoni and Tanksley groups at Cornell University, using overgo hybridization. FISH analysis identified 37 BACs that exhibited single strong FISH signals on pachytene chromosome 2; these were selected as the seed BACs. However, 46% of BAC clones identified by overgo hybridization resided on chromosomes other than chromosome 2. Some BAC–FISH signals detected on multiple chromosomes may be explained by the presence of repetitive sequences, so we do not know which chromosome segment was represented by these BAC clones. These FISH analyses imply that identifying the physical location of chromosome-specific BAC clones is important for this type of sequencing project.

BAC-based fingerprint contig (FPC), iterative hybridization, and sequence tag contig have been used successfully in sequencing the human, rice, and Arabidopsis genomes (Marra et al. 1997, 1998; Mayer et al. 1999; Mozo et al. 1999; McPherson et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2002; Pampanwar et al. 2005; Sasaki et al. 2005). A tomato FPC map was constructed using 88,640 BAC clones that covered the tomato genome 10 times. The map comprises 4385 contigs and 22,945 singletons; 82% of contigs are composed of <25 contig members. The small number of contig members prohibits the application of the FPC map to the selection of next BAC clones. Alternatively, we used a BLASTN search of the SGN database for BES to select next BAC candidates that overlapped the sequences of seed BAC clones. Considering the complexity of plant genomes, a BLASTN search using <1 kb BESs has the potential to identify the wrong chromosomal segment. To overcome this problem, we used BAC– or fiber-FISH to confirm the accuracy of the BLASTN search results. Dual-color BAC–FISH using seed BAC clones and next BAC clones was successful (Figure 6A). Because fiber-FISH has higher resolution than BAC–FISH, it showed a clearer relationship between seed and next BAC clones (Figure 6B).

Compared to the three other techniques presently used for physical mapping, namely, DNA contigs (Mozo et al. 1999), cytogenetic stocks (Kunzel et al. 2000), and in situ hybridization (Cheng et al. 2001a,b), the use of BAC–FISH for the integration of cytogenetic and genetic linkage maps, as in this study, is advantageous in terms of speed, accuracy, and applicability to a broad spectrum of organisms. Polyploidy and heterochromatin reduce the usefulness of contigs. For some species, the production of cytogenetic stocks is time consuming or impossible. Moreover, the resolution of the physical map obtained is comparatively low.

In situ hybridization techniques give varied resolutions depending upon such factors as genome size and ploidy. As shown in our study, a combination of cytogenetic and genetic methods can yield a high-resolution physical map.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Solanaceae Genome Network (Jim Giovanoni and Steve Tanksley) at Cornell University for providing all the tomato BAC resources. This work was supported by grants from the Crop Functional Genomics Center (CG1221) of the 21st Century Frontier Research Program funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Korean government.

References

- Alpert, K. B., and S. D. Tanksley, 1996. High-resolution mapping and isolation of a yeast artificial chromosome contig containing fw2.2: a major fruit weight quantitative trait locus in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 15503–15507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. K., and S. M. Stack, 2005. Recombination nodules in plants. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 109 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. K., N. Salameh, H. W. Bass, L. C. Harper, W. Z. Cande et al., 2004. Integrating genetic linkage maps with pachytene chromosome structure in maize. Genetics 166 1923–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan, K., and E. D. Earle, 1991. Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 9 208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. D., and J. B. Smith, 1976. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 274 227–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman, M. A., S. B. Chang, S. Lee, T. J. Yang, H. B. Zhang et al., 2004. Localization of jointless-2 gene in the centromeric region of tomato chromosome 12 based on high resolution genetic and physical mapping. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108 190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. B., 2004. Cytogenetic and molecular studies on tomato chromosomes using diploid tomato and tomato monosomic additions in tetraploid potato. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wageningen University, The Netherlands.

- Chang, S. B., L. K. Anderson, J. D. Sherman, S. M. Royer and S. M. Stack, 2007. Predicting and testing physical locations of genetically mapped loci on tomato pachytene chromosome 1. Genetics 176 2131–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M., G. Presting, W. B. Barbazuk, J. L. Goicoechea, B. Blackmon et al., 2002. An integrated physical and genetic map of the rice genome. Plant Cell 14 537–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z., G. Presting, C. R. Buell, R. A. Wing and J. Jiang, 2001. a High-resolution pachytene chromosome mapping of bacterial artificial chromosomes anchored by genetic markers reveals the centromere location and the distribution of genetic recombination along chromosome 10 of rice. Genetics 157 1749–1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z., C. R. Buell, R. A. Wing, M. Gu and J. Jiang, 2001. b Toward a cytological characterization of the rice genome. Genome Res. 11 2133–2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z., C. R. Buell, R. A. Wing and J. Jiang, 2002. Resolution of fluorescence in-situ hybridization mapping on rice mitotic prometaphase chromosomes, meiotic pachytene chromosomes and extended DNA fibers. Chromosome Res. 10 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz, P. F., S. Armstrong, J. H. de Jong, L. D. Parnell, C. van Drunen et al., 2000. Integrated cytogenetic map of chromosome arm 4S of A. thaliana: structural organization of heterochromatic knob and centromere region. Cell 100 367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach, O. L., and J. R. Bedrock, 1979. Cloning and characterization of ribosomal RNA genes from wheat and barley. Nucleic Acids Res. 109 1346–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni, J. J., E. N. Noensie, D. M. Ruezinsky, X. Lu, S. L. Tracy et al., 1995. Molecular genetic analysis of the ripening-inhibitor and non-ripening loci of tomato: a first step in genetic map-based cloning of fruit ripening genes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 248 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haanstra, J. P. W., C. Wye, H. Verbakel, F. Meijer-Dekens, P. v. d. Berg et al., 1999. An integrated high-density RFLP-AFLP map of tomato based on two Lycopersicon esculentum x L. pennellii F2 populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 99 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, S. A., M. L. Wang, H. M. Goodman and J. Jiang, 1998. Application of fiber-FISH in physical mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome 41 566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo, D. H., P. Plaha, Y. P. Lim, Y. Hur and J. W. Bang, 2004. A high-resolution karyotype of Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis revealed by pachytene analysis and multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization. Theor. Appl. Genet. 109 1346–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzel, G., L. Korzun and A. Meister, 2000. Cytologically integrated physical restriction fragment length polymorphism maps for the barley genome based on translocation breakpoints. Genetics 154 397–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra, M. A., T. A. Kucaba, N. L. Dietrich, E. D. Green, B. Brownstein et al., 1997. High throughput fingerprint analysis of large-insert clones. Genome Res. 7 1072–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra, M. A., L. Hillier and R. H. Waterston, 1998. Expressed sequence tags–EST abolishing bridges between genomes. Trends Genet. 14 4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, K., C. Schuller, R. Wambutt, G. Murphy, G. Volckaert et al., 1999. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 4 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 402 769–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, J. D., M. Marra, L. Hillier, R. H. Waterston, A. Chinwalla et al., 2001. A physical map of the human genome. Nature 409 934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson, M. J., H. J. Price, J. R. Ellison and J. S. Johnston, 1991. Comparison of plant DNA contents determined by Feulgen microspectrophotometry and laser flow cytometry. Am. J. Bot. 78 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mozo, T., K. Dewar, P. Dunn, J. R. Ecker, S. Fischer et al., 1999. A complete BAC-based physical map of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Nat. Genet. 22 271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, L. A., T. H. Solow, N. Taylor, B. Skwarecki, R. Buels et al., 2005. The SOL Genomics Network: a comparative resource for Solanaceae biology and beyond. Plant Physiol. 138 1310–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampanwar, V., F. Engler, J. Hatfield, S. Blundy, G. Gupta et al., 2005. FPC Web tools for rice, maize, and distribution. Plant Physiol. 138 116–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D. F., H. J. Price, J. S. Johnston and S. M. Stack, 1996. DNA content of heterochromatin and euchromatin in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) pachytene chromosomes. Genome 39 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D. G., N. L. Lapitan and S. M. Stack, 1999. Localization of single- and low-copy sequences on tomato synaptonemal complex spreads using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Genetics 152 427–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, E. J., and F. M. Ausubel, 1988. Isolation of a higher eukaryotic telomere from Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 53 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick, C. M., and J. I. Yoder, 1988. Classical and molecular genetics of tomato: highlights and perspectives. Annu. Rev. Genet. 22 281–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T., T. Matsumoto, B. A. Antonio and Y. Nagamura, 2005. From mapping to sequencing, post-sequencing and beyond. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R., J. West, K. Love, Z. Lenehan, C. Lister et al., 1995. Physical map and organization of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 4. Science 270 480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, J. D., and S. M. Stack, 1992. Two-dimensional spreads of synaptonemal complexs from solanaceous plants. V. Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) karyotype and ideogram. Genome 35 354–359. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, J. D., and S. M. Stack, 1995. Two-dimensional spreads of synaptonemal complexes from solanaceous plants. VI. High-resolution recombination nodule map for tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum). Genetics 141 683–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley, S. D., M. W. Ganal, J. P. Prince, M. C. de Vicente, M. W. Bonierbale et al., 1992. High density molecular linkage maps of the tomato and potato genomes. Genetics 132 1141–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tor, M., K. Manning, G. J. King, A. J. Thompson, G. H. Jones et al., 2002. Genetic analysis and FISH mapping of the Colourless non-ripening locus of tomato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umehara, Y., A. Inagaki, H. Tanoue, Y. Yasukochi, Y. Nagamura et al., 1994. Construction and characterization of a rice YAC library for physical mapping. Mol. Breed. 1 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- van der Knaap, E., A. Sanyal, S. A. Jackson and S. D. Tanksley, 2004. High-resolution fine mapping and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of sun, a locus controlling tomato fruit shape, reveals a region of the tomato genome prone to DNA rearrangements. Genetics 168 2127–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C. J., L. Harper and W. Z. Cande, 2006. High-resolution single-copy gene fluorescence in situ hybridization and its use in the construction of a cytogenetic map of maize chromosome 9. Plant Cell 18 529–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]