Abstract

Type I cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKGs) translocate to the nucleus to regulate gene expression in some, but not all cell types; we hypothesized that nuclear translocation of PKG may be regulated by extra-nuclear anchoring proteins. The inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor-associated cGMP kinase substrate (IRAG) binds to the N-terminus of PKG Iβ, but not PKG Iα, and in smooth muscle cells, IRAG and PKG Iβ are in a complex with the IP3 receptor at endoplasmatic reticulum membranes, where the complex regulates calcium release [Schlossmann et al., Nature, 404 (2000) 197]. We found that co-expression of IRAG and PKG Iβ in baby hamster kidney cells prevented cGMP-induced PKG Iβ translocation to the nucleus, and decreased cGMP/PKG Iβ transactivation of a cAMP-response element-dependent reporter gene. These effects required the PKG Iβ/IRAG association, as demonstrated by a binding-incompetent IRAG mutant, and were specific for PKG Iβ, as nuclear translocation and reporter gene activation by PKG Iα was not affected by IRAG. A phosphorylation-deficient IRAG mutant that is no longer functionally regulated by PKG phosphorylation suppressed cGMP/PKG Iβ transcriptional activity, indicating that IRAG’s effect was not explained by changes in intracellular calcium, and was not related to competition of IRAG with other PKG substrates. These results demonstrate that PKG anchoring to a specific binding protein is sufficient to dictate subcellular localization of the kinase and affect cGMP signaling in the nucleus, and may explain why nuclear translocation of PKG I does not occur in all cell types.

Keywords: cGMP-dependent protein kinase, anchoring proteins, IRAG, nuclear translocation, transcriptional regulation, cGMP signal transduction

1. INTRODUCTION

Type I cGMP-dependent protein kinases (PKGs) control multiple physiological functions, such as vascular tone and intestinal motility, platelet aggregation, neuronal development and synaptic plasticity, and growth and differentiation of several cell types, including neuronal cells, osteoblasts, and vascular smooth muscle cells [1–3]. Some of these effects occur by PKG regulating gene expression through transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms; transcriptional mechanisms involve nuclear translocation of type I PKG and phosphorylation of transcription factors such as cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB), activating factor-1 (ATF-1), and TFII-I [3].

In mammalian cells, two different genes encode type I and II PKGs [1]. Alternative splicing of the first two exons encoding the N-terminal dimerization domain of PKG I leads to expression of two isoforms, PKG Iα and PKG Iβ, which differ in the first ~ 100 amino acids [4]. The PKG I isoforms display different cGMP sensitivity and tissue distribution: PKG Iα is activated by lower concentrations of cGMP than PKG Iβ, and is highly expressed in cerebellum and dorsal root ganglia, whereas PKG Iβ is mainly found in platelets and hippocampus; both isoforms are expressed in smooth muscle [5,6]. PKG Iα and Iβ may also differ in subcellular localization and substrate specificity, because their N-terminal dimerization domains mediate binding to different interacting proteins. PKG Iα interacts with the regulator of G-protein signaling-2 (RGS-2) and the myosin binding subunit of phosphatase I [7,8], whereas PKG Iβ interacts with the IP3 receptor-associated cGMP kinase substrate (IRAG) and the multifunctional transcriptional regulator TFII-I [9,10]. IRAG appears to be stably integrated within the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, and PKG Iβ phosphorylation of IRAG inhibits IP3-induced Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, contributing to cGMP-induced smooth muscle relaxation [9,11]. TFII-I shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus, and interacts with multiple transcription factors and histone deacetylases; PKG Iβ phosphorylation of TFII-I appears to modulate TFII-I co-operation with other transcription factors [10].

Nitric oxide (NO) and natriuretic peptides activate soluble and receptor guanylate cyclases, respectively, thereby increasing intracellular cGMP concentrations and inducing expression of c-fos and junB mRNA in a variety of cultured cells and primary tissues [12–14]. Similar effects are observed when cells are treated with membrane-permeable cGMP analogs [3]. In intact animals, inhibitors of NO/cGMP signaling reduce c-fos expression in neuronal cells in response to various stimuli, supporting the physiological importance of NO/cGMP regulation of c-fos [15–17]. We showed previously that cGMP induction of c-fos occurs at the transcriptional level, and is mediated by PKG [10,18,19]. Type I PKG targets several cis-acting elements in the fos promoter, including the cAMP-response element (CRE) and the fos AP1 site, which both bind CRE-binding protein (CREB)-related proteins, and the serum response element, which binds multiple transcription factors including serum response factor, ternary complex factor, and TFII-I [10,18,19]. We demonstrated that NO/cGMP induction of the fos promoter requires CREB phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of PKG I in baby hamster kidney (BHK) fibroblasts and C6 glioma cells [19–21]. PKG I nuclear translocation occurs after a cGMP-induced conformational change, which exposes a nuclear localization signal [20]. PKG I constructs with mutations in the nuclear localization signal are excluded from the nucleus and are unable to activate c-fos, despite normal catalytic activity [20]. We and others have observed PKG I nuclear localization in fibroblasts, osteoblasts, neutrophils, and neuronal cells [14,19,20,22,23]. However, in other cell types, PKG I appears to be excluded from the nucleus, or nuclear staining is observed only in a minority of the cells [24–26]. Thus, nuclear translocation of PKG I is not a universal phenomenon. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that extra-nuclear PKG-interacting proteins may regulate the enzyme’s nuclear localization. We now demonstrate that PKG Iβ interaction with IRAG is sufficiently stable and of high enough affinity to inhibit PKG Iβ nuclear translocation and reduce cGMP transactivation of a CRE-dependent reporter gene. The effect was specific for PKG Iβ and independent of PKG phosphorylation of IRAG.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Reagents

The anti-Myc 9E10 (sc-40) and anti-PKG-CT (#539729) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Calbiochem, respectively. Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch. The cell-permeable cGMP-analogue 8-p-chlorophenylthio-cGMP (8-CPT-cGMP) was from Biolog.

2.2 DNA Constructs

The reporters pCRE-Luc and pRSV-βgal, and the mammalian expression vectors encoding PKG I isoforms [pCB6-PKG Iα, pCB6-PKG Iβ] and Myc epitope-tagged IRAG [pMYC-IRAG and pMYC-IRAG (R124A/R125A)] were described previously [19,27]. Throughout the text, IRAG refers to the IRAGb isoform [9], and amino acid residues are numbered accordingly. Vectors encoding IRAG/glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins [pCMVGST-IRAG and pCMVGST-IRAG (R124A/R125A)] were constructed by ligating the appropriate IRAG-containing fragment into a BamHI- and NotI-digested, modified version of pCMVGST [27]. IRAG S644A was constructed using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) as per the manufacturer’s instructions using the following set of primers: 5′-CCCCGCCGAAGGGTCGCGGTCGCCGTGGTGCCCAAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTTGGGCACCACGGCGACCGCGACCCTTCGGCGGGG-3′ (antisense) [27]. All mutant constructs were sequenced.

2.3. Cell Culture and Transfections

BHK, C6, and COS7 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum / 5% donor calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. For reporter gene studies, BHK or C6 cells were plated on 24 well culture dishes at 2.0 × 106 cells/dish and transfected 24 h later using Lipofectamine™ as described previously [20]. After a 1 h recovery in growth media, the cells were starved overnight in DMEM with 0.1% fetal bovine serum. Some cultures were treated for 7 h with 250μM 8-CPT-cGMP prior to harvesting. For interaction studies, BHK or COS7 cells were plated on 6 well culture dishes at 1.2 × 106 cells/dish and transfected with the indicated DNA constructs using Lipofectamine™ or Polyfect™, respectively, as described [27].

2.4. Immunofluorescence Studies

BHK cells were plated on etched glass slides and transfected with the indicated DNA constructs as described above. The cells were treated with 250 μM CPT- cGMP for 1 h where indicated. Cells were fixed with 2% fresh paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton-X 100, and blocked with 3% BSA [20]. Cells were then incubated with mouse anti-Myc (9E10) and rabbit anti-PKG-CT antibodies for 1 h, followed by incubation with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-mouse and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies. Stained cells were visualized using a Delta Vision Deconvolution Microscope System (Nikon TE-200 Microscope) in the UCSD Cancer Center Digital Imaging Core Facility.

2.5. Reporter Gene Assays

Luciferase and β-galactosidase assays were performed as described previously [20].

2.6. Immunoprecipitations, GST-Pulldown Assays, and Immunoblots

BHK or COS7 cells were transfected as described above, and 24 h later, cells were lysed in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% NP40 for 10 min on ice. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants were incubated with either anti-Myc antibody plus Protein-G agarose beads (Sigma) or glutathione sepharose beads (GE Health-care). After a 1 h incubation, the beads were washed with lysis buffer and bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE)/immunoblotting as described [10].

2.7. Phosphorylation Studies

BHK cells were transfected with PKG Iβ and Myc epitope-tagged IRAG constructs as described above. Twenty-four hours later, cells were transferred to phosphate-free DMEM and incubated with 100 μCi/ml of 32PO4 for 4 h. During the last hour, some cells were treated with 8-CPT-cGMP as indicated. IRAG was isolated by immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibodies and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/autoradiography as described [10].

2.8. Data Analysis and Statistics

Results represent the means ± standard deviations of at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate. The indicated pairs of data were analyzed using a one-tailed Students t-test; a p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effect of IRAG on the Subcellular Localization of PKG Iα and Iβ

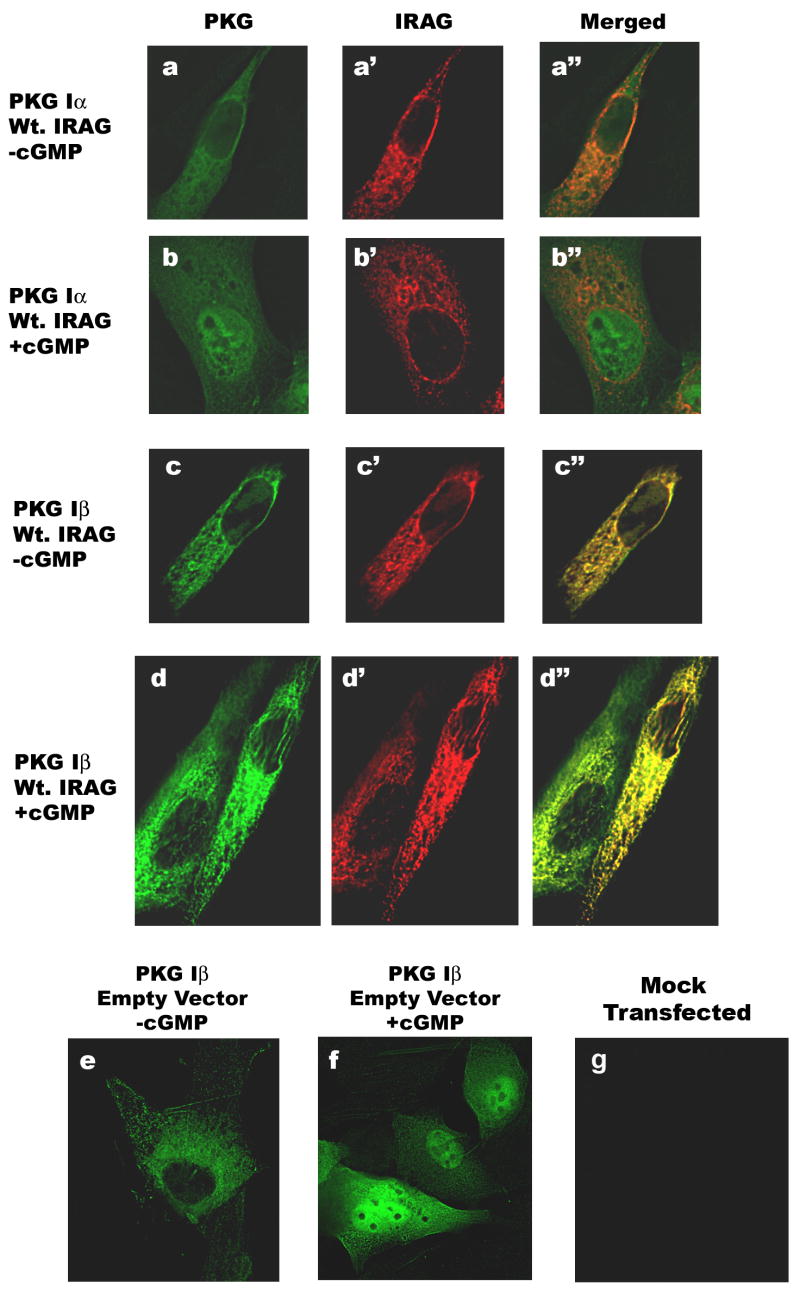

IRAG binds to the N-terminus of PKG Iβ and interacts with the intact Iβ, but not Iα isoform in transfected COS7 cells [11,27]. In vascular smooth muscle cells, PKG Iβ co-immunoprecipitates with IRAG, the IP3 receptor, and several other proteins, which appear to exist in a complex localized at the endoplasmatic reticulum membrane [9,28]. We previously showed nuclear translocation of PKG Iβ in BHK cells treated with membrane-permeable cGMP analogs [20]. BHK cells do not express significant amounts of endogenous PKG, and thereby afford the opportunity to examine the subcellular localization of individually transfected PKG I isoforms (as shown in Fig. 2b, top panel, and in a supplementary figure). To test the hypothesis that IRAG may localize PKG Iβ at microsomal membranes and prevent nuclear translocation, we transfected BHK cells with IRAG and either PKG Iα or Iβ, and examined the subcellular localization of both isoforms in cells cultured in the absence and presence of 8-CPT-cGMP. As shown in Fig. 1, PKG Iβ, but not PKG Iα, co-localized with IRAG in a punctate pattern suggesting association with endogenous membranes (compare panels a and b, cells transfected with PKG Iα, to panels c and d, cells transfected with PKG Iβ; in the merged images of panels c″ and d″ yellow fluorescence indicates co-localization). When the IRAG-expressing cells were treated with 8-CPT-cGMP, PKG Iα translocated to the nucleus, whereas PKG Iβ remained extra-nuclear (compare panels b and d). In control cells expressing PKG Iβ in the absence of IRAG, cGMP induced nuclear translocation of the kinase (Fig. 1f), as described previously [20]. Thus, IRAG association with PKG Iβ interfered with nuclear translocation of the kinase, suggesting that IRAG acted as an extra-nuclear anchor for PKG Iβ.

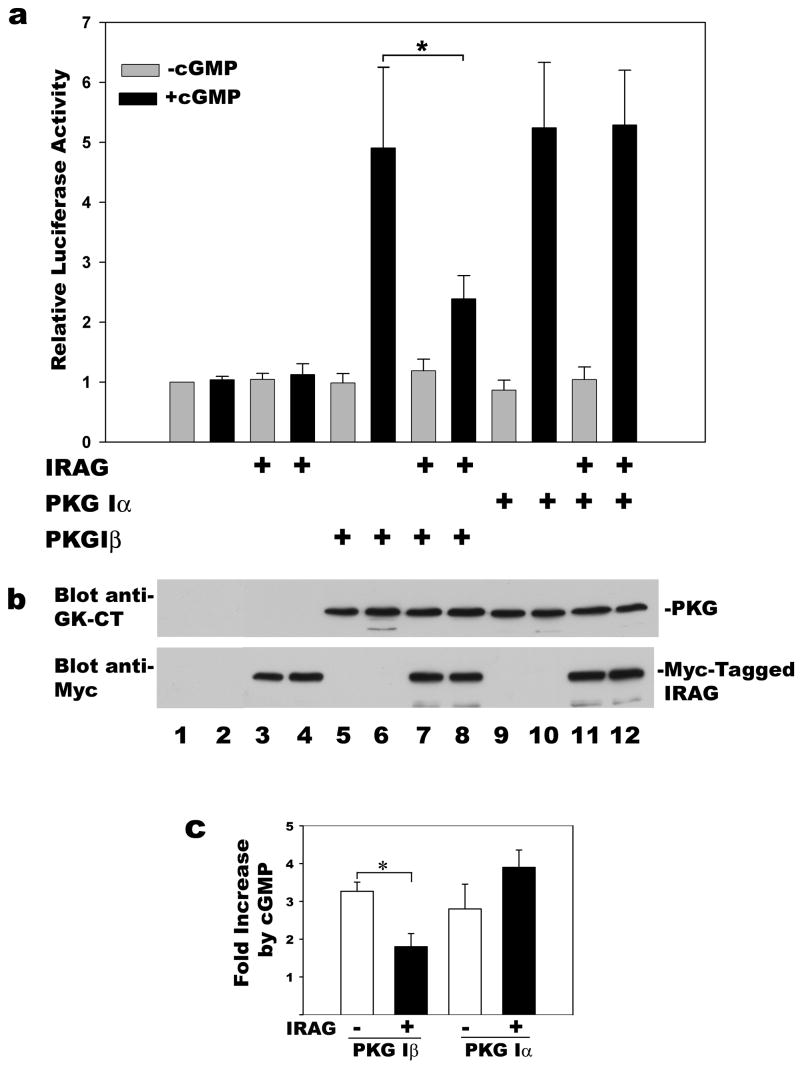

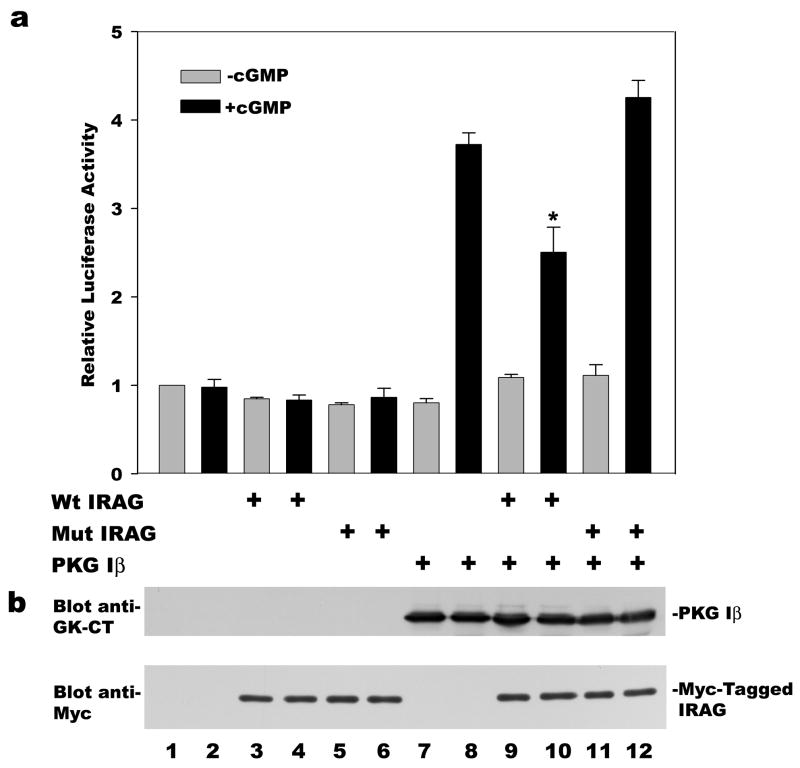

Figure 2. Effect of IRAG on PKG Iα- and Iβ-induced reporter gene expression.

BHK cells were co-transfected with the reporter pCRE-Luc, the control plasmid pRSV-βgal, and either empty vector or expression vectors encoding PKG Iα, PKG Iβ, and/or IRAG as indicated. Cells were serum-starved and cultured in the presence (black bars) or absence (grey bars) of 250 μM 8-CPT-cGMP (cGMP) for the last 7 h prior to harvesting. Panel a: Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods, and the luciferase/β-galactosidase ratio found in untreated cells transfected with empty vector alone was assigned a value of one. *p< 0.05 for the comparison between cGMP-treated cells transfected with PKG Iβ plus IRAG versus PKG Iβ plus empty vector. Panel b: Aliquots of cell extracts from a representative experiment shown in panel a were subjected to SDS-PAGE/Western 19 blotting with antibodies specific for the C-terminus of PKG I (top panel), or the Myc-epitope of IRAG (bottom panel). Panel c: C6 glioma cells were co-transfected with pCRE-Luc, pRSV-βgal and PKG Iα or Iβ as indicated; cells additionally received either empty vector (open bars) or IRAG (filld bars), and half of the cultures were treated with 8-CPT-cGMP as described in panel a. The data are expressed as the fold increase in reporter gene activity induced by cGMP. *p< 0.05 for the comparison between cells transfected with PKG Iβ plus or minus IRAG.

Figure 1. Subcellular localization of PKG I and IRAG.

PKG-deficient BHK cells were plated on glass coverslips and transfected with Myc epitope-tagged IRAG (panels a-d) and expression vectors encoding either PKG Iα (panels a and b) or PKG Iβ (panels c and d). Some cells were transfected with PKG Iβ plus empty vector (panels e and f). The cells in panels b, d, and f were treated with 250 μM 8-CPT-cGMP for 1 h prior to fixation. Immunofluorescence staining using a rabbit antibody directed against the common C-terminus of PKG Iα and Iβ (green fluorescence) and a mouse antibody against the Myc epitope on IRAG (red fluorescence) was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Images were obtained using a Delta Vision Deconvolution Microscope, and cells were sectioned at 2 μm intervals; mid-nuclear sections are shown. The PKG- and Myc-specific antibodies did not produce significant fluorescence signals in mock-transfected BHK cells (panel g).

3.2. Effect of IRAG on PKG Iα- and Iβ-induced Reporter Gene Expression

We previously showed that nuclear translocation of PKG I is required for cGMP-mediated transcriptional regulation of the fos promoter [20]. To examine the effect of PKG Iβ anchoring on the kinase’s ability to induce transcription, we transfected BHK cells with a CRE-dependent luciferase reporter construct and expression vectors for PKG Iα or Iβ, with or without IRAG. In PKG-deficient BHK cells, neither transfection of IRAG nor treatment with 8-CPT-cGMP had any effect on reporter gene activity (Fig. 2a). In BHK cells transfected with either PKG Iα or Iβ in the absence of IRAG, 8-CPT-cGMP stimulated CRE-dependent luciferase activity about 5-fold. Co-transfection of IRAG reduced the effect of cGMP/PKG Iβ on luciferase activity by more than 50%, whereas IRAG had no effect on cGMP/PKG Iα stimulation of the reporter gene (Fig. 2a, compare bars 6 and 8 for PKG Iβ, and bars 10 and 12 for PKG Iα; p< 0.05 for the comparison between cGMP-treated cells transfected with PKG Iβ plus IRAG versus PKG Iβ plus empty vector). IRAG did not affect reporter gene activity in the absence of cGMP. Figure 2b demonstrates that equal amounts of PKG Iα and Iβ were expressed, and that co-transfection of IRAG did not affect PKG levels. Possible reasons for the residual transcriptional effect of cGMP in PKG Iβ- and IRAG-expressing cells are discussed later. Similar results were obtained in C6 rat glioma cells: in PKG Iβ-transfected C6 cells, IRAG co-transfection inhibited cGMP-induced CRE-luciferase activity by 45 % (p < 0.05), but it had no significant effect in PKG Iα-transfected cells (Fig. 2c).

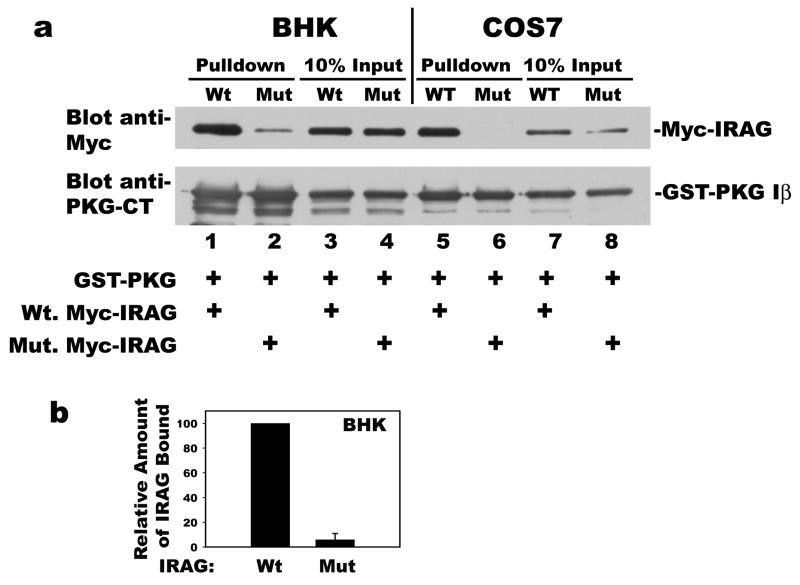

3.3. PKG Iβ Association with Wild Type Versus Mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A), and IRAG Self-association

We and others have shown that IRAG interacts with PKG Iβ, but not PKG Iα, in transfected COS7 cells [11,27]. The interaction between PKG Iβ and IRAG is mediated by negatively charged residues in the leucine zipper of PKG Iβ, and positively charged residues in IRAG [27]. Notably, site-directed mutation of two arginine residues in IRAG to alanines (R124A/R125A) disrupted the interaction with PKG Iβ in vitro and in COS7 cells, which do not express endogenous IRAG [9,27] (see also Fig. 3a; compare lanes 5 and 6). When we tested the interaction between mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) and PKG Iβ in BHK cells, it was reduced by > 90 %, but not completely eliminated (Fig. 3a, compare lanes 1 and 2; Fig. 3b summarizes the results of three independent experiments). Residual association of mutant IRAG with PKG Iβ in BHK cells could be explained, if IRAG formed higher order complexes (i.e. dimers), and small amounts of endogenous IRAG associated with the mutant IRAG, allowing PKG Iβ binding.

Figure 3. Association of PKG Iβ with wild type versus mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A), and self-association of IRAG.

Panel a: BHK cells (lanes 1–4) or COS7 cells (lanes 5–8) were transfected with expression vectors encoding GST-tagged PKG Iβ and either Myc-tagged wild type (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) as indicated in Materials and Methods. Cell lysates were incubated with glutathione sepharose beads, and after washing, proteins associated with the beads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/Western blotting with antibodies for the Myc-epitope of IRAG (top panel), or the C-terminus of PKG I (bottom panel). Ten percent of cell lysate input was analyzed in parallel (lanes 3 and 4 for BHK, and lanes 7 and 8 for COS7 cells). Panel b: Results of three independent experiments performed in BHK cells as described in panel a are summarized; the amount of wild type IRAG associated with PKG Iβ was assigned a value of 100. Panel c: COS7 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding GST (lanes 1, 2, 5 and 6) or GST-tagged wild type IRAG (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8); cells were co-transfected with either Myc-tagged wild type (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). Wild type IRAG was isolated on glutathione sepharose beads, and the association of wild type or mutant, Myc-tagged IRAG with the beads was analyzed as described in panel a (lanes 1–4); 20% of cell lysate input were analyzed in parallel (lanes 5–8).

To test whether IRAG forms higher order complexes, we transfected IRAG-deficient COS7 cells [10] with GST-tagged wild type IRAG and either wild type or mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) tagged with a Myc epitope. The GST-tagged IRAG was isolated on glutathione beads, and associated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE/immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3c, both Myc-tagged wild-type and mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) co-purified with GST-tagged wild type IRAG (lanes 3 and 4, respectively). There was no association of IRAG with GST alone (lanes 1 and 2). These results suggest that IRAG associates with itself, and could explain the presence of small amounts of PKG Iβ in mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) immunoprecipitates in BHK cells, due to endogenous IRAG in complex with the transfected mutant IRAG.

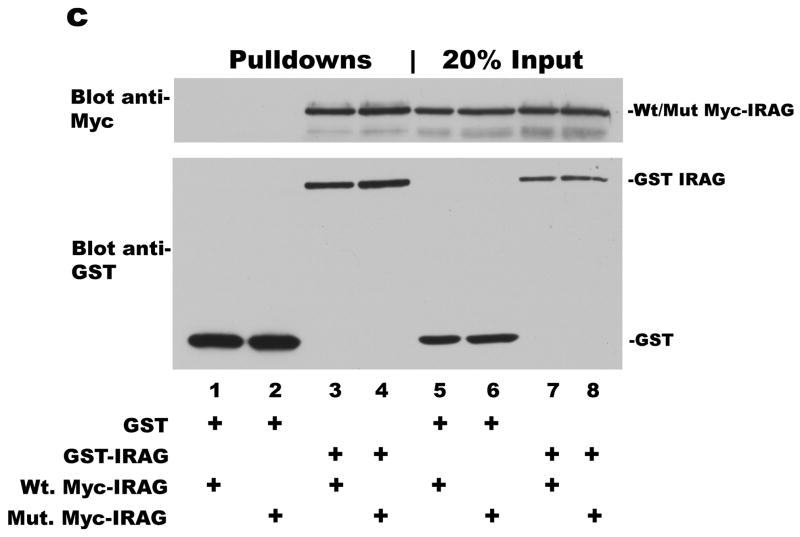

3.4. Inhibition of PKG Iβ-induced Reporter Gene Expression by Wild-type, But Not Binding-deficient, Mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A)

We compared the effect of wild type and PKG binding-deficient, mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) on PKG Iβ-induced reporter gene expression. Under conditions where wild type IRAG inhibited cGMP-stimulated luciferase expression in BHK cells co-transfected with PKG Iβ, IRAG (R124A/R125A) had no significant effect [Fig. 4a, compare bars 10 and 12, cells co-transfected with wild type or mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A), respectively]. Figure 4b demonstrates that equal amounts of wild-type and mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) were present, and that co-transfection of either IRAG construct had no effect on PKG Iβ expression levels. These results support the hypothesis that specific association of PKG Iβ with IRAG anchors the kinase, thereby restricting nuclear translocation and inhibiting its ability to mediate transcriptional effects.

Figure 4. Inhibition of PKG Iβ-induced reporter gene expression by wild-type, but not by binding-deficient, mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A).

BHK cells were transfected with pCRE-Luc, pRSV-βgal, and either empty vector or expression vectors encoding wild type or mutant IRAG (R124A/R125A) and/or PKG Iβ as indicated, and cells were cultured in the absence (grey bars) or presence (black bars) of 8-CPT-cGMP as described in Fig. 2. Panel a: Reporter gene activities were measured and luciferase activities were normalized to β-galactosidase activities as described in Fig. 2a. *p< 0.05 for the comparison between cGMP-treated cells transfected with PKG Iβ plus wild type IRAG versus PKG Iβ plus empty vector. Panel b: Aliquots of cell extracts from a representative experiment in panel a were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Fig. 2b.

3.5. Inhibition of PKG Iβ-induced Reporter Gene Expression by the Phosphorylation-deficient Mutant IRAG (S644A)

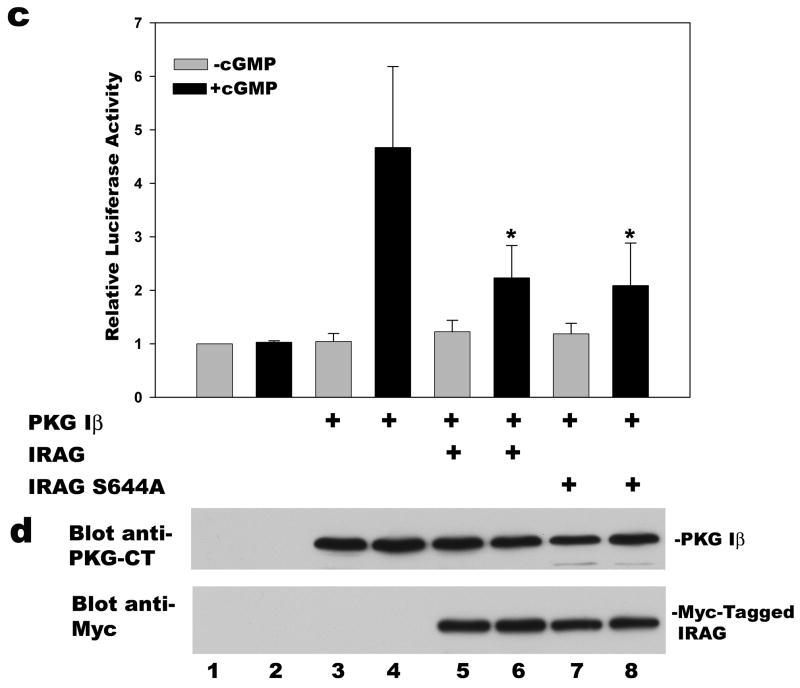

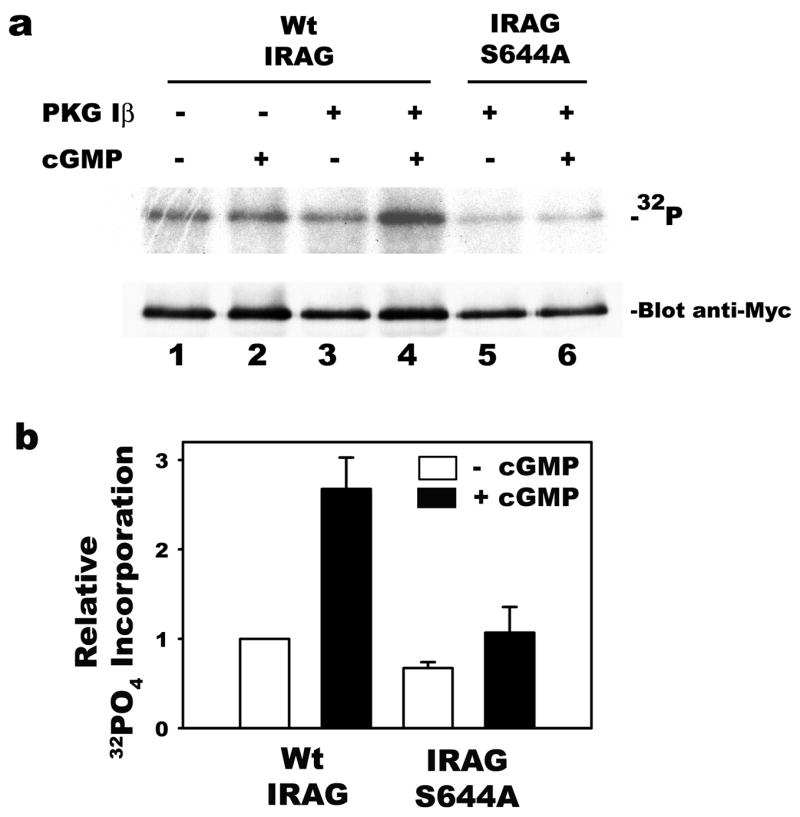

PKG Iβ phosphorylates IRAG predominantly on S644, which is required for cGMP-mediated regulation of Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores ([11]; S644 in IRAGb corresponds to S696 in IRAGa). In some cell types, Ca2+ positively regulates CRE-dependent transcription through Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-induced CREB phosphorylation, and IRAG expression could potentially reduce CRE-dependent reporter gene expression by lowering cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels [11,29]. Therefore, we compared the effect of wild type and phosphorylation-deficient, mutant IRAG (S644A) on cGMP/PKG Iβ-induced reporter gene expression. Mutation of serine 644 to alanine in IRAG eliminated the cGMP-induced, PKG Iβ-mediated IRAG phosphorylation in BHK cells (Fig. 5a, compare lanes 4 and 6, cells transfected with wild type and mutant IRAG S644A, respectively; Fig. 5b summarizes the results of three independent experiments). Co-transfection of mutant IRAG (S644A) inhibited cGMP/PKG Iβ-induced luciferase expression to the same extent as did wild type IRAG (Fig. 5c). Wild type and mutant IRAG (S644A) were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 5d). We previously showed that increasing intracellular Ca2+ concentrations with the Ca2+ ionophore A23187 has no effect on CRE-dependent reporter gene activity in BHK cells [18]. Therefore, the ability of co-transfected IRAG to decrease CRE transactivation by cGMP/PKG Iβ does not require IRAG phosphorylation by PKG, and is not explained by changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels.

Figure 5. Inhibition of PKG Iβ-induced reporter gene expression by a phosphorylation-deficient IRAG mutant.

Panel a: BHK cells were transfected with PKG Iβ and Myc epitope-tagged wild type (lanes 1–4) or mutant IRAG (S644A) (lanes 5 and 6); cells were labeled with 32PO4, and some cells (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were treated for 1 h with 250 μM 8-CPT-cGMP as described in Materials and Methods. IRAG was immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibodies and analyzed by SDS-PAGE/electroblotting/autoradiography (upper panel). Membranes were probed with anti-Myc antibodies to demonstrate similar amounts of IRAG present in the immunoprecipitates (lower panel). Panel b: Three independent experiments performed as described in lanes 3–6 of panel a are summarized; the amount of 32PO4 incorporation into wild type IRAG in the absence of cGMP was assigned a value of 1. Panel c: BHK cells were transfected with pCRE-Luc, pRSV-βgal, and either empty vector or expression vectors encoding wild type or mutant IRAG (S644A) and/or PKG Iβ as indicated. Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of 8-CPT-cGMP and relative luciferase activities were determined as described in Fig. 2a. Panel d: Aliquots of cell extracts from a representative experiment in panel c were analyzed by Western blotting as described in Fig. 2b.

4. DISCUSSION

IRAG is required for cGMP/PKG-mediated inhibition of calcium release from IP3-sensitive stores, and for relaxation of hormone receptor-triggered smooth muscle contraction by PKG [9,30]. Together with the IP3 receptor type I, IRAG is localized to the endoplasmatic reticulum membrane [9]. In cultured, PKG I-deficient smooth muscle cells, defective calcium regulation was rescued by PKG Iα and not Iβ [24,31]; however, smooth muscle-specific expression of either PKG Iα or Iβ rescues PKG I knock-out mice with respect to basic vascular and intestinal smooth muscle function, and both isozymes reduce hormone-induced intracellular calcium levels [32]. Presumably, the effect of PKG Iβ on hormone-induced calcium transients depends on the interaction of PKG Iβ/IRAG with the IP3 receptor I [30].

Co-localization of PKG Iβ with IRAG in the peri-nuclear endoplasmatic reticulum region was observed in transfected COS7 cells [6], and co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous IRAG with PKG Iβ from smooth muscle cells suggests the existence of a stable complex [9]. Our results demonstrate that the interaction between PKG Iβ and IRAG was stable enough to prevent cGMP-induced nuclear translocation of PKG Iβ and impair cGMP/PKG Iβ transactivation of a CRE-dependent reporter gene. The effect required PKG Iβ/IRAG interaction, because nuclear translocation and CRE transactivation by PKG Iα, which does not interact with IRAG, was unaffected, and point mutations that interfere with PKG Iβ binding to IRAG prevented IRAG from inhibiting PKG Iβ transcriptional effects. The inhibitory effect of IRAG on cGMP/PKG Iβ-induced transcription was neither explained by IRAG regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, nor by IRAG competition with PKG phosphorylation of other substrates, because the phosphorylation-deficient, mutant IRAG (S644A) inhibited cGMP/PKG Iβ-induced reporter gene activity to the same extent as wild type IRAG.

In the presence of IRAG, transactivation of the CRE-dependent reporter gene by cGMP/PKG Iβ was reduced, but not absent, even though we could not detect PKG Iβ in the nucleus by immunofluorescence staining. There are at least two possible explanations for this discrepancy: (i) sufficient PKG Iβ translocated to the nucleus to transactivate the reporter gene, but nuclear PKG levels were below the detection limit of immunofluorescence staining; or (ii) transcriptional activation of the CRE-dependent reporter was mediated by cytoplasmic PKG Iβ through activation of other signaling pathways. We favor the first explanation, because we previously showed that mutations in the nuclear localization signal of PKG Iβ prevented nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of the kinase without affecting enzymatic activity [20]. We also demonstrated that cGMP/PKG activation of CRE-dependent transcription is independent of other pathways known to affect CREB activity, such as cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), mitogen-activated protein kinases, or Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases [18,19].

A limitation of the present study is the use of transfected cells, which was necessary to determine the effect of IRAG on PKG Iα and Iβ separately. Expression levels of PKG Iα typically far exceed those of PKG Iβ, even in aortic smooth muscle cells [31], and unfortunately, available PKG Iβ isoform-specific antibodies are not suitable for immunofluorescence studies. However, the present experiments demonstrate that PKG anchoring to a specific binding protein is sufficient to dictate subcellular localization of the kinase and affect cGMP signaling in the nucleus. These studies provide at least one explanation for why nuclear translocation of PKG I is not universally observed, but restricted to certain cell types such as neuronal cells and primary osteoblasts [14,23]. PKG Iα and Iβ-green fluorescent protein fusion constructs are excluded from the nucleus of primary vascular smooth muscle cells, and are rarely detected in the nucleus of HeLa or human embryonal kidney cells [24,25]. We suggest that nuclear translocation of PKG I may depend on the ratio of PKG I isoform expression relative to the expression of specific extra-nuclear PKG I-interaction proteins.

IRAG is expressed at varying levels in a variety of cell types [6], but is likely not the only extra-nuclear PKG I-binding protein that could interfere with nuclear translocation of the kinase. Several PKG I-interacting proteins bind to both PKG Iα and Iβ, such as troponin T, forming homology domain protein-1, and cysteine-rich protein-2 [33–35]. PKG Iα-specific binding proteins include the myosin-binding subunit of myosin phosphatase, the regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS)-2, and vimentin [7,8,36]. Whether or not PKG Iα interaction with these proteins has the same effect on nuclear signaling as the PKG Iβ-specific interaction with IRAG remains to be determined.

The fundamental role of protein/protein interactions in cellular signaling has been most elegantly demonstrated for cAMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). Subcellular compartmentalization of PKA through interactions with different AKAPs provides specificity, and controls the spatio-temporal dynamics of cAMP signaling [37]. AKAP 75 increases the rate and magnitude of cAMP signaling to the nucleus, possibly because it positions the kinase close to the source of cAMP generation, which allows dissociation of the PKA holo-enzyme and nuclear translocation of the free catalytic subunit [38]. Elucidation of the structural requirements for PKA/AKAP interactions has lead to the development of specific anchoring inhibitors, which in turn have demonstrated the functional importance of PKA anchoring in intact cells [39]. Our understanding of PKG anchoring is far less developed, and we are just beginning to elucidate the structural elements that mediate the binding of PKG I isoforms to specific interacting proteins [27].

5. CONCLUSIONS

We have demonstrated that nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of PKG Iβ can be inhibited through expression of the PKG Iβ-interacting protein IRAG, which targets the kinase to the endoplasmatic reticulum. These results may provide an explanation for why nuclear translocation of PKG I occurs in some, but not all cells, and suggest that transcriptional regulation by cGMP depends not only on the abundance of PKG I isoforms, but also on their interaction with specific anchoring proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AR051300 (to R.B.P.); D.E.C. was supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant 5T32-AI007469 (principal investigator: D.H. Broide); and T.Z. was supported by American Heart Association Fellowship Award 0525091Y. We are grateful to Dr. Jim Feramisco for help with deconvolution microscopy at the UCSD Cancer Center Digital Imaging Core Facility.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feil R, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T. Rev Neurosci. 2005;16:23. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2005.16.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lincoln TM, Dey N, Sellak H. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1421. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilz RB, Broderick KE. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1239. doi: 10.2741/1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munzel T, Feil R, Mulsch A, Lohmann SM, Hofmann F, Walter U. Circulation. 2003;108:2172. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094403.78467.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francis SH, Corbin JD. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1999;36:275. doi: 10.1080/10408369991239213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geiselhoringer A, Gaisa M, Hofmann F, Schlossmann J. FEBS Lett. 2004;575:19. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang M, Wang G, Lu P, Karas RH, Aronovitz M, Heximer SP, Kaltenbronn KM, Blumer KJ, Siderovski DP, Zhu Y, Mendelsohn ME. Nature Med. 2003;9:1506. doi: 10.1038/nm958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surks HK, Mochizuki N, Kasai Y, Georgescu SP, Tang KM, Ito M, Lincoln TM, Mendelsohn ME. Science. 1999;286:1583. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlossmann J, Ammendola A, Ashman K, Zong X, Huber A, Neubauer G, Wang G-X, Allescher H-D, Korth M, Wilm M, Hofmann F, Ruth P. Nature. 2000;404:197. doi: 10.1038/35004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casteel DE, Zhuang S, Gudi T, Tang J, Vuica M, Desiderio S, Pilz RB. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ammendola A, Hofmann F, Schlossmann J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peunova N, Enikolopov G. Nature. 1993;364:450. doi: 10.1038/364450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilz RB, Suhasini M, Idriss S, Meinkoth JL, Boss GR. FASEB J. 1995;9:552. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.7.7737465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broderick KE, Zhang T, Rangaswami H, Zeng Y, Zhao X, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Mol Endocrinology. 2007;21:1148. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan SH, Chang KF, Ou CC, Chan JY. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:319. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Fang L, Lin Q, Willis WD. Neuroscience. 2000;96:351. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiang M, Xie J, Wang H, Qiao J. Behav Pharmacol. 1999;10:215. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199903000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudi T, Huvar I, Meinecke M, Lohmann SM, Boss GR, Pilz RB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gudi T, Casteel DE, Vinson C, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Oncogene. 2000;19:6324. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gudi T, Lohmann SM, Pilz RB. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5244. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gudi T, Vaandrager AB, Lohmann SM, Pilz RB. FASEB J. 1999;13:2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyatt TA, Lincoln TM, Pryzwansky KB. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Bruderer S, Rafi Z, Xue J, Milburn PJ, Krämer A, Robinson PJ. EMBO J. 1999;18:4549. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.16.4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feil R, Gappa N, Rutz M, Schlossmann J, Rose CR, Konnerth A, Brummer S, Kuhbandner S, Hofmann F. Circ Res. 2002;90:1080. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000019586.95768.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browning DD, McCMarty SM, Ye RD. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins SP, Uhler MD. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casteel DE, Boss GR, Pilz RB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koller A, Schlossmann J, Ashman K, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Ruth P, Hofmann F. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2003;300:155. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayr B, Montminy M. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geiselhoringer A, Werner M, Sigl K, Smital P, Worner R, Acheo L, Stieber J, Weinmeister P, Feil R, Feil S, Wegener J, Hofmann F, Schlossmann J. EMBO J. 2004;23:4222. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen EN, Mendelsohn ME. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512770200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber S, Bernhard D, Lukowski R, Weinmeister P, Worner R, Wegener JW, Valtcheva N, Feil S, Schlossmann J, Hofmann F, Feil R. Circ Res. 2007 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuasa K, Michibata H, Omori K, Yanaka N. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y, El-Zaru MR, Surks HK, Mendelsohn ME. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huber A, Neuhuber WL, Klugbauer N, Ruth P, Allescher H-D. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacMillan-Crow LA, Lincoln TM. Biochemistry. 1994;33:8035. doi: 10.1021/bi00192a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beene DL, Scott JD. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:192. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassano S, Gallo A, Buccigrossi V, Porcellini A, Cerillo R, Gottesman ME, Avvedimento EV. J Biol Chem. 1996;47:29870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colledge M, Scott JD. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:216. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01558-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.