Abstract

Time-resolved visible pump/mid-infrared (mid-IR) probe spectroscopy in the region between 1600 and 1800 cm−1 was used to investigate electron transfer, radical pair relaxation, and protein relaxation at room temperature in the Rhodobacter sphaeroides reaction center (RC). Wild-type RCs both with and without the quinone electron acceptor QA, were excited at 600 nm (nonselective excitation), 800 nm (direct excitation of the monomeric bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) cofactors), and 860 nm (direct excitation of the dimer of primary donor (P) BChls (PL/PM)). The region between 1600 and 1800 cm−1 encompasses absorption changes associated with carbonyl (C=O) stretch vibrational modes of the cofactors and protein. After photoexcitation of the RC the primary electron donor P excited singlet state (P*) decayed on a timescale of 3.7 ps to the state  (where BL is the accessory BChl electron acceptor). This is the first report of the mid-IR absorption spectrum of

(where BL is the accessory BChl electron acceptor). This is the first report of the mid-IR absorption spectrum of  the difference spectrum indicates that the 9-keto C=O stretch of BL is located around 1670–1680 cm−1. After subsequent electron transfer to the bacteriopheophytin HL in ∼1 ps, the state

the difference spectrum indicates that the 9-keto C=O stretch of BL is located around 1670–1680 cm−1. After subsequent electron transfer to the bacteriopheophytin HL in ∼1 ps, the state  was formed. A sequential analysis and simultaneous target analysis of the data showed a relaxation of the

was formed. A sequential analysis and simultaneous target analysis of the data showed a relaxation of the  radical pair on the ∼20 ps timescale, accompanied by a change in the relative ratio of the

radical pair on the ∼20 ps timescale, accompanied by a change in the relative ratio of the  and

and  bands and by a minor change in the band amplitude at 1640 cm−1 that may be tentatively ascribed to the response of an amide C=O to the radical pair formation. We conclude that the drop in free energy associated with the relaxation of

bands and by a minor change in the band amplitude at 1640 cm−1 that may be tentatively ascribed to the response of an amide C=O to the radical pair formation. We conclude that the drop in free energy associated with the relaxation of  is due to an increased localization of the electron hole on the PL half of the dimer and a further consequence is a reduction in the electrical field causing the Stark shift of one or more amide C=O oscillators.

is due to an increased localization of the electron hole on the PL half of the dimer and a further consequence is a reduction in the electrical field causing the Stark shift of one or more amide C=O oscillators.

INTRODUCTION

The reaction center (RC) is a transmembrane pigment-protein complex responsible for light-driven charge separation in photosynthetic bacteria. The RC from the purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter (Rb.) sphaeroides was one of the first membrane proteins to be structurally characterized to atomic resolution by x-ray crystallography (1–3). An axis of pseudo-twofold symmetry relates the L and M subunits that, along with a third H subunit, form the basic core structure. The cofactors comprise two molecules of bacteriochlorophyll a (BChl, denoted PL and PM) that form the dimeric primary electron donor (P), two monomeric BChls (BL and BM), two bacteriopheophytins (BPhe, denoted HL and HM), two quinones (QA and QB), one nonheme iron (Fe), and one carotenoid. The BChl, BPhe, and quinone cofactors are arranged in two approximately symmetrical branches, termed L and M after the protein subunits.

The purple bacterial RC has been extensively investigated using ultrafast spectroscopic techniques, and it has been established that excitation of the P BChls results in the stepwise transfer of an electron along the L-branch of cofactors with an ∼100% efficiency. Electron transfer from P to the L-branch BPhe (HL) occurs in ∼4 ps at room temperature, whereas subsequent electron transfer to the ubiquinone QA occurs in ∼220 ps (4–7). The cation formed is shared between the PL and PM BChls that make up the P dimer. The role of the accessory BL molecule (located between the P and HL) in the electron transfer process, and in particular whether it acts as a real or a virtual intermediate, has been a matter of considerable debate. Much of this debate was caused by the difficulty in observing spectral changes related to the state  particularly in early studies (8,9). However, it is now generally accepted that the first step of electron transfer involves reduction of BL, and formation of the

particularly in early studies (8,9). However, it is now generally accepted that the first step of electron transfer involves reduction of BL, and formation of the  radical pair, with the rate of subsequent electron transfer from

radical pair, with the rate of subsequent electron transfer from  to HL being three to four times faster than the initial electron transfer from P* to BL (7,10,11). In the classical picture, excitation of the BPhes or accessory BChls of the RC results in ultrafast energy transfer to P, forming a P* state that initiates L-branch electron transfer.

to HL being three to four times faster than the initial electron transfer from P* to BL (7,10,11). In the classical picture, excitation of the BPhes or accessory BChls of the RC results in ultrafast energy transfer to P, forming a P* state that initiates L-branch electron transfer.

In this stepwise model of charge separation the free energy of the  radical pair is described as being just below that of P*. It has been concluded that the free energy of the

radical pair is described as being just below that of P*. It has been concluded that the free energy of the  state lies ∼450 cm−1 below that of the initially excited primary donor P*, with a further (180 cm−1) drop in free energy on formation of

state lies ∼450 cm−1 below that of the initially excited primary donor P*, with a further (180 cm−1) drop in free energy on formation of  (12).

(12).

A number of experiments have challenged the classical picture in which excitation of the accessory BChl or BPhe cofactors leads uniquely to ultrafast energy transfer to P, forming P*. It was shown that after excitation of the monomeric BChls at 800 nm, direct formation of the radical pairs  and

and  occurs without the involvement of P*, this very fast charge separation competing with energy transfer from these pigments to P. The work of van Brederode et al. (13–15) showed that this P*-independent charge separation occurs mainly after excitation of the blue side of the 800 nm absorbance band of the Rb. sphaeroides RC, and therefore involves the accessory BChl on the active L-branch (excitation of the BPhe on the L-branch also leads to direct charge separation).

occurs without the involvement of P*, this very fast charge separation competing with energy transfer from these pigments to P. The work of van Brederode et al. (13–15) showed that this P*-independent charge separation occurs mainly after excitation of the blue side of the 800 nm absorbance band of the Rb. sphaeroides RC, and therefore involves the accessory BChl on the active L-branch (excitation of the BPhe on the L-branch also leads to direct charge separation).

The picture of light-driven electron transfer in the RC is further complicated by relaxation events that occur on the timescale of the electron transfer process. For example, the multi-exponential decay of the recombination fluorescence from P* observed in RCs where electron transfer to QA is blocked has been interpreted in terms of relaxation of the originally formed radical pair states (9,16,17). In this model the multi-exponential decay of the fluorescence is thought to originate from a decrease in the free energy of the  radical pair with time. Similarly, from a target analysis of data obtained in pump-probe measurements the radical pair

radical pair with time. Similarly, from a target analysis of data obtained in pump-probe measurements the radical pair  was observed to relax with a time constant in the tens of ps range (18). Such relaxations result from slow nuclear motions in the protein-cofactor system, and the role(s) played by the protein component of the RC during the initial energy and electron transfer events remains poorly understood.

was observed to relax with a time constant in the tens of ps range (18). Such relaxations result from slow nuclear motions in the protein-cofactor system, and the role(s) played by the protein component of the RC during the initial energy and electron transfer events remains poorly understood.

The purpose of the work described in this study was to examine photochemical charge separation in the Rb. sphaeroides RC through the application of femtosecond timescale infrared (IR) spectroscopy. In principle, identification of the rate of P+ formation and acceptor reduction should be straightforward when analyzing the large manifold of vibrational bands afforded by mid-IR spectroscopy (although at the cost of much lower extinction coefficients), because the spectra of the BChl and BPhe molecules in their neutral, excited, or radical state display very specific signatures in the mid-IR. Time-resolved mid-IR spectroscopy also opens up the unique possibility of investigating the protein response that follows electron transfer, and therefore the relaxation processes that occur in the vicinity of the cofactors on the timescale of electron transfer. For the bacterial RC, several studies of the initial electron transfer dynamics and protein response to this process have been reported (19–25). Hamm et al. (19) carried out measurements on Rb. sphaeroides RCs in the mid-IR region between 1000 and 1800 cm−1, with a time resolution of 400 fs. Two components were found in this work, one increasing with a time constant of 3.8 ps ascribed to the formation of  and one decaying with a time constant of 240 ps ascribed to electron transfer to the final

and one decaying with a time constant of 240 ps ascribed to electron transfer to the final  state. However, a fast kinetic component attributable to electron transfer from

state. However, a fast kinetic component attributable to electron transfer from  to

to  was not found in this study. A strong 200 fs component observed in a second IR experiment by Hamm et al. (20) was assigned to an ultrafast internal charge separation within the primary donor BChl dimer (i.e., formation of P+P−). In ps transient absorption studies of Rb. sphaeroides RCs in the range 1550–1800 cm−1 by Hochstrasser et al. (21), transitions of amide I were observed at a number of frequencies on a timescale shorter than 50 ps that suggested coupling of the electron transfer process with a specific part of protein backbone. Later in mid-IR experiments with 400 fs time-resolution (22) features related to the states P, P*, and P+ were identified in the difference spectra. The 9-keto modes of the P ground state were found at 1682 cm−1, and those of

was not found in this study. A strong 200 fs component observed in a second IR experiment by Hamm et al. (20) was assigned to an ultrafast internal charge separation within the primary donor BChl dimer (i.e., formation of P+P−). In ps transient absorption studies of Rb. sphaeroides RCs in the range 1550–1800 cm−1 by Hochstrasser et al. (21), transitions of amide I were observed at a number of frequencies on a timescale shorter than 50 ps that suggested coupling of the electron transfer process with a specific part of protein backbone. Later in mid-IR experiments with 400 fs time-resolution (22) features related to the states P, P*, and P+ were identified in the difference spectra. The 9-keto modes of the P ground state were found at 1682 cm−1, and those of  and

and  at 1714 cm−1 and 1702 cm−1, respectively. A fast transition at 1665 cm−1 was further assigned to either P* or

at 1714 cm−1 and 1702 cm−1, respectively. A fast transition at 1665 cm−1 was further assigned to either P* or  whereas a signal appearing concomitant with charge separation at 1665 cm−1 was proposed to be due to small frequency shifts and intensity changes of a large number of amide oscillators, in response to the charge separation. In Walker et al. (23) the electronic transitions of P* and P+ were measured in the 1700–2000 cm−1 region, and the P* transition was found to be present 300 fs after light absorption and decay to the P+ state in 3.4 ps. A further exploration of the near-IR region (24,25) led to the observation of four transitions assigned to the charge transfer states

whereas a signal appearing concomitant with charge separation at 1665 cm−1 was proposed to be due to small frequency shifts and intensity changes of a large number of amide oscillators, in response to the charge separation. In Walker et al. (23) the electronic transitions of P* and P+ were measured in the 1700–2000 cm−1 region, and the P* transition was found to be present 300 fs after light absorption and decay to the P+ state in 3.4 ps. A further exploration of the near-IR region (24,25) led to the observation of four transitions assigned to the charge transfer states  or

or  Two bands were observed in the P* state, at 5300 cm−1 and 2710 cm−1, and two bands in the

Two bands were observed in the P* state, at 5300 cm−1 and 2710 cm−1, and two bands in the  spectrum, at 8000 cm−1, and a hole transfer band at 2600 cm−1.

spectrum, at 8000 cm−1, and a hole transfer band at 2600 cm−1.

Recently, near-IR pump/UV probe spectroscopy was used to examine the initial electron transfer in wild-type RCs and 14 mutant complexes containing engineered tryptophan residues (26). Although the kinetics of charge separation were very different for the studied mutants, the protein relaxation kinetics measured as the decay of an initial absorption change of tryptophan after P* formation showed the same pattern for all the RCs. The conclusion drawn from these findings was that the initial charge separation is limited by the protein dynamics, which were initiated by the absorption of light rather than by charge separation.

In this work, we describe the mid-IR response of Rb. sphaeroides RCs after nonselective excitation in the visible region at 600 nm, and selective excitation in the near-IR at 805 nm and 860 nm. RCs both with and without the QA quinone were compared to examine the fate of the  state. We conclude that characteristic absorption features of all the states involved in the primary events in the RC can be identified, including the poorly-characterized state

state. We conclude that characteristic absorption features of all the states involved in the primary events in the RC can be identified, including the poorly-characterized state  It is concluded that BL is strongly H-bonded, most likely to water molecule. A detailed kinetic scheme devised to fit the data is in good agreement with earlier reaction models proposed on the basis of visible pump-probe and fluorescence data. We identify signals that rise with the kinetics of charge separation at 1666/1656 cm−1 reflecting the protein response to charge separation. Finally, we find that a relaxation of the equilibrium between P* and the

It is concluded that BL is strongly H-bonded, most likely to water molecule. A detailed kinetic scheme devised to fit the data is in good agreement with earlier reaction models proposed on the basis of visible pump-probe and fluorescence data. We identify signals that rise with the kinetics of charge separation at 1666/1656 cm−1 reflecting the protein response to charge separation. Finally, we find that a relaxation of the equilibrium between P* and the  radical pair on the ∼20 ps timescale is accompanied by a change in the relative ratio of the

radical pair on the ∼20 ps timescale is accompanied by a change in the relative ratio of the  and

and  bands. We conclude that the drop in free energy associated with the relaxation of

bands. We conclude that the drop in free energy associated with the relaxation of  is due to an increased localization of the electron hole on the PL half of the dimer.

is due to an increased localization of the electron hole on the PL half of the dimer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All experiments were carried out with a femtosecond visible-pump/mid-IR-probe laser setup that has been described previously (27,28). The femtosecond pulse generator included an integrated Ti:sapphire oscillator and regenerative amplifier laser system (Hurricane, Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA), and produced 800 nm, 85 fs pulses at a repetition rate of 1 kHz, and an energy of 0.6 mJ. Part of the light was passed through a noncollinear optical parametric amplifier, where white light and the second harmonic were generated. The 860 nm excitation light was produced using an 860-nm interference filter placed in the path of the white light seed. The pump pulses were directed through an optical delay line and a chopper operating at 500 Hz. The polarization of the excitation pulses was set to the magic angle (54.7°) with respect to the IR probe pulse using a polarization rotator placed behind the delay line. The second part of the 800 nm light (energy 360 μJ) was used to pump an optical parametric generator and amplifier with a difference frequency generator (TOPAS, Light Conversion, Vilnius, Lithuania) to produce the mid-IR probe pulses. The visible pump and mid-IR probe pulses were attenuated and focused onto the sample with 20 cm and 6 cm lenses, respectively, the size of the pump beam being ∼125 μm. After passing the sample the mid-IR probe pulses were dispersed using a spectrograph and imaged onto a 32-element HgCdT array detector operating at 77 K that provided a spectral window of ∼100 cm−1 or 200 cm−1 with a corresponding spectral resolution of 3 cm−1 or 6 cm−1, respectively. Signals from the detector array (Infrared Systems Development, Winter Park, Florida) were amplified and fed into 32 home-built integrate-and-holds, which were read out on every shot with a National Instruments (Austin, Texas) acquisition card (PCI6031E). A phase-locked chopper operating at 500 Hz was used to ensure that the sample was excited on every other shot and so the change in transmission and hence optical density could be measured. An overlap of the pump and probe pulses was found in GaAs sample and the instrument response function (IRF) was of the order of ∼100 fs. The sample was moved in a home-built Lissajous scanner, to ensure the excitation of a fresh part of the sample at every shot. Rb. sphaeroides RCs were isolated according to standard procedures (29). The construction, spectroscopic analysis and x-ray crystal structure of the mutant AM260W have been described in detail (30–32). The QA ubiquinone was removed chemically from R26 RCs using a procedure described previously (33) as modified by Woodbury et al. (34). For the vis/mid-IR experiments RCs were suspended in a D2O buffer of 100 mM Tris (pH 7.6) and the optical density of the sample was adjusted to between 0.2 and 0.3 at 800 nm for a 20-μm path length. A closed cell consisting of two CaF2 windows separated by a 20-μm Teflon spacer was filled with ∼40 μl of the RC solution and placed in a housing that was purged with a flow of N2 to reduce the effect of water vapor on the mid-IR pulses. The RCs were excited with three different wavelengths: at 600 nm (nonselective excitation of all BChls, fwhm = 9 nm), 805 nm (excitation mainly of the accessory BChls, fwhm = 8 nm), and 860 nm (selective excitation of P, fwhm = 10 nm), with excitation power of 300 nJ for 600 nm and 805 nm excitation and 250 nJ for 860 nm excitation. For each excitation wavelength experiments were repeated twice using fresh samples, with spectra being recorded at 80 different time points. In a single experiment a spectral probe window of ∼200 cm−1 was covered, so four partly overlapping regions were measured between 1580 and 2300 cm−1. All data were subjected to global and target analysis (18,35).

RESULTS

Reaction centers with QA removed: nonselective excitation at 600 nm

R26 RCs in which the QA ubiquinone had been removed (see Materials and Methods) were nonselectively excited at 600 nm, corresponding to a largely unstructured absorbance band arising from the Qx transitions of all four BChl cofactors. The resulting absorption changes in the mid-IR were measured in the frequency window 1780–1600 cm−1, covering the area corresponding to stretching modes of the carbonyl (C=O) groups of the cofactors and protein. In the case of the BChl and BPhe cofactors three such C=O groups, referred to as the 2a-acetyl, 9-keto, and 10a-ester carbonyls, are expected to contribute to the spectrum.

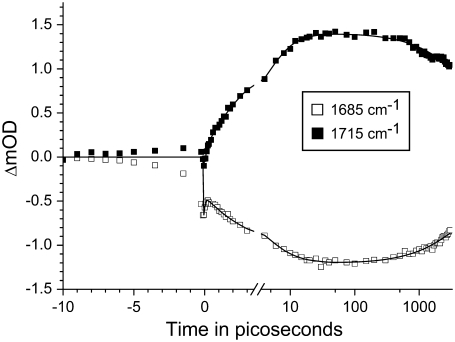

Fig. 1 shows two selected time traces detected at 1685 cm−1 (open squares) and 1715 cm−1 (solid squares). The fit through the data is the result of a global analysis of the whole data set using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes. The resulting evolution associated difference spectra (EADS; Fig. 2) reflect the spectral evolution of the system in time, but do not necessarily represent ‘pure’ states, as discussed in detail elsewhere (18,35). The global analysis yielded five kinetic components with lifetimes of ∼100 fs, 3.8 ps, 16 ps, 4 ns, and a nondecaying component (Table 1). The observation of the ‘pure’ ultrafast process of energy transfer is perturbed in fs mid-IR spectroscopy by a component that follows the IRF and describes a coherent interaction of the laser pulses with the sample. For this reason the resolved ∼100 fs components were not shown in any of EADS and SADS presented in this work. Also the negative signal before time zero visible in the 1685 cm−1 and 1715 cm−1 traces shown in Fig. 1 originated from perturbed free induction decay (36,37), and was not included in the fit. Because no reference probe pulse was used, the noise in the measured spectra (not shown) consisted mainly of so-called baseline noise, i.e., a flat, structureless offset in the spectra that was easily recognized by a singular vector decomposition of the residual matrix. For target analysis (and the time traces in Fig. 1), the outer product of the first two singular vector pairs of the residual matrix (being structureless in the time domain) was subtracted from the data, leading to reduction in the noise by a factor of 2.

FIGURE 1.

Two representative time traces measured using Rb. sphaeroides R26 RCs lacking QA, excited at 600 nm, and probed at 1685 cm−1 and 1715 cm−1. The solid lines through the data points are the result of a global fit using a sequential model with time constants of: τ1 = 120 fs, τ2 = 3.8 ps, τ3 = 16 ps, τ4 = 4 ns, and τ5= infinite. IRF width = 150 fs FWHM. The timescale is linear up to 3 ps and logarithmic thereafter.

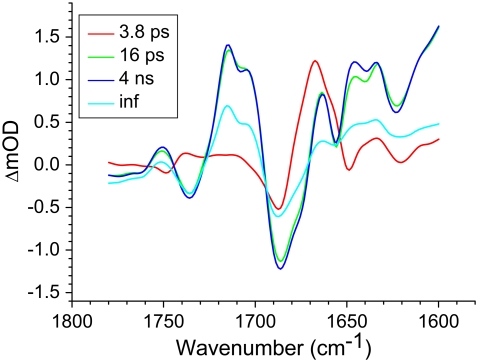

FIGURE 2.

EADS of R26 RCs lacking QA, excited at 600 nm, resulting from a global analysis using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes. The measurements were carried out over a 1780–1600 cm−1 window with a spectral resolution of 6 cm−1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the lifetimes resulting from global analysis of the data obtained in individual experiments

| Sample | Excitation wavelength (nm) | IR region/resolution (cm−1) | Lifetimes from global analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| R26 - QA removed | 600 | 1780–1600/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.8 ps, 16 ps, 4.0 ns, infinite |

| R26 - QA removed | 805 | 1775–1590/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.0 ps, 12 ps, 4.0 ns, infinite |

| R26 - QA removed | 860 | 1775–1590/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.0 ps, 17 ps, 4.7 ns, infinite |

| R26 - QA removed | 805 | 1783–1693/3 | 2.6 ps, 7.2 ps, 1.7 ns, infinite |

| AM260W | 860 | 1775–1590/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.0 ps, 17 ps, 430 ps, infinite |

| R26 - QA removed | 600 | 1908–1736/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.8 ps, infinite |

| 2160–1930/6 | |||

| 2254–2060/6 | |||

| 2280–2111/3 | |||

| R26 - QA intact | 860 | 1780–1590/6 | ∼100 fs, 3.6 ps, 280 ps, infinite |

| R26 - QA intact | 600 | 1775–1590/6 | ∼100 fs, 4.4 ps, 222 ps, infinite |

In the EADS shown in Fig. 2 negative bands refer to ground state vibrational modes and positive bands to the shifted vibrational modes in the excited or charge separated state. Ultrafast Qx to Qy relaxation of the excited states of P and energy transfer from BL* and BM* led to the formation of the state assigned to the excited state of the primary electron donor P* (Fig. 2, red spectrum), which decayed in 3.8 ps into the state represented by the green spectrum. The 16 ps (green) and 4 ns (blue) spectra were very similar, but nevertheless some dynamics could be seen. In seeking to assign these spectra it should be noted that measurements of delayed fluorescence in isolated RCs in which electron transfer to QA was blocked (9) or QA was replaced (34), and transient absorption experiments on isolated RCs containing QA (38) and on membrane-bound RCs (18), have shown a multi-exponential decay of P* plus an increase in the amount of  on a timescale of ∼20 ps. These observations have led to the conclusion that the equilibrium between P* and the

on a timescale of ∼20 ps. These observations have led to the conclusion that the equilibrium between P* and the  radical pair shifts toward the latter due to a drop in its free energy. A kinetic model taking these observations (9,34,38) into account was developed by van Stokkum et al. (18). Guided by this, in this study the 16 ps spectrum was assigned to the initially-formed

radical pair shifts toward the latter due to a drop in its free energy. A kinetic model taking these observations (9,34,38) into account was developed by van Stokkum et al. (18). Guided by this, in this study the 16 ps spectrum was assigned to the initially-formed  state (denoted (

state (denoted ( )1), whereas the 4 ns spectrum was assigned to a relaxed form of this state (denoted

)1), whereas the 4 ns spectrum was assigned to a relaxed form of this state (denoted  These spectra are clearly rich in features and display a number of negative bands, several of which can be assigned with reference to steady-state FTIR difference spectra. The negative band centered at 1687 cm−1, which is more intense in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra than in the 3.8 ps spectrum, is assigned to the 9-keto C=O modes of PL and PM in the ground state. In FTIR experiments, where the state

These spectra are clearly rich in features and display a number of negative bands, several of which can be assigned with reference to steady-state FTIR difference spectra. The negative band centered at 1687 cm−1, which is more intense in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra than in the 3.8 ps spectrum, is assigned to the 9-keto C=O modes of PL and PM in the ground state. In FTIR experiments, where the state  was studied on a slow (ms) timescale, two bands corresponding to the 9-keto mode of P in the ground state were found, at 1692 cm−1 for PL and 1683 cm−1 for PM (39–41). The two positive bands at 1715 cm−1 and 1705 cm−1 are ascribed to the 9-keto modes of PL and PM, respectively, in the cation state P+; for convenience the cation state of these BChls is henceforth referred to as

was studied on a slow (ms) timescale, two bands corresponding to the 9-keto mode of P in the ground state were found, at 1692 cm−1 for PL and 1683 cm−1 for PM (39–41). The two positive bands at 1715 cm−1 and 1705 cm−1 are ascribed to the 9-keto modes of PL and PM, respectively, in the cation state P+; for convenience the cation state of these BChls is henceforth referred to as  and

and  although it should be noted that the single positive charge is shared between the two BChls of the dimer. These attributions are summarized in Table 2.

although it should be noted that the single positive charge is shared between the two BChls of the dimer. These attributions are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Assignments of positive and negative bands observed in time-resolved IR difference spectra and light-minus-dark FTIR difference spectra

| Bands | Assignments |

|---|---|

EADS without QA EADS without QA

|

|

| P/P+ modes | |

| 1736(−)/1751(+) | 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and  respectively respectively |

| 1715(+), 1705 (+) | 9-keto modes of  and and  respectively respectively |

| 1687(−) | 9-keto modes of PL and PM |

| 1624(−)/1635(+) | 2a-acetyl modes of

|

| 1642(−)/1647(+) | 2a-acetyl modes of

|

and protein modes and protein modes |

|

| 1747(−), 1732(−) | Free and H-bonded (to Trp L100) 10a-ester C=O of HL |

| 1675(−)/1591(+) | 9-keto C=O of HL hydrogen bonded to Glu L104 |

| 1656(−)/1663(+) | Upshift of an amide I C=O |

| 1656(−)/1646(+) | Conformational changes in the protein backbone due to HL transition from the neutral to the anion state and/or further  relaxation relaxation |

EADS without QA (3 cm−1 resolution) EADS without QA (3 cm−1 resolution) |

|

| 1739(−)/1751(+) | 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and  respectively respectively |

| 1746(−), 1733(−) | Free and H-bonded (to Trp L100)10a-ester C=O HL |

EADS with QA EADS with QA

|

|

| 1656(−)/1646(+) | Conformational changes in the protein backbone due to HL transition from the neutral to the anion state and/or further  relaxation relaxation |

EADS EADS |

|

| P/P+ modes | |

| 1739(−)/1750(+) | 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and  respectively respectively |

| 1715(+), 1705(+) | 9-keto modes of  and and  respectively respectively |

| 1687(−) | 9-keto modes of PL and PM |

and protein modes and protein modes |

|

| 1728(+) | Transition of 10a-ester C=O of HL in electric field of

|

| 1666(−)/1656(+) | Protein amide I transition on

|

| 1650(−)/1640(+) | Protein backbone C=O H-bonded to QA transition on

|

| 1630(−) | QA mode |

| 1600(−) | QA mode |

SADS SADS |

|

| 1687(−) | 9-keto C=O of PL and PM |

| 1739(−)/1750(+) | 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and  respectively respectively |

| 1715(+), 1705(+) | 9-keto modes of  and and  respectively respectively |

| 1650(−)/1640(+) | Response of protein C=O group |

| 1680–1670(−) | The ground state 9-keto C=O of BL |

| 1657(+) | 9-keto C=O of  - strong H-bond with protein - strong H-bond with protein |

Note that the discussed  and

and  spectra are EADS, resulting from the global analysis, whereas only the

spectra are EADS, resulting from the global analysis, whereas only the  spectrum is SADS as resolved in the target analysis.

spectrum is SADS as resolved in the target analysis.

Whereas the C=O modes of BChl and BPhe pigments upshift in the cation state, they downshift in both the excited (42) and anion states (43). The negative shoulder at 1675 cm−1 in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra in Fig. 2 can be ascribed to the 9-keto C=O of HL in the neutral state, which is hydrogen bonded to Glu L104 (44). In FTIR experiments this mode has been reported to undergo a very strong downshift to 1591 cm−1 upon charge separation (43), and evidence for this can be seen in the strongly positive signal appearing at the edge of the spectral window around 1600 cm−1 in the spectra of the 16 ps (Fig. 2, green) and 4 ns (Fig. 2, blue) components.

The C=O modes of the protein are expected to absorb in the range 1665–1620 cm−1 and partly overlap with signals due to BChl a 9-keto and 2a-acetyl C=O modes. The negative band at 1656 cm−1 in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra in Fig. 2 can be ascribed to an upshift of one or more amide C=O groups to 1663 cm−1 in response to the formation of  (21,22,43,45,46). Note however, that a contradictory assignment of this negative band at 1656 cm−1 has been proposed (44). In this assignment the 1656 cm−1 mode downshifts to 1646 cm−1 due to conformational changes in the protein backbone in response to electron transfer to HL (39), and/or further relaxation of

(21,22,43,45,46). Note however, that a contradictory assignment of this negative band at 1656 cm−1 has been proposed (44). In this assignment the 1656 cm−1 mode downshifts to 1646 cm−1 due to conformational changes in the protein backbone in response to electron transfer to HL (39), and/or further relaxation of  (44). Due to the low extinction coefficient of the BChl a 2a-acetyl modes and the presence of partially overlapping protein C=O modes an unequivocal assignment of the bands observed in the region between 1620 and 1650 cm−1 was not possible. The negative bands at 1642 and 1624 cm−1 in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra in Fig. 2 are probably attributable to the 2a-acetyl modes of PM and PL, respectively (39–41,45,47–49) and in the cation state these modes are expected to shift to higher frequency. The positive band at 1635 cm−1 could be due to the 2a-acetyl C=O of

(44). Due to the low extinction coefficient of the BChl a 2a-acetyl modes and the presence of partially overlapping protein C=O modes an unequivocal assignment of the bands observed in the region between 1620 and 1650 cm−1 was not possible. The negative bands at 1642 and 1624 cm−1 in the 16 ps and 4 ns spectra in Fig. 2 are probably attributable to the 2a-acetyl modes of PM and PL, respectively (39–41,45,47–49) and in the cation state these modes are expected to shift to higher frequency. The positive band at 1635 cm−1 could be due to the 2a-acetyl C=O of  upshifted from 1624 cm−1. However, it was not possible to assign the positive band at 1646 cm−1 to the upshifted 2-acetyl C=O of

upshifted from 1624 cm−1. However, it was not possible to assign the positive band at 1646 cm−1 to the upshifted 2-acetyl C=O of  because it might also be due to a perturbation of an amide I oscillator in the 1646/1656 cm−1 region (21,22,39) or further relaxation of the HL anion state (44).

because it might also be due to a perturbation of an amide I oscillator in the 1646/1656 cm−1 region (21,22,39) or further relaxation of the HL anion state (44).

It has been reported in the literature that in the 10a-ester region between 1760 and 1710 cm−1 a negative band at 1740 cm−1 and positive band 1750 cm−1 arise from the neutral and cation state, respectively of both PL and PM (39–41,45). This was indeed observed in the spectra of the 16 ps, 4 ns, and infinite components as a bleaching at ∼1736 cm−1 and an absorption increase at 1751 cm−1. It is possible that negative bands related to free and H-bonded modes of the 10a-ester group of HL at 1747 cm−1 and 1732 cm−1, respectively (44), could also contribute to this region of the EADS, but were not resolved due to the relatively low spectral resolution (6 cm−1). These attributions are returned to below, in the discussion of data recorded at a higher spectral resolution. Finally, the spectrum of the nondecaying component in Fig. 2 (cyan) shows a decrease in intensity for all bands. The evolution observed from the 4 ns spectrum (blue) to the nondecaying spectrum (cyan) mainly reflects the decay of the radical pair  in the absence of electron transfer to QA.

in the absence of electron transfer to QA.

Reaction centers with QA removed: selective excitation at 805 and 860 nm

R26 RCs lacking QA were also excited selectively at 805 nm and 860 nm. At 805 nm the laser pulse mainly excited the accessory BChls, although there was also the possibility of a small amount of excitation of P via the high energy exciton component of the Qy transition of the dimer. At 860 nm the laser pulse selectively excited the P BChls. A global analysis of each of the data sets using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes showed five EADS representing the time-evolution of the system (data not shown). The resulting lifetimes were very similar in the data sets collected with 805, 860 nm, and 600-nm excitation (Table 1). For the four slower components the EADS resulting from a global analysis of the data sets obtained with 805 and 860 nm excitation (data not shown) were very similar to the spectra presented in Fig. 2.

Reaction centers assembled without QA: selective excitation at 860 nm

Charge separation in RCs with an alanine (Ala) to tryptophan (Trp) mutation of residue M260 in the binding pocket of the QA ubiquinone was also investigated using 860 nm excitation. A combination of kinetic spectroscopy, x-ray crystallography, and FTIR spectroscopy has shown that the introduction of a bulky tryptophan residue in the QA binding pocket causes this AM260W RC to assemble without a QA quinone (30–32,50). Despite this, the structure of the RC outside the immediate vicinity of the QA pocket is not altered and the kinetics of electron transfer from P to HL are not affected (30). In agreement with this the data obtained for AM260W mutant RCs upon excitation with 860 nm light were very similar to those obtained with the QA-removed R26 RCs, a global analysis of the data yielding five EADS with lifetimes of 0.1 ps, 3 ps, 17 ps, 430 ps, and a nondecaying component (Table 1). The longest-lived component (430 ps) was ascribed to the ( )2 state. The nature of the nondecaying spectrum is not totally clear. Recently we have carried out a more detailed analysis of the spectral evolution in AM260W RCs and concluded that a further relaxation of (

)2 state. The nature of the nondecaying spectrum is not totally clear. Recently we have carried out a more detailed analysis of the spectral evolution in AM260W RCs and concluded that a further relaxation of ( )2 occurs on a timescale of ∼500 ps to form (

)2 occurs on a timescale of ∼500 ps to form ( )3, and this will be described in more detail in a future publication (N. P. Pawlowicz , I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. Breton, M. L. Groot , R. van Grondelle, M. R. Jones, unpublished). The lineshapes of these spectra (data not shown) were similar to those obtained with 860 nm excitation of QA removed RCs.

)3, and this will be described in more detail in a future publication (N. P. Pawlowicz , I. H. M. van Stokkum, J. Breton, M. L. Groot , R. van Grondelle, M. R. Jones, unpublished). The lineshapes of these spectra (data not shown) were similar to those obtained with 860 nm excitation of QA removed RCs.

The summary of the attribution of the various states in the data sets obtained on excitation of the QA-deficient RCs at 805 nm and 860 nm is shown in Table 1. The first picosecond timescale EADS was attributed to P*. The next state represents a mixture of mainly ( )1 with some contribution from

)1 with some contribution from  The longest-lived component was ascribed to the

The longest-lived component was ascribed to the  state, whereas the nondecaying components still contained mainly contributions from the relaxed form

state, whereas the nondecaying components still contained mainly contributions from the relaxed form  Due to the limited time range of the experiment of 3 ns, no evidence of 3P state formation was observed in these EADS.

Due to the limited time range of the experiment of 3 ns, no evidence of 3P state formation was observed in these EADS.

Reaction centers with QA removed: high spectral resolution with 805 nm excitation

The absorption changes after 805 nm excitation of R26 RCs lacking QA were also measured in 1783–1693 cm−1 range with a spectral resolution of 3 cm−1, as opposed to the 6 cm−1 resolution applicable to the spectra discussed in the last three sections. This was done to provide more detailed information on the two forms of  observed in steady-state FTIR measurements (44). The attributions are summarized in Table 2. As can be seen in Fig. 3, in the mid-IR spectra of both the

observed in steady-state FTIR measurements (44). The attributions are summarized in Table 2. As can be seen in Fig. 3, in the mid-IR spectra of both the  and

and  states (green and blue spectra, respectively) three negative bands were resolved in the C=O region of 10a-ester modes of

states (green and blue spectra, respectively) three negative bands were resolved in the C=O region of 10a-ester modes of  at 1733, 1739, and 1746 cm−1. Two of these wavelengths were similar to those obtained by steady-state FTIR spectroscopy with 4 cm−1 spectral resolution (44). The light-induced FTIR difference spectrum of

at 1733, 1739, and 1746 cm−1. Two of these wavelengths were similar to those obtained by steady-state FTIR spectroscopy with 4 cm−1 spectral resolution (44). The light-induced FTIR difference spectrum of  shows two bands related to free and H-bonded modes in the 10a-ester region of HL, at 1732 and 1747 cm−1, respectively (44), whereas only one band at 1743 cm−1 is found in the FTIR difference spectrum of isolated BPhe in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent (44). Following the same arguments, the 1746 and 1733 cm−1 negative bands observed in the green and blue spectra in Fig. 3 could correspond to a free and H-bonded conformer of the 10a ester C=O group of HL, respectively, with Trp L100 acting as the H-bond donor (43,50).

shows two bands related to free and H-bonded modes in the 10a-ester region of HL, at 1732 and 1747 cm−1, respectively (44), whereas only one band at 1743 cm−1 is found in the FTIR difference spectrum of isolated BPhe in tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent (44). Following the same arguments, the 1746 and 1733 cm−1 negative bands observed in the green and blue spectra in Fig. 3 could correspond to a free and H-bonded conformer of the 10a ester C=O group of HL, respectively, with Trp L100 acting as the H-bond donor (43,50).

FIGURE 3.

R26 RCs lacking QA excited at 805 nm and probed using a spectral resolution of 3 cm−1. The EADS are the result of a global analysis of the data using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes of 2.6 ps, 7.2 ps, 1.7 ns, and 4 ns.

As discussed above, the negative band at 1739 cm−1 in the spectra of  and

and  in Fig. 3 is attributable to the 10a ester C=O of PL/PM, with the positive band at 1751 cm−1 corresponding to the 10a ester C=O of

in Fig. 3 is attributable to the 10a ester C=O of PL/PM, with the positive band at 1751 cm−1 corresponding to the 10a ester C=O of  These frequencies match closely values from steady-state FTIR spectroscopy of 1740 cm−1 (negative) and 1750 cm−1 (positive) (39–41,45).

These frequencies match closely values from steady-state FTIR spectroscopy of 1740 cm−1 (negative) and 1750 cm−1 (positive) (39–41,45).

Reaction centers with QA removed: spectral changes in four other frequency ranges on 600 nm excitation

Experiments were also carried out on R26 RCs lacking QA in four other partly overlapping frequency regions. These were 2254–2060 cm−1, 2160–1930 cm−1, and 1908–1736 cm−1, each with a spectral resolution of 6 cm−1, and 2280–2111 cm−1 with a higher resolution of 3 cm−1. The excitation wavelength was 600 nm in each case. Each frequency region was analyzed separately, resulting in two EADS that are shown in Fig. 4. Also shown on the same scale are spectra covering the 1780–1600 cm−1 region (these are the EADS shown on an expanded scale in Fig. 2). The region between 2153 and 2075 cm−1 is not shown due to the high IR absorption by D2O. This D2O feature aside, no sharp spectral features were found in the frequency regions between 2280 and 1780 cm−1, but nevertheless the fitted lifetimes associated with these EADS were consistent with those found in the 1780–1600 cm−1 region.

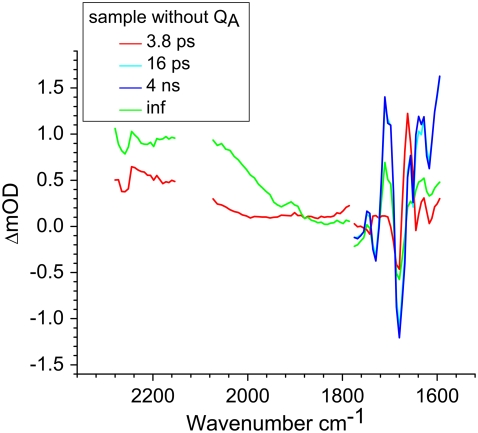

FIGURE 4.

EADS of R26 RCs lacking QA calculated from measurements carried out over a broad spectral range between 2280–1600 cm−1. The spectra between 2153–2075 cm−1 are not shown due to the high IR absorption by D2O in this region. The lifetimes shown are the result of global analysis of the data obtained in 1780–1600 cm−1 region (Fig. 2). Excitation was at 600 nm in each case.

In the region above 1780 cm−1 only two components were seen in the analysis, a component with a lifetime of 3.8 ps attributed to the P* state (red) and a nondecaying component attributed to the final  state (green). The positive feature between 1880 and 2247 cm−1 in the spectrum of this

state (green). The positive feature between 1880 and 2247 cm−1 in the spectrum of this  state is the shoulder of the broad positive band that has been attributed to an electronic transition (hole transfer) within the P+ dimer (51), and its position measures the resonance interaction between the two BChl molecules when P is oxidized. This attribution was made on the basis of the absence of this band in spectra of monomeric BChl a in THF (44) and its absence in the spectra of mutants in which either PL or PM was replaced by BPhe a (23,44,51). The measured transition energy and dipole strength of the band yields the resonance interaction matrix element that causes the remaining unpaired electron of P+ to move back and forth between PL and PM, and the energy difference between the two states in which a positive charge is fully localized on either PL or PM (51). From FTIR experiments that yielded a light-minus-dark

state is the shoulder of the broad positive band that has been attributed to an electronic transition (hole transfer) within the P+ dimer (51), and its position measures the resonance interaction between the two BChl molecules when P is oxidized. This attribution was made on the basis of the absence of this band in spectra of monomeric BChl a in THF (44) and its absence in the spectra of mutants in which either PL or PM was replaced by BPhe a (23,44,51). The measured transition energy and dipole strength of the band yields the resonance interaction matrix element that causes the remaining unpaired electron of P+ to move back and forth between PL and PM, and the energy difference between the two states in which a positive charge is fully localized on either PL or PM (51). From FTIR experiments that yielded a light-minus-dark  difference spectrum it was found that this hole transfer band is in fact centered at 2600 ± 100 cm−1 (51–53) and is not shifted in D2O (51). In previous experiments where a pure

difference spectrum it was found that this hole transfer band is in fact centered at 2600 ± 100 cm−1 (51–53) and is not shifted in D2O (51). In previous experiments where a pure  difference spectrum was generated in D2O no contribution to the 2600 cm−1 feature was found, showing it to arise from the P+ component (41,51,54). This 2600 cm−1 band is also absent in the difference spectrum of monomeric BChl a+/BChl a in solvent (44) and in the

difference spectrum was generated in D2O no contribution to the 2600 cm−1 feature was found, showing it to arise from the P+ component (41,51,54). This 2600 cm−1 band is also absent in the difference spectrum of monomeric BChl a+/BChl a in solvent (44) and in the  FTIR difference spectra of mutants with a heterodimeric BChl:BPhe primary donor, so it has been assigned to the dimeric nature of the oxidized primary donor P+ (23,44,51). In the work of Walker et al. (23) the time evolution of the 2600 cm−1 band was studied with a subpicosecond resolution and compared with measurements of the electron transfer rate in the RC. The P+ transition appeared in 3.4 ps, coincident with decay of the P* state, and was assigned to a transition between the symmetric and antisymmetric combination of the localized hole states of the dimer (23). The spectral kinetics and measured anisotropy of the transition permitted a direct verification of the nature of the eigenstates of P+ (23). The fs IR experiments reported here showed the significant charge transfer character of P* in agreement with for example findings of Lockhart and Boxer (55,56) based on Stark spectroscopy. The broad featureless band appears within the time resolution of the experiment and the signal approximately doubled in size with a time constant of 3.8 ps, in contrast to the findings of Walker et al. (23), where this signal was observed to rise concomitant with the appearance of P+ in 3.4 ps, indicating no charge transfer character of P*.

FTIR difference spectra of mutants with a heterodimeric BChl:BPhe primary donor, so it has been assigned to the dimeric nature of the oxidized primary donor P+ (23,44,51). In the work of Walker et al. (23) the time evolution of the 2600 cm−1 band was studied with a subpicosecond resolution and compared with measurements of the electron transfer rate in the RC. The P+ transition appeared in 3.4 ps, coincident with decay of the P* state, and was assigned to a transition between the symmetric and antisymmetric combination of the localized hole states of the dimer (23). The spectral kinetics and measured anisotropy of the transition permitted a direct verification of the nature of the eigenstates of P+ (23). The fs IR experiments reported here showed the significant charge transfer character of P* in agreement with for example findings of Lockhart and Boxer (55,56) based on Stark spectroscopy. The broad featureless band appears within the time resolution of the experiment and the signal approximately doubled in size with a time constant of 3.8 ps, in contrast to the findings of Walker et al. (23), where this signal was observed to rise concomitant with the appearance of P+ in 3.4 ps, indicating no charge transfer character of P*.

Reaction centers containing QA: nonselective excitation at 600 nm

To characterize the normal end product of membrane-spanning electron transfer, the state  R26 RCs containing QA were nonselectively excited at 600 nm, and data recorded in the frequency range 1590–1775 cm−1. The EADS generated by global analysis of the data set are shown in Fig. 5 (note that the ∼100 fs component is not shown). The obtained lifetimes are reported in Table 1 and band attributions for

R26 RCs containing QA were nonselectively excited at 600 nm, and data recorded in the frequency range 1590–1775 cm−1. The EADS generated by global analysis of the data set are shown in Fig. 5 (note that the ∼100 fs component is not shown). The obtained lifetimes are reported in Table 1 and band attributions for  are summarized in Table 2. Electron transfer from

are summarized in Table 2. Electron transfer from  to QA was observed to occur with a lifetime of 222 ps, forming

to QA was observed to occur with a lifetime of 222 ps, forming  (blue spectrum). This final nondecaying EADS (blue spectrum) showed clear differences from the 222 ps component (green) in the 1675–1610 cm−1 region, where the absorption changes are attributable to a variety of contributions that include the protein responses to charge separation.

(blue spectrum). This final nondecaying EADS (blue spectrum) showed clear differences from the 222 ps component (green) in the 1675–1610 cm−1 region, where the absorption changes are attributable to a variety of contributions that include the protein responses to charge separation.

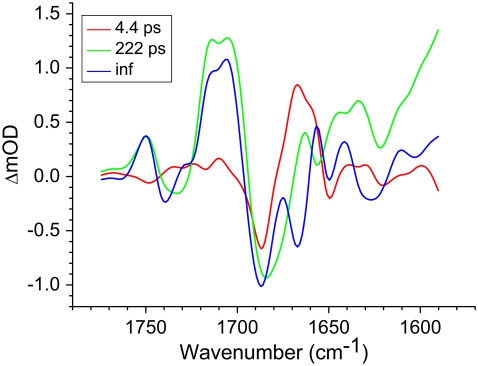

FIGURE 5.

R26 RCs with QA excited at 600 nm and probed in the region 1775–1590 cm−1. Displayed are EADS resulting from a global analysis using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes of 0.1 ps, 4.4 ps, 222 ps, and a nondecaying component.

The spectrum of the 222 ps component was similar to those obtained for the  state in the experiments described above with RCs lacking QA (Fig. 2). The nondecaying spectrum (Fig. 5, blue) was attributable to the state

state in the experiments described above with RCs lacking QA (Fig. 2). The nondecaying spectrum (Fig. 5, blue) was attributable to the state  with the 1675–1610 cm−1 region showing a pattern that is characteristic for contributions from

with the 1675–1610 cm−1 region showing a pattern that is characteristic for contributions from  (39,41,57,58), with bands that were negative at 1666 cm−1, positive at 1656 cm−1, negative at 1650 cm−1, positive at 1640 cm−1, and negative around 1630 and 1600 cm−1. The 1666(−)/1656(+) signal has been ascribed to a change in a protein amide I transition (21), whereas the 1650(−)/1640(+) signal has been attributed to the response of a protein backbone C=O that is connected to QA via an H-bond that is perturbed upon reduction of QA (39,45,59). An H-bond between the carbonyl of QA and the peptide N-H of Ala M260 residue is inferred from the x-ray crystal structure of the Rb. sphaeroides RC (40,45). In agreement with this, the band at 1650 cm−1 is present in the

(39,41,57,58), with bands that were negative at 1666 cm−1, positive at 1656 cm−1, negative at 1650 cm−1, positive at 1640 cm−1, and negative around 1630 and 1600 cm−1. The 1666(−)/1656(+) signal has been ascribed to a change in a protein amide I transition (21), whereas the 1650(−)/1640(+) signal has been attributed to the response of a protein backbone C=O that is connected to QA via an H-bond that is perturbed upon reduction of QA (39,45,59). An H-bond between the carbonyl of QA and the peptide N-H of Ala M260 residue is inferred from the x-ray crystal structure of the Rb. sphaeroides RC (40,45). In agreement with this, the band at 1650 cm−1 is present in the  FTIR difference spectra of Rb. sphaeroides and Rhodopseudomonas viridis RCs (41).

FTIR difference spectra of Rb. sphaeroides and Rhodopseudomonas viridis RCs (41).

In the 10a-ester region a set of bands were observed in the  EADS (Fig. 5, blue) that were somewhat different from those seen in preceding

EADS (Fig. 5, blue) that were somewhat different from those seen in preceding  EADS (Fig. 5, green). Both spectra showed bands attributable to the 9-keto C=O of PLPM,

EADS (Fig. 5, green). Both spectra showed bands attributable to the 9-keto C=O of PLPM,  and

and  at 1687(−), 1705(+), and 1715(+) cm−1, respectively, and a differential feature at 1739(−)/1750(+) attributed to the 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and

at 1687(−), 1705(+), and 1715(+) cm−1, respectively, and a differential feature at 1739(−)/1750(+) attributed to the 10a-ester C=O of PL/PM and  respectively. However an additional small positive band was seen at 1728 cm−1 in the

respectively. However an additional small positive band was seen at 1728 cm−1 in the  EADS (Fig. 5, blue) that has been ascribed in

EADS (Fig. 5, blue) that has been ascribed in  FTIR difference spectra to a shift of the 10a-ester C=O of HL in response to the electric field created by

FTIR difference spectra to a shift of the 10a-ester C=O of HL in response to the electric field created by  (60). As a general point, complex signals appear in this region due to heterogeneity in the conformation and hydrogen bonding of the 10a-ester C=O of HL, and this heterogeneity may be related to the functional heterogeneity observed in electron transfer kinetics.

(60). As a general point, complex signals appear in this region due to heterogeneity in the conformation and hydrogen bonding of the 10a-ester C=O of HL, and this heterogeneity may be related to the functional heterogeneity observed in electron transfer kinetics.

R26 RCs containing QA: selective excitation at 860 nm

R26 RCs with an intact QA were also excited at 860 nm and probed in the region 1780–1590 cm−1. On the basis of global analysis using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes three EADS were resolved, with associated lifetimes of 3.6 ps (P*), 280 ps  and a nondecaying component

and a nondecaying component  (Table 1). The lineshapes of the EADS (data not shown) were similar to those obtained for the equivalent states in the experiment with 600 nm excitation. Again, the nondecaying component showed bands related to a protein backbone C=O that is connected to QA at 1650(−)/1640(+), and a downshift of the 1666 cm−1 band to 1656 cm−1 in the amide I absorption range.

(Table 1). The lineshapes of the EADS (data not shown) were similar to those obtained for the equivalent states in the experiment with 600 nm excitation. Again, the nondecaying component showed bands related to a protein backbone C=O that is connected to QA at 1650(−)/1640(+), and a downshift of the 1666 cm−1 band to 1656 cm−1 in the amide I absorption range.

Summary of lifetimes obtained from global analysis

To summarize the results obtained in the individual experiments, all the lifetimes resulting from the global analysis of experimental data are listed in Table 1. As can be seen the lifetimes of the states resulting from independent global analysis were similar across the eight sets of data. The lifetimes associated with the EADS attributed to P* ranged between 2.6 ps and 4.4 ps. The lifetimes associated with the EADS attributed to the first charge separated state  in RCs lacking QA were also in good agreement, ranging from 7.2 ps to 17 ps. Finally the lifetimes associated with the EADS attributed to the second charge separated state

in RCs lacking QA were also in good agreement, ranging from 7.2 ps to 17 ps. Finally the lifetimes associated with the EADS attributed to the second charge separated state  in RCs with an intact QA were 222 ps and 280 ps for 600 nm and 860 nm excitation, respectively.

in RCs with an intact QA were 222 ps and 280 ps for 600 nm and 860 nm excitation, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the following we discuss several key points resulting from the analysis of this experimental data. The first major point of the discussion is the target analysis using the kinetic model that provided the best possible fit to the data. A difference spectrum for  is extracted and its details are discussed. In addition consideration is given to the agreement between lifetimes resulting from the data and those extracted from similar kinetic models applied previously, including those that assume direct charge separation from BL*. The discussion then examines the agreement between the fs time-resolved mid-IR spectra of the

is extracted and its details are discussed. In addition consideration is given to the agreement between lifetimes resulting from the data and those extracted from similar kinetic models applied previously, including those that assume direct charge separation from BL*. The discussion then examines the agreement between the fs time-resolved mid-IR spectra of the  and

and  states and the sum of steady state FTIR spectra measured previously for

states and the sum of steady state FTIR spectra measured previously for  and

and  Features specific for the reduction of HL and QA observed in fs time-resolved spectra are assigned, as are changes in protein conformation due to the electron transfer. Finally the issue of charge delocalization on the primary electron donor is discussed.

Features specific for the reduction of HL and QA observed in fs time-resolved spectra are assigned, as are changes in protein conformation due to the electron transfer. Finally the issue of charge delocalization on the primary electron donor is discussed.

Target analysis of the seven data sets using a single model

The global analysis using a sequential model with increasing lifetimes described above gave very good fits to the seven sets of experimental data, but it has the disadvantage that it does not take into account the multi-exponential nature of the decay of the P* state or the documented involvement of  in electron transfer from P* to HL. To further disentangle the contributions of various states to the observed spectral evolution a simultaneous target analysis of all data sets was carried out. This analysis accounted for the multi-exponential decay of P* emission by including back reactions, and included a

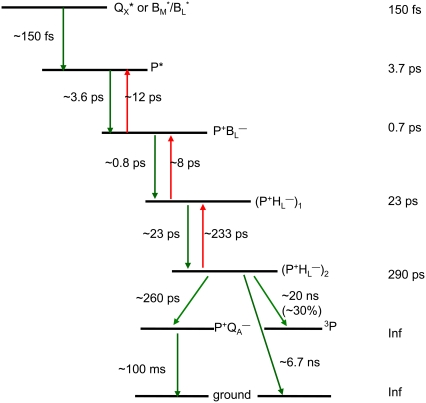

in electron transfer from P* to HL. To further disentangle the contributions of various states to the observed spectral evolution a simultaneous target analysis of all data sets was carried out. This analysis accounted for the multi-exponential decay of P* emission by including back reactions, and included a  intermediate. On the basis of the sequential analysis presented above, and results from the literature obtained in visible region pump/probe experiments, rate constants for the forward and backward reactions were estimated and the full kinetic scheme depicted in Fig. 6 was obtained. According to this scheme the decay of the P* state is four-exponential, proceeding through the states

intermediate. On the basis of the sequential analysis presented above, and results from the literature obtained in visible region pump/probe experiments, rate constants for the forward and backward reactions were estimated and the full kinetic scheme depicted in Fig. 6 was obtained. According to this scheme the decay of the P* state is four-exponential, proceeding through the states  and

and  This kinetic scheme was similar to that used in previous reports to analyze visible-region pump-probe data (18) and the lifetimes obtained in this study were in good agreement with those obtained in a number of published studies (12,61–64).

This kinetic scheme was similar to that used in previous reports to analyze visible-region pump-probe data (18) and the lifetimes obtained in this study were in good agreement with those obtained in a number of published studies (12,61–64).

FIGURE 6.

Scheme for energy transfer and electron transfer in R26 and AM260W RCs. Green arrows (plus associated time constants) refer to forward processes, red arrows to back reactions. Forward electron transfer from the  state in RCs with QA led to the

state in RCs with QA led to the  state, whereas in QA-deficient RCs it led to the triplet state of P (3P) and recombination to the ground state.

state, whereas in QA-deficient RCs it led to the triplet state of P (3P) and recombination to the ground state.

The kinetic model shown in Fig. 6 was applied simultaneously to all of the data sets described above, resulting in lifetimes of 150 fs, 3.7 ps, 0.7 ps, 23 ps, 290 ps, and two nondecaying components. The initially excited states Qx* and BL*/BM*, observed on excitation at 600 nm and 805 nm, respectively, are formed during the laser pulse. Energy transfer from BL*/BM* to P taking place in ∼150 fs after direct excitation of the accessory BChls was poorly resolved in our experiments (in addition there is the possibility of a small amount of direct charge separation from BL*, but for simplicity this was not included in the model). The P* state decays in 3.7 ps by charge separation to form  and this subsequently decays in 0.7 ps to form the

and this subsequently decays in 0.7 ps to form the  state. The next component, with a decay time of 23 ps, is relaxation of

state. The next component, with a decay time of 23 ps, is relaxation of  into

into  Decay of

Decay of  occurs in one of two ways, depending on whether or not the sample contains QA. In case of RCs with QA the

occurs in one of two ways, depending on whether or not the sample contains QA. In case of RCs with QA the  state decays in 290 ps to

state decays in 290 ps to  which is represented by a nondecaying component.

which is represented by a nondecaying component.  decays on a timescale of ms, which is assumed to be infinite taking into account the time range of our experiment. In case of RCs without QA the

decays on a timescale of ms, which is assumed to be infinite taking into account the time range of our experiment. In case of RCs without QA the  state decays in ∼20 ns, ∼30% into the triplet state of the primary electron donor (3P) and the other fraction recombines to the ground state of P in ∼6.7 ns.

state decays in ∼20 ns, ∼30% into the triplet state of the primary electron donor (3P) and the other fraction recombines to the ground state of P in ∼6.7 ns.

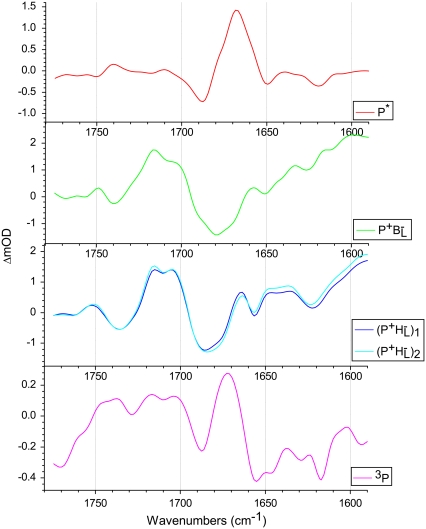

A representative set of species associated decay spectra (SADS) resulting from the target analysis are shown in Fig. 7 (again the SADS corresponding to the ultrafast ∼150 fs component was not shown). These SADS are derived from the data obtained with R26 RCs lacking QA that had been excited at 805 nm. The red spectrum, which is attributed to P* shows a negative band at 1687 cm−1 that is ascribed to the 9-keto modes of PL and PM in the ground state, and this downshifts to 1668 cm−1 in the excited state.

FIGURE 7.

SADS derived from data obtained with R26 RCs lacking QA that had been excited at 805 nm. The SADS were produced from a target analysis of all data sets using the kinetic scheme outlined in Fig. 6.

The green spectrum in Fig. 7 is that of the first intermediate in charge separation,  Due to its short lifetime and, as a consequence, low population it was difficult to detect the state

Due to its short lifetime and, as a consequence, low population it was difficult to detect the state  in the time-resolved difference spectra. For the same reasons the level of uncertainty in the

in the time-resolved difference spectra. For the same reasons the level of uncertainty in the  SADS in Fig. 7 is greater than in the remaining spectra, but nevertheless this spectrum was generally reproducible in the simultaneous target analysis of the seven data sets (see below). This spectrum contains the ground state bleaching of P around 1687 cm−1 plus an additional bleaching in the 1670–1680 cm−1 region that can be ascribed to BL. It is possible that the small positive band at 1657 cm−1 is attributable to the 9-keto C=O of the anion state of BL that would be consistent with the general picture that the stretching frequency of a keto C=O undergoes a downshift on reduction of a cofactor (44). In addition, it is likely that any shift of the stretching frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL on formation of

SADS in Fig. 7 is greater than in the remaining spectra, but nevertheless this spectrum was generally reproducible in the simultaneous target analysis of the seven data sets (see below). This spectrum contains the ground state bleaching of P around 1687 cm−1 plus an additional bleaching in the 1670–1680 cm−1 region that can be ascribed to BL. It is possible that the small positive band at 1657 cm−1 is attributable to the 9-keto C=O of the anion state of BL that would be consistent with the general picture that the stretching frequency of a keto C=O undergoes a downshift on reduction of a cofactor (44). In addition, it is likely that any shift of the stretching frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL on formation of  is complicated by changes arising from oxidation of the immediately adjacent P BChls, in addition to effects due to the reduction of BL. On the basis of resonance Raman studies (65), the frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL in the ground state is thought to be in the region of 1687 cm−1 and downshifts to 1675 cm−1 in RCs where P is chemically oxidized as a result of the formation of a moderate strength H-bond, or strengthening of a weak H-bond. In Robert and Lutz (65) the H-bond donor was suggested to be a water molecule, and this was confirmed in a subsequent study that showed that this P+-induced downshift was lost in structurally-characterized mutant reaction centers in which this water molecule was absent (66). It is therefore possible that any shift in the stretching frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL on formation of

is complicated by changes arising from oxidation of the immediately adjacent P BChls, in addition to effects due to the reduction of BL. On the basis of resonance Raman studies (65), the frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL in the ground state is thought to be in the region of 1687 cm−1 and downshifts to 1675 cm−1 in RCs where P is chemically oxidized as a result of the formation of a moderate strength H-bond, or strengthening of a weak H-bond. In Robert and Lutz (65) the H-bond donor was suggested to be a water molecule, and this was confirmed in a subsequent study that showed that this P+-induced downshift was lost in structurally-characterized mutant reaction centers in which this water molecule was absent (66). It is therefore possible that any shift in the stretching frequency of the 9-keto C=O of BL on formation of  arises both from the reduction of BL, and also a change in the strength of any hydrogen bond interaction between this C=O group and the adjacent water molecule. On the other hand, on the basis of the FTIR difference spectrum of BChl a anion in THF (67) the 9-keto

arises both from the reduction of BL, and also a change in the strength of any hydrogen bond interaction between this C=O group and the adjacent water molecule. On the other hand, on the basis of the FTIR difference spectrum of BChl a anion in THF (67) the 9-keto  mode was assigned to be downshifted from 1683 cm−1 to 1620 cm−1. For this reason, it is also possible that the broad positive feature around 1600 cm−1 in fs mid-IR

mode was assigned to be downshifted from 1683 cm−1 to 1620 cm−1. For this reason, it is also possible that the broad positive feature around 1600 cm−1 in fs mid-IR  spectrum represents the downshifted BL 9-keto in the anion state similar to the frequency reported in (67). Furthermore, the differential signals in the region between 1650 and 1600 cm−1 could not be attributed with certainty, as multiple contributions are expected in this region from the acetyl C=O groups of P and B and protein C=O groups. These attributions of the 1670–1680(−)/1657(+) cm−1 and/or 1600(+) cm−1 modes to the 9-keto C=O of

spectrum represents the downshifted BL 9-keto in the anion state similar to the frequency reported in (67). Furthermore, the differential signals in the region between 1650 and 1600 cm−1 could not be attributed with certainty, as multiple contributions are expected in this region from the acetyl C=O groups of P and B and protein C=O groups. These attributions of the 1670–1680(−)/1657(+) cm−1 and/or 1600(+) cm−1 modes to the 9-keto C=O of  are only tentative at this stage and will require further investigation, possibly using the mutant reaction centers described above in which the water molecule adjacent to this group is excluded (66).

are only tentative at this stage and will require further investigation, possibly using the mutant reaction centers described above in which the water molecule adjacent to this group is excluded (66).

The negative band at 1739 cm−1 that upshifts to give a positive band at 1750 cm−1 in the SADS of  is attributable to the upshift of the mode of the 10a-ester C=O of P station formation of P+ (39). The positive band at 1715 cm−1 is attributable to the 9-keto C=O of

is attributable to the upshift of the mode of the 10a-ester C=O of P station formation of P+ (39). The positive band at 1715 cm−1 is attributable to the 9-keto C=O of  and, remarkably, the band of the 9-keto C=O of

and, remarkably, the band of the 9-keto C=O of  at 1705 cm−1 is significantly diminished. The most likely reason is a perturbed distribution of the unpaired electron within P+ due to the nearby negative charge localized on BL with the main contribution coming from

at 1705 cm−1 is significantly diminished. The most likely reason is a perturbed distribution of the unpaired electron within P+ due to the nearby negative charge localized on BL with the main contribution coming from  Upon further transfer of the electron to HL its influence on the electron distribution within P+ is reduced, leading to an increase of the 9-keto band of

Upon further transfer of the electron to HL its influence on the electron distribution within P+ is reduced, leading to an increase of the 9-keto band of  at 1705 cm−1 in the

at 1705 cm−1 in the  states (Fig. 7, blue and cyan spectra).

states (Fig. 7, blue and cyan spectra).

The blue and cyan spectra in Fig. 7 represent the product of the second step of charge separation,  These SADS were similar to the corresponding EADS presented in the Results, and the attribution of the various bands is summarized in Table 2 (see Results for details). After electron transfer to HL in ∼0.7 ps, the

These SADS were similar to the corresponding EADS presented in the Results, and the attribution of the various bands is summarized in Table 2 (see Results for details). After electron transfer to HL in ∼0.7 ps, the  state was formed (Fig. 7, blue), which then relaxed with a lifetime of 23 ps to the

state was formed (Fig. 7, blue), which then relaxed with a lifetime of 23 ps to the  state (Fig. 7, cyan). Minor differences are apparent between these two spectra, mainly in the intensity of the bands at 1663(+) and 1656(−) cm−1 that have been ascribed to the response of an amide C=O (39), and the bands assigned to 9-keto modes of

state (Fig. 7, cyan). Minor differences are apparent between these two spectra, mainly in the intensity of the bands at 1663(+) and 1656(−) cm−1 that have been ascribed to the response of an amide C=O (39), and the bands assigned to 9-keto modes of  and

and  at 1705 and 1715 cm−1, respectively. Minor changes are also seen in the relative intensities of the product state bands at 1647 and 1635 cm−1. As the 2a-acetyl C=O modes of P upshift in the cation state, these positive bands are ascribed to the 2a-acetyl modes of

at 1705 and 1715 cm−1, respectively. Minor changes are also seen in the relative intensities of the product state bands at 1647 and 1635 cm−1. As the 2a-acetyl C=O modes of P upshift in the cation state, these positive bands are ascribed to the 2a-acetyl modes of  and

and  respectively, and the negative bands at 1642 cm−1 and 1624 cm−1 could correspond to the equivalent ground state modes of PM and PL (39). However, as discussed above, these attributions of the observed 2a-acetyl C=O modes are not certain due to other contributions that affect the region of this spectrum (21,22,39,44).

respectively, and the negative bands at 1642 cm−1 and 1624 cm−1 could correspond to the equivalent ground state modes of PM and PL (39). However, as discussed above, these attributions of the observed 2a-acetyl C=O modes are not certain due to other contributions that affect the region of this spectrum (21,22,39,44).

For RCs lacking QA,  is the last charge separated state, and the triplet state of P is formed in ∼7 ns (Fig. 7, magenta spectrum). The triplet state spectrum shows a negative band at 1687 cm−1 from a mode that downshifts to give a positive band at 1672 cm−1. This positive band at 1672 cm−1 is the most prominent in the 3P spectrum, and was also observed in an FTIR study conducted on RCs at 85 K (66). The presence of the negative band at 1687 cm−1 strongly supports the assignment of this 1672 cm−1 band to the 9-keto C=O groups of the P BChls.

is the last charge separated state, and the triplet state of P is formed in ∼7 ns (Fig. 7, magenta spectrum). The triplet state spectrum shows a negative band at 1687 cm−1 from a mode that downshifts to give a positive band at 1672 cm−1. This positive band at 1672 cm−1 is the most prominent in the 3P spectrum, and was also observed in an FTIR study conducted on RCs at 85 K (66). The presence of the negative band at 1687 cm−1 strongly supports the assignment of this 1672 cm−1 band to the 9-keto C=O groups of the P BChls.

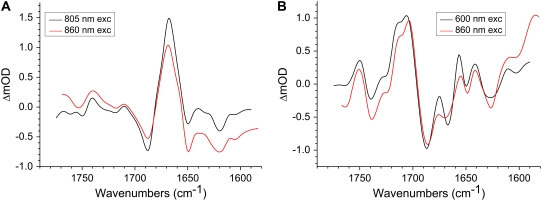

The final step of charge separation in RCs containing QA leads to formation of the  state in 290 ps. Two SADS of this state obtained with either 600 nm or 860 nm excitation are shown in Fig. 8 B. The 1675–1610 cm−1 region shows a pattern that is characteristic for contributions from

state in 290 ps. Two SADS of this state obtained with either 600 nm or 860 nm excitation are shown in Fig. 8 B. The 1675–1610 cm−1 region shows a pattern that is characteristic for contributions from  (39,41,57,58). The strong band shift signal at 1666(−)/1656(+) cm−1 has been ascribed to a protein response to the reduction of QA (58). The shoulder at 1728 cm−1 is assigned to the anion state of QA and has been observed previously in FTIR

(39,41,57,58). The strong band shift signal at 1666(−)/1656(+) cm−1 has been ascribed to a protein response to the reduction of QA (58). The shoulder at 1728 cm−1 is assigned to the anion state of QA and has been observed previously in FTIR  difference spectra together with a negative band at 1735 cm−1 (39,41,60) that is shifted to 1739 cm−1 in fs mid-IR spectrum, probably due to an overlap with 10a-ester modes of P.

difference spectra together with a negative band at 1735 cm−1 (39,41,60) that is shifted to 1739 cm−1 in fs mid-IR spectrum, probably due to an overlap with 10a-ester modes of P.

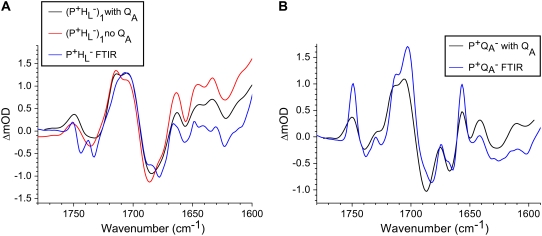

FIGURE 8.

Comparison of the P* and  spectra resulting from target analysis of R26 RCs. (A) P* state spectra resulting from excitation at 805 nm (black) and 860 nm (red). (B)

spectra resulting from target analysis of R26 RCs. (A) P* state spectra resulting from excitation at 805 nm (black) and 860 nm (red). (B)  spectra resulting from excitation at 600 nm (black) and 860 nm (red).

spectra resulting from excitation at 600 nm (black) and 860 nm (red).

In summary, the SADS obtained for the various states formed during charge separation contained features that correlated well with previous data from steady-state FTIR spectroscopy, and most spectral features could be assigned with reasonable confidence. The majority of features arose from frequency shifts associated with oxidation of P or reduction of BL, HL, or QA, with some additional components arising from the response of the protein. In the next section the reproducibility of the various spectra is considered by comparing SADS obtained from individual data sets.

Comparison of the P*, P+HL−, and P+QA− SADS resulting from a simultaneous target analysis of R26 and AM260W RCs

To show the reproducibility of the fs mid-IR experiments the P*,  and

and  spectra resulting from individual experiments on different samples were compared. These comparisons are shown in Fig. 8 A (P*), Fig. 8 B (

spectra resulting from individual experiments on different samples were compared. These comparisons are shown in Fig. 8 A (P*), Fig. 8 B ( ) and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1 and Data S1

) and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1 and Data S1  and

and

Fig. 8 A shows a comparison of the SADS corresponding to the P* state for R26 RCs excited at 805 nm (black) and 860 nm (red). The spectra are very similar with the main transition centered at 1668 cm−1. The SADS corresponding to the P* state derived from the remaining five data sets had similar line-shapes (not shown), and it was concluded that the spectral signature of this state was very reproducible, with relatively little distortion, apart from presence of some baseline noise.

Fig. 8 B shows SADS corresponding to the  state derived from data on R26 RCs excited at 600 nm (black) and 860 nm (red). The most noticeable difference between the two is the smaller amplitude of the signals observed at 1675(−) cm−1 and 1667(+)/1656(−) cm−1 in the red spectrum. Other than this, the two spectra show good correspondence.

state derived from data on R26 RCs excited at 600 nm (black) and 860 nm (red). The most noticeable difference between the two is the smaller amplitude of the signals observed at 1675(−) cm−1 and 1667(+)/1656(−) cm−1 in the red spectrum. Other than this, the two spectra show good correspondence.

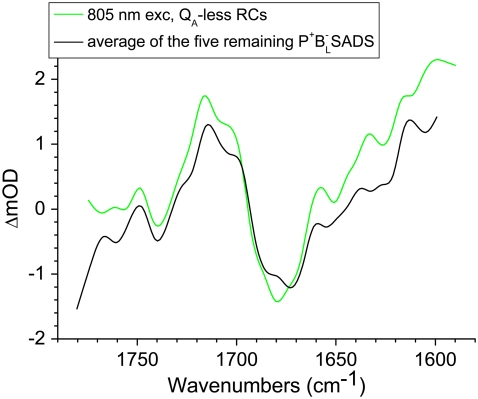

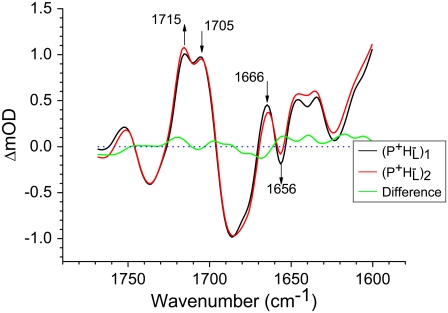

Fig. S1 and Data S1 shows the spectra of  (black) and