Abstract

PURPOSE We wanted to examine whether integrating depression treatment into care for hypertension improved adherence to antidepressant and antihypertensive medications, depression outcomes, and blood pressure control among older primary care patients.

METHODS Older adults prescribed pharmacotherapy for depression and hypertension from physicians at a large primary care practice in West Philadelphia were randomly assigned to an integrated care intervention or usual care. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess depression, an electronic monitor to measure blood pressure, and the Medication Event Monitoring System to assess adherence.

RESULTS In all, 64 participants aged 50 to 80 years participated. Participants in the integrated care intervention had fewer depressive symptoms (CES-D mean scores, intervention 9.9 vs usual care 19.3; P <.01), lower systolic blood pressure (intervention 127.3 mm Hg vs usual care 141.3 mm Hg; P <.01), and lower diastolic blood pressure (intervention 75.8 mm Hg vs usual care 85.0 mm Hg; P <.01) compared with participants in the usual care group at 6 weeks. Compared with the usual care group, the proportion of participants in the intervention group who had 80% or greater adherence to an antidepressant medication (intervention 71.9% vs usual care 31.3%; P <.01) and to an antihypertensive medication (intervention 78.1% vs usual care 31.3%; P <.001) was greater at 6 weeks.

CONCLUSION A pilot, randomized controlled trial integrating depression and hypertension treatment was successful in improving patient outcomes. Integrated interventions may be more feasible and effective in real-world practices, where there are competing demands for limited resources.

Keywords: Adherence, medication therapy management, hypertension, depression, primary health care, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Primary care occupies a strategic position in the evaluation and treatment of depression among older adults,1 and enhancing depression management in primary care appears to be a promising use of health care resources.2 To have an impact on public health, advances in the treatment of depression must be realized in primary care. Although recent studies have shown that a variety of primary care interventions can improve depression outcomes among older adults,3,4 these interventions are not being widely implemented in practice. Some evidence indicates that addressing medical comorbidity, especially cardiovascular disease (CVD), may be essential in managing depression.5–7 In addition, managing depression in the context of medical comorbidity may be more acceptable to patients than managing depression alone.8 Despite these findings, no known trials have been conducted in primary care integrating the management of depression with management of medical comorbidity.

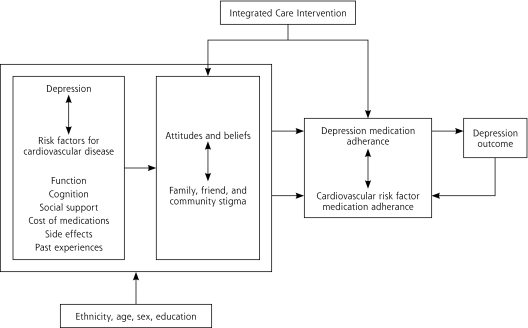

In this trial, we focused on integrating depression management into care for hypertension. Hypertension affects between 20% to 50% of adults in most countries9 and is a major risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,10 representing two-thirds of all strokes and one-half of all ischemic heart disease.11 Depression is a risk factor for hypertension,12 and it is associated with poor adherence to antihypertensive medications.13 We chose an adherence-based approach because, although efficacious pharmacotherapy for many chronic medical conditions exists, many patients are not adherent to treatment and are therefore at increased risk for a variety of complications.14 Poor adherence to treatment remains a serious impediment to improving care.15,16 Our conceptual framework, adapted from Cooper and colleagues,17 is practical in its approach and provided a framework that allowed for flexible, tailored interventions (Figure 1 ▶). Our intervention addressed each factor resulting in nonadherence in the conceptual model by means of a multifaceted, individualized approach in which participants worked with the integrated care manager to develop strategies to overcome barriers to adherence to medications.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework adapted from Cooper et al.17

We hypothesized that in a sample of older primary care patients with depression and hypertension, patients who were randomized to receive the intervention compared with usual care would have the following outcomes after a 4-week period: (1) fewer depressive symptoms, (2) lower systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure, (3) a greater proportion with 80% or greater adherence to an antidepressant medication, and (4) a greater proportion with 80% or greater adherence to an antihypertensive medication.

The research protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave written informed consent.

METHODS

Recruitment Procedures

Patients were recruited from a community-based primary care practice in West Philadelphia with 12 family physicians. More than 30,000 patient visits occur each year at the practice. From December 2005 to August 2006, depressed older adults with hypertension and upcoming appointments were recruited into the study. Patients were initially identified through an electronic medical record with the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 50 years and older; (2) a systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or greater or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or greater for nondiabetic patients, or a systolic blood pressure of 130 mm Hg or greater or a diastolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg or greater for patients with diabetes on at least 2 visits in the previous year, or a prescription for an antihypertensive medication within the past year; and (3) a diagnosis of depression or a prescription for an antidepressant medication within the past year.

In all, 109 patients identified by electronic medical records as potentially eligible were approached for further screening. Of those approached, 73 (67.0%) provided oral consent for screening. At the baseline visit, to be eligible for the study, patients had to meet the entry criteria for the study. To enroll as many older persons as possible who were willing and able to participate, we included participants with a range of depressive symptoms reflecting the concept of the relapsing, remitting nature of depression in primary care.18 Nine patients were excluded: 4 were cognitively impaired, 2 were unable to communicate in English, 2 resided in a care facility that provides medications on a schedule, and 1 was unable to use Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) caps (AARDEX, Zug, Switzerland), which are microelectionic monitoring devices. The remaining 64 eligible patients completed enrollment procedures and were randomly assigned to an integrated care intervention (n = 32) or to usual care (n = 32).

Intervention

Integrated care can be defined as a set of techniques and organizational models to create connectivity, alignment, and collaboration within and between the cure and care sectors at the funding, administrative, and/or clinician levels.19 The goals of integrated care are to enhance quality of care and quality of life, consumer satisfaction, and system efficiency for patients with complex problems, cutting across multiple sectors and clinicians.20,21 Relying on this framework, we carried out an integrated care intervention to promote patients’ adherence to antihypertensive and antidepressant treatment. Our study differed from other studies by focusing on the integrated care manager’s unique role as an intermediary or liaison between the physician and the elderly depressed patient with hypertension. The integrated care manager collaborated with physicians to help participating patients recognize depression in the context of hypertension, offered the patients guideline-based treatment recommendations, monitored the patients’ treatment adherence and clinical status, and provided appropriate follow-up. The key components of this integrated care intervention were (1) providing the patient with an individualized program that is congruent with patients’ social and cultural context; and (2) integrating depression treatment with hypertension management.

The integrated care manager worked individually with patients to address the factors involved in adherence as displayed in our conceptual model (Figure 1 ▶). Through in-person sessions and telephone conversations, the integrated care manager provided education about depression and hypertension, emphasizing the importance of controlling depression to manage hypertension; offered encouragement and relief from stigma; helped to identify target symptoms for both conditions; explained the rationale for antidepressant and antihypertensive medication usage; assessed for side-effects and assisted in their management; assessed progress (eg, reduction in depressive symptoms); assisted with referrals; and monitored and responded to life-threatening symptoms (eg, chest pain, suicidality). The intervention was offered to patients as a supplement to, rather than a replacement for, existing primary care treatment. We chose this multifaceted approach because education alone has not been found to be effective for improving adherence.22

The intervention consisted of 3, 30-minute in-person sessions and 2, 15-minute telephone-monitoring contacts during a 4-week period. A master’s level research coordinator was trained as an integrated care manager and administered all study activities. Before the trial started, the integrated care manager received training on pharmacotherapy for depression and hypertension management during weekly clinical sessions with the principal investigator. While under the supervision of the principal investigator, the integrated care manager conducted mock study activities with 2 participants and thereafter received ongoing weekly supervision for all study activities, with the principal investigator monitoring 25% of weekly sessions to ensure the integrated care manager adhered to study protocols.

Usual Care

At baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks, usual care participants underwent the same assessments as participants in the integrated care intervention. Assessments were conducted in person (as were assessments in the integrated care intervention). The principal investigator randomly monitored 25% of sessions weekly to ensure that there was no carryover of the intervention into the usual care group.

Measurement Strategy

To screen potential participants, we used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) to assess for mania or hypomania, psychotic syndrome, alcohol abuse or dependence, and acutely suicidal or psychotic thoughts,23 and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), a short standardized mental status examination,24 to evaluate cognitive impairment (defined as a MMSE score of less than 21).25 We asked patients whether they resided in a care facility that provided their medications on a schedule and whether they were unwilling or unable to use the MEMS caps.

At baseline sociodemographic characteristics were assessed using standard questions. We measured patients’ functional status using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36).26,27 Depression, blood pressure, and adherence were measured at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to measure depression. This scale was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health and has been used widely in research among the elderly.28,29 Patients’ blood pressure was assessed in accordance with American Heart Association Guidelines30 using the BpTRU (BpTRU Medical Devices, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada), an automated device that is designed for clinical settings and avoids observer bias. Unlike the traditional mercury technique, the BpTRU is an oscillometric monitor that takes 6 consecutive blood pressure readings, drops the first reading, and averages the remaining 5. Adherence to antidepressant and antihypertensive medications was measured using electronic-monitoring data obtained from MEMS caps.

Analytic Strategy

We compared characteristics of participants at baseline using the t test and Fisher’s exact test (for continuous or categorical variables as appropriate). In addition, characteristics of patients who refused to participate in the study were compared with those who participated using t tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Blood pressure and depressive symptoms were compared between the intervention group and usual care groups using t tests at 6 weeks. Adherence was defined as the percentage of prescribed doses taken and was calculated as the number of doses taken divided by the number of doses prescribed during the observation period multiplied by 100%. Because the proportion of pills taken was highly skewed and failed normality assumptions, adherence was dichotomized at a threshold of 80%, a level used to assess adherence to medication regimens.31 We used Fisher’s exact test to compare the proportions of participants who were adherent to antidepressant and antihypertensive medications in the intervention group and the usual care group at 6 weeks. Analysis was conducted using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Ilinois). We set statistical significance at α = .05, recognizing that tests of statistical significance are approximations and serve as aids to interpretation and inference.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Participants ranged from age 50 to 80 years, with an average age of 58.6 years (SD = 6.8 years). Forty-nine (76.6%) of the 64 participants were women. Fifty-two (81.2%) participants self-identified as African-American, 11 (17.2%) self-identified as white, and 1 (1.6%) self-identified as “other.” Characteristics of the integrated care participants did not differ significantly from those of the usual care participants (Table 1 ▶). There were no statistically significant differences in characteristics when comparing patients who agreed to participate in the study with those who did not. All participants attended the required sessions at baseline, 2, 4, and 6 weeks and continued to receive regular care from their primary care physician and other medical specialists.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

| Characteristic | Usual Care (n=32) | Intervention (n=32) | PValue |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Age, mean y (SD) | 57.5 (6.3) | 59.7 (7.3) | .20 |

| Ethnicity, African American, n (%) | 28 (87.5) | 25 (78.1) | .35 |

| Sex, women, n (%) | 25 (78.1) | 24 (75.0) | .50 |

| Less than high school education, n (%) | 9 (28.1) | 6 (18.8) | .28 |

| Lives alone, n (%) | 10 (31.3) | 15 (46.9) | .15 |

| SF-36 scores | |||

| Physical function score, mean (SD) | 64.5 (34.9) | 54.1 (33.2) | .22 |

| Social function score, mean (SD) | 83.8 (33.5) | 75.6 (37.6) | .37 |

| Role physical score, mean (SD) | 65.6 (42.5) | 55.5 (42.0) | .34 |

| Role emotional score, mean (SD ) | 74.0 (43.0) | 63.5 (46.7) | .36 |

| Bodily pain score, mean (SD) | 60.6 (35.7) | 46.3 (33.1) | .10 |

| Other covariates | |||

| MMSE, mean (SD) | 27.9 (3.2) | 27.7 (2.7) | .73 |

| Number of medications, n (SD) | 7.0 (3.6) | 8.6 (5.1) | .16 |

| Outcome measures | |||

| CES-D, mean (SD) | 19.6 (14.2) | 17.5 (13.2) | .54 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 143.1 (22.5) | 146.7 (20.9) | .51 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 81.4 (11.1) | 83.0 (10.7) | .58 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to antidepressant, n (%) | 16 (50.0) | 14 (43.0) | .81 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to antihypertensive, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 16 (50.0) | .31 |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; SF-36 = Medical Outcomes Study Short Form.

Note: P values represent comparisons according to Fisher’s exact test and t tests for categorical or continuous data, respectively.

Outcomes

Compared with participants in the usual care group, participants randomized to the intervention group had fewer depressive symptoms at 6 weeks (CES-D mean scores, intervention 9.9 vs usual care 19.3; P <.01). Systolic blood pressure at 6 weeks was also lower for the intervention group than for the usual care group (127.3 mm Hg vs 141.3 mm Hg, respectively; P <.01); the same was true for diastolic blood pressure (75.8 mm Hg vs 85.0 mm Hg, respectively; P <.01). The proportion of participants at 6 weeks who had 80% or greater adherence to an antidepressant medication was 71.9% in the intervention group and 31.3% in the usual care group (P <.01), and the proportion of participants who had 80% or greater adherence to an antihypertensive medication was 78.1% in the intervention group and 31.3% in the usual care group (P <.001) (Table 2 ▶).

Table 2.

Depression Symptoms, Blood Pressure, and Adherence to Antidepressant and Antihypertensive Medications of Participants in Usual Care and in the Integrated Intervention at 6 Weeks

| Variable | Usual Care (n=32) | Intervention (n=32) | PValue |

| CES-D, mean (SD), score | 19.3 (15.2) | 9.9 (10.7) | .006 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 141.3 (18.8) | 127.3 (17.7) | .003 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 85.0 (11.9) | 75.8 (10.7) | .002 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to antidepressant, n (%) | 10 (31.3) | 23 (71.9) | .001 |

| ≥ 80% adherent to antihypertensive, n (%) | 10 (31.3) | 25 (78.1) | <.001 |

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Note: P values represent statistical tests using t tests for continuous measures and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

DISCUSSION

Our preliminary study offers support for the usefulness of an integrated care intervention to improve adherence to antihypertensive and antidepressant medications, to increase blood pressure control, and to reduce depression symptoms among older primary care patients. Primary care patients randomized to an integrated care intervention, when compared with participants randomized to usual care, showed higher rates of adherence to antihypertensive and antidepressant medications, greater blood pressure control, and fewer depressive symptoms at the final study visit (6 weeks).

This study has several limitations. The first is that we used MEMS caps to measure adherence. All methods for assessing adherence have limitations: self-reports may be insensitive,32 drug levels may be influenced by factors other than treatment adherence,33 pill counts are subject erratic patient behaviors,34 verification of pharmacy records may be useful only for extended time frames,35 and MEMS caps may be expensive and opening pill bottles is assumed to be synonymous with medication ingestion.36 We chose to use MEMS caps as our primary measure of adherence because MEMS caps have a low failure rate31 and may be more sensitive than other adherence measures.37,38 In addition, prior studies have shown that MEMS caps do not significantly influence adherence.31,39 Also, any effect of MEMS caps on medication adherence would be experienced equally in both groups and, therefore, would not influence a comparative assessment by randomization assignment.

Second, we have defined an adherence threshold of 80% in our analysis. Although this threshold has been assessed in some clinical research,31 the clinical relevance of this threshold has not been tested for many medications. Third, our results were obtained from patients who received care at one primary care site that might not be representative of most primary care practices. This practice was probably similar to other primary care practices in the region, however. Fourth, our preliminary investigation was limited to 64 participants, but participants were randomized to the intervention or usual care. Fifth, participants in the intervention group may have been subject to the Hawthorne effect, in which patients are more likely to adhere to their medical regimens than they would if they were not participating in the study.40 We suspect the Hawthorne effect would be minimal in this intervention, however, as participants in the usual care group had the same number of in-person contacts as participants in the integrated care intervention. Lastly, our intervention would require additional resources in primary care settings. Even so, we have designed a simple intervention, and future implementation will explore whether ancillary health personnel could be trained to carry out the intervention.

Despite the limitations of this study, our results deserve attention because previous intervention trials in primary care have addressed depression41 and hypertension42 separately. Integrated interventions may be more feasible and effective in real-world practices, where there are competing demands for limited resources.43 In our intervention, we integrated depression treatment into care for hypertension so a single program could assist patients with depression and hypertension. Consistent with our hypothesis, patients randomized to the integrated intervention had fewer depressive symptoms, lower systolic blood pressure, lower diastolic blood pressure, and a greater proportion of participants with 80% or greater adherence to antidepressant and antihypertensive medications at 6 weeks. Of note, this intervention had a high retention rate of study participants. These findings are aligned with recent findings that older primary care patients are more likely to be engaged in integrated care than other forms of care provision,44 and integrated care models are particularly effective in improving access to and participation in mental health services among African American primary care patients.45

Many large-scale, randomized controlled trials using complex, multimodel, care management interventions have been successful in improving depression outcomes,43,46 but they have not integrated depression treatment with chronic medical conditions. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a relatively brief, pilot, randomized controlled trial with a focus on adherence for the management of depression, as well as hypertension, in primary care. Further research is needed to evaluate this intervention in a larger, more representative sample with longer periods of follow-up. Future investigations could explore the training of ancillary health personnel who are already working in primary care practices to carry out the intervention.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no financial or other relationships that would constitute a conflict of interest.

Funding support: Dr Bogner was supported by an American Heart Association Grani-in-Aid, and an NIMH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (MH67671-01), and is a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar (2004-2008).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rabins PV. Prevention of mental disorders in the elderly: current perspectives and future prospects. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(7): 727–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rost K, Pyne JM, Dickinson LM, LoSasso AT. Cost-effectiveness of enhancing primary care depression management on an ongoing basis. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):7–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogner HR, Bruce ML, Reynolds CF, III, et al. The effects of memory, attention, and executive dysfunction on outcomes of depression in a primary care intervention trial: the PROSPECT study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(9):922–929.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogner HR, Ford DE, Gallo JJ. The role of cardiovascular disease in the identification and management of depression by primary care physicians. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Ten Have T, Bruce ML. Depression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and two-year mortality among older, primary-care patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(9):748–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogner HR, Cary M, Bruce ML, et al. The role of medical comorbidity in outcome of major depression in primary care: the PROSPECT study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):861–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogner HR, Morales KH, Post EP, Bruce ML. Depression, diabetes, and death: a randomized controlled trial of a depression treatment program for older adults based in primary care (PROSPECT). Diabetes Care. 2007;30(12):3005–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogner HR, Dahlberg B, de Vries HF, Cahill EC, Barg FK. How older adults describe pathways between depression and heart disease. Fam Med. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Hajjar I, Kotchen J, Kothcen T. Hypertension: trends in prevalence, incidence and control. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:465–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawes C, Hoorn S, Law M, Elliott P, MacMoham S, Rodgers A. High blood pressure. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray C, eds. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks: Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. Vol. 1. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004:281–389.

- 12.Meyer CM, Armenian HK, Eaton WW, Ford DE. Incident hypertension associated with depression in the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment area follow-up study. J Affect Disord. 2004;83(2–3):127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Knight E, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Non-compliance with antihypertensive medications: the impact of depressive symptoms and psychosocial factors. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(7):504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balkrishnan R, Rajagopalan R, Camacho FT, Huston SA, Murray FT, Anderson RT. Predictors of medication adherence and associated health care costs in an older population with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin Ther. 2003;25(11):2958–2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(2):196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogner HR, Lin JY, Morales KH. Patterns of early adherence to the antidepressant citalopram among older primary care patients: the PROSPECT study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):103–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angst J. Clinical course of affective disorders. In: Helgason T, Daly R, eds. Depression Illness: Prediction of Course and Outcome. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1988:1–47.

- 19.Kodner D. Integrated Long Term Care Systems in the New Millenium-Fact or Fiction? American Society on Aging Summer Series on Aging; 1999.

- 20.Davies B. The reform of community and long term care of eldelry persons: an international perspective. In: Scharf T, Wenger C, eds. International Perspective on Community Care for Older People. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate; 1995:21–38.

- 21.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q. 1999;77(1):77–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundt JC, Clarke GN, Burroughs D, Brenneman DO, Griest JH. Effectiveness of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: the impact of medication compliance and patient education. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;(Suppl 20):22–33.. [PubMed]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386–2391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE. The MOS Short-form General Health Survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26(7):724–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stadnyk K, Calder J, Rockwood K. Testing the measurement properties of the Short Form-36 health survey in a frail elderly population. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(10):827–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatz M, Johansson B, Pedersen N, Berg S, Reynolds C. A cross-national self-report measure of depressive symptomatology. Int Psychogeriatr. 1993;5(2):147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Long Foley K, Reed PS, Mutran EJ, DeVellis RF. Measurement adequacy of the CES-D among a sample of older African-Americans. Psychiatry Res. 2002;109(1):61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Heart Association. Blood pressure testing and assessment. http://www.americanheart.org. Accessed Dec 14, 2007.

- 31.George CF, Peveler RC, Heiliger S, Thompson C. Compliance with tricyclic antidepressants: the value of four different methods of assessment. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):166–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roth H. Measurement of compliance. Patient Educ Couns. 1987;10:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christensen AJ, Ehlers SL. Psychological factors in end-stage renal disease: an emerging context for behavioral medicine research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(3):712–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harlow SD, Linet MS. Agreement between questionnaire data and medical records. The evidence for accuracy of recall. [see comment]. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(2):233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christensen DB, Williams B, Goldberg HI, Martin DP, Engelberg R, LoGerfo JP. Assessing compliance to antihypertensive medications using computer-based pharmacy records. Med Care. 1997;35(11):1164–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christensen AJ. Patient Adherence to Medical Treatment Regimens: Bridging the Gap Between Behavioral Science and Medicine. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004.

- 37.Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. [discussion 1073]. Clin Ther. 1999;21(6):1074–1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rudd P, Ahmed S, Zachary V, Barton C, Bonduelle D. Improved compliance measures: applications in an ambulatory hypertensive drug trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48(6):676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peveler R, George C, Kinmonth AL, Campbell M, Thompson C. Effect of antidepressant drug counselling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999;319(7210):612–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell JP, Maxey VA, Watson WA. Hawthorne effect: implications for prehospital research. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(5):590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM. Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: A randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(8):839–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers MA, Small D, Buchan DA, et al. Home monitoring service improves mean arterial pressure in patients with essential hypertension. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(11):1024–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1455–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayalon L, Arean PA, Linkins K, Lynch M, Estes CL. Integration of mental health services into primary care overcomes ethnic disparities in access to mental health services between black and white elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(10):906–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF III, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1081–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]