Abstract

In a prior study (Festinger et al., 2005) we found that neither the mode (cash vs. gift card) nor magnitude ($10, $40, or $70) of research follow-up payments increased rates of new drug use or perceptions of coercion. However, higher payments and payments in cash were associated with better follow-up attendance, reduced tracking efforts, and improved participant satisfaction with the study. The present study extended those findings to higher payment magnitudes. Participants from an urban outpatient substance abuse treatment program were randomly assigned to receive $70, $100, $130, or $160 in either cash or a gift card for completing a follow-up assessment at 6 months post-admission (n ≅ 50 per cell). Apart from the payment incentives, all participants received a standardized, minimal platform of follow-up efforts. Findings revealed that neither the magnitude nor mode of payment had a significant effect on new drug use or perceived coercion. Consistent with our previous findings, higher payments and cash payments resulted in significantly higher follow-up rates and fewer tracking calls. In addition participants receiving cash vs. gift cards were more likely to use their payments for essential, non-luxury purchases. Follow-up rates for participants receiving cash payments of $100, $130, and $160 approached or exceeded the FDA required minimum of 70% for studies to be considered in evaluations of new medications. This suggests that the use of higher magnitude payments and cash payments may be effective strategies for obtaining more representative follow-up samples without increasing new drug use or perceptions of coercion.

Keywords: Ethics, Follow-up, Research Payments, Coercion, Drug Abuse Research

1. Introduction

In treatment outcome studies, a follow-up rate of 70% to 80% is generally considered to be minimally acceptable for representing the baseline cohort and drawing generalizable conclusions from the research data (e.g., Bale, 1979; Coen et al., 1996; Gould and Lukoff, 1977; Polich et al., 1980). Accordingly, guidelines from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eliminate from consideration any study of a new medication or device that produced follow-up rates lower than 70% (FDA Regulatory Procedures Manual, 1999). Unfortunately, rates of follow-up in published large-scale community evaluations and controlled studies of drug abuse programs often fall well below 70% (e.g., Coen et al., 1996; Gerstein and Johnson, 2000; Hansen et al., 1990; Josephson and Rosen, 1978; Kleber and D'Aunno, 2001). Moreover, it is quite possible that many studies with lower follow-up rates were never published for the very reason that their follow-up rates were deemed to be unacceptable.

Many investigators have succeeded in attaining high follow-up rates exceeding 90% (e.g., Cottler et al., 1995; Meyers et al., 2003). However, this typically required the use of costly and intensive recontact procedures including frequent phone calls, multiple mailings, off-site meetings, and extensive in-person, telephone, mail, and internet tracking of family and other contacts. Such procedures require substantial training, manpower and wider time-windows for recontact.

A potentially effective and cost-efficient strategy for decreasing research attrition would be to provide substantial payment incentives to participants for attending follow-up interviews. If the payments were of a sufficient magnitude, this might reduce the need to employ other more costly and time consuming follow-up efforts. However, a number of serious, yet untested, ethical objections have been raised against the practice of using high-magnitude incentives for research participation. Among these objections are that (1) large incentives, particularly if they are provided in the form of cash, could trigger a relapse to drug use (Fry and Dwyer, 2001; Koocher, 1991; Rosenheck, 1997; Shaner et al., 1995); and (2) large incentives may be coercive (Dickert and Grady, 1999; Macklin, 1981; McGee, 1997), meaning they could compromise participants’ normal decisional processes and unduly entice them to participate even if they ordinarily would hold preferences against participation. As a result, researchers are often forced to use lower magnitude cash incentives or payments in the form of gift certificates or vouchers that must subsequently be exchanged for goods or services.

This is unfortunate because research clearly demonstrates that higher magnitude incentives increase rates of responding on a range of behaviors including drug abstinence, treatment attendance, and compliance with follow-up assessments (e.g., Dallery et al., 2001; Festinger et al., 2005; Silverman et al., 1999). Moreover, evidence suggests clients greatly prefer cash to vouchers and other non-monetary incentives (e.g., Amass et al., 1996; Festinger et al., 2005; Reilly et al., 2000; Schmitz et al., 1994; Stitzer et al., 1983). Cash is perceived as having greater worth than vouchers of the same value (Rosado et al., 2005). Cash payments also avoid the exchange delay inherent in redeeming other forms of incentives such as gift cards or vouchers. Contingency management studies have clearly identified a negative correlation between the efficacy of reinforcement and the delay interval between the target behavior and the delivery of the reinforcer (Roll and Higgins, 2000). Finally, cash incentives can be used for virtually any acquisition whereas the utility of vouchers or gift cards are limited to the inventory available in a store or the distance of the store from the participant’s residential location.

In a prior study (Festinger et al., 2005), we randomly assigned 350 outpatient drug abuse treatment clients to receive $10, $40, or $70 in either cash or gift cards for attending a 6-month follow-up research appointment. We implemented highly standardized, yet relatively minimal, follow-up procedures to ensure participants were otherwise treated equivalently across the research conditions. Participants who attended the 6-month follow-up were asked to provide a urine specimen and complete a brief structured inventory to assess how coerced they felt to attend the follow-up appointment. Participants then received their randomly assigned incentive payment and were asked to return again for a post-follow-up assessment 3 days later. At the post-follow-up assessment, participants were asked to provide a second urine specimen, complete a research satisfaction survey, and answer several questions about how they used their payments. Participants received a $40 gift card for attending the post-follow-up assessment.

Findings revealed that neither the mode (cash vs. gift card) nor magnitude ($10, $40 or $70) of the payments had a significant effect on rates of new drug use or perceptions of coercion. Findings further revealed that higher-magnitude cash payments were associated with higher follow-up rates, fewer tracking efforts, greater satisfaction with the research study, and a greater willingness to participate in research studies in the future. The purpose of the current study was to extend this line of research by determining whether the absence of untoward effects for payment incentives extends to higher-magnitude payment intervals of $100, $130, and $160 and whether higher follow-up rates and fewer tracking efforts could be achieved with larger magnitude and cash incentives.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

In a 2 × 4 parametric design, we randomly assigned 419 consenting outpatient substance abuse treatment clients to be offered different magnitudes of payment incentives ($70, $100, $130, or $160) in either cash or gift cards for attending a 6-month post-intake follow-up assessment. Participants were recruited from a large outpatient substance abuse treatment program located in central Philadelphia, PA. The program offers drug-free intensive outpatient treatment (group and individual) as well as comprehensive assessment, case management, and aftercare services. Consecutive admissions were approached for recruitment within 2 weeks of their admission to the program. Of the 421 clients who were approached for participation, only two chose not to participate in the study (one reporting time constraints and the other providing no reason for declining). Using block randomization to ensure approximately equal group sizes, each of the 419 consenting participants was assigned to one of the eight study conditions.

The average age of the participants was 36.54 years (SD = 10.04). The majority of the sample was male (57%), African American (60%) or Caucasian (31%), never married (72%), and unemployed (58%). The mean annual income was $6,485 (SD = $10,522) with a median of $1,500, and the average number of years of education was 11.16 (SD = 1.99). Nearly half of participants reported cocaine (48%) as their primary drug of abuse, followed by alcohol (35%), marijuana (21%), and heroin (19%). The sum of these percentages exceeds 100% because several participants reported more than one substance as their primary drug of abuse. Participants reported an average of 3.23 (SD = 4.79) prior substance abuse treatment episodes.

2.2. Procedures

Following informed consent, participants completed a brief assessment battery administered by a trained research technician. The battery consisted of a basic demographic questionnaire and a detailed locator form to provide contact information to assist with follow-up efforts. The demographic questionnaire inquired about age, race, gender, living arrangements, annual income, employment status, and primary, secondary, and tertiary drugs of abuse. The locator form inquired about addresses and phone numbers where the participant could be reached, as well as names and contact information for other people (e.g., family members, friends, therapists, physicians, caseworkers, and probation and parole officers) who would know of the participants’ whereabouts if we were unable to contact them directly. All participants were then scheduled to attend a research follow-up appointment 6 months later and were provided with an appointment card listing the date and location of the scheduled appointment, the amount they would be remunerated ($70, $100, $130, $160) and the type of remuneration (cash or gift cards). The gift cards were redeemable at any store in a large centrally located, full-service shopping center situated within several blocks of the treatment program and easily accessible by many forms of public transportation. The shopping center encompasses a wide variety of stores providing groceries, clothing, household needs, healthcare products and medical prescriptions, electronics, and other specialty items.

We elected to start with $70 as the low-end payment magnitude because in our previous study $70 cash payments were found to produce no higher rates of new drug use or perceived coercion than $10 or $40 payments, and therefore could serve as a baseline reference point against which to compare the effects of higher magnitude incentives. Focus groups held at the treatment programs indicated that $30 increments were perceived as meaningfully different by clients. Therefore, we extended the payment levels to $100, $130, and $160.

Follow-up procedures were highly standardized to ensure participants in the different conditions were treated equivalently with the exception of the payment incentives. We maintained a minimal platform of follow-up efforts to ensure we could clearly observe the effects of the payment incentives. The follow-up efforts were limited to one reminder letter and one phone call designed solely to remind the participants about the amount of their payment incentives, the nature of the study, and where and when to report for their follow-up appointment. Tracking efforts were initiated 2 weeks before the scheduled 6-month appointment and ended either when the participant was successfully contacted or 4 weeks following the scheduled follow-up appointment. Once a participant was contacted by phone, no further follow-up efforts were made.

At the 6-month follow-up appointment, participants were asked to provide a urine specimen and complete a brief battery consisting of a follow-up Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992), and two measures described below that assessed their perceptions of coercion to participate in the study. Participants then received their assigned incentive payments and were asked to return 3 days later for a post-follow-up appointment. At the post-follow-up, they were asked to complete a research satisfaction survey, answer questions about what they did with their research payment incentives, and provide a second urine specimen. All participants received a $40 gift card for returning for the post-follow-up assessment. In our previous study, a $40 gift card was sufficient to bring back 91% of the individuals who had attended the 6-month appointment (Festinger et al., 2005).

2.3. Outcomes

Importantly, the independent variable in this study can be conceptualized as having been delivered in two stages. All participants were informed at intake about the amount and type of incentive they would receive at follow-up. This permitted the dependent variables relating to follow-up attendance and tracking efforts to be assessed for the entire cohort. Subsequently, for those participants who attended the 6-month follow-up, the incentives were delivered and the dependent variables related to new drug use, perceived coercion, satisfaction with the study, and use of the incentives were assessed for those individuals only. As such, the latter dependent variables were assessed conditionally; i.e., conditioned upon the participant having attended the follow-up. This is the only plausible way to have conducted this study and reflects what actually occurs in research practice. Ethical objections to payment incentives are conditioned upon the actual delivery of the incentives for research participation.

2.3.1. Follow-up attendance

Attendance was carefully recorded for both the 6-month follow-up appointment and the 3-day post-follow-up assessment.

2.3.2. New Drug Use

Urine specimens were collected at both the 6-month follow-up and the 3-day post-follow-up assessment. The specimens were tested using the ONTRAK TESTCUP™ for cannabis, opiates, amphetamines, phencyclidine, and cocaine, and the ONTRAK TESTSTIK™ for benzodiazepines and barbiturates. In most cases a determination of new usage was straightforward. For instance, a negative specimen at the 6-month follow-up followed by a positive specimen at the post-follow-up assessment would indicate new use, whereas a negative specimen at the post-follow-up assessment would indicate no new use. However, drug-positive urine specimens at both appointments could have reflected either new use or simply residual metabolites from the previous use. Therefore, when both urine samples tested positive (n = 59), the two specimens were sealed, refrigerated, and sent to a certified lab where they were tested quantitatively using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCMS). New drug use was indicated if the level of drug metabolite in the second specimen exceeded or was equal to that of the first. Because most drugs of abuse are only detectable in urine for several days, and assuming that most participants who would spend their money on drugs would do so within a few days, if at all, participants who arrived for their post-follow-up assessment more than 7 days following the 6-month follow-up were not asked to provide a urine specimen. Under those circumstances, the urine data were analyzed both by treating missing specimens as missing and also by imputing missing specimens to represent new drug use.

2.2.3. Perceived Coercion

We could locate no standardized instrument that is designed to measure perceptions of coercion to participate in a research study. Therefore, as in our previous study (Festinger et al., 2005) we used a modified version of the Perceived Coercion Scale of the MacArthur Admission Experience Survey (MAES; Gardner et al., 1993). This five-item, true/false scale was originally designed to measure perceptions of coercion to enter inpatient psychiatric treatment. We replaced the word “hospital” in the items with the term “follow-up” to make it relevant for our purposes. A sample item was: “I felt free to do what I wanted about coming in for follow-up.” We subsequently dropped two of the five items because they were found to be significantly suppressing internal consistency (alpha). The resulting three-item scale had a range of 0 to 3 and a Cronbach’s alpha of .67.

The MAES, like virtually all coercion scales, focuses on negative or punitive pressures rather than on excessive positive inducements. To address this limitation, we developed our own questionnaire to assess the specific influence of the payment incentives on follow-up attendance. This questionnaire, referred to as the Positive Inducement Inventory (PII), assesses the amount of enticement experienced by the research participants. The measure consists of eight 4-point likert-type scale questions (from 0 to 3), yielding a possible range of 0 to 24. Because this measure was developed for this study, it has no established psychometric evidence to support its validity or reliability. Sample items include: (1) “The only reason I attended this follow-up was for the payment,” and (2) “The payment overtook my better judgment about coming in for this follow-up appointment.” The measure demonstrated adequate internal consistency in our sample (coefficient alpha = 0.75).

2.3.4. Research satisfaction

We could locate no standardized instrument that measures satisfaction with a research study. Therefore, we had participants complete a modified version of the Client Satisfaction Survey (CSQ; Larsen et al., 1979), which is an eight-item scale designed to measure patients’ satisfaction with treatment services. The eight CSQ items are each scored on a four-point Likert-type scale (from 1 to 4), yielding a possible range of 8 to 32. We modified the questions slightly by referring specifically to our research procedures rather than to treatment services. A sample item was: “How would you rate the quality of our research procedures?” An examination of the revised instrument’s reliability indicated adequate internal consistency in our sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .71).

2.3.5. Use of incentive payments

For descriptive purposes, we inquired of all participants how they used their payment incentives. The responses were independently coded by two research technicians into 8 categories: household/personal needs, debts/bills, transportation, non-essential clothing, gifts, luxury items (e.g., electronics, music, and entertainment), cigarettes, and illicit drugs. The two raters obtained 96% interrater reliability in their coding. The few coding discrepancies were discussed and a final result was determined by consensus with the Principal Investigator. These categories were subsequently dichotomously coded by the independent raters as either “essential” or “non-essential” items. Essential items included household items, groceries, non-luxury clothing, bills, and transportation, whereas non-essential items included gifts, luxury items, cigarettes, alcohol, and illicit drugs. The raters obtained 98% agreement on this dichotomous coding.

2.3.6. Tracking efforts

Research assistants carefully logged the number of phone calls they were required to make to contact each participant during the 6-week follow-up window. This permitted us to make a preliminary assessment of the relative ease with which we were able to locate participants in the different incentive conditions.

2.4. Data analyses

Table 1 presents the flow of participants in the study. Of the 419 original consenting participants, 13 were subsequently excluded from analyses due to circumstances unrelated to the study and prior to receiving their payment incentive, including incarceration (n = 11), severe cognitive impairment (n = 1) and death (n = 1), resulting in a final cohort of 406 participants. A total of 250 (62%) of the 406 participants returned for their 6-month follow-up appointment. Importantly, participants were required to attend their 6-month follow-up appointment in person to receive their incentive payment. However, once the incentive had been delivered, we wanted to collect as much post-follow-up data as possible. Therefore, if it became clear that a participant was not going to return in person for a second appointment, the post-follow-up interviews were completed by phone after confirming the individual’s identity. Under these circumstances, the participant did not provide a urine specimen and the $40 gift card was sent to them by mail. Analyses were then conducted treating missing samples as missing and also by using a conservative approach of imputing missing specimens as new drug use. Of the 250 participants who attended the 6-month follow-up and received their predetermined incentive payment, 222 (89%) completed a post-follow-up assessment either in person (n = 192) or by telephone (n = 30). Of the 192 participants who completed their post-follow-up assessment in person, 33 did not complete the post-follow-up assessment within 7 days of their 6-month follow-up and therefore were not asked to provide a urine specimen, 2 refused to provide a urine specimen, and 10 had invalid urine results due to laboratory testing errors. Consequently, valid urine drug screen data were available on 147 (59%) of the participants.

Table 1.

Flow of participants in the study

| Cash |

Gift Card |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $70 | $100 | $130 | $160 | $70 | $100 | $130 | $160 | TOTAL | |

| Randomly assigned at baseline | 52 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 419 |

| Dropped for purposes unrelated to the study | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

| Final study cohort | 50 | 50 | 52 | 51 | 49 | 51 | 51 | 52 | 406 |

| Attended 6-month follow-up | 27 (54%) | 36 (72%) | 36(69%) | 36 (71%) | 20 (41%) | 27(53%) | 35 (69%) | 33 (63%) | 250 (62%) |

| *Completed 3-day post-follow-up interviews (% of 6-month sample) | 21 (78%) | 29 (80%) | 35 (97%) | 28 (78%) | 20 (100%) | 25 (93%) | 33 (94%) | 31 (94%) | 222 (89%) |

| Provided valid 3-day post-follow-up UA (% of 6-month sample) | 12 (44%) | 19 (53%) | 25 (69%) | 18 (50%) | 17 (85%) | 17 (63%) | 20 (57%) | 19 (58%) | 147 (59%) |

Includes participants who completed the 3-day post-follow-up by phone or in person

Due to differential attrition throughout the course of the study (some of which was hypothesized to occur), data analyses were conducted in four phases (see Table 2). Analyses of follow-up rates and tracking efforts were performed on the entire intent-to-treat cohort (N= 406). Analyses of coercion (MAES & PII) and new drug use (counting missing urines as new drug use) were performed on participants who attended their 6 month follow-up (n = 250). Analyses of how participants used their incentives and satisfaction with the study were performed on participants who completed their post-follow-up assessment either by phone or in person (n = 222). Finally, analyses of new drug use (treating missing urine specimens as missing data) were performed on participants who completed their post-follow-up assessment in person within 7 days of their 6-month follow-up and provided a valid urine specimen (n = 147).

Table 2.

Outcomes by condition: mean (SD) or %

| Cash |

Gift Card |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $70 | $100 | $130 | $160 | $70 | $100 | $130 | $160 | Mode p-value | Magnitude p-value | Interaction p-value | |

| Intent to treat cohort (n=406) | |||||||||||

| Follow-up Rates | 54% | 72% | 69% | 71% | 41% | 53% | 69% | 63% | <.05 | <.01 | n.s. |

| Tracking Calls | 6.2 (5.8) | 5.1 (5.1) | 4.3 (4.6) | 4.1 (4.1) | 5.9 (5.3) | 5.2 (5.0) | 4.8 (4.4) | 4.3 (4.1) | n.s. | <.05 | n.s |

| Attended 6-month follow-up (n=250) | |||||||||||

| New Drug Use a (missing as drug positive) | 58% | 42% | 34% | 49% | 25% | 44% | 42% | 49% | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Any Coercion (MAES) | 17% | 6% | 3% | 12% | 11% | 8% | 12% | 6% | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Coercion Score (PII)b | 4.5 (4.4) | 6.4 (4.5) | 5.7 (4.2) | 6.8(5.3) | 6.1 (3.9) | 5.0 (3.7) | 4.9 (4.8) | 6.4 (3.7) | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Completed post-follow-up assessment by phone or in person (n=222) | |||||||||||

| Satisfaction with Study (CSQ) c | 29 (2.9) | 29 (2.9) | 30 (2.3) | 30 (2.3) | 30 (1.7) | 29 (2.3) | 29 (2.8) | 29 (2.7) | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Essential items Purchased | 65% | 45% | 51% | 32% | 15% | 12% | 12% | 13% | <.01 | n.s. | n.s. |

| Provided Valid Post-follow-up urine sample (n=147) | |||||||||||

| New Drug Use (UA confirmed) | 17% | 21% | 16% | 28% | 12% | 29% | 20% | 32% | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

New Drug Use reflects detected new use during the period between the follow-up and the 3-day post-follow-up.

Coercion Score (Positive Inducement Inventory; PII) is measured on an eight 4-point (0–3) likert-type scale yielding a score ranging from 0 to 24. Higher scores indicate greater levels of perceived coercion.

Satisfaction with the Study (Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; CSQ) is measured on an eight 4-point (1–4) likert-type scale yielding a score ranging from 8 to 32. Higher scores indicate greater levels of study satisfaction.

2.4.1. Detection of Covariates

Because there were differential rates of attrition at certain stages of the research (as hypothesized in some instances), the groups were compared at each stage on a range of baseline characteristics (i.e., age, race, gender, income, marital status, current legal involvement, number of prior treatment attempts, and primary drug problem) to detect potential covariates that would need to be controlled for. First, to examine the integrity of randomization, participants in each of the eight experimental conditions were compared on baseline demographic and drug-use variables using chi-square analysis for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. No differences were found among participants in any of the experimental groups for any of the variables examined. This procedure was subsequently repeated at each stage of the analyses to examine differential attrition. No between-group differences were observed for any of these variables at any stage in the analyses. This suggests that differential attrition was attributable either to the experimental manipulation or to equivalent factors operating across the conditions and is unlikely to have been due to confounding factors unrelated to the study hypotheses.

In addition, to rule it out treatment status as an alternative explanation for our findings, we examined between-group differences on participants’ treatment status at 6-month follow-up. We conducted a logistic regression to identify group differences in treatment status (i.e., any outpatient or inpatient treatment within the 30 days prior to the follow-up). Results indicated no effects of condition on treatment status, suggesting that outcomes were not influenced by involvement in treatment at the time of the follow-up appointment.

2.4.2. Analytic Procedures

Logistic regression was used to examine the effects of the mode and magnitude of payment and their interaction on binary outcomes (i.e., follow-up rates (attended/not attended), new drug use (yes/no), MAES perceived coercion (any coercion item endorsed/no coercion item endorsed), and use of incentives (any essential /no essential purchase). Endorsement rates for the MAES items were very low with no participant endorsing more than one item. Resulting scale scores therefore ranged from 0 to 1 requiring us to treat the measure as a binary outcome. Two-factor analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine continuous outcomes (i.e., tracking efforts, PII scores, and satisfaction). Each analysis included terms for mode, magnitude, and the mode-by-magnitude interaction.

3. Results

3.1. Follow-up rates

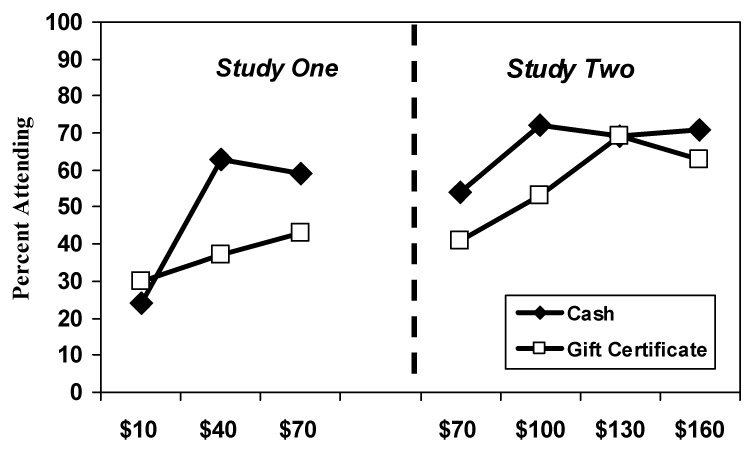

The follow-up rates for each condition are depicted in Figure 1. Outcomes from our previous study (Festinger et al., 2005) are also presented as a point of reference for lower dollar values. A logistic regression analysis on data from the current study indicated a main effect for magnitude, LR X2 (3)= 11.90, p = .008. Specific contrasts revealed that participants in the $100 (OR = 1.89), $130 (OR = 2.47), and $160 (OR = 2.27) conditions were more likely to attend the six-month follow-up than participants in the $70 condition. There were no significant differences between the $100, $130, and $160 conditions. In addition, participants who received cash were more likely to attend the follow-up than participants who received gift cards, LR X2 (1)= 4.20, p = .04. The follow-up rate was 66% among participants receiving cash and 57% among participants receiving gift cards (OR = 1.53). The interaction between mode and magnitude of payment was not significant, LR X2 (3)= 1.91, p = .59.

Figure 1.

Follow-up rates by mode and magnitude. Study 1 = Festinger et al. (2005)

3.2 Tracking efforts

A two-factor ANOVA indicated a significant effect of the magnitude of payment on the number of calls that were required to contact participants, F(3, 392) = 2.80, p = .04. Participants scheduled to receive $160 required significantly fewer phone calls (M = 4.20, SD = 4.09) than participants scheduled to receive $70 (M = 6.04, SD = 5.52). There were no differences as a function of mode, F(1, 392) = .03, p = .87, and no mode × magnitude interaction, F(3, 392) = .12, p = .95.

3.3. New drug use

A logistic regression analysis indicated no effect of mode, LR X2 (1)= .08, p = .77 (w = .02), or magnitude of payment, LR X2 (3)= 2.96, p = .40 (w = .14), and no interaction effect, LR X2 (3)= .42, p = .94 (w = .05), on rates of new drug use (see Table 2). Because of the substantial number of participants who did not provide a second urine specimen, we conducted another logistic regression analysis coding all missing second urines as new drug use. Using this conservative approach we obtained similar results (mode: LR X2 (1) = .1.64, p = .20 (w = .08), magnitude: LR X2 (3) = 5.06, p = .17 (w = .014); mode × magnitude: LR X2 (3) = 7.50, p = .06 (w = .17)). The effect sizes for both analyses were small according to Cohen’s criteria (1988). Treating missing urine specimens as instances of new drug use, there was a trend for a higher proportion of participants in the $70 gift-card condition to have less new drug use at their second follow-up as compared to the other conditions. However, because this analysis treated all missing urines as new drug use, this trend was due to the fact that a higher percentage of participants in the $70 gift card condition provided a second urine specimen. Perhaps because a $70 gift card was the lowest value and presented the least contrast against the $40 gift card that was paid for attending the post-follow-up assessment, it brought in relatively more participants for the second appointment. Individuals who only received a $70 gift card to begin with might have been more interested in earning an additional $40 gift card than, for example, those who already earned $160 in cash.

3.4. Perceived coercion

Ratings of perceived coercion as measured by the modified MAES were uniformly small across all experimental conditions. As indicated in Table 2, logistic regression analysis indicated no differences between the experimental groups on perceived coercion as a function of payment mode, LR X2 (1)= .15, p = .70 (w = .03), magnitude, LR X2 (3)= 1.90, p = .59 (w = .09), or their interaction, LR X2 (3)= 3.18, p = .36 (w = .12). Estimates of these effect sizes were small according to Cohen’s criteria (1988).

Similar results were found using the Positive Inducement Inventory (PII) developed for this study. A two-factor ANOVA indicated no significant differences between the groups as a function of mode, F (1, 235) = .19, p = .66, magnitude, F(3, 235) = 1.13, p = .34, or their interaction, F (3, 235) = .93, p = .43. Estimates of effect size (partial eta squared) were less than or equal to .01 for these effects.

3.5. Satisfaction with the research study

Self-reported satisfaction with the research study was uniformly high across the experimental conditions (see Table 2). A two-factor ANOVA indicated no significant differences in reported study satisfaction as a function of payment mode, F(1, 212) = .01, p = .91, magnitude, F(3, 212) = .81, p = .49, or their interaction effect, F(3, 212) = 1.96, p = .12.

3.6. Use of incentives

Table 3 presents participants’ self-reported purchases by condition. Importantly, no participants in either condition reported using their incentive payments for high-risk purchases such as alcohol, prostitutes, gambling, or firearms. The only exceptions are the 5 participants in each condition who reported purchasing cigarettes and the one participant in the cash condition who reported using his incentive to purchase illicit drugs. The two most frequently reported purchases for participants in the cash condition were debts/bills (29%) and household/personal needs (27%), whereas the most frequently reported purchases for participants in the gift card condition were non-essential clothing (58%) and gifts (20%).

Table 3.

Self-reported use of follow-up payments: Cash vs. gift card

| How participant used payment | Cash (n=109) | Gift Card (n=113) | Total (n=222) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential Purchases | |||

| Household/Personal Needs | 29 (27%) | 20 (18%) | 49 (22%) |

| Debts/Bills | 32 (29%) | 1 (1%) | 33 (15%) |

| Transportation | 13 (12%) | 2 (2%) | 15 (7%) |

| Non-essential Purchases | |||

| Non-essential Clothing | 24 (22%) | 65 (58%) | 89 (40%) |

| Gifts | 28 (26%) | 22 (20%) | 50 (23%) |

| Luxury Items | 28 (26%) | 15(13%) | 43 (19%) |

| Cigarettes | 5 (5%) | 5 (4%) | 10 (5%) |

| Illicit Drugs | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) |

Total % equals more than 100% as participants had the opportunity to purchase more than one item.

In our examination of the proportion of participants making any essential purchases, a logistic regression analysis indicated a significant effect of the mode of payment. A total of 47% of the participants in the cash condition reported purchasing any essential item compared to 12% of the participants in the gift card condition, LR X2 (1)= 30.99, p < .0001. There was no difference in the proportion of participants reporting any essential purchase as a function of the magnitude of the payment, LR X2 (3) = 2.04, p = .56, or the mode × magnitude interaction, LR X2 (3)= 1.37, p = .72.

4. Discussion

This paper reports on the effects of incentivizing research participants for attending a 6-month follow-up appointment using payments ranging from $70 to $160 in either cash or gift cards. The study extends our prior research which examined the effects of lower magnitude incentives ranging from $10 to $70. Consistent with our previous findings, larger magnitude incentives and incentives provided in cash led to higher 6-month follow-up rates and reduced the efforts required to track the participants for their follow-up appointments. Moreover, higher incentives and incentives paid in cash were not associated with greater risks in terms of perceived coercion or rates of new drug use.

This information may be useful not only for informing IRBs’ and investigators’ decisions about appropriate research payments, but also for informing clinical decisions whenever substance abusing clients come into contact with large amounts of cash. This may include earnings from gainful employment, government benefits, or even certain treatment regimens (e.g., contingency management protocols) in which clients may receive hundreds of dollars. Notably, participants in the current study received their incentive payments regardless of their clinical status or degree of sobriety. This might present greater ethical risks than those faced in traditional contingency management studies, in which payment is explicitly conditioned upon positive progress. This could suggest that contingency management protocols might be able to use substantially higher cash incentives without sacrificing clinical utility or client safety.

This study also provides information on a potentially useful and cost-efficient strategy for obtaining more representative follow-up rates. As discussed earlier, the validity of outcomes research depends largely on the ability to retain representative follow-up cohorts. To date, efforts to address this critical issue have focused on a relatively wide and varied set of strategies that are reportedly best used in combination such as frequent phone calls, multiple mailings, off-site meetings, and extensive in-person, telephone, mail, and internet tracking of family and other contacts, which require substantial manpower, training, and expenditures. The current study focused almost exclusively on participant remuneration, minimizing all other follow-up efforts, and still obtained reasonably acceptable follow-up rates, hovering at or above 70%.

Although it could be argued that a 70% follow-up rate may not be adequately representative, it does meet the FDA required minimum for clinical trials (FDA Regulatory Procedures Manual, 1999) to be acceptable in support of new medications. Moreover, because these rates were achieved with a minimal platform of other follow-up efforts, this could permit resources to be conserved and focused on the most transient and difficult-to-locate individuals. It also remains an open question whether even higher follow-up rates exceeding 80% or 90% could be achieved with larger dollar values.

In the current study, there were apparently no better effects for $130 or $160 payments than for $100 payments. On one hand, this could suggest that a ceiling effect had been reached. On the other hand, the shape of the relationship might not be linear at all payment levels, and might begin to accelerate again at some as yet undetermined higher value. Moreover, among participants of higher socioeconomic means, larger payment levels might be required to bring in representative cohorts.

4.1 Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the present study that must be considered. First, participation in both of our studies involved minimal risk and burden. Participants were merely asked to complete a follow-up interview. This may limit the ability to generalize these findings to studies involving greater levels of risk (e.g., biomedical trials) or those making increased time demands on participants.

Second, the study was conducted on a single cohort of low-income clients attending a publicly funded outpatient treatment program located in an inner-city metropolitan area. Consequently, it is not known whether the findings would generalize to other populations of substance abusers attending different treatment modalities located in other geographical locations or with different demographic characteristics. Future research should examine the use of high-magnitude cash incentives in different types of research protocols and with different clinical populations. For instance, substantially higher incentives might be required to bring in individuals of higher socioeconomic means.

Another potential limitation lies in the measurement of perceived coercion. Despite the hypothesized importance of this construct, we were unable to locate any instrument that specifically assesses coercion to enter research. Consequently we used a modified version of the MAES and an instrument developed specifically for this study (i.e., PII). Although these instruments demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current study, there is no literature available to support or refute their psychometric properties.

Finally, confidence in our findings may be limited by the fact that our primary ethics hypotheses required us to attempt to “prove” the null hypothesis. Because of the widely held beliefs that higher payments and cash payments have negative consequences, it falls on researchers to prove or disprove these untested assumptions. This presents a conceptual difficulty because, technically speaking, one can only fail to confirm the null hypothesis. Nevertheless, even if such negative effects are present, the results of our main analyses examining new drug use and perceived coercion resulted in exceedingly small effect sizes according to Cohen’s criteria (1988). Therefore, the magnitude of the influence would be relatively minor.

In summary, retaining representative cohorts is essential to the integrity of outcomes research. Inadequate follow-up rates seriously limit confidence in research findings and cast doubts on the validity of scientific conclusions. Fortunately, operant behavioral theory offers an effective and potentially cost-efficient solution to this problem in the form of participant incentives. The current study builds on prior research and sheds additional light on the safety and ethics of using this follow-up strategy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amass L, Bickel WK, Crean JP, Higgins ST, Badger GJ. Preferences for clinic privileges, retail items, and social activities in an outpatient buprenorphine treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(95)02060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale RN. The validity and reliability of self-reported data from heroin addicts: Mailed questionnaires compared with face-to-face interviews. Int J Addict. 1979;14:993–1000. doi: 10.3109/10826087909073942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen AS, Patrick DC, Shern DL. Minimizing attrition in longitudinal studies of special populations: An integrated management approach. Eval Program Plann. 1996;19:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM, Ben-Abdallah A, Horne M, Claverie D. Achieving a 96.6 percent follow-up rate in a longitudinal study of drug abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;41(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J, Silverman K, Chutuape MA, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Voucher-based reinforcement of opiate plus cocaine abstinence in treatment-resistant methadone patients: effects of reinforcer magnitude. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9(3):317–325. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond DP, Maddux JF, Johnson TH, Confer BA. Obtaining follow-up interviews for treatment evaluation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1995;12:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickert N, Grady C. What’s the price of a research subject? Approaches to payment for research participation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:198–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger DS, Marlowe DB, Croft JR, Dugosh KL, Mastro NK, Lee PA, DeMatteo DS, Patapis NS. Do research payments precipitate drug use or coerce participation? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78(3):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health. Regulatory Procedures Manual. Author: Rockville, MD; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fry C, Dwyer R. For love or money? An exploratory study of why injecting drug users participate in research. Addiction. 2001;96:1319–1325. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969131911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner W, Hoge SK, Bennet N, Roth LH, Lidz CW, Monahan J, Mulvey EP. Two scales for measuring patients’ perceptions of coercion during mental hospital admission. Behav Sci Law. 1993;11:307–321. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370110308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein DR, Johnson RA. Non response and selection bias in treatment follow-up studies. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;36(12):1749–1751. 1753–1757. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould LC, Lukoff I. Selecting a study design. In: Johnston LD, Nurco DN, Robins LN, editors. Conducting Follow-up Research on Drug Treatment Programs. (DHEW Publication No. ADM 77-487) Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1977. pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Tobler NS, Graham JW. Attrition in substance abuse prevention research: A meta-analysis of 85 longitudinally followed cohorts. Eval Rev. 1990;14:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson E, Rosen MA. Panel loss in a high school drug study. In: Kandel DB, editor. Longitudinal Research on Drug Use: Empirical Findings and Methodological Issues. New York: Wiley; 1978. pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kleber H, D'Aunno T. Large-scale evaluations of substance abuse treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend; 62nd Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; San Juan, PR. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, Hommer D. MRI visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. NeuroImage. 2000;12:20–27. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koocher GP. Questionable methods in alcoholism research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:249–255. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.59.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macklin R. “Due” and “undue” inducements: On paying money to research subjects. IRB. 1981;3:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers K, Webb A, Frantz J, Randall M. What does it take to retain substance-abusing adolescents in research protocols? Delineation of effort required, strategies undertaken, costs incurred, and 6-month post-treatment differences by retention difficulty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee G. Subject to payment? JAMA. 1997;278:199–200. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Kushner H, Peters R, Smith I, Pettinati H. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index: Cautions, additions and normative data. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 1992;9:461–480. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich JM, Armor DJ, Braiker HB. The Course of Alcoholism: Four Years After Treatment. Santa Monica: The Rand Corporation; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly MP, Roll JM, Downey KK. Impulsivity and voucher versus money preference in polydrug-dependent participants enrolled in a CM-based substance abuse treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST. A within-subject comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado J, Sigmon SC, Jones HE, Stitzer ML. Cash value of voucher reinforcers in pregnant drug-dependent women. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13:41–47. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.13.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R. Disability payments and chemical dependence: Conflicting values and uncertain effects. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:789–791. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JM, Rhoades H, Grabowski J. A menu of potential reinforcers in a methadone maintenance program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1994;11(5):425–431. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner A, Eckman TA, Roberts LJ, Wilkins JN, Tucker DE, Tsuang JW, Mintz J. Disability income, cocaine use, and repeated hospitalization among schizophrenic cocaine abusers: A government-sponsored revolving door. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:777–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509213331207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, Schuster CR. Efficacy and versatility of voucher-based reinforcement in drug abuse treatment. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, editors. Motivating Behavior Change Among Illicit-Drug Abusers: Research on Contingency Management Interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, McCaul ME, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Oral methadone self-administration: Effects of dose and alternative reinforcers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;34(1):29–35. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]