Abstract

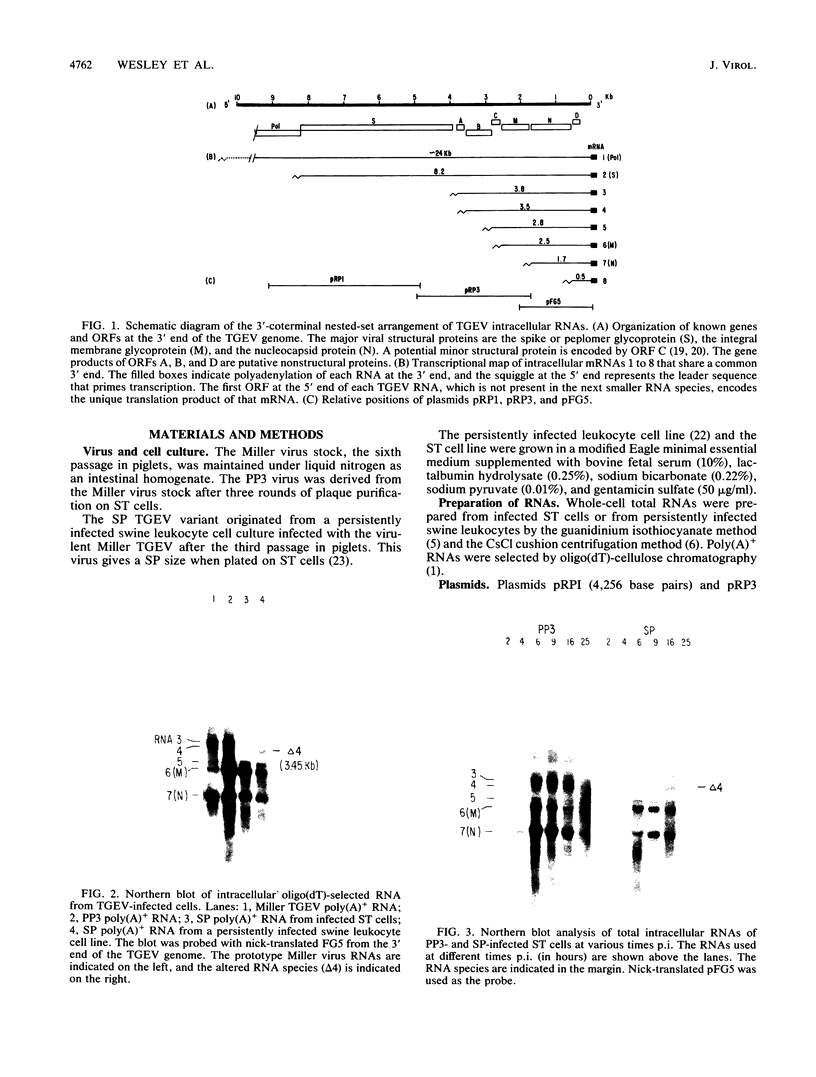

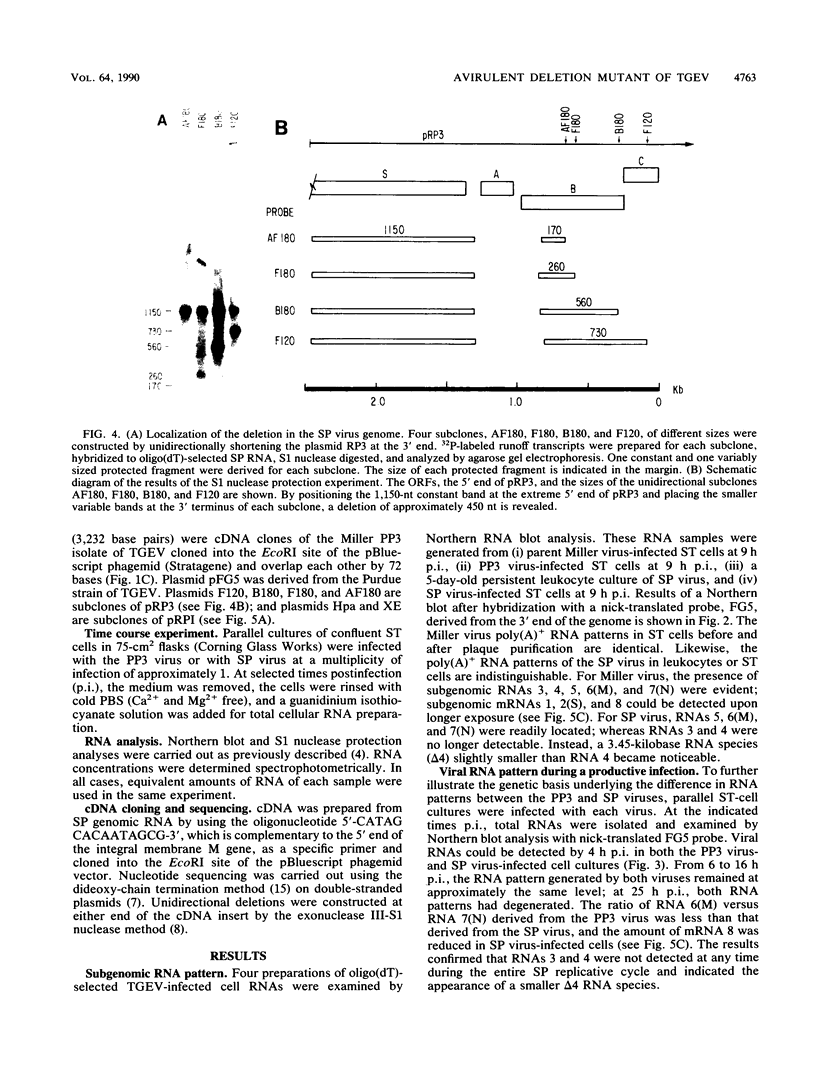

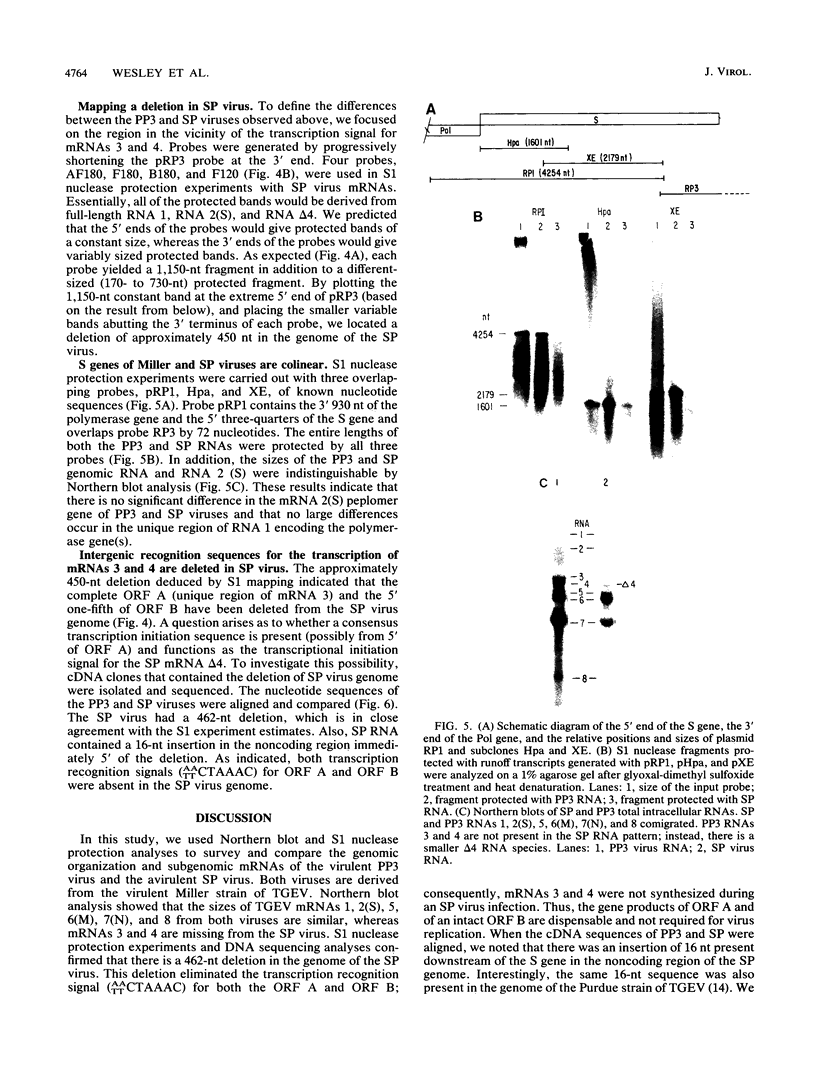

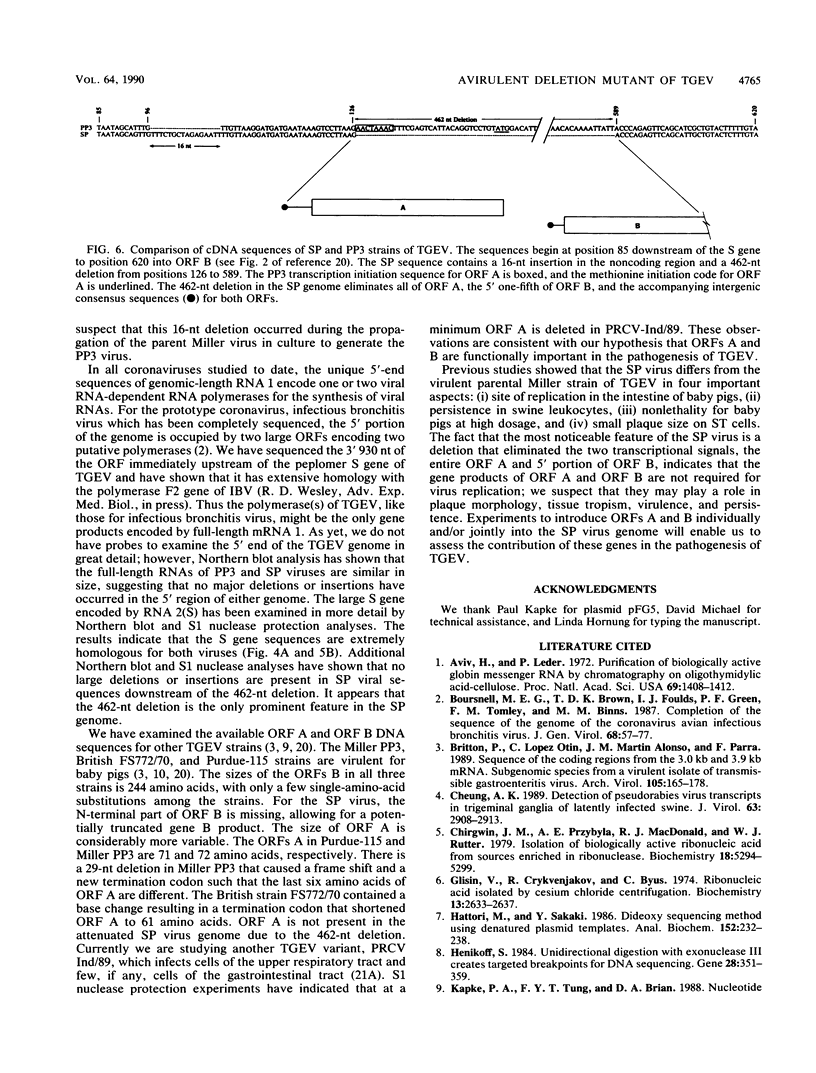

Intracellular RNAs of an avirulent small-plaque (SP) transmissible gastroenteritis virus variant and the parent virulent Miller strain of transmissible gastroenteritis virus were compared. Northern RNA blotting showed that the Miller strain contained eight intracellular RNA species. RNAs 1, 2(S), 5, 6(M), 7(N), and 8 were similar in size for both viruses; however, the SP variant lacked subgenomic RNAs 3 and 4. Instead, the SP virus contained an altered RNA species (delta 4) that was slightly smaller than RNA 4. S1 nuclease protection experiments showed a deletion of approximately 450 nucleotides in the SP genome downstream of the peplomer S gene. Sequencing of cDNA clones confirmed that SP virus contained a 462-nucleotide deletion, eliminating the transcriptional recognition sequences for both RNAs 3 and 4. These RNAs encode open reading frames A and B, respectively. An alternative consensus recognition sequence was not readily apparent for the delta 4 RNA species of SP virus. Since open reading frame A is missing in SP virus, it is not essential for a productive infection. The status of the potential protein encoded by open reading frame B is not clear, because it may be missing or just truncated. Nevertheless, these genes appear to be the contributing entities for transmissible gastroenteritis virus virulence, SP morphology, tissue tropism, and/or persistence in swine leukocytes.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aviv H., Leder P. Purification of biologically active globin messenger RNA by chromatography on oligothymidylic acid-cellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972 Jun;69(6):1408–1412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.6.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boursnell M. E., Brown T. D., Foulds I. J., Green P. F., Tomley F. M., Binns M. M. Completion of the sequence of the genome of the coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. J Gen Virol. 1987 Jan;68(Pt 1):57–77. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton P., Lopez Otin C., Martin Alonso J., Parra F. Sequence of the coding regions from the 3.0 kb and 3.9 kb mRNA. Subgenomic species from a virulent isolate of transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Arch Virol. 1989;105(3-4):165–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01311354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A. K. Detection of pseudorabies virus transcripts in trigeminal ganglia of latently infected swine. J Virol. 1989 Jul;63(7):2908–2913. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2908-2913.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirgwin J. M., Przybyla A. E., MacDonald R. J., Rutter W. J. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979 Nov 27;18(24):5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisin V., Crkvenjakov R., Byus C. Ribonucleic acid isolated by cesium chloride centrifugation. Biochemistry. 1974 Jun 4;13(12):2633–2637. doi: 10.1021/bi00709a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori M., Sakaki Y. Dideoxy sequencing method using denatured plasmid templates. Anal Biochem. 1986 Feb 1;152(2):232–238. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S. Unidirectional digestion with exonuclease III creates targeted breakpoints for DNA sequencing. Gene. 1984 Jun;28(3):351–359. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Bonnardière C., Laude H. Interferon induction in rotavirus and coronavirus infections: a review of recent results. Ann Rech Vet. 1983;14(4):507–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. M. Coronavirus leader-RNA-primed transcription: an alternative mechanism to RNA splicing. Bioessays. 1986 Dec;5(6):257–260. doi: 10.1002/bies.950050606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. M., Patton C. D., Baric R. S., Stohlman S. A. Presence of leader sequences in the mRNA of mouse hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1983 Jun;46(3):1027–1033. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.3.1027-1033.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. M., Patton C. D., Stohlman S. A. Replication of mouse hepatitis virus: negative-stranded RNA and replicative form RNA are of genome length. J Virol. 1982 Nov;44(2):487–492. doi: 10.1128/jvi.44.2.487-492.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasschaert D., Gelfi J., Laude H. Enteric coronavirus TGEV: partial sequence of the genomic RNA, its organization and expression. Biochimie. 1987 Jun-Jul;69(6-7):591–600. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki S. G., Sawicki D. L. Coronavirus transcription: subgenomic mouse hepatitis virus replicative intermediates function in RNA synthesis. J Virol. 1990 Mar;64(3):1050–1056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1050-1056.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethna P. B., Hung S. L., Brian D. A. Coronavirus subgenomic minus-strand RNAs and the potential for mRNA replicons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jul;86(14):5626–5630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddell S. G., Anderson R., Cavanagh D., Fujiwara K., Klenk H. D., Macnaughton M. R., Pensaert M., Stohlman S. A., Sturman L., van der Zeijst B. A. Coronaviridae. Intervirology. 1983;20(4):181–189. doi: 10.1159/000149390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaan W., Cavanagh D., Horzinek M. C. Coronaviruses: structure and genome expression. J Gen Virol. 1988 Dec;69(Pt 12):2939–2952. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-12-2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley R. D., Cheung A. K., Michael D. D., Woods R. D. Nucleotide sequence of coronavirus TGEV genomic RNA: evidence for 3 mRNA species between the peplomer and matrix protein genes. Virus Res. 1989 Jun;13(2):87–100. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(89)90008-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesley R. D., Woods R. D., Correa I., Enjuanes L. Lack of protection in vivo with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to transmissible gastroenteritis virus. Vet Microbiol. 1988 Dec;18(3-4):197–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90087-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. D., Cheville N. F., Gallagher J. E. Lesions in the small intestine of newborn pigs inoculated with porcine, feline, and canine coronaviruses. Am J Vet Res. 1981 Jul;42(7):1163–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. D. Leukocyte migration-inhibition procedure for transmissible gastroenteritis viral antigens. Am J Vet Res. 1977 Aug;38(8):1267–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. D. Small plaque variant transmissible gastroenteritis virus. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978 Sep 1;173(5 Pt 2):643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods R. D., Wesley R. D. Immune response in sows given transmissible gastroenteritis virus or canine coronavirus. Am J Vet Res. 1986 Jun;47(6):1239–1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]