Abstract

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) affects both leptomeningeal and parenchymal blood vessels and is common in Alzheimer's disease (AD). In some vessels, CAA is accompanied by localized neuritic dystrophy around the affected blood vessel. The aim of this study was to assess the distribution and severity of perivascular neuritic dystrophy in primary visual and visual association cortices. The severity of perivascular neuritic dystrophy and Aβ deposition was scored in an association cortex (Brodmann area 18) and a primary cortex (Brodmann area 17) with double labeling immunohistochemistry for tau and Aβ in 31 cases of AD with severe CAA. The perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy score was significantly worse in visual association cortex than in primary visual cortex. On the other hand, there was no difference in the perivascular Aβ score between the two cortices. There were positive correlations between the severity of perivascular tau and perivascular Aβ scores for both primary and association cortices. The results suggest that the local neuronal environment determines the severity and nature of the perivascular neuritic pathology more than the severity of the intrinsic vascular disease and suggest a close association between perivascular amyloid deposits, so-called dyshoric angiopathy, and perivascular neuritic dystrophy.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid angiopathy, Aβ, tau, neuritic dystrophy, visual cortex

Introduction

The neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is characterized by neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), neuropil threads (NTs), senile plaques (SPs) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Both SPs and CAA are composed of extracellular deposits of amyloid beta protein (Aβ) while NFTs and NTs are composed of intracellular deposits of microtubule associated tau protein. A number of studies have addressed the relationship of parenchymal Aβ deposits and tau pathology, but there are limited analyses of these relationships of tau pathology to Aβ vascular deposits. Clinicopathological studies have revealed that extracellular Aβ deposition in brain tissue is more poorly correlated with intellectual status than tau pathology [2–4]. This is in part due to the fact that some non-demented elderly individuals have many SPs, but minimal or no NFTs, a process that has been referred to as pathological aging [4]. SPs can be classified as neuritic and non-neuritic plaques, with diffuse plaques being a form of the latter. Neuritic plaques are characterized by amyloid deposits and surrounding tau neuritic dystrophy. Diffuse plaques, which are frequent in pathological aging, are characterized by non-compact amyloid deposits with no tau neuritic pathology. CAA affects both leptomeningeal and intraparenchymal blood vessels and is common in AD. In some vessels, CAA is accompanied by localized neuritic dystrophy around the affected blood vessel [1]. Perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy would not be predicted to occur in CAA in pathological aging given the absence of cortical tau pathology, but this has not been previously studied.

The distribution of CAA is not uniform; some investigators have noted CAA in the frontal lobe, but CAA is more frequent and severe in the occipital lobe [5]. Tau related pathology (i.e. NFTs and NTs) is more severe and occurs earlier in the disease process in association cortices (e.g., visual association cortex – Brodmann areas 18 and 19) compared to primary cortices (e.g., primary visual cortex – Brodmann area 17) [3, 6, 7]. In this study, we investigated the severity and distribution of tau immunoreactive perivascular neuritic dystrophy associated with CAA in visual and association cortices of AD.

Material and Methods

Selection of Cases

We investigated 31 cases of AD with severe CAA (19 men, 12 women; age of death, 80.0 ± 10.0 years; race 28 Caucasian, 2 African American and 1 Hispanic; brain weight 1052 ± 182 g) from the neuropathology files of Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, FL. The cases had undergone quantitative neuropathological assessments of SPs and NFTs in multiple cortical and subcortical sections with thioflavine-S fluorescent microscopy to assess Alzheimer-type pathology and to assign a Braak stage [6]. All cases fulfilled the NIA-Reagan criteria for AD [8], and all had many SPs and a Braak NFT stage of IV or greater (average: 5.6 ± 0.6).

To evaluate the severity of perivascular Aβ deposition, which is also referred to as dyshoric angiopathy, and tau neuritic dystrophy related to CAA, we performed double-labeling immunohistochemistry of tau and Aβ. Sections from paraffin embedded tissue of occipital cortex, including both visual and association cortices, were cut at a thickness of 5-μm. The deparaffinized and dehydrated sections were steamed for 30 minutes for antigen retrieval followed by blocking of endogenous peroxidase with 3% H2O2. The sections were then treated with 5% normal goat serum for 20 min. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with a phospho-tau monoclonal antibody, CP13 (which recognizes a phospho-epitope on tau at Ser 202 and generously supplied by Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) at room temperature for 45 min.

After incubation with the primary antibody, the sections were treated with Envision-Plus, Peroxidase, Mouse (DAKO, Santa Barbara, CA) for 30 min. Peroxidase labeling was visualized with a solution containing 0.02 mg/mL 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). After the DAB reaction of the first immunohistochemical cycle, the sections were treated with Doublestain block reagent (DAKO, Santa Barbara, CA) for 3 min. The second primary antibody, anti-pan Aβ (33.1.1; Todd Golde, Mayo Clinic) was then applied at room temperature for 45 min. The sections were then treated with alkaline phosphatase labeled polymer (DAKO, Santa Barbara, CA) for 30 min. Alkaline phosphatase labeling was detected with a chromogen solution containing 0.15 mg/mL of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (SIGMA, St. Louis, MO). The sections were dehydrated and coverslipped without counterstaining.

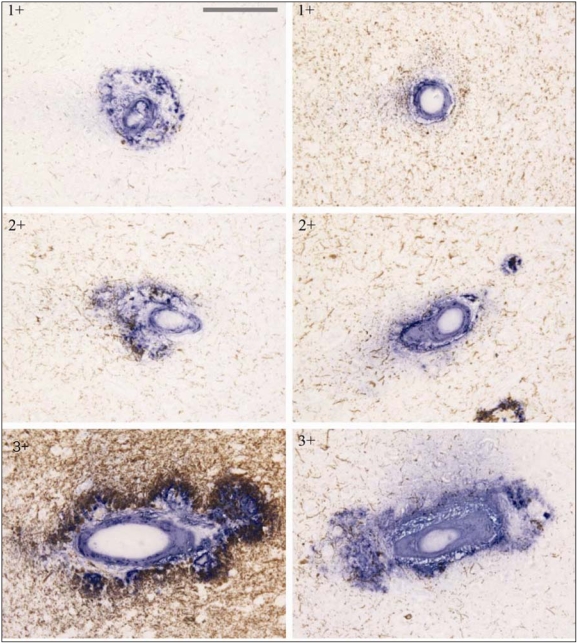

In each region (Brodmann areas 18 and 17) of each AD case, five blood vessels with CAA were randomly selected. To evaluate the severity of perivascular neuritic dystrophy and Aβ deposition related to CAA in the same blood vessels, neuritic tau pathology and Aβ deposition was scored for each vessel, as follows: perivascular neuritic dystrophy (Figure 1, left panel: 0 – absent; 1+ – rare, around vessel; 2+ – partially around vessel; 3+ – entirely around vessel); perivascular Aβ deposition (Figure 1, right panel: 1+ – only vessel, 2+ – vessel and parenchymal deposits partially around vessel; 3+ – vessel and parenchymal entirely around vessel).

Figure 1.

Representative visual fields showing perivascular neuritic tau pathology and amyloid deposition related to CAA with examples for severity score. Double immunostaining for Aβ (blue) and tau (brown). Left panel shows range of perivascular neuritic dystrophy, with tau (brown) related to CAA. Scores: 1+, 2+ and 3+ (as described in text). Right panel represents perivascular amyloid deposition (blue) related to CAA. Score 1+, 2+ and 3+ (as described in text) (Bar = 38 μm).

A mean score for each measure and region was calculated for each case. Statistical analyses were performed with SigmaStat (Systat Software, Inc., Point Richmond, CA), and the significance level was set at p<0.05. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess differences in perivascular Aβ and neuritic dystrophy scores between visual and association cortices. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlation between Aβ and neuritic dystrophy scores in the two cortical regions.

Results

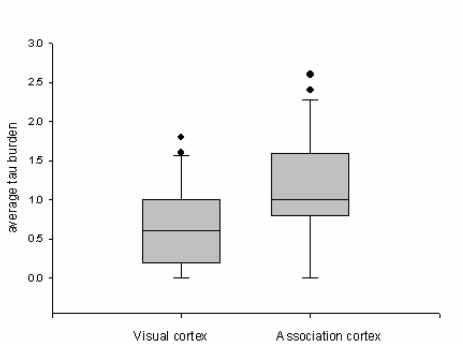

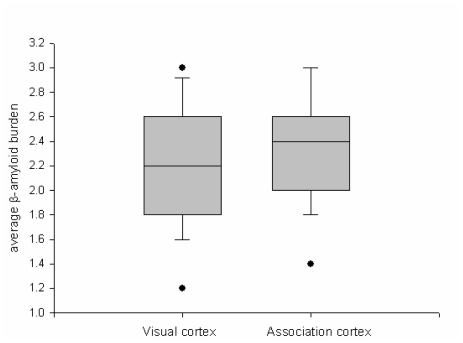

Given that CAA is detected in most AD brains [9, 10], it was not difficult to identify cases suitable for study. All cases had moderate to severe CAA in both parenchymal and leptomeningeal vessels. The severity of CAA differed by region and by individual. Both visual and association cortices were affected in almost every patient. Tau pathology (i.e. NFT and NTs) and perivascular neuritic dystrophy related to CAA was observed in cortical layers II, III and V, and was more severe in the association than visual cortex (Figure 2). The severity of perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy and Aβ deposition was assessed in the two regions. The perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy score differed significantly between visual and association cortices (P=0.003; Figure 3). On the other hand, there was no difference in the perivascular Aβ score between the two cortices (P=0.302; Figure 4). There were positive correlations between the severity of perivascular tau and perivascular Aβ scores for both primary and association cortices (Table 1).

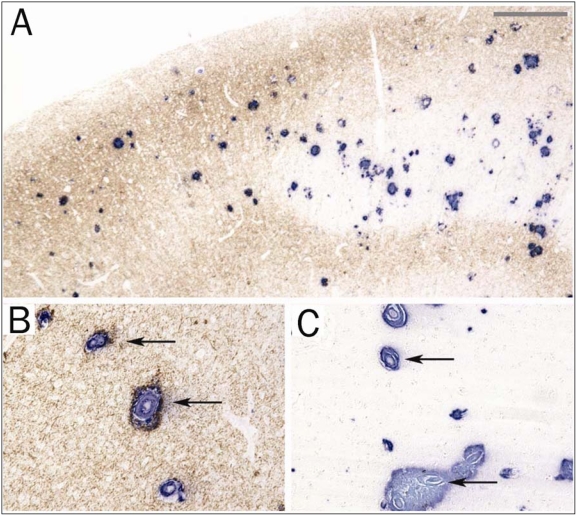

Figure 2.

A low power photomicrograph of the border (A) between the primary visual cortex (right half; area 17) and the association cortex (left half; area 18) of a patient with AD and CAA that has been double immunostained for Aβ (blue) and tau (brown). The left half is rich in tau pathology. (Bar = 188 μm) B. CAA accompanied by perivascular neuritic dystrophy in association cortex. (Bar = 75 μm) C. CAA accompanied by minimal to no perivascular neuritic dystrophy in visual cortex. (Bar = 75 μm).

Figure 3.

Comparison of perivascular neuritic dystrophy related to CAA in visual and association cortices. The boxes show median and 25th and 75th percentiles with whisker plots showing 10th and 90th percentiles. The outliers are shown as filled circles. The average tau burden score is significantly higher in association cortex than in visual cortex.

Figure 4.

Comparison of perivascular Aβ deposition related to CAA in visual and association cortices. The boxes show median and 25th and 75th percentiles with whisker plots showing 10th and 90th percentiles. The outliers are shown as filled circles. The average amyloid burden score is not significant between the two cortices.

Table 1.

Correlations between perivascular neuritic dystrophy and Aβ scores

| Primary visual cortex | Visual association cortex |

|---|---|

| r = 0.245 | r = 0.267 |

| p < 0.01 | p < 0.01 |

Discussion

At present, the widely accepted neuro-pathologic criteria for AD do not include assessment of CAA, let alone perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy associated with CAA [6]. While there have been a few reports addressing the relationship between tau pathology and CAA, there have been no previous studies addressing potential differences in this pathologic feature in primary versus association cortices. In a recent study, McKee and co-workers reported that CAA, SPs and NFTs can be detected in occipital association cortices in cases with absent or sparse medial temporal lobe Alzheimer type pathology, suggesting that occipital association cortices may be particularly vulnerable in preclinical AD [7] and warranting further investigation of occipital pathology. Delacourte and coworkers reported the morphological characteristics and relationships of CAA to tau pathology in AD [1], and Williams and coworkers described perivascular tau neuritic dystrophy associated with CAA [11]. None of these studies specifically addressed the relationship between perivascular Aβ deposition and tau neuritic dystrophy associated with CAA with respect to association and visual cortices.

A result of this study that is worth emphasizing is that perivascular neuritic dystrophy associated with CAA is more severe in association than visual cortices (Figure 3). This suggests that the local neuronal environment determines the severity or nature of the perivascular pathology more than the severity of the intrinsic vascular disease. That the relationship had no bearing on severity of CAA or perivascular Aβ is supported by the fact that there was no difference in the average amount of perivascular Aβ deposition in the two cortices (Figure 4).

In this study, we did not investigate vessels with no Aβ deposition; however, there is a previous report that Aβ severity in CAA is not different between the calcarine cortex and visual association area 19 [7]. If all vessels had been examined, the average amount of Aβ deposition in vessels may not have been different between the two cortices.

The results of the present study suggest that perivascular neuritic dystrophy related to CAA is a neglected feature of AD pathology and that further studies are warranted to determine the clinical significance of this pathology and it usefulness in neuropathologic diagnosis.

The findings support the contention that extracellular Aβ deposition might trigger local tau neuritic dystrophy [12–14]. In favor of this hypothesis is the fact that neuritic dystrophy was correlated with severity of perivascular Aβ deposits. The positive correlation between the severity of perivascular neuritic dystrophy and perivascular Aβ deposition related to CAA in both cortices (Table 1) might support the contention that Aβ deposition related to CAA induces tau pathology. Arguing against this hypothesis is that the same degree of CAA and perivascular Aβ was associated with different severity of tau neuritic dystrophy depending upon the local environment. In the association cortex, a region that is vulnerable to tau pathology, it was considerable, while in the primary cortex, which is less vulnerable to tau pathology, there was less perivascular neuritic dystrophy.

On the other hand, extensive vascular pathology associated with severe CAA may lead to leakage of toxic factors from the blood stream through a disrupted blood brain barrier. Changes in glia (perivascular microglia and astrocytes) associated with CAA and perivascular Aβ deposition may also play a role in perivascular neuritic dystrophy through release of neurotoxic mediators. Further studies looking at these factors may shed light on why dyshoric angiopathy is associated with neuritic dystrophy and why this process varies depending upon the nature of the cortical region in which the dyshoric amyloid angiopathy resides.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Virginia Philips, Linda Rousseau and Monica Castanedes-Casey for their expert technical assistance. We appreciate the gift of antibodies by Todd Golde and Peter Davies. Most of the cases in this study were from the State of Florida Alzheimer Disease Initiative, and the generous donations of family members in this endeavor are greatly appreciated. This study was supported by NIH grants: P50-AG25711, P50-AG16574, P01-AG17216 and P01-AG03949, as well as the State of Florida Alzheimer Disease Initiative.

References

- 1.Delacourte A, Defossez A, Persuy P, Peers MC. Observation of morphological relationships between angiopathic blood vessels and degenerative neurites in Alzheimer's disease. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1987;411:199–204. doi: 10.1007/BF00735024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaere P, Duyckaerts C, Masters C, Beyreuther K, Piette F, Hauw JJ. Large amounts of neocortical beta A4 deposits without neuritic plaques nor tangles in a psychometrically assessed, non-demented person. Neurosci Lett. 1990;116:87–93. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90391-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duyckaerts C, Colle MA, Dessi F, Piette F, Hauw JJ. Progression of Alzheimer histopathological changes. Acta Neurol Belg. 1998;98:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson DW, Crystal HA, Mattiace LA, Masur DM, Blau AD, Davies P, Yen SH, Aronson MK. Identification of normal and pathological aging in prospectively studied nondemented elderly humans. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:179–189. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90027-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attems J. Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: pathology, clinical implications, and possible pathomechanisms. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;110:345–359. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKee AC, Au R, Cabral HJ, Kowall NW, Seshadri S, Kubilus CA, Drake J, Wolf PA. Visual association pathology in preclinical Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:621–630. doi: 10.1097/00005072-200606000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyman BT. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: clinical – pathological studies. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S27–32. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu D, Yang C, Wang L. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in aged Chinese: a clinico-neuropathological study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2003;106:89–91. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0706-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zekry D, Duyckaerts C, Belmin J, Geoffre C, Moulias R, Hauw JJ. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the elderly: vessel walls changes and relationship with dementia. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2003;106:367–373. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams S, Chalmers K, Wilcock GK, Love S. Relationship of neurofibrillary pathology to cerebral amyloid angiopathy in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2005;31:414–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2005.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, Chisholm L, Corral A, Jones G, Yen SH, Sahara N, Skipper L, Yager D, Eckman C, Hardy J, Hutton M, McGowan E. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293:1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oddo S, Billings L, Kesslak JP, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Abeta immunotherapy leads to clearance of early, but not late, hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates via the proteasome. Neuron. 2004;43:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]