Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine (a) the role of neighborhood density (number of words that are phonologically similar to a target word) and frequency variables on the stuttering-like disfluencies of preschool children who stutter, and (b) whether these variables have an effect on the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced.

Method

A 500+ word speech sample was obtained from each participant (N = 15). Each stuttered word was randomly paired with the firstly produced word that closely matched it in grammatical class, familiarity, and number of syllables/phonemes. Frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency values were obtained for the stuttered and fluent words from an online database.

Results

Findings revealed that stuttered words were lower in frequency and neighborhood frequency than fluent words. Words containing part-word repetitions and sound prolongations were also lower in frequency and/or neighborhood frequency than fluent words, but these frequency variables did not have an effect on single-syllable word repetitions. Neighborhood density failed to influence the susceptibility of words to stuttering, as well as the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced.

Conclusions

In general, findings suggest that neighborhood and frequency variables not only influence the fluency with which words are produced in speech, but also have an impact on the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced.

Keywords: stuttering, language, phonological neighborhood, frequency, children

A number of linguistic factors have been shown to have an impact on the fluency with which words are produced in speech. For example, older children and adults who stutter tend to stutter more on words that are less frequently occurring in language (Danzger & Halpern, 1973; Hubbard & Prins, 1994; Palen & Peterson, 1982; Ronson, 1976; Soderberg, 1966) and longer in length (S. F. Brown, 1945; S. F. Brown & Moren, 1942; Dworzynski, Howell, & Natke, 2003; Howell & Au-Yeung, 1995; Wingate, 1967). Such phenomena have led to the suggestion that stuttering is a linguistically constrained manifestation of difficulties with linguistic formulation processes (Ratner, 1997). The notion that stuttering stems from linguistic formulation difficulties is, in fact, the sine qua non of several current models of stuttering (Au-Yeung & Howell, 1998; Perkins, Kent, & Curlee, 1991; Postma & Kolk, 1993; Wingate, 1988). For example, according to the covert repair hypothesis (CRH; Postma & Kolk, 1993), both stuttered (e.g., part-word repetitions, single-syllable word repetitions, sound prolongations, blocks, and tense pauses) and normal (e.g., multisyllable/phrase repetitions, revisions, and interjections; Yairi & Ambrose, 1992, 2005) disfluencies involve a “covert repair reaction” to some error in the speech plan. Specifically, the CRH posits that phonological processing is slower than normal in people who stutter, which increases the probability that they will select and incorporate incorrect phonemes into their phonetic plans, particularly when speech sound selections are made at a rate faster than their slower than normal phonological processing system can handle. As a result, the speech monitoring systems of people who stutter will detect more errors in the phonetic plan and, thus, create more error correction opportunities prior to articulation. When the internal monitor detects an error in the phonetic plan, it interrupts speech production, resulting in stuttered (and normal) disfluencies.

The CRH asserts that the phonological processing systems of people who stutter are quantitatively, but not qualitatively, different from those of normally fluent speakers (Kolk & Postma, 1997). Thus, whatever factors influence the occurrence of processing errors in people who stutter also should influence those of people who do not stutter—that is, there should be “a parallel between linguistic factors that determine speech errors and factors that determine stuttering” (Hartsuiker, Kolk, & Lickley, 2001, p. 65). There is some evidence in the literature to support this contention. For example, like stuttering, the speech errors of normal speakers tend to be associated with words that are longer in length (Fromkin, 1971) and lower in frequency (Dell, 1990; Dell & Reich, 1981; Stemberger, 1984). Recent speech error research, however, has revealed that production accuracy is also susceptible to a number of other linguistic influences, including phonological neighborhood density and frequency variables (e.g., Vitevitch, 1997).

As of this date, however, the effect of phonological neighborhood variables on the fluency of naturalistic speech production has not been examined. Furthermore, while the effect of word frequency on stuttering has been examined in school-age children and adults, it is not known if this variable also influences stuttering in preschool children who stutter (CWS). Nevertheless, if the CRH is correct in its prediction of congruence between linguistic factors that influence speech errors and those that influence stuttering, then these variables should have a relatively predictable effect on stuttering. Thus, the overall goal of the current study is to explore the role of neighborhood density and frequency variables on the speech fluency of young CWS. It is anticipated that this investigation might provide some insights into the speech production processes of CWS and, perhaps, help to uncover potential mechanisms that may lead to the production of stuttered disfluencies. To better appreciate further discussion of the potential role of neighborhood density and frequency variables in stuttering, it is necessary to first describe the typical effects these variables have on speech production in adults and children.

Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Effects in Speech Production

Neighborhood Density

One structural aspect of the lexicon that has received considerable attention in recent years is the role of the phonological neighborhood on the speed and accuracy with which words are recognized and produced in language. The phonological neighborhood refers to the number of words that differ in phonetic structure from another word based on a single phoneme that is either substituted, deleted, or added (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). In the mental lexicon, words are thought to be phonologically organized into dense or sparse neighborhoods according to how many phonetically similar words they have as neighbors (Charles-Luce, 2002; Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Specifically, a word that resides in a dense neighborhood, such as the word cat, has many phonetically similar words (e.g., bat, at, cab, rat, chat, that, mat, cattle, pat, gnat, etc.), whereas a word that resides in a sparse neighborhood, such as the word wolf, has few phonetically similar words (e.g., woof, wooly, and wool).

A number of studies have examined the effect of phonological neighborhoods on speech production (Goldinger & Summers, 1989; Harley & Bown, 1998; Meyer & Bock, 1992; Stemberger, 2004; Vitevitch, 1997,2002b; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). Findings from these studies indicate that words from dense neighborhoods tend to be produced more accurately and quickly than those from sparse neighborhoods (but cf. Newman & German, 2005). The most frequently referenced explanation for this phenomenon lies within the framework of interactive spreading activation models, which posit that word processing occurs as a result of bidirectional, excitatory spreading activation within a network of semantic feature, word (lexical or lemma), and phoneme (sublexical) layers (e.g., Dell, Chang, & Griffin, 1999; Dell, Schwartz, Martin, Saffran, & Gagnon, 1997; Schwartz, Dell, Martin, Gahl, & Sobel, 2006).

For example, after the target word cat is activated by its semantic features, activation spreads to its phonemes (/k/ /æ/ /t/) and back again, including all other words that happen to contain these phonemes (e.g., bat, at, cab, rat, etc.). This increase in activation of the shared phonemes will feed back to the target word (cat), thereby increasing its level of activation, along with the probability that it will be selected for production. The most activated word (cat) is eventually selected, ending the stage of lexical processing (or lemma access). The selected word is then given another boost of activation, marking the beginning of the phonological processing stage. Activation will again spread to the phoneme layer and, after a period of time, the most activated phonemes (/k/ /æ/ /t/) are selected. The selected phonemes are subsequently linked to a position in the phonological frame, thereby ending the stage of phonological processing. This model does not contain a phonological word-form (lexeme) layer, but rather word-form representations are presumed to exist in the connection between word and phoneme layers (Schwartz et al., 2006).

Based on this model, the facilitative effects of phonological density in speech production can be explained by considering that the more phonological neighbors a target word has, the more feedback activation it will receive, making the selection process easier and more efficient (Gordon, 2002). On the other hand, words from sparse neighborhoods are less likely to be accurately and rapidly retrieved from the lexicon, because they simply have fewer neighbors from which to receive feedback activation. Evidence suggests that these neighborhood density effects explicitly affect the ease with which word-form representations are accessed in speech production (Newman & German, 2005; Vitevitch, Armbrüster, & Chu, 2004).

Word Frequency and Neighborhood Frequency

In addition to neighborhood density, other lexical variables associated with frequency appear to play a role in the production of speech (Kučera & Francis, 1967; Vitevitch, 2002b; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). In particular, word frequency, or the number of times a given word occurs in a language, has been shown to influence speech production (Dell, 1990; Dell & Reich, 1981; Hubbard & Prins, 1994; Jescheniak & Levelt, 1994; Johnson, Paivio, & Clark, 1996; Martin & Saffran, 1992; Oldfield & Wingfield, 1965; Palen & Peterson, 1982; Stemberger, 1984; Vitevitch, 1997). In general, findings from these studies indicate that words that are more frequently occurring in language are produced more accurately, fluently, and rapidly than words that are less frequently occurring. It has been speculated that the locus of the frequency effect in speech production, like neighborhood density effects, is at the level of word-form retrieval (Dell, 1990; Garrett, 2001; Griffin & Bock, 1998; Harley & MacAndrew, 2001; Jescheniak & Levelt, 1994; Newman & German, 2005). Thus, the word forms of high frequency words are presumably easier to access than those of low frequency words, making it more likely that high frequency words will be produced more accurately, fluently, and quickly than low frequency ones.

Another frequency-based variable is neighborhood frequency, or the frequency of a target word's neighbors. For example, the phonological neighbors of the word dog(e.g., bog, hog, dig, log, etc.) tend to be less frequently occurring in language (mean frequency of 11.0 per million) than the phonological neighbors of the word cat (e.g., cattle, that, etc.), which are more frequently occurring in language (mean frequency of 540.2 per million). Only a few studies have examined the effect of neighborhood frequency on lexical access, the results of which have been largely inconsistent (Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Vitevitch, 1997, 2002b; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). For example, Vitevitch (1997) found that a corpus of spontaneously occurring speech errors was lower in neighborhood frequency than a control corpus of randomly selected words. On the other hand, when speech errors were elicited in a controlled task, no influence of neighborhood frequency was observed (Vitevitch, 2002b).

The effects of neighborhood frequency are presumed to be due to spreading activation in the connections between words and phonemes (Vitevitch, 1997; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). As will be recalled, one component of the interactive speech production model (e.g., Dell et al., 1997) is that the activation of a target word spreads to its phonological neighbors and then back again, thereby increasing the target word's level of activation. However, if the phonological neighbors have a higher frequency of occurrence (i.e., they are initially more highly activated), then the net effect will be to further increase the amount of target word activation. Therefore, words with high neighborhood frequencies will be more likely to be produced accurately and quickly, because they receive greater amounts of activation through their shared phonemes (Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). On the other hand, if the phonological neighbors of the target word are lower in frequency (i.e., they are initially less highly activated), then the target word will receive less feedback activation from their shared phonemes. As a result, words with low neighborhood frequencies will be less likely to be completely retrieved, thereby increasing the probability than an error will be produced.

Children's Lexical Representations

As revealed in the preceding review, most research concerning lexical representation organization has been based on the adult lexicon. Furthermore, of the few studies that have examined children's lexical representations, most have focused on word recognition processes, rather than speech production (e.g., Munson, Swenson, & Manthei, 2005). Nevertheless, findings from most speech production studies indicate that the lexical factors of word frequency, neighborhood density, and/or neighborhood frequency have the same general pattern in children as in adults (Gierut, 2001; Gierut, Morrisette, & Champion, 1999; German & Newman, 2004; Morrisette & Gierut, 2002; Newman & German, 2002; Stemberger, 1984; Storkel & Morrisette, 2002).

Lexical Effects on Error Patterns

From this review, it is clear that lexical variables have an impact on the productions of adults and children, but a relevant question is whether such variables can also be used to characterize and predict the types of production errors that may result. Several lexical variables have, in fact, been shown to have an impact on the production of different error patterns of adults with normal speech production. For example, Harley and MacAndrew (2001) reported that words with spontaneously occurring phonological substitution errors (target and error words are related in sound) were lower in frequency and longer in length than words with and without semantic substitution errors (target and error words are related in meaning). On a general level, the authors interpreted these findings to suggest that different error types originate in the disruption of different levels of processing. On a more concrete level, however, the authors proposed that phonological substitution errors result from difficulty with aspects of word form retrieval, rather than semantic aspects.

Research indicates that, as with adults, children's error patterns may be influenced by various lexical factors. For example, German and Newman (2004) examined the lexical characteristics of three error patterns (word form, phoneme, and semantic errors) in school-age children with word-finding difficulties. The authors defined word-form errors as substitutions that involved a response (a) to a known target word that was correct, but delayed, (b) that contained no attributes of the target word (e.g., no response or “I don't know”), or (c) that consisted of a description of the target word (e.g., you eat it for peanut). Phoneme errors were defined as substitutions that consisted of phonological approximations of the target word (e.g., pea for peanut), whereas semantic errors were substitutions of semantically related words for target words (e.g., almond for peanut). Their findings revealed that words containing (a) word-form errors were more likely to occur on words residing in sparse neighborhoods, (b) phoneme errors were more likely to occur on words that were low in frequency and neighborhood frequency, and (c) semantic errors were not at all influenced by neighborhood variables.

According to German and Newman (2004), because word-form errors occurred more often on words in sparse neighborhoods, the locus of difficulty for these words was in accessing the word's lexical space. Specifically, because these words have fewer neighbors, the “access paths” in their region of the lexicon were presumably not as strong or well-formed, which increased the probability that a word-form error would be produced. On the other hand, they speculated that the point of difficulty for phoneme errors was in accessing the word's phonological segments or segment combinations. More specifically, they argued that low frequency words and words with low frequency neighbors contain less commonly occurring phonemes and phoneme combinations and, as a result, they are accessed relatively infrequently, resulting in less developed access paths and greater susceptibility to phonologic errors. Finally, because semantic errors could not be predicted by neighborhood variables, the authors posited that these errors “occur for reasons other than lexical factors of word form” (p. 630). In sum, these findings suggest that different types of word errors in children's speech may be related to different levels of disruption in lexical processing.

Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Effects in Stuttering

As previously indicated, there has been no attempt to systematically examine the effect of neighborhood density and neighborhood frequency on the production of spontaneously occurring stuttered disfluencies. Furthermore, while the effect of word frequency on stuttering has been examined in school-age children (e.g., Palen & Peterson, 1982) and adults (e.g., Hubbard & Prins, 1994), its effect on stuttering in preschool CWS has not been previously examined. In a recent study, however, Arnold, Conture, and Ohde (2005) examined the influence of neighborhood density on the speed and accuracy of picture naming in preschool CWS and their normally fluent peers. Eighteen children (9 participants per group) were shown pictures that were either high or low in neighborhood density and then asked to name each picture “as soon as [they] see it.” Findings revealed that both groups of children were less accurate and slower to name pictures of high density words than low density words. There was no significant difference, however, in neighborhood density effects between the two groups of children. The authors indicated that their findings were consistent with those of Newman and German (2002), who reported that school-age children had more difficulty naming words with high neighborhood density than those with low neighborhood density. However, their findings contradict those of most other studies in which low density words are reportedly more difficult for children and adults to accurately and rapidly retrieve from the lexicon than high density words (e.g., German & Newman, 2004; Stemberger, 2004; Vitevitch, 1997, 2002b).

Findings from Arnold et al. (2005) indicate that neighborhood density has an influence on the accuracy and speed with which words are produced by preschool children. However, the fact that no differences were found in neighborhood density effects between CWS and their normally fluent peers would seem to argue against the notion, made popular by the CRH and supported by several recent empirical investigations (e.g., Byrd, Conture, & Ohde, 2006; Hakim & Ratner, 2004) that developmental stuttering may be related to phonological processing difficulties. Perhaps one reason why CWS in the Arnold et al. study could not be differentiated from their peers in their response to neighborhood density effects is related to what the study was designed to measure—the speed and accuracy of perceptually fluent, one-word responses. Thus, one might argue that their findings fail to provide support for a generalized phonological processing delay or deficit in CWS, as one might expect such delays/deficits to be present during both fluent and nonfluent speech. These findings, however, do not preclude the possibility that CWS experience transient difficulties in phonological processing that are directly related to the moment of stuttering. It also does not exclude the possibility of transitory activation or planning difficulties in more than one linguistic formulation process—that is, “The problem for individual CWS could be different at different times, depending on the nature of the particular conversational interaction” (Anderson & Conture, 2004, p. 566).

Following from such speculation is the notion that different types of stuttered disfluency may be related to disruptions at different processing levels (Conture, Zackheim, Anderson, & Pellowski, 2004; Wingate, 1988). Although few attempts have been made to empirically assess the validity of this claim, a theoretical account of the origins of different types of stuttering has been proposed by the authors of the CRH (Kolk & Postma, 1997; Postma & Kolk, 1993). In general, the CRH posits that the form of fluency breakdown depends on the size and type of internal error generated, as well as the type of covert repair strategy used. Specifically, single-syllable word repetitions are presumed to result from an internal lexical (lemma) error, which is covertly corrected upon detection by restarting the previously produced word. An internal phoneme (sublexical) error, on the other hand, is repaired by restarting from the beginning of the interrupted syllable, after the first sound of the syllable has already been produced. This results in either a part-word repetition or sound prolongation, depending on how much of the current syllable has already been produced prior to restarting and whether the sound is a continuable phoneme.

In summary, findings from studies of children and adults indicate that word frequency and neighborhood variables influence the susceptibility of words to accurate production. Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that these variables might also influence the fluency of speech produced by preschool CWS. This proposition is based, in part, on the assumptions of the CRH, which posit that stuttering should be constrained by the same linguistic factors as speech errors. If the CRH is correct, then CWS should stutter on words that are lower in frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency relative to a control corpus of their fluent words. Findings from speech production studies have further revealed that error patterns are differentially influenced by various lexical factors, suggesting that different error types originate in the disruption of different levels of speech-language production. If the same is true of stuttered disfluency types, as suggested above, then they should be susceptible to different lexical influences. Specifically, if words containing part-word repetitions and sound prolongations result from difficulties at the phonological processing level (like phonological errors), then they should be vulnerable to the effects of neighborhood density and frequency variables. Thus, it is predicted that children will produce part-word repetitions and sound prolongations on words that are lower in frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency relative to a control corpus of fluent words. On the other hand, if words containing single-syllable word repetitions result from difficulties at some other level of processing, such as lexical encoding (like semantic errors), then they should not be susceptible to the effects of neighborhood density and frequency variables. That is, there should be no significant difference in word frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency between children's productions of words containing single-syllable word repetitions and those that are fluently produced.

Method

Participants

Fifteen CWS (10 males, 5 females) between the ages of 3;0 (years;months) and 5;2 participated in this study (mean age = 48.5 months, SD = 6.3; see Table 1). All participants were native speakers of American English with no apparent or reported history of neurological, speech-language (other than stuttering), hearing, or intellectual problems, per parent report and examiner observation or testing. Participants were identified for participation in this study by their parents, who were made aware of this study through advertisements in several local news periodicals in the south-central Indiana area (Bloomington and surrounding areas).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics for standardized speech-language measures and stuttering measures.

| Participant | Age (months) | Gender | PPVT-III | EVT | TELD-3 | GFTA-2 | TSO | %SLD | SSI-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | M | 101 | 97 | 90 | 90 | 24 | 3.2 | 20 |

| 2 | 51 | M | 104 | 115 | 123 | 100 | 15 | 3.5 | 23 |

| 3 | 58 | F | 119 | 120 | 129 | 92 | 20 | 3.9 | 20 |

| 4 | 51 | F | 97 | 107 | 109 | 111 | 27 | 7.4 | 29 |

| 5 | 51 | M | 123 | 107 | 124 | 102 | 9 | 10.9 | 23 |

| 6 | 50 | M | 94 | 91 | 91 | 109 | 24 | 3.8 | 28 |

| 7 | 42 | F | 116 | 119 | 119 | 94 | 7 | 4.9 | 20 |

| 8 | 43 | M | 126 | 111 | 134 | 103 | 6 | 15.5 | 31 |

| 9 | 43 | F | 93 | 113 | 101 | 124 | 20 | 5.9 | 26 |

| 10 | 56 | M | 109 | 102 | 96 | 93 | 12 | 4.8 | 24 |

| 11 | 51 | M | 108 | 103 | 99 | 97 | 9 | 3.0 | 18 |

| 12 | 57 | M | 116 | 133 | 113 | 118 | 33 | 3.1 | 15 |

| 13 | 41 | M | 96 | 112 | 122 | 99 | 2 | 4.8 | 20 |

| 14 | 49 | F | 108 | 117 | 117 | 100 | 9 | 3.0 | 12 |

| 15 | 36 | M | 93 | 98 | 102 | 117 | 3 | 7.4 | 16 |

| M | 48.5 | 106.9 | 109.7 | 111.3 | 103.3 | 14.7 | 5.7 | 21.7 | |

| SD | 6.3 | n/a | 11.2 | 10.7 | 14.1 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 5.4 |

Note. PPVT-III = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition (standard score); EVT = Expressive Vocabulary Test (standard score); TELD-3 = Test of Early Language Development-3 (standard score); GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation-2 (standard score); TSO = parent-reported timex since initial onset of stuttering (months); %SLD = mean frequency of stuttering-like disfluencies (percent) per 100 words; SSI-3 = Stuttering Severity Instrument-3 (total score).

Inclusion and Classification Criteria

For inclusion and classification purposes, children responded to four standardized speech and language measures, completed a hearing screening, and participated in a parent–child conversational interaction. Participants were assessed on one occasion for 1 to 1½ hr in the Speech Disfluency Laboratory at Indiana University.

Speech-Language Measures and Hearing Screening

To participate in this study, children were required to score within normal limits (within 1 SD below the mean) on four standardized speech and language tests, including the (a) Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Third Edition (PPVT-III; Dunn & Dunn, 1997), (b) Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT; Williams, 1997), (c) Test of Early Language Development-3 (TELD-3; Hresko, Reid, & Hamill, 1999), and (d) the Sounds-in-Words subtest of the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation-2 (GFTA-2; Goldman & Fristoe, 2000). Age-based standard scores were obtained for the PPVT-III, EVT, TELD-3, and the GFTA-2 subtest using the scoring methods outlined in the test manuals (see Table 1). Each child's hearing also was screened using bilateral pure-tone testing at 20 dB SPL for 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz and impedance audiometry from +400 to −400 daPa (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 1990). All children passed the hearing screening.

Stuttering Measures

To be classified as a CWS, each child had to (a) exhibit a mean frequency of three or more (percent) stuttering-like disfluencies (part-word repetitions, single-syllable word repetitions, sound prolongations, blocks, or tense pauses) per 100 words of conversational speech (Yairi & Ambrose, 1992, 1999, 2005; cf. Pellowski & Conture, 2002),1 (b) receive a total overall score of 11 or higher on the Stuttering Severity Instrument-3 (SSI-3; Riley, 1994), and (c) have parent(s) or caregiver(s) in the environment who were concerned about his or her stuttering. Average parent-reported time since initial onset of stuttering (TSO) was determined using the “bracketing” procedure described by Yairi and Ambrose (1992; cf. Anderson, Pellowski, Conture, & Kelly, 2003). Only one child received treatment for stuttering in the 9 months prior to participating in this study. The mean percent stuttering-like disfluency, SSI-3, and TSO scores for each participant are revealed in Table 1.

Parent–Child Conversational Interaction

To determine whether participants met the criteria for classification as CWS, as well as for subsequent analyses of the main dependent variables (see below), conversational speech samples were obtained for each child during a parent–child interaction. The child and his or her parent(s) verbally interacted with one another while seated at a small table with age-appropriate toys. A 500+ word speech sample was elicited from each participant during the parent–child interaction, with each session lasting approximately 20 to 30 min (mean sample = 849.1 words, SD = 329.3). Each parent–child interaction was videotaped usingtwo color video cameras (EV1-D30), a Unipoint AT853 Rx Miniature Condenser Microphone, and a Panasonic DVD/HD video recorder (Model N. DMR-HS2).

Procedures

Transcript Analyses

Stuttering-like and other disfluencies

All videotaped conversational speech samples were transcribed into the computer using the using the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT) software program (Miller & Chapman, 1998) and its basic transcription conventions. For participant inclusion purposes, each transcript was analyzed for the mean frequency of stuttering-like disfluencies per 100 words and stuttering severity, as measured by the SSI-3 (see above). For all subsequent descriptive and inferential statistical analyses, only words containing part-word repetitions (e.g., “b* b* but,” “ba* ba* baby”), single-syllable word repetitions (e.g., “but-but-but,” “you-you-you”), and sound prolongations (e.g., “wwwwhat,” “mmmmommy”) were included in the data corpus. There were a few instances of tense pauses and blocks in the participants' speech samples. However, tense pauses were excluded from the data corpus because these audible, tense vocalizations occur between words and are often difficult to reliably distinguish in the speech of young children (Yairi & Ambrose, 1992, 1999, 2005). In addition, blocks were excluded from the data corpus, because they occurred with insufficient frequency—only 2 of the 15 participants (13%) exhibited these behaviors, with a mean frequency of 0.83% per 100 words.

All other (“normal”) disfluencies (Yairi & Ambrose, 1992, 1999, 2005), including multisyllable/phrase repetitions, revisions, and interjections, were not included in the data corpus, because the focus of the present study was on the lexical characteristics of words that are most apt to be perceived as stuttering (i.e., stuttering-like disfluencies). Phrase repetitions and revisions also were excluded because they involve more than one lexical item (e.g., “I ride on a … I ride on a horse”) and the dependent variables analyzed in this study represent structural and organizational features of the lexicon. Interjections also were subject to exclusion because their linguistic status (i.e., whether or not they are English words) has yet to be determined (Clark & Fox Tree, 2002). This analysis procedure resulted in a total of 652 words containing part-word repetitions, single-syllable word repetitions, and/or sound prolongations across participants.

Word pair matching

For each participant, words containing stuttering-like disfluencies were randomly paired with the first subsequently produced fluent word that matched it on a predetermined set of dimensions. Hereafter, these are referred to as the stuttered word and control word, respectively. Specifically, the stuttered and control words were matched exactly by grammatical class (content and function words), because previous studies have demonstrated that content and function words differ in their lexical characteristics and susceptibility to errors (Gordon, 2002; Vitevitch, 1997). There were several instances in which the stuttered or control word could function as either a content or function word, depending on the context of the utterance. For example, in the sentence, “I have many books,” the word have is a main verb and it, thus, functions as a content word. On the other hand, in the sentence, “I have seen the Grand Canyon,” the auxillary verb have operates as a function word. If a stuttered word had a grammatical class that varied depending on the context of the utterance, then it was removed from the data corpus. If a control word had a context-variable grammatical class, however, then the next fluently produced word that matched it was selected. Of the 652 stuttered words initially obtained from the transcripts, 8 (1.2%) words were omitted because of the variability of their grammatical class, resulting in a total of 644 useable word pairs (stuttered words and their matched controls) across participants. Of these 644 word pairs, 184 (28.6%) were content words and 460 (71.4%) were function words.

Each word pair also was matched exactly for number of syllables to control for the possible confound of word length and the neighborhood density effect, because shorter words tend to be higher in frequency and have more dense neighborhoods than longer words (Bard & Shillcock, 1993; Coady & Aslin, 2003; Pisoni, Nusbaum, Luce, & Slowiaczek, 1985). Of the 644 word pairs, 610 (94.7%) were single-syllable words, 31 (4.8%) were two-syllable words, and 3 (0.47%) were three-syllable words. To further control for the possible effect of word length, each word pair also was matched, as closely as possible, for number of phonemes (see the Results section for details). The stuttered and control words were further equated, as closely as possible, for word familiarity to ensure that the two samples of words were of similar familiarity. Word familiarity refers to the extent to which a word is considered to be well-known by adult listeners, and while it tends to be correlated with word frequency, it is not always the case (e.g., the frequency of occurrence for the word acorn is low, but adults typically rate it as highly familiar; German & Newman, 2004; Nusbaum, Pisoni, & Davis, 1984). Familiarity values were obtained from an online database (see below; Nusbaum et al., 1984).

Lexical Analysis

The stuttered and control words (N = 1,288) were submitted to an online database (the Hoosier Mental Lexicon) to obtain values for familiarity, frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency. This database contains the transcriptions of approximately 20,000 words from Webster's Pocket Dictionary (see Luce & Pisoni, 1998; Luce, Pisoni, & Goldinger, 1990; Nusbaum et al., 1984; available from http://128.252.27.56/neighborhood/Home.asp). Frequency and neighborhood frequency values in this database are based on the written American English counts of Kučera and Francis (1967), while all other lexical values are from Luce and Pisoni (1998). Familiarity ratings in this database were obtained by having adults rate the subjective familiarity of each word on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (don't know the word) to 7 (know the word and know its meaning) (see Nusbaum et al., 1984). Neighborhood density values in this database were computed by counting the number of words in the dictionary that differed from a given word by a one-phoneme substitution, addition, or deletion (see Luce & Pisoni, 1998). Although this database is based on the adult lexicon, its consistent use in the literature makes it particularly suitable for making direct comparisons between findings from the present investigation and those of others (e.g., Vitevitch, 1997). Perhaps more importantly, the values reported in this database have not only been shown to be highly and positively correlated with child values (Jusczyk, Luce, & Charles-Luce, 1994; Walley & Metsala, 1992), but they also have resulted in identical conclusions when applied to an actual set of child data and then differentially compared to the child databases (Dale, 2001; Gierut & Storkel, 2002).

Most of the stuttered and control words were submitted to the online database in orthographic form, after removing their inflectional morphemes (number and tense marking). However, because the database of 20,000 words is relatively small compared to the lexicon as a whole, not all words were found in the database (Luce & Pisoni, 1998). The data corpus contained 31 words whose neighborhood values were not available in the online database. The neighborhood values for these 31 words were obtained from a phonetic database maintained by Michael Vitevitch at the University of Kansas, while word frequency values were obtained from the MRC Psycholinguistic Database (Wilson, 1988; available from http://www.psy.uwa.edu.au/mrcdatabase/uwa_mrc.htm), based on the counts of Kučera and Francis (1967).

Data Analysis

Nonparametric statistics were used to analyze the data in this study, because samples for all three variables were drawn from highly skewed distributions, thereby violating the normality assumption for parametric tests. Furthermore, attempts to power transform the data, so that parametric statistics could be applied (as has been done in other, similar investigations; e.g., German & Newman, 2004; Vitevitch, 1997), failed to correct the underlying distribution, leaving nonparametric statistics, which do not rely on the assumption of normally distributed data, as the most reliable means of statistical testing (Fields, 2005; Higgins, 2004). Pearson's correlation coefficient r is reported as an effect size measure for each statistical comparison, with an r of .50 representing a large effect, .30 a medium effect, and .10 a small effect (Cohen, 1988,1992). Bonferroni adjustments were also applied, where appropriate, to alpha to maintain the familywise potential for a Type I error at .05.

Measurement Reliability

Stuttering-like disfluency measures

Interjudge reliability was assessed for judgments of the three main types of stuttering-like disfluency (part-word repetitions, single-syllable word repetitions, sound prolongations) examined in this study, based on the conversational speech samples of four randomly selected participants. The conversational speech samples of these four participants included a total of 2,989 words and represented approximately 24% of the total data corpus (there was a total of 12,737 words for all 15 participants). The author and a trained graduate student independently observed the same four recordings and then identified each stuttering-like disfluency type. The following point-by-point measurement agreement index was used to calculate the reliability percentage: (number of agreements/number of agreements + disagreements) × 100 (Sander, 1961). Interjudge measurement reliability was 86% for part-word repetitions, 90% for single-syllable word repetitions, and 81% for sound prolongations.

SALT transcripts

Interjudge reliability was also assessed for the accuracy of the SALT transcripts, based on the conversational speech samples of the same four randomly selected participants used for stuttering-like disfluency reliability. Two undergraduate honor students, trained by the author, independently retranscribed each speech sample using SALT. A point-to-point (i.e., word-to-word) comparison was then conducted for each SALT transcript, whereby it was noted whether the two samples or raters agreed or disagreed with one another for each transcribed word. Using Sander's (1961) agreement reliability formula, interjudge agreement reliability for words in the SALT transcripts was 90%.

Results

Effect of Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Variables on Stuttering

The primary objective of this analysis was to assess whether phonological neighborhood density and frequency variables influence the susceptibility of words to stuttering. This was accomplished by comparing the word frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency values of words containing stuttered disfluencies to a corpus of normally fluent (control) words. Mean neighborhood density and frequency values for the stuttered and control words were calculated for each child, as the total number of useable word pairs varied widely across participants (M = 42.9 word pairs, SD = 25.4, range: 16–101).

As will be recalled, stuttered and control words were matched exactly by grammatical class and number of syllables and, as closely as possible, by number of phonemes and word familiarity. Thus, descriptive and nonpara-metric statistics were first used to assess whether the two samples of words were, in fact, comparable in number of phonemes and word familiarity. The stuttered words had a group mean (i.e., mean of the individual participants' means) of 2.64 (SD = 0.18) phonemes and the control words had a group mean of 2.67 (SD = 0.19) phonemes. A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test revealed no significant difference between the stuttered and control words in phoneme number (z = −.69, p = .48, r = −.13). Although word pairs were not matched exactly for familiarity, the stuttered and control words both had group mean familiarity values of 6.91 (SD = .05). A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test revealed no significant difference between the stuttered and control words in familiarity (z = −.71, p = .48, r = −.13). Because word pairs were not only identical in grammatical class and number of syllables, but also comparable in number of phonemes and word familiarity, any potential differences found between stuttered and control words in word frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency were not likely to be biased by these other lexical variables.

Word Frequency

A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (Bonferroni corrected) indicated that children's stuttered words (M = 6363.65, SD = 2715.49) were significantly lower in word frequency than their control words (M = 11992.17, SD = 5271.94), z = −2.84, p .01, r = −.52. Inspection of the individual data revealed that 13 of the 15 CWS (87%) exhibited lower word frequency values for the stuttered words compared to the control words, whereas only 2 CWS (13%) exhibited the opposite effect (i.e., word frequency values were higher for the stuttered words). Thus, word frequency appears to influence the susceptibility of words to stuttering, such that children tend to stutter on words that are of lesser frequency compared to those they produced fluently.

Neighborhood Density

A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test revealed no significant difference between children's stuttered (M = 18.27, SD = 2.15) and control (M = 17.46, SD = 2.28) words in neighborhood density (z = −1.76, p = .07, r = −.32), although statistical power was low (power = .14). On an individual participant basis, 11 of the 15 CWS (73%) tended to stutter more on words with higher density values than the control words (mean individual difference = .80, SD = 1.95), 3 CWS (25%) stuttered more on words with lower density values, and 1 CWS (6.7%) had nearly identical values for the two groups of words. Thus, even though there was a tendency for the stuttered words of some children to be higher in neighborhood density than those that were fluently produced, this difference was quite small and neighborhood density did not have an appreciable effect on speech fluency for CWS as a group.

Neighborhood Frequency

A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (Bonferroni corrected) indicated that children's stuttered words (M = 824.96, SD = 298.71) were significantly lower in neighborhood frequency than their control words (M = 1386.06, SD = 795.29), z = −2.50, p ≤.01, r = −.46. Inspection of the individual participant data revealed that 13 of the 15 CWS (87%) exhibited lower neighborhood frequency values for stuttered words compared to control words, while only 2 CWS (13%) exhibited higher neighborhood frequency values for stuttered words. These findings indicate that children, as a group, stuttered on words that had phonological neighbors that were lower in frequency relative to those they produced fluently.

Effect of Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Variables on Stuttering Types

The goal of this analysis was to assess whether phonological neighborhood density and frequency variables have an effect on the type of stuttered disfluency produced. This was accomplished by comparing the word frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency values of stuttered and control words for each type of stuttered disfluency. For these analyses, words containing more than one type of stuttering-like disfluency were removed from the data corpus (e.g., “Wh* wh* wh* where where does that horsie go?”). This resulted in the exclusion of 26 words from the initial sample of 644 stuttered words, leaving a total of 618 stuttered words available for analysis.

Of the 618 available stuttered words, 291 contained part-word repetitions, 267 single-syllable word repetitions, and 60 sound prolongations. There were fewer available words containing sound prolongations, as 5 children failed to produce any sound prolongations and 4 children had only one or two sound prolongations. For each stuttering-like disfluency type, stuttered words were paired with the same control words used in the previous analysis, matched exactly by grammatical class and number of syllables and, as closely as possible, by number of phonemes and word familiarity. Friedman's analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed no significant difference between stuttered and control words in phoneme number, χ2(1) = .03, p = .87, and word familiarity, χ2(1) = .50, p = .47, across stuttering-like disfluency types. Mean neighborhood density and frequency values were calculated for each participant for words containing part-word and single-syllable word repetitions, and their corresponding control words. However, because the number of available words containing sound prolongations varied considerably across participants, mean neighborhood density and frequency values were only calculated for the 6 children who produced at least three or more of these stuttering-like disfluency types, along with their corresponding control words. As with the previous analysis, nonparametric matched samples tests (Friedman's ANOVA and, where appropriate, Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests) were chosen as the method of statistical analysis, as data were non-normally distributed and not correctable via power transformations.

Word Frequency

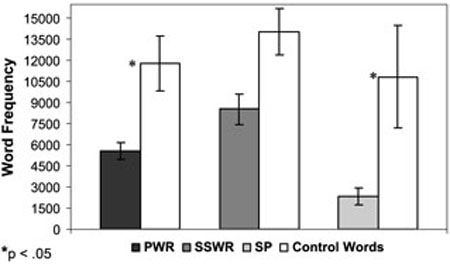

Friedman's ANOVA revealed a significant difference between children's stuttered and control words in frequency across stuttering-like disfluency types, χ2(1) = 14.24, p < .001 (see Figure 1). Follow-up Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests (Bonferroni-corrected) indicated that children's words containing part-word repetitions (M = 5563.04, SD = 2288.73) were significantly lower in frequency than their corresponding control words (M = 11785.31, SD = 7293.15), z = −2.48, p ≤ .01, r = −.45. Similarly, children's words containing sound prolongations (M = 2347.51, SD = 1472.14) were significantly lower in frequency than their control words (M= 10848.38, SD = 8861.50), z = −2.20, p < .01, r = −.64. Although children produced single-syllable word repetitions (M = 8538.32, SD = 4112.44) on words that were lower in frequency than their control words (M = 14062.89, SD = 6226.99), this difference was no longer significant following Bonferroni correction (z = −2.35, p = .03, r = −.43, power = .20). These findings generally indicate that children produced part-word repetitions and sound prolongations on words that are less frequently occurring in language than those produced without stuttering. Furthermore, children produced single-syllable word repetitions on words of relatively comparable frequency to those produced fluently. Interpretation of this latter finding should be viewed cautiously, however, considering that without the Bonferroni correction, the difference in frequency between words containing single-syllable word repetitions and those that were fluently produced would have achieved statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Mean (and standard error of the mean) frequency values (y-axis expressed per million) for words containing part-word repetitions (PWR) and control words (n = 15), single-syllable word repetitions (SSWR) and control words (n = 15), and sound prolongations (SP) and control words (n = 6) for children who stutter between the ages of 3;0 (years;months) and 5;2.

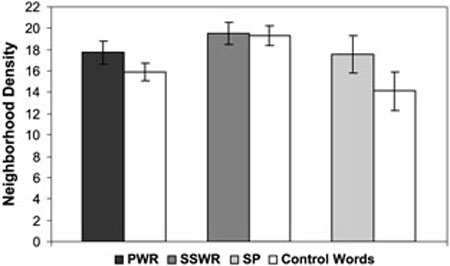

Neighborhood Density

Friedman's ANOVA revealed no significant difference between children's stuttered and control words in neighborhood density across stuttering-like disfluency types, χ2(1) = 1.88, p = .17, r = −.45, power = .22 (see Figure 2). Thus, these findings indicate that neighborhood density does not have an appreciable effect on the type of stuttered disfluency children produced.

Figure 2.

Mean (and standard error of the mean) neighborhood density values (y-axis refers to the number of phonologically similar neighbors) for words containing part-word repetitions (PWR) and control words (n = 15), single-syllable word repetitions (SSWR) and control words (n = 15), and sound prolongations (SP) and control words (n = 6) for children who stutter between the ages of 3;0 and 5;2.

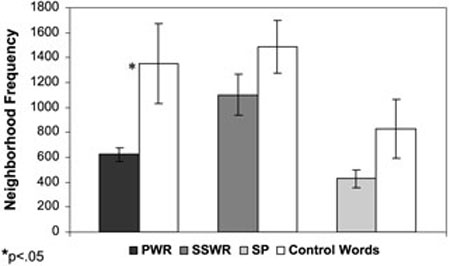

Neighborhood Frequency

Friedman's ANOVA revealed a significant difference between children's stuttered and control words in neighborhood frequency across stuttering-like disfluency types, χ2(1) = 16.94,p < .001 (see Figure 3). Follow-up Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests, with Bonferroni corrections applied, indicated that children's words containing part-word repetitions (M = 623.12, SD = 213.16) were significantly lower in neighborhood frequency than their corresponding control words (M = 1349.90, SD = 1197.88), z = −3.29, p ≤ .001, r = −.60. Children produced sound prolongations on words (M = 428.96, SD = 172.75) that were also lower in neighborhood frequency than their control words (M = 830.00, SD = 575.16). This difference was not, however, statistically significant (z = −1.57,p = .12, r = −.45), although statistical power was determined to be low for this analysis (power = .11). There was no significant difference in neighborhood frequency between children's words that contained single-syllable word repetitions (M = 1101.54, SD = 627.39) and their matching control words (M = 1484.57, SD = 787.82), z = −1.48, p = .14, r = −.27, but power was again low (power = .11). These findings indicate that children produced part-word repetitions on words whose phonological neighbors were lower in frequency of occurrence than those they produced fluently. Neighborhood frequency, however, did not have a significant effect on children's productions of single-syllable word repetitions and sound prolongations.

Figure 3.

Mean (and standard error of the mean) neighborhood frequency values (y-axis expressed per million) for words containing part-word repetitions (PWR) and control words (n = 15), singlesyllable word repetitions (SSWR) and control words (n = 15), and sound prolongations (SP) and control words (n = 6) for children who stutter between the ages of 3;0 and 5;2.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of word frequency and phonological neighborhood variables on the susceptibility of words to stuttering in preschool CWS, as well as to assess whether these variables influence the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced. As summarized in Table 2, results revealed that children stuttered on words that were lower in frequency and neighborhood frequency relative to a control sample of their fluently produced words. Furthermore, children's words containing part-word repetitions and sound prolongations were lower in frequency and/or neighborhood frequency than those they produced fluently, but these frequency variables did not influence their production of single-syllable word repetitions to the same degree. Neighborhood density did not have a significant impact on the overall fluency with which words were produced nor did it have an influence on the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced. What follows is a further discussion of these results.

Table 2. Summary of findings.

| Word frequency |

Neighborhood density |

Neighborhood frequency |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stuttered vs. control words | ||||

| Stuttered words | Lower* | Similar | Lower* | |

| Control words | Higher | Similar | Higher | |

| Stuttered vs. control words by type | ||||

| Part-word repetitions | Lower* | Higher | Lower* | |

| Control words | Higher | Lower | Higher | |

| Single-syllable word repetitions | Lower | Similar | Lower | |

| Control words | Higher | Similar | Higher | |

| Sound prolongations | Lower* | Higher | Lower | |

| Control words | Higher | Lower | Higher | |

difference is significant at p ≤.05.

Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Effects on Stuttering

The Role of Word Frequency

This study represents the first attempt to examine the effect of word frequency on the stuttering-like dis-fluencies of preschool CWS. Results indicate that the previously reported effect of word frequency on speech fluency for older children and adults who stutter (Danzger & Halpern, 1973; Hubbard & Prins, 1994; Palen & Peterson, 1982; Ronson, 1976; Soderberg, 1966) also holds true for preschool CWS—that is, young children, like their older counterparts, are more apt to stutter on low frequency words than high frequency words. Findings are also consistent with studies that have reported that speech errors, malaproprisms, and tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) states in children and adults tend to occur more often on words that are lower in frequency relative to words that are higher in frequency (e.g., R. Brown & McNeill, 1966; Dell & Reich, 1981; Newman & German, 2002; Stemberger & MacWhinney, 1986; Vitevitch, 1997). In essence, these results complement the existing literature on stuttering by expanding the influence of lexical frequency to include preschool CWS.

Previous accounts of the word frequency effect in stuttering have suggested that words that are lower in frequency are more vulnerable to fluency disruptions because they are either less familiar to speakers (Wingate, 1988) or more prominent in that they tend to introduce new and/or important information (S. F. Brown, 1938). However, another possible explanation for this effect, which has not been considered in the stuttering literature, can be derived from models of spoken word recognition, in which the effects of word frequency are thought to be directly related to processing demands (Morrisette & Gierut, 2002). Specifically, the processing load for high frequency words is thought to be reduced because “the path to retrieving these forms is well-established, as they occur so often in the input” (Morrisette & Gierut, 2002, p. 154). Therefore, because high frequency words occur frequently in language, their access paths are more strongly represented in the lexicon, which enables them to be processed with much less attention and effort. As a result, these words will be more resistant to fluency disruptions and other speech errors. On the other hand, low frequency words would be expected to have less tenable pathways, because they are not commonly used in language and, thus, require more time and energy to process. Consequently, these words will be more vulnerable to stuttering-like disfluencies and speech errors, because more effort must be expended for them to be accurately and fluently retrieved from the lexicon.

In addition to influencing the ease of processing, word frequency also may have an impact on the specificity of phonological representations. In this way, because the processing paths of high frequency words are more frequently traveled, the sublexical representation of the words themselves would become more robust (i.e., they would have more phonological detail; see Garlock, Walley, & Metsala, 2001; Metsala & Walley, 1998). If the segmental composition of high frequency words is more firmly established in the lexicon, then the exact segments that are associated with these words will be known, and in this less uncertain environment, words are more likely to be accurately and fluently produced. On the other hand, because the pathways of low frequency words are less frequently traveled, their phonological representations may have less specificity, making them more vulnerable to disruption. In this case, the lack of a fully specified segmental composition may result in the child getting “hung up” on which segments are needed, making it more likely that the word will be stuttered on or inaccurately produced.

The Role of Neighborhood Density

It was initially hypothesized that the stuttered disfluencies of CWS would be lower in neighborhood density than a control corpus of their fluently produced words. This hypothesis was based, in part, on the fact that words with sparse neighborhoods tend to be more amenable to speech errors, word-finding errors, and TOT states than words with dense neighborhoods in both children and adults (e.g., Charles-Luce, 2002; German & Newman, 2004; Gordon, 2002; Harley & Bown, 1998; Vitevitch, 1997, 2002b; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). Contrary to expectations, however, results revealed that phonological density did not have an effect on the fluency with which words are produced. These findings also are contrary to those of Arnold et al. (2005), who found that neighborhood density had an influence on the accuracy and speed of word production by preschool CWS and their normally fluent peers (although children tended to have more difficulty with words from dense neighborhoods than sparse neighborhoods; cf. Newman & German, 2002).

The present findings should be viewed cautiously given the marginal significance and low power in the analysis. However, if these findings are taken at face value, then the question is, why did neighborhood density fail to have the hypothesized effect on the production of stuttering-like disfluencies? One possible explanation for the failure of neighborhood density to influence the production of stuttering-like disfluencies can be found in Storkel (2004). Specifically, Storkel reported that neighborhood density effects on lexical acquisition in naturalistic settings were apparent for low frequency words but not high frequency words. She suggested that this apparent relationship between word frequency and neighborhood density can be explained if one assumes that frequency is tantamount to the number of times a word is encountered. In this way, word frequency “neutralize(s) the effect of neighborhood density” (p. 215), because a child who receives repeated exposure to a word (i.e., high frequency) will be more apt to learn the word irrespective of its neighborhood density.

In the present study, children stuttered on words that were lower in frequency than their fluently produced words. However, relative to the typically used standard for classifying words as high or low frequency (high: ≥100 per million; low: <100 per million; e.g., Morrisette & Gierut, 2002), both the stuttered and fluently produced words would seem to be sufficiently high in mean frequency (M = 6363.65 and 11992.17, respectively) for the effects of neighborhood density to be reduced. The fact that the children tended to produce more high frequency words is not surprising, considering that the (a) word samples were obtained from a naturalistic play setting in which word frequency was one of several dependent variables; (b) children were between the ages of 3;0 and 5;2, a time during which early acquired words, which tend to be high in frequency (Storkel, 2004), are more likely to occur in speech; and (c) the majority (71.4%) of the words sampled in this study were function words, which tend to be higher in frequency than content words (Pulvermüller, 1999). In contrast, previous studies that have reported neighborhood density effects in children have controlled for word frequency and focused on content words (e.g., Storkel, 2001). Thus, it is possible that neighborhood density effects were not observed in the present study due to the interfering effects of word frequency. One way in which this hypothesis could be tested is by examining the effect of neighborhood density in the speech of older children and adults who stutter, as they would presumably have more low frequency words in their lexicons.

The Role of Neighborhood Frequency

As hypothesized, findings revealed that the phonological neighbors of children's stuttered words were significantly lower in frequency of occurrence than the neighbors of their fluently produced words. This finding is consistent with several studies from the speech production literature that have reported that words with low neighborhood frequencies are more susceptible to malapropisms (Vitevitch, 1997), word-finding errors (Newman & German, 2002), and TOT states (Harley & Bown, 1998; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003) than words with high neighborhood frequencies (cf. Gordon, 2002; Vitevitch, 2002b).

One way in which the facilitative effects of neighborhood frequency observed in the present study could be accounted for comes from speech production accounts of the effects of neighborhood frequency on the speed and accuracy of word production (see the Introduction; Vitevitch, 1997; Vitevitch & Sommers, 2003). According to these accounts, words with low neighborhood frequencies receive less activation from within the phonological lexicon, increasing the likelihood that they will be less than completely retrieved. This could conceivably make them more susceptible not only to speech errors, but also to fluency breakdowns, which take the form of frequent repetitions, prolongations, or pauses. In contrast, words with high frequency neighbors would presumably be more resistant to fluency disruptions, because they receive more activation from their phoneme sharing neighbors.

Phonological Neighborhood and Word Frequency Effects on Stuttering Types

Findings supported the hypothesis that children's words containing part-word repetitions would be lower in frequency and neighborhood frequency than their fluently produced words. As expected, children's words containing sound prolongations also were lower in frequency than their fluently produced words, but the predicted effect of neighborhood frequency on these stuttering-like disfluencies was not statistically significant, although the trend was in the predicted direction. Furthermore, contrary to initial expectations, neighborhood density did not have a significant influence on the production of either part-word repetitions or sound prolongations. The hypothesis that children's productions of single-syllable word repetitions would not be influenced by word frequency or neighborhood variables was also supported, but tempered by the fact that significance was almost achieved for the effects of word frequency and power was low for neighborhood frequency. Nevertheless, these findings generally indicate that word frequency and neighborhood variables do have an influence on the type of stuttering-like disfluency produced by young CWS. However, in what is perhaps of greater interest, findings seem to provide some support for the notion that different stuttering-like disfluencies may reflect disruptions at different levels of planning for speech production, an issue discussed immediately below.

Part-Word Repetitions and Sound Prolongations May Reflect Disruption in Word-Form Retrieval

The assumption that different stuttering-like disfluency types originate in the disruption of different stages of planning for speech production is supported by findings from studies that have examined the locus of lexical variable effects, as well as by studies that have yielded information concerning the source of speech error disruptions. In this respect, researchers have posited that the locus of the frequency effect in speech production is at the level of word-form retrieval (Dell, 1990; Garrett, 2001; Griffin & Bock, 1998; Jescheniak & Levelt, 1994; Newman & German, 2005). It also has been maintained that word frequency primarily affects speech errors that involve the sounds of words, as evidenced by the fact that phonological errors are more likely to occur on low frequency words than semantic errors (Harley & MacAndrew, 2001; Stemberger & MacWhinney, 1986). Thus, because part-word repetitions were found to be sensitive to the effects of frequency and neighborhood frequency, it would seem to point to the word-form level as a potential locus of difficulty for these stuttering-like disfluencies.

The case for sound prolongations, however, is not as straightforward. Like part-word repetitions, words containing sound prolongations were significantly lower in frequency than fluently produced words, which would lead one to speculate that these stuttering-like disfluencies may originate at the level of word-form retrieval. Unlike part-word repetitions, however, neighborhood frequency failed to have a significant influence on sound prolongations, which therefore casts doubt on this speculation. Statistical power to achieve significance in this latter analysis was low, most likely due to the small sample size (n = 6) and the relatively large amount of variability in neighborhood frequency values, especially for the control words. Thus, the question of whether the word-form level can be implicated in the production of sound prolongations is not clear from the present findings, a situation that could, perhaps, be remedied in future studies by employing a larger sample of children with a larger corpus of sound prolongations.

One problem with this speculation is that evidence also suggests that neighborhood density has its effect on the ease with which word-form representations are accessed in speech production (Vitevitch et al., 2004). If part-word repetitions, and perhaps sound prolongations, represent difficulty at the level of word-form retrieval, then neighborhood density should have influenced these stuttering-like disfluencies. The present findings, however, are not unlike those of German and Newman (2004), who reported that word-form errors were predicted by neighborhood density and phoneme errors by frequency and neighborhood frequency. They suggested that phoneme errors were more likely to occur on words that were low in frequency and neighborhood frequency, because these words also tend to have less common phonological segments, making them more vulnerable to phoneme errors. Thus, if one assumes that neighborhood density affects word-form representation and the frequency variables affect phonological segments, then the fact that part-word repetitions and sound prolongations were susceptible to the effects of frequency variables but not neighborhood density can be more easily reconciled. This possibility could be assessed in future research by examining the extent to which pho-notactic probability, which refers to the frequency with which different sound segments and segment sequences occur in the lexicon (see Edwards, Beckman, & Munson, 2004; Jusczyk et al., 1994; Vitevitch, 2002a; Vitevitch et al., 2004), influences the production of these stuttering-like disfluencies.

Single-Syllable Word Repetitions May Reflect Disruption in Other Processing Levels

The finding that words containing single-syllable word repetitions could not be significantly distinguished from those that were fluently produced suggests that the locus of difficulty for these stuttering-like disfluencies may reside at some level other than that of the word form (see German & Newman, 2004, for similar speculation with respect to patterns of word-finding difficulties in school-age children). If words containing single-syllable word repetitions had their origin in disruption at the word-form level, then these stuttering-like disfluencies should have been susceptible to the effects of word frequency, neighborhood density, and/or neighborhood frequency. The theoretical significance of these findings must be tempered by the fact that statistical power for these analyses was low and, at the very least, marginal significance was obtained for the effect of word frequency. Nevertheless, if these findings do hold true, it is tempting to speculate that the most likely candidate for the origin of single-syllable word repetitions may be at the level of lemma retrieval. One means of testing this assumption would be to examine the effect of other lexical variables (e.g., imageability) on the production of single-syllable word repetitions, which are presumed to have their effect on lexical aspects of word retrieval (see Harley & MacAndrew, 2001).

Implications for the Covert Repair Hypothesis and Other Theories of Stuttering

As will be recalled, the covert repair hypothesis (CRH) is a psycholinguistic account of stuttering that suggests that both stuttering and normal disfluency represent a “covert repair reaction” to internal speech errors (Kolk & Postma, 1997; Postma & Kolk, 1993). The CRH makes two assumptions of interest to the present study: (a) stuttering should be constrained by the same variables as speech errors, and (b) different combinations of internal errors and covert repair strategies result in different types of stuttered disfluency. Findings from this study provide equivocal support for the first assumption. While effects of word frequency and neighborhood frequency on stuttering were commensurate with those of speech error studies, neighborhood density did not have the same predicted effect. It may be that with a larger sample size, power may increase sufficiently enough so as to better detect differences in neighborhood density between stuttered and control words, if present in the data. In the meantime, however, there would appear to be less than full support for the notion of complete congruence between linguistic factors that influence speech errors and those that influence stuttering. As will be recalled, the CRH posits that errors at the phoneme level result in part-word repetitions or sound prolongations, while lexical errors lead to single-syllable word repetitions. Thus, with respect to the second assumption, the present findings provide some preliminary support for the CRH in terms of the locus of disruption presumed to underlie these stuttering-like disfluencies. Specifically, the present findings suggest that difficulties at the level of phonological processing might result in part-word repetitions or sound prolongations, whereas difficulties at some other level, such as lexical processing, may result in single-syllable word repetitions.

Considering the methodological limitations of this study, speculation based on these findings is far from conclusive, and further research is clearly needed to provide more tenable support for these CRH assumptions, if they do prove genuine. Furthermore, the present findings do not resolve the question of what underlying disruptions are actually involved in stuttering—for example, whether covert repair processes are involved, as suggested by the CRH, or whether some other source of disruption, such as a lack of integrity of phonological and/or lexical representations, is involved. In addition, findings from this study do not explicitly address the question of whether individuals who stutter exhibit a phonological processing delay or deficit, the notion of which is essentially the hallmark of the CRH. The present findings do, however, provide preliminary support for the supposition that some individuals who stutter may have transitory difficulties in phonological processing (or in more than one linguistic process) related to the moment of stuttering, as evidenced by the fact that word frequency and neighborhood variables had differential effects on stuttered disfluencies.

The CRH was used as a “springboard” for the present study, because it makes specific predictions about (a) the impact of linguistic factors on speech errors and stuttering, and (b) potential areas of disruption in linguistic planning that may underlie stuttering-like disfluency types. Data from this study, however, can be broadly interpreted in accordance with several other psycholinguistic-oriented theories of stuttering. For example, the neuropsycholinguistic theory of stuttering (NTS; Perkins et al., 1991) asserts that stuttering occurs as a result of dyssynchrony in the neural systems responsible for the timely integration of segmental content within suprasegmental syllable frames. The authors of the NTS generated a number of hypotheses that are difficult to empirically assess (see Packman & Attanasio, 2004, for review), but insofar as the psycholinguistic component is concerned, the present findings do provide some general support for the notion that at least some stuttering events may be localized to disruption at the level of phonological processing.

The present findings can also be loosely interpreted within the context of another recently developed theory of stuttering, the EXPLAN theory (Howell, 2004; Howell & Au-Yeung, 2002). According to the EXPLAN theory, fluency failures result from disruption in the interaction or timing between speech-language planning (syntactic, lexical, and phonetic levels) and motor execution processes. More specifically, fluency breakdowns are hypothesized to occur when a speaker finishes executing one linguistic plan and the next plan is not ready for execution. A plan may not be ready for execution because the word is too linguistically complex or speech is initiated too rapidly. In either case, the speaker will presumably repeat the previously executed word(s) or insert a filled or unfilled pause to “buy time” for further processing. Although the theory emphasizes the phonetic properties of words (as measured by consonant strings, age of consonant acquisition, and/or word length) as primary indicators of linguistic complexity, other linguistic demands, such as those associated with lexical processes, can also influence the difficulty of a word. If a word is, for example, high in complexity, then more time will be needed for planning and, thus, the probability that a fluency breakdown will occur is increased. For young children, the problematic word is not the word (most likely a function word) that is being stuttered on, but rather the subsequent word (most likely a content word) that the child is still planning and not yet ready to execute. Thus, the theory predicts that young children will produce single-syllable word repetitions and hesitations “on the easy [italics added] words before the content word” (Howell, 2004, p. 128).

In general, the present findings do not appear to provide appreciable support for some aspects of the EXPLAN theory. First, unlike the CRH, the EXPLAN theory does not assume that stuttering occurs as a result of errors in speech planning (Howell, 2004). Therefore, because stuttering is not presumed to be related to the production of errors, there would be little reason to expect that lexical factors would have the same effect on both stuttering and speech errors. The present findings, however, revealed that word frequency and neighborhood frequency have the same effect on stuttering as they do on speech errors, a finding that would not necessarily be expected to occur according to the EXPLAN theory.

Second, the EXPLAN theory predicts that young children will stutter on words (mostly function words) that are less linguistically complex or easier than subsequent content words. Although approximately three fourths of the stuttered words sampled in the study were function words, the stuttered words were still significantly lower in frequency and neighborhood frequency than the fluently produced words, suggesting that the stuttered words were, in fact, more difficult. According to the EXPLAN theory, one might have logically predicted that the stuttered words would have been easier or at least not significantly different from the fluent control words, a prediction that was not upheld in the present study. Of course, the EXPLAN theory posits that stuttered words should be easier than subsequent content words, whereas the present comparisons involved word pairs of the same grammatical class (e.g., a stuttered function word compared to the next fluently produced function word). Thus, a more accurate test of the EXPLAN theory would be to compare the neighborhood density and frequency characteristics of words that immediately follow a stuttered word to the next fluently produced word that does not follow a stuttered word and matches it in grammatical class, word length, and familiarity. If the EXPLAN theory is correct in its assumption, the words that immediately follow the stuttered words should be lower in density, frequency, and neighborhood frequency than the comparable fluently produced words.

Caveats

As is typical of most any empirical investigation dealing with human behavior, there are several issues that must be kept in mind when evaluating and interpreting the present findings. The first is that the familiarity, frequency, neighborhood density, and neighborhood frequency values of the stuttered and control words were obtained from an online database of the adult lexicon. As previously indicated, the use of this database was justified, in part, by the fact that their values have been shown to be highly comparable to those obtained from child databases (Jusczyk et al., 1994; Walley & Metsala, 1992). Nevertheless, it is clear that children are not simply miniature versions of adults, and therefore, lexical values obtained from child databases may actually yield more accurate and reliable estimates of the variables under study, which could influence the findings. It is also possible that the failure of neighborhood density to have an effect on stuttering may be related to the use of values obtained from an adult database. On the other hand, several studies have reported that the use of adult databases for child data results in the same outcome as child databases (Dale, 2001; Gierut & Storkel, 2002). Therefore, even if differences are evident in the lexicons of adults and children, it may not be of sufficient consequence to the resulting findings. In future studies, researchers may want to consider examining the effect of neighborhood density and frequency variables in CWS using values from child databases or, better yet, both child and adult databases, as this would allow one to compare findings from both databases.