Abstract

Fatty acids (FA) are important nutrients that the body uses to regulate the storage and use of energy resources. The predominant mechanism by which long-chain fatty acids enter cells is still debated widely as it is unclear whether long-chain fatty acids require protein transporters to catalyze their transmembrane movement. We use stopped-flow fluorescence (millisecond time resolution) with three fluorescent probes to monitor different aspects of FA binding to phospholipid vesicles. In addition to acrylodan-labeled fatty acid binding protein, a probe that detects unbound FA in equilibrium with the lipid bilayer, and cis-parinaric acid, which detects the insertion of the FA acyl chain into the membrane, we introduce fluorescein-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine as a new probe to measure the binding of FA anions to the outer membrane leaflet. We combined these three approaches with measurement of intravesicular pH to show very fast FA binding and translocation in the same experiment. We validated quantitative predictions of our flip-flop model by measuring the number of H+ delivered across the membrane by a single dose of FA with the probe 6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl) quinolinium. These studies provide a framework and basis for evaluation of the potential roles of proteins in binding and transport of FA in biological membranes.

INTRODUCTION

Long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) move in and out of cells continuously, but the movements of these small molecules are difficult to follow, both in model membranes and in cell membranes. One has to take into account their amphipathic properties of having an ionizable headgroup and hydrophobic tail, and their low solubility in water. These properties contrast markedly with those of glucose and make it more difficult to predict the mechanism of transport of LCFA through a membrane (1). Questions about whether the steps of membrane transport in cells can be described mechanistically as diffusion, or whether proteins facilitate LCFA transport across a lipid bilayer have persisted for decades. The proposals range from non-energy-dependent diffusion through the lipid bilayer to transport by putative transporters such as fatty acid transport protein (FATP), fatty acid translocase (FAT)/CD36, or caveolin-1 (2–16).

The controversies over LCFA transport in the plasma membrane of cells are fueled by disagreements about numerous issues, including: i), theoretical models of transport in protein-free phospholipid bilayers, such as whether the energy barrier for translocation of a LCFA across the bilayer is lower or higher than the barrier for its dissociation from the bilayer into the water phase (2,3); ii), methodologies for measuring LCFA transport, such as whether derivatized LCFA are reliable models for natural LCFA, or whether some methods of adding LCFA to membranes produce artifactual results (4–6); and iii), whether methods clearly distinguish membrane transport processes from intracellular metabolism of LCFA (7).

All models of transport of LCFA through membranes must take into account the fundamental properties of LCFA in phospholipid bilayers, which comprise the major portion of the surface area of biomembranes. The postulate of the requirement of a specific protein to catalyze the transmembrane movement of LCFA (as proposed for the FATP family and for CD36 (8–11)) is predicated on the hypothesis that the lipid bilayer is impermeable or poorly permeable to LCFA. A low permeability could be a result of a low affinity of LCFA for a membrane or slow kinetics of adsorption, translocation, and possibly dissociation (12).

To test such an assumption, we measured the transmembrane movement of LCFA by monitoring the pH inside protein-free phospholipid vesicles after addition of oleic acid (OA) to the external buffer (13). We argued that the rapid decrease in pH was a direct consequence of the rapid inward flux of LCFA in the un-ionized form. This supported our hypotheses that 50% of the LCFA in the outer leaflet of the membrane becomes ionized on binding and that the energy barrier for translocation of the uncharged LCFA is lower than that of the charged species (13). Although our results support the notion that model membranes are permeable to LCFA (12), our pH assay provides only an indirect measurement of adsorption of the LCFA to the outer membrane leaflet, and relies on the assumption that binding is as fast as or faster than flip-flop. Moreover, direct measurements of the kinetics of binding of LCFA to model membranes are lacking.

We use three fluorescent probes to monitor binding of OA to the outer leaflet of phospholipid vesicles by stopped-flow fluorescence to achieve a higher time resolution (milliseconds) than typical on-line fluorescence studies. One probe is attached to the headgroup of a phospholipid fluorescein-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine (FPE) intercalated into the outer membrane leaflet and measures the arrival of the charged carboxyl headgroup of LCFA at the aqueous polar interface of the bilayer. A second probe is an intrinsic fluorophore in a natural LCFA, cis-parinaric acid, which detects the insertion of the fatty acyl chain. A third probe (ADIFAB, an acrylodan-labeled fatty acid binding protein), when added to the external buffer, detects the depletion of LCFA from the buffer as they adsorb to the bilayer without providing information about how the LCFA binds. We combined each of the three approaches with measurement of intravesicular pH to monitor binding and translocation in the same experiment. We also used the probe SPQ, which provides an accurate quantitation of H+ in the intravesicular volume, to test our quantitative prediction of the flux of H+ associated with LCFA flip-flop (13,14).

Our new data support our previous hypothesis that membrane association and flip-flop are very fast processes in model membranes. Additionally, our derivations of permeability coefficients for OA are supported by our direct measurements showing that adsorption is faster than transmembrane movement or desorption of LCFA, as we had assumed in our calculations (12).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

2′,7′-Bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein) (BCECF) acid, fluorescein DHPE or N-(fluorescein-5-thiocarbamoyl)-1,2,dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, tri-ethylammonium salt (FPE), 6-methoxy-N-(3-sulfopropyl) quinolinium (SPQ), calcein, and cis-parinaric acid were purchased from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Pyranine (8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid, tri-sodium salt) was purchased from Eastman Kodak (Rochester, NY). ADIFAB1 was purchased from FFA Sciences (San Diego, CA). N-tris(hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethane sulfonic acid (TES), TEA (tetraethylammonium), calcein, Triton X-100, fatty acids (99% pure), nigericin, and BSA (essentially fatty acid-free) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Phosphatidylcholine (PC) isolated from chicken egg was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Sephadex G-25 was purchased from Amersham Biosciences/GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ).

Fluorescence instrumentation

On-line fluorescence measurements were made with a Spex Fluoromax-2 from Jobin Yvon (Edison, NJ) equipped with a temperature-controlled stirred cuvette. Stopped-flow experiments were done with a stopped-flow apparatus (Hi-Tech Scientific, Salisbury, UK) comprised of a pressure-driven pneumatic drive unit and two glass syringes with a 400 μl total sample mixing volume. Sample temperature was maintained by an external water bath (22°C) that delivered a continuous flow of water to warm a small metal plate located beneath the cuvette. The sample holder was also equipped with a magnetic stirrer to facilitate rapid sample mixing during on-line measurements.

LCFA addition to vesicles

The addition of LCFA in on-line fluorescence experiments in this study uses a protocol (12) in which an aliquot (2–5 μl) of a concentrated LCFA stock solution (10 mM K+-salt or dissolved at higher concentrations in DMSO) is added to a stirred cuvette containing vesicles (phospholipid concentration of 100 μM to 1 mM). Preparation of the K+-salt of LCFA has been described previously (12,15). Aliquots of LCFA were added to specific final concentrations in on-line experiments. With mixing, the LCFA are assumed to become diluted rapidly before binding to the lipid bilayer. In contrast, initial concentrations (2X) were used to prepare solutions of LCFA for stopped-flow studies. LCFA in the stopped-flow experiments became twofold diluted after mixing, thereby exposing vesicles to concentrations that were below the solubility limit of the LCFA used in these measurements.

Pyranine and BCECF to measure OA transmembrane movement (flip-flop)

Small unilamellar vesicles (SUV) were prepared from PC by sonication in Hepes/KOH buffer (pH 7.4) as before (13). Large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) were made of PC by extrusion in Hepes/KOH buffer (pH 7.4) as described previously (16). In experiments using a pH probe (0.2–1 mM BCECF acid or 0.1 mM pyranine) trapped inside the vesicles, untrapped probe was removed by gel filtration in a 50 ml column (Sephadex G-25). This procedure removes all of the untrapped pH fluorophore (13–15). As shown by addition of pH fluorophore to vesicles prepared in this manner, traces of probe in the external buffer, if present, would not interfere with the measurement of pH in the small volume inside vesicles due to the strongly-buffered, large extravesicular volume (data not shown). The exact PC concentration in the eluted vesicle suspension was determined from an aliquot of the sample used for fluorescence measurements by using the Bartlett method to assay total phosphorus (17).

BCECF fluorescence was measured as a ratio of two excitation wavelengths (R = 505 nm/439 nm) using a bandpass of 3 nm (BCECF emits at 535 nm). Pyranine was excited at 455 nm, and emission was measured at 509 nm using a bandpass of 3 nm. On-line fluorescence experiments were carried out by adding vesicles to 2.5–3.0 ml of Hepes/KOH buffer (∼500 μM final [PC]) and by measuring pyranine or BCECF fluorescence with time. LCFA was delivered into the suspension through the injection port above the cuvette with continuous stirring by a mini stir bar. When monitoring the fluorescence of a single probe, changes in fluorescence (ΔF) can be resolved to within 2 s. When two probes are combined for dual fluorescence measurements, the instrumentation switches between frequencies, and the time resolution is >2 s depending on which probes are being used (2–3 s for the probes used in these studies).

Our stopped-flow measurements begin after a 10 ms delay for mixing (dead time) and data are sampled with a time resolution of 1 ms. The relationship between fluorescence and pHin was calibrated by measuring fluorescence emission after permeabilizing the vesicles with 1 μg nigericin and varying external pH through addition of small aliquots of H2SO4 and KOH as described elsewhere (13).

SPQ to quantitate H+ flux across the membrane

We measured the molar amount of transmembrane H+ flux across the bilayer (∂nH+) using a method published previously for the probe SPQ (14). SPQ (2 mM) was trapped in the internal volume of LUV with buffer (pH 7.4) consisting of 25 mM TES (TEA-salt) and 50 mM K2SO4. External SPQ was removed by gel filtration as described above for pH probes. SPQ fluorescence was measured by exciting at 347 nm and measuring fluorescence emission at 442 nm with a bandpass of 8 nm. OA was delivered to rapidly stirred cuvettes as described above.

The intravesicular volume of LUV was measured by comparing the fluorescence of a 5-μl aliquot of vesicles before and after the gel filtration step and correcting for dilution after elution from the column. With knowledge of the internal volume (1.85 μl/mg PC), addition of H2SO4 to permeabilized vesicles (nigericin) permitted the calibration of ∂nH+ with changes in SPQ fluorescence, which result from changes in the TES anion concentration (TES anions quench SPQ fluorescence) (14). On-line fluorescence experiments (22°C) were carried out by adding vesicles containing SPQ to 2.5–3.0 mL of TES-TEA/K2SO4 buffer (∼500 μM final [PC]).

ADIFAB, cis-parinaric acid and FPE to measure OA adsorption

OA binding to vesicles was monitored by both on-line and stopped-flow fluorescence using three different fluorophores: ADIFAB, cis-parinaric acid, and FPE. For dual fluorescence on-line measurements, the fluorescence of the binding probe and the entrapped pH probe were measured continuously with time. OA was delivered to the external buffer of suspensions of vesicles in rapidly stirred cuvettes as described above. The fluorescence of both probes was sampled in rapid sequence with a time resolution of 2–3 s (i.e., the time required for the emission monochromator to switch between emission wavelengths of the particular probes used).

ADIFAB (0.2 μM) was added to the external buffer of a suspension of SUV with entrapped pyranine. SUV were prepared in “Measuring Buffer” at pH 7.4 (20 mM Hepes/KOH, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2HPO4) (18,19). ADIFAB is excited at 386 nm and fluorescence was measured as a ratio of two emission wavelengths (R = 505 nm/432 nm), using a bandpass of 5 nm. ADIFAB measures the unbound LCFA ([OA]u) remaining in solution after OA partitions into the membrane (1). The unbound concentration of OA in suspension with ADIFAB is calculated as follows in Eq. 1:

|

(1) |

where Kd is the equilibrium binding constant for a specific OA to ADIFAB, Q is the ratio of fluorescence emission (at 432 nm) in the absence and in the presence of saturating concentrations of OA (18). R0 and Rmax correspond to the ADIFAB emission ratios in the presence of zero and saturating concentrations of OA, respectively.

The partitioning of OA into model membrane vesicles is calculated from Eq. 2 after the ADIFAB fluorescence reaches equilibrium:

|

(2) |

where [OA]t is the total amount of added OA, [OA]m is the concentration of OA in a membrane with volume (Vm) and [OA]u is the concentration of unbound OA in a vesicle suspension with a total volume (Vw). Vm/Vw has been reported previously to be 10−3 /mmol/l phospholipid (1).

The arrival of the anionic LCFA carboxyl group at the membrane-water interface was detected by FPE bound to the outer leaflet of SUV with entrapped pyranine. FPE was excited at 490 nm, and emission was measured at 520 nm with a bandpass of 3 nm. A stock solution of FPE was prepared as described previously (20). Briefly, FPE dissolved in a 5:1 (v/v) mixture of chloroform:methanol was dried under N2 gas, lyophilized for 1 h and re-dissolved in an equivalent volume of 100% DMSO. FPE (0.2 mol % relative to PC) was then added to the eluted SUV suspension (after sonication and gel filtration) and incubated in the dark for 1 h at 22°C to allow the fluorescent-labeled phospholipid to adsorb into the outer leaflet of the vesicles.

Insertion of the LCFA acyl chain into the membrane was measured by adding cis-parinaric acid (PA) dissolved in Hepes buffer to a suspension of SUV with entrapped pyranine. The fluorescence of PA was measured by exciting at 324 nm and measuring emission at 416 nm with a bandpass of 3 nm.

Stopped-flow fluorescence measurements of LCFA adsorption and transmembrane movement (flip-flop)

For dual fluorescence stopped-flow experiments, equal volumes of a suspension of SUV containing pyranine were placed in one syringe and 6, 12, and 18 μM PA or 3 and 6 μM OA (dissolved in the same Hepes/KOH buffer) were placed in the other syringe of the stopped-flow apparatus. The final PC concentration after mixing was ∼700 μM PC. Because it is not possible for the instrument to switch between wavelengths in the fast time resolution (1 ms) of stopped-flow experiments, the fluorescence of each probe was monitored separately on rapid mixing of the LCFA and vesicle solutions (dead time = 10 ms). Each experiment was carried out for a one probe and then repeated for the second probe. A bandpass of 3 nm was used for all stopped-flow measurements except in the case of measuring PA fluorescence, which required a 5 nm bandpass.

Vesicle permeabilization assay

PC (8 mg) was hydrated in a buffer (pH 7.4) containing 70 mM calcein, 50 mM KCl, and 20 mM sodium phosphate and was sonicated subsequently to clarity as described above. External calcein was removed by a Sephadex 75 column, eluting with 100 mM KCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4). For the fluorescence measurement, OA was added to a stirred cuvette with 2.5 mL of the same buffer containing SUV with entrapped calcein (100 μM final PC concentration), and calcein fluorescence was measured with time at 22°C. The probe was excited at 490 nm and emission was measured at 520 nm. Maximum permeabilization was measured by adding 2.5 μl of 20% Triton X-100.

RESULTS

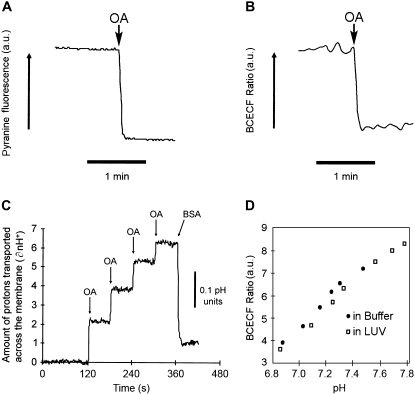

Measurement of pHin by different probes and quantitation of H+ flux associated with OA diffusion

The measurement of pHin in LUV by three different fluorescent probes (pyranine, BCECF, and SPQ) after the addition of the same amount (10 nmol) of OA is shown in Fig. 1 A, B, and C. In previous studies of phospholipid vesicles, we chose to use pyranine because: i), it is water-soluble and does not interact with phospholipids or LCFA; ii), its fluorescence is linearly related to changes in pH in the range 6.8–8.2; and iii), it has a high quantum yield. However, pyranine cannot be introduced into live cells, whereas BCECF is a suitable pH fluorophore for such applications (7,21,22). BCECF (Fig. 1 B) shows a rapid decrease in fluorescence (t1/2 < 2 s) that is similar to pyranine (Fig. 1 A) but with significantly lower signal/noise as a result of its lower quantum yield. Similar to pyranine, the fluorescence ratio of BCECF is linear in the pH range of 6.4–7.6 and its reliability to detect pH changes is not altered by its entrapment within lipid vesicles (Fig. 1 D).

FIGURE 1.

Measuring the flip-flop of fatty acids to the inner membrane leaflet using pH-sensitive fluorophores. LUV were prepared containing entrapped pyranine (A), BCECF acid (B), and SPQ (C). Vesicles were suspended in buffer (pH 7.4) to a final PC concentration of 500 μM. Single or multiple doses of oleic acid (10 nmol) caused the fluorescence of each probe to change rapidly with a t1/2 < 2 s, indicating rapid diffusion of OA to the inner leaflet. The final concentration of OA after each addition was below the solubility limit (3.3 μM per dose). In C, SPQ fluorescence showed the instantaneous influx of 2.5 nmol H+ per 10.0 nmol of added OA. The subsequent addition of BSA (2.8 mol BSA per 1 mol OA) resulted in extraction of OA from the LUV and an instantaneous efflux of H+ (t1/2 < 2 s). (D) Shows that the fluorescence titration of trapped and untrapped BCECF is not significantly different.

Neither pyranine nor BCECF permits rigorous quantitation of the H+ flux across the membrane that is associated with LCFA flip-flop. For this purpose, we used the probe SPQ to test the predictions made by the LCFA flip-flop model (13). OA added to a suspension of LUV with entrapped SPQ causes an immediate increase in fluorescence on delivery of H+ into the intravesicular volume, as predicted (1,13,15,16), but with lower sensitivity than with both pyranine and BCECF (Fig. 1 C). Sequential additions of OA (3.3 μM; 10 nmol) were used to generate data to calculate the influx of H+ (as described in Materials and Methods). The y axis of Fig. 1 C shows the calculated nmol of H+ (∂nH+) delivered to the intravesicular volume.

The first addition of 10 nmol of OA to the external buffer resulted in an instantaneous influx (t1/2 < 2 s) of ∼2.5 nmol of H+, exactly as predicted by our model of LCFA flip-flop (i.e., 1 H+ for every 4 LCFA molecules added to the outer leaflet) (13). Subsequent additions of 10 nmol of OA resulted in progressively smaller influxes of H+. This result was also predicted by our model of interfacial ionization and flip-flop: as pHin decreases, the ionization of LCFA at the inner leaflet is suppressed and the delivery of H+ (and their subsequent detection by SPQ) is reduced. Addition of albumin to the external buffer (1 mol of BSA per 2.8 mol of added OA; 40 total nmol of OA) results in an instantaneous and equally rapid efflux of H+ (t1/2 < 2 s). The reversal of the OA-induced decreases in pHin by BSA reflects the outward movement of OA, which would require the flip-flop of un-ionized OA to the outer leaflet and, thus, a reverse flux of H+ (13). The results with SPQ validate this interpretation of the effect of albumin on pHin.

Simultaneous measurements of adsorption and flip-flop of LCFA

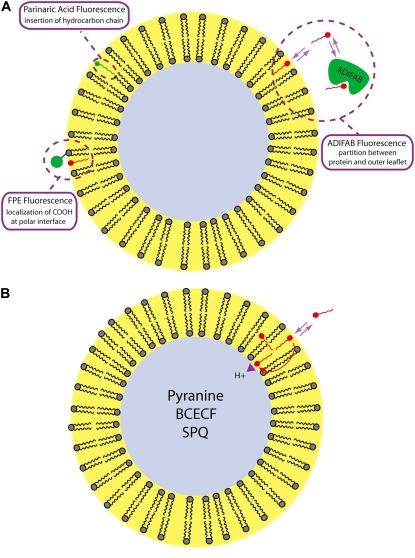

The major goal of this study was to provide novel information about the kinetics of LCFA binding (adsorption) to protein-free phospholipid bilayers on a fast timescale. We used three fluorescence probes that each report on a different physical aspect of binding, including a novel fluorophore for detecting LCFA binding to outer membrane leaflet, FPE (Fig. 2). The second goal was to compare the kinetics of LCFA adsorption with the kinetics of the pH changes inside the vesicle that we have attributed to flip-flop. Fortuitously, for each of the chosen probes, the excitation and emission frequencies are well separated, and it was feasible to measure the adsorption of LCFA and the intravesicular pH simultaneously in the same vesicle sample by on-line fluorescence. The faster timescale (milliseconds) of the stopped-flow studies does not permit switching of wavelengths to both probes in the same sample. Therefore, measurements were made for one probe and then repeated for the second probe under otherwise identical conditions.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic diagram of the fluorescence probes and assays used to discriminate FA binding and flip-flop in membranes. (A). ADIFAB, FPE, and cis-parinaric acid are used to monitor LCFA binding to the outer leaflet. ADIFAB measures the concentration of unbound LCFA in equilibrium with the membrane and cis-parinaric acid, the insertion of the acyl chain into the hydrophobic bilayer. FPE detects the arrival of the charged LCFA carboxyl at the membrane surface. These charged FA molecules shift the pKa of FPE in the membrane and induce a decrease in its fluorescence emission intensity. Most LCFA are ionized in solution but become 50% un-ionized on binding to membranes due a shift in their pKa to ∼7.5. (B). Un-ionized LCFA rapidly diffuse to the inner leaflet, reach ionization equilibrium, and release H+ to the internal volume that can be detected by entrapped pH-sensitive fluorophores such as pyranine, BCECF, and SPQ. It is important to note that entrapped probes measure the combined steps of binding and flip-flop. In addition to sensing pH changes, SPQ can also be used to quantitate H+ flux across the membrane in response to the addition of LCFA to the external buffer. Adapted from (43).

The pH changes shown in Fig. 1 reflect the presence of un-ionized OA in the phospholipid bilayer that have diffused across the bilayer and released a proton but do not provide direct evidence for the presence of the OA anion. To test our hypothesis that the LCFA anion is also present (because LCFA have a pKa of ∼7.5 at the water-membrane interface) (1,13,24), we used the membrane surface potential probe FPE, a fluorescein-labeled phospholipid molecule with a pKa of ∼7.3. Its fluorescence changes with the protonation state of the fluorescein moiety and in a well-buffered solution, as in our assays, is sensitive to charged molecules that alter the surface potential of the membrane (20,25–28) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, FPE is a probe specifically for the outer leaflet of the bilayer when added to preformed vesicles because the charged headgroup prevents flip-flop to the inner leaflet.

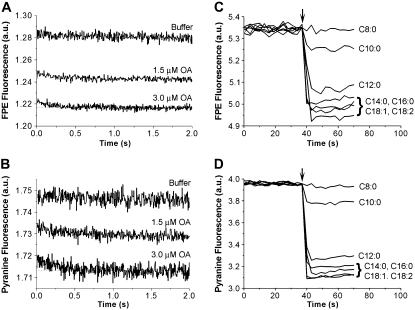

Stopped-flow fluorescence measurements were carried out to measure the response of FPE-labeled vesicles (SUV) to the addition of OA. Fig. 3 A shows that the FPE fluorescence decreased and was >90% complete within the mixing dead time (10 ms). In parallel experiments with the same concentration of OA, very fast decreases in pyranine fluorescence were observed (Fig. 3 B). The t1/2 for this data and subsequent data from stopped-flow experiments was not calculated because the drop from the initial value (represented by: the control experiment − mixing vesicles with only buffer) is almost complete before the first time point is measured.

FIGURE 3.

Partitioning of different chain length fatty acids into SUV using the surface potential probe FPE. For the stopped flow measurements (A and B), a suspension of SUV (containing 0.1 mM pyranine) in 20 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.4 was mixed rapidly with increasing amounts of OA (1.5 and 3.0 μM final concentration) in the same buffer. To minimize potential complications from the precipitation of OA, the initial concentration of OA (before mixing) was below the its estimated solubility limit of 5–6 μM at pH 7.4 (19). Vesicles were mixed with only buffer as a mixing control. The final PC concentration after mixing was 700 μM. Separate measurements were carried out while monitoring the fluorescence of FPE (A) and pyranine (B). All fluorescence traces are the average of 4–6 measurements. On-line FPE experiments were carried out by delivering a single dose of fatty acid (20 μM; arrow) to SUV (500 μM) labeled with 0.2 mol % FPE (containing 0.1 mM pyranine) in 50 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.4. The fatty acids used were octanoate (C8:0), decanoate (C10:0), laurate (C12:0), myristate (C14:0), palmitate (C16:0), oleate (C18:1), and linoleate (C18:2). FPE (C) and pyranine (D) were monitored simultaneously and the fluorescence of each probe changed rapidly with t1/2 < 2 s. The magnitude of the fluorescence change reflects increased partitioning of LCFA into the membrane.

In on-line fluorescence experiments, the binding and transmembrane movement of LCFA can be monitored simultaneously using identical experimental conditions (Materials and Methods). Fig. 3 C and D show that addition of LCFA with chain lengths of 8–18 carbons to a vesicle suspension resulted in a rapid decrease in FPE fluorescence (t1/2 < 2 s in this on-line measurement). Additionally, the magnitude of the FPE response was smaller for fatty acids with 8–12 carbon acyl chains (octanoate, C8:0; decanoate, C10:0; laurate, C12:0), whereas FPE responded similarly to all LCFA with 14–18 carbons (myristate, C14:0; palmitate, C16:0; oleate, C18:1; linoleate, C18:2). The simultaneous measurement of pyranine fluorescence showed changes that correlated closely with the FPE responses. The differences in the magnitude of fluorescence changes for medium and LCFA can therefore be explained by the physical–chemical properties of the different fatty acids, specifically the decreasing partition coefficient (Kp ) with decreasing acyl chain length and the very high affinity for LCFA with more than 12 carbons (12).

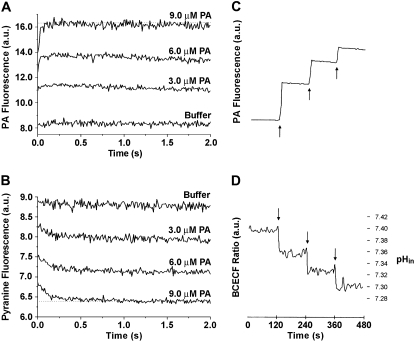

Although the common dietary LCFA lack fluorescent properties, cis-parinaric acid (PA) contains multiple conjugated double bonds that give rise to intrinsic fluorescence. As a second approach to monitor adsorption of LCFA to the phospholipid interface, we used PA to monitor directly the insertion of the acyl chain into the bilayer core. Because the membrane environment monitored by PA is the same in both membrane leaflets, the fluorescence changes of this probe will not report directly on the transmembrane movement of the LCFA. Therefore, the dual fluorescence approach with entrapped pyranine was used to monitor both events in the same vesicles. Fig. 4 A shows that the fluorescence of PA increased rapidly on mixing with SUV and is nearly complete within the 10 ms mixing dead time. Fig. 4 B shows that the flip-flop of PA to the inner leaflet was also extremely fast, though slightly slower than the adsorption.

FIGURE 4.

Dual fluorescence measurement of fatty acid binding and flip-flop using a pH-sensitive fluorophore and cis-parinaric acid. For the stopped flow measurements (A and B), a suspension of SUV (containing 0.1 mM pyranine) in 20 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.4 was rapidly mixed with increasing amounts of PA (3, 6, 9 μM final concentration) in the same buffer. Vesicles were mixed with only buffer as a mixing control. The final PC concentration after mixing was 700 μM. Separate measurements were carried out while monitoring the fluorescence of PA (A) and pyranine (B). All fluorescence traces are the average of 4–6 measurements. Parallel on-line experiments were carried out by delivering sequentially three equal doses of PA (20 μM PA; arrows) to a cuvette containing a suspension of SUV (500 μM) containing entrapped 0.2 mM BCECF in 100 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.4. PA (C) and BCECF (D) were monitored simultaneously and the fluorescence of each probe changed rapidly with t1/2 < 3 s. The calibration of BCECF fluorescence with pHin is described in the Materials and Methods.

In on-line fluorescence experiments we studied the sequential addition of PA to higher concentrations than that used in the stopped-flow experiments. In contrast to stopped-flow, on-line experiments use small aliquots of LCFA added to a large volume of vesicles in suspension, and sequential aliquots of LCFA can be added to the same vesicle sample. In Fig. 4 C, sequential additions of 50 nmol of PA (20 μM) to a suspension of SUV resulted in a rapid increase in PA fluorescence (t1/2 < 3 s). The fluorescence response of PA increased in a dose-dependent manner until the fluorescence changes appear to ‘saturate’ as the cumulative amount of added PA increases. This is the result of the self-quenching of PA in membranes that has been reported elsewhere (21). Fig. 4 D shows that the intravesicular pH changes rapidly and simultaneously with PA fluorescence (t1/2 < 2 s).

A third way of monitoring LCFA adsorption is to use the engineered acrylodan-labeled fatty acid binding protein, ADIFAB, which measures the depletion of LCFA from the buffer as they adsorb to the lipid bilayer. An advantage of ADIFAB is that the partition coefficient of LCFA into membranes can be calculated readily. In our experimental protocol, ADIFAB was added to the external buffer of a suspension of SUV after entrapment of pyranine and before addition of OA. The measurement of pHin and external unbound OA by stopped-flow is illustrated in Fig. 5 A and B. With each addition of OA, the ADIFAB fluorescence increased within a few milliseconds to a maximal value that reflects the concentration of unbound OA ([OA]u) in equilibrium with the vesicles. The maximal fluorescence, but not the kinetics, of ADIFAB was dose-dependent. Whereas the ADIFAB fluorescence does not provide any direct information about the precise localization of OA in the bilayer, the pyranine fluorescence reporting intravesicular pH detects the arrival of the OA carboxyl headgroup at the inner leaflet (13). Fig. 5 B shows that the pH decreased rapidly to an equilibrium value, as shown previously for OA (16). As a control experiment vesicles were mixed with buffer alone, and no fluorescence changes were observed (Fig. 5 A, bottom and B, top).

FIGURE 5.

Dual fluorescence measurement of fatty acid binding and flip-flop using a pyranine and ADIFAB. For the stopped flow measurements (A and B), a suspension of ADIFAB and SUV (containing pyranine) in 20 mM Hepes buffer at pH 7.4 was rapidly mixed with increasing amounts of OA in the same buffer (1.5 and 3.0 μM final concentration). Vesicles were mixed with only buffer as a mixing control. The final PC concentration after mixing was 700 μM. Separate measurements were carried out while monitoring the fluorescence of ADIFAB (A) and pyranine (B). All fluorescence traces are the average of 4–6 measurements. Parallel on-line experiments were carried out by delivering five equal doses of OA (10 nmol OA; arrows) sequentially to a cuvette containing a suspension of ADIFAB (0.2 μM) and SUV containing BCECF (500 μM) in “Measuring Buffer” at pH 7.4 (20 mM Hepes/KOH, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM Na2HPO4). ADIFAB (C) and BCECF (D) were monitored simultaneously and the fluorescence of each probe changed rapidly with t1/2 < 3 s. The concentration of unbound OA per total amount of added OA was plotted (E). A linear fit of these data yield the partitioning coefficient (Kp) of OA into PC membranes. The calibration of ADIFAB and BCECF fluorescence with unbound OA and pHin, respectively, is described in the Materials and Methods.

Fig. 5 C and D show an on-line fluorescence experiment in which each addition of OA (10 nmol) corresponded to a final concentration of 3.3 μM. As expected from the stopped-flow results, the changes in both ADIFAB fluorescence and BCECF fluorescence occur rapidly and simultaneously (t1/2 < 3 s). Thus, as expected, binding and flip-flop seem to be simultaneous events on this slower timescale (1,13,15).

The ADIFAB data provide information about thermodynamics as well as kinetics. Most importantly, the partition coefficient can be derived to assess the affinity of the LCFA for the vesicle bilayer. Fig. 5 E shows a plot of [OA]u (calculated as described in the Materials and Methods) versus the total amount of OA added to the vesicle suspension ([OA]t). The linear fit of these data yield a single equilibrium constant corresponding to the partitioning coefficient (Kp) of OA. The partition coefficient obtained from our data (Kp = 0.6 × 106) is in good agreement with previous determinations of Kp for OA (7,19,29). It should be noted that in our experiments, the initial baseline fluorescence of ADIFAB in the absence of any LCFA is typically between 0.2–0.3 a.u.; therefore our plot did not extrapolate to zero.

Vesicle permeability to calcein

The preceding results show no indication of membrane disruption when using our typical methods of LCFA addition to vesicles. To further assure that our methods of LCFA addition do not disrupt the vesicles, we carried out a permeabilization assay by trapping 70 mM calcein inside SUV. At this concentration, calcein fluorescence is completely quenched. However, if a small amount of calcein leaks out of the vesicle, the dilution of calcein entering the external buffer will result in a strong fluorescence increase. Addition of OA or palmitate at an even higher concentration than that used in this study (10 mol % LCFA relative to PC) did not cause any disruption of the vesicles (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of LCFA transport across membranes, i.e., transport of the unbound LCFA dissolved in the two aqueous phases on each side, involves a minimum of three steps that can be characterized thermodynamically and kinetically (13,30). Quantitative characterization of each step in a simple model membrane (a protein-free phospholipid bilayer) provides the foundation for evaluating the contribution of the lipid phase of membranes to LCFA transport. If any of these steps is slow, proteins might be required to facilitate diffusion.

We present results from three fluorescence assays for measuring adsorption of LCFA to a vesicle bilayer, each of which monitors a different physical aspect of adsorption (Fig. 2). With the soluble fluorescent-labeled LCFA binding protein (ADIFAB) placed in the external medium, thermodynamic (partition between membrane-bound LCFA and unbound LCFA) and kinetic data are obtained. This method does not give direct information about the precise mechanism of binding. The naturally fluorescent LCFA, cis-parinaric acid (PA), provides kinetic data reflecting insertion of the LCFA tail into the phospholipid bilayer. Finally, the fluorescent-labeled phospholipid (FPE) senses the insertion of the anionic group of the LCFA molecule into the water–lipid interface. A key assumption of our model of LCFA flip-flop is that in the membrane interface LCFA is present in both un-ionized and ionized forms; the FPE results provide a direct validation of the presence of ionized LCFA. Subsequently, information about translocation of the LCFA across the lipid bilayer was addressed with pH measurements of the internal volume in vesicles.

An important advantage of these fluorescence methods is that real-time measurements can be made without separation procedures. The three probes also can be used in combination with our original assay that measures intravesicular pH with a fluorescent pH probe, pyranine or BCECF (Fig. 1). When LCFA is added in the external buffer, these pH probes measure the combined steps of adsorption and translocation.

Validation of the LCFA diffusion model from measurements of adsorption and transmembrane movement

All fluorescence measurements showed very rapid binding of LCFA to the lipid membrane of phospholipids vesicles, with larger changes in fluorescence occurring as the concentration of the added LCFA was increased. Because of their hydrophobic nature, it is generally assumed (but not directly measured) that adsorption of LCFA to vesicles is extremely fast, limited only by the mixing conditions. In this study, all samples were mixed rapidly, using either a pressure-driven stopped-flow apparatus or a rapidly spinning mini stir bar. In the case of LCFA, the adsorption step might also be limited by the dissolution of aggregates of LCFA that form above the solubility limit in the particular experimental conditions. In the studies shown, OA was added at concentrations below its estimated solubility limit at pH 7.4. To minimize potential artifacts from osmotic changes (6), we typically used Hepes buffer (without added salts) to prepare both the vesicles and OA stock solutions used for stopped-flow measurements. Therefore, we conclude that the fluorescence changes for all three measurements show reliably that adsorption is >90% complete within at least a few milliseconds.

The PA results show that the acyl chain inserts into the hydrocarbon core of the bilayer, where its fluorescence is much higher compared to the aqueous phase. The results with FPE show that headgroup inserts into the bilayer equally rapidly. The ADIFAB data also show rapid binding. The calculated partition coefficient (Kp) for OA derived from the concentration-dependent changes in ADIFAB (0.6 × 106) is typical for the affinity of the poorly water-soluble LCFA for phospholipid bilayers. Interestingly, the Kp is very similar to that calculated from similar experiments with intact adipocytes and plasma membrane vesicles (isolated from adipocytes), which we interpreted as evidence for OA binding primarily to the membrane lipids (7).

The stopped-flow fluorescence traces for adsorption of LCFA to vesicles did not show a slow component that might be indicative of slow translocation across the bilayer. The PA experiment is not expected to give any information about the transmembrane movement, as the microscopic environment at the end of the acyl chain (where the fluorescent region is located) would be the same on each leaflet. FPE could in principle give indirect information about the transmembrane movement. For example, if LCFA flip-flop were slow after their fast adsorption, the amount of LCFA (anions) in the outer leaflet in proximity to the probe would decrease enough to yield a fluorescence increase.

However, assumptions about the sensitivity of these probes to translocation of LCFA are not necessary. Measurements of flip-flop were made in parallel experiments using stopped-flow and in simultaneous experiments with on-line fluorescence using the established pH assay. On a timescale of milliseconds, all three measurements of adsorption showed kinetics that were as fast as or faster than the pH changes. This validates our attribution of the pH changes inside vesicles to the adsorption of LCFA to the outer leaflet followed by translocation of un-ionized LCFA to the inner leaflet as proposed in (13). Had the translocation step occurred on a significantly slower timescale than the adsorption step, either our hypothesis or our experimental procedure could be questioned. Although the possibility of bilayer disruption using some of our protocols with LCFA has been raised by one research group (4), this and previous studies from our group and others (6,31) show no evidence for any unexpected or artifactual perturbation of the phospholipid bilayer with the addition of low μM concentrations of OA.

Validation of the LCFA diffusion model using FPE to detect ionized LCFA

We proposed previously that the kinetics of transbilayer movement of LCFA in phospholipid bilayers can be measured by a pH dye trapped inside model membranes (phospholipid vesicles). In simple PC vesicles, the apparent pKa measured by NMR of OA and other saturated fatty acids ranging from 8–26 carbons is ∼7.5 (24). Under our initial experimental conditions, pHin = pHout = 7.4, the LCFA will be ∼50% ionized when present at the phospholipid-water interface. Indeed, our pH assay provided evidence for the ionization of LCFA on the inner leaflet after flip-flop of the un-ionized LCFA. FPE allowed us to show directly the presence of the LCFA anion in the outer leaflet by observing the predicted change (decrease) in fluorescence intensity when LCFA was added to vesicles labeled with FPE. We further showed the sensitivity of this probe to the partitioning of LCFA from the aqueous phase into the phospholipids bilayer by the greater changes in fluorescence caused by longer-chain fatty acids. The correspondence between LCFA adsorption to the phospholipid vesicles and flip-flop was shown by the simultaneous measurements of FPE and pyranine fluorescence as a function of fatty acid chain length.

Validation of the LCFA diffusion model by quantitating H+ flux using SPQ

The hypothesis of flip-flop (13), as discussed briefly above, has a quantitative correlate that equilibration of LCFA across the bilayer by diffusion will result in the donation of ∼1 H+ to the intravesicular volume for every four molecules of LCFA that bind to the external leaflet (13). Our previous studies compared the predicted decrease in pH with the observed pH decrease (13,15,16). The theoretical pH change was based on the flip-flop model, the buffering strength, and the calculated volume of the vesicle. We found excellent agreement between the theoretical and the measured pH change, but this approach was limited because it does not directly quantitate the number of protons transported.

In this study, SPQ was used to measure directly the flux of H+ across the membrane. The addition of 10 nmol of OA resulted in an instantaneous influx of ∼2.5 nmol of H+, exactly the number of protons predicted by our model of LCFA flip-flop. Furthermore, the addition of BSA removed nearly all of the delivered H+ from the inner volume, and pHin was restored to its initial value, validating our earlier hypothesis that the restoration of pHin in vesicles after the addition of BSA reflects the reverse “flop” of un-ionized LCFA to the outer membrane leaflet (13). Lastly, changes in SPQ fluorescence also occurred with a t1/2 < 2 s, as observed with other probes such as pyranine and BCECF.

Another research group has reported much lower fluxes of H+ after addition of LCFA to vesicles, which seems to contradict the quantitative predictions of our model. For example, 100 nmol of palmitate added to a suspension of LUV resulted in release of only 3.3 nmol H+ in one study (32). However, the high concentration (50 μM) of palmitate likely resulted in precipitation of most of the added LCFA, and only a small portion might have adsorbed to the bilayer. To avoid such possible complications in our experiments, each addition of OA yielded final concentrations up to 3.0 μM, which is below the estimated solubility limit of OA (∼5–6 μM) (19) and amounts to 0.6 mol % LCFA relative to PC in our protocol.

Our assay of adding unbound OA also avoids the complication of using a donor such as albumin, which adds an extra kinetic step of dissociation of the LCFA from the donor. Published values for the half-time of LCFA dissociation from albumin span a wide range, from hundreds of milliseconds (33) to seconds (31,34), all of which are much slower than adsorption, as we show in this study. Thus, using albumin as a delivery vehicle would preclude the accurate measurement of the kinetics of the adsorption or translocation steps of LCFA transport in membranes. At the same time, the use of unbound OA as the only method to deliver LCFA will not resolve the question of whether the mechanism of transport of LCFA in cell membranes is fundamentally different when cells are exposed to lower concentrations in equilibrium with albumin or other donor vehicles (35). The adsorption kinetics measured in this study are essential for evaluation of kinetics with various types of donors in studies of both model membranes and cells.

Relevance to biological systems

The main focus of our research on LCFA transport into cells has been to decipher mechanistic details by use of fluorescence approaches. In this study, we evaluated the pH probes BCECF and SPQ for the detection of flip-flop in vesicles. Pyranine has the greatest sensitivity but cannot be incorporated into the cytosol of living cells. Although SPQ was important for validation of our model of flip-flop, it also cannot be incorporated into cells. On the other hand, BCECF can be incorporated into the cytoplasm of living cells by using the methyl ester derivative, BCECF-AM, which is then hydrolyzed to the fluorescent free acid. BCECF should provide an accurate and reliable measure of intracellular pH, as illustrated in Fig. 1. To date, changes in intracellular pH as monitored by BCECF have been reported for adipocytes (7), pancreatic β cells (36), cardiomyocytes (37), Jurkat T-cells (38), HEK293 cells (22), and HepG2 cells (21) in response to addition of LCFA to the external buffer.

The use of fluorescence probes to measure adsorption of LCFA to cells has had rather limited applications to date (ADIFAB and BCECF in adipocytes (7,39) and HEK cells (22), and PA and BCECF in adipocytes (40) and HepG2 cells (21)). The detailed investigations with simple model membranes herein provide a basis for their use in the more complex membranes in biological systems, and show that the fluorescent probes can be used under experimental conditions without artifacts, except for the self-quenching of PA as it accumulates in the lipid membranes (Fig. 4 and (21)). However, the very fast kinetics of adsorption, if they occur in cells, cannot be measured by stopped flow because of rapid mixing and instrumental limitations, but there may be other impediments to the access of LCFA to the phospholipid bilayer that appreciably slow the adsorption of LCFA. The probes described would then provide an opportunity to monitor slower steps of LCFA transport into cells, as well as depletion of the plasma membrane supply of LCFA during intracellular metabolism. In our most recent studies of cells overexpressing caveolin-1 using ADIFAB in the external buffer and BCECF in the cytoplasm, we found fast adsorption and translocation of LCFA (seconds) that was followed by a slower step (min) that was dependent on the overexpression of caveolin-1. The results suggested that caveolin-1 did not affect adsorption of LCFA to the extracellular leaflet of the plasma membrane or the fast translocation after adsorption, but did affect intracellular “trafficking,” consistent with the observation that caveolin-1 can localize to the cytosolic leaflet of the plasma membrane (22). Further studies are in progress with extracellular and intracellular probes to delineate i), whether proteins can enhance adsorption of LCFA to membranes; ii), whether this occurs with or without enhanced movement of the LCFA across the membrane by FAT/CD36; and iii), what step of membrane transport is affected by “inhibitors” of LCFA transport (41,42).

In summary, our experimental protocols provide simple and direct measurements of LCFA adsorption to membranes. They do not depend on theoretical models, deconvolution of multi-exponential fluorescence traces, or assumptions about the delivery of LCFA from donors. Our results show fast adsorption to protein-free bilayers, and validate our hypothesis-based measurements of pH inside vesicles for monitoring the kinetics of flip-flop. They provide a framework and basis for evaluation the potential roles of proteins in binding and transport of LCFA in biological membranes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kellen Fontanini for designing and producing Fig. 2 of this publication.

Editor: Richard E. Waugh.

References

- 1.Hamilton, J. A., and F. Kamp. 1999. How are free fatty acids transported in membranes? Is it by proteins or by free diffusion through the lipids? Diabetes. 48:2255–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinfeld, A. M. 2000. Lipid phase fatty acid flip-flop, is it fast enough for cellular transport? J. Membr. Biol. 175:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pownall, H. J., and J. A. Hamilton. 2003. Energy translocation across cell membranes and membrane models. Acta Physiol. Scand. 178:357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cupp, D., J. P. Kampf, and A. M. Kleinfeld. 2004. Fatty acid-albumin complexes and the determination of the transport of long chain free fatty acids across membranes. Biochemistry. 43:4473–4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kampf, J. P., D. Cupp, and A. M. Kleinfeld. 2006. Different mechanisms of free fatty acid flip-flop and dissociation revealed by temperature and molecular species dependence of transport across lipid vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 281:21566–21574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas, R. M., A. Baici, M. Werder, G. Schulthess, and H. Hauser. 2002. Kinetics and mechanism of long-chain fatty acid transport into phosphatidylcholine vesicles from various donor systems. Biochemistry. 41:1591–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamp, F., W. Guo, R. Souto, P. F. Pilch, B. E. Corkey, and J. A. Hamilton. 2003. Rapid flip-flop of oleic acid across the plasma membrane of adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:7988–7995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baillie, A. G., C. T. Coburn, and N. A. Abumrad. 1996. Reversible binding of long-chain fatty acids to purified FAT, the adipose CD36 homolog. J. Membr. Biol. 153:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajri, T., X. X. Han, A. Bonen, and N. A. Abumrad. 2002. Defective fatty acid uptake modulates insulin responsiveness and metabolic responses to diet in CD36-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 109:1381–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmon, C. M., P. Luce, A. H. Beth, and N. A. Abumrad. 1991. Labeling of adipocyte membranes by sulfo-N-succinimidyl derivatives of long-chain fatty acids: inhibition of fatty acid transport. J. Membr. Biol. 121:261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luiken, J. J., Y. Arumugam, D. J. Dyck, R. C. Bell, M. M. Pelsers, L. P. Turcotte, N. N. Tandon, J. F. Glatz, and A. Bonen. 2001. Increased rates of fatty acid uptake and plasmalemmal fatty acid transporters in obese Zucker rats. J. Biol. Chem. 276:40567–40573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamp, F., and J. A. Hamilton. 2006. How fatty acids of different chain length enter and leave cells by free diffusion. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 75:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamp, F., and J. A. Hamilton. 1992. pH gradients across phospholipid membranes caused by fast flip-flop of un-ionized fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:11367–11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orosz, D. E., and K. D. Garlid. 1993. A sensitive new fluorescence assay for measuring proton transport across liposomal membranes. Anal. Biochem. 210:7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamp, F., J. A. Hamilton, F. Kamp, H. V. Westerhoff, and J. A. Hamilton. 1993. Movement of fatty acids, fatty acid analogues, and bile acids across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 32:11074–11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamp, F., D. Zakim, F. Zhang, N. Noy, and J. A. Hamilton. 1995. Fatty acid flip-flop in phospholipid bilayers is extremely fast. Biochemistry. 34:11928–11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartlett, G. R. 1959. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richieri, G. V., R. T. Ogata, and A. M. Kleinfeld. 1992. A fluorescently labeled intestinal fatty acid binding protein. Interactions with fatty acids and its use in monitoring free fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 267:23495–23501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richieri, G. V., R. T. Ogata, and A. M. Kleinfeld. 1999. The measurement of free fatty acid concentration with the fluorescent probe ADIFAB: a practical guide for the use of the ADIFAB probe. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 192:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wall, J., F. Ayoub, and P. O'Shea. 1995. Interactions of macromolecules with the mammalian cell surface. J. Cell Sci. 108:2673–2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo, W., N. Huang, J. Cai, W. Xie, and J. A. Hamilton. 2006. Fatty acid transport and metabolism in HepG2 cells. Am. J. Physiol. 290:G528–G534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meshulam, T., J. R. Simard, J. Wharton, J. A. Hamilton, and P. F. Pilch. 2006. Role of caveolin-1 and cholesterol in transmembrane fatty acid movement. Biochemistry. 45:2882–2893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reference deleted in proof.

- 24.Hamilton, J. A. 1995. 13C NMR studies of the interactions of fatty acids with phospholipid bilayers, plasma lipoproteins, and proteins. In Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy. N. Beckman, editor. Academic Press, San Diego. 117–157.

- 25.Asawakarn, T., J. Cladera, and P. O'Shea. 2001. Effects of the membrane dipole potential on the interaction of saquinavir with phospholipid membranes and plasma membrane receptors of Caco-2 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:38457–38463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cladera, J., I. Martin, J. M. Ruysschaert, and P. O'Shea. 1999. Characterization of the sequence of interactions of the fusion domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus with membranes. Role of the membrane dipole potential. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29951–29959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cladera, J., and P. O'Shea. 1998. Intramembrane molecular dipoles affect the membrane insertion and folding of a model amphiphilic peptide. Biophys. J. 74:2434–2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wall, J., C. A. Golding, M. Van Veen, and P. O'Shea. 1995. The use of fluorescein phosphatidylethanolamine (FPE) as a real-time probe for peptide-membrane interactions. Mol. Membr. Biol. 12:183–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richieri, G. V., R. T. Ogata, and A. M. Kleinfeld. 1995. Thermodynamics of fatty acid binding to fatty acid-binding proteins and fatty acid partition between water and membranes measured using the fluorescent probe ADIFAB. J. Biol. Chem. 270:15076–15084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper, R. B., N. Noy, and D. Zakim. 1989. Mechanism for binding of fatty acids to hepatocyte plasma membranes. J. Lipid Res. 30:1719–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massey, J. B., D. H. Bick, and H. J. Pownall. 1997. Spontaneous transfer of monoacyl amphiphiles between lipid and protein surfaces. Biophys. J. 72:1732–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jezek, P., M. Modriansky, and K. D. Garlid. 1997. Inactive fatty acids are unable to flip-flop across the lipid bilayer. FEBS Lett. 408:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richieri, G. V., and A. M. Kleinfeld. 1995. Unbound free fatty acid levels in human serum. J. Lipid Res. 36:229–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zakim, D. 2000. Thermodynamics of fatty acid transfer. J. Membr. Biol. 176:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stump, D. D., X. Fan, and P. D. Berk. 2001. Oleic acid uptake and binding by rat adipocytes define dual pathways for cellular fatty acid uptake. J. Lipid Res. 42:509–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamilton, J. A., V. N. Civelek, F. Kamp, K. Tornheim, and B. E. Corkey. 1994. Changes in internal pH caused by movement of fatty acids into and out of clonal pancreatic β-cells (HIT). J. Biol. Chem. 269:20852–20856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu, M. L., C. C. Chan, and M. J. Su. 2000. Possible mechanism(s) of arachidonic acid-induced intracellular acidosis in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 86:E55–E62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aires, V., A. Hichami, K. Moutairou, and N. A. Khan. 2003. Docosahexaenoic acid and other fatty acids induce a decrease in pHi in Jurkat T-cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 140:1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton, J. A., R. A. Johnson, B. Corkey, and F. Kamp. 2001. Fatty acid transport: the diffusion mechanism in model and biological membranes. J. Mol. Neurosci. 16:99–108 (discussion 151–107). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton, J. A., W. Guo, and F. Kamp. 2002. Mechanism of cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids: do we need cellular proteins? Mol. Cell. Biochem. 239:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abumrad, N., C. Coburn, and A. Ibrahimi. 1999. Membrane proteins implicated in long-chain fatty acid uptake by mammalian cells: CD36, FATP and FABPm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1441:4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coort, S. L., J. Willems, W. A. Coumans, G. J. van der Vusse, A. Bonen, J. F. Glatz, and J. J. Luiken. 2002. Sulfo-N-succinimidyl esters of long chain fatty acids specifically inhibit fatty acid translocase (FAT/CD36)-mediated cellular fatty acid uptake. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 239:213–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamilton, J. A. 2007. New insights into the roles of proteins and lipids in membrane transport of fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 77:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]