Abstract

PURPOSE Clinicians often have an intuitive understanding of how their relationships with patients foster healing. Yet we know little empirically about the experience of healing and how it occurs between clinicians and patients. Our purpose was to create a model that identifies how healing relationships are developed and maintained.

METHODS Primary care clinicians were purposefully selected as exemplar healers. Patients were selected by these clinicians as having experienced healing relationships. In-depth interviews, designed to elicit stories of healing relationships, were conducted with patients and clinicians separately. A multidisciplinary team analyzed the interviews using an iterative process, leading to the development of case studies for each clinician-patient dyad. A comparative analysis across dyads was conducted to identify common components of healing relationships

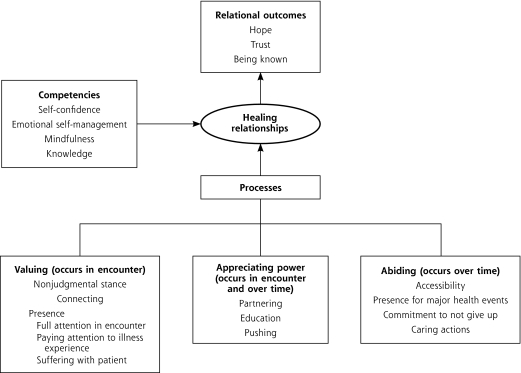

RESULTS Three key processes emerged as fostering healing relationships: (1) valuing/creating a nonjudgmental emotional bond; (2) appreciating power/consciously managing clinician power in ways that would most benefit the patient; and (3) abiding/displaying a commitment to caring for patients over time. Three relational outcomes result from these processes: trust, hope, and a sense of being known. Clinician competencies that facilitate these processes are self-confidence, emotional self-management, mindfulness, and knowledge.

CONCLUSIONS Healing relationships have an underlying structure and lead to important patient-centered outcomes. This conceptual model of clinician-patient healing relationships may be generalizable to other kinds of healing relationships.

Keywords: Physician-patient relations, communication, primary health care, healing

INTRODUCTION

Wild azaleas bloom in my garden every spring, reminding me of the botanist who gave them to me and our journey through his suffering and eventual death from prostate cancer. During this relationship and others like it I (J.G.S.) came to understand the powerful healing connections forged between doctor and patient. I realized the quality of the relationships I created with patients was as important as the pills I dispensed, and that relationships with patients sustained me through the difficult and sometimes frustrating tasks of practicing family medicine. Although many physicians have an intuitive understanding of the importance of healing relationships, there are few systematic studies in the medical literature that empirically examine what healing relationships might look like and how they are built by clinician and patient.1

Research in other disciplines shows the importance of healing relationships. Anthropologists have explored healing as a cross-cultural phenomenon and distinguished categories related to healing.2 In psychotherapy, research finds that the nature of the therapist-client relationship accounts for approximately 45% of the effectiveness of therapy.3 Nurses have carried out research on healing for many years. Although there has been considerable theoretical development in this literature, most empirical work has focused on interviews with nurses.4 Patient interview studies have focused on particular aspects of the nurse-patient relationship, especially caring.5

Most of the existing theoretical models of healing relationships are based on interviews with health care professionals or patients, but not both.4–6 Using a grounded theory approach, my fellow authors and I interviewed clinicians and their patients to depict how healing relationships are created, structured, and maintained.

METHODS

This study was designed to explore healing in the context of ongoing clinician-patient relationships in which healing was recognized by the clinician. We realize that there may be many other situations in which healing occurs that are not connected to clinician-patient relationships,7 and that healing may occur in the context of clinician-patient relationships without the clinician’s knowledge. We focused on healing in clinician-patient relationships because of its potential to change and improve clinician behavior and facilitate the development of the “continuous healing relationships” recommended by the Institute of Medicine’s report on quality of care.8

Sampling Strategy

To enhance the probability of observing the phenomenon under study, it was necessary to choose physicians who were most likely to create healing relationships with patients. Physicians believed to be exemplars in developing and maintaining healing relationships were purposefully selected based on an assessment of publications, reputation, and awards. In addition, we recognized that even exemplar clinicians would not have healing relationships with all their patients, and the phenomenon we wanted to explore required that clinicians be aware healing had emerged in the context of their relationship with patients. For these reasons, each clinician was asked to choose adult patients who they perceived had experienced healing. Healing was purposely left undefined to allow the definition to emerge from the participants’ experiences. Sampling proceeded iteratively, with analysis of each interview informing and refining the interview guide and the interview process for subsequent interviews. Interviews continued until the analysis team determined that saturation had been reached.

Interviews

To minimize analysis complexities associated with differing world views and experiences of multiple qualitative interviewers, the analysis team decided that the first author should conduct all interviews. The potential bias introduced by having a single physician interviewer was managed as follows. Before conducting the study interviews, the first author interviewed 5 of his former patients to increase his own and the analysis team’s awareness of his experience as a clinician and healer; to allow him to discuss, analyze, and gain a greater awareness of his personal beliefs about healing; and then to manage and control these preconceptions, as best as possible, during interviews.9 The physician’s ideas about healing and the nature of healing relationships were recorded in a journal format, and self-reflective field notes were dictated after each interview. The analysis team reviewed all of this material. In addition, the analysis team critiqued each interview, particularly during the early interviews, pointing out to the interviewer questions and approaches that revealed preconceptions, as well as physician-centric biases.

After obtaining informed consent, the first author conducted face-to-face in-depth interviews separately with each physician and patient according to a semi-structured interview guide (Supplemental Appendixes 1 and 2, available online-only at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/6/4/315/DC1) that contained several grand tour questions10 designed to elicit healing stories from physicians and patients. Additional questions examined physicians’ role as healers in the context of the ongoing relationship with patients and the effect of relationships on healing processes. Interviews lasted 1 to 2 hours.

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Physician D5 invited the spouses of 3 of his patients to be present during the interviews. Although asking a spouse to be present was not part of the original study design, the interviewer chose to view it as an opportunity to observe how such an arrangement might influence accounts of healing experiences. The analysis team, however, found no substantive differences in the content of interviews when spouses were present compared with interviews with patients alone. Transcripts were checked for accuracy. Digital voice files and transcripts were imported into qualitative analysis software, Atlas ti.11 The Robert Wood Johnson Medical School Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Analysis

The analysis team consisted of a family physician with 21 years’ experience in private practice (J.G.S.), a medical anthropologist with years of experience in primary care research (B.F.C.), a nurse who had extensive experience in home and hospice care (B.D.B.), and a specialist in communication science with expertise in qualitative methods (D.C.).

Interviewing and analysis proceeded iteratively.12 As transcripts became available, the analysis team listened to and discussed interviews as a group. After the group had listened to a number of interviews, common issues or themes began to emerge. The group discussed these themes, making our understanding of them richer and deciding how insights would guide subsequent data collection. Data collection and preliminary analysis continued in this fashion until saturation was reached. Saturation occurred after interviewing 5 physicians and 23 patients.12

The first author used an open coding process13 to tag data excerpts the group identified as interesting. The analysis team read and reread these excerpts in the context of the larger interview to construct case studies describing the nature of the relationship of the clinician-patient dyad. Insights were discussed, refined, and developed into a coherent case study of each physician and all of his/her patients. Case studies were analyzed across physicians to identify common themes and to develop a preliminary model of healing relationships.

Although patients’ comments about the study clinicians were uniformly positive, patients made numerous negative comments about other clinicians. These negative comments served as a contrast to highlight what participants took to be components of healing. Because of space limitations we report only the components of healing, but we examined these contrastive comments in depth in our analysis and in our construction of the conceptual model.

Two authors (W.L.M. and K.C.S.) who were unfamiliar with the details of the team’s preliminary analysis helped refine the model during 2, 2-day retreats. Finally, the analysis team performed member checking9 by soliciting feedback on the model from 2 physician interviewees.

RESULTS

Sample Demographics

Demographic characteristics of participating physicians and their practices (Table 1 ▶) and their patients (Table 2 ▶) are shown below. Although it was not a requirement for participation in this study, most physicians selected patients who had either current or chronic illnesses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, ischemic heart disease, chronic pain syndrome, recurrent pulmonary emboli, diabetes, valvular heart disease, history of sexual abuse, history of drug abuse, and breast cancer.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Physicians Interviewed

| Physician | Sex | Practice Type | Population | Years in Current Practice | Patients Interviewed |

| D1 | Male | Academic | Urban, high socioeconomic status | 10 | 2 |

| D2 | Male | Solo with nurse-practitioner | Indigent inner-city, mostly Hispanic | 15 | 4 |

| D3 | Male | Group practice with 5 physicians | Suburban | 20 | 3 |

| D4 | Female | Large community health center | Mostly indigent inner-city | 31 | 4 |

| D5 | Male | Group practice with 4 physicians | Small-town, white, mostly blue collar | 21 | 5 |

| D6 (author) | Male | Group practice with 4 physicians | Small-town, mostly white, mixed socioeconomic status | 21 | 5 |

Table 2.

Patient (N = 23) Demographics

| Category | No. of Patients |

| Age, years | |

| Mean | 58.2 |

| Range | 30–86 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 |

| Female | 14 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 17 |

| Black | 2 |

| Hispanic | 4 |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Low | 5 |

| Mid | 4 |

| High | 14 |

Model of Healing Relationships

The components of the model are described in Table 3 ▶ and depicted in Figure 1 ▶. Although length considerations prohibit inclusion of extensive quotations, we convey a flavor of the richness of the interviews through brief data excerpts.

Table 3.

Healing Model Components

| Model Component | Definitions |

| Healing processes | |

| Valuing | |

| Nonjudgmental stance | Accepting every patient as a person of worth |

| Connecting | Finding personal resonance with each particular patient |

| Presence | Being mindfully present when with the patient |

| Full attention in encounter | Actively listening to patient’s story |

| Acceptance of illness experience | Recognizing importance of patients’ subjective experience of illness |

| Empathy | Connecting patient’s experience of suffering with healer’s life experience |

| Appreciating power | |

| Partnering | Engaging patients as partners in decisions about diagnosis and treatment |

| Education | Explanation of medical jargon and teaching patients self-management |

| Pushing | Using healer power for patient benefit |

| Abiding | |

| Interpersonal continuity | Ability for patient to see same healer over time, most of the time |

| Major health crises | Caring for patients during significant health events |

| Caring actions | Accumulation of actions that allow patients to know that the healer cares |

| Not giving up | Trying to reduce patient suffering even when science has nothing left to offer |

| Healer competencies | |

| Self-confidence | Projection of confidence in healer’s ability to heal |

| Emotional self management | Appropriately recognizing and managing emotions |

| Mindfulness | Ability to be aware in the moment of internal and external environment |

| Knowledge | Store of information about diagnosis and treatment |

| Relational outcomes | |

| Trust | Willingness to be vulnerable, feeling cared for, kowing promises will be kept |

| Hope | Belief that some positive future beyond present suffering is possible |

| Being known | Accumulated sense that the physician knows the patient as a person. |

Figure 1.

Healing relationship model.

Processes of Healing Relationships

Valuing

Valuing begins with a conscious attempt by clinicians to be nonjudgmental by approaching all patients as persons of worth. As one patient said of her physician, “…everybody who walks in front of her is the same.… She doesn’t care what kind of insurance you have, what color you are, how big you are, how small you are.”

Clinicians also reported attempting to form connections with patients, looking for shared experiences that resonate within the life experience of both the clinician and patient. One physician described this process as, “I try to love every single patient. And I especially try to love those I initially hate. There has to be some reason why I want them to get better.” Through these connections, patients reported clinicians care about them as people, not just as containers for disease. As one patient said, “So, you feel like you’re not just patient No. 123 or something, so it’s human medicine…. So, it’s nice to look at you as a whole person with a mind and body together.”

A third aspect of valuing is presence—giving full attention to patients. As one patient reported, “…she is totally directed and focused on you when she is with you.… This is your time.” When patients felt clinician presence, regardless of the actual time spent in the encounter, patients reported feeling unrushed. As one patient said, “Well he sat there and he listened. And he never rushed you out of the office. You took as long as you needed.” This patient’s physician, for whom time management was very important (averaging 15 minutes per encounter), said, “All the time they need is really the time it takes to hear their problem clearly and respond to it earnestly and to be sure that you are responding to their problem and not your problem.” In addition, being present allows the clinician to participate in the patient’s story of suffering. The same physician described this as “dwelling for a moment in their pain, in their misery, not letting it float off our backs.”

Appreciating Power

Clinicians in our sample reported that most often they work to increase patients’ power. One way they do this is by engaging patients as partners. As one patient stated, “one thing I really appreciated with [my doctor] is like we’re a partnership.” Another way of managing power is to educate patients by translating medical jargon into language patients understand and by providing patients with the knowledge needed to manage their own illnesses. For example, a patient said of her doctor, “He explained what I needed to do going forward, the life change it would take, you know the medication, the eating habits, and everything to try and keep it from happening again.”

Sometimes, however, clinicians carefully pushed resistant patients to take actions that were important for their health. According to one patient infected with HIV, “…that’s why I really need, someone to push me, tell me you have to do those things. That’s one of the reasons that I’m still here.” Exemplar clinicians described an intuitive understanding about when and how to push patients based on assessments of patients’ needs and strength of relationships. One physician described it this way: “…some-times you’re the coach and sometimes you’re the boss and sometimes you’re the sibling and sometimes you’re the doctor.”

Abiding

One common characteristic of clinicians in this study is the stability of their practices; they have been in one location for many years. This stability fostered personal continuity. Personal continuity led to a degree of intimacy that both clinicians and patients likened to relationships between members of a family. As one patient said, “And I think after years and years and years and years it’s like…a marriage. You and your doctor has a marriage.” This experience of working together, particularly through major health events, contributed to the development of a history between clinician and patient that enriched and deepened the therapeutic relationship. As one physician said, “There’s being there for the big events, whether that’s birth or death or the diagnosis of something bad, or being there when they need you to be there, pushing other things away in order to be there in a way that’s more substantial.”

Clinicians’ commitment to patients was cumulative and expressed through caring actions. Some actions went beyond the requirements of the doctor-patient relationship (eg, home visits, telephoning patients after hours, taking time to research answers to patient questions, helping patients navigate complex bureaucracies). Other caring actions were the day-to-day little things in clinical practice that showed clinicians’ respect for patients. For example, one physician said, “I also do those things that most doctors find other people to do. I trim toenails. I irrigate ears. I take off little ditsils from the skin. I draw blood.” This caring and commitment communicated through physicians’ actions—both large and small—implies a promise to not abandon the patient, even if pills and technology have little left to offer. “Yeah, but he never gave up on me. And that means a lot,” said one patient.

Competencies Supporting Healing Relationship Processes

A projection of self-confidence by clinicians was important to patients. For example, one patient said “there was a certain amount of confidence, I think, about her. And she exuded confidence to the patient.”

Emotional self-management requires clinicians to recognize and manage their own emotions so that they project calmness calibrated to the emotional state of patients. “Maintaining a calm, this-is-okay demeanor I think has saved that child innumerable visits to the emergency room and unnecessary tests and treatments,” said one physician.

Mindfulness, a constant awareness of the encounter at multiple levels, is illustrated by the following quote from a physician: “Is this a story of shame and they need you to listen? Is this a story of fear and they need you to be there with them? Is this a story of blame…or self-blame and they need to hear that it wasn’t their fault? I mean, what is the story? So what role do they need you to be in?”

Clinical knowledge was also important to patients. As one patient said, “…it’s just your skill, your knowledge. I’m not about to go to a crackpot.” Clinicians are seen as more knowledgeable if patients perceive that they know their own limitations and display a willingness to seek assistance when those limits are reached. One patient stated it this way: “I think to admit when you don’t know something. You’re human. Wow!”

Relational Outcomes

The processes of healing relationships lead to 3 relational outcomes necessary for healing to occur.

Trust emerges from the processes of valuing and abiding in the relationship with time. As one physician said, “…the word is trust that you build up over time. That’s something that you can’t do right away. You have to sort of earn that.” Earning trust does not mean that trusted clinicians never make mistakes. In fact, admission of occasional mistakes may actually enhance patient trust; as one patient states, “…he had the courage to say, ‘Well, I made a mistake.’ That endeared him to me forever.”

Hope as an outcome is described by one physician as follows:

And this act of connecting, these connections, I regard as hope…I realize that I can’t create hope for patients. It has to be there or it’s not. But I can certainly point out to them the places where they can look.… I can insist that they look for areas where they’re likely to find their own hopefulness. And if that hopefulness is not to recover from esophageal or pancreatic cancer, maybe it’s simply to hope to have a few good days remaining, hope to touch base with those they’ve been distant from, hope to find gratitude in the life they’ve been given.

Patients want clinicians to help them define honest and realistic expectations, differentiating among clinicians who attend to this effort in an emotionally connected way from those who do so in a dispassionate, disconnected fashion. One patient noted, “I think that some doctors tend to, like, be gloom and doom, and some doctors try to give it and not look so bad. I think, you know, you can say the same things two ways.” These patients viewed unrealistic optimism, however, as deliberate deception. “I don’t ever want anybody to try to put anything over on me health-wise,” said one patient. At the same time, the inherent uncertainty of outcomes for any individual leaves room for the possibility that a particular patient may experience something different from usual outcomes. As one patient reflected, “But I think hope is that little glimmer out there that there are new medicines.”

Another aspect of hope is expectancy or belief. For example, one patient mentioned, “He gets you feeling better even without the medication. You just have that feeling that you’re going to feel better after you see him.”

A feeling of being known is another relational outcome that emerged through the processes of valuing and abiding. Patient and clinician shared a history, and as a result patients felt known as individuals. One patient noted, “…she knows who I am first of all. She knows exactly who I am. She knows my thoughts and my way of understanding things.”

DISCUSSION

The interviews showed that both patients and clinicians had a common understanding of the nature of healing. Healing meant being cured when possible, reducing suffering when cure was not possible, and finding meaning beyond the illness experience. This finding bears a striking resemblance to Egnew’s definition of healing as “transcendence of suffering.”6 We found the locus of healing neither in patient nor in healer, but rather in the space created by connections of the two, what philosopher William Desmond terms “The Between.”14

Although we designed the interviews to explore healing relationships between physicians and patients, we also included questions about other healing relationships. Not surprisingly, patients had many healing relationships, only one of which was with their physician. We found that the attributes of these relationships were very similar to those of clinician-patient relationships. Thus the model we propose may apply to a range of healing relationships.

Healing has been studied extensively, and our study findings are consistent with what others identify as conceptual components of healing relationships. Jackson, in a review of the nursing literature on healing, describes healing relationships as “a true sharing of self,” and nursing research has emphasized connection and caring as essential to the healing process.4 The relationship-centered care model, as delineated by the Pew-Fetzer Task Force Report includes many components that are similar to our findings, including self-awareness, appreciation of the patient as a whole person, importance of being nonjudgmental, attending fully to the patient, understanding power inequalities, and facilitating hope trust and faith.15 Healing relationships have also been studied in the anthropology2 and psychotherapy16 literature. This study extends this literature by looking at healing in the context of the clinician-patient relationship rather than from a single vantage point, and, as such, develops a relational model of healing and one that is based in empirical data and the experiences of participants.

Of what use are healing relationships in the current world of evidence-based medicine? This question can be answered on 3 levels. First, our data suggest that healing relationships with clinicians and others improve the quality of patients’ lives. Hope, trust, and being known are outcomes of healing relationships that are important to patients and should be important to doctors as well. Second, ample evidence shows that certain aspects of relationships in general, and of clinician-patient relationships in particular, are related to morbidity,17 mortality,18 treatment adherence,19 health status,20 and clinical outcomes, such as for diabetes.21 Belief and expectancy, which we have included under the broader heading of hope, are strongly connected to response to treatment.22 Third, healing relationships seemed to work in both directions. The clinicians in this study have been in practice, some in very difficult environments, for 15 to 30 years and still greatly enjoy what they do. Their experience stands in sharp contrast to the low morale and high burnout among primary care physicians documented in recent literature.23–25

Because we studied unusual clinicians, one might argue that these results have little relevance for the average practicing clinician. The clinicians in our study, however, functioned under the same financial constraints, time pressures, patient volume requirements, and paperwork burden as do most other primary care clinicians in the northeast. One might also argue that every clinician has patients with whom they have a special connection, and that the patients in our study are not representative of all of the patients of our study clinicians. Clearly, most patients who come to the doctor for preventive care or acute illness do not feel the need for a healing relationship at that time, yet illness and suffering await all of us sooner or later. The patients in this study, most of whom had chronic illnesses, needed and were able to co-construct healing interactions with their doctors. Because of the study design, we cannot be sure that other equally needy patients of these physicians experienced that same kind of relationship, but clinician interviews suggest attempts were made to create healing relationships with all patients who were in need.

Another possible concern is that the intimate relationships we describe might interfere with the detached concern required for the best diagnosis and treatment, what William Osler called “Equanimitas.”26 Although our study was not designed to provide a systematic answer to this concern, there was no evidence in the content of clinician or patient interviews to suggest that patients received substandard medical care. Furthermore, there is some evidence that constructing the kind of relationships we describe may lead to more accurate diagnoses and better treatment.27,28 Finally, healing relationships gave meaning, joy, and satisfaction to both physicians and patients, suggesting that the solution to problems of physician burnout and patient frustration with medical care may lie not only in improving systems or changing reimbursement, but also in fostering healing relationships.

There are limitations to our analysis. The clinicians and patients in this study were purposefully chosen as exemplars, and, as such, are not likely to be representative of primary care clinician-patient relationships in general. Our model, therefore, may represent a goal to strive for rather than a description of current practice. It is possible that the nature of clinician-patient healing relationships is affected by the sex, race, and ethnicity of both patients and clinicians. In our small sample we noted no such effect, but our sample was chosen to maximize the probability that the phenomenon we wanted to study would be present, and our findings cannot be used to generalize about the effects of sex, race, and ethnicity. We are currently developing a survey instrument based on the model, which will be able to address questions of generalizability. Interview data have the inherent limitation of dealing with perceptions of respondents’ experiences of events rather than observations of events themselves. A longitudinal study using direct observation of clinician-patient encounters could make the proposed model operational and expand it. Our interpretation of these data is influenced by our life experience. Others might view the data differently and come to different conclusions. The validity of our analysis, however, is enhanced by the diversity of training and experience of the analysis team, use of different data sources (clinicians and patients), reflexivity (reflecting on our own experiences), external independent auditing, and member checking (having participants review our conclusions).29

In conclusion, clinician-patient healing relationships have discernible structure and lead to important patient-centered outcomes. This conceptual model of clinician-patient healing relationships may be generalizable to other kinds of healing relationships.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lucy Candib, MD, and David Loxterkamp, MD, for their careful reading and constructive suggestions regarding this manuscript. We also express our gratitude to the patients and clinicians who shared their stories of healing with us.

Conflicts of interest: Drs. Scott and DiCicco-Bloom report no conflicts of interest. Drs Stange, Cohen, and Miller are members of the Annals of Family Medicine editorial team and were blocked from all parts of the peer review and editorial decision-making process on this manuscript.

Funding support: This study was funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars program to Dr Scott, an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professorship Grant to Dr Stange, and a Family Medicine Research Center Grant from the American Academy of Family Physicians.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Duffy MB, Epstein RM, Stange KC. Research guidelines for assessing the impact of healing relationships in clinical medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(3)(Suppl):A80–A95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Csordas TJ, Kleinman A. The therapeutic process. In: Johnson TM, Sargent CF, eds. Medical Anthropology: Contemporary Theory and Method. New York, NY: Praeger Publishers; 1990.

- 3.Lambert MJ. Implications of outcome research for psychotherapy integration. In: Norcross JC, Goldstein MR, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy Integration. New York, NY: Basic Book; 1992:94–129.

- 4.Jackson C. Healing ourselves, healing others: first in a series. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18(2):67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson K. What is known about caring in nursing science: a literary meta-analysis. In: Hinshaw AS, Feetham S, Shaver JLF, eds. Handbook of Clinical Nursing Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999:31–60.

- 6.Egnew TR. The meaning of healing: transcending suffering. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Healing landscapes: patients, relationships, and creating optimal healing places. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S41–S49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm. A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- 9.Malterud K. Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet. 2001;358(9280):483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCracken GD. The Long Interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988.

- 11.Atlas.ti [computer program]. Version 5. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development; 2003–2005.

- 12.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992.

- 13.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

- 14.Desmond W. Being and the Between. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1995.

- 15.Tresolini C, and The Pew-Fetzer Task Force. Health Professions Education and Relationship Centered Care. San Francisco, CA: Pew Health Professions Commision; 1994.

- 16.Hubble ML, Duncan BL, Miller SD. The Heart and Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999.

- 17.Krumholz HM, Butler J, Miller J, et al. Prognostic importance of emotional support for elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 1998;97(10):958–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammadi E, Abedi HA, Jalali F, Gofranipour F, Kazemnejad A. Evaluation of ‘partnership care model’ in the control of hypertension. Int J Nurs Pract. 2006;12(3):153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE Jr. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27(3)(Suppl):S110–S127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts AH, Kewman DG, Mercier L, Hovell M. The power of nonspecific effects in healing—implications for pyschosocial and biological treatments. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13(5):375–391. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geyman JP. Health Care in America: Can Our Ailing System be Healed? Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002.

- 24.Reed M, Ginsburg P. Behind the times: physician income, 1995–1999. Data Bulletin No.24. HSC Research Number 24. CSHSC Web site. http://hschange.org/CONTENT/544/. Accessed Jul 23, 2005.

- 25.Ruhe M, Gotler RS, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Physician and staff turnover in community primary care practice. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27(3):242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osler W. Aequanimitas. Philadelphia, PA: Blakiston’s Son & Co; 1906.

- 27.Epstein RM. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282(9):833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groopman JE. How Doctors Think. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2007.

- 29.Malterud K. The art and science of clinical knowledge: evidence beyond measures and numbers. Lancet. 2001;358(9279):397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]