Abstract

Nothing is known about the regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in hair cells of the inner ear. MuSK, rapsyn and RIC-3 are accessory molecules associated with muscle and brain nAChR function. We demonstrate that these accessory molecules are expressed in the inner ear raising the possibility of a muscle-like mechanism for clustering and assembly of nAChRs in hair cells. We focused our investigations on rapsyn and RIC-3. Rapsyn interacts with the cytoplasmic loop of nAChR α9 subunits but not nAChR α10 subunits. Although rapsyn and RIC-3 increase nAChR α9 expression, rapsyn plays a greater role in receptor clustering while RIC-3 is important for acetylcholine-induced calcium responses. Our data suggest that RIC-3 facilitates receptor function, while rapsyn enhances receptor clustering at the cell surface.

Keywords: Peripheral auditory system, synaptogenesis, cholinergic synapse, receptor assembly and clustering

Introduction

The neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) that bind α-bungarotoxin (α-Bgtx) are somewhat unique in that they can be functionally expressed as homomeric receptors and have high calcium permeability (Boulter et al., 1987; Deneris et al., 1988; Wada et al., 1988; Elgoyhen et al., 1994; Seguela et al., 1993; Lindstrom et al., 1998). The inner ear has neuronal nAChRs that mediate cholinergic synaptic transmission and play crucial physiologic roles (Elgoyhen et al., 1994; Elgoyhen et al., 2001; Katz et al., 2004; Kujawa et al., 1992, 1994; Maison et al., 2002; Sgard et al., 2002; Simmons, 2002). In the cochlea, outer hair cells (OHCs) have neuronal nAChRs composed of α9 and α10 subunits (Lustig, 2006). As compared to expressed homomeric α9 receptors, the heteromeric α9α10 receptors have larger calcium responses and a pharmacology that closely matches isolated OHC responses (Elgoyhen et al., 2001). In adult animals, OHCs are directly innervated by cholinergic axons that form the descending arm of a sound evoked reflex pathway (Simmons, 2002). During development, a transient cholinergic innervation of inner hair cells (IHCs) has been proposed (Simmons et al., 1998; Simmons et al., 1996). That IHCs at least transiently express both nAChR α9 and nAChR α10 subunits and respond to acetylcholine similar to OHCs corroborates the idea of a transient cholinergic innervation of IHCs during synaptogenesis (Glowatzki and Fuchs, 2000; Gomez-Casati et al., 2005). These studies and others suggest that IHCs and OHCs may assemble and cluster nAChRs during efferent synaptogenesis in the inner ear. However, the molecules associated with nAChR assembly and clustering in hair cells have not been investigated.

To date, the cholinergic mechanisms that induce synapse formation and regulate the differentiation of synaptic specializations have been extensively investigated at the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The earliest AChR clusters in muscle apparently require no nerve-derived signals (Willmann and Fuhrer, 2002). As development proceeds, muscle specific receptor tyrosine kinase (MuSK) and rapsyn (receptor-associated protein of the synapse) are essential for clustering and localization of nAChRs at the developing NMJ (Apel et al., 1997; Lin et al., 2001; Sanes et al., 1998). The 43-kDa peripheral membrane protein rapsyn was isolated by virtue of its tight association with the AChR (Colledge and Froehner, 1998; Gautam et al., 1999). Studies using rapsyn fragments and mutations, expressed in HEK293T cells along with muscle nAChRs, have established that the rapsyn coiled-coiled domain is necessary for nAChR clustering (Bartoli et al., 2001; Ramarao et al., 2001). That rapsyn-AChR aggregates are necessary for AChR clustering in muscle as is also clearly demonstrated by mutant mice lacking rapsyn, which show severe neuromuscular dysfunction with no detectable nAChR clusters on the muscle fiber (Gautam et al., 1999). Furthermore, rapsyn deficiencies affect the formation of nAChR aggregates, can lead to a reduction in the density of synaptic nAChRs (Eckler et al., 2005; Fuhrer et al., 1999) and may be associated with human diseases such as congenital myasthenic syndrome (Ohno et al., 2002; Ohno et al., 2003; Ono et al., 2001). Although it is not known whether rapsyn interacts with the nAChRs in hair cells or induces clustering of these receptors at the cell surface, it is worthwhile to note that myasthenic gravis patients have reduced auditory function, which is reversed after administration of a cholinesterase inhibitor (Paludetti et al., 2001).

In addition to rapsyn and MuSK, other accessory molecules are also necessary for proper assembly, folding, and recruitment of nAChRs to the NMJ. Recent studies have identified a transmembrane protein (RIC-3), which is located within the endoplasmic reticulum and may chaperone nicotinic and serotonergic receptors (Cheng et al., 2007; Halevi et al., 2002; Halevi et al., 2003). Studies in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells demonstrate that co-expression of the human homologue (hRIC-3) can enhance functional expression of α7 nAChRs (Williams et al., 2005). Given the fact that α7 and α9 nAChR subunits share high sequence homology, it is reasonable to infer that RIC-3 may influence the function of the neuronal nAChR subunits in muscle and hair cells respectively. Although α9 and α10 subunits are able to co-assemble and form functional nicotinic receptors when co-expressed in oocytes, efficient cell surface expression of nAChR α9 and nAChR α10 subunits has been difficult in cultured mammalian cells (Baker et al., 2004). Therefore, we speculate that the problems associated with heterologous expression of nAChRs α9α10 in different mammalian cell lines may be circumvented by co-expression of accessory proteins such as rapsyn and RIC-3 proteins.

Although neuronal and muscle nAChR subunits are similar in amino acid sequence (Lindstrom et al., 1998), the role of muscle nAChR accessory proteins at non-muscle nAChR synapses remains elusive (Feng et al., 1998; Missias et al., 1997). Our objective was to investigate whether the molecules associated with nAChR assembly and clustering at the NMJ and other nicotinic synapses are used by hair cells in the inner ear. First, we determine whether nAChR clustering and assembly molecules are expressed in the inner ear. Second, we examine whether nicotinic clustering and assembly molecules interact with α9 containing nAChRs. Third, we investigate the effects of nicotinic clustering and assembly molecules on the heterologous expression of nAChRs α9α10 in cultured mammalian cell lines. Finally, we investigate whether clustering and assembly molecules facilitate calcium responses in nAChR α9α10 transfected cells. Our data provide evidence that molecules associated with nAChR clustering and assembly at muscle and central synapses may be used by hair cells in the inner ear.

Results

Endogenous expression of nAChR accessory proteins during development

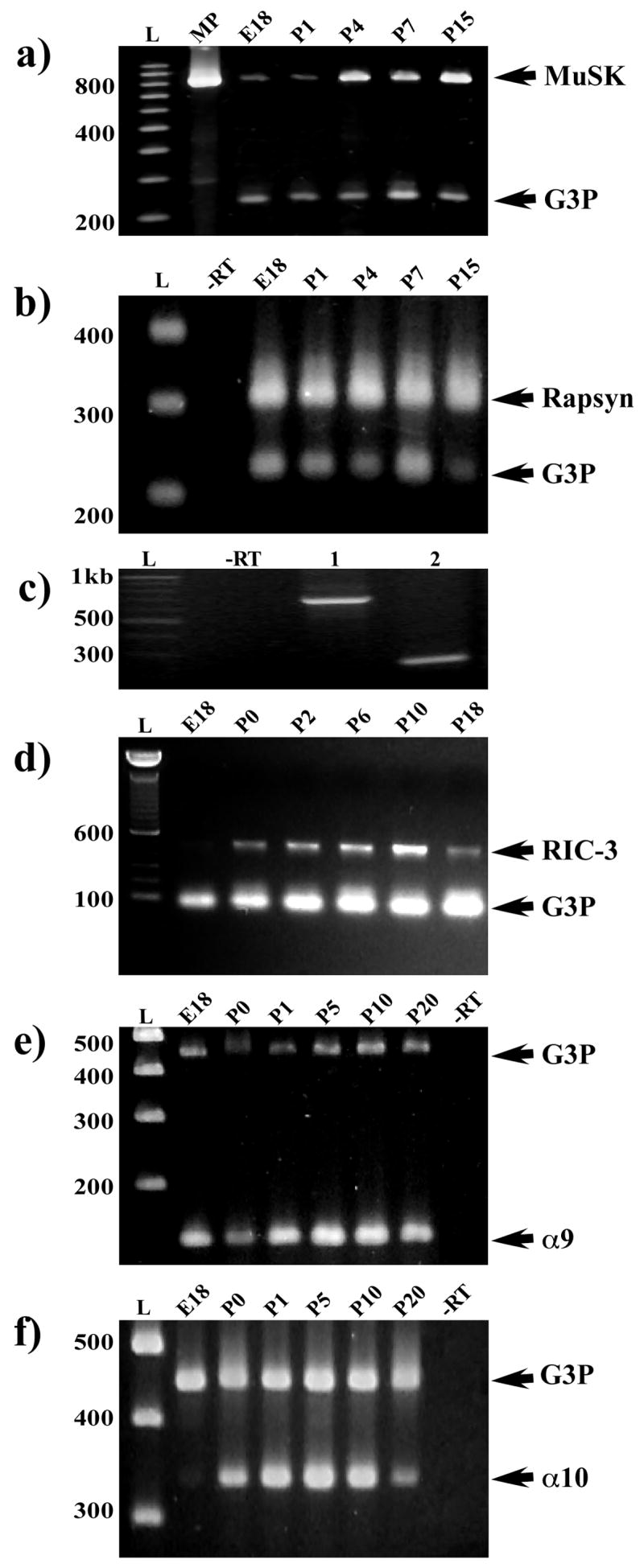

The inner ear expresses several nAChR accessory molecules also found at the NMJ. Specifically, we have identified MuSK, rapsyn and RIC-3 within inner ear tissues. RT-PCR primers generated against MuSK mRNA amplify transcripts weakly at E18 but show stronger amplification in older tissues (Fig. 1a). Partial amino acid sequence analysis based on amplified nucleotide sequences indicates that cochlear MuSK contains at least four intracellular kinase domains that are important in MuSK signaling (Fu et al., 1999).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression of α9, α10, rapsyn, RIC-3, and MuSK using RT-PCR in developing cochlear tissues. (a) Semi-quantitative analysis of cochlear MuSK expression relative to a gene reporter control (glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, G3P). The 829 bp amplicon was generated from gene-specific primers using rat MuSK mRNA sequence (U34895) and contains four of eleven intracellular kinase domains important for MuSK signaling (Fu et al., 1999). The highest levels of MuSK expression occur after P1. MuSK is expressed weakly at E18 and P1. MP = PCR product generated from a cloned insert of an 829 bp amplicon. (b) Semi-quantitative analysis of cochlear rapsyn mRNA expression compared to a gene reporter control (glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, G3P). The 303 bp amplicon of rapsyn is expressed at the same relative level throughout the first two weeks of postnatal development. Gene-specific primers were designed using the mouse rapsyn mRNA sequence (NM009023), specifically, a portion containing three of seven potential tetratricopeptide repeats. The RT-PCR includes a –RT control lane. (c) Expression of rapsyn mRNA is seen within isolated OHCs from the apical turn of two-week old rat cochleae. RT-PCR results show a 680 bp and a 222 bp fragment from different regions of the rapsyn rat sequence were amplified from OHC mRNA. (d) A duplex PCR demonstrates that RIC-3 transcripts are developmentally regulated in the mouse ear. A primer pair based on partial rat RIC-3 sequence (GenBankTM accession number XM_219241) was designed to amplify a unique 422 bp PCR fragment contained within the coiled-coil domain. The PCR product detected indicates the presence of RIC-3 transcripts in postnatal mouse cochleae. A 104 bp primer set to glyceraldehyde- 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3P, Clontech) was used as a house keeping gene. RIC-3 mRNA was expressed at a relatively low level at E18. The highest levels of RIC-3 expression occurred between P0 and P10 during development. The RT-PCR includes a –RT control lane. (e, f) nAChRα9 and α10 primers were designed against nonoverlapping regions of their cDNA sequences. Primers were designed to amplify a 122-bp fragment of nAChR α9 subunit sequence (GenBank Accession number NM_022930) and a 344-bp fragment of α10 acetylcholine receptor subunit sequence (GenBank Accession number NM_022639). A 450-bp fragment of G3P (Clontech) was used in amplification reactions as an internal control. nAChR α9 was detected in the cochlea at E18 and all subsequent ages. Expression of nAChR α10 mRNA was detected at E21 and all subsequent ages. The RT-PCR includes a –RT control lane.

Rapsyn mRNA is expressed at the same relative level from E18 through P7 and has higher expression levels at later postnatal ages (Fig. 1b). The rapsyn amplified PCR sequence contains three tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs) that have been implicated in the ability of rapsyn to co-cluster other molecules (Ramarao et al., 2001). Rat cochlear rapsyn TPRs show amino acid sequence identity to the published mouse sequence (data not shown). Since efferent fibers make synapses directly on outer hair cells (OHCs) in older postnatal animals (see review by Simmons, 2002), rapsyn should be expressed specifically in OHCs. Different regions of rapsyn sequence were amplified in isolated OHCs (Fig. 1c) demonstrating that rapsyn is specifically expressed in hair cells.

For RIC-3 mRNA expression, primers based on mouse RIC-3 sequence amplify a unique PCR fragment contained within the transmembrane region that is essential for mediating interactions with nAChR subunits (Ben-Ami et al., 2005). In Figure 1d, RIC-3 is expressed at relatively low levels at E18, higher levels between P0 and P10, and significantly reduced levels beginning at P18 levels.

PCR amplicons were generated for nAChR α9 and nAChR α10 mRNA sequences. Similar to previous reports (Morley and Simmons, 2002), nAChR α9 mRNA is detected in the cochlea at E18 and remains elevated during all subsequent ages (Fig. 1e). On the other hand, nAChR α10 expression starts at E21 and has peak expression at P5 and P10 (Fig. 1f). MUSK, rapsyn and nAChR α9 are present at relatively high levels at E18 whereas RIC-3 and nAChR α10 expression may be more delayed. Taken together, our results demonstrate that molecules involved in nAChR assembly and clustering at the NMJ are present in rodent inner ear and correlate with nAChR subunit expression during development.

Interaction of nAChR subunits with rapsyn and RIC-3

Previous studies have shown that the coiled-coil domain (CCD) of muscle rapsyn mediates nAChR clustering and specifically interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of the β-subunit of the muscle nAChR (Ramarao and Cohen, 1998). How rapsyn interacts with neuronal nAChR α subunits and whether it interacts preferentially with one α subunit or equally with both subunits is unknown. The differential regulation of nAChR α9 and α10 subunits as suggested from our RT-PCR studies, might suggest differences in their interactions with clustering molecules. We hypothesized that clustering interactions may occur predominately through the intracellular domain of the α10 subunit since it has a later onset, more of a facilitatory role, and is not essential for α9 receptor function (Morley and Simmons, 2002; Sgard et al., 2002). We examined whether the rapsyn-CCD binds to nAChR α9 or α10 subunits using a yeast two-hybrid analysis. The rapsyn-CCD was amplified by PCR from whole rat cochlea (cRAP1) or muscle (pSOS2) and subcloned into a yeast two-hybrid binding domain (BD) vector, while the intracellular domains (ICDs) of either nAChR α9 or α10 were subcloned into the activation domain (AD) vector. Only theα9-ICD shows significant interaction with either muscle or cochlear rapsyn, while α10-ICD shows little evidence of interaction with either rapsyn (Table 1). This result suggests that the nAChR α9 subunit may be more important than nAChR α10 in any rapsyn-mediated clustering. Amino acid sequence alignment of the intracellular domain of nAChR α9 and α10 subunits shows a high degree of variability (Lustig, 2006). Such variation in sequence homology may account for the differential selectivity of rapsyn-CCD to associate with the nAChR subunits. Protein-protein interaction between nAChR α9 and rapsyn was further confirmed by in vitro co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), and by switching AD and BD vector inserts. An α9-ICD fragment fused to c-Myc and a rapsyn fused to HA tagged proteins were constructed. As shown in Figure 2a (lanes 7 and 8), labeling of α9-ICD and rapsynCCD confirms interaction of α9 with rapsyn in vitro. These results were further authenticated by Western blot (data not shown).

Table 1.

In this yeast two-hybrid experiment, two different rapsyn-coiled coil domain (CCD) constructs were tested: from muscle (pSOS2) and cochlea (cRAP1). The yeast line AH109 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was co-transfected with pGADt7-Rapsyn-CCD and either pGBKT7-α9 or pGBKT7-α10 using the LiAC technique. Growth on SD-Leu verifies transfection of the pGAD-rapsyn plasmid into yeast. Growth on SD-Trp verifies transfection of the pGBK plasmid containing the intracellular loop of either nAChR α9 or α10. Growth on SD-HLT (media lacking histidine, leucine, tryptophan) and growth on SD-AHLT+X-α–gal selects for those yeast containing not only both plasmids, but verifies protein binding between rapsyn-CCD and the nicotinic receptor intracellular loop. Interestingly, only the intracellular portion of nAChR α9 shows binding to Rapsyn, while α10 shows no evidence of interaction with rapsyn.

| Plasmids | SD minimal Medium and Growth Phenotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapsyn | Yeast Two-Hybrid | SD-Leu | SD-Trp | SD-Leu-Trp | SD-HLT | SD-AHLT-Xαgal |

| cRAP1 | α9/pGBK | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| cRAP1 | α10/pGBK | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - |

| pSOS2 | α9/pGBK | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| pSOS2 | α10/pGBK | +++ | +++ | +++ | - | - |

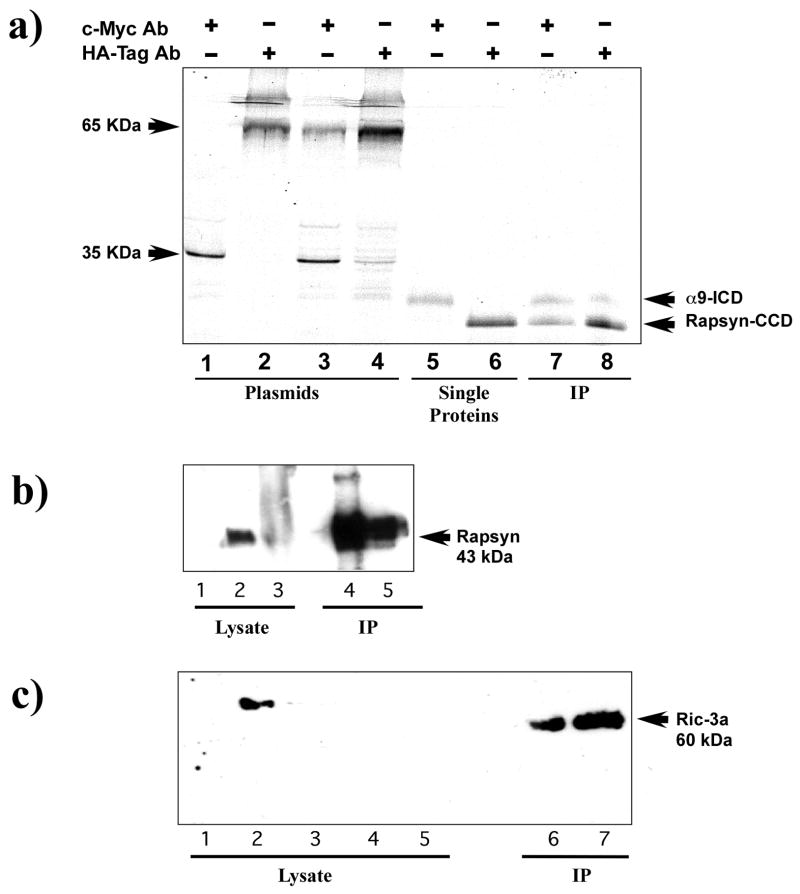

Figure 2.

Immunopreciptitation of nAChR α9 subunit interactions with rapsyn and RIC-3. (a) An autoradiograph of in vitro expression of S35 methionine labeled proteins of the intracellular domain of the nAChR α9 subunit (α9-ICD) and the coiled-coil domain of rapsyn (rapsyn-CCD). Lanes 1–4 contain internal positive controls of murine p53 (c-Myc epitope) and SV40 large T-antigen (HA epitope) that were used in the for the yeast two-hybrid screen. They show that precipitation of either the murine p53 or the large T-antigen results in a single band (lanes 1 and 2) while immunoprecipitation of murine p53 mixed with large T-antigen results in two bands (lanes 3 and 4). Similarly, lanes 5 and 6 show that the nAChR α9-ICD labeled with the c-Myc epitope is recognized by the c-Myc antibody and rapsyn-CCD labeled with the HA epipitope is recognized by the HA antibody. Lanes 7 and 8 are experimental co-immunoprecipitation lanes. The c-Myc antibody (lane 7) precipitated labeling of both α9-ICD and rapsyn-CCD. Similarly, in lane 8 the HA antibody precipitated labeling of both α9-ICD and rapsyn-CCD fragments. The authenticity of the rapsyn-HA and α9-myc fragments were confirmed by Western blot. (b) Immunoblot analysis of the expression of full-length nAChRα9 subunit and rapsyn in HEK293T cells and mouse cochlea homogenates. nAChR α9 subunit was immunoprecipated with α9 antibody and immunoblots then probed with rapsyn antibody. A specific band corresponding to the 43-kDa mouse rapsyn was detected in α9 and rapsyn co-transfected HEK293T cells (lane 4) and observed in lysate obtained from mouse cochleae (lane 5). Positive controls from HEK293T cells transfected with rapsyn alone (lane 1), mouse muscle (lane 2) and cochlea (lane 3) were used. (c) Immunoprecipitation (IP) of nAChR α9 subunit followed by immunoblot analysis with RIC-3a antibody. As shown: lane 1 (HEK293T cells untransfected), lane 2 (HEK293T cells transfected with RIC-3 cDNA), lane 3 (QT-6 cells untransfected), lanes 4 and 5 (mouse and rat cochlea lysates, respectively). HEK392 cells co-transfected with AChRα9 subunit and RIC-3 cDNAs and then immunoprecipitated with AChRα9 antibody (lane 7), show a band of ~ 60 kDa, consistent with the RIC-3 expected molecular size. A similar band was also observed from rat cochlea that was immunoprecipitated AChRα9 antibody (lane 6).

To determine whether interactions with α9 containing nAChRs are possible within mammalian cells and tissues, we performed Co-IP experiments on lysates from HEK293T cells co-transfected with full-length of human α9 (hα9) and mouse (m)-rapsyn cDNAs, and lysates from mouse cochleae (Fig. 2b). We found a specific band corresponding to m-rapsyn (43-kDa) is detected in transfected HEK293T cells and mouse cochleae. As expected, a very distinct band of rapsyn was observed with the muscle lysate compared to the cochlear lysate because muscle cells are known to express high levels of rapsyn (Moransard et al., 2003). Overall, these results demonstrate that nAChR α9 and rapsyn are able to interact directly and perhaps co-assemble both in in vitro expression systems as well as in the rodent cochlea.

RIC-3 has already been shown to interact with nAChR α7 in heterologous expression systems but its interaction with neuronal receptors in mammalian tissues has not been studied. We also performed Co-IP experiments between nAChRα9 and RIC-3 (Fig. 2c) using lysates from HEK293T cells co-expressing nAChR α9 and RIC-3 and from rat cochlea. When these heterologous and cochlear lysates were immunoprecipitated with nAChRα9 antisera and the immunoblots probed with RIC-3 antisera (RIC-3a), they showed similar size bands of approximately 60 kDa corresponding to the known size of RIC-3. Our results suggest that the nAChR α9 subunit and RIC-3 co-associate in HEK293T cells and in vivo in rodent cochlear tissues. This direct interaction may be necessary for forming a stable complex and enhancing proper folding and/or assembly of the α9 containing nAChR.

Rapsyn and RIC-3 localization and α-bungarotoxin labeling

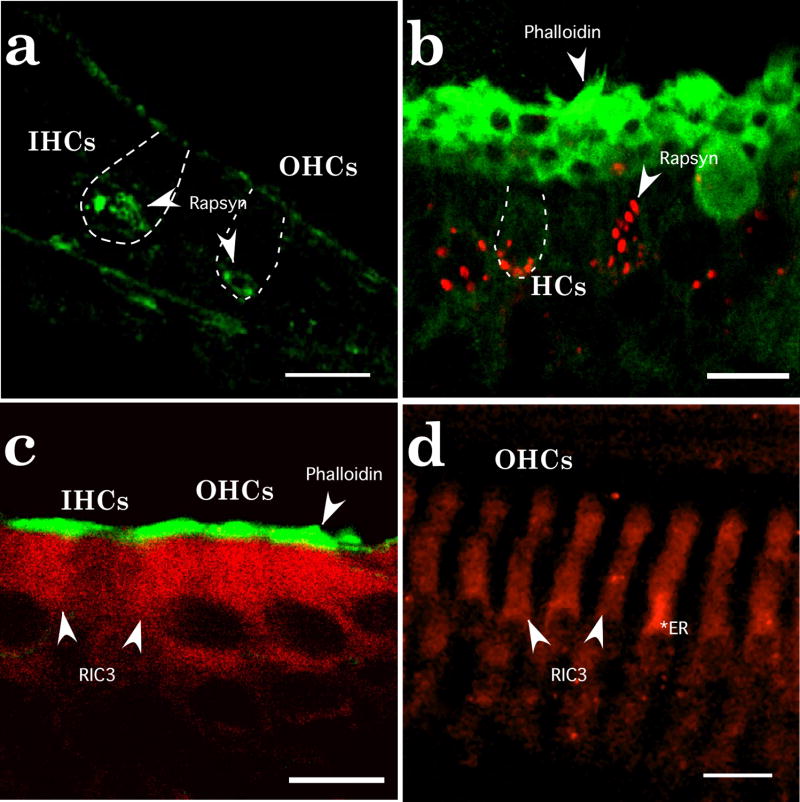

The localization of rapsyn and RIC-3 in inner ear tissues was confirmed with immunofluorescent staining. Rapsyn and RIC-3 immunoreactivities were most intense in sensory hair cells in both auditory and vestibular organs (Fig. 3). At birth, rapsyn immunoreactivity is concentrated at the neural poles of hair cells and becomes more punctate and distinctive at older postnatal ages (Fig. 3a,b). Rapsyn also demonstrates a weak immunoreactive signal in supporting cells. In older ages, rapsyn immunoreactivity in IHCs becomes indistinguishable from background levels (data not shown). Unlike rapsyn immunoreactivity, RIC-3 immunoreactivity is diffusely expressed throughout hair cells at both newborn and older postnatal ages (Fig. 3c,d). RIC-3 preferentially labels OHCs by P10. We also noticed a preferential perinuclear labeling of RIC-3 immunoreactivity within OHCs at older postnatal ages consistent with its putative role as an ER chaperone protein. Supporting cells, especially Dieters’ cells in the cochlea, show RIC-3 immunoreactivity just above background levels. These data indicate that rapsyn and RIC-3 localize preferentially to sensory hair cells in the inner ear.

Figure 3.

Localization of rapsyn and RIC-3 immunoreactivity in rat inner ear. (a) In the P1 cochlea, rapsyn immunoreactivity (green, as indicated by arrows) is seen most intense near the basal pole of hair cells. Rapsyn immunoreactivity is found in inner hair cells (IHCs) and in outer hair cells (OHCs) although less intense. (b) In the P10 sacculus, rapsyn (red, arrows) formed plaque-like structures that surrounded the basal pole of hair cells. At least in saccular hair cells, rapsyn immunoreactivity could extend above the nucleus. Hair bundles are labeled by phalloidin (green). (c) In the P1 cochlea, RIC-3 immunoreactivity (red) diffusely (arrows) labeled IHCs and OHCs. Supporting cells, especially Deiters’ cells below the OHCs and pillar cells between inner and outer hair cells, showed RIC-3 staining slightly above background tissue levels. Hair bundles were labeled with phalloidin (green). (d) In the P10 cochlea, RIC-3 immunoreactivity (red) is found in OHCs (arrows). The asterisk indicates intense staining levels within the cytoplasm and above the nucleus. Supporting cells and IHCs had RIC-3 staining near background levels. Scale bars in a–c represent 10 μm and the scale bar in d represents 15 μm.

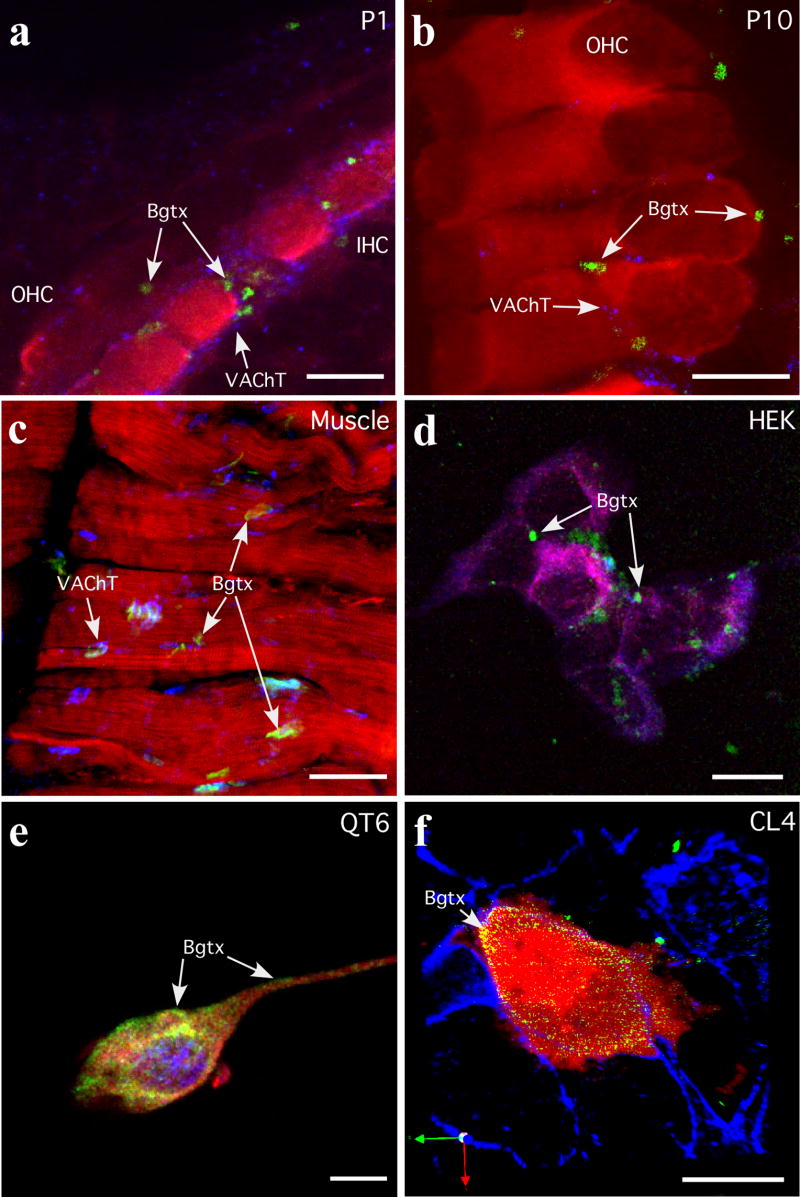

Having demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo interactions of rapsyn and RIC-3 with the nAChR α9 subunit (see Fig. 2), we set out to determine if either rapsyn or RIC-3 can enhance the expression of α9 containing nAChRs at the cell surface. α-Bungarotoxin (α-Bgtx) binds with high affinity to the extracellular portion of the α-subunit of muscle and neuronal nAChRs and commonly indicates a degree of functionality (Arias, 2000; Clarke, 1992). Since it has been difficult to demonstrate reliably α-Bgtx-labeling on sensory hair cells (Canlon et al., 1989; Ishiyama et al., 1995), we first investigated α-Bgtx labeling of nAChRs in freshly isolated cochlear hair cells from postnatal day P1 and P10 rat pups. As shown in Figure 4, cochleae at P1 and P10 demonstrate vital α-Bgtx labeling as distinct plaque-like structures restricted almost exclusively to hair cells. As previously described for efferent innervation (Simmons, 2002), α-Bgtx labeling follows a similar developmental progression: it is first seen mostly on IHCs at P1 and then becomes progressively localized to OHCs by P10. Although α-Bgtx labeling exhibited the same spatial development as efferent innervation at P1, double labeling with a cholinergic terminal marker (vesicular acetylcholine transferase, VAChT) reveals that there are numerous cholinergic terminals not associated with α-Bgtx labeled puncta (Fig. 4a). However, by P10, the amount of VAChT immunoreactive terminals is reduced on OHCs and α-Bgtx-labeling overlaps extensively with efferent terminals on OHCs. Although these results are in agreement with the general progression of efferent innervation and α9α10 nAChR subunit expression, they also suggest that the initial appearance of α-Bgtx-labeling may be independent of efferent innervation. In agreement with published results, α-Bgtx labeling of muscle nAChRs was observed under the same labeling conditions for hair cells at the NMJ (Fig. 4c) (Clarke, 1992; Frank and Fischbach, 1979). The α-Bgtx labeled clusters at the NMJ were two to three times larger than those on hair cells.

Figure 4.

α-Bungarotoxin (α-Bgtx) labeling of nAChR α9 and α10 in cochlear tissues and cultured cells. (a, b) Cochlear hair cells from P1 and P10 rat pups were labeled with α-Bgtx (488 nm, green), an immunocytochemical hair cell marker, either α-parvalbumin or myosin VI (546 nm, red), and an efferent terminal marker (vesicle acetylcholine transferase, VAChT; 647nm, blue). Arrows identify α-Bgtx labeled clusters. (c) Muscle was used as a labeling control. Shown is muscle diaphragm labeled with α-Bgtx (488 nm, green), phalloidin and myosin VI (546 nm, red), and vesicle acetylcholine transferase (VAChT; 647nm, blue). Arrows identify α-Bgtx labeled neuromuscular junctions. (d) HEK293T cells transfected with nAChR α9, rapsyn and RIC-3 cDNAs were labeled with α-Bgtx (488 nm, green), then processed for immunofluorescence with anti-α9 (594 nm, red), anti-RIC-3 (647 nm, blue). Arrows identify α-Bgtx labeled clusters. (e) QT6 cells transfected with nAChR α9, nAChR α10, and rapsyn cDNAs were labeled with α-Bgtx (488 nm, green), then processed for immunofluorescence with anti-α9 (594 nm, red), anti-rapsyn (647 nm, blue). Arrows identify α-Bgtx labeled regions at the cell surface. (f) CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9, nAChR α10, rapsyn, and RIC-3 cDNAs were labeled with α-Bgtx (488 nm, green) and then processed for immunofluorescence with anti-GFP (594 nm, red) and phalloidin (647 nm, blue). Arrows identify α-Bgtx labeled regions at the cell surface. The CL4 cell line does not express endogenous α9, α10, rapsyn or RIC-3 as determined by PCR (data not shown), and therefore is a suitable host cell type in which to express functional recombinant α9α10 nAChRs. Scale bars in a,- c frepresent 10 μm and scale bars in d–f represent 20 μm.

To assess the roles of rapsyn and RIC-3 in enhancing α-Bgtx labeling, we examined α-Bgtx labeling in HEK293T, QT6 and CL4 (LLC-PK1)cell lines transiently transfected with various combinations of nAChR α9 and α10, rapsyn and RIC-3 cDNAs (Fig. 4c, d, e). In HEK293T and QT6 transfected cells, α-Bgtx labeling overlaps extensively with nAChR α9 immunoreactivity at the cell surface. It is also clear in HEK293T and QT6 cells that nAChR α9 immunoreactivity mostly overlaps with RIC-3 and rapsyn immunoreactivities supporting the idea that nAChRα9 associates with both RIC-3 and rapsyn. In Figure 4c, the purple color demonstrates very nicely the extensive overlap of anti-α9 (red) and anti-RIC-3 (blue). This overlap between nAChRα9 and RIC-3 is mostly intracellular but may also extend to the cell surface. However, there is little evidence of any overlap between α-Bgtx (green) and RIC-3 (blue). In Figure 4d, the arrows identify green (Bgtx) label. There is some labeling of both nAChR α9 (red) and rapsyn (blue) in or over the nucleus of the OT6 cell shown. This labeling was typical of our QT6 cells co-transfected with nAChR α9α10 and rapsyn. Using RT-PCR amplification, HEK293T cells did not express endogenous nAChR α9 and α10, rapsyn or RIC-3, however, QT6 cells did express endogenous RIC-3 but not α9,α10, or rapsyn (data not shown).

To circumvent some of the disadvantages of having to use immunocytochemistry retrospectively to identify and analyze cells transfected with nAChR subunits, CL4 cells were transiently transfected with nAChR α9 and α10 constructs containing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as well as rapsyn and RIC-3. In addition to being larger than HEK293T cells, CL4 cells are derived from a brush border epithelial cell expressing cell line and are used extensively for studies of protein targeting and calcium dynamics (Hensley and Mircheff, 1994; Tyska and Mooseker, 2002). α-Bgtx binding to transfected CL4 cells is mostly restricted to the peripheral edges of the cell surface (Fig. 4e). The pattern of α-Bgtx binding and α9/α10 labeling suggests that the nAChRs in these transfected cells are capable of translocating to the plasma membrane and binding α-Bgtx.

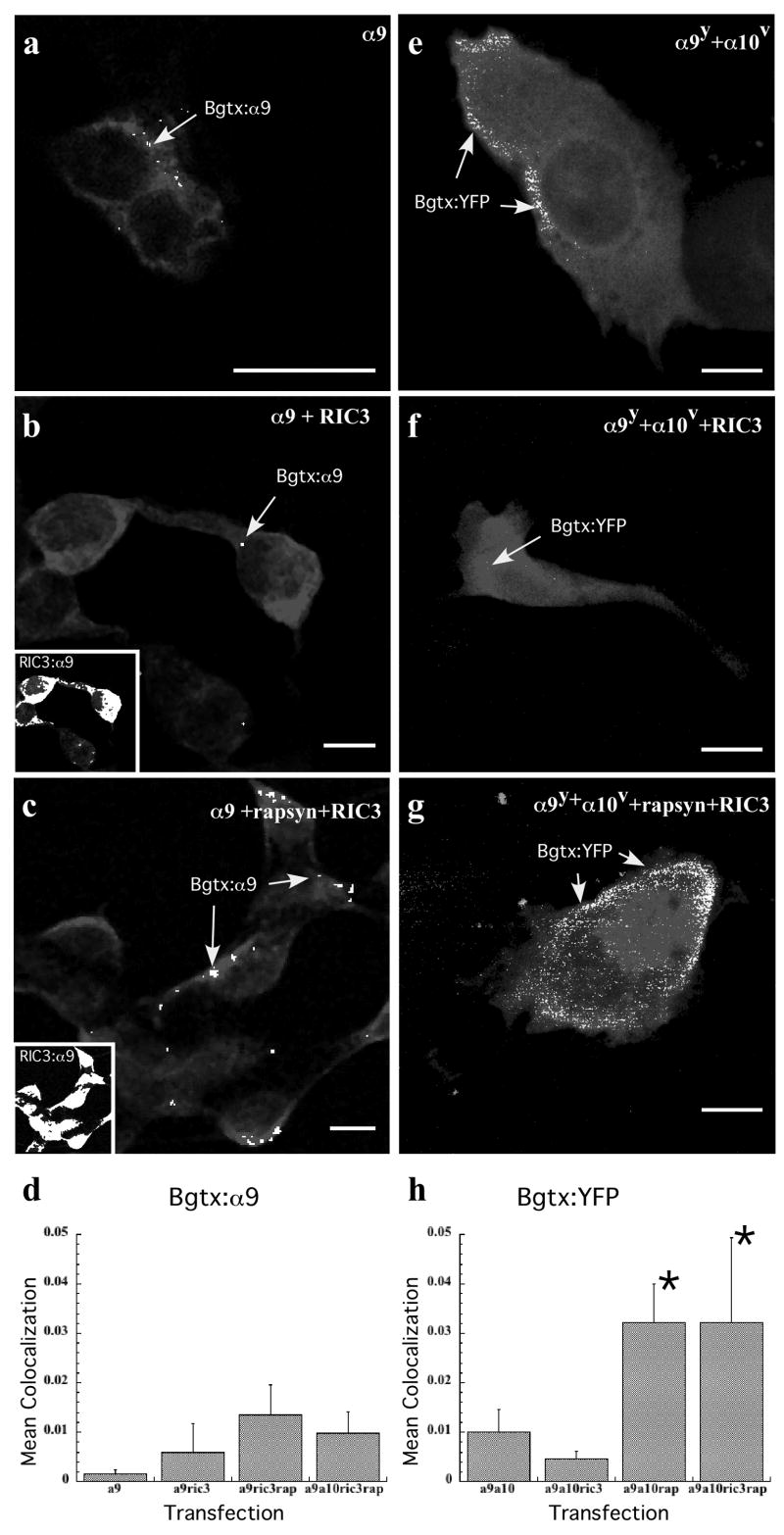

Heterologous expression and surface expression of nAChRs

Given the apparent association of rapsyn and RIC-3 with the nAChR α9 subunit as suggested by the data presented above (Figs. 2 and 4), we tested whether these accessory proteins can enhance nAChR clustering at the plasma membrane in transiently transfected mammalian cell lines. We also specifically address colocalization and not just overlap between α-Bgtx and nAChRα9 as well as between Ric3 and nAChRα9. Although the successful functional heterologous expression of α9 containing nAChRs has been reported in frog oocytes, it has been difficult to express α9 containing nAChRs in mammalian cell lines (Baker et al., 2004; Lansdell et al., 2005; Nie et al., 2004). Using HEK293T cells, we specifically wanted to address interactions with α9 homomeric receptors. No α-Bgtx labeling was found in HEK293T cells that lacked nAChR α9 or α10 transfection. HEK293T cells transfected only with nAChR α9 demonstrated weak α-Bgtx labeling (Fig. 5a). Transfecting HEK293T cells with nAChR α9 and RIC-3 gave highly variable results including sometimes producing only minimal α-Bgtx labeling (Fig. 5b). The addition of α10 did not change the level of α-Bgtx labeling, however, the addition of rapsyn along with nAChRα9 and RIC-3 made a large difference in the level of α-Bgtx labeling (Fig. 5c). Consistent with the idea that RIC-3 and nAChR α9 interact, we found the colocalization between RIC-3 and nAChR α9 is quite extensive and independent of the presence of rapsyn (Fig. 5b and 5c, insets). Although not shown, the colocalization of rapsyn with nAChR α9 was also quite extensive. The pattern of α-Bgtx and nAChR α9 labeling additionally suggests that some α9 receptor subunits are capable of translocating to the plasma membrane and most likely forming homomeric receptors. Figure 5d shows the colocalization coefficients for nAChR α9 immunoreactivity and α-Bgtx labeling. Colocalization coefficients for HEK293T cells transfected with nAChR α9, RIC-3 and rapsyn were nearly 10 times greater than the colocalization coefficients for cells transfected with nAChR α9 alone. These experiments in HEK293T cells indicate that rapsyn co-expression plays a role enhancing α-Bgtx binding to α9 receptors. These data also suggest that the addition of nAChR α10 subunits or RIC-3 does not significantly improve α-Bgtx binding in HEK293T cells (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Colocalization of AChR subunits and α-Bgtx in transfected HEK293T (a–d) and CL4 (e–h) cells. (a) HEK293T cells transfected only with nAChR α9 cDNA demonstrated some α-Bgtx labeling. nAChR α9 immunoreactivity (gray) is seen throughout the cytoplasm and concentrated along the cell surface. The arrow identifies regions (white) where α-Bgtx labeling co-localizes with nAChR α9 immunoreactivity on the cell surface. (b) α-Bgtx labeling of HEK293T cells transfected with nAChR α9 and RIC-3 cDNAs. The arrow identifies regions (white) where α-Bgtx labeling co-localizes with nAChR α9 immunoreactivity on the cell surface. The inset shows extensive areas of co-localization (white) between RIC-3 and nAChR α9 immunoreactivities. (c) α-Bgtx labeling of HEK293T cells transfected with nAChR α9, rapsyn and RIC-3 cDNAs. Note that the α-Bgtx labeling is substantially higher than either panels a or b. The inset shows extensive areas of co-localization (white) between RIC-3 and nAChR α9 immunoreactivities. (d) Graph of the mean co-localization coefficient (Mx) of α-Bgtx labeling with nAChR α9 in HEK293T cells. Calculating the Manders’ colocalization coefficient (Mx) (Manders et al., 1993) gives the fraction of colocalizing objects in each voxel component of a dual color image. The graph shows the mean fraction of nAChR α9 labeled voxels that also contain α-Bgtx labeling. (e) CL4 cells transfected with α9 and α10 cDNAs fused with YFP and Venus tags respectively show some α-Bgtx labeling concentrated along the periphery. The arrows show regions (white) where α-Bgtx labeling co-localizes with GFP immunoreactivity on the cell surface. (f) α-Bgtx labeling in CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9, α10 and RIC-3. The arrow shows regions (white) where α-Bgtx labeling co-localizes with GFP immunoreactivity. (g) α-Bgtx labeling of nAChR α9 and α10 subunits transfected simultaneously with Rapsyn and RIC-3 in CL4 cells. Note that the α-Bgtx labeling is increased in the presence of rapsyn. The arrows show regions (white) where α-Bgtx labeling co-localizes with GFP immunoreactivity on the cell surface. (h) Graph of the mean co-localization coefficient of α-Bgtx labeling with GFP immunoreactivity in transfected CL4 cells. The co-localization coefficient (Mx) represents the fraction of YFP labeled voxels that are co-labeled with α-Bgtx. Scale bars in a–c and e–g represent 10 μm.

To test the effects of RIC-3 and rapsyn on α9α10 heteromeric receptors, we examined α-Bgtx labeling in transiently transfected CL4 cells. For transfection, we used α9 and α10 constructs made with YFP and Venus constructs, respectively, in combination with RIC-3 and/or rapsyn. CL4 cells transfected only with nAChRα9 and α10 demonstrate α-Bgtx labeling that is concentrated along the peripheral edges of the cell (Fig. 5e). The addition of RIC-3 expression did not enhance α-Bgtx labeling and in many cases, we observe cells that had little or no α-Bgtx labeling (Fig. 5f). Simultaneous co-expression of rapsyn with nAChR α9, nAChR α10 and RIC-3 increases α-Bgtx labeling above that observed with nAChR α9 and α10 subunits (Fig. 5g). Quantitative analysis of α-Bgtx:YFP colocalization, shows that rapsyn expression enhances α-Bgtx labeling by at least three times that of nAChR α9α10 transfection alone (Fig. 5h). Although, RIC-3 co-localizes with YFP expression on the cell surface (data not shown), it shows no effect on enhancing the amount of α-Bgtx labeling in transfected CL4 cells. These results further suggest that rapsyn more so than RIC-3 enhances cell surface expression of α9 containing nAChRs in mammalian cultured cells.

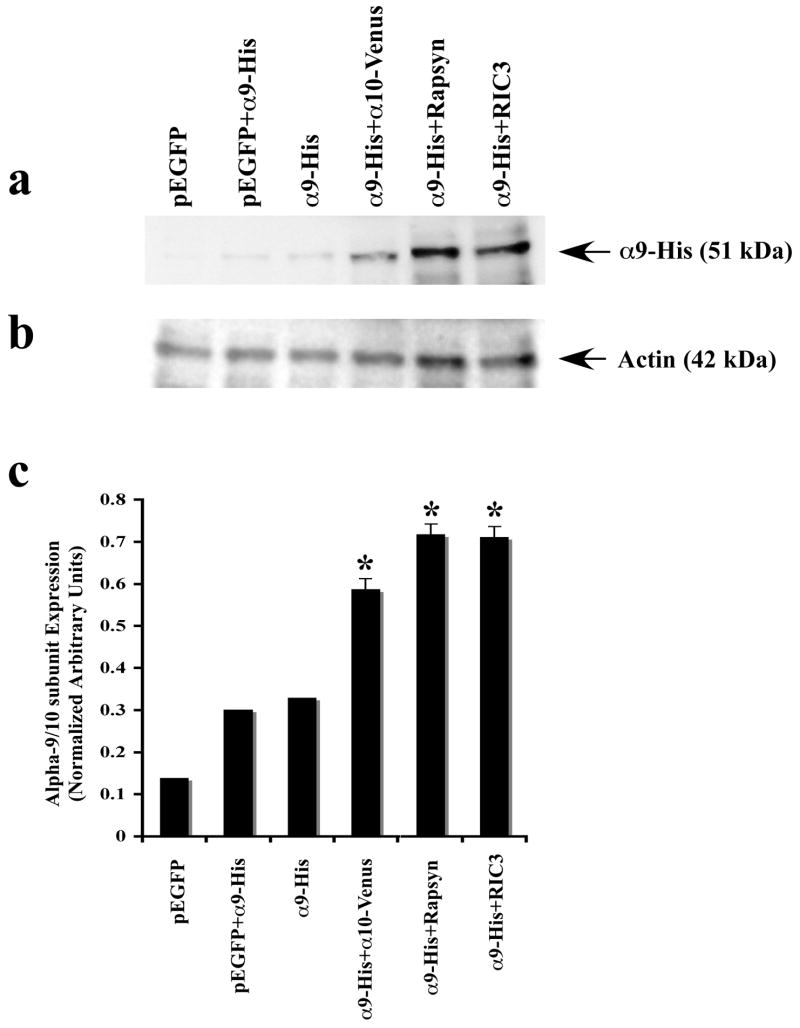

Our results with HEK293T and CL4 transfected cells raise the possibility that increased a-Bgtx binding shown with rapsyn co-transfection could be the result of increased a9 expression. Recently, it has been reported that co-expression of RIC-3 significantly enhances the recruitment of 5-HT3A receptors but has no effect on facilitating α9 or 10 receptors in cultured mammalian cell lines (Cheng et al., 2005; Lansdell et al., 2005). Since our results show that rapsyn but not RIC-3 has a greater effect on nAChR binding to α-Bgtx, we decided to test whether rapsyn or RIC-3 co-expression alters the total receptor expression level. We prepared total lysates and subjected them to Western blot analysis using an anti-His antibody (Fig. 6a). The endogenous expression levels of nAChR α9 protein are increased when the nAChR α10 subunit, rapsyn or RIC-3 are present, but not when an unrelated protein is co-expressed (Fig. 6a, 6c). The most significant enhancement of protein expression occured at equimolar or 1:2 ratios, with diminishing additional effects at higher ratios (data not shown). Our results suggest that nAChR α10, rapsyn and RIC-3 may promote or facilitate nAChR α9 subunit protein expression. However, this increased protein expression at least for RIC-3 does not necessarily lead to significantly higher α-Bgtx labeling. Thus, the increased α-Bgtx labeling (see Figure 5) cannot be explained by just rapsyn increasing overall α9 expression levels.

Figure 6.

Expression of nAChR α9 subunit in cultured CL4 cells transfected with various cDNA constructs as described in Methods. (a) Immunoblots of α9 in the presence of α10, rapsyn and RIC-3. No α9 expression was observed when CL4 were transfected with pEGFP alone. Both co-transfection of α9 with pEGFP and nAChR α9 transfection alone showed low levels of α9 protein. Co-transfection of α9 with α10 increased α9 protein expression. Co-transfection of nAChR α9 with either rapsyn or RIC-3 showed the highest levels of nAChR α9 protein expression. (b) Blots were stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibody to confirm equal protein loading and comparable expression levels. (c) Quantification of nAChRα9 protein bands is plotted as normalized relative arbitrary density units. Data are means of three independent experiments (n = 3), each performed in duplicate. Significant differences, determined by two-tailed student t-test, are indicated (*, p < 0.05). A statistically significant difference was observed between α9 protein expression levels in CL4 cells.

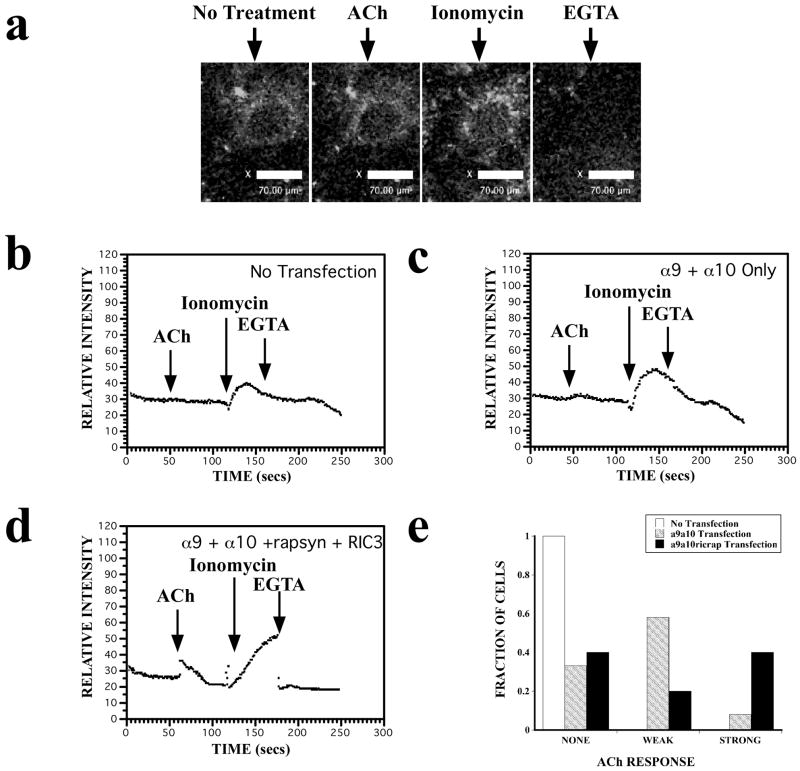

Effect of Rapsyn and RIC-3 Expression on Intracellular Calcium Flux

Micromolar concentrations of acetylcholine (ACh) act as a highly specific agonist of α9 containing nAChRs. To date, reports of functional expression of nAChRs α9α10 in cultured mammalian cells are rare (Fucile et al., 2006; Lansdell et al., 2005; Nie et al., 2004). Because, in addition to mediating fast neurotransmission, the functional role of nAChRs is related to their Ca2+ permeability (Fucile et al., 2006), we examined whether co-expression of rapsyn and RIC-3 increases intracellular Ca2+ levels in cultured mammalian cells. Relative intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) changes were analyzed in CL4 cells expressing full-length nAChR α9 and α10 subunits tagged with YFP and Venus, respectively, along with rapsyn and RIC-3, using the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4-AM. The YFP-expressing cells were well below saturating intensity levels, which allowed us to detect corresponding changes in Fluo-4-AM intensity levels. Both transfected and non-transfected CL4 cells gave rise to large fluorescence changes in the presence of ionomycin that could be easily quenched by the addition of EGTA verifying our ability to detect fluorescence changes. Addition of 100 μM ACh agonist elicits small, but detectable changes in the Fluo-4-AM fluorescence in YFP-expressing CL4 cells (Fig. 7a). Non-transfected cells show no response to ACh, indicating that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ flux is specific to α9α10 receptor subunits (Fig. 7b). Similarly, cells transfected with EGFP alone show no response to ACh (data not shown). CL4 cells transfected with α9α10 alone gave rise to small, changes in relative fluorescence (Fig. 7c). Co-expression of rapsyn and RIC-3 substantially increases the ACh-induced [Ca2+]i fluxes in α9α10 transfected cells leading to more robust fluorescence intensity responses (Fig. 7d). Figure 7e gives the fraction of cells that responded to ACh treatment with no response, a small response (< 10 relative fluorescence units), or a large response (> 10 RFU). We collected relative intensity data on CL4 cells that had no transfection (n=40), α9α10-YFP transfection (n=38), or α9α10-YFP, rapsyn and RIC-3 transfection (n=28). Out of 38 cells transfected with α9α10-YFP cDNAs, 13 cells had no response, 22 showed a weak response, and 3 had a strong response. Out of 28 cells transfected with α9α10-YFP, rapsyn and RIC-3 cDNAs, 11 cells gave no response, 5 cells gave a weak response, and 12 cells gave a strong response. These results suggest that nAChR α9α10 [Ca2+]i responses are enhanced by rapsyn and RIC-3 co-transfection.

Figure 7.

The expression of rapsyn and RIC-3 increases intracellular calcium levels in nAChR α9α10 transfected CL4 cells as indicated by changes in Fluo-4 fluorescence. In all experiments, ionomycin showed maximum calcium responses and EGTA showed minimum calcium responses as indicated by arrows. All functional responses wer measured as agonist-induced elevations in intracellular calcium, and presented as relative mean intensity for each experiment. Three to five independent experiments were performed in duplicate. (a) Representative images of fluorescence changes in a CL4 cell transfected with nAChR α9α10 cDNAs, loaded with Fluo-4-AM dye (10 μM) and bathed in Ca2+ -containing medium HBSS (Hanks Balanced Salt Solution). Shown are fluorescence images before and after ACh treatment, after ionomycin treatment, and after EGTA treatment. (b) Representative fluorescence changes versus time from non-transfected CL4 cells show no response to 100 μM ACh but do show maximal and minimal responses to ionomycin and EGTA, respectively. (c) Representative fluorescence changes versus time from CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9 α10 subunit cDNAs. There is a small increase in fluorescence upon application of 100 μM ACh. (d) Representative fluorescence changes versus time from CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9, α10, rapsyn, and RIC-3 cDNAs. A larger fluorescence response is shown upon application of 100 μM ACh. (e) The fraction of cells that responded to ACh treatment with no response, a small response (< 10 relative fluorescence units), or a large response (> 10 RFU). Data was collected from 40 cells that had no transfection, 38 cells that had α9α10-YFP transfection, and 28 cells that had α9α10-YFP, rapsyn and RIC-3 transfection.

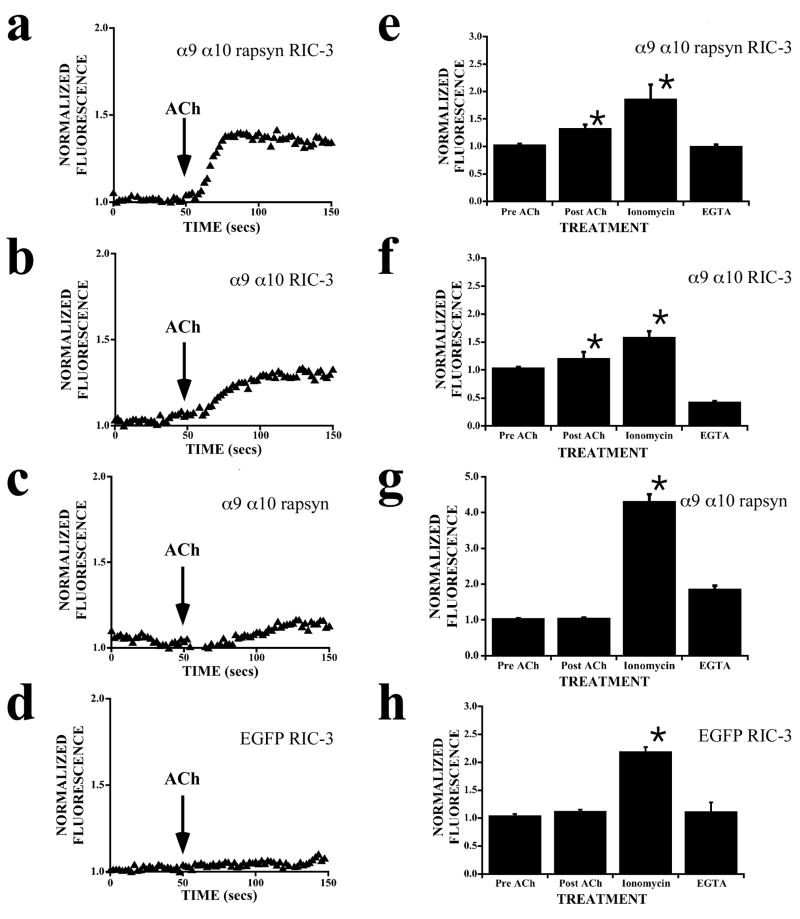

The Fluo-4 fluorescence data raise the possibility that rapsyn and RIC-3 may either singly or both contribute to increases in [Ca2+]i levels. We therefore further tested the effects of rapsyn and RIC-3 separately on nAChR α9α10 transfected CL4 cells. Loading CL4 cells with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, X-rhod-1, allowed the simultaneous visualization of transfected YFP expressing cells separately from changes in [Ca2+]i levels. When transfected with nAChR α9, α10, rapsyn and RIC-3 cDNAs, ACh-evoked responses in CL4 cells produced consistent increases in normalized fluorescence (Fig. 8a). When transfected with nAChR α9, α10, and RIC-3 cDNAs, ACh-evoked responses also showed increases in normalized fluorescence (Fig. 8b). In contrast, CL4 cells transfected with α9 α10 and rapsyn cDNAs showed complex responses that did not significantly change from base line fluorescence (Fig. 8c). Control experiments done with CL4 cells transfected with EGFP and RIC-3 did not show any responses to ACh application (Fig. 8d). Further, CL4 cells transfected with various construct combinations elicited robust ionomycin and EGTA responses (Figs. 8e–h). This result suggests that transfection and overexpression of different combinations of these constructs did not adversely affect normal rises in [Ca2+]i levels. Averaged responses from α9α10 transfected CL4 cells indicate that rapsyn and RIC-3 co-expression show [Ca2+]i increases of 30–40% whereas RIC-3 co-expression shows an increase of about 20% (Figs. 8e,f). Taken together, these results suggest that rapsyn and RIC-3 expression may be necessary and sufficient for the formation of functional heteromeric nAChRs α9α10 on the surface of mammalian cells.

Figure 8.

Effect of RIC-3 and rapsyn expression on ACh-evoked cytosolic calcium levels in α9α10 transfected CL4 cells. Following transfection, CL4 cells were loaded with X-rhod-1, and fluorescence was monitored. (a–d) Representative normalized (F/F0) fluorescence changes versus time are shown before and after addition of 100 μM ACh. (e–f) Bar graphs show averaged fluorescence responses (mean ± S.E.) from a minimum of 20 transfected CL4 cells in response to 100 μM ACh, 5 μM ionomycin, and 30 mM EGTA. (a) Normalized (F/F0) fluorescence fromα9-α10-rapsyn-Ric3 transfected CL4 cells increases by roughly 40% in response to 100 μM ACh. (b) Normalized (F/F0) fluorescence fromα9-α10-Ric3 transfected CL4 cells increases by roughly 25% in response to 100 μM ACh. (c) Normalized (F/F0) fluorescence from α9-α10-rapsyn transfected CL4 cells does not change significantly from base line in response to 100 μM ACh. (d) Normalized (F/F0) fluorescence from EGFP-Ric3 control transfected CL4 cells shows no response to 100 μM ACh. (e) The bar graph shows averaged fluorescence responses from α9-α10-rapsyn-Ric3 transfected CL4 cells (n=20 transfected; mean ± S.E.; p < 0.01). (f) The bar graph shows averaged fluorescence responses from α9-α10-Ric3 transfected CL4 cells (n=20 transfected; mean ± S.E.; p < 0.01). (g) The bar graph shows averaged fluorescence responses from α9-α10-rapsyn transfected CL4 cells (n=20 transfected; mean ± S.E.; p < 0.01). (h) The bar graph shows averaged fluorescence responses from EGFP-Ric3 control transfected CL4 cells (n=20 transfected; mean ± S.E.; p < 0.01).

Discussion

Little information is available on the molecules that induce assembly of nAChRs at synapses outside of the NMJ. In the present study, we show that MuSK, rapsyn and RIC-3, three molecules implicated in different aspects of nAChR assembly and clustering at the NMJ, are also expressed in rodent hair cells and may be differentially regulated during development. We also show that nAChR clusters form during the early period of development on IHCs and OHCs. Although rapsyn is expressed in central and peripheral nervous systems and can initiate clusters in heterologous expression systems, it is not essential for clustering of, for example, ganglionic neuronal nAChRs (Feng et al., 1998). However, our study strongly argues that not only is rapsyn capable of clustering α9 containing nAChRs, but also that RIC-3 leads to increased functional expression at least in heterologous cells. Our data also provide evidence that rapsyn can selectively interact with nAChRα subunits. The present studies were limited mostly to biochemical and in vitro cellular approaches. Although genetic approaches to the study of the NMJ are highly informative, the analogous experimental models for the study of the development of cholinergic synapses in the inner ear are of limited use since nicotinic synapses do not form until after E18 when mice, for example, with null mutations of rapsyn (−/−) do not survive. Conditional knockouts may be informative for future studies.

Confirming the expression of these nAChR-associated molecules in the rodent inner ear, both our PCR and immunostaining experiments show that both rapsyn and RIC-3 are localized to rodent hair cells. At early postnatal ages, rapsyn is localized to the basal regions of IHCs and OHCs, while RIC-3 is diffusely expressed throughout IHCs and OHCs. Consistent with a transient IHC efferent innervation, both rapsyn and RIC-3 localize preferentially to OHCs within the organ of Corti at older ages. The PCR expression profile of rapsyn mimics α9 while the PCR expression profile of RIC-3 mimics α10. The data further show that the α9 containing nAChRs are able to co-localize with rapsyn or RIC-3 in the cytoplasm and possibly near or at the cell surface of HEK293, QT6 and CL4 cells. We found that rapsyn forms α-Bgtx-labeled aggregates of nAChRs characterized by distinct, punctate clusters in these cells. These results are in agreement with previous studies that show rapsyn forms high density clusters when expressed alone in QT6 cells, and that co-expression of nAChR subunits with rapsyn results in reorganization of the subunits into high density clusters that are precisely co-localized with rapsyn clusters (Eckler et al., 2005; Gautam et al., 1995; Maimone and Enigk, 1999).

At the NMJ, current models suggest that muscle nAChRs and rapsyn are co-targeted to the plasma membrane as a complex. These nAChR-rapsyn complexes may include other postsynaptic proteins such as MuSK, Src kinases, utrophin and α/β-dystroglycan (Eckler et al., 2005; Fuhrer et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2001; Maimone and Enigk, 1999; Moransard et al., 2003; Willmann and Fuhrer, 2002). Previous reports with rapsyn fragments expressed in HEK293T cells along with muscle nAChRs, have established that the rapsyn coiled-coil domain is necessary for nAChR clustering (Bartoli et al., 2001; Ramarao et al., 2001). A rapsyn-mediated clustering of α9 containing nAChRs in sensory hair cells may utilize a similar signaling mechanism. Sequence analysis of partial rapsyn transcripts isolated from the inner ear revealed that cochlear rapsyn is highly homologous to muscle rapsyn. It has been established that the major cytoplasmic loop of nAChR α subunits is located between the M3 and M4 transmembrane regions and is necessary and sufficient to mediate co-clustering with rapsyn (Maimone and Enigk, 1999).

Using a yeast two-hybrid approach based on hSoS recruitment (Aronheim, 2000) our study provides evidence that rapsyn interacts selectively with the cytoplasmic loop of nAChR α9. That the intracellular domain of the nAChRα9 subunit and not the nAChRα10 subunit interacts preferentially with rapsyn has functional implications. We show that the coiled-coil regions known to interact with muscle AChRs also interact with the hair cell nAChR subunits, but not the way we expected. Since nAChRα9 is essential for functional expression of the hair cell nAChR, we expected that clustering interactions occurred either predominately through nAChRα10 because of its developmental profile with efferent synaptogenesis or equally through α10 and α9 because of their homology. Although they share as much as 53% identity at the amino acid level, α9 and α10 nicotinic receptors have cytoplasmic regions that are highly variable. Such amino acid sequence variability could account for the preferential interaction of rapsyn with the α9 and not α10 subunit. In addition, in vitro and in vivo co-IP analyses demonstrate direct binding of rapsyn with the nAChR α9 subunit. We also found that rapsyn colocalizes with the nAChR α9 subunit when co-expressed in heterologous cells. Indeed, hair cells form distinct clusters of nAChRs during the period of efferent synaptogenesis. Our heterologous cell expression and in vivo co-IP studies raise the possibility that a rapsyn-mediated clustering pathway may exist in both IHCs and OHCs during efferent synaptogenesis. However, for functional expression of nAChRs α9α10 in heterologous cells, rapsyn was not sufficient.

Recently, the human homolog RIC-3 has been shown to bind to α7 nAChRs and enhances their functional expression in Xenopus Laevis oocytes and mammalian cells (Castillo et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005). However, the precise mechanisms by which the hRIC-3 protein exerts its effects on nicotinic receptors are not known. It has been reported that the N-terminal and the C-terminal regions of hRIC-3 are involved in its action on α7 nAChRs (Ben-Ami et al., 2005) and 5HT3Rs (Cheng et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2005). Because of the close sequence similarity between nAChRα7 and nAChR α9 subunits (42% identity at the amino acid level), we utilized in vitro and in vivo co-immunoprecipitation analyses and confirmed that α9 and hRIC-3 are able to co-associate directly in HEK293T cells and cochlear tissues. Such direct interaction may be necessary for proper assembly or targeting of nAChR α9 subunits to the cell surface.

Our study is in agreement with studies that find co-expression of RIC-3 has no effect on binding of 125I-α-Bgtx with either α9 homomeric or α9α10 heteromeric receptors (Lansdell et al., 2005). We hypothesized that RIC-3 co-expression might enhance the effect of rapsyn on α-Bgtx clustering at the cell surface. Our data show RIC-3 has little effect on α-Bgtx binding in HEK293T cells co-expressing nAChR α9 and rapsyn. This result suggests that RIC-3 is not necessary for clustering of α9 containing nAChRs in mammalian cells. However, we did find that RIC-3 expression increases total amount of α9 receptor protein level in CL4 cells, supporting the concept that RIC-3 acts to regulate nAChR trafficking by increasing the fraction of mature or correctly folded receptor subunits needed to reach the cell surface. Another possibility is that RIC-3 regulates the turnover of the α9 receptor subunits. Future experiments will be aimed at exploring this possibility and further delineating the role of RIC-3 on α9 containing nAChRs.

Importantly, our study provides evidence that the expression of RIC-3 increases heteromeric α9α10 receptor-induced [Ca2+]i responses, suggesting that rapsyn and RIC-3 promote the formation of functional α9α10 receptors on the surface of mammalian cells but in different ways. Although nAChRs α9α10 are capable of producing small changes in [Ca2+]i levels, the co-expression of rapsyn and RIC-3 in α9α10 transfected CL4 cells causes much larger [Ca2+]i changes in response to ACh treatment. Because rapsyn facilitates α-Bgtx clustering at the cell surface, we expected that rapsyn would also contribute significantly to these ACh-induced-[Ca2+]i responses. Instead, we observed robust ACh-induced [Ca2+]i responses to CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9, α10, and RIC-3 cDNAs and little or no responses to CL4 cells transfected with nAChR α9, α10, and rapsyn cDNAs. Previous studies have suggested that co-expression of RIC-3 promotes functional expression of other α subunits, e.g., α8, but not homomeric α9 or heteromeric nAChRs α9α10 in mammalian cell lines such as human kidney tsA201 cells (Lansdell et al., 2005). The only previous demonstrations of functional α9 containing nAChRs in a mammalian cell line have been in transiently transfected rat pituitary GH4C1 cells (Fucile et al., 2006) and HEK cells co-expressing SK2 (Nie et al., 2004). Our ACh-induced calcium responses are similar to those recently shown by Fucile et al. (2006) where they correlated calcium imaging transients directly with patch clamp recordings. Although rapsyn may mediate clustering of α9 containing nAChRs and thus enhance α-Bgtx labeling, RIC-3 seems responsible for giving rise to enhanced functional expression. The observed calcium responses could be due to RIC-3 modulation of receptor composition, e.g., less α9 homomeric and greater α9α10 heteromeric. However, both in oocytes and cultured mammalian cells, the simultaneous expression of both α9 and α10 subunits yield larger calcium responses than those obtained with the nAChR α9 subunit alone (Katz et al., 2000; Fucile et al., 2006). Since there are no known ionotropic responses of an α10 homomeric receptor, changes in receptor subunit composition would be limited to homomeric α9 receptors versus heteromeric α9 and α10 combinations. A more plausible suggestion is that RIC-3 indirectly increases nAChR α9-induced calcium responses by affecting trafficking and assembly of the receptor on the cell surface, and/or it may directly affect the protein expression of the receptors.

Most attempts to express α9 and/or α9α10 in mammalian cells have been difficult and appear to require the addition of some accessory protein (Nie et al., 2004). We believe that the problems associated with heterologous expression of nAChRs α9α10 in various cultured mammalian cell lines can be circumvented by co-expression of specific accessory proteins. Since different cell lines may or may not express these accessory proteins, it is likely that the use of different cell lines has yielded different results regarding nAChR α9α10 functional expression. RT-PCR studies have provided evidence of a correlation between the endogenous expression of RIC-3 transcripts and the ability of cells to express functional α7 nAChRs (either endogenously or from heterologous expression of nAChRα7 cDNA) (Lansdell et al., 2008; Lansdell et al., 2005; Williams et al., 2005). For example, although tsA201 cells contain no RIC-3 mRNA, GH4C1 cells show detectable levels of endogenous RIC-3 mRNA as determined by RT-PCR (Lansdell et al., 2005). Studies conducted in different expression systems suggest that additional host cell factors may modulate the nAChR chaperone activity of RIC-3 (Lansdell et al., 2008). It is possible that GH4C1 cells could have other endogenous molecules that participate in nicotinic clustering mechanisms. Neither HEK 293T cells nor CL4 cells used in this study have any endogenous expression of either rapsyn or RIC-3. Further studies are necessary to differentiate the exact role(s) of each of these accessory proteins. It is likely that functional expression of nAChRs α9α10 in various mammalian cell lines depends on the expression of these as well as other endogenous factors that participate in receptor clustering and assembly (Lansdell et al., 2005).

The neuronal nAChRs α9α10 are expressed within hair cells of the inner ear and have been implicated in synapse formation and auditory processing (Elgoyhen et al., 1994; Elgoyhen et al., 2001; Vetter et al., 1999). These nAChRs are also expressed in other diverse tissue locations such as the dorsal root ganglia (Ellison et al., 2006; Lips et al., 2002), lymphocytes (Lustig et al., 2001; Peng et al., 2004), and sperm (Kumar and Meizel, 2005). Since these receptors have been difficult to study in mammalian heterologous expression systems, very little is known about the accessory molecules that regulate the function of these neuronal nAChRs. This study is the first to investigate the signaling molecules that could be involved in cholinergic synapse formation in the inner ear. Based on the data presented, our study raises the possibility that a synaptic scaffold similar to the NMJ may be present in inner ear sensory cells and other tissues expressing nAChRs containing α9 subunits. Such a synaptic scaffold could be critical for the transient assembly and clustering of nAChRs in IHCs prior to the onset of hearing. Previous studies have suggested that IHCs may at least transiently express α9 containing nAChR subunits and may be inhibited by ACh (Glowatzki and Fuchs, 2000; Morley and Simmons, 2002; Simmons and Morley, 1998). The inhibition of IHCs could be important for the maturation of IHC and auditory nerve responses such as the generation of low frequency bursts of action potentials (Simmons, 2002). Whether rapsyn-mediated clustering and RIC-3 mediated assembly of α9 containing nAChRs play a role in early IHC responses requires further investigation. Continued characterization of the nAChR α9α10 signaling cascade will shed light on how these cholinergic receptors are formed, regulated and possibly disassembled in the inner ear and elsewhere.

Experimental Methods

Animal and tissue preparation

Sprague-Dawley rats and C57BL6 mice ranging in age from embryonic day 16 (E16) to young adult (6 weeks) were either bred in-house or obtained from Harlan Labs (Indianapolis, IN). Appearance of the vaginal plug was representative of gestation day 1 (E1). For embryonic and postnatal animals, the crown-to-rump lengths were measured and used to verify the developmental stage of each animal. All animals were euthanized with near-lethal intraperitoneal injections of sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, 100 mg/kg) or by hypothermia (only animals less than 1 week). The day of birth (E21 for rats; E19 for mice) represented postnatal day 0 (P0). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee and conducted according to the guidelines for Animal Research at Washington University school of Medicine.

Whole organ of Corti and hair cells RT-PCR

Following anesthesia and temporal bone removal, the organ of Corti was microdissected and immediately placed into RNA extraction solution (Qiagen, La Jolla, CA). Total RNA was isolated and resuspended according to manufacturer’s instructions. Different amounts of RNA were then used as template for RT-PCR reaction. Reverse transcription reactions using random hexamers and the Retroscript kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas) were performed at 42°C for 60 minutes. Primers were designed to amplify a unique 378-bp fragment of intracellular loop of nAChR α9 subunit sequence (GenBank Accession #NM_022930), a 280-bp fragment of intracellular loop of nAChR α10 subunit sequence (GenBank Accession #NM_022639), a 303-bp fragment of rapsyn sequence (GenBank Accession #NM009023), a 422-bp fragment of RIC-3 sequence (GenBank Accession #NM_178780), and a 220-bp or 450-bp fragment of GAPDH (Clontech). The GAPDH (G3P) primers were used as internal controls. Forward and reverse primers of each fragment were as follows: nAChR α9 (forward: 5′attcacttctgtggagc3′ and reverse: 5′ccactcgctgcccttggag3′); nAChR α10 (forward: 5′ctgcactactgtggccc3′ and reverse: 5′cttccaatcttcgtggcgg3′); rapsyn (forward: 5′gcccacaacaacgatgac3′ and reverse: 5′gacagacgagacgaaacg3′); RIC-3 (forward: 5′atggaggactgggaaggtaaaatg3′ and reverse: 5′aagagaagcacagtatgtccaa3′); MuSK (forward: 5′tgccgaaggaggaaagaatg3′ and reverse: 5′gataccacaccaggagaccc3′). Purified populations of rat OHCs were also obtained using a previously described technique (Glowatzki and Fuchs, 2000) from the apical turns of 2-week-old rats. Typically, 200 hair cells were harvested at one time, and this population was used for subsequent molecular experiments. Different primers were also designed to amplify unique 680-bp and 222-bp fragments of rapsyn sequence. All the PCR reactions were performed at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 2 min, one cycle of 72 °C for 10 min, and a 4 °C hold. Amplified PCR products were run on 1% agarose gel. Candidate bands were cut out and sequenced to confirm identity.

DNA constructs

Cloning of full-length human α9 and α10 acetylcholine receptor subunits (complete coding sequences of nAChR α9, 1440 bp; nAChR α10, 1353 bp) were isolated by standard PCR techniques. The PCR products were then subcloned directly into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA4/HisMax-TOPO according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Full-length of rat α9 and α10 receptor subunit complete coding regions were also isolated by standard PCR and subcloned into mammalian expression vectors pEGFP-C1 (Clontech) and pCS2-Venus (a generous gift from Dr. Atsushi Miyawaki, Riken Brain Science Institute, Japan) respectively. Following subcloning, their identity and proper reading frame was confirmed. Full-length mouse rapsyn was subcloned using the eukaryotic expression vector pCI (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) kindly provided by Dr. Joe Henry Steinbach, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, USA. Full-length human RIC-3 was subcloned into pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen) kindly provided by Dr. Millet Treinin, Hebrew University-Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, Israel.

Yeast two-hybrid mating of nAChR (amino acid 322–448) α9 or α10 subunit vs. rapsyn

We used the Matchmaker Gal4 Two Hybrid System 3 (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto CA). The intracellular loops of the human nAChR subunits α9 (ICD, amino acid 322–448) and α10 (ICD, amino acid 323–416) were amplified using standard PCR technique and sub-cloned into the Clontech yeast-two-hybrid vector pGBKT7. A portion of either rat cochlear or muscle rapsyn (coiled-coil domain, CCD; amino acid 298–332) protein was amplified and subcloned into the Clontech yeast-two-hybrid vector pGADT7. Construct inserts were sequenced to be sure the fusion proteins were in-frame and that no mutations were introduced. The yeast line AH109 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was then co-transfected with pGADT7-rapsyn and either pGBKT7-α9 or pGBKT7-α10 using the LiAc technique according to manufacturer’s directions. Transformed yeast were then plated on the following media: SD/-Trp (selecting for the pGBD vector), CD/-Leu (selecting for the pGAD vector), SD/-Trp-Leu (selecting for co-transformants), and SD/-His-Leu-Trp (selecting for a weak two-hybrid interaction) and SD/-Ade-His-Leu-Trp (selecting for a strong two-hybrid interaction). After 5 days, growth on each plate was scored as 4+ (>1000 colonies/plate), 3+ (100–1000 colonies/plate), 2+ (11–100 colonies/plate), 1+ (1–10 colonies/plate), or 0 (no growth).

Matchmaker in vitro immunoprecipitation

In vitro immunoprecipitation (IP) was used to independently confirm putative protein–protein interactions. After detecting protein–protein interactions through the in vivo yeast two-hybrid screen, the vectors were used directly in the in vitro transcription–translation reaction that was performed by using the rabbit reticolocyte lysate system (TNT kit; Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was incubated for 90 min at 30°C in the presence of S35 methionine. Proteins were transcribed and translated in vitro from positive control vectors pGBKT7-murine p53 fused with c-Myc epitope and pGADT7-SV40 large T-antigen fused with HA epitope. These vectors were also used as positive controls because murine p53 and SV40 large T-antigen associate during an in vivo co-IP and interact in vitro during a yeast two-hybrid screen (Clontech kit). Product proteins (S35-α9 + cMyc tag and S35-rapsyn + AHtag) were mixed, split into two tubes, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The anti-AH antibody was then added to one of the tubes and the anti-cMyc antibody to the other tube. The complex was isolated after a 1 h incubation at room temperature by binding to protein A beads. The beads were washed following the manufacturer’s instructions and resuspended in Lammli buffer, heated for 5 min at 80°C, and electrophoresed in 15% SDS-PAGE gel. Kodak (Rochester, NY) x-ray films were exposed on the dry gels and developed, or the dry gel was visualized by autoradiography. The translated products were also incubated with c-Myc or HA antibodies and protein A and analyzed by Western blot (see below).

Culture and transfection of mammalian cells

HEK293T and QT6 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The HEK293T cells were maintained at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin/streptomycin mix at 1:1000. QT6 cells were grown at 37° C in Medium-199 containing Earle’s salts supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 10% Tryptose phosphate broth with penicillin/streptomycin. CL4 (LLC-PK1) cells kindly provided by Dr. James Bartles (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA) were grown at 37°C in MEM alpha medium 1X with L-glutamine and without ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleotides (Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were plated on uncoated glass coverslips (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) placed in 35 mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to reach relatively high density (70–90% confluency). For Western blotting and immunoprecipitation experiments (below), 3×105 cells were plated on a 6-cm dish. After 24 hours the cells were transfected with α9, α10 along with rapsyn or RIC-3 DNA constructs (~ 2 μg) in equal molar ratios. All transfections were performed with lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and transfection efficiency, estimated to be 60–85% monitored by expression of a green fluorescent protein vector (pEGFP-C1, Clontech). Cells were examined for protein expression 24–48 hour after transfection.

Western blotting

HEK293T and CL4 cells were harvested by rinsing the 60-mm dish twice with ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS), and lysed in lysis buffer containing (50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 2mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail). Cells were scraped, sonicated, and lysates were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and rotated at 4°C for 45 minutes. Laemmli SDS sample buffer was added to proteins and equal amounts of cell lysates were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad), and blocked for 1 hour with 5% milk in TBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS-T). Membranes were incubated with His antibody (Clone 4D11, mouse monoclonal IgG, Upstate, Lake Placid, NY) at a 1:1000 dilution for the detection of nAChR α9 and the immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with the actin antibody (Sigma) to ensure equal protein loading, rapsyn antibody (MA1-746, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO) at a 1:1000 dilution, and sheep polyclonal anti-RIC-3a antibody (a generous gift from Dr. Christopher Connolly, University of Dundee, Scotland) at a 1:500 dilution. The blots were washed three times with TBS-T followed by incubation for 1 hour with a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate (BioRad) or rabbit anti-sheep HRP conjugate (Pierce). Membranes were subsequently washed three times (10 min each wash) with TBS-T and developed with the Super signal ECL reagent (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitation

Total lysates from HEK293T cells were prepared as mentioned previously. To obtain mouse cochlear lysates, cochleae were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer containing (50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 25 mM β–glycerophosphate, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail). Lysates were rotated at 40C for 1 hour and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 minutes to remove the insoluble fraction. A portion of the total lysate was saved for protein immunoblotting.

To imunoprecipitate the nAChR α9 subunit, 10 μl of anti-α9 subunit (E-17, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody were added to the lysates and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. Afterwards, 50 μl of protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) was added, and the solution incubated overnight to capture the immunoprecipitates. Protein A beads were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes, washed three times with lysis buffer, and bound proteins eluted with 45 μl of 2X Laemmli SDS sample buffer. Proteins were then analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against rapsyn, or RIC-3a as described above.

Immunofluorescence staining

HEK293T and CL4 cells transiently expressing full-length of human nAChR α9/α10 + mouse rapsyn, or full-length of human nAChR α9/α10 + mouse rapsyn + human RIC-3 were plated on uncoated glass coverslips (Fisher Scientific) placed in 35 mm tissue culture dishes and allowed to reach high density. Cells expressing a green fluorescent protein EGFP were used as controls. Thirty-six hours post-transfection, cells were incubated with Alexa-Fluor 488-labeled-α-bungarotoxin (α-Bgtx) or with Alexa-Fluor 594-labeled-α-Bgtx for EGFP controls at 1:100 dilution for 1 hours at room temperature. After incubation the α-Bgtx was removed, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed with TBS, and incubated with blocking buffer (TBS with 5% BSA or donkey serum). Cells were then incubated overnight with primary antibodies: α9 goat polyclonal antibody (E-17, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100 dilution, rapsyn mouse monoclonal antibody (MA1-746, Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO) at 1:500 dilution, RIC-3b sheep polyclonal (a generous gift from Dr. Christopher Connolly, University of Dundee, Scotland) at 1:200 and anti-GFP mouse monoclonal antibody (mab3580, Chemicon) at 1:250 in blocking buffer containing (TBS, 2 % BSA or donkey serum). Alexa flour conjugated secondary antibodies made in donkey were used at 1:500 dilution as appropriate and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature.

To label nAChRs in the inner ear with α-Bgtx, sensory organs were isolated and immediately immersed in oxygenated Hank’s buffer and incubated with fluorescently tagged α-Bgtx following either mechanical dissociation or sectioning. For immunocytochemistry, inner ear sections or dissociated organs were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and incubated with primary antibodies against vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) and calbindin (hair cell marker, 1:2000 dilution, Swant). Most preparations were also pre- or post-labeled with fluorescent phalloidin to label the hair-cell stereocilia. Muscle tissue isolated from rat diaphragm was processed as above and used as controls.

Immunocytochemistry

For immunocytochemical experiments, we used a minimum of three (3) animals at each age time point. For each animal, one ear was typically used for sensory organ whole mount preparations and one ear used for Vibratome sectioning. In multiple labeling experiments, antisera were applied to serial tissue section sets that included one section for multiple labeling and single labeling control sections. Primary antisera were against rapsyn (anti-mouse, 1:500, MA1-746, Affinity Bioreagents), α9 subunit (anti-goat, 1:100, E-17, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), RIC-3b (anti-sheep, 1:200). Primary antibodies were made in 2% normal chick serum containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and applied to cochlear tissues overnight at 4°C. In certain instances, hair cell bodies were visualized by incubating cochlear tissues with antibodies against rat calbindin (1:2000 dilution, Swant), α-parvalbumin or myosin VI antibodies. Alexa flour conjugated secondary antibodies made in chick were used at 1:500 dilution as appropriate and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature to visualize immunostaining using confocal microscopy. The specificity of primary antisera was confirmed in experiments using secondary antisera in the absence of primary antibody (data not shown).

Measurement of intracellular calcium

CL4 (LLC-PK1) cells expressing full-length of human α-9/10 nAChR subunits along with mouse rapsyn and human RIC-3 were plated on uncoated glass cover slips as described previously. Cells expressing a green fluorescent protein EGFP were used as controls. Intracellular free-calcium (Ca2+) levels were measured using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss-BioRad, Radiance 2000 MP), interfaced to a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope, and the fluorescent Ca2+ indicators Fluo-4-AM or X-Rhod-1-AM dissolved in DMSO (Molecular Probe, Eugene, OR) as described previously (Haynes et al., 2004; Light et al., 2003) with some modifications. Cells were loaded for 1 hour at room temperature with either 10 μM Fluo-4-AM or X-Rhod-1-AM in HBSS assay buffer containing 1.4 mM CaCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The use of these dyes permit the accurate measurement of Ca2+ signals in cells transfected with fluorescent proteins. Equal volumes of the non-ionic detergent pluronic F-127 to that of Fluo-4-AM or X-Rhod-1-AM were used to assist in the dispersion of the non-polar dye in aqueous media and improve loading. To investigate whether activation of these receptor subunits was sufficient to evoke transient Ca2+ levels, 100 μM of acetylcholine was used. Fluo-4-AM and X-Rhod-1-AM were excited at 488 or 585 nm, respectively and the fluorescence intensity of individual cells was measured within one field of view (n ≥ 20 cells). Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured at room temperature, 24–36 hours after transfection, from cells identified under fluorescence microscopy as YFP positive. Identical imaging parameters were maintained for all conditions. All experiments were done in triplicate. Images were captured every 1–2 seconds for about 400 second interval. Maximal fluorescence (maximal cytosolic calcium flux) was obtained at the end of each observation by adding 5–100 μM ionomycin made in DMSO, followed by 10–30 mM EGTA to release Ca2+ from Fluo-4-AM or X-Rhod-1-AM to obtain minimal fluorescence (minimal cytosolic calcium flux).

Imaging

Using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), cells or inner ear sensory organs were sequentially scanned at high (500–1000×) magnification, exciting the green (488 nm), red (543 nm) and far-red (637 nm) channels. Fluorescent emissions were separated with appropriate blocking and emission filters, scanned at slow (50 lines/s) scan speeds for high resolution, and independently detected with 8-bit accuracy by photomultiplier tubes using, if necessary, accumulation was performed to increase signal and reduce noise. Three-dimensional images of serially reconstructed image stacks from the confocal microscope were rendered using Volocity (v4.xx; Improvision, Lexington, MA, USA). Wholemount images in the X–Y plane were digitally rotated and viewed in the X–Z plane. Z-projections of image stacks were also performed. Single images were exported to Canvas (vX, ACD Systems, Canada) and image quality (brightness/contrast or histogram levels) was adjusted to maximize signal and minimize background.

Colocalization

Quantitative colocalization analysis was performed on two fluorescence channels with Volocity software using 3D image stacks obtained from the confocal microscope. Image stacks were captured sequentially to minimize any crosstalk between channels. Threshold values were determined for each channel to minimize signal background. After generating a colocalization map, the colocalization voxels are displayed (masked) in white color and the highlighted colocalization voxels merged to a summed (projected) image. The colocalization coefficients (Mx and My) were calculated for each of the two channels according to the method of Manders et al. (1993).

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. A paired student t-test was used to test for differences between transfectants as appropriate, with P< 0.05 considered significant. We also used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for differences among transfection groups, followed by Tukeys’ post hoc test for comparisons between groups.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Gum and J. Claspell for technical assistance and B. Tong for comments on the manuscript. This work is supported in part by NIH R01 grants to D.D.S. and L.R.L., and an NIDCD P30 Core grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This PDF receipt will only be used as the basis for generating PubMed Central (PMC) documents. PMC documents will be made available for review after conversion (approx. 2–3 weeks time). Any corrections that need to be made will be done at that time. No materials will be released to PMC without the approval of an author. Only the PMC documents will appear on PubMed Central -- this PDF Receipt will not appear on PubMed Central.

References

- Apel ED, Glass DJ, Moscoso LM, Yancopoulos GD, Sanes JR. Rapsyn is required for MuSK signaling and recruits synaptic components to a MuSK-containing scaffold. Neuron. 1997;18:623–635. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias HR. Localization of agonist and competitive antagonist binding sites on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neurochem Int. 2000;36:595–645. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronheim A. Protein recruitment systems for the analysis of protein-protein interactions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1009–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker ER, Zwart R, Sher E, Millar NS. Pharmacological properties of alpha 9 alpha 10 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors revealed by heterologous expression of subunit chimeras. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:453–460. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli M, Ramarao MK, Cohen JB. Interactions of the rapsyn RING-H2 domain with dystroglycan. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24911–24917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ami HC, Yassin L, Farah H, Michaeli A, Eshel M, Treinin M. RIC-3 affects properties and quantity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors via a mechanism that does not require the coiled-coil domains. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:28053–28060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504369200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canlon B, Cartaud J, Changeux JP. Localization of alpha-bungarotoxin binding sites on outer hair cells from the guinea-pig cochlea. Acta Physiol Scand. 1989;137:549–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]