Abstract

It has long been suspected that population heterogeneity, either at a genetic level or at a protein level, can improve the fitness of an organism under a variety of environmental stresses. However, quantitative measurements to substantiate such a hypothesis turn out to be rather difficult and have rarely been performed. Herein, we examine the effect of expression heterogeneity of λ-phage receptors on the response of an Escherichia coli population to attack by a high concentration of λ-phage. The distribution of the phage receptors in the population was characterized by flow cytometry, and the same bacterial population was then subjected to different phage pressures. We show that a minority population of bacteria that produces the receptor slowly and at low levels determines the long-term survivability of the bacterial population and that phage-resistant mutants can be efficiently isolated only when the persistent phage pressure >1010 viruses/cm3 is present. Below this phage pressure, persistors instead of mutants are dominant in the population.

INTRODUCTION

When a sensitive bacterial population is mixed with an antagonistic phage population, a majority of bacteria are rapidly decimated, but a small bacterial population survives. Over time, this minority population multiplies, taking over the entire population despite the presence of phage. Evidence has shown that in many cases, the surviving minority population is not composed of phage-resistant mutants but of cells that display phage sensitivity (1). Even when mutants do appear, a small population of sensitive bacteria has been found to remain (2). If the bacterium/phage relation were parasitic, the coexistence between bacteria and phage would make evolutionary sense. However, such coexistence is commonly found for bacterium/phage relations that are purely exploitative, such as virulent viruses. This peculiar phenomenon has confounded scientists for many years, and various hypotheses have been put forward, which include: 1), the numerical-refuge hypothesis (3,4), where bacteria and phage coexist as a consequence of prey-predator dynamics, i.e., the existence of stable fixed points when the populations are modeled using the principle of mass of action; 2), the arms-race or the Red Queen hypothesis (5,6), where a sequence of gene-for-gene mutations and countermutations in the bacteria and phage allows the stabilization of both populations; 3), the spatial refuge hypothesis (2), which postulates that a heterogeneous environment can protect the sensitive bacteria, which in turn can produce phage; and 4), the physiological refuge hypothesis (7), where a sensitive bacterium can transiently become insensitive or a resistant bacterium can transiently become sensitive. Hypothesis 1 is solidly grounded in mathematics. Because of simple interactions between bacterium and phage, it has held the premise that bacterium/phage population dynamics can be reasonably predicted. To date, however, concrete proof of bacterium/phage coexistence resulting from the stability predicted by the prey-predator-like model is still lacking, and the same perhaps can be said about other interacting biological species. Thus, hypothesis 1 is still a subject of current debate. There is convincing evidence that the arms race between bacterium and phage is not open ended. There appears to be a fundamental difference in the ability of a bacterium and a phage to evolve. Selection of host-range mutants of λ-phage in Escherichia coli showed that the arms race typically lasts for two to three rounds, and in the end, the host always prevails. This asymmetry in the arms race is beautifully demonstrated by the work of Hofnung and colleagues (8) and later by Lenski and Levin (6). Thus, hypothesis 2 is most likely not the biological basis for bacterium/phage coexistence. In a recent experiment, Schrag and Mittler (2) found important differences in bacterium/phage population dynamic experiments carried out using continuous cultures in a chemostat and using serial cultures by daily dilution of samples into fresh medium and flasks. The bacterium/phage coexistence was found in the chemostat but not in serial cultures. The extinction of the phage populations in serial cultures was attributed by these investigators to the elimination of the spatial refuge; i.e., sensitive bacteria can form patches or films on the container walls of the chemostat but cannot do so in serial cultures. Schrag and Mittler's careful experiment lends support to hypothesis 3, indicating the importance of natural habits for the survival of species.

It appears to us that the biologically most interesting hypothesis, namely that of physiological refuge, has never been carefully examined (2). This was perhaps in part because of our incomplete knowledge of the transitory/fluctuating nature of the critical host proteins that are responsible for phage infection and in part because of experimental difficulties in characterizing protein heterogeneity and its effect on bacterium/phage population dynamics. However, the situation has changed considerably in recent years thanks to new understandings of gene-network dynamics (9–13) and to the quantitative characterization of phage binding to cells with a discrete number of receptors (14,15). Specifically, recent investigations of single-gene-expression dynamics have revealed stochasticity at all levels, including transcription (16) and translation (12,13). Such noise appears to be ubiquitous for different gene products and across different cell lines (17). An important consequence of the noise is that it can generate a diverse protein number distribution within the clonal bacterial population. It is therefore not difficult to imagine that if one of the critical genes is subject to large number fluctuations, it would create a varying degree of phage sensitivity within the bacterial population and thus have a profound effect on bacterium/phage population dynamics. Could the stochastic gene expression be the long-sought-after mechanism for the bacterium/phage coexistence? This question forms the theme of the current investigation.

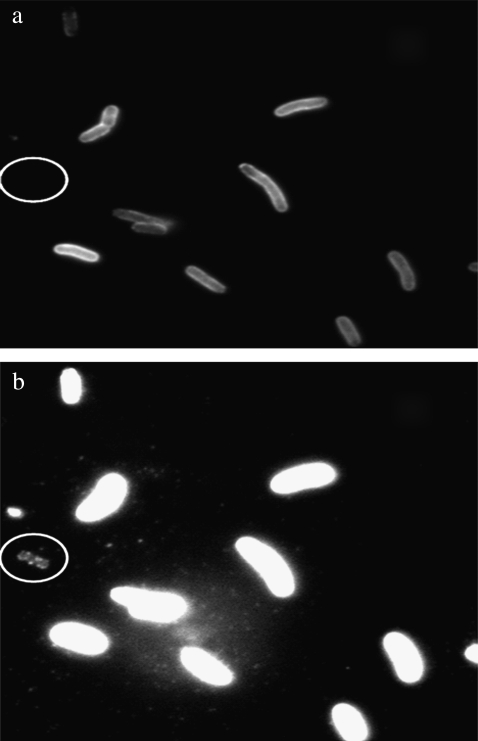

To sharpen our study, we focused on the effect of LamB expression noise on the life and death of a large E. coli population when it is subject to a phage pressure, defined as an initial phage concentration P(0). LamB was chosen because phage binding is the bacterium's first line of defense against infection, and most phage-resistant mutants isolated in laboratories are shown to be defective in the lamB gene (7,18). The investigation is also made possible by a recent finding that fluorescently labeled λ-phage remain infectious and can be used to tag functional LamB receptors in vivo (1). The receptor distribution in the bacterial population can thus be characterized by flow cytometry with near-single-receptor resolution. Indeed, using this fluorescent tagging method, we have found surprisingly large fluctuations in the expression level of functional LamB receptors in individual bacteria even when the maltose operon was fully induced (1). By way of introduction, Fig. 1 shows a fluorescent micrograph that was taken with E. coli Ymel strain tagged with fluorescently labeled λ-phage. These images illustrate vastly different fluorescent intensities for different cells, indicating a significant variation in the number of bound phage, or LamB receptors, on the bacterial cell wall. For bacteria with a small number of receptors, individually bound phage are clearly discernible in the micrograph of Fig. 1 b.

FIGURE 1.

Epifluorescent microscopy of λ-phage bound to bacteria Ymel. The λ-phage are labeled with AlexaFluor-488 and incubated with the bacteria for 40 min (see details in the Methods). The two pictures (a and b) are identical except that the intensity gain is different. Typical bacteria adsorb 200–300 phage particles, yielding brightened cell envelopes. However, a minority of bacteria adsorb a small number of phage particles and can be seen only when a significant gain is applied to the CCD camera as delineated by the encircled cell in b. For bacteria with a small number of LamB receptors, the attached phage can be counted because they appear as individual diffraction-limited spots on the bacterium.

In this study, we find that the receptor expression level is strongly correlated with the population dynamics. For short times, the effective growth rate Λeff of the bacteria is approximately linear in P(0) and is given as Λeff ≈ Λ −  P(0), where

P(0), where  is the bacterium-population-averaged phage adsorption coefficient. This behavior is consistent with Berg and Purcell's theoretical prediction, which relates the phage adsorption coefficient γn with the number of receptors n on the bacterium. For a small number of receptors n < n0, this relation was shown to be linear, γn ∼ n, and for a large number of receptors n > n0, γn becomes independent of n, where n0 is ∼750 based on our recent measurements (15). Thus, depending on P(0) and

is the bacterium-population-averaged phage adsorption coefficient. This behavior is consistent with Berg and Purcell's theoretical prediction, which relates the phage adsorption coefficient γn with the number of receptors n on the bacterium. For a small number of receptors n < n0, this relation was shown to be linear, γn ∼ n, and for a large number of receptors n > n0, γn becomes independent of n, where n0 is ∼750 based on our recent measurements (15). Thus, depending on P(0) and  the population will grow (Λeff > 0) or decay (Λeff < 0) in a short time. Interestingly, even for an initially decaying population, it will eventually grow in size even when the phage pressure has not been released. Because the phage pressure is still present, this intermediate- and long-time behavior can only be interpreted as a significant reduction in

the population will grow (Λeff > 0) or decay (Λeff < 0) in a short time. Interestingly, even for an initially decaying population, it will eventually grow in size even when the phage pressure has not been released. Because the phage pressure is still present, this intermediate- and long-time behavior can only be interpreted as a significant reduction in  or

or  Isolation of these persistent bacteria at a later time (∼10 h) reveals that their composition is a function of P(0). For P(0) < 1010 cm−3, the overwhelming majority of bacteria are sensitive to the λ-phage similar to the starting culture. However, for P(0) > 1010 cm−3, the population is dominated by phage-resistant mutants. This observation suggests that the persistent population cannot sustain itself; i.e., once the normal cell population (including the n = 1 subpopulation) is decimated, the persisting population cannot be replenished, and its leakage to the normal cell state will drive the persistor population to extinction if not because of the presence of the mutants. The phenomenon of bacterial coexistence with phage has a certain similarity to bacterial persistence to antibiotics (19,20). However, in the present case, phage binding sites are discrete and can be well quantified, which enables detailed experimental study and mathematical modeling.

Isolation of these persistent bacteria at a later time (∼10 h) reveals that their composition is a function of P(0). For P(0) < 1010 cm−3, the overwhelming majority of bacteria are sensitive to the λ-phage similar to the starting culture. However, for P(0) > 1010 cm−3, the population is dominated by phage-resistant mutants. This observation suggests that the persistent population cannot sustain itself; i.e., once the normal cell population (including the n = 1 subpopulation) is decimated, the persisting population cannot be replenished, and its leakage to the normal cell state will drive the persistor population to extinction if not because of the presence of the mutants. The phenomenon of bacterial coexistence with phage has a certain similarity to bacterial persistence to antibiotics (19,20). However, in the present case, phage binding sites are discrete and can be well quantified, which enables detailed experimental study and mathematical modeling.

This article is organized as follows: First, we present the experimental procedures, including bacterial cultures, λ-phage purification and labeling with fluorescent dyes, and the killing curve measurements. Here, a brief discussion of the use of fluorometry and flow cytometry for characterizing receptor distributions is also presented. The main body of the article is the Experimental Results section, which describes the measured LamB receptor distribution functions and the killing curves for E. coli strains Ymel and LE392 under different growth conditions and phage pressures. The final section is a summary of our experimental findings. For interested readers, two appendices are provided. Supplementary Material, Section A in Data S1 describes the experimental determinations of several important parameters that are required for interpreting the killing curves and for modeling the bacterium/phage population dynamics. We describe the latter in greater detail in the accompanying article referred to as Part II. In recent years, flow cytometry has played an increasingly important role in cell biology for characterizing the physiological states of cells (17,21). Section B in Data S1 provides a numerical deconvolution algorithm for extracting LamB receptor numbers in a large bacterial population. This technique is of general utility for analyzing flow cytometry data, particularly for proteins that are expressed at a minimal level.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

All of our measurements were carried out in a well-mixed liquid environment and over a relatively short period of ∼10 h. For mutant selection, some measurements were extended to ∼30 h. The simple environment and the short measurement time greatly simplify the experiment because the medium condition can be considered as constant and there is no complication from biofilm or patch formation as reported in the earlier study (2). Despite the simplicity of the experimental design, the biological phenomena we intended to study, such as the susceptibility of a bacterial population to phage pressure and the condition for bacterium/phage coexistence, are not significantly compromised by the experimental constraints. In the following sections, the important experimental procedures are described.

Bacterial and phage strains and sample preparations

To test the effect of the receptor number distribution p(n) on bacterium/phage population dynamics, two E. coli strains, Ymel (F+mel-1 supF58 λ-) and LE392 (supF58 supE44 hsdR514 galK2 galT22 metB1 trpR55 lacY1), with distinctively different p(n) values were investigated, where p(n) = Bn/B is the normalized probability density function (PDF), Bn is the bacterial subpopulation (in units of bacteria/cm3) with n functional receptors, and B = ΣBn is the total population. In various places in the article, Sn and S are used to emphasize that the bacteria under investigation are cells that are not mutants but sensitive to phage infection. As long as no phage-resistant mutants are involved, the two notations are equivalent and are interchangeable. Previously we found that for the Ymel strain, the LamB receptors are constitutively expressed (15), and p(n) is centered around  with a width of σn ≈ 150. For the LE392 strain, the lamB gene is inducible by maltose, and phage sensitivity (

with a width of σn ≈ 150. For the LE392 strain, the lamB gene is inducible by maltose, and phage sensitivity ( ) can be tuned continuously. For instance, when glucose is the sole carbon source, we found

) can be tuned continuously. For instance, when glucose is the sole carbon source, we found  and σn ≈ 2, and when maltose is the sole carbon source,

and σn ≈ 2, and when maltose is the sole carbon source,  and σn ≈ 200. A detailed description of how p(n) was determined for individual bacterial strains is given in the Experimental Results. We followed the standard protocols for bacterial culture; i.e., in all preparations, the bacteria were picked from a single colony and grown overnight in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4 w/v % (11 mM) maltose or 0.4 w/v% (22 mM) glucose. The overnight bacteria were inoculated at 1:100 into a fresh M9 medium with the proper carbon supplement and grew for another 2 h before use. At this stage the bacterial density was ∼107 cm−3. All liquid cultures were maintained at 37°C and shaken vigorously at 200 rpm.

and σn ≈ 200. A detailed description of how p(n) was determined for individual bacterial strains is given in the Experimental Results. We followed the standard protocols for bacterial culture; i.e., in all preparations, the bacteria were picked from a single colony and grown overnight in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.4 w/v % (11 mM) maltose or 0.4 w/v% (22 mM) glucose. The overnight bacteria were inoculated at 1:100 into a fresh M9 medium with the proper carbon supplement and grew for another 2 h before use. At this stage the bacterial density was ∼107 cm−3. All liquid cultures were maintained at 37°C and shaken vigorously at 200 rpm.

A common λ-phage strain (cI857+Sam7, New England Biolabs) was used in the experiment. The λ-phage were amplified in E. coli strain C190 and purified by cesium chloride density-gradient centrifugation. Because of the Sam7 mutation, the phage can be purified to very high concentrations, 1011–1013 cm−3, allowing a broad range of phage pressures to be applied to bacterial cultures. The concentrated λ-phage were dialyzed three times in the λ-dilution buffer (10 mM MgSO4, 20 mM Tris buffer, and pH 7.4) and kept at 4°C. In the population dynamic (or the killing curve) measurements, the Sam7 mutation is suppressed by the complementary amber suppressor present in both strains of the bacteria (Ymel and LE392) used in the experiment. The cI mutation, on the other hand, allows the lysogenic pathway to be blocked when the experiment is conducted at temperatures above 34°C (22). The effective blocking of the lysogenic pathway was tested by isolating lysogens at various temperatures. We found that although it is relatively easy to isolate lysogens near room temperature, in no case were lysogens identified when bacteria were grown at 37°C. Moreover, we confirmed (see Section C in Data S1) that the killing curves measurements were unaffected whether λ-cI857 or λ-vir (sus501) was used. The ease with which λ-cI857 can be purified to very high concentrations is the primary reason that all of the measurements presented herein were carried out using this phage strain.

Fluorescent tagging of LamB receptors

To characterize the receptor PDF in a bacterial population, fluorescently labeled λ-phage were used to tag LamB (1). Because of its strong affinity, λ binds to the receptor specifically with a binding constant  (cm3 s−1) for a bacterium with

(cm3 s−1) for a bacterium with  receptors (15). We closely followed the protocol provided by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) for protein labeling. Specifically, the phage were mixed with dye AlexaFluor-488 (10 mM MgSO4, 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate, pH = 8.4, 1012 phage/cm3, 2 μM dye) at room temperature for 1 h and dialyzed three times against the λ-dilution buffer to wash out nonreacted dye molecules. For the given reaction, it was found that more than 99% of phage were viable and bright enough to be seen under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, TE300) (1).

receptors (15). We closely followed the protocol provided by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) for protein labeling. Specifically, the phage were mixed with dye AlexaFluor-488 (10 mM MgSO4, 0.1 M sodium bicarbonate, pH = 8.4, 1012 phage/cm3, 2 μM dye) at room temperature for 1 h and dialyzed three times against the λ-dilution buffer to wash out nonreacted dye molecules. For the given reaction, it was found that more than 99% of phage were viable and bright enough to be seen under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, TE300) (1).

Standard phage adsorption procedures were performed to bind the λ-phage to the bacteria (15). Specifically, bacteria grown to the midexponential phase were harvested using a centrifugation technique (9000 × g for 3 min) and washed twice in a modified λ-dilution buffer (no tris). A bacterial sample with ∼107 bacteria/ml was incubated with a high concentration of fluorescent phage (∼4 × 1010 cm−3) in the λ-buffer. The reaction was kept in the dark and lasted for 40 min at 37°C. The bacteria were then washed twice by centrifugation to get rid of excess free phage. A 50-μl sample was taken and diluted into 2 ml of λ-buffer. This sample was used for the fluorometry measurement, as described below. The remainder of the sample was placed on ice in the dark until the flow cytometry was ready, typically within 2 h after labeling. At low temperatures, the infected cells in the λ-buffer do not lyse. The adsorbed phage remain bound for an extended period of time (23), allowing quantitative measurements to be performed at a later time. We found that the fluorescent histogram measured by flow cytometry does not change significantly over 24 h if the sample is put on ice and in the dark. Based on our early λ-phage adsorption experiment (15), it is reasonable to assume that each available receptor will be bound by a phage because at the phage concentration used, P(0) = 4 × 1010 cm−3, a bacterium with a single receptor has an adsorption rate of γ1 ≈ 10−13 cm3 s−1 and will be bound by a phage in ∼4 min.

Fluorometry and flow cytometry measurements

An important part of this experiment is to find the receptor PDF p(n) in a bacterial population and to correlate p(n) with the susceptibility or the killing-curve measurements. Flow cytometry is ideally well suited for such a task when the LamB receptors are fluorescently labeled. We ran the samples on two different flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson FACScan DiVa, Franklin Lakes, NJ, and Dako Cyan ADP Analyzer, Glostrup, Denmark). We found similar results on both, but the latter gave better resolution for weak signals. Despite the high brightness of labeled phage particles, which is clearly discernible in fluorescent microscopy as shown in Fig. 1 b, quantized fluorescent units for individual phage cannot be established by the flow cytometer. Thus, an intermediate calibration scheme using fluorometry (Bio-Rad VersaFluor, Hercules, CA) was introduced.

Briefly, the total fluorescent intensity (FI) for a known concentration of labeled λ-phage was determined by the fluorometer. This yields the brightness, in fluorometer units (FLU), for the given concentration of λ-phage. The same measurement was also carried out for a known concentration of bacteria that were tagged by the same fluorescently labeled λ-phage. The brightness per bacterium therefore directly gives the average number of phage bound to a bacterium. To obtain the receptor distribution, the same bacterial sample was also measured in the flow cytometer, which allows a high-throughput measurement of the FI of individual bacteria. The alignment of the average FI per bacterium obtained from both instruments allows the LamB receptor distribution to be presented on an absolute scale. Specifically, it allows the brightness of a labeled phage in the flow cytometer, called flow-cytometer unit, to be related to the FLU. To ensure consistency between different sample preparations and different instrumental settings, standard fluorescent latex beads (Interfacial Dynamics, 2-FY-1K, Portland, OR) were also used to cross calibrate the fluorometer and the flow cytometers. We used latex beads 1 μm in diameter, comparable in size to the bacterium, and with excitation and emission wavelengths identical to the AlexaFluor-488 to minimize systematic errors. In all fluorescence measurements, the excitation wavelength was set to 488 nm, and the detection was in the green channel with a center wavelength ∼530 nm. In flow cytometry measurements, the forward and the 90° scattering intensities were also used to discriminate contributions of cell debris in the fluorescence channel. The typical fluorometry and flow cytometry measurements are displayed in Fig. 2, a and c, respectively. The details of these measurements are discussed in the Experimental Results section.

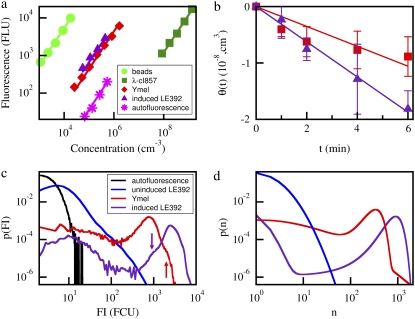

FIGURE 2.

(a) Total fluorescence readings at different dilutions were taken from samples containing phage (squares), fluorescent latex spheres (circles), Ymel + phage complexes (diamonds), induced LE392 + phage complexes (triangles), and the cell background (stars). After a background subtraction, the dilution curve was fit with a straight line with a zero intercept. These values were used to calculate the average receptor number per bacterium as shown in Table 1. (b) The phage depletion rate θ (≡ ln((P(t)/P(0))/B(0)) is measured for Ymel (squares) and for induced LE392 (triangle). The measurements were carried at 37°C in the λ-dilution buffer supplemented with 10 mM of MgSO4. The initial bacterial and phage concentrations were S(0) ≈ 108 cm−3 and P(0) ≈ 5 × 104 cm−3. As can be seen, the adsorption is more rapid with LE392 cells than with Ymel cells because of the difference in the mean receptor number. (c) The FI of different bacterial preparations was characterized by flow cytometry. The displayed curves include Ymel cells without labeling (black), uninduced LE392 with labeling (blue), Ymel with labeling (red), and induced LE392 with labeling (purple). The vertical arrows indicate secondary bumps that are often seen in the flow cytometry data. (d) After deconvolution using the cell background data, the number of phage attached to each bacterium can be calculated, and the resulting receptor PDFs are given for the uninduced LE392 (blue), the Ymel (red), and the induced LE392 (purple) bacteria. The binned PDFs are constructed based on measurements of more than 5 × 104 cells.

Killing-curve measurements and the plaque assay

The appropriate bacterial strain was grown according to the protocol discussed above. The exponentially growing bacteria were diluted 1:15 into prewarmed M9 medium, yielding an initial bacterial concentration S(0) ≈ 106 cm−3. A small aliquot was taken, and its concentration verified by colony counts on LB plates. The λ-phage were then added at a variety of concentrations 106 < P(0) < 109 cm−3, and the reaction tube was agitated on a vortex mixer briefly. A standard plaque assay was used to determine the phage concentration P(t) as a function of time. Briefly, a small sample was taken and centrifuged, and a series dilution was performed on a small sample of supernatant. The diluted sample was mixed with 500 μl of overnight Ymel in 2.5 ml of soft agar and poured onto a λ-plate (24). The plates were incubated in 37°C overnight, and the plaques on each plate were counted the next day. To measure the surviving bacterial population as a function of time, the so-called killing curve, the reaction tubes were incubated at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. At fixed time intervals, small aliquots were taken from the reaction tube, diluted in the λ-buffer, and plated onto LB plates. We found that for P(0) < 1010 cm−3 and for t ≈ 10 h, almost all colonies isolated from the agar plates are sensitive to phage infection as indicated by their plating efficiency being nearly identical to the starting parental bacteria. For this reason, the colony counts on the plate were assigned as sensitive bacterial population S(t) at time t.

EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

LamB receptor number PDFs in exponentially growing populations of E. coli

Fig. 2 a displays a series of fluorometry measurements. Here, the total FI is plotted against the concentrations of fluorescently labeled λ-phage (squares), Ymel labeled with the λ-phage (diamonds), LE392 labeled with the λ-phage (triangles), LE392 with no labeling (stars), and fluorescent beads (circles). In all the measurements, the concentrations covered more than one decade, and a good linear relation between the total fluorescence and the concentration was found. The slopes of the curves, after the subtraction of the background (stars) yield the average FLU per concentration. Because the measurement volume was fixed for all runs, the ratio of the measured slopes between bacterial and phage samples gives the average number of phage (or receptors,  ) per bacterium. For the two bacterial strains, we found

) per bacterium. For the two bacterial strains, we found  for Ymel and

for Ymel and  for induced LE392. These results are tabulated in Table 1. We note that the measured

for induced LE392. These results are tabulated in Table 1. We note that the measured  is far below the upper limit of close packing of phage on the cell surface, which we estimated to be 2800 for Ymel and 3600 for LE392. These numbers are consistent with the estimate made in earlier phage/bacteria studies (25). However, the steric effect is expected to appear below the maximum numbers estimated above and could potentially skew the PDF measurement for bacteria with very large n.

is far below the upper limit of close packing of phage on the cell surface, which we estimated to be 2800 for Ymel and 3600 for LE392. These numbers are consistent with the estimate made in earlier phage/bacteria studies (25). However, the steric effect is expected to appear below the maximum numbers estimated above and could potentially skew the PDF measurement for bacteria with very large n.

TABLE 1.

Parameters for phage adsorption and reproduction

| Constant | Description | Ymel | LE392 |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (μm) | Semimajor axis | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| b (μm) | Semiminor axis | 0.46 | 0.48 |

| γ∞ (cm3/s) | Maximum adsorption rate | 9.1 × 10−11 | 1.1 × 10−10 |

| Λ (1/h) | Growth rate | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| m | Bursting coefficient | 14 | 12 |

| τ (min) | Latent period | 47 | 45 |

|

Average receptor number (fluorometry) | 270 ± 30 | 550 ± 80 |

|

Average receptor number (flow cytometry) | 240 ± 30 | 570 ± 50 |

| σn | Standard deviation of p(n) (flow cytometry) | 140 ± 60 | 200 ± 10 |

This table contains the relevant parameters for E. coli strains Ymel and LE392, and phage λ−cI857 used in this experiment. The quoted uncertainties are standard errors of the mean. These listed parameters are used in all fits and calculations in Part II.

Using the mean receptor numbers  obtained from fluorometry, we can determine the receptor distribution p(n) from flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2 c, a noticeable feature of the flow cytometry data is that FI spreads over a broad range, implying that p(n) would be similarly broad. We also noticed that even for unlabeled bacteria, the background fluorescence (black) contributes to the measurement, making the correction to this background necessary. In Section B in Data S1, a deconvolution algorithm is presented that allows us to extract p(n) from the fluorescent histogram. We found that although the background correction is small for large n, which is equivalent to a shift in the FI, the deconvolution procedure is quantitatively significant for cell subpopulations with small n. This is especially the case for uninduced LE392 bacteria (blue), which on average have

obtained from fluorometry, we can determine the receptor distribution p(n) from flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2 c, a noticeable feature of the flow cytometry data is that FI spreads over a broad range, implying that p(n) would be similarly broad. We also noticed that even for unlabeled bacteria, the background fluorescence (black) contributes to the measurement, making the correction to this background necessary. In Section B in Data S1, a deconvolution algorithm is presented that allows us to extract p(n) from the fluorescent histogram. We found that although the background correction is small for large n, which is equivalent to a shift in the FI, the deconvolution procedure is quantitatively significant for cell subpopulations with small n. This is especially the case for uninduced LE392 bacteria (blue), which on average have  Fig. 2 d displays p(n) for uninduced/labeled LE392 (blue), labeled Ymel (red), and induced/labeled LE392 (purple). Here, the total number of cells in each data set is ∼105, and FI is distributed in equally spaced bins.

Fig. 2 d displays p(n) for uninduced/labeled LE392 (blue), labeled Ymel (red), and induced/labeled LE392 (purple). Here, the total number of cells in each data set is ∼105, and FI is distributed in equally spaced bins.

The above measurements have established that  can change by orders of magnitude, depending on bacterial strains and preparations. For instance, on average, uninduced LE392 bacteria have

can change by orders of magnitude, depending on bacterial strains and preparations. For instance, on average, uninduced LE392 bacteria have  whereas induced LE392 bacteria have

whereas induced LE392 bacteria have  Unlike LE392, Ymel always yields

Unlike LE392, Ymel always yields  of a few hundred that do not depend strongly on the growth medium or induction (15). Measurements were also performed on LE392 grown in glycerol (data not shown). In this case, large fluctuations in

of a few hundred that do not depend strongly on the growth medium or induction (15). Measurements were also performed on LE392 grown in glycerol (data not shown). In this case, large fluctuations in  were observed from run to run, with

were observed from run to run, with  varying between 10 and ∼100. We also noticed that when lamB is expressed at very low levels, such as uninduced LE392, the receptor PDF has a single peak, and the functional form of p(n) can be mimicked very well by a log-normal distribution, which facilitates the deconvolution as will be shown in Section B in Data S1. On the other hand, when lamB is expressed at high levels, p(n) is bimodal and consists of a major peak at nmax and a minor peak at n′max. In this case, we found nmax ≈ 250 for Ymel and ∼600 for induced LE392, and n′max ≈ 0 for both strains as delineated in Fig. 2 d. Some secondary maxima or bumps were often observed in the raw data as in Fig. 2 c, but these fine structures disappear after deconvolution. The bimodal distribution of protein expression is not unique to the LamB protein but is akin to the expression pattern of LacZ in wild-type bacteria when a trace amount of lactose is present. The phenomenon can be understood as a result of an autocatalytic effect of the inducer on the lac operon (26). However, in this case, the bimodal distribution is hard to understand because previous studies have shown that, at the maltose concentration used in our experiment, the transport of the sugar molecules into cells does not require the presence of LamB (27). Thus, the autocatalytic effect, although appealing, may not be used to explain the bimodal distribution of LamB in the highly induced cell populations.

varying between 10 and ∼100. We also noticed that when lamB is expressed at very low levels, such as uninduced LE392, the receptor PDF has a single peak, and the functional form of p(n) can be mimicked very well by a log-normal distribution, which facilitates the deconvolution as will be shown in Section B in Data S1. On the other hand, when lamB is expressed at high levels, p(n) is bimodal and consists of a major peak at nmax and a minor peak at n′max. In this case, we found nmax ≈ 250 for Ymel and ∼600 for induced LE392, and n′max ≈ 0 for both strains as delineated in Fig. 2 d. Some secondary maxima or bumps were often observed in the raw data as in Fig. 2 c, but these fine structures disappear after deconvolution. The bimodal distribution of protein expression is not unique to the LamB protein but is akin to the expression pattern of LacZ in wild-type bacteria when a trace amount of lactose is present. The phenomenon can be understood as a result of an autocatalytic effect of the inducer on the lac operon (26). However, in this case, the bimodal distribution is hard to understand because previous studies have shown that, at the maltose concentration used in our experiment, the transport of the sugar molecules into cells does not require the presence of LamB (27). Thus, the autocatalytic effect, although appealing, may not be used to explain the bimodal distribution of LamB in the highly induced cell populations.

Based on the model of Berg and Purcell (14), it is evident that induced LE392 bacteria should be more susceptible to phage infection than Ymel or uninduced LE392 because LamB is expressed at a higher level. However, under a large phage pressure or over a long time, the fitness of the bacterial population depends not only on the average number of receptors  but also on the spread or the standard deviation σn of the distribution p(n). Most importantly it also depends on the size of the minority population with

but also on the spread or the standard deviation σn of the distribution p(n). Most importantly it also depends on the size of the minority population with  close to zero. Unfortunately, our current measurements do not allow us to distinguish a single bound fluorescent phage unambiguously from the cell's background fluorescence; our detection limit in the best case is ∼2 fluorescent phages as judged by the width of the autofluorescence PDF in Fig. 2 c. Using this criterion, we found that the minority population (

close to zero. Unfortunately, our current measurements do not allow us to distinguish a single bound fluorescent phage unambiguously from the cell's background fluorescence; our detection limit in the best case is ∼2 fluorescent phages as judged by the width of the autofluorescence PDF in Fig. 2 c. Using this criterion, we found that the minority population ( ) for induced LE392 is less than 0.7% of the total population; it is less than 2% for Ymel; it is between 2% and 10% for LE392 grown in glycerol; and ∼20% of bacteria have no receptor (n = 0) for uninduced LE392. For convenience, the mean

) for induced LE392 is less than 0.7% of the total population; it is less than 2% for Ymel; it is between 2% and 10% for LE392 grown in glycerol; and ∼20% of bacteria have no receptor (n = 0) for uninduced LE392. For convenience, the mean  and its standard deviation σn for different bacterial preparations are given in Table 2.

and its standard deviation σn for different bacterial preparations are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Mean and standard deviation of p(n)

| LE392 (glucose) | LE392 (glycerol) | LE392 (glycerol) | LE392 (maltose) | Ymel (glucose) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2 | 20 | 100 | 570 | 240 |

| σn | 2 | 25 | 75 | 200 | 140 |

Receptor-number statistics for Ymel and LE392 in different growth media. Large variations were observed for LE392 in glycerol, and two typical runs are tabulated.

Phage adsorption rate for different bacteria

Measurements were carried out to characterize phage adsorption rates for Ymel and induced LE392 bacteria in the λ-buffer containing 10 mM MgSO4. We followed the protocol used in our earlier study (also see Section A in Data S1) (15). Briefly, the bacteria and phage were mixed at t = 0 with a very small multiplicity of infection (MOI ≡ P(0)/S(0)) ∼10−3. The small MOI ensures single phage attachments for infected bacteria, allowing a quantitative modeling of the adsorption process (15). The free phage P(t) in the reaction volume was sampled periodically and plated on λ-plates. For early times, P(t)/P(0) was found to decrease approximately in an exponential fashion, and depletion of the free phage in the sample was found to obey the second-order reaction law:  This quantity is plotted in Fig. 2 b for both strains of bacteria. The slopes of these curves are the phage adsorption coefficients

This quantity is plotted in Fig. 2 b for both strains of bacteria. The slopes of these curves are the phage adsorption coefficients  which can be related to the average number of receptors

which can be related to the average number of receptors  on the bacteria. We observed that induced LE392 bacteria (squares) decay faster than Ymel bacteria (diamonds), which is expected because the former expresses more receptors.

on the bacteria. We observed that induced LE392 bacteria (squares) decay faster than Ymel bacteria (diamonds), which is expected because the former expresses more receptors.

According to Berg and Purcell (14), the phage adsorption rate γn for a bacterium having n receptors is given by γn = γ∞C(n), where γ∞ is the adsorption rate for a bacterium fully covered with receptors, and C(n) = ns/(ns + aπ/ln(2a/b)). Here a and b are, respectively, the semimajor and the semiminor axes of the cell, and s is the radius of the receptors. For adsorption taking place within the first 10 min, the phage uptake is determined by the average behavior of the cell population, so that  The maximum adsorption rate for an ellipsoid-shaped bacterium is given by

The maximum adsorption rate for an ellipsoid-shaped bacterium is given by  (14), where D is the diffusion coefficient of the λ-phage. We determined D using quasielastic light scattering (15) and found D = 7.6 × 10−8 cm2/s at 37°C, which compared favorably with the Stokes-Einstein relation,

(14), where D is the diffusion coefficient of the λ-phage. We determined D using quasielastic light scattering (15) and found D = 7.6 × 10−8 cm2/s at 37°C, which compared favorably with the Stokes-Einstein relation,  for a sphere of radius R = 35 nm. Here kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and η is the viscosity of the fluid. We noticed that R measured by light scattering is slightly larger (∼15%) when compared with the λ capsid determined by electron microscopy. From x-ray data for LamB receptors, which yield s = 4 nm (28), and the measured a and b as reported in Section A in Data S1, γ∞ was found to be 9.1 × 10−11 cm3/s for Ymel and 1.1 × 10−10 cm3/s for LE392. For a small number of receptors, n < n0 (≡ aπ/s ln(2a/b)) ≈ 750 for Ymel (or 860 for LE392), C(n) is linear in n, yielding γn = γ1n, where γ1 = 4Ds = 1.2 × 10−13 cm3/s is the adsorption rate for a single receptor on a bacterium. The above theoretical prediction allowed us to extract

for a sphere of radius R = 35 nm. Here kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, and η is the viscosity of the fluid. We noticed that R measured by light scattering is slightly larger (∼15%) when compared with the λ capsid determined by electron microscopy. From x-ray data for LamB receptors, which yield s = 4 nm (28), and the measured a and b as reported in Section A in Data S1, γ∞ was found to be 9.1 × 10−11 cm3/s for Ymel and 1.1 × 10−10 cm3/s for LE392. For a small number of receptors, n < n0 (≡ aπ/s ln(2a/b)) ≈ 750 for Ymel (or 860 for LE392), C(n) is linear in n, yielding γn = γ1n, where γ1 = 4Ds = 1.2 × 10−13 cm3/s is the adsorption rate for a single receptor on a bacterium. The above theoretical prediction allowed us to extract  using the adsorption curve in Fig. 2 b. For instance, using the measured adsorption coefficient

using the adsorption curve in Fig. 2 b. For instance, using the measured adsorption coefficient  cm3s−1 for Ymel, we found

cm3s−1 for Ymel, we found  whereas using

whereas using  cm3s−1 for LE392, we found

cm3s−1 for LE392, we found  These measurements are reasonably consistent with the same quantity obtained from the flow cytometry measurements and with our previous studies (1,15).

These measurements are reasonably consistent with the same quantity obtained from the flow cytometry measurements and with our previous studies (1,15).

Susceptibility of bacteria to phage infection: the killing curves

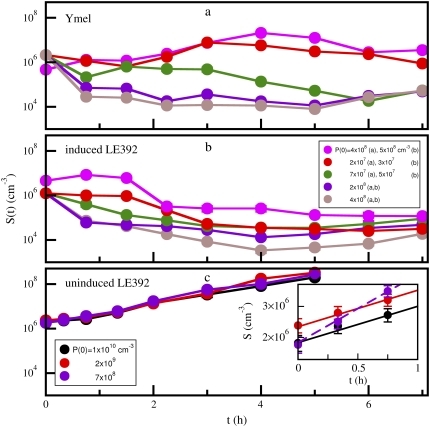

To measure the response of a bacterial population to a phage attack, the exponentially growing bacteria with concentration S(0) ≈ 106 cm−3 was subject to infection with different initial phage concentrations P(0). The MOI was varied by more than two orders of magnitude ranging from ∼1 to ∼500. The bacteria that survived the phage attack at time t were titered on LB plates. Fig. 3 a shows the killing curves for Ymel. Here, a range of behaviors was observed as P(0) increases. For P(0) < 4 × 106 cm−3, we found that the bacterial population S(t) always grows exponentially in early times. As indicated by the run with the lowest P(0) (4 × 106 cm−3, pink) displayed in the figure, S(t) increases for the first 4 h with an effective growth rate of Λeff ≈ 0.99 h−1 and then it decreases for t > 4 h. We note that Λeff is only slightly lower than the normal growth rate Λ = 1.1 h−1 when the phage pressure is absent. The decreasing S(t) in the later time results from amplification of phage in the medium, which causes the phage pressure to rise. A moderate increase in the phage pressure P(0) (2 × 107 cm−3, red) causes S(t) to decrease momentarily, but after 2 h it recovers. In general, the bacterial response is highly nonlinear. Further increasing P(0) (7 × 107 cm−3, green, purple, and brown) causes S(t) to decline initially, and the rate of decrease is proportional to P(0). We also noticed that when a large P(0) (such as 2 × 108 cm−3, purple, or 4 × 108 cm−3, brown) is imposed, S(t) lapses into a long period of refractory phase with no net growth for 1 < t < 6 h, and S(t) then begins to increase exponentially 6 h after the initial killing.

FIGURE 3.

The response of Ymel (a), induced LE392 (b), and uninduced LE392 (c) bacterial populations to perturbations by different phage pressures P(0). The phage concentrations, P(0), for runs in a and b are similar for the corresponding colors, and the detail numbers are given in the legend of b. The phage concentrations for runs in c are also given in the legend of the figure. For both bacterial strains in a and b, three different initial responses were observed, corresponding to growing, decaying, or having a zero growth rate. After killing with a high P(0), the subsequent bacterial growth rate is often very low immediately after killing and persists for several hours. Exponential growth (not displayed) is always observed in long times. As shown in c, the uninduced LE392 cells are much less affected by increasing P(0). A close inspection of the earlier data, which are displayed in the inset, the growth rates for the two highest P(0) = 2 × 109 cm−3 (red) and 1010 cm−3 (black) are nearly identical.

The killing curves for LE392 depend strongly on whether the cells are induced or uninduced by maltose. As shown in Fig. 3 b, the induced LE392 cells are more susceptible to phage infection than Ymel cells as indicated by the faster initial killing and the smaller surviving population for a comparable P(0). This is consistent with the observation that LE392 has a higher  than Ymel. The response of uninduced LE392 cells to phage pressure is very different, as delineated in Fig. 3 c. Here, three different P(0) levels (7 × 108, purple; 2 × 109, red; and 1 × 1010 cm−3, black) were used, and in all cases, the initial growth rate Λeff was positive, indicating that the bacterial growth rate outweighs the killing rate. However, a careful inspection of the early data, which are replotted in the inset, reveals that the growth is not purely exponential (a finding that is further analyzed in Part II), and the growth rate for P(0) = 7 × 108 cm−3 is faster than those for higher phage pressures. We also noticed that for P(0) ≥ 2 × 109 cm−3, the initial killing curves (the red and the black lines) are independent of P(0), suggesting that bacteria with n > 0 are decimated. Thus, these curves represent the intrinsic growth dynamics of the n = 0 subpopulation that is not directly affected by the phage pressure. Measurements using LE392 cells grown in glycerol and exposed to a range of phage pressure 3 × 107 < P(0) < 7 × 108 cm−3 showed phage sensitivity in between the uninduced LE392 cells and the Ymel cells, as expected. In some experiments, we frequently sampled the bacterial concentration along with the phage concentration as for the killing curve.

than Ymel. The response of uninduced LE392 cells to phage pressure is very different, as delineated in Fig. 3 c. Here, three different P(0) levels (7 × 108, purple; 2 × 109, red; and 1 × 1010 cm−3, black) were used, and in all cases, the initial growth rate Λeff was positive, indicating that the bacterial growth rate outweighs the killing rate. However, a careful inspection of the early data, which are replotted in the inset, reveals that the growth is not purely exponential (a finding that is further analyzed in Part II), and the growth rate for P(0) = 7 × 108 cm−3 is faster than those for higher phage pressures. We also noticed that for P(0) ≥ 2 × 109 cm−3, the initial killing curves (the red and the black lines) are independent of P(0), suggesting that bacteria with n > 0 are decimated. Thus, these curves represent the intrinsic growth dynamics of the n = 0 subpopulation that is not directly affected by the phage pressure. Measurements using LE392 cells grown in glycerol and exposed to a range of phage pressure 3 × 107 < P(0) < 7 × 108 cm−3 showed phage sensitivity in between the uninduced LE392 cells and the Ymel cells, as expected. In some experiments, we frequently sampled the bacterial concentration along with the phage concentration as for the killing curve.

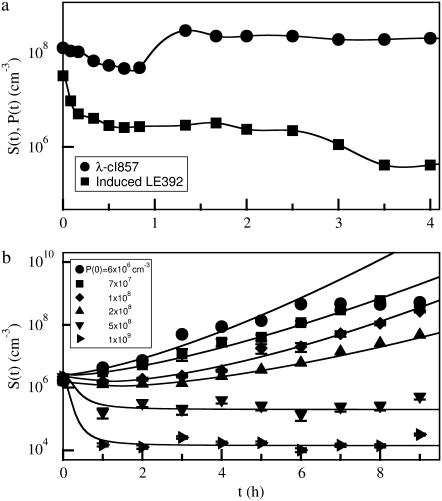

In the above discussion, we have left out the temporal fluctuations of phage concentration P(t) over time. These fluctuations are most noticeable when the condition P(0) ≫  S(0) is not satisfied, i.e., when P(0) becomes comparable to or less than S(0). Fig. 4 a depicts a run where we have followed simultaneously the concentrations of bacteria S(t) (squares) and the phage P(t) (circles) over a period of 4 h. The measurement was carried out with LE392 at the initial concentration of S(0) = 3 × 107 cm−3 and the phage concentration P(0) = 108 cm−3. Both species were sampled periodically at a relatively high frequency, particularly at early times. The phage concentration was determined using serial dilutions and the plaque assay (15). We observed that more than 90% of bacteria were decimated within the first 30 min, and because MOI was only 3, the phage concentration slowly declined as a result of phage adsorption. However, once the bacteria started to burst, releasing a large crop of phage particles, which occurred at t = 1 h, the phage concentration suddenly jumped to a high level ∼2 × 108 cm−3. At this point the MOI also increased and was of the order of 100. Because the surviving bacteria typically have fewer receptors, the condition P(0) ≫

S(0) is not satisfied, i.e., when P(0) becomes comparable to or less than S(0). Fig. 4 a depicts a run where we have followed simultaneously the concentrations of bacteria S(t) (squares) and the phage P(t) (circles) over a period of 4 h. The measurement was carried out with LE392 at the initial concentration of S(0) = 3 × 107 cm−3 and the phage concentration P(0) = 108 cm−3. Both species were sampled periodically at a relatively high frequency, particularly at early times. The phage concentration was determined using serial dilutions and the plaque assay (15). We observed that more than 90% of bacteria were decimated within the first 30 min, and because MOI was only 3, the phage concentration slowly declined as a result of phage adsorption. However, once the bacteria started to burst, releasing a large crop of phage particles, which occurred at t = 1 h, the phage concentration suddenly jumped to a high level ∼2 × 108 cm−3. At this point the MOI also increased and was of the order of 100. Because the surviving bacteria typically have fewer receptors, the condition P(0) ≫  S(0) is now satisfied. Indeed, as we observed in Fig. 4 a, P(t) remains constant for t > 1.5 h.

S(0) is now satisfied. Indeed, as we observed in Fig. 4 a, P(t) remains constant for t > 1.5 h.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Simultaneous measurements of bacterial (LE392) and phage concentrations as a function of time. Here the initial MOI = 3 is low so that the phage concentration decreases with time. However, the combination of killing of the bacteria and reproduction of phage at t = 1 h significantly increases MOI to ∼100. The net result is that the constant-P assumption is satisfied for t > 1.5 h as shown. (b) Killing curves in a reduced-magnesium-salt medium. To determine whether the initial adsorption is responsible for the observed killing curves, the measurements were also conducted with Ymel in the λ-buffer with reduced MgSO4 (1 mM instead of 10 mM). In the reduced-salt medium, the phage adsorption rate was decreased by a factor of four. The bacterial concentration was S(0) = 2 × 106 cm−3. A range of phage concentrations was used, and they are labeled in the figure. The solid lines are a guide to the eye.

If the above observed dynamic behaviors were determined by the first stage of infection, i.e., the binding of a virus to a receptor, it would be useful to alter the binding affinity between the phage and receptors and to study how S(t) responds under such a situation. Earlier experiments indicated that the ability of a phage to bind to a receptor depends strongly on the ion concentration in the medium (15). Such dependence suggests that electrostatic interaction plays a role in facilitating the recognition and binding of phage to receptors. Killing curves were therefore measured in M9 medium where the MgSO4 salt concentration was reduced from the original 10 mM to 1 mM. Following the same experimental procedures as above, measurements were performed on Ymel bacteria, and the data are displayed in Fig. 4 b. One observes that the response of S(t) to phage pressure is more systematic under this condition. For small P(0) ≈ 6 × 106 cm−3, S(t) increases with time, giving rise to a positive effective growth rate Λeff. On the other hand, when P(0) passes a threshold of ∼2 × 108 cm−3, S(t) decreases with time, giving rise to a negative effective growth rate Λeff < 0. Unlike in the high-salt condition, the bacterial population here evolves more smoothly. This may be because of the low infection rate, which causes P(t) to evolve smoothly rather than to fluctuate widely as seen in the high-salt medium.

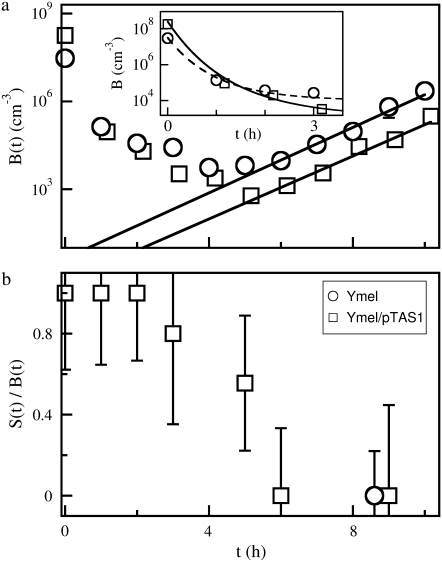

The sensitivity to phage infection can also be altered in the opposite direction by transforming bacteria with a plasmid that expresses LamB. A high-copy-number plasmid pTAS1 (a gift of J. Lawrence), which confers ampicillin resistance and expresses LamB constitutively, was used for this part of the measurements. The data are displayed in Fig. 5 a, which shows that bacteria Ymel (circles) and Ymel/pTAS1 (squares) respond to the phage pressure in the same fashion; their numbers decay rapidly initially and then level off. Overall, the bacteria Ymel/pTAS1 are decimated more rapidly than Ymel and reach a minimum that is about two orders of magnitude lower than that of Ymel. Note that the starting concentration S(0) of Ymel/pTAS1 is about four times higher than that of Ymel. This observation is again consistent with the fact that Ymel/pTAS1 expresses LamB at a higher level than Ymel cells. The above measurements leave little doubt that the receptor expression level and the binding affinity are the determinant factors of susceptibility of a bacterium to phage infection, and they can be altered by various experimental means.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Killing curves with high phage concentrations. The measurements were carried out with P(0) = 4 × 1010 cm−3. Two different bacteria, Ymel (circles) and Ymel + pTAS1 (squares), were used. To have significant colony counts, the bacterial concentration B(0) was increased (3 × 107 and 2 × 108 cm−3) in this set of measurements. The cells with the plasmid showed a slightly faster killing and a lower level of survival bacteria at long times. The inset delineates in more detail the earlier killing behavior. After ∼5 h both cells begin to grow exponentially, as indicated by the straight lines. The low intercept values at t = 0 indicate possible contributions by mutants. (b) The cells were tested for their sensitivity to phage infection. After ∼6 h, the fraction of sensitive cells, S(t), diminishes in the total cell population, B(t). Here squares are for Ymel + pTAS1, and the circle is for Ymel.

Bacterial composition at late times

Runs such as those displayed in Fig. 3 have been repeated several times, and the general features of the data are reproducible. In particular, the recovery of the bacterial population at long times was observed for all runs. Bacterial resistance to phage infection can arise for a range of reasons such as mutants that lack necessary proteins to synthesize the virus or the emergence of lysogens that bypass the lytic cycle (29). These possibilities were ruled out by testing the bacterium's sensitivity to λ-phage after they were regrown in a phage-free environment for ∼30 generations. Specifically, small samples were taken at different hours in the late period. The cells were washed using the λ-buffer and centrifugation and then plated on LB plates. The washed bacteria grew normally on the agar plates, and their sensitivity to λ was tested using the plaque assay (24). We found that most colonies isolated in this fashion were able to form plaques, indicating that they have recovered the ability to bind λ-phage and are λ sensitive. Moreover, our recent measurements also indicate that surviving cells that form plaques have a receptor distribution p(n) that is nearly identical to their parental cells (30).

Can phage-resistant mutants be selected in a reasonable time in our experiment? This question was answered by the killing curve (circles) presented in Fig. 5 a, where an exponentially growing Ymel population was exposed to a very high phage pressure of P(0) = 4 × 1010 cm−3 and a relatively large initial bacterial population, B(0) ≈ 4 × 107 cm−3. The surviving bacteria were sampled at a regular interval of ∼1 h. As shown in the figure, there is a rapid initial killing, more than a factor of 102 in the first hour, and it is followed by a slow killing over the next 4 h. The effective growth rate Λeff in this period is negative, and its magnitude is similar to Λ. Over this entire period (0 < t < 5 h), B(t) decreases by a factor of 104, which is a bigger decline compared with those killing curves measured with relatively lower phage pressures shown in Fig. 3. After 5 h, the bacterial population begins to recover. One observes that the recovery is exponential with the rate Λeff ≈ 1.25 h−1 that is comparable to the bacterial growth rate Λ without the phage pressure. Most of the bacteria isolated after 9 h and regrown for ∼35 generations under the phage-free condition failed the plaque-assay test. We take this as the indication that these bacteria are phage-resistant “mutants.”

If the late-time killing data were fit to an exponential function, a straightforward extrapolation to t = 0 indicates that the initial Ymel population (∼4 × 107 cm−3) contained ∼4 ± 3 “mutants,” suggesting that in a large population, the probability of finding a mutant is ∼10−7. This measurement was repeated four times, and the result appears to be rather reproducible. Our measurements show that the phage-resistant mutation rate in our experiment is ∼10 times greater than that reported in the classical experiment of Luria and Delbruck (31) who found 2.5 × 10−8 per division time for phage T1. The rarity that phage-resistant mutants were selected in our killing-curve measurements, such as those displayed in Fig. 3 a, can be understood as a result of our relatively small sample size, B(0) ≈ 106 cm.−3 For moderate phage pressures, P(0) ≈ 108–109, the surviving bacterial population is ∼104 cm−3 or less as delineated in Fig. 3, a and b. Under such a condition, there will be ∼10% chance that a phage-resistant mutant will be introduced in the initial population. This probability will be reduced to ∼1% if one uses the mutation rate determined in the classical Luria-Delbruck experiment. If a mutant is introduced in the initial culture, how long does it take to reproduce to the level that becomes noticeable in the measurement? A simple back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that to reach a population size of 105 cm−3, it would take ∼10 h, which is longer than our typical measurements, and by then, the mutant population would be overwhelmed by the persistor population. This simple estimate suggests that neither mutants introduced in the starting culture nor spontaneous mutations during the measurement contribute noticeably in our killing-curve measurements, which typically last for 6–8 h.

To see how mutant selection depends on the rate of λ receptor synthesis, the killing curve was repeated for Ymel/pTAS1, which constitutively expresses LamB and is under the selection pressure of ampicillin. We used B(0) ≈ 3 × 108 cm−3 to increase the chance that mutant bacteria could be isolated, and P(0) remained at 4 × 1010 cm−3. The data from this measurement are plotted as squares in Fig. 5 a. Comparing with the killing curve for Ymel without the plasmid (circles), we found that the initial killing for Ymel/pTAS1 is more rapid with >99.9% cells decimated within the first hour, indicating that overall, more receptors were produced in the cell population. In the slow-killing period (1 < t < 5 h), which we believe reflects the population dynamics of n = 0 subpopulation, Ymel/pTAS1 cells appear to decrease in number only marginally faster than Ymel despite the high copy numbers of plasmids and correspondingly high mRNA transcripts. To test the phage sensitivity of the Ymel/pTAS1 cells, 10 colonies from each selected time point on the killing curve were regrown and tested for their ability to form plaques on soft agar plates. Fig. 5 b (squares) shows the percentage of colonies that form plaques as a function of time, where the vertical axis represents the ratio of the number of sensitive cells, which should be proportional to S(t), and the total number of cells tested, which should be proportional to B(t). Initially (0 < t < 2 h), all cells tested were sensitive, but the percentage start to decrease significantly after 5 h. Beyond 6 h most colonies tested were λ resistant or “mutants” by our definition. We note that the 6-h time mark coincides well with the killing curve where B(t) reaches its minimum and begins to recover exponentially. Seventeen Ymel colonies (no plasmid) were also tested for phage sensitivity at 9 h (Fig. 5 b, circle), but none of these colonies showed phage sensitivity. Using flow cytometry, we found that these phage-resistant “mutants,” both with and without pTAS1, were strongly heterogeneous in their LamB expression with  ranging from a few to ∼60. The average number of receptors in all six trials was

ranging from a few to ∼60. The average number of receptors in all six trials was  These bacteria were not lysogens because they could not be infected with either λ-cI857 or λ-vir. Examples of measured receptor distributions of “mutants” are presented in Fig. S1 D in Data S1.

These bacteria were not lysogens because they could not be infected with either λ-cI857 or λ-vir. Examples of measured receptor distributions of “mutants” are presented in Fig. S1 D in Data S1.

The above observations allow several conclusions to be made: 1), Phage-resistant “mutants” can be selected in a short time of ∼6 h when a very high phage pressure, P(0) > 1010 cm−3, and a relatively large initial bacterial population, B(0) ≈ 107–108 cm−3, are present. The large P(0) ensures that any bacterium with a finite number of receptors is eliminated faster than it can reproduce. 2), Based on our measured phage adsorption rate, the slow-killing period may be interpreted as a result of switching of bacteria from n = 0 to n ≠ 0 states. With the population dynamic equations for a heterogeneous population developed in Part II, the n = 0 population can be modeled simply as dS0/dt = ΛeffS0 if the bacteria were killed instantly after switching, where S0 is the sensitive bacterial subpopulation with n = 0 and  with αm0 being the switching rate from n = 0 to n = m state. For Λeff ≈ −Λ as observed in Fig. 5 a, we found that the total switching rate from n = 0 state to other states is about twice the native bacterial growth rate Λ; i.e.,

with αm0 being the switching rate from n = 0 to n = m state. For Λeff ≈ −Λ as observed in Fig. 5 a, we found that the total switching rate from n = 0 state to other states is about twice the native bacterial growth rate Λ; i.e.,  It should be noted that this switching rate is for fully induced LE392 bacteria. In comparison, for uninduced LE392 bacteria and under a similarly high phage pressure (P(0) = 1 × 1010 cm−3, black) as displayed in Fig. 3 c, Λeff is always positive, suggesting that the total switching rate

It should be noted that this switching rate is for fully induced LE392 bacteria. In comparison, for uninduced LE392 bacteria and under a similarly high phage pressure (P(0) = 1 × 1010 cm−3, black) as displayed in Fig. 3 c, Λeff is always positive, suggesting that the total switching rate  is considerably slower in this case. Thus, the net switching rate of the n = 0 subpopulation can be influenced by the environment. 3), Because with the plasmid encoding the lamB gene, about a factor of 10 more bacteria were killed than for Ymel without the plasmid, it can be concluded that most phage-resistant “mutants” in Ymel are defective in their receptors or in the receptor expression pathway rather than in other phage-infection-related host genes. This appears to be a rather well recognized fact in the phage research community (7,18), and it simplifies considerably our investigation because we need to focus only on expression of one protein, the LamB.

is considerably slower in this case. Thus, the net switching rate of the n = 0 subpopulation can be influenced by the environment. 3), Because with the plasmid encoding the lamB gene, about a factor of 10 more bacteria were killed than for Ymel without the plasmid, it can be concluded that most phage-resistant “mutants” in Ymel are defective in their receptors or in the receptor expression pathway rather than in other phage-infection-related host genes. This appears to be a rather well recognized fact in the phage research community (7,18), and it simplifies considerably our investigation because we need to focus only on expression of one protein, the LamB.

As will be shown in Part II, the heterogeneous model predicts that to kill all sensitive bacteria, the phage concentration must be large enough that the killing rate for bacteria with only a single receptor is greater than their growth rate, or in short, γ1P(0) > Λ. In addition, the phage concentration has to be greater than the total number of receptors per volume or  These two conditions differ in that the former is the kinetic requirement, whereas the latter ensures that there are enough phage particles to bind to all receptors, including bacteria with only one receptor. It is interesting that this prediction appears to be well supported by our mutant selection experiments.

These two conditions differ in that the former is the kinetic requirement, whereas the latter ensures that there are enough phage particles to bind to all receptors, including bacteria with only one receptor. It is interesting that this prediction appears to be well supported by our mutant selection experiments.

CONCLUSION

The current experiment strives to clarify the surprising and biologically significant finding that in a closed and well-mixed environment, bacteria can coexist with antagonistic viruses over a broad range of phage pressures. After many generations, the surviving bacteria were found not to be mutants, as one might suspect, but to display phage sensitivity similar to their parental cells when regrown in a phage-free environment. The ability of a bacterial population to cope with phage stress can be varied by changing the affinity of phage adsorption and the level of receptor expression. There have been a few similar studies (2,3,7), and long-term survival of sensitive bacteria has been discussed using a variety of mechanisms (7). In this article, we provide experimental evidence in support of the notion that heterogeneous (LamB) protein expression, which creates cells with varying degrees of phage sensitivity, is largely responsible for the coexistence of bacteria and phage in a well-mixed culture. Further support for this notion is provided by the theoretical analysis in the follow-up article, Part II, where it is shown that a heterogeneous cell population is more robust than a homogeneous population when it encounters a phage stress. The improved fitness results from the fact that in the presence of phage, the high-receptor-number cells are preferentially infected, and they also effectively shield low-receptor-number cells from phage attack, allowing the latter population to grow despite the phage pressure. The low-receptor-number population survives the phage attack in part because of its intrinsic low phage sensitivity and in part from the low rate of LamB synthesis by this population.

As for most biological interactions, a benefit is usually associated with a cost. This cost usually reflects an individual's growth rate. In this case, it is the inefficient transport of large hydrocarbon molecules, maltose and maltodextrin, into the cell to be utilized as carbon sources. The bacteria with low numbers of LamB receptors are unable to grow normally in a maltose-limited environment. However, apparently, such a cost is well offset by a much lowered susceptibility to phage infection. Interestingly, we found that even in fully induced cultures, a significant number of bacteria (∼1%) are still maintained at a low-receptor-number state. Our data strongly suggest that under phage pressure, the bacteria undergo a simple cell-state selection before a genetic selection. In other words, the protein expression heterogeneity delays and increases the threshold of population extinction, gaining valuable time for genetic selection. These observations have broad implications for bacterium/phage population dynamics and for the modeling of biological evolution.

Our experiment leaves many important issues unanswered. Among them, the most significant is the fundamental mechanism that creates population heterogeneity. It is unknown whether such population diversity is an intrinsic property of stochastic gene expression or is a part of the program in the bacterium's life cycle. Specifically, it raises interesting questions about signal transduction and noise propagation in the maltose regulon (32,33), which, despite its important biological function, is much less well understood than other metabolic systems such as the lac or ara operon (26,34). Current work has only marginally addressed the issue of phenotype switching rate, an important kinetic parameter in the experiment. Our preliminary result suggests that the switching rate is a function of phage pressure, implying that switching depends on the state of a cell. In particular, it appears that for the low-receptor-number cells, the leaking time to normal cell population is comparable to or slightly faster than the bacterial growth rate Λ when the regulon is fully induced. However, the switching rate for an arbitrary subpopulation with n > 0 is essentially unknown. Finally, the physiology of the minority cells has not been characterized. It is unclear whether, in addition to low LamB expression, other aspects of biological functions are also different for these minority cells, namely, what are their relations with minority cells selected using different environmental stresses, such as starvation or antibiotics. In view of their important roles in environmental adaptation, in various diseases (19,35), and potentially in evolution, a fundamental understanding of minority cells remains a significant challenge.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for helpful conversations with R. Moldovan, S. Chattopadhyay, C. Yeung, R. Hendrix, and R. Duda. We also thank G. Fisher and Y. Creeger at the Molecular Biosensor and Imaging Center at Carnegie Mellon University as well as A. Donnenberg and E. M. Meyer at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Flow Cytometry Facility for help with flow cytometry.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. PHY-0646573. E.C. acknowledges partial support by the National Science Foundation during this project as a GK-12 Fellow under grant No. 0338135 (GK-12: The Pittsburgh Partnership for Energizing Science in Urban Schools).

Editor: Arup Chakraborty.

References

- 1.Moldovan, R. The interaction between λ-phage and its bacterial host. PhD Thesis. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

- 2.Schrag, S. J., and J. E. Mittler. 1996. Host-parasite coexistence: the role of spatial refuge in stabilizing bacteria-phage interactions. Am. Nat. 148:348–377. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chao, L., B. R. Levin, and F. M. Steward. 1977. A complex community in a simple habitat: an experimental study with bacteria and phage. Ecology. 58:369–378. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin, B. R., F. M. Stewart, and L. Chao. 1977. Resource-limited growth, competition and predation: a model and experimental studies with bacteria and bacteriophage. Am. Nat. 111:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodin, S. N., and V. A. Ratner. 1983. Some theoretical aspects of protein coevolution in the ecosystem “phage-bacteria,” I. The problem and II. The deterministic model of microevolution. J. Theor. Biol. 100:185–195, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenski, R. E., and B. R. Levin. 1985. Constraints on the coevolution of bacteria and virulent phage: a model, some experiments, and predictions for natural communities. Am. Nat. 125:585–602. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lenski, R. E. 1988. Dynamics of interactions between bacteria and virulent bacteriophage. In Advances in Microbial Ecology. Vol. 10. R. M. Atlas, J. G. Jones, and B. B. Jorgensen, editors. Plenum Press, New York. 1–44.

- 8.Hofnung, M., A. Jezierska, and C. Braun-Breton. 1976. lamB mutations in E. coli K12: growth of lambda host range mutants and effect of nonsense suppressors. Mol. Gen. Genet. 145:207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAdams, H. H., and A. Arkin. 1997. Stochastic mechanisms in gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:814–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arkin, A., J. Ross, and H. H. McAdams. 1998. Stochastic kinetic analysis of developmental pathway bifurcation in phage lambda-infected Escherichia coli cells. Genetics. 149:1633–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elowitz, M. B., A. J. Levine, E. D. Siggia, and P. S. Swain. 2002. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 297:1183–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai, L., N. Friedman, and X. S. Xie. 2006. Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature. 440:358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu, J., J. Xiao, X. Ren, K. Lao, and X. S. Xie. 2006. Probing gene expression in live cells, one protein molecule at a time. Science. 311:1600–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg, H. C., and E. M. Purcell. 1977. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 20:193–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moldovan, R., E. Chapman-McQuiston, and X. L. Wu. 2007. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys. J. 93:303–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golding, I., J. Paulsson, S. M. Zawilski, and E. C. Cox. 2005. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell. 123:1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Even, A., J. Paulsson, N. Maheshri, M. Carmi, E. O'Shea, Y. Pilpel, and N. Barkai. 2006. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat. Genet. 38:636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehring, K., A. Charbit, E. Brissaud, and M. Hofnung. 1987. Bacteriophage lambda receptor site on the Escherichia coli K-12 LamB protein. J. Bacteriol. 169:2103–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domingue, G. J., and H. B. Woody. 1997. Bacterial persistence and expression of disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:320–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaban, N. Q., J. Merrin, R. Chait, L. Kowalik, and S. Leibler. 2004. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 305:1622–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee, B., S. Balasubramanian, G. Ananthakrishna, T. V. Ramakrishnan, and G. V. Shivashankar. 2004. Tracking operator state fluctuations in gene expression in single cells. Biophys. J. 86:3052–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villaverde, A., A. Benito, E. Viaplana, and R. Cubarsi. 1993. Fine regulation of cI857-controlled gene expression in continuous culture of recombinant E. coli by temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3485–3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbs, K., D. D. Isaac, J. Xu, R. W. Hendrix, T. J. Silhavy, and J. A. Theriot. 2004. Complex spatial distribution and dynamics of an abundant Escherichia coli outer membrane protein, LamB. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1771–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. 2 ed. 1992, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- 25.Schwartz, M. 1976. The adsorption of coliphage lambda to its host: effect of variation in the surface density of receptor and in phage-receptor affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 103:521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novick, A., and M. Weiner. 1957. Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 43:553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szmelcman, S., and M. Hofnung. 1975. Maltose transport in Escherichia coli K-12: involvement of the bacteriophage lambda receptor. J. Bacteriol. 124:112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirmer, T., T. A. Keller, Y. F. Wang, and J. P. Rosenbusch. 1995. Structural basis for sugar translocation through maltoporin channel at 3.1 angstrom resolution. Science. 267:512–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ptashne, M. 1986. A Genetic Switch, Gene Control and Phage Lambda. Blackwell Scientific Publications and Cell Press, Palo Alto.

- 30.Chapman-McQuiston, E. L. The effect of noisy protein expression on E. coli/phage dynamics. PhD thesis. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh.

- 31.Luria, S. E., and M. Delbruck. 1943. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics. 28:491–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz, M. 1987. The maltose regulon. In Escherichia coli & Salmonella typhimurium, Cellular and Molecular Biology, F. C. Neidhardt, editor. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. 1482–1502.