Abstract

We have previously shown T cell-mediated rejection of the neu-overexpressing mammary carcinoma cells (MMC) in wild-type FVB mice. However, following rejection of primary tumors, a fraction of animals experience a recurrence of a neu antigen-negative variant (ANV) of MMC (tumor evasion model), after a long latency period. In the present study, we determined that T cells derived from wild-type FVB mice can specifically recognize MMC by secreting IFN-γ and can induce apoptosis of MMC in vitro. Neu-transgenic (FVBN202) mice develop spontaneous tumors and cannot reject it (tumor tolerance model). To dissect the mechanisms associated with rejection or tolerance of MCC tumors, we compared transcriptional patterns within the tumor microenvironment of MMC undergoing rejection with those that resisted it either because of tumor evasion/antigen-loss recurrence (ANV tumors) or because of intrinsic tolerance mechanisms displayed by the transgenic mice. Gene profiling confirmed that immune rejection is primarily mediated through activation of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) and T cell effector mechanisms. The tumor evasion model demonstrated combined activation of Th1 and Th2 with a deviation towards Th-2 and humoral immune responses that failed to achieve rejection likely because of lack of target antigen. Interestingly, the tumor tolerance model instead displayed immune suppression pathways through activation of regulatory mechanisms that included in particular the over-expression of IL-10, IL-10 receptor and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 and SOCS-3. This data provides a road-map for the identification of novel biomarkers of immune responsiveness in clinical trials.

Keywords: HER-2/neu, FVBN202, breast cancer, tumor escape, interferon stimulated genes

Introduction

Challenges in the immune therapy of cancers include a limited understanding of the requirements for tumor rejection and prevention of recurrences after successful therapy. Evaluation of T cell responses in human tumors, based predominantly on the metastatic melanoma model have clearly shown that the tumor bearing status primes systemic immune responses against tumor-associated antigens, which, however, are insufficient to induce tumor rejection (1, 2). Moreover, the experience gathered through the induction of tumor antigen-specific T cells by vaccines has shown that the frequency of tumor antigen-specific T cells in the circulation (3, 4) or in the tumor microenvironment (5, 6) does not directly correlate with successful rejection or prevention of recurrence (7). Similarly, patients with pre-existing immune responses against HER-2/neu are not protected from the development of HER-2/neu expressing breast cancers (8). Although several and contrasting reasons have been proposed to explain this paradox, two lines of thoughts summarize these hypotheses; either tolerogenic and/or immune suppressive properties of tumors may hamper T cell function (9–11) or characteristics of the tumor microenvironment could induce tumor escape and evade the anti-tumor function of an otherwise effector T cells (12, 13).

In spite of this paradoxical coexistence of tumor specific T cells and their target antigen-bearing cancer cells, recent observations in cancer patients suggest that T cells control tumor growth and mediate its rejection. Galon J et al. and others (14–16) observed that T cells modulate the growth of human colon cancer and T cell infiltration of primary lesions may forecast a better prognosis. In addition, these authors observed that tumor-infiltrating T cells in cancers with good prognosis displayed transcriptional signatures typical of activated T cells such as the expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs), IFN-γ itself and cytotoxic molecules, in particular granzyme-B (15). Similar observations were reported by others in human ovarian carcinoma (17). These important observations derived from human tissues provide novel prognostic markers but cannot address the causality of the association between T cell infiltration and natural history of cancer. Recent reports based on adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells suggest a cause-effect relationship between the administration of T cells and tumor rejection (18). However, the complexity of the therapy associated with adoptive transfer of T cells which includes immune ablation and systemic administration of IL-2 prevents a clear interpretation of this causality.

We, therefore, adopted an experimental model that could address the paradoxical relationship between adaptive immune responses against cancer antigens and rejection or persistence of antigen-bearing cancers with the intent of comparing functional signatures between the experimental model and previous human observation that could shed mechanistic information on this relationship and potentially provide novel predictive or prognostic biomarkers to be tested in the clinical settings. In this study, we compared transcriptional patterns of mammary tumors undergoing rejection to that of related tumors that evaded immune recognition through antigen loss (evasion model) or resided in tolerized transgenic mice (tolerogenic model). For this purpose, we used FVB mice that reject neu-overexpressing mammary carcinomas (MMC) because of the presence of a potent neu-specific T cell response. Although MMC are consistently rejected after a few weeks, occasionally MMC recur and in such instance they resist further immune pressure by invariably loosing HER-2/neu expression (tumor evasion model) (19, 20). Moreover, FVBN202 mice that constitutively express high levels of HER-2/neu fail to reject MMC because they cannot mount effective anti-tumor T cell responses (tolerogenic model). Thus, we compared the tumor microenvironment at salient moments of immune response/evasion/tolerance to gain, in this previously well-characterized model (19, 20), insights about the immune mechanisms leading to tumor rejection and their failure in conditions of tumor evasion or systemic tolerance. Interestingly, the tolerance model, which was expected to show tolerance, displayed immune suppression pathways through activation of regulatory mechanisms that included in particular the over-expression of IL-10, IL-10 receptor and suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1 and SOCS-3.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Wild-type FVB (Jackson Laboratories) and FVBN202 female mice (Charles River Laboratories) were used throughout these studies. FVBN202 is the rat neu transgenic mouse model in which 100% of females develop spontaneous mammary tumors by 6–10 mo of age, with many features similar to human breast cancer. These mice express an unactivated rat neu transgene under the regulation of the MMTV promoter (21). Because of the overexpression of rat neu protein, FVBN202 mice are expected to tolerate the neu antigen as self protein, and in cases where there might be a weak neu-specific immune response prior to the appearance of spontaneous mammary tumors are still well tolerated (22, 23). On the other hand, rat neu protein is seen as nonself antigen by the immune system of wild-type FVB mice, resulting in aggressive rejection of primary MMC (19, 24). The studies have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Tumor cell lines

The MMC cell line was established from a spontaneous tumor harvested from FVBN202 mice as previously described (11, 15). Tumors were sliced into pieces and treated with 0.25% trypsin at 4 °C for 12–16 h. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, washed, and cultured in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (19, 20). The cells were analyzed for the expression of rat neu protein before use. Expression of rat neu protein was also analyzed prior to each experiment and antigen negative variants (ANV) were reported accordingly (see results).

In vivo tumor challenge

Female FVB or FVBN202 mice were inoculated s.c. with MMC (4–5×106 cells/mouse). Animals were inspected twice every week for the development of tumors. Masses were measured with calipers along the two perpendicular diameters. Tumor volume was calculated by: V(volume) = L(length) × W(width)2 ÷ 2. Mice were sacrificed before a tumor mass exceeded 2000 mm3.

IFN-γ ELISA

Secretion of MMC-specific IFN-γ by lymphocytes was detected by co-culture of lymphocytes (4×106 cells) with irradiated MMC or ANV (15,000 rads) at 10:1 E:T ratios in complete medium (RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 ug/ml streptomycin) for 24 hrs. Supernatants were then collected and subjected to IFN-γ ELISA assay using a Mouse IFN-γ ELISA Set (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer protocol. Results were reported as the mean values of duplicate ELISA wells.

Flow cytometry

A three color staining flow cytometry analysis of the mammary tumor cells (106 cells/tube) was carried out using mouse anti-neu (Ab-4) Ab (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), control Ig, FITC-conjugated anti-mouse Ig (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), PE-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) at the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were finally added with annexin V buffer and analyzed at 50,000 counts with the Beckman Coulter EPICS XL within 30 min.

Microarray performance and statistical analysis

Total RNA from tumors was extracted after homogenization using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of secondarily amplified RNA was tested with the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2000 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) and amplified into anti-sense RNA (aRNA) as previously described (25, 26). Confidence about array quality was determined as previously described (27). Mouse reference RNA was prepared by homogenization of the following mouse tissues (lung, heart, muscle, kidneys and spleen) and RNA was pooled from 4 mice. Pooled reference and test aRNA were isolated and amplified in identical conditions during the same amplification/hybridization procedure to avoid possible inter-experimental biases. Both reference and test aRNA were directly labeled using ULS aRNA Fluorescent labeling Kit (Kreatech, Netherlands) with Cy3 for reference and Cy5 for test samples.

Whole genome mouse 36 k oligo arrays were printed in the Infectious Disease and Immunogenetics Section of Transfusion Medicine (IDIS), Clinical Center, National Institute of Health, Bethesda using oligos purchased from Operon (Huntsville, AL). The Operon Array-Ready Oligo Set (AROS™) V 4.0 contains 35,852 longmer probes representing 25,000 genes and about 38,000 gene transcripts and also includes 380 controls. The design is based on the Ensembl Mouse Database release 26.33b.1, Mouse Genome Sequencing Project, NCBI RefSeq, Riken full-length cDNA clone sequence, and other GenBank sequence. The microarray is composed of 48 blocks and one spot is printed per probe per slide. Hybridization was carried out in a water bath at 42°C for 18–24 hours and the arrays were then washed and scanned on a Gene Pix 4000 scanner at variable PMT to obtain optimized signal intensities with minimum (< 1% spots) intensity saturation.

Resulting data files were uploaded to the mAdb databank (http://nciarray.nci.nih.gov) and further analyzed using BRBArrayTools developed by the Biometric Research Branch, National Cancer Institute (28) (http//:linus.nci.nih.gov/BRB-ArrayTools.html) and Cluster and Treeview software (29). The global gene-expression profiling consisted of 18 experimental samples. Subsequent filtering (80% gene presence across all experiments and at least 3-fold ratio change) selected 11,256 genes for further analysis. Gene ratios were average-corrected across experimental samples and displayed according to uncentered correlation algorithm (30).

Statistical analysis

Rate of tumor growth was compared statistically by un-paired Student’s t test. Unsupervised analysis was performed for class confirmation using the BRBArrayTools and Stanford Cluster program (30). Class comparison was performed using parametric unpaired Student’s t test or three-way ANOVA to identify differentially-expressed genes among tumor-bearing, tumor-rejection and relapse groups using different significance cut-off levels as demanded by the statistical power of each comparison. Statistical significance and adjustments for multiple test comparisons were based on univariate and multivariate permutation test as previously described (31, 32).

Results

T cell-mediated rejection of MMC and relapse of its neu antigen negative variant, ANV, in wild-type FVB mouse

Wild-type FVB mice are capable of rejecting MMC within 3 wk because of specific recognition of rat neu protein by their T cells as opposed to their transgenic counterparts, FVBN202, that tolerate rat neu protein and fail to reject MMC (19, 24). In order to determine whether aggressive rejection of primary MMC by T cells may lead to relapse-free survival in wild-type FVB mice, we performed follow-up studies. Animals (n=15) were challenged with MMC by s.c. inoculation at the right groin. Animals were then monitored for tumor growth twice weekly. All mice rejected MMC within 3 wk after the challenge (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, a fraction of these animals (8 out of 15 mice) developed recurrent tumors at the site of inoculation. These relapsed tumors had lost neu expression under immune pressure (19, 24). Relapsed-free groups were maintained as breeding colonies and did not show any relapse during their life span. Splenocytes of FVB mice secreted IFN-γ in the presence of MMC only (2200 pg/ml) while no appreciable IFN-γ was detected when lymphocytes were stimulated with ANV (110 pg/ml). No IFN-γ was secreted by splenocytes or tumor cells alone (data not shown).

T cells derived from wild-type FVB mice will induce apoptosis in MMC

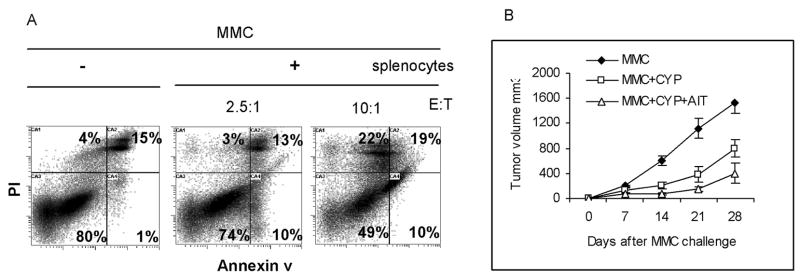

In order to determine whether neu-specific recognition of MMC by T cells may induce apoptosis in MMC, in vitro studies were performed. Splenocytes of naïve FVB mice were stimulated with irradiated MMC for 24 hrs followed by 3 day expansion in the presence of IL-2 (20 U/ml). Lymphocytes were then co-cultured with MMC (E:T ratio of 2.5:1 and 10:1) for 48 hrs in the presence of IL-2 (20 U/ml). Control wells were seeded with MMC or splenocytes alone in the presence of IL-2. Cells (floaters and adherents) were collected and subjected to a three color flow cytometry analysis using mouse anti-rat neu Ab (Ab-4), PE-conjugated anti mouse Ig, control Ig, annexin V, and PI. Gated neu positive cells were analyzed for the detection of annexin V+ and PI+ apoptotic cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, 80% of MMC were annexin V− and PI− in the absence of lymphocytes while only 49% of MMC were annexin V− and PI− in the presence of lymphocytes at 10:1 E:T ratio. At a lower E:T ratio (2.5:1) there was a slight dropping in the number of viable MMC (from 80% to 74%), but marked increase in the number of early apoptotic cells (annexin V+/PI−) from 1% to 10%. At a higher E:T ratio (10:1) early (Annexin V+/PI−) or late (annexin V+/PI+) apoptotic cells and necrotic cells (annexin V−/PI+) were markedly increased.

Figure 1. T cells derived from wild-type FVB mice will induce apoptosis in MMC in vitro but fail to reject MMC in FVBN202 mice following AIT.

A) Flow cytometry analysis of MMC after 24 hrs culture with splenocytes of FVB mice following three color staining. Gated neu positive cells were analyzed for the detection of annexin V+ and PI+ apoptotic cells. Data are representative of quadruplicate experiments. B) Donor T cells were enriched from the spleen of FVB mice using nylon wool column following the rejection of MMC. FVBN202 mice (n=4) were injected with CYP followed by inoculation with MMC (4 × 106 cells/mouse), and tail vein injection of donor T cells. Control groups were challenged with MMC in the presence or absence of CYP treatment. Tumor growth was monitored twice weekly.

Adoptive immunotherapy (AIT) of FVBN202 mice using T cells derived from wild-type FVB donors failed to reject MMC

In order to determine whether T cells of FVB mice with neu-specific and anti-tumor activity may protect FVBN202 mice against MMC challenge, AIT was performed. Using nylon wool column, T cells were enriched from the spleen of FVB donor mice following the rejection of MMC. FVBN202 recipient mice were injected i.p. with cyclophosphamide (CYP; 100 μg/g) in order to deplete endogenous T cells. After 24 hrs animals were challenged with MMC tumors (4 × 106 cells/mouse). Four-five hrs after tumor challenge, donor T cells were transferred into FVBN202 mice (6 × 107 cells/mouse) by tail vein injections. Control FVBN202 mice were challenged with MMC in the presence or absence of CYP treatment. Animals were then monitored for tumor growth. As shown in Fig. 1B, CYP treatment of animals resulted in retardation of tumor growth in FVBN202 mice as expected. Student’s t test analysis on days 14, 21, and 28 post-challenge showed significant differences between these two groups (P= 0.005, 0.007, 0.01, respectively). Adoptive transfer of neu-specific effector T cells from MMC-sensitized FVB mice into CYP-treated FVBN202 groups did not significantly inhibit tumor growth compared to CYP-treated control groups (P > 0.05). Adoptive transfer of neu-specific effector T cells from untreated FVB mice into CYP-treated FVBN202 groups showed similar trend of tumor growth (data not shown). These experiments suggest that T cell responses associated with MMC rejection in wild-type FVB mice (19) may represent an epiphenomenon with no true cause-effect relationship or that FVBN202 mice retain tolerogenic properties in spite of CYP treatment that can hamper the function of potentially effective anti-cancer T cell responses. We favor the second hypothesis based on our previous depletion experiments that demonstrated the requirement of endogenous effector T cells of FVB mice for rejection of MMC tumors (19).

Genetic signatures defining rejection or tolerance of MMC tumors

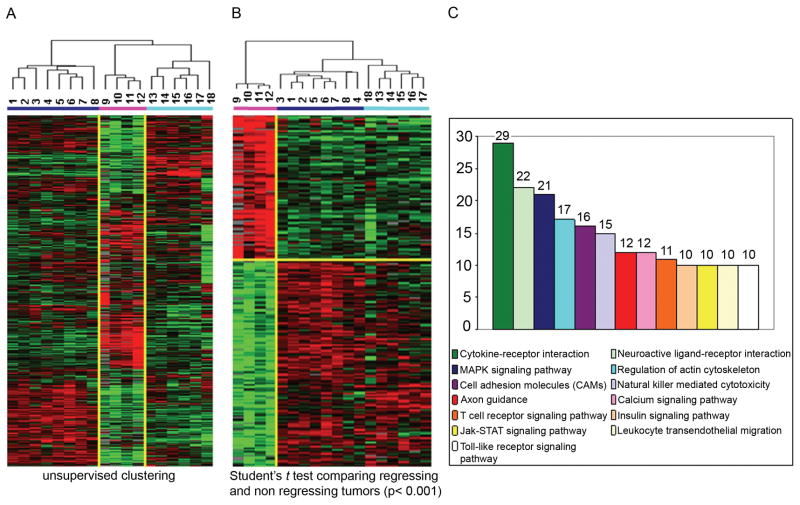

To ascertain whether the presence of neu-specific effector T cells may trigger a cascade of events which may determine success or failure in tumor rejection, wild-type FVB and FVBN202 mice were inoculated with MMC. Historically, all FVB mice reject MMC, however a fraction develop a latent tumor relapse. In contrast, FVBN202 mice fail to reject transplanted MMC. Ten days after the tumor challenge, transplanted MMC tumors were excised and RNAs were extracted from both FVB and FVBN202 carrier mice based on the presumption that the biology of the former would be representative of active tumor rejection and that of the latter representative of tumor tolerance. Thus, the timing of tumor harvest was chosen to capture transcriptional signatures associated with the active phase of the tumor rejection process in wild-type FVB mice in comparison with the corresponding tolerance of spontaneous mammary tumors in the FVBN202 mice. We speculated that this comparison would allow distinguishing whether tolerance was due to inhibition of T cell function within the tumor microenvironment of spontaneous mammary tumors or to a complete absence of such responses. To enhance the robustness of the comparison, a similar analysis was performed extracting total RNA from spontaneous tumor in FVBN202 mice. In addition, RNA was extracted from MMC tumors in wild-type FVB mice that experienced tumor recurrence following the initial rejection of MMC. This second analysis allowed the comparison of mechanisms of tumor evasion in the absence of known tolerogenic effects. Micro array analyses were then performed on the amplified RNA (aRNA) extracted from these tumors using 36k oligo mouse arrays. Hence, genes considered as differentially expressed in the study groups could either represent MMC tumor cells or host cells infiltrating the tumor site. Probes with missing values greater than 80% or a change less than 3 fold were excluded from further analysis. Unsupervised clustering demonstrated outstanding differences among the three experimental groups (Fig. 2A). Genes of spontaneous mammary tumors (samples 13, 15, 16, 17) clustered closely to those of transplanted MMC (14 and 18) excised from FVBN202 mice suggesting that the biology of MMC tumors remains comparable between these two experimental models of tolerance. Global transcriptional patterns associated with tumor relapse (samples 1–8) were instead clearly differed from those of spontaneous mammary tumors or MMC transplanted in tolerant FVBN202 mice suggesting that a completely different biological process was at the basis of tumor evasion through loss of target antigen expression. Finally, MMC tumors undergoing rejection (samples 9–12) were clearly separated from the either kind of non-regressing tumors.

Figure 2. Gene expression profiling and gene oncology pathway analyses in tumor regressing and tumor non-regressing groups.

(A) Unsupervised cluster visualization of genes differentially expressed among regressing tumors (pink bar) and non regressing tumors (blue bar = evasion model; turquoise bar = tolerogenic model). MMC tumors were harvested 10 days after challenge and hybridized to 36k oligo mouse arrays. 11256 genes with at least 3fold ratio change and 80% presence call among all samples were projected using log2 intensity. (B) Supervised cluster analysis (Student t test, p< 0.001 and fold change >3) comparing regressing tumors (pink bar) and non regressing tumors (blue bar = evasion model; turquoise bar = tolerogenic model). 2449 differentially expressed genes have been selected for further analysis. (C) Gene Ontology databank was queried to assign genes to functional categories and up-regulated genes within the tumor regression group to functional categories.

Biomarkers of rejection

Our first class comparison searched for differences between the four tumor samples undergoing rejection and the rest of the MMC tumors whether belonging to the tolerogenic or the evasion process. This approach followed the exclusion principle whereby factors determining the occurrence of a phenomenon should be discernible from unrelated ones independent of the causes preventing its occurrence. An unpaired Student t test with a cut-off set at p < 0.001 identified 2,449 genes differentially expressed between regressing and non regressing tumors (permutation p value = 0) of which 1,003 genes were up-regulated in regressing tumors clearly distinguishing the two categories (Fig. 2B). Of those, a large number were associated with immune regulatory functions. Gene Ontology databank was queried to assign genes to functional categories and up-regulated pathways were ranked according to the number of genes identified by the study belonging to each category (Fig. 2C). The top categories of genes that were up-regulated in primary rejected MMC tumors were Cytokine-Cytokine interaction, MAPK signaling, Cell Adhesion related transcripts and axon guidance, T cell receptor, JAK-STAT and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. NK cell mediated cytotoxicity and calcium signaling pathways were also enriched in up-regulated genes. In contrast, very little evidence of immune activation could be observed in either category of non-regressing tumors suggesting that lack of immune rejection is due to absent or severely hampered immune responses in the tumor microenvironment independent of the mechanisms leading to this resistance.

To better describe the immununological pathways associated with tumor regression we organized genes with immune function into three categories including chemokines, IFN-α2, IFN-γ and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Table 1), and cytokines and signaling molecules (Table 2). From this analysis, it became clear that T cell infiltration into tumors was associated with activation of various pathways leading to the expression of IFN-α, IFN-γ and several ISGs including interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-4, IRF-6 and STAT-2. In addition, several cytotoxic molecules were overexpressed including calgranulin-a, calgranulin-b and granzyme-B; all of them representing classical markers of effector T cell activation in humans (10) and in mice (33). Thus, tumor rejection in this model clearly recapitulates patterns observed in various human studies in which expression of ISGs is associated with the activation of cytotoxic mechanisms among which granzyme-B appears to play a central role.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed Interferon Stimulating Genes (ISGs), chemokines and their receptors

| CXC Chemokines and receptors | Mouse | Human | rejection | controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cxcl2 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 2 | GRO; MIP-2;KC? | GROξ;MGSA-ξ | CXCR2 | 14.54 | 0.44 |

| Cxcl1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 | GRO; MIP-2;KC? | GROa;MGSA-ξ | CXCR2>1 | 5.40 | 0.70 |

| Cxcl11 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 11 | I-TAC | I-TAC | CXCR3 | 3.93 | 0.68 |

| CC Chemokines and receptors | ||||||

| Ccl1 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 1 | TCA-2;P500 | I-309 | CCR8 | 2.15 | 0.80 |

| Ccl4 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | MIP-1ξ | MIP-1ξ | CCR5 | 5.06 | 0.63 |

| Ccl5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | RANTES | RANTES | CCR1;3,5 | 5.42 | 0.62 |

| Ccl5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | RANTES | RANTES | CCR1;3,5 | 3.96 | 0.67 |

| Ccl6 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6 | C10;MRP-1 | Unknown | Unknown | 3.79 | 0.68 |

| Ccl8 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | MCP-2 | MCP-2 | CCR3;5 | 5.94 | 0.60 |

| Ccl9 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 9 | MRP-2;CCF18;MIP-1ξ | Unknown | CCR1 | 6.72 | 0.58 |

| Ccl11 | small chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 | Eotaxin | Eotaxin | CCR3 | 4.34 | 0.64 |

| Ccl22 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 22 | ABCD-1 | MDC/STCP-1 | CCR4 | 4.08 | 0.74 |

| Ccrl2 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor-like 2 | CCL2,7,12,13,16 | 6.58 | 0.62 | ||

| Ccr10 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 10 | CCL27,28 | 2.22 | 0.83 | ||

| Cklf | chemokine-like factor | 2.86 | 0.74 | |||

| Darc | Duffy blood group, chemokine receptor | 2.83 | 0.86 | |||

| Cklf | chemokine-like factor, transcript variant 1 | 2.82 | 0.74 | |||

| Interferon Stimulated Genes (ISGs) | ||||||

| Ifna2 | interferon alpha 2 | 2.91 | 0.80 | |||

| Ifng | interferon gamma | 2.89 | 0.72 | |||

| Ifi202b | interferon activated gene 202B | 6.05 | 0.60 | |||

| Ifi27 | interferon, alpha-inducible protein 27 | 4.68 | 0.64 | |||

| Ifi204 | interferon activated gene 204 | 4.14 | 0.67 | |||

| Ifitm1 | interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 | 3.73 | 0.75 | |||

| Irf6 | Interferon regulatory factor 6 | 3.59 | 0.76 | |||

| Ifit1 | interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 | 3.33 | 0.77 | |||

| Irf4 | interferon regulatory factor 4 | 2.97 | 0.73 | |||

| Mx1 | myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 1 | 2.63 | 0.76 | |||

| Stat2 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 | 2.35 | 0.78 | |||

| Stat6 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 | 2.14 | 0.80 | |||

| Irf2bp1 | interferon regulatory factor 2 binding protein 1 | 0.29 | 1.42 |

Table 2.

Differentially expressed cytokines and signaling molecules

| Genes up-regulated in the rejection model | Genes down-regulated in the rejection model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Description | reject | contr. | Symbol | Description | reject | contr. |

| Interleukins and receptors | |||||||

| Il1a | interleukin 1 alpha | 2.71 | 0.81 | ||||

| Il1b | interleukin 1 beta | 8.91 | 0.54 | ||||

| Il1f9 | interleukin 1 family, member 9 | 1.97 | 0.82 | ||||

| Il5 | interleukin 5 | 1.64 | 0.87 | ||||

| Il7 | interleukin 7 | 3.11 | 0.84 | ||||

| Il17f | interleukin 17F | 3.86 | 0.68 | ||||

| Il31 | interleukin 31 | 2.16 | 0.80 | ||||

| 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Il1rap | interleukin 1 receptor accessory protein, transcript variant 2 | 3.56 | 0.70 | ||||

| Il2rg | interleukin 2 receptor, gamma chain | 1.75 | 0.85 | ||||

| Il7r | interleukin 7 receptor | 2.46 | 0.88 | ||||

| Il23r | interleukin 23 receptor | 7.38 | 0.63 | ||||

| Il17rb | interleukin 17 receptor B | 4.46 | 0.65 | ||||

| 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic molecules | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Gzmb | granzyme B | 1.90 | 0.83 | ||||

| Gzmb | granzyme B | 1.57 | 0.88 | ||||

| Ctla2a | cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 2 alpha | 3.60 | 0.69 | ||||

| Klra9 | killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily A, member 9 | 1.95 | 0.87 | ||||

| Klrd1 | killer cell lectin-like receptor, subfamily D, member 1 | 7.36 | 0.57 | ||||

| Fasl | Fas ligand (TNF superfamily, member 6) | 2.78 | 0.75 | Tnfaip1 | tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 1 | 0.51 | 1.21 |

| Tnfsf11 | tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 | 2.56 | 0.80 | ||||

| Tnfrsf1b | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 1b | 2.21 | 0.83 | Tnfrsf12a | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a | 0.14 | 1.52 |

| Tnfrsf4 | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 4 | 2.77 | 0.73 | Ngfrap1 | nerve growth factor receptor (TNFRSF16) associated protein 1 | 0.38 | 1.15 |

| Toll-like receptors and lymphocyte signaling | |||||||

| Tlr4 | toll-like receptor 4 | 2.14 | 0.80 | ||||

| Tlr6 | toll-like receptor 6 | 2.98 | 0.86 | ||||

| Il4i1 | interleukin 4 induced 1 | 3.34 | 0.77 | ||||

| Alcam | activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule | 2.12 | 0.81 | ||||

| Bcl2a1c | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 related protein A1c | 3.41 | 0.70 | ||||

| Itk | IL2-inducible T-cell kinase | 2.63 | 0.76 | Ilf3 | interleukin enhancer binding factor 3, transcript variant 2 | 0.44 | 1.27 |

| Ebf4 | early B-cell factor 4 | 6.32 | 0.75 | ||||

| Ly6a | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus A | 2.83 | 0.74 | ||||

| Ly6c | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C | 3.18 | 0.72 | Ly6e | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | 0.22 | 1.53 |

| Ly6f | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus F | 3.62 | 0.67 | Ly6e | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E | 0.47 | 1.18 |

| Ly6f | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus F | 2.41 | 0.78 | Btla | B and T lymphocyte associated, transcript variant 2 | 0.38 | 1.32 |

| Lck | lymphocyte protein tyrosine kinase | 2.26 | 0.79 | Bcap31 | B-cell receptor-associated protein 31 | 0.34 | 1.36 |

| Tagap | T-cell activation Rho GTPase-activating protein | 2.36 | 0.78 | Tiam2 | T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 2 | 0.47 | 1.24 |

| Tlx1 | T-cell leukemia, homeobox 1 | 7.36 | 0.65 | Ikbkap | inhibitor of kappa light polypeptide enhancer in B-cells | 0.44 | 1.27 |

| Tcl1b1 | T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 1B, 1 | 2.37 | 0.78 | ||||

| Nkrf | NF-kappaB repressing factor | 3.90 | 0.75 | ||||

| Nkiras2 | NFKB inhibitor interacting Ras-like protein 2 | 2.48 | 0.82 | Irak1bp1 | interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 binding protein 1 | 0.33 | 1.26 |

| Nfkbiz | Nfkb light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta | 3.83 | 0.68 | Irak1 | interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | 0.31 | 1.40 |

| Nfat5 | nuclear factor of activated T-cells 5, transcript variant b | 3.34 | 0.71 | ||||

| FC-type receptors | |||||||

| Lilrb4 | Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor, subfamily B, member 4 | 3.60 | 0.74 | ||||

| Mgl1 | macrophage galactose N-acetyl-galactosamine specific lectin 1 | 6.23 | 0.59 | ||||

| Mgl2 | macrophage galactose N-acetyl-galactosamine specific lectin 2 | 2.25 | 0.79 | ||||

| Msr1 | macrophage scavenger receptor 1 | 2.78 | 0.80 | ||||

| Immunoglobulins | |||||||

| Igh-6 | Immunoglobulin heavy chain 6 | 7.43 | 0.56 | ||||

| Igh-6 | Immunoglobulin heavy chain 6 (heavy chain of IgM) | 2.39 | 0.78 | ||||

| Igj | immunoglobulin joining chain | 2.86 | 0.74 | ||||

| Igk-V28 | Immunoglobulin kappa chain variable 28 | 2.82 | 0.79 | ||||

| Igl-V1 | Immunoglobulin lambda chain, variable 1 | 3.69 | 0.76 | ||||

| Igl-V1 | Immunoglobulin lambda chain, variable 1 | 2.03 | 0.82 | ||||

| Igkv4–90 | Immunoglobulin light chain variable region | 1.82 | 0.84 |

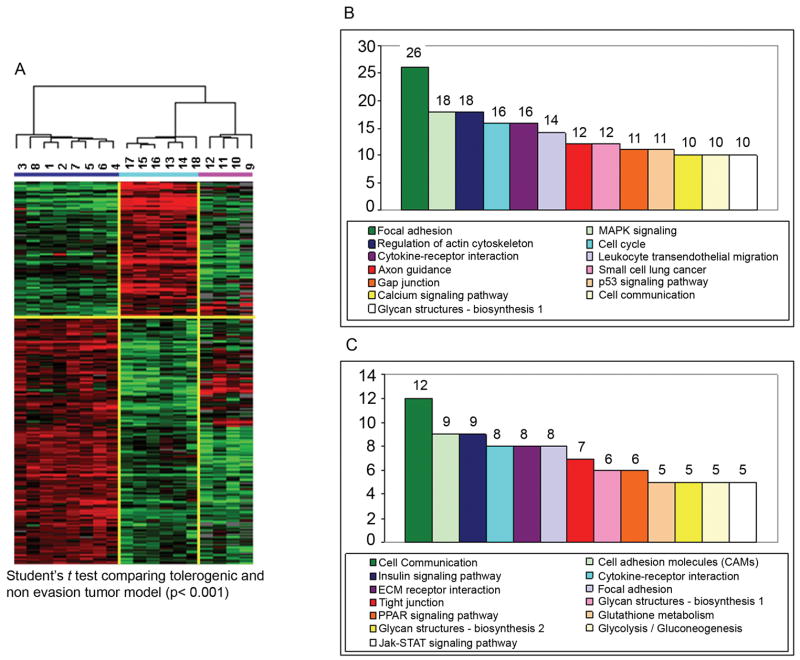

Is there a difference between signatures of immune evasion and immune tolerance?

As shown in Table 3, the high expression of IL-10 and the IL-10 receptor-β chain concordant with IRF-1 in the tolerogenic model strongly suggests the presence of regulatory mechanism within the microenvironment of MCC-bearing FVBN202 mice. Preferential expression of SOCS-1 and SOCS-3 in the microenvironment of MMC tumors of FVBN202 mice also strongly suggest a marked activation of regulatory functions present in the tolerized host (Table 3).

Table 3.

Manually selected genes with immunological function based on supervised comparison of evasion and tolerogenic tumor models and tumor rejection model

| Symbol | Description | evasion | tolerogenic | rejection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemokines | ||||

| Ccl2 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | 2.304 | 0.614 | 0.392 |

| Ccl4 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | 1.899 | 0.478 | 0.838 |

| Ccl6 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 6 | 2.525 | 0.536 | 0.400 |

| Ccr7 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 | 1.441 | 0.696 | 0.829 |

| Cxcl10 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | 2.341 | 0.781 | 0.264 |

| Cxcl9 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 9 | 1.440 | 0.354 | 2.288 |

| Xcl1 | chemokine (C motif) ligand 1 | 4.913 | 0.279 | 0.282 |

| Cx3cl1 | chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1 | 5.120 | 0.393 | 0.155 |

| Interleukins and signaling | ||||

| Il12b | interleukin 12b | 1.768 | 0.866 | 0.397 |

| Il13 | interleukin 13 | 1.475 | 0.779 | 0.669 |

| Il17d | interleukin 17D | 1.690 | 0.674 | 0.633 |

| Il23r | interleukin 23 receptor | 2.048 | 0.457 | 0.772 |

| Il2rg | interleukin 2 receptor, gamma chain | 1.798 | 0.742 | 0.484 |

| Il4 | interleukin 4 | 2.342 | 0.497 | 0.521 |

| Il4i1 | interleukin 4 induced 1 | 2.290 | 0.701 | 0.325 |

| Il6 | interleukin 6 | 1.105 | 0.504 | 2.291 |

| Il7r | interleukin 7 receptor | 1.218 | 0.439 | 3.063 |

| Il9 | interleukin 9 | 1.711 | 0.801 | 0.477 |

| Tlr11 | toll-like receptor 11 | 2.656 | 0.435 | 0.540 |

| Blnk | B-cell linker | 1.457 | 0.749 | 0.726 |

| Bok | Bcl-2-related ovarian killer protein | 2.071 | 0.432 | 0.822 |

| Vpreb3 | pre-B lymphocyte gene 3 | 2.712 | 0.148 | 2.398 |

| Lcp2 | lymphocyte cytosolic protein 2 | 1.640 | 0.588 | 0.824 |

| Ly6d | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D | 4.093 | 0.223 | 0.567 |

| Nfkb1 | nfkb light chain gene enhancer 1, p105 | 1.737 | 0.785 | 0.477 |

| Pias2 | Protein inhibitor of activated STAT 2 | 1.336 | 0.502 | 1.458 |

| Pias3 | protein inhibitor of activated STAT 3 | 1.763 | 0.828 | 0.427 |

| Stat4 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 | 1.579 | 0.685 | 0.630 |

| Il10 | interleukin 10 | 0.788 | 2.528 | 0.400 |

| Il1r2 | interleukin 1 receptor, type II | 0.804 | 2.504 | 0.391 |

| Il10rb | interleukin 10 receptor, beta | 0.422 | 2.839 | 1.174 |

| Socs1 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | 0.566 | 4.683 | 0.308 |

| Socs3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 0.621 | 1.751 | 1.120 |

| Bak1 | BCL2-antagonist/killer 1 | 0.663 | 2.698 | 0.514 |

| Lsp1 | lymphocyte specific 1 | 0.609 | 1.468 | 1.514 |

| Tank | TRAF family member-associated Nf-kappa B activator | 0.718 | 2.204 | 0.351 |

| Tlr6 | toll-like receptor 6 | 0.480 | 1.141 | 3.559 |

| ISGs | ||||

| Ifnb1 | interferon beta 1, fibroblast | 1.388 | 0.644 | 1.003 |

| Irf7 | interferon regulatory factor 7 | 1.500 | 0.677 | 0.406 |

| Ifrd1 | interferon-related developmental regulator 1 | 2.248 | 0.337 | 1.011 |

| Ifnar1 | interferon (alpha and beta) receptor 1 | 1.884 | 0.855 | 0.356 |

| Igtp | interferon gamma induced GTPase | 1.863 | 0.671 | 0.524 |

| Irf1 | interferon regulatory factor 1 | 0.549 | 2.715 | 0.671 |

| Irf3 | interferon regulatory factor 3 | 0.845 | 1.759 | 0.479 |

| Irf6 | interferon regulatory factor 6 | 0.601 | 1.816 | 1.282 |

| Ifngr1 | interferon gamma receptor 1 | 0.582 | 4.515 | 0.308 |

| Ifrg15 | interferon alpha responsive gene | 0.591 | 1.913 | 1.168 |

To further investigate whether similar mechanisms were involved in failure of tumor rejection in tolerance model and evasion model, we characterized potential differences between the two models of immune resistance; we compared statistical differences between the tolerogenic and the evasion model comparing the two non-regressing groups by unpaired Student t test using as a significance threshold a p-value < 0.001. This analysis was performed on pre-selected genes that had been filtered for an at least 80% presence of data in the whole data set and a minimal fold increase of 3 in at least one experiment (Fig. 3). This analysis identified 1,369 genes differentially expressed by the two groups (multivariate permutation test p-value = 0) of which 462 were up-regulated in the tolerogenic model and 907 were up-regulated in the tumor evasion model (Fig. 3A). Several of these genes where specifically expressed by either group although the expression of a few of them was shared by the regressing MCC tumors. Annotations and functional analysis based on Genontology data base (GEO) demonstrated that the predominant functional classes of genes transcriptionally active in one of the other type of non-responding MMC tumors were not associated with classical activation of T cell effector functions but rather were associated with more general metabolic processes (Fig. 3B and C). However, detailed analysis of transcripts associated with immunological function (Table 3) defined dramatic differences between the two mechanisms of immune resistance.

Figure 3. Gene expression profiling and gene oncology pathway analyses in tolerance and evasion models.

(A) Supervised cluster analysis (Student t test, p< 0.001 and fold change >3) comparing evasion (blue bar) and tolerogenic group (turquoise bar). 1326 differentially expressed genes have been visualized including also tumor regression samples (pink bar). Gene ontology pathway analysis projecting either up-regulated pathways in evasion group (B, 854 genes) or tolerogenic tumor models (C, 475 genes).

Discussion

FVB mice reject primary MMC by T cell-mediated neu-specific immune responses. However, a fraction of animals develop tumor relapse after a long latency. On the other hand their transgenic counterparts, FVBN202, fail to mount effective neu-specific immune responses and develop tumors (19). Although FVBN202 mice appear to elicit weak immune responses against the neu protein within a certain window of time (22), the neu expressing MMC tumors are still well tolerated and animals develop spontaneous mammary tumors. Despite the observation that T cells derived from FVB mice were capable of recognizing MMC and inducing apoptosis in these tumors in vitro, adoptive transfer of such effector T cells into FVBN202 mice failed to protect these animals against challenge with MMC.

It has been suggested that T cells play a significant role in determining the natural history of colon (14–16) and ovarian (17) cancer in humans. Transcriptional signatures have been identified that suggest not only T cell localization but also activation through the expression of IFN-γ, ISGs and cytotoxic effector molecules such as granzyme-B (10). We have recently shown that rejection of basal cell cancer induced by the activation of Toll-like receptor agonists also is mediated, at least in part, by localization and activation of CD8 expressing T cells with increased expression of cytotoxic molecules (34). Yet, a comprehensive experimental overview of the biological process associated with tumor rejection in its active phase has not been reported. Thus, our first class comparison searched for differences between the four tumor samples undergoing rejection and the rest of the MMC tumors whether belonging to the tolerogenic or the evasion process. Unlike non-regressing tumors (tolerance and evasion models), regressing tumors (rejection model) showed up-regulation of immune activation genes, suggesting that failure in tumor rejection is due to immune evasion or severely hampered immune responses in the tumor microenvironment. A particularly interesting observation was the relative low expression of ISGs, with the exception of IRF-2bp1. While the transcriptional patterns differentiating regressing from non-regressing tumors were striking and in many ways representative of previous observations in humans by our and others groups (35), differences among MMC tumors non-regressing in FVBN202 mice and those relapsing after regression in FVB mice were subtle. We have previously proposed that lack of regression of human tumors is primarily associated with indolent immune responses rather than dramatic changes in the tumor microenvironment enacted to counterbalance a powerful effector immune response (13, 31, 35). The MMC tolerance model allowed investigating this hypothesis at least in this restricted case. Spontaneous mammary tumors or transplanted MMC tumors in FVBN202 mice displayed immune suppressive properties that were identified by transcriptional profiling through the activation of genes associated with regulatory function. This would occur only in case an indolent adaptive immune response occurred in these transgenic mice and was hampered at the tumor site by a mechanism of peripheral suppression. If however, central tolerance was the reason for the lack of rejection, minimal changes should be observed in tolerogenic model similar to those detectable in the tumor evasion model where MMC tumors lost expression of HER-2/neu and become irrelevant targets for HER-2/neu-specific T cell responses. The presence of regulatory mechanism within the microenvironment of MCC-bearing FVBN202 mice was associated with increased IL-10 as well as increased expression of SOCS-1 and SOCS-3. It has recently been shown that myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDCS) induce macrophages to secret IL-10 and suppress anti-tumor immune responses (36). Importantly, it was shown that high levels of MDCS in neu transgenic mice would suppress anti-tumor immune responses against tumors (37). Interleukin-10 is increasingly recognized to be strongly associated with regulatory T cell (38) and M2 type tumor-associated macrophage function (39) and its expression is mediated in the context of chronic inflammatory stimuli by the over-expression of IRF-1. SOCS-1 inhibits type I IFN response, CD40 expression in macrophages, and TLR signaling (40–42). Expression of SOCS-3 in DCs converts them into tolerogenic DCs and support Th-2 differentiation (43). Importantly, tumors that express SOCS-3 show IFN-γ resistance (44).

Unlike tolerance model, recurrence model revealed expression of Igtp, suggesting the involvement of IFN-γ in this model (Table 3). This observation is consistent with our previous findings on the role of IFN-γ in neu loss and tumor recurrence (19). MMC tumors evading immune recognition had undergone a process of complex immune editing that resulted not only in the loss of the HER-2/neu target antigen but also in the up-regulation of various Th2 type cytokines such as IL-4 and, IL-13 (45) and the corresponding transcription factor IRF-7 over-expression predominantly associated to a deviation from cellular Th-1 to Th-2 and humoral type immune responses (46). In addition, the microenvironment of recurrent tumors was characterized by the coordinate expression of STAT-4, IL12b, IL-23r and IL-17; this cascade has been associated with the development of Th17 type immune responses that play a dominant role in autoimmune inflammation (47, 48) and T-cell dependent cancer rejection (49, 50). Since both humoral and cellular immune responses are potentially involved in the rejection of HER-2/neu expressing tumors (51), this data suggests that a cognitive and active immune response is still attempting to eradicate MMC tumors which may still express subliminal levels of the target antigen. However, the overall balance between host and cancer cells favors, in the end, tumor cell growth because the expression of HER-2/neu, the primary target of both cellular and humoral responses, is critically reduced.

Altogether, these observations suggest that neu antigen loss and subsequent immunological evasion from cellular Th-1 to Th-2 and humoral type immune response is a major mechanism in evasion model while peripheral suppression such as sustained IL-10, SOCS1 and SOCS3 expression is a major player in tolerance model. This conclusion provides a satisfactory explanation for the lack of rejection of MMC tumors in FVBN202 mice receiving adoptively transferred HER-2/neu-specific T cells. In this case, effective T cell responses exclude central tolerance or peripheral ignorance as the only mechanism potentially hampering their effector function at the tumor site suggesting that other regulatory mechanisms such as peripheral suppression could be responsible for inactivation of donor effector T cells. High levels of MDSC in neu transgenic mice support this possibility, and the role and mechanisms of MDSC in suppression of adoptively transferred neu-specific T cells remain to be determined in FVBN202 mice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 CA104757 grant (MHM) and flow cytometry shared resources facility supported in part by the NIH grant P30CA16059. We thank Laura Graham for her assistance with performing AIT. We gratefully acknowledge the support of VCU Massey Cancer Centre and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH R01 CA104757 grant (MHM) and flow cytometry shared resources facility supported in part by the NIH grant P30CA16059.

References

- 1.Marincola FM, Rivoltini L, Salgaller ML, Player M, Rosenberg SA. Differential anti-MART-1/MelanA CTL activity in peripheral blood of HLA-A2 melanoma patients in comparison to healthy donors: evidence for in vivo priming by tumor cells. J Immunother. 1996;19:266–77. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Souza S, Rimoldi D, Lienard D, Lejeune F, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Circulating Melan-A/Mart-1 specific cytolytic T lymphocyte precursors in HLA-A2+ melanoma patients have a memory phenotype. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:699–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19981209)78:6<699::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee K-H, Wang E, Nielsen M-B, et al. Increased vaccine-specific T cell frequency after peptide-based vaccination correlates with increased susceptibility to in vitro stimulation but does not lead to tumor regression. J Immunol. 1999;163:6292–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marincola FM. A balanced review of the status of T cell-based therapy against cancer. J Transl Med. 2005;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panelli MC, Riker A, Kammula US, et al. Expansion of Tumor-T cell pairs from Fine Needle Aspirates of Melanoma Metastases. J Immunol. 2000;164:495–504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zippelius A, Batard P, Rubio-Godoy V, et al. Effector function of human tumor-specific CD8 T cells in melanoma lesions: a state of local functional tolerance. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2865–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, Sherry RM, Morton KE, et al. Tumor progression can occur despite the induction of very high levels of self/tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;175:6169–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Disis ML, Calenoff E, McLaughlin G, et al. Existent T-cell and antibody immunity to HER-2/neu protein in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PP, Yee C, Savage PA, et al. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:677–85. doi: 10.1038/9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monsurro’ V, Wang E, Yamano Y, et al. Quiescent phenotype of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells following immunization. Blood. 2004;104:1970–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagorsen D, Voigt S, Berg E, Stein H, Thiel E, Loddenkemper C. Tumor-infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells in human colorectal cancer: relation to local regulatory T cells, systemic T-cell response against tumor-associated antigens and survival. J Transl Med. 2007;5:62. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marincola FM, Jaffe EM, Hicklin DJ, Ferrone S. Escape of human solid tumors from T cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:181–273. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marincola FM, Wang E, Herlyn M, Seliger B, Ferrone S. Tumors as elusive targets of T cell-based active immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:335–42. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pages F, Berger A, Camus M, et al. Effector memory T cells, early metastasis, and survival in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galon J, Fridman WH, Pages F. The adaptive immunologic microenvironment in colorectal cancer: a novel perspective. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1883–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:203–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kmieciak M, Knutson KL, Dumur CI, Manjili MH. HER-2/neu antigen loss and relapse of mammary carcinoma are actively induced by T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:675–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manjili MH, Arnouk H, Knutson KL, et al. Emergence of immune escape variant of mammary tumors that has distinct proteomic profile and a reduced ability to induce “danger signals”. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:233–41. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guy CT, Webster MA, Schaller M, Parsons TJ, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10578–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeuchi N, Hiraoka S, Zhou XY, et al. Anti-HER-2/neu immune responses are induced before the development of clinical tumors but declined following tumorigenesis in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7588–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kmieciak M, Morales JK, Morales J, Grimes M, Manjili MH. Danger signal and nonself entity of tumor antigen are both required for eliciting effective immune responses against HER-2/neu positive mammary carcinoma: implications for vaccine design. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0475-8. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knutson KL, Almand B, Dang Y, Disis ML. Neu antigen-negative variants can be generated after neu-specific antibody therapy in neu transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1146–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang E, Miller L, Ohnmacht GA, Liu E, Marincola FM. High fidelity mRNA amplification for gene profiling using cDNA microarrays. Nature Biotech. 2000;17:457–9. doi: 10.1038/74546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang E. RNA amplification for successful gene profiling analysis. J Transl Med. 2005;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin P, Zhao Y, Ngalame Y, et al. Selection and validation of endogenous reference genes using a high throughput approach. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubinfeld B, Robbins P, el Gamil M, Albert I, Porfiri E, Polakis P. Stabilization of beta-catenin by genetic defects in melanoma cell lines. Science. 1997;275:1790–2. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14863–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross DT, Scherf U, Eisen MB, et al. Systematic variation in gene expression patterns in human cancer cell lines. Nature Genetics. 2000;24:227–35. doi: 10.1038/73432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang E, Miller LD, Ohnmacht GA, et al. Prospective molecular profiling of subcutaneous melanoma metastases suggests classifiers of immune responsiveness. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3581–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basil CF, Zhao Y, Zavaglia K, et al. Common cancer biomarkers. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2953–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaech SM, Hemby S, Kersh E, Ahmed R. Molecular and functional profiling of memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Cell. 2002;111:837–51. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panelli MC, Stashower M, Slade HB, et al. Sequential gene profiling of basal cell carcinomas treated with Imiquimod in a placebo-controlled study defines the requirements for tissue rejection. Genome Biol. 2006;8:R8. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, Marincola FM. Tumor immunity: effector response to tumor and the influence of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2007 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60241-X. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha P, Clements VK, Bunt SK, Albelda SM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and macrophages subverts tumor immunity toward a type 2 response. J Immunol. 2007;179:977–83. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melani C, Chiodoni C, Forni G, Colombo MP. Myeloid cell expansion elicited by the progression of spontaneous mammary carcinomas in c-erbB-2 transgenic BALB/c mice suppresses immune reactivity. Blood. 2003;102:2138–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu K, Bi Y, Sun K, Wang C. IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells and allergy. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:269–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional programme expressed by tumor-associated macrophages: defective NF-{kappa}B and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation. Blood. 2006;107:2112–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fenner JE, Starr R, Cornish AL, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 regulates the immune response to infection by a unique inhibition of type I interferon activity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:33–9. doi: 10.1038/ni1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mansell A, Smith R, Doyle SL, et al. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 negatively regulates Toll-like receptor signaling by mediating Mal degradation. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:148–55. doi: 10.1038/ni1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin H, Wilson CA, Lee SJ, Benveniste EN. IFN-beta-induced SOCS-1 negatively regulates CD40 gene expression in macrophages and microglia. FASEB J. 2006;20:985–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5493fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Chu N, Rostami A, Zhang GX. Dendritic cells transduced with SOCS-3 exhibit a tolerogenic/DC2 phenotype that directs type 2 Th cell differentiation in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:1679–88. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fojtova M, Boudny V, Kovarik A, et al. Development of IFN-gamma resistance is associated with attenuation of SOCS genes induction and constitutive expression of SOCS 3 in melanoma cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:231–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroemer G, Hirsch F, Gonzalez-Garcia A, Martinez C. Differential involvement of Th1 and Th2 cytokines in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity. 1996;24:25–33. doi: 10.3109/08916939608995354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaki S, Amara RR, Yeow WS, Pitha PM, Robinson HL. Regulation of DNA-raised immune responses by cotransfected interferon regulatory factors. J Virol. 2002;76:6652–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6652-6659.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hunter CA. New IL-12-family members: IL-23 and IL-27, cytokines with divergent functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:521–31. doi: 10.1038/nri1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Afzali B, Lombardi G, Lechler RI, Lord GM. The role of T helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T cells (Treg) in human organ transplantation and autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:32–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hao JS, Shan BE. Immune enhancement and anti-tumour activity of IL-23. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1426–31. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0171-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shan BE, Hao JS, Li QX, Tagawa M. Antitumor activity and immune enhancement of murine interleukin-23 expressed in murine colon carcinoma cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fulton A, Miller F, Weise A, Wei WZ. Prospects of controlling breast cancer metastasis by immune intervention. Breast Dis. 2006;26:115–27. doi: 10.3233/bd-2007-26110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.