Abstract

Stochastic gene expression in bacteria can create a diverse protein distribution. Most of the current studies have focused on fluctuations around the mean, which constitutes the majority of a bacterial population. However, when the bacterial population is subject to a severe selection pressure, it is the properties of the minority cells that determine the fate of the population. The central question is whether phenotype heterogeneity, such as a spread in the expression level of a critical protein, is sufficient to account for the persistence of the bacteria under the selection. A related question is how long such persistence can last before genetic mutation becomes significant. In this work, survival statistics of a bacterial population with a diverse phage-receptor number distribution is theoretically investigated when the cells are subject to phage pressures. The calculations are compared with our experimental observations presented in Part I in this issue. The fundamental basis of our analysis is the Berg-Purcell theoretical result for the reaction rate between a phage particle and a bacterium with a discrete number of receptors, and the observation that most phage-resistant mutants isolated in laboratory cultures are defective in phage binding. It is shown that a heterogeneous bacterial population is significantly more fit compared to a homogeneous population when confronting a phage attack.

INTRODUCTION

Heterogeneity in protein expression among genetically homogeneous prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells is an important biological phenomenon and has recently become a major area of biomedical interest (1–4). Protein-level population heterogeneity has been shown to allow a minority of the bacterial cells to survive even in instances when a saturating amount of antibiotics has killed most cells in the population (5). From these studies, simple mathematical models have been developed to provide insight on how these bacterial populations respond to sudden environmental stresses (5–7). These models have focused on systems where there are only two states of the cells, either sensitive or insensitive to the stress. In this article, we theoretically investigate population dynamics of Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacterium and λ-phage when sensitivity of the bacteria to phage infection has a broad, continuous distribution. As discussed in the accompanying article, referred to as Part I, this continuous spectrum of susceptibility arises because phage adsorption depends on the number of λ-receptors (LamB) on the bacterium, and this number can fluctuate in time in a single cell and in different bacteria due to stochastic gene expression and cell division (8,9). The biological underpinning of such fluctuations is perhaps the stochastic gene expression and unequal partitioning of proteins during cell division. For a given phage pressure, defined as the number of initial phages per volume P(0), the bacteria with a high number of receptors are infected rapidly and are eliminated from the population whereas bacteria with a low number of receptors are less prone to infection and have the chance to multiply. The population dynamics is akin to a prey-predator model (10–12) but the process in this case is highly nonlinear; we note that even though only a single successful phage binding is required to infect a bacterium, the high-receptor-number cells are able to bind multiple phages and effectively alleviate the phage pressure for low-receptor-number cells. The latter population, therefore, is protected not only by virtue of its low binding rate but is also shielded by the high-receptor-number cells.

Based on our earlier phage adsorption studies (13), a mathematical model is constructed that incorporates essential features of phage infection, which includes the heterogeneity of LamB receptors in the bacterial population, the switching of bacteria from high (low) to low (high) receptor subpopulations, and multiplications of bacteria and phage. It is shown that the naïve homogeneous population model, which has been previously used for interpreting bacterium/phage population dynamics data (14), leads to bacterial extinction even for a moderate phage pressure. Including receptor heterogeneity can significantly improve the fitness of the bacterial population and allows it to persist under strong phage pressures. This robust bacterial response was found to be the case even when the phenotype switching is neglected in the population model. In this simple case, an analytical expression can be developed which shows that bacteria with high receptor numbers are decimated but those with low receptor numbers are able to grow for a wide range of phage pressures P(0). The critical receptor number nC that separates these two groups of cells is given by  where a and b are the major and the minor semi-axis of the bacterium, s is the radius of the receptor, D is the diffusion coefficient of the phage, and Λ is the growth rate of the bacterium. We found that the simplified model describes rather well the initial response of the bacterial population to various phage pressures, which we termed the “killing curve” in Part I (see this issue). Though our current measurements could not yield detailed information on phenotype switching, such as the switching rate and its dependence on the state of individual cells, several lines of evidence suggests that such phenotype switching does take place and is important for the bacterium/phage population dynamics. The switching appears to contribute to the appearance of a quasi-steady state of bacterial population in some intermediate timescales, where the bacterial growth rate is effectively zero for several generations, and to increase the threshold for bacterial extinction. Both of these effects cannot be accounted for by the heterogeneous model without phenotype switching. Our preliminary measurements further suggest that the switching process is rather slow, taking many generations for a bacterium to switch from a low receptor-number to a high receptor-number state under a severe phage pressure.

where a and b are the major and the minor semi-axis of the bacterium, s is the radius of the receptor, D is the diffusion coefficient of the phage, and Λ is the growth rate of the bacterium. We found that the simplified model describes rather well the initial response of the bacterial population to various phage pressures, which we termed the “killing curve” in Part I (see this issue). Though our current measurements could not yield detailed information on phenotype switching, such as the switching rate and its dependence on the state of individual cells, several lines of evidence suggests that such phenotype switching does take place and is important for the bacterium/phage population dynamics. The switching appears to contribute to the appearance of a quasi-steady state of bacterial population in some intermediate timescales, where the bacterial growth rate is effectively zero for several generations, and to increase the threshold for bacterial extinction. Both of these effects cannot be accounted for by the heterogeneous model without phenotype switching. Our preliminary measurements further suggest that the switching process is rather slow, taking many generations for a bacterium to switch from a low receptor-number to a high receptor-number state under a severe phage pressure.

In the following, a phenomenological theory motivated by the known interactions between bacterium and phage is presented. The population dynamic equation for the bacterial population composed of varying degrees of phage sensitivity, which we termed the “heterogeneous model”, is derived. It is shown that the equation can be reduced to the homogeneous one that was extensively used by earlier investigators (10–12,14). The heterogeneous model is sufficiently complex and its prediction is possible only via numerical integration. To understand the biological and physical basis of the model and its relation to the experiment, several approximations of varying degrees of rigor are explored and the results are compared with the measurements described in Part I in this issue.

MATHEMATICAL MODELING

Bacteria have developed a variety of natural defense mechanisms that target diverse steps of the phage life cycle, notably: blocking adsorption; preventing DNA injection; restricting incoming DNA; and having abortive infection systems. In this article, we investigate quantitatively the long-suspected scenario that the short-time persistence to phage infection occurs at the binding stage, the bacterium's first line of defense. We wish to show via systematic measurements and mathematical modeling that our observed behavior (the “killing curves”) can be accounted for by this single mechanism. Previous theoretical (15) and experimental works (13,16) have shown that the phage adsorption rate of a bacterium is a function of the number of receptors n on the bacterial cell wall,

|

(1) |

where γ∞ = 4πDa/ln(2a/b) is the adsorption rate for an ideal elliptical absorber whose entire surface is covered with receptors, D is the diffusion coefficient of the phage, and s(≈4 nm) is the radius of the receptor. This remarkable result was first derived by Berg and Purcell (15) and was later found to be valid essentially for a wide range of receptor coverage (17). The adsorption exhibits two different behaviors: For low receptor numbers, n ≪ n0(≡π(a/s)/ln(2a/b)), the rate constant is linear in n, γn ≈ γ1n, suggesting no interference between different receptors on phage binding, where γ1 = 4Ds is the adsorption rate of a single receptor on the bacterium. For high receptor numbers n ≫ n0, γn ≈ γ∞, which is independent of n. The existence of a linear crossover is by itself interesting as it suggests that even sparsely populated receptors are sufficient to achieve a high reaction rate. This surprising result can be shown to be a general property of diffusion, i.e., once a phage touches a surface, it has a high probability of probing the surface many times before leaving (13,15). Using parameters for the bacterial strain Ymel used in the experiment,  μm,

μm,  μm, and D = 7.6 × 10−8 cm2/s (see Section A in Supplementary Material, Data S1 in Part I), we found n0 to be ∼750, which is greater than the mean receptor number

μm, and D = 7.6 × 10−8 cm2/s (see Section A in Supplementary Material, Data S1 in Part I), we found n0 to be ∼750, which is greater than the mean receptor number  Very little is known about stochasticity of lamB expression in E. coli. However, judging from our flow cytometry data from Part I, it is evident that LamB fluctuates widely in different cells and under different growth conditions. Such wide cell-to-cell variations can create a broad spectrum of susceptibility to phage infection in a population. Our aim below is to show that bacterial survival statistics can, in part, be accounted for by the receptor number fluctuations.

Very little is known about stochasticity of lamB expression in E. coli. However, judging from our flow cytometry data from Part I, it is evident that LamB fluctuates widely in different cells and under different growth conditions. Such wide cell-to-cell variations can create a broad spectrum of susceptibility to phage infection in a population. Our aim below is to show that bacterial survival statistics can, in part, be accounted for by the receptor number fluctuations.

Model equations

Heuristically, the population dynamics of bacterium and phage is akin to prey and predator communities and may be mimicked as such by the Lotka-Volterra equation (18). However, because the interactions between the bacterium and phage are reasonably well known, a more detailed/realistic model can be constructed. Let us assume for the moment that bacterial population is homogeneous and that at a given time the bacteria can be divided into the sensitive population S and the infected (pre- and post-bursting) population I in the presence of a phage population P. The equations describing these three populations are determined by the second-order rate equations and are given by

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where Λ is the bacterial growth rate, γ is the phage adsorption rate, τ is the phage maturing time, ɛ(≤1/τ) is the infected-cell degradation rate, and m is the bursting size. In the above, we have assumed that the sensitive cells have a growth rate Λ that is independent of the phage pressure P(t) and that the adsorption is irreversible with γ given by Eq. 1 with n being the average number of receptors. In a previous theoretical study of E. coli and λ-phage population dynamics (14), a four-population model was proposed, where the infected cell population I was subdivided into pre- and post-bursting populations. It can be shown, however, that the four-population model is equivalent to our three-population model. For simplicity, in the following the three-population model will be used. Aside from ɛ, all the parameters in Eqs. 2–4 are known, and in principle it should allow detailed comparisons between theory and experiment. Indeed, such an attempt has been made in Rabinovitch (14), where the investigators found that under reasonable conditions, a limit cycle can exist and thus coexistence between bacterium and phage is feasible. However, our calculations indicate that coexistence between bacterium and phage requires a fine-tuning of the rate constants in Eqs. 2–4 and are thus not robust solutions of the population dynamics. Given the experimental conditions in our measurements, we found that the homogeneous model consistently yields extinction of the bacterial population even for a moderate P(0). To reconcile with the experimental observation, which show persistence of sensitive cells under large phage pressures, population heterogeneity of bacteria to phage infection are introduced. Specifically we consider number fluctuations of the LamB receptors, i.e., the bacteria with n receptors, having the same sensitivity to phage infection, are grouped together and designated as the subpopulation Bn, where 0 < n < Nmax. Within each subpopulation, the bacteria are further classified into sensitive cells Sn and infected cells In, similar to the homogeneous model. The number conservation law then dictates the following set of equations must hold,

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

where γn is the adsorption coefficient given by Eq. 1, αmn is the switching rate from subpopulation n to subpopulation m, and the prime in the sum indicates that m = n is excluded. The switching between the subpopulations arises due to insertion or decay of receptors on the cell wall and due to partitioning of receptors during cell division. A schematic drawing depicting different bacterial subpopulations is given in Fig. 1. It is useful to point out certain limitations of our model. First of all, it is assumed that the growth rate Λ for different bacterial subpopulations is the same. This assumption is consistent with the observation that in the presence of a moderate amount of maltose or glucose, which is the case in the current experiment, the receptor number n is not the limiting factor for cell growth (19). In the special case of maltose-limiting media, the n-dependent growth rate can be taken into account by changing Λ to Λn, where Λn is also expected to depend on n as in Eq. 1. Second, the equations assume the carrying capacity of the medium is infinite, which is reasonable for the current experiment because our killing curves were measured in ∼10 h, and the overall bacterial concentration is well below saturation (∼109 cm−3) during measurements. Equations 5–7 are complicated since they consist of 2(Nmax+1) equations with many rate constants, such as αmn, being unknown. However, since our measurement is only sensitive to total uninfected bacteria  by counting colonies on agar plates, Eq. 1 can be significantly simplified. Summing on both sides of Eq. 5 and recognizing that the switching terms cancel,

by counting colonies on agar plates, Eq. 1 can be significantly simplified. Summing on both sides of Eq. 5 and recognizing that the switching terms cancel,

|

(8) |

Equation 5 now reads  We next define an ensemble-averaged adsorption rate

We next define an ensemble-averaged adsorption rate  which is time-dependent. The population dynamic equation for the sensitive bacteria is finally given by

which is time-dependent. The population dynamic equation for the sensitive bacteria is finally given by

|

(9) |

The equations for the infected cells and the free phage population can be similarly derived with the result

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

where  is the average adsorption coefficient of the infected cell population. We have thus shown that it is feasible to reduce the 2(Nmax+1) equations to merely three equations, and most significantly, the new equations have no explicit switching dependence. The cost of such simplification, however, is the appearance of the time-dependent adsorption constant γ(t). We noticed that Eqs. 9–11 are identical to the homogeneous model, Eqs. 2–4, if the time-dependent adsorption rates are set to a constant

is the average adsorption coefficient of the infected cell population. We have thus shown that it is feasible to reduce the 2(Nmax+1) equations to merely three equations, and most significantly, the new equations have no explicit switching dependence. The cost of such simplification, however, is the appearance of the time-dependent adsorption constant γ(t). We noticed that Eqs. 9–11 are identical to the homogeneous model, Eqs. 2–4, if the time-dependent adsorption rates are set to a constant  This illustrates the similarity as well as the fundamental differences between the two models, and calls into question the very assumption that interaction parameters and rate constants are time-independent in early models of population dynamics. Although the switching terms do not appear explicitly in Eq. 9, as we will show below, bacterial switching from one subpopulation to another is an important dynamic attribute and is relevant for a quantitative understanding of bacterium/phage populations as a function of time. However, we will also show that even in its absence (αmn = 0), the heterogeneous model already yields robust responses for the bacteria population to different phage pressures, and it can mimic the killing curves more closely than the homogeneous model.

This illustrates the similarity as well as the fundamental differences between the two models, and calls into question the very assumption that interaction parameters and rate constants are time-independent in early models of population dynamics. Although the switching terms do not appear explicitly in Eq. 9, as we will show below, bacterial switching from one subpopulation to another is an important dynamic attribute and is relevant for a quantitative understanding of bacterium/phage populations as a function of time. However, we will also show that even in its absence (αmn = 0), the heterogeneous model already yields robust responses for the bacteria population to different phage pressures, and it can mimic the killing curves more closely than the homogeneous model.

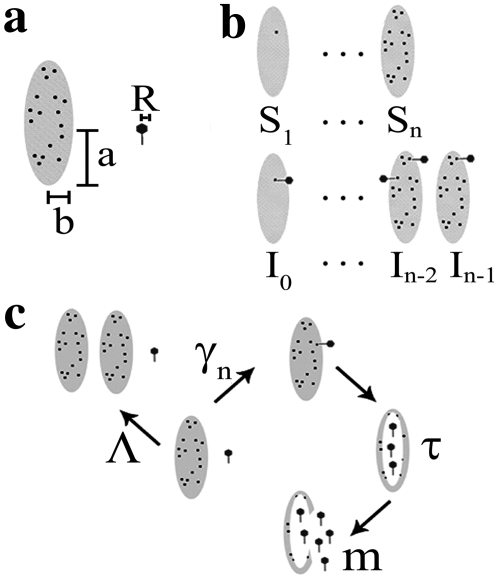

FIGURE 1.

(a) The drawing depicts the parameters of the bacteria and phage used to determine the adsorption coefficient. (b) The subpopulation of sensitive bacteria with n receptors is labeled as Sn, and the subpopulation of infected bacteria that have n available free receptors is labeled as In. (c) The life cycles of bacterium and phage. Uninfected or sensitive bacteria will multiply at a rate Λ. They adsorb phage at a rate γn, which depends on the receptor number n. Infected bacterium cannot multiply but can adsorb more phage with the rate determined by their available free receptors. After a latent period τ, the infected bacteria will burst, releasing m phage into the environment.

Approximate solutions to the model equations

Without the switching terms, Eqs. 5–7 can be integrated numerically for the given initial bacterial distribution Sn(0) = Bn(0), which we determined by the flow cytometry measurements. Here the only unknown is the receptor degradation rate ɛ, which is treated as an adjustable parameter. A fourth-order Runge-Kutta algorithm from Numerical Recipes in C was implemented in the numerical integration (20). The detailed comparison between the numerical method and our experimental results is presented in the next section.

Although numerical integration of Eqs. 5–7 is straightforward when αmn = 0, it is difficult to gain insights about the biological/physical processes governing the dynamics of the heterogeneous population. Considerable progress can be made, however, if one assumes that the phage population remains constant P(t) = P(0) = Po. Such an assumption allows the sensitive bacterial populations Sn(t) in Eq. 5 to be decoupled from the rest of the populations, i.e., Eqs. 6 and 7, making analytical analyses possible. The assumption of constant phage pressure, though not generally satisfied in our measurements, is valid under certain limiting conditions, such as for very short-time population dynamics  when phage are not significantly depleted by adsorption, and for very high phage concentrations

when phage are not significantly depleted by adsorption, and for very high phage concentrations  as if a phage reservoir were present. Under these conditions, the term Λ−γnPo is constant and each sensitive bacterial subpopulation obeys the simple equation

as if a phage reservoir were present. Under these conditions, the term Λ−γnPo is constant and each sensitive bacterial subpopulation obeys the simple equation

|

(12) |

We noted that without phenotype switching, Sn(t) is either growing or decaying exponentially depending on whether the effective growth rate Λeff = Λ−γnPo is positive or negative. For a given Po, one can define the critical receptor number nC such that for those subpopulations with n > nC, Sn(t) decays with time whereas for those subpopulations with n < nC, Sn(t) increases with time. Here nC is given by

|

(13) |

which is plotted in Fig. 2. One observes that nC increases sharply as Po is decreased. Since the maximum number of receptors is approximately a thousand, this calculation shows that for Po < 5 × 106 cm−3, essentially all bacterial subpopulations grow exponentially. Such peculiar behavior can be understood by the fact that for  the adsorption rate γn becomes independent of n and a minimal phage concentration ∼5 × 106 cm−3 is required to have a noticeable effect on bacterial growth. It is also interesting to calculate the phage pressure that is required to inhibit growth of the n = 1 subpopulation. Using Eq. 13, we found that when nC = 1, Po ≈ 3 × 109 cm−3, which is surprisingly close to the mutant selection limit Po ∼ 1010 cm−3 found in our Part I.

the adsorption rate γn becomes independent of n and a minimal phage concentration ∼5 × 106 cm−3 is required to have a noticeable effect on bacterial growth. It is also interesting to calculate the phage pressure that is required to inhibit growth of the n = 1 subpopulation. Using Eq. 13, we found that when nC = 1, Po ≈ 3 × 109 cm−3, which is surprisingly close to the mutant selection limit Po ∼ 1010 cm−3 found in our Part I.

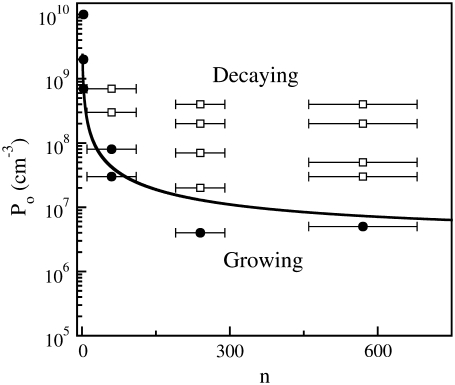

FIGURE 2.

The life-and-death of bacterial subpopulations with n receptors subjected to different phage pressures Po. The figure depicts the threshold value for a bacterial subpopulation with n receptors to grow or to decay. For Po above the line, the population decays but for Po below the line, the population grows. The threshold values are calculated based on the experimental parameters for Ymel, which are listed in Table 1 of Part I. This threshold curve matches rather well with the experimentally measured short-time (when  approximately constant) growth and decay rates for Ymel and LE392 populations when Po and n are varied systematically. As discussed in the main text, the initial behavior of a heterogeneous population is equivalent to a homogeneous one characterized by the mean receptor number

approximately constant) growth and decay rates for Ymel and LE392 populations when Po and n are varied systematically. As discussed in the main text, the initial behavior of a heterogeneous population is equivalent to a homogeneous one characterized by the mean receptor number  In the figure, the circles (squares) correspond to population growth (decay) for various combinations of Po and

In the figure, the circles (squares) correspond to population growth (decay) for various combinations of Po and  Different

Different  in the experiment were obtained by growing LE392 bacteria in different media.

in the experiment were obtained by growing LE392 bacteria in different media.

An interesting feature of Eq. 13 is that it is independent of the bacterial concentration, implying that this criterion is necessary but may not be sufficient for inhibiting bacterial growth for the entire population. To inhibit bacterial growth, including those with only one receptor, it also requires that for each receptor, at least one free phage is available for binding. This additional condition  turns out to be identical to the presence of a phage reservoir (or the constant P condition) discussed above. This relation can be cast into a simpler form:

turns out to be identical to the presence of a phage reservoir (or the constant P condition) discussed above. This relation can be cast into a simpler form:  or MOI(≡ P(0)/S(0)) ≫

or MOI(≡ P(0)/S(0)) ≫  For instance, for Po ≈ 3 × 109 cm−3 and

For instance, for Po ≈ 3 × 109 cm−3 and  S(0) must ≪107 cm−3 for the constant-P assumption to be valid. As we will see below, this condition is satisfied in some but not all of our measurements. When the above constant-P condition is supplemented with the kinetic requirement P(t) γ1 > Λ, one obtains the sufficient condition for decimating the entire sensitive population: P(t) > max(

S(0) must ≪107 cm−3 for the constant-P assumption to be valid. As we will see below, this condition is satisfied in some but not all of our measurements. When the above constant-P condition is supplemented with the kinetic requirement P(t) γ1 > Λ, one obtains the sufficient condition for decimating the entire sensitive population: P(t) > max( Λ/γ1). For practical reasons, such as in mutant selection or perhaps in future phage therapy, this relation provides a useful guide for experiment or treatment designs.

Λ/γ1). For practical reasons, such as in mutant selection or perhaps in future phage therapy, this relation provides a useful guide for experiment or treatment designs.

We next calculate the time-dependent bacterial population in the presence of a constant phage pressure and examine the effect of receptor distribution on the fitness of the bacterial population as a whole. This can be done by summing over all subpopulations Sn(t) given by Eq. 12,

|

(14) |

To illustrate the effect of receptor number fluctuations on the fitness, we used the Gaussian function for the receptor distribution

|

(15) |

where H(n) is the Heaviside step function and p(n) is properly normalized for n ≥ 0. The Gaussian distribution is rare in biological systems but has been observed in systems when proteins are expressed at very high levels (21,22). A full treatment using a log-normal distribution, which is closer to our experimental observations, is given in Section A in Data S1. Changing the summation in Eq. 14 to an integral and assuming γn = γ1n, which is a good approximation when  is ≪n0, S(t) can be calculated by a straightforward integration,

is ≪n0, S(t) can be calculated by a straightforward integration,

|

(16) |

where erfc(x) is the complementary error function, which is a monotonically decreasing function of x and has the following limits: erfc(x→−∞) = 2 and erfc(x→∞) = 0. The behavior of S(t) is thus determined predominantly by the exponential function for short and intermediate times. However, for long times, erfc(x) becomes important and S(t→∞) ∝ exp(Λt)/t. One finds that in the absence of receptor-number fluctuations, σ = 0, S(t) is the solution for a homogeneous population, which has an effective growth exponent  that can be either positive or negative depending on the phage pressure Po and

that can be either positive or negative depending on the phage pressure Po and  The receptor-number fluctuations (σ ≠ 0) always favor the recovery of the bacterial population, but its effect only takes place at an intermediate time because of its quadratic t dependence. For a declining bacterial population, Λeff = 0, the recovery occurs when

The receptor-number fluctuations (σ ≠ 0) always favor the recovery of the bacterial population, but its effect only takes place at an intermediate time because of its quadratic t dependence. For a declining bacterial population, Λeff = 0, the recovery occurs when  In the presence of a strong phage pressure,

In the presence of a strong phage pressure,  showing recovery occurs earlier for a broader receptor distribution. Useful information can also be extracted in the short-time limit t ≪ τ, where one can find the average number of receptors

showing recovery occurs earlier for a broader receptor distribution. Useful information can also be extracted in the short-time limit t ≪ τ, where one can find the average number of receptors  by plotting Λeff versus Po. The slope of such a plot yields

by plotting Λeff versus Po. The slope of such a plot yields  (or

(or  ) and the intercept is the unperturbed growth rate Λ. The above calculation, though very simplified, illustrates the importance of receptor-number fluctuations on the survival or the fitness of the bacterial population.

) and the intercept is the unperturbed growth rate Λ. The above calculation, though very simplified, illustrates the importance of receptor-number fluctuations on the survival or the fitness of the bacterial population.

Comparisons between theory and experiment

In the following, theoretical expressions developed above are compared with measurements. This allows us to evaluate the validity as well as the weaknesses of certain assumptions made in the model. More importantly, it allows us to gain insight about the phenotype switching, which while difficult to model, is biologically significant.

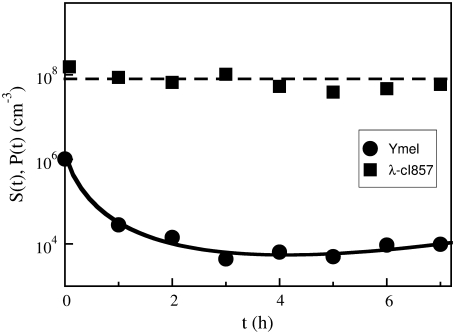

Killing curves with P approximately constant

We first examine the killing-curve under the assumption of constant P and no phenotype switching αmn = 0. In this case, S(t) in Eq. 14 only depends on the initial receptor distribution p(n) = Sn(0)/S(0). To satisfy the condition P(t) ≈ Po, we compared calculations with measurements carried out at a large phage concentration Po ∼ 1.5 × 108 cm−3 and a relatively small bacterial concentration S(0) ∼ 106 cm−3. A typical measurement for Ymel is displayed in Fig. 3, where the circles are for S(t) and the squares are for P(t). We note that though  is not strictly obeyed, the MOI is sufficiently large to render P(t) approximately constant over the span of 7 h. During this time interval, S(t) plummeted by nearly two orders of magnitude. The solid line in the figure is the fit to the theoretical expression given in Data S1, where p(n) is assumed to be log-normally distributed. The fitting procedure yields the mean

is not strictly obeyed, the MOI is sufficiently large to render P(t) approximately constant over the span of 7 h. During this time interval, S(t) plummeted by nearly two orders of magnitude. The solid line in the figure is the fit to the theoretical expression given in Data S1, where p(n) is assumed to be log-normally distributed. The fitting procedure yields the mean  and the standard deviation

and the standard deviation  for the log-normal distribution. Based on this distribution, the normal mean

for the log-normal distribution. Based on this distribution, the normal mean  and the standard deviation

and the standard deviation  can be calculated. Averaging over seven separate runs, we found

can be calculated. Averaging over seven separate runs, we found  and σ = 320 ± 30. Five similar measurements were also performed for LE392, resulting in

and σ = 320 ± 30. Five similar measurements were also performed for LE392, resulting in  and σ = 610 ± 130. We found that while

and σ = 610 ± 130. We found that while  obtained above is reasonably consistent with the flow cytometry measurements (see Table 1 for more details), σ is nearly a factor-of-two greater for both strains of bacteria. The discrepancy is in part due to the fact that the lower end of the p(n) determined by flow cytometry cannot be accurately mimicked by the simple log-normal function (see Fig. 2 c in Part I), and in part due to the presence of switching in the bacterial subpopulations; a subject we will come back to below. Both of these factors conspire to give an artificially large σ and make the assumptions used to derive the analytic model only valid at short times, a subject investigated later in this article. However, considering the simplicity of the analytic model, the agreement between the calculation and the measurements is fair.

obtained above is reasonably consistent with the flow cytometry measurements (see Table 1 for more details), σ is nearly a factor-of-two greater for both strains of bacteria. The discrepancy is in part due to the fact that the lower end of the p(n) determined by flow cytometry cannot be accurately mimicked by the simple log-normal function (see Fig. 2 c in Part I), and in part due to the presence of switching in the bacterial subpopulations; a subject we will come back to below. Both of these factors conspire to give an artificially large σ and make the assumptions used to derive the analytic model only valid at short times, a subject investigated later in this article. However, considering the simplicity of the analytic model, the agreement between the calculation and the measurements is fair.

FIGURE 3.

A killing curve with a constant phage pressure. The circles are for Ymel population S(t) measured in CFU/cm3 and the squares are for the phage concentration P(t) measured in PFU/cm3. The solid line is the fit to the log-normal receptor distribution using Eq. S5 in Data S1. More than three curves such as this one were fit and the resulting  and σ are listed in Table 1.

and σ are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Mean and standard deviation of the receptor distribution

| Log-normal fits

|

Short-time fits

|

Flow cytometry

|

Fluorometry

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

σn |  |

σn |  |

σn |  |

|

| LE392 | 600 ± 120 | 610 ± 130 | 618 ± 140 | 215 ± 25 | 570 ± 50 | 200 ± 10 | 550 ± 80 |

| Ymel | 310 ± 20 | 320 ± 30 | 177 ± 23 | 105 ± 8 | 240 ± 30 | 140 ± 60 | 270 ± 30 |

The average receptor number  and its standard deviation σn were obtained using four different methods: fitting to the early- and the intermediate-time killing data using the saddle-point approximation (the log-normal fits); fitting to the early killing data; using data from flow cytometry; and from fluorometry. The

and its standard deviation σn were obtained using four different methods: fitting to the early- and the intermediate-time killing data using the saddle-point approximation (the log-normal fits); fitting to the early killing data; using data from flow cytometry; and from fluorometry. The  for both LE392 and Ymel strains was also estimated using microscope measurements (data not shown) and was found to be consistent with the results obtained from fluorometry and in flow cytometry. While

for both LE392 and Ymel strains was also estimated using microscope measurements (data not shown) and was found to be consistent with the results obtained from fluorometry and in flow cytometry. While  is in generally good agreement between different measurements, σn has large variations. In particular, the log-normal fit yields anomalously big σn, which we discussed in the main text.

is in generally good agreement between different measurements, σn has large variations. In particular, the log-normal fit yields anomalously big σn, which we discussed in the main text.

Killing curves without the constant-P assumption

In the more general case, the phage concentration P is not constant due to phage adsorption and production. Thus, it is of interest to examine the situation where the constant-P assumption is relaxed, but the switching terms are still suppressed αmn = 0. The population dynamics characterized by Eqs. 5–7 were numerically integrated using the flow cytometry data in Part I as the initial condition for each subpopulation Sn and the results are presented in Fig. 4, b, e, and h, for Ymel, induced LE392, and uninduced LE392, respectively. Other relevant parameters for the calculations were summarized in Table 1 of Part I, except for ɛ. Biologically, ɛ−1 is the LamB degradation time, which should be long compared to the bacterial lysis time, i.e., ɛ−1 ≥ τ. In the numerical integration, ɛ was varied over a broad range, and the features of the killing curve were found to be insensitive to large changes in ɛ. Hence, ɛ was fixed at τ−1. For comparison, the dynamic equations for a homogeneous population, Eqs. 2–4, were also numerically integrated using the average receptor numbers,  and 2, for Ymel, induced LE392, and uninduced LE392, respectively. The results for the homogeneous model are presented respectively in Fig. 4, c, f, and i, for the two strains of bacteria. In all calculations, S(0) and P(0) were given according to the experimental conditions in Fig. 4, a, d, and g. Namely, the colors of the individual curves in the calculations match that of the measurements.

and 2, for Ymel, induced LE392, and uninduced LE392, respectively. The results for the homogeneous model are presented respectively in Fig. 4, c, f, and i, for the two strains of bacteria. In all calculations, S(0) and P(0) were given according to the experimental conditions in Fig. 4, a, d, and g. Namely, the colors of the individual curves in the calculations match that of the measurements.

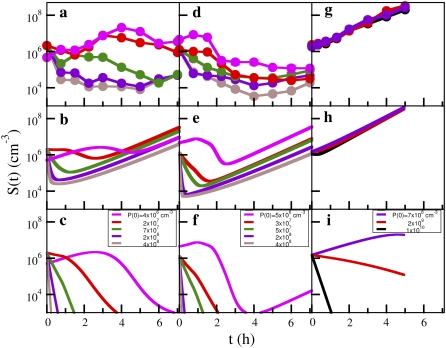

FIGURE 4.

Comparison between simulations and experimental killing curves without the constant-P assumption. The initial bacterial concentration is B(0) ≈ 106 cm−3 and is approximately the same for all runs. The curves in panel a are for Ymel with P(0) = 4 × 106 (pink), 2 × 107 (red), 7 × 107 (green), 2 × 108 (purple), and 4 × 108 cm−3 (brown). The simulations using the heterogeneous model (Eqs. 5–7) and the homogeneous model (Eqs. 2–4) are displayed respectively in panels b and c for the corresponding P(0) used in the experiment. The curves in panel d are for induced LE392 with P(0) = 5 × 106 (pink), 3 × 107 (red), 5 × 107 (green), 2 × 108 (purple), and 4 × 108 cm−3 (brown). The simulations using the heterogeneous model and the homogeneous model are displayed respectively in panels e and f for the corresponding P(0) used in the experiment. The curves in panel g are for uninduced LE392 with P(0) = 7 × 108 cm−3 (purple), P(0) = 2 × 109 cm−3 (red), and P(0) = 1010 cm−3. The simulations using the heterogeneous model and the homogeneous model are displayed, respectively, in panels h and i for the corresponding P(0) used in the measurement. The relevant parameters used in the simulations are given in Table 1 of Part I. For uninduced LE392 bacteria, which were grown in M9+glucose, we used Λ = 1.3 h−1 and m = 30, which were determined by experiment.

The experimental results and model calculations for the uninduced LE392 bacteria are presented in Fig. 4, g–i. They are an example of persistence in the extreme form when a large percentage of the population is persistent against phage infection. There exists a critical phage pressure defined as  For

For  and when the increased growth rate Λ = 1.3 h−1 for cells grown in M9+glucose was taken into account, we found PC(0) = 2 × 109 cm−3. This critical point has a large effect on the simulation of the homogeneous model as seen in Fig. 4 i, where three distinctive behaviors (growth, slow decay, and fast decay) are observed depending on whether P(0) is greater than or less than PC(0). However, this strong P(0) dependence was not observed in the experiment as displayed in Fig. 4 g nor predicted by the heterogeneous model as displayed in Fig. 4 h. For the heterogeneous model, when P(0) > PC(0), only a slight decrease in the growth rate in early times was observed, which is delineated by the black line in Fig. 4 h. The system very quickly recovers and resumes the exponential growth. Overall, the heterogeneous model mimics very well the experimental observation for all P(0) used in the measurement.

and when the increased growth rate Λ = 1.3 h−1 for cells grown in M9+glucose was taken into account, we found PC(0) = 2 × 109 cm−3. This critical point has a large effect on the simulation of the homogeneous model as seen in Fig. 4 i, where three distinctive behaviors (growth, slow decay, and fast decay) are observed depending on whether P(0) is greater than or less than PC(0). However, this strong P(0) dependence was not observed in the experiment as displayed in Fig. 4 g nor predicted by the heterogeneous model as displayed in Fig. 4 h. For the heterogeneous model, when P(0) > PC(0), only a slight decrease in the growth rate in early times was observed, which is delineated by the black line in Fig. 4 h. The system very quickly recovers and resumes the exponential growth. Overall, the heterogeneous model mimics very well the experimental observation for all P(0) used in the measurement.

Let us focus on the more subtle case of bacteria expressing a higher level of LamB, such as Ymel in Fig. 4 b and induced LE392 bacteria in Fig. 4 e. Different behaviors emerge in short times for these cells depending on P(0). For a low P(0), the bacterial population S(t) initially grows with a positive growth rate Λeff that decreases with P(0). For a high P(0), S(t) decreases and Λeff is negative. As shown in these figures, it is feasible to adjust P(0) such that Λeff is nearly zero, indicating a rough balance between the killing and the reproduction of bacteria in short times. Over a longer timescale, S(t) evolves in a more complicated fashion for low P(0) than for high P(0); it increases in size for a period of time, follows a period of decline, and then increases again. The late-time growth rate is approximately equal to Λ, indicating that those prospering bacteria have small number of n and their growth is largely unaffected by the presence of phage. The ups-and-downs in S(t) over time are due to the multiplication of phage particles that alters the phage pressure P(t) in the sample. In other words, these features will be absent if P(t) is held constant. Such a phage perturbation is less noticeable when P(0) is large initially. In this case, S(t) always decreases in early times and then increases in the later time. The crossover from the early- to the late-time behavior becomes shorter as P(0) increases as is expected based on the saddle-point analysis discussed above (see also Data S1). The above highly nonlinear features predicted by the heterogeneous population model mimics qualitatively the experimental observations displayed in Fig. 4, a and d. Quantitatively, however, the simulation and the measurements show noticeable differences, particularly the slow recovery in S(t) when P(0) is large. We wish to address this important feature later in the article.

We now turn our attention to the theoretical predictions for homogeneous bacterial populations, which are presented in Fig. 4, c and f, for Ymel and induced LE392, respectively. Here, one observes that as far as the short-time behavior is concerned, the homogeneous model makes reasonable predictions about when the bacterial population is growing (or decaying) when P(0) is varied. The predicted magnitude of Λeff is also consistent with the above more detailed calculations. For instance, for Ymel with  the critical phage concentration is predicted to be PC(0) ∼ 2 × 107 cm−3, and for induced LE392 with

the critical phage concentration is predicted to be PC(0) ∼ 2 × 107 cm−3, and for induced LE392 with  PC(0) = 8 × 106 cm−3. These simple, quantitative features were indeed supported by extensive measurements as delineated in Fig. 2. Here the data points represent bacterial populations that are initially growing (circles) or decaying (squares), and the boundary between the two sets of data are well represented by the theoretical prediction, Eq. 13, which is plotted as the line. This observation leaves shows the population heterogeneity and fluctuations in P(t) are insignificant in predicting the short-time population dynamics. This can be understood by the fact that the short-time response of S(t) is mostly due to the majority cell population, which is equivalent to a homogeneous population characterized by the mean receptor number

PC(0) = 8 × 106 cm−3. These simple, quantitative features were indeed supported by extensive measurements as delineated in Fig. 2. Here the data points represent bacterial populations that are initially growing (circles) or decaying (squares), and the boundary between the two sets of data are well represented by the theoretical prediction, Eq. 13, which is plotted as the line. This observation leaves shows the population heterogeneity and fluctuations in P(t) are insignificant in predicting the short-time population dynamics. This can be understood by the fact that the short-time response of S(t) is mostly due to the majority cell population, which is equivalent to a homogeneous population characterized by the mean receptor number  that remains approximately constant during the measurements. Since in short time there is no significant phage production or adsorption, P(t) also remains nearly constant. A conspicuous but disturbing feature of the homogenous model is the late-time behavior, where even with a moderate P(0), the sensitive bacteria suffer a rapid decline in the population size. It is clear that the homogeneous population lacks the plasticity to cope with the phage pressure, and it becomes extinct quickly under most of our experimental conditions. For a low phage pressure, however, recovery, oscillations, or even a steady-state solution were found to be feasible, but this requires fine tuning of the model parameters and thus cannot represent the true dynamics of our bacterium/phage system.

that remains approximately constant during the measurements. Since in short time there is no significant phage production or adsorption, P(t) also remains nearly constant. A conspicuous but disturbing feature of the homogenous model is the late-time behavior, where even with a moderate P(0), the sensitive bacteria suffer a rapid decline in the population size. It is clear that the homogeneous population lacks the plasticity to cope with the phage pressure, and it becomes extinct quickly under most of our experimental conditions. For a low phage pressure, however, recovery, oscillations, or even a steady-state solution were found to be feasible, but this requires fine tuning of the model parameters and thus cannot represent the true dynamics of our bacterium/phage system.

The above model calculations leave little doubt that population heterogeneity is a significant attribute for a bacterial population to evade phage attack for long times, i.e., over many generations of bacterial replications. The fact that most of these surviving bacteria, when regrown in a phage-free environment, recover their ability to adsorb phage, rules out the possibility of genetic mutation to be the cause of phage resistance seen in our experiment. For the initial bacterial population size S(0) ∼ 106 cm−3, which is used in most of our measurements as displayed in Fig. 4, mutants must be generated at timescales much longer than our measurement time ∼12 h. Our experiment thus supports the scenario that such coexistence is maintained by a group of bacteria that express receptors at a very low level such that their growth rate is not significantly affected by the presence of phage.

The effect of phenotype switching

The above discussion gives the impression that switching between bacterial subpopulations may not be significant since, even in its absence (αmn = 0), the simplified model (Eqs. 5–7) already captures essential features of the killing curves. In this section, however, we would like to show based on several lines of evidence that phenotype switching between subpopulations must exist, and that it plays a subtle but important role for bacterium/phage population dynamics.

A conspicuous feature of the killing curves in Fig. 4, a and d, is the broad minima seen in S(t) when a relatively large phage pressure P(0) >108 cm−3 is present. The broad minimum can span the time interval between 1 and 6 h after the phage is introduced. This behavior cannot be accurately accounted for by the dynamic equations without the switching terms as indicated by the simulated curves in Fig. 4, b and e. Here, we found that S(t) recovers rather rapidly after the initial killing. Moreover, although the broad minimum seen in Fig. 3 was mimicked by the saddle-point approximation, to produce a good fit, the width of the receptor distribution σ was found to be twice as large as observed in the flow cytometry measurement. The broadened distribution exaggerates the size of the minority subpopulation; that is, to account for the very slow dynamics, it requires more minority cells with smaller n than are actually present in the bacterial population. We believe these discrepancies between theory and experiment are all stemmed from the inappropriate treatment of switching in the calculation. Indeed, as shown in Part I, in the presence of a very high P(0) > 1010 cm−3 when all cells with finite n were expected to be decimated, we observed that the killing curves become independent of P(0). In this extreme case, the killing curve can be interpreted as a slow leakage of cells from n = 0 to n ≠ 0 states, and such a leakage appears to depend on whether the maltose operon is induced or not.

It should be kept in mind that since S(t) is a sum over the bacterial subpopulations, it cannot provide direct information about how individual subpopulations react to P(0) and how they switch. A quantity that is more closely related to the switching dynamics is the average adsorption rate  of sensitive cells, which may give us a closer look at the switching dynamics because

of sensitive cells, which may give us a closer look at the switching dynamics because  reflects dynamics in the receptor space. According to Eq. 9, the time-dependent S(t) and P(t) allow us to calculate

reflects dynamics in the receptor space. According to Eq. 9, the time-dependent S(t) and P(t) allow us to calculate  a function of time:

a function of time:

|

(18) |

It should be emphasized that Eq. 9 was derived under the most general situation and consequently  derived using Eq. 18 is free of both the constant-P and no switching (αmn= 0) assumptions. Using the killing curve in Fig. 4 a, where both S(t) and P(t) were measured frequently in short time intervals, we were able to calculate

derived using Eq. 18 is free of both the constant-P and no switching (αmn= 0) assumptions. Using the killing curve in Fig. 4 a, where both S(t) and P(t) were measured frequently in short time intervals, we were able to calculate  using a cubic spline-interpolation method (20). The knowledge of P(t) then allowed us to estimate the average adsorption rate constant

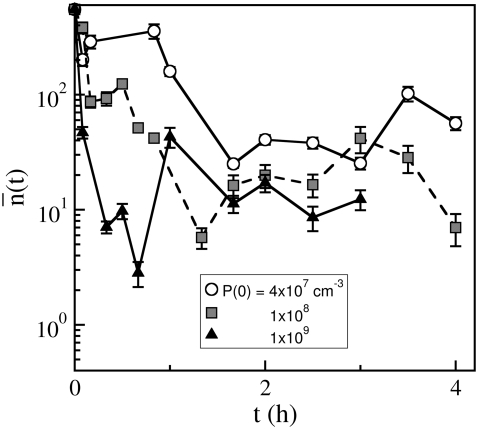

using a cubic spline-interpolation method (20). The knowledge of P(t) then allowed us to estimate the average adsorption rate constant  as a function of time. Fig. 5 is a plot of

as a function of time. Fig. 5 is a plot of  vs. t for three different initial phage concentrations P(0) = 1 × 109 (triangles), 1 × 108 (squares), and 4 × 107 cm−3 (circles). Although the measurements are noisy, certain trends exist when P(0) is varied. One observes that initially

vs. t for three different initial phage concentrations P(0) = 1 × 109 (triangles), 1 × 108 (squares), and 4 × 107 cm−3 (circles). Although the measurements are noisy, certain trends exist when P(0) is varied. One observes that initially  decreases with time, and the rate of decrease is enhanced as P(0) increases. Moreover, the level of

decreases with time, and the rate of decrease is enhanced as P(0) increases. Moreover, the level of  after several generations (t >2 h) appears to depend on P(0); it is

after several generations (t >2 h) appears to depend on P(0); it is  for P(0) = 4 × 107 cm−3 and ∼10 for P(0) ∼ 109 cm−3. We found in this intermediate-time regime, the condition

for P(0) = 4 × 107 cm−3 and ∼10 for P(0) ∼ 109 cm−3. We found in this intermediate-time regime, the condition  is approximately satisfied, indicating that both n(t) and S(t) can reach a quasi-steady state simultaneously.

is approximately satisfied, indicating that both n(t) and S(t) can reach a quasi-steady state simultaneously.

FIGURE 5.

Time-dependent adsorption rate constant of the sensitive bacterial population. The  decreases with t when the phage pressure is applied. Here

decreases with t when the phage pressure is applied. Here  was calculated using Eq. 1 based on measurements of S(t) and P(t). The three curves correspond to P(0) = 1 × 109 (triangles), 1 × 108 (squares), and 4 × 107 cm−3 (circles). The bacterial concentration B(0) = 3 × 107 cm−3 was the same for all runs.

was calculated using Eq. 1 based on measurements of S(t) and P(t). The three curves correspond to P(0) = 1 × 109 (triangles), 1 × 108 (squares), and 4 × 107 cm−3 (circles). The bacterial concentration B(0) = 3 × 107 cm−3 was the same for all runs.

The fact that  or

or  or does not plummet to zero under a high phage pressure (MOI ≫ 1) is revealing, and it implies phenotype switching between subpopulations. By the definition of

or does not plummet to zero under a high phage pressure (MOI ≫ 1) is revealing, and it implies phenotype switching between subpopulations. By the definition of  it can be shown that the rate of change of

it can be shown that the rate of change of  is given by

is given by

|

(19) |

The first term in the above equation can be calculated using Eq. 5 with the result

|

(20) |

where  and the over-bar is the average according to the distribution p(n,t) = Sn(t)/S(t). Physically,

and the over-bar is the average according to the distribution p(n,t) = Sn(t)/S(t). Physically,  represents the mean spreading rate in the receptor space. It is evident that in the absence of a phage pressure

represents the mean spreading rate in the receptor space. It is evident that in the absence of a phage pressure  because p(n,t) is time-invariant. On the other hand, when P(0) ≠ 0, preferential killing causes

because p(n,t) is time-invariant. On the other hand, when P(0) ≠ 0, preferential killing causes  to be more heavily weighed for small n than for large n, giving rise to

to be more heavily weighed for small n than for large n, giving rise to  Since

Since  substituting Eq. 20 into Eq. 19, we finally arrive at the relation

substituting Eq. 20 into Eq. 19, we finally arrive at the relation

|

(21) |

where  is the variance of the adsorption constant. We note that if there is no phenotype switching

is the variance of the adsorption constant. We note that if there is no phenotype switching  can only decrease with time for

can only decrease with time for  being positive. Asymptotically, therefore,

being positive. Asymptotically, therefore,  should approach zero or correspondingly

should approach zero or correspondingly  A small but finite

A small but finite  observed in the experiment even after persistent phage pressure P(t) ∼ 1 × 108 cm−3 demands that the switching rates between bacterial subpopulations must not be zero at least within our observation time of ∼4 h. It should be emphasized that Eq. 21 is the dynamic equation for the receptors, and its relation to the sensitive bacterial population is a delicate one. This has to be the case because the interaction between a phage and its receptor is essentially a “chemical” process determined by the law of mass action, whereas the life-and-death of a bacterium is a highly nonlinear biological process. It remains an intriguing possibility that in a long time, the receptor number may reach a “chemical equilibrium” with

observed in the experiment even after persistent phage pressure P(t) ∼ 1 × 108 cm−3 demands that the switching rates between bacterial subpopulations must not be zero at least within our observation time of ∼4 h. It should be emphasized that Eq. 21 is the dynamic equation for the receptors, and its relation to the sensitive bacterial population is a delicate one. This has to be the case because the interaction between a phage and its receptor is essentially a “chemical” process determined by the law of mass action, whereas the life-and-death of a bacterium is a highly nonlinear biological process. It remains an intriguing possibility that in a long time, the receptor number may reach a “chemical equilibrium” with  (or

(or  yielding

yielding  However, the average receptor number

However, the average receptor number  in such a state is so small that the growth rate Λeff

in such a state is so small that the growth rate Λeff for the sensitive cells is positive, giving rise to exponential growth of S(t). Whether this is what happened in our late-time bacterium/phage population dynamics remains to be verified by future experiments.

for the sensitive cells is positive, giving rise to exponential growth of S(t). Whether this is what happened in our late-time bacterium/phage population dynamics remains to be verified by future experiments.

For a simple application of Eq. 21, we noted that it allows us to explain the killing data beyond the initial exponential behavior, i.e., within the first few minutes of measurements. This is because for early times  is expected to be a constant and

is expected to be a constant and  since the receptor distribution is still at the steady state. A simple integration yields

since the receptor distribution is still at the steady state. A simple integration yields  Substituting this relation into Eq. 9 and integrating over t again, we found

Substituting this relation into Eq. 9 and integrating over t again, we found

|

(22) |

In the short-time limit, this equation turns out to be the same as Eq. 16, which was derived without the switching terms. The new derivation in Eq. 22 lends support to our earlier assertion that phenotype switching is important only for the intermediate- to the long-time behavior of the bacterial population. By varying P(0) systematically, Eq. 22 can be used to find  and its standard deviation σγ (0). Equation 22 also suggests the following scaling relation:

and its standard deviation σγ (0). Equation 22 also suggests the following scaling relation: where

where  and

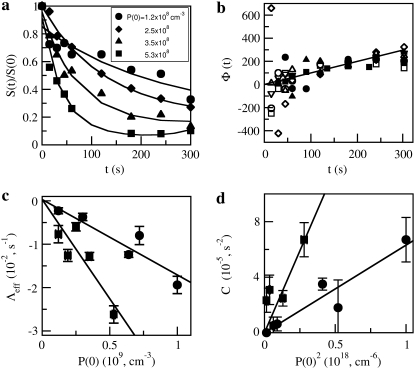

and  One thus expects that if the early-time killing curves S(t) are normalized and parameters Λeff and C are properly chosen, all the killing data should be collapsed onto a single/universal line with a slope of unity. We demonstrated this scaling procedure using the data from both strains of bacteria when P(0) was varied between 1.2 × 108 to 5.3 × 108 cm−3 for LE392, and when P(0) was varied between 1.2 × 108 to 1.0 × 109 cm−3 for Ymel. The symbols in Fig. 6 a are the original data of LE392, and the scaled curves are displayed in Fig. 6 b as open symbols, along with the measurements of Ymel bacteria (solid symbols). We found that our data collapse well only for times <∼300 s, which is consistent with the theoretical prediction since for t ≫ Λeff/C, Eq. 22 is no longer valid. The above scaling procedure also allows us to verify the linear and quadratic relationships between Λeff and C with P(0), which are plotted in Fig. 6, c and d. Based on this analysis, we found that the average adsorption coefficient and its variance are given by

One thus expects that if the early-time killing curves S(t) are normalized and parameters Λeff and C are properly chosen, all the killing data should be collapsed onto a single/universal line with a slope of unity. We demonstrated this scaling procedure using the data from both strains of bacteria when P(0) was varied between 1.2 × 108 to 5.3 × 108 cm−3 for LE392, and when P(0) was varied between 1.2 × 108 to 1.0 × 109 cm−3 for Ymel. The symbols in Fig. 6 a are the original data of LE392, and the scaled curves are displayed in Fig. 6 b as open symbols, along with the measurements of Ymel bacteria (solid symbols). We found that our data collapse well only for times <∼300 s, which is consistent with the theoretical prediction since for t ≫ Λeff/C, Eq. 22 is no longer valid. The above scaling procedure also allows us to verify the linear and quadratic relationships between Λeff and C with P(0), which are plotted in Fig. 6, c and d. Based on this analysis, we found that the average adsorption coefficient and its variance are given by  cm3/s and

cm3/s and  cm3/s for Ymel, and

cm3/s for Ymel, and  cm3/s and

cm3/s and  cm3/s for LE392. Using Berg and Purcell's prediction in Eq. 1,

cm3/s for LE392. Using Berg and Purcell's prediction in Eq. 1,  and

and  can be converted to

can be converted to  and σn. We found that

and σn. We found that  and σn extracted in this fashion are in reasonably good agreement with the flow cytometry measurements as delineated in Table 1.

and σn extracted in this fashion are in reasonably good agreement with the flow cytometry measurements as delineated in Table 1.

FIGURE 6.

Short-time (<5 min) killing curves for Ymel and LE392. (a) Examples of short-time killing curves for LE392 with initial phage concentrations of P(0) = 1.2 × 108 cm−3 (circles); 2.5 × 108 cm−3 (diamonds); 3.5 × 108 cm−3 (triangles) ; and 5.3 × 108 cm−3 (squares). Lines are guides to the eye. (b) Nine different killing curves, such as the ones displayed in panel a, can be collapsed onto a straight line characterized by the equation  Here data from both LE392 (open symbols) and Ymel (solid symbols) bacteria were used. (c and d) The circles and the squares are, respectively, for Ymel and induced LE392 bacteria. The parameters Λeff and C are defined in the equation for Φ(s), shown in this legend. The slopes in panels c and d allow

Here data from both LE392 (open symbols) and Ymel (solid symbols) bacteria were used. (c and d) The circles and the squares are, respectively, for Ymel and induced LE392 bacteria. The parameters Λeff and C are defined in the equation for Φ(s), shown in this legend. The slopes in panels c and d allow  and σγ(0) to be calculated (see main text), and their values are listed in Table 1.

and σγ(0) to be calculated (see main text), and their values are listed in Table 1.

CONCLUSION

We have presented a theoretical model taking into account known interactions between bacterium and phage. A distinguishable feature of our model is the division of bacteria into subpopulations depending on their phage receptor numbers. For a narrow receptor distribution, this heterogeneous model can be reduced to the standard homogeneous one that is typically used in the literature. It is also shown that while the homogeneous model lacks the plasticity for the bacterial population to coexist with a phage population, which typically leads S(t) to extinction in long times, the heterogeneous model is much more robust and S(t) does not become extinct unless a persistent, high phage pressure is present. This is consistent with our experimental observation in Part I where mutants are present in significant numbers only when a large pressure of P(0) > 1010 cm−3 is applied.

The Berg-Purcell's theoretical result for the phage adsorption rate allows the cell states to be enumerated, and the statistical properties of birth/death rates to be calculated for the heterogeneous bacterial population. It is surprising that statistical fluctuations in the receptor number alone appears to account for the main features of bacterium/phage population dynamics, including the coexistence of the two species over a broad range of phage pressures. The improved fitness in the heterogeneous population results from the fact that in the presence of phage, the high-n cells are preferentially infected. In the case when the MOI is much less than the average number of receptors per bacterium  the high-n cells also effectively shield low-n cells from phage attack, allowing the latter to grow despite the phage pressure. At the population level, the improved fitness is manifested by a time-dependent adsorption rate

the high-n cells also effectively shield low-n cells from phage attack, allowing the latter to grow despite the phage pressure. At the population level, the improved fitness is manifested by a time-dependent adsorption rate  that decreases with time until the effective growth rate

that decreases with time until the effective growth rate  becomes positive at a long time. Interestingly, our experiment shows that the transition from Λeff < 0 to Λeff > 0 takes a very long time (4–5 h), and in the intervening period, the system appears to be locked in a quasi-steady state with Λeff = 0. This behavior cannot be accounted for by the receptor-number heterogeneity alone, and it appears that phenotype switching is essential for the observed quasi-steady state. In our opinion, the time-dependent

becomes positive at a long time. Interestingly, our experiment shows that the transition from Λeff < 0 to Λeff > 0 takes a very long time (4–5 h), and in the intervening period, the system appears to be locked in a quasi-steady state with Λeff = 0. This behavior cannot be accounted for by the receptor-number heterogeneity alone, and it appears that phenotype switching is essential for the observed quasi-steady state. In our opinion, the time-dependent  in the presence of a phage pressure is an important observation of this experiment. It invalidates an important assumption in early bacterium/phage population models: which assume

in the presence of a phage pressure is an important observation of this experiment. It invalidates an important assumption in early bacterium/phage population models: which assume  to be a constant having the same value

to be a constant having the same value  determined from a unstressed population. The experiment herein demonstrates that

determined from a unstressed population. The experiment herein demonstrates that  can change by orders of magnitude under a phage stress.

can change by orders of magnitude under a phage stress.

While the full model presented by Eqs. 5–7 is complex, it admits solutions when certain approximations are made, such as when 1), the phage pressure is so high that it can be considered as constant; 2), no phenotype switching is present; and 3), the short- and perhaps the intermediate-time limits are considered. We found that for slow switching rates, the approximations 2 and 3 are equivalent, yielding similar solutions for S(t) as delineated by Eqs. 14 and 22. These approximations are admittedly rather crude, but they can reproduce qualitative behaviors that are consistent with the observations, suggesting that population heterogeneity is an essential feature of bacterium/phage population dynamics. In the short-time limit, however, these equations can yield quantitative results as demonstrated by their predictive power for  and σn as delineated in Fig. 6. Perhaps the most significant result of the theoretical analyses is the prediction:

and σn as delineated in Fig. 6. Perhaps the most significant result of the theoretical analyses is the prediction:  The first term in this equation causes the average adsorption rate to decrease with time while the second term causes it to increase. Since our measured

The first term in this equation causes the average adsorption rate to decrease with time while the second term causes it to increase. Since our measured  never approaches zero after several hours of phage stress for a variety of P(0), it provides evidence that phenotype switching must take place or

never approaches zero after several hours of phage stress for a variety of P(0), it provides evidence that phenotype switching must take place or  must not be zero for our bacterium/phage system.

must not be zero for our bacterium/phage system.

Since the comparison between theory and experiment is only qualitative at the present level of analysis, particularly for the intermediate- and long-times, there is ample room for future improvements. It appears that the most important missing piece is the biological mechanism for phenotype switching. This requires both experimental and theoretical efforts to sort out. Experimentally, a better understanding of LamB protein dynamics, i.e., the synthesis, folding, receptor assembly, and partitioning during cell division, is urgently needed. Theoretically, the presentation of the population dynamic equations by a set of ordinary differential equations is highly inconvenient. It would be useful to develop a coarse-grained model in the spirit of balanced-population models, which have been successfully used for describing stochastic bacterial cell division (23). However, how to rationally couple the random protein dynamics of interest, such as our LamB, with the cell growth/division parameter remains to be investigated. New insights may also be gained by investigating the regulation of the maltose regulon, which appears to operate differently from the more commonly studied lactose or arabinose regulatory systems (24,25). It has been recognized by early genetic studies that MalT, which is a positive regulator of the maltose regulon, is not self-regulated and its expression is limited both at the transcription and translation levels (26,27). This regulation scheme is peculiar because it suggests that the regulon is intrinsically noisy. While it makes sense in most circumstances for a gene circuit to minimize stochastic fluctuations, noisy gene regulation can in other circumstances be advantageous particularly when organisms are subject to fluctuating environmental stresses (28). In the present case of maltose regulon, the stochasticity would allow the cell population to prosper in very low concentrations of maltose while still able to face the challenge of λ-phage. Thus, it remains an intriguing possibility that evolution of maltose regulon is strongly influenced by the selection pressures of bacterial viruses, such as λ, K10, and TPI, which exploit the maltose receptor LamB (29). Theoretically, it will be very useful to model the maltose regulon to see if the broad LamB distribution can result from its peculiar regulation mechanism.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate many useful discussions with Chuck Yeung to clarify a number of ideas in the model.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant No. PHY-0646573. E.C-M.. acknowledges partial support by the National Science Foundation during this project as a GK-12 Fellow under grant No. 0338135 (GK-12: The Pittsburgh Partnership for Energizing Science in Urban Schools).

Editor: Arup Chakraborty.

References

- 1.Elowitz, M. B., A. J. Levine, E. D. Siggia, and P. S. Swain. 2002. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 297:1183–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raser, J. M., and E. O'Shea. 2005. Noise in gene expression: origins, consequences and control. Science. 309:2010–2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halme, A., S. Bumgarner, C. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 2004. Genetic and epigenetic regulation of the FLO gene family generates cell-surface variation in yeast. Cell. 116:405–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pedraza, J. M., and A. van Oudenaarden. 2005. Noise propagation in gene networks. Science. 307:1965–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balaban, N. Q., J. Merrin, R. Chait, L. Kowalik, and S. Leibler. 2004. Bacterial persistence as a phenotypic switch. Science. 305:1622–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kussell, E., R. Kishnoy, N. Q. Balaban, and S. Leibler. 2005. Bacterial persistence: a model of survival in changing environment. Genetics. 169:1807–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thattai, M., and A. van Oudenaarden. 2004. Stochastic gene expression in fluctuating environments. Genetics. 167:523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai, L., N. Friedman, and X. S. Xie. 2006. Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature. 440:358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryter, A., H. Shuman, and M. Schwartz. 1975. Integration of the receptor for bacteriophage-λ in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli: coupling with cell division. J. Bacteriol. 122:295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin, B. R., F. M. Stewart, and L. Chao. 1977. Resource-limited growth, competition and predation: a model and experimental studies with bacteria and bacteriophage. Am. Nat. 111:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao, L., B. R. Levin, and F. M. Steward. 1977. A complex community in a simple habitat: an experimental study with bacteria and phage. Ecology. 58:369–378. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenski, R. E., and B. R. Levin. 1985. Constraints on the coevolution of bacteria and virulent phage: a model, some experiments, and predictions for natural communities. Am. Nat. 125:585–602. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moldovan, R., E. Chapman-McQuiston, and X. L. Wu. 2007. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys. J. 93:303–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovitch, A. 2003. Bacterial debris—an ecological mechanism for coexistence of bacteria and their viruses. J. Theor. Biol. 224:377–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg, H. C., and E. M. Purcell. 1977. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 20:193–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz, M. 1976. The adsorption of coliphage-λ to its host: effect of variation in the surface density of receptor and in phage-receptor affinity. J. Mol. Biol. 103:521–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zwanzig, R. 1990. Diffusion-controlled ligand binding to spheres partially covered by receptors: an effective medium treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:5856–5857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wangersky, P. J. 1978. Lotka-Volterra population models. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 9:189–218. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szmelcman, S., and M. Hofnung. 1975. Maltose transport in Escherichia coli K-12: involvement of the bacteriophage λ-receptor. J. Bacteriol. 124:112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Press, W. H., S. A. Teukolsky, W. T. Vetterling, and B. P. Flannery. 1988. Numerical Recipes in C: The Art of Scientific Computing. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- 21.Banerjee, B., S. Balasubramanian, G. Ananthakrishna, T. V. Ramakrishnan, and G. V. Shivashankar. 2004. Tracking operator state fluctuations in gene expression in single cells. Biophys. J. 86:3052–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishna, S., B. Banerjee, T. V. Ramakrishnan, and G. V. Shivashankar. 2005. Stochastic simulations of the origins and implications of long-tailed distributions in gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:4771–4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramkrishna, D. 2000. Population Balances: Theory and Applications to Particulate Systems in Engineering. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 24.Novick, A., and M. Weiner. 1957. Enzyme induction as an all-or-none phenomenon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 43:553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegele, D., and J. C. Hu. 1997. Gene expression from plasmids containing the araBAD promoter at subsaturating inducer concentration represents mixed populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:8168–8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapon, C. 1982. Expression of MalT, the regulator gene of the maltose regulon in Escherichia coli, is limited both at transcription and translation. EMBO J. 1:369–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz, M. 1987. The maltose regulon. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, Cellular and Molecular Biology. F. C. Neidhardt, Editor. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 28.Bar-Even, A., J. Paulsson, N. Maheshri, M. Carmi, E. O'Shea, Y. Pilpel, and N. Barkai. 2006. Noise in protein expression scales with natural protein abundance. Nat. Genet. 38:636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz, M. 1980. Interaction of phages with their receptor proteins. In Virus Receptors. Receptors and Recognition, B Series. L. L. Randall and L. Philipson, Editors. Chapman and Hall, London.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.