Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the associations between UGT1A1*28 genotype and (1) response rates, (2) febrile neutropenia and (3) dose intensity in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with irinotecan. UGT1A1*28 genotype was determined in 218 patients receiving irinotecan (either first-line therapy with capecitabine or second-line as monotherapy) for metastatic colorectal cancer. TA7 homozygotes receiving irinotecan combination therapy had a higher incidence of febrile neutropenia (18.2%) compared to the other genotypes (TA6/TA6 : 1.5%; TA6/TA7 : 6.5%, P=0.031). TA7 heterozygotes receiving irinotecan monotherapy also suffered more febrile neutropenia (19.4%) compared to TA6/TA6 genotype (2.2%; P=0.015). Response rates among genotypes were not different for both regimens: combination regimen, P=0.537; single-agent, P=0.595. TA7 homozygotes did not receive a lower median irinotecan dose, number of cycles (P-values ⩾0.25) or more frequent dose reductions compared to the other genotypes (P-values for trend; combination therapy: 0.62 and single-agent: 0.45). Reductions were mainly (>80%) owing to grade ⩾3 diarrhoea, not (febrile) neutropenia. TA7/TA7 patients have a higher incidence of febrile neutropenia upon irinotecan treatment, but were able to receive similar dose and number of cycles compared to other genotypes. Response rates were not significantly different.

Keywords: colorectal, dose, irinotecan, response, toxicity, UGT1A1*28

Colorectal carcinoma is one of the most common cancers in the western world and the second largest cause of cancer-related death (Boyle and Ferlay, 2005). Approximately 50% of patients present with distant metastases either at diagnosis or during follow-up for which curative treatment is no longer possible. In the palliative setting, the median overall survival has increased from approximately 8 months without treatment to approximately 21 months using 5-fluorouracil (or its oral prodrug capecitabine), irinotecan (IRI), oxaliplatin and targeted agents (Punt, 2004). One of the most studied metabolic enzymes of the IRI pathway is uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase, UGT1A1. It converts the active metabolite of IRI, SN38, to its inactive glucuronide (Iyer et al, 1998) and is expressed in the liver, the relative amount being dependent on the number of TA-repeats in the promoter of the gene (wild-type, TA6 or UGT1A1*28, TA7). The TA7 allele results in lower UGT1A1 expression and decreased SN-38 glucuronidation (Ando et al, 1998, 2002; Iyer et al, 1999; Paoluzzi et al, 2004). TA7/TA7 patients, therefore, have a higher SN38 exposure and hence an increased chance to experience toxic side effects (Iyer et al, 2002; Innocenti et al, 2004; Marcuello et al, 2004). One can also hypothesise that TA6 homozygotes may tolerate a higher IRI dosage, possibly increasing treatment benefit. Indeed, several reports show that IRI dose can be increased in a subset of patients (Merrouche et al, 1997; Ducreux et al, 1999; Ychou et al, 2002), and there is indirect evidence that the efficacy of IRI seems dose-dependent (Abigerges et al, 1995). Recently, the FDA has approved the updated Camptosar® (IRI) product labelling that recommends a reduced starting dose for TA7/TA7 patients to prevent haematological toxicity.

Our primary aim was to investigate the efficacy by genotype. Secondly, we investigated the association between UGT1A1*28 and febrile neutropenia as this concerns a clinically relevant complication of treatment with IRI. It leads to hospital admissions and may pose a serious medical problem, especially when occurring with diarrhoea. Thirdly, we studied the number of IRI cycles and dosage by genotype.

Patients and methods

Subjects

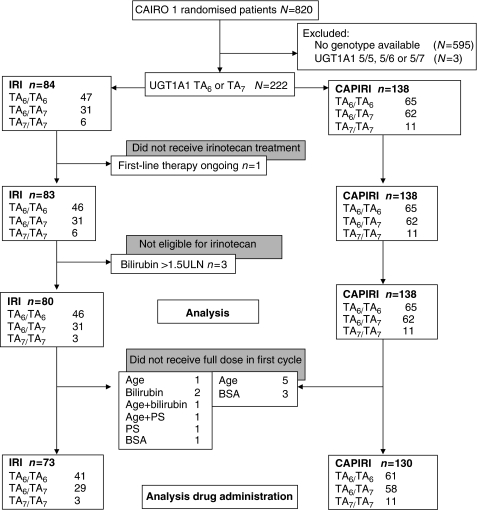

Blood samples were obtained from patients enrolled in a multicentre phase III trial of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG), referred to as the CAIRO study. Eligibility criteria, interim safety results (Koopman et al, 2006) and survival data (Koopman et al, 2007) have been published. Briefly, patients were allocated to regimen A or B. Regimen A consisted of first-line capecitabine (1250 mg m−2 day−1 b.i.d. on days 1–14, every 3 weeks), second-line IRI (350 mg m−2 day−1 on day 1, every 3 weeks) and third-line capecitabine plus oxaliplatin. Regimen B consisted of first-line capecitabine (1000 mg m−2 day−1 b.i.d. on days 1–14, every 3 weeks) plus IRI (250 mg −2 day−1 on day 1, every 3 weeks: capecitabine plus IRI (CAPIRI), followed by second-line capecitabine plus oxaliplatin. Initial IRI dose of 80% in cycle 1 was recommended when: age >70 years, WHO performance status 2 and/or serum bilirubin 1.0–1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN). If well tolerated, the dose was increased to 100% in subsequent cycles. Irinotecan dose was reduced with 25% relative to the previous cycle in case of any grade 3–4 toxicity with the exception of nausea/vomiting when adequate prophylaxis was still available. If these toxicities recurred despite dose reduction, the dose was reduced to 50% and upon next recurrence the treatment was discontinued. Diarrhoea was treated with loperamide (2 mg every 2 h, for a minimum of 12 h and a maximum treatment duration of 48 h). Prophylactic use of haematological growth factors and loperamide was not permitted. Inclusion took place from January 2003 to December 2004, and EDTA blood samples for genotyping were collected from October 2003 to March 2005 after a protocol amendment. The objective was to perform genetic association studies regarding antitumour response and toxicity. The study protocol and the amendment were approved by the local ethical committees. Patients were asked to participate in this side-study at inclusion, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the genetic association study before blood collection. DNA was obtained from 268 patients (regimen B: 141 subjects; regimen A: 127). Of the patients in regimen A, 83 continued to receive second-line therapy with IRI (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients in current analysis. Abbreviations: BSA=body surface area; CAPIRI=irinotecan first-line combination therapy (250 mg m−2 every 3 weeks, with capecitabine); IRI=irinotecan (350 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) second-line single-agent therapy; PS=performance status; ULN=upper limit of normal.

Clinical evaluation

Tumour evaluation was performed by means of CT or MRI every three cycles according to RECIST (Therasse et al, 2000) criteria and results were blinded with respect to genotype data. Toxicity was graded according to NCI common toxicity criteria version 2.0 (Anonymous, 1998). We used febrile neutropenia and worst grade of diarrhoea experienced during treatment with IRI. Overall toxicity was defined as any grade 3 or 4 toxicity that occurred during treatment. Neutrophil counts were not routinely performed, but all patients were instructed to contact the hospital in case of fever. If so, neutrophil counts were determined. Irinotecan dose was calculated as the sum of all IRI doses (mg) and as the sum of all doses, divided by body surface area (BSA), mg m−2. Body surface area was calculated with the Mosteller formula, based on height and weight (at current or previous cycle). The relative dose intensity, RDI, is the dose in mg m−2 received divided by the protocol dose and expressed in percentage. The overall RDI is the sum of RDIs divided by the number of cycles received. A dose reduction is defined as a reduction of at least 10% compared to the previous dose. Dose reductions were analysed in patients receiving at least two doses of IRI. DNA isolation and genotyping methods are published online in the Supplementary Data file.

Statistics

All eligible patients with UGT1A1 TA6/TA6, TA6/TA7 and TA7/TA7 genotypes who received IRI were considered for toxicity analysis. Patients were included in response analysis, if they were evaluable for response. In dosage analysis, we studied only those patients who received a full starting dose. Patients who received only one cycle were considered as having no recorded dose reduction.

Kruskal–Wallis, χ2 and (exact) Cochrane–Armitage trend tests were used to investigate the association of genotypes and patient characteristics. Logistic regression, stratified by regimen, was performed to investigate the association of UGT1A1 with the probability of febrile neutropenia. We performed bivariate analyses of UGT1A1*28 and a separate covariate (gender, age, site of primary tumour, prior chemotherapy, thymydilate synthase (TS) 6 bp deletion (Mandola et al, 2004), TS number of active repeats (Pullarkat et al, 2001) (as defined by Mandola (Mandola et al, 2003)), P-glycoproteins ABCB1 C1236T and ABCG2 C421A (Smith et al, 2006)) to explore a possible association of these variables with an adverse event.

All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1.3; in all analyses, P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, and therefore, this study needs to be regarded as exploratory only.

A retrospective power analysis reveals that with the given sample sizes and a genotype distribution of 45, 45 and 10% (TA6/TA6, TA6/TA7 and TA7/TA7, respectively), a Cochrane–Armitage trend test could have detected realistic differences in response rates (regimen A response rates: 6, 16 and 33% (TA6/TA6; TA6/TA7 and TA7/TA7, respectively) and regimen B: 34, 50 and 57%) with P=0.05 at β=0.8.

Results

UGT1A1 genotype frequencies were: 50.5% (n=112) TA6 homozygotes, 41.9% (n=93) heterozygotes and 7.7% (n=17) TA7 homozygotes. Other genotypes found were TA5/TA5 (n=1), TA5/TA6 (1) and TA5/TA7 (1); these uncommon genotypes were excluded from the analysis. Patients were predominantly Caucasian. Frequencies were in Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium and in accordance with the published results in Caucasians (Innocenti et al, 2004; Paoluzzi et al, 2004; Carlini et al, 2005; Toffoli et al, 2006). Of patients receiving first-line CAPIRI, 127 patients were evaluable for response and 138 for toxicity, and of the patients receiving second-line IRI, these were 77 and 80, respectively. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by regimen.

|

IRI

|

CAPIRI

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | |||||

| TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | |||

| UGT1A1 | N=46 | N=31 | N=3 | N=80 | P-value | N=65 | N=62 | N=11 | N=138 | P-value |

| Localisation of primary tumour (%) | ||||||||||

| Colon | 25 (54) | 16 (52) | 2 (67) | 43 (54) | P=0.969# | 33 (51) | 36 (58) | 7 (64) | 76 (55) | P=0.821# |

| Rectosigmoid | 5 (11) | 3 (10) | 8 (10) | 5 (8%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (9) | 9 (7) | |||

| Rectal | 16 (35) | 12 (39) | 1 (33) | 29 (36) | 27 (42%) | 23 (37%) | 3 (27) | 53 (38) | ||

| Gender (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 25 (54) | 23 (74) | 3 (100) | 51 (64) | P=0.085# | 41 (63%) | 41 (66%) | 4 (36) | 86 (62) | P=0.169# |

| Female | 21 (46) | 8 (26) | 29 (36) | 24 (37%) | 21 (34%) | 7 (64) | 52 (38) | |||

| Age at randomisation | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 60.5 (46.0–78.0) | 61.0 (36.0–78.0) | 57.0 (48.0–75.0) | 61.0 (36.0–78.0) | P=0.8744$ | 62.0 (44.0–81.0) | 63.0 (37.0–78.0) | 60.0 (46.0–74.0) | 62.0 (37.0–81.0) | P=0.6661$ |

| Prior adjuvant treatment primary tumour at randomisation (%) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 5 (11) | 4 (13) | 1 (33) | 10 (13) | P=0.520# | 7 (11) | 7 (11) | 3 (27) | 17 (12) | P=0.289# |

| No | 41 (89) | 27 (87) | 2 (67) | 70 (88) | ||||||

| Predominant localisation of metastases at randomisation (%) | ||||||||||

| Liver | 32 (70) | 23 (74) | 1 (33) | 56 (70) | P=0.495# | 40 (62) | 48 (77) | 8 (73) | 96 (70) | P=0.147# |

| Extrahepatic | 11 (24) | 7 (23) | 2 (67) | 20 (25) | 25 (38) | 14 (23) | 3 (27) | 42 (30) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (5) | |||||||

| Performance status at start IRI (%) | ||||||||||

| 0 | 23 (50) | 18 (58) | 2 (67) | 43 (54) | P=0.857# | 39 (60) | 38 (61) | 5 (45) | 82 (59) | P=0.392# |

| 1 | 21 (46) | 12 (39) | 1 (33) | 34 (43) | 21 (32) | 22 (35) | 4 (36) | 47 (34) | ||

| 2 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 4 (6%) | 2 (3) | 2 (18) | 8 (6) | ||||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (2%) | 1 (<1) | |||||

| Bilirubin level at start IRI | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 10.0 (4.0–22.0) | 13.0 (7.0–31.0) | 27.0 (27.0–27.0) | 10.5 (4.0–31.0) | P=0.0009$ | 8.0 (3.0–67.0) | 10.0 (1.0–19.0) | 13.9 (7.0–24.0) | 9.0 (1.0–67.0) | P=0.0106$ |

| LDH level at start IRI | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 443.0 (146.0–2316.0) | 436.0 (165.0–3493.0) | 466.0 (310.0–604.0) | 443.0 (146.0–3493.0) | P=0.9903$ | 410.0 (151.0–2243.0) | 360.0 (119.0–3320.0) | 336.5 (250.0–1213.0) | 377.0 (119.0–3320.0) | P=0.1778$ |

| ABCB1 (%) | ||||||||||

| TT | 7 (15) | 5 (16) | 2 (67) | 14 (18) | P=0.215# | 7 (11) | 11 (18) | 3 (27) | 21 (15) | P=0.282# |

| TC | 19 (41) | 14 (45) | 1 (33) | 34 (43) | 36 (55) | 34 (55) | 3 (27) | 73 (53) | ||

| CC | 20 (43) | 12 (39) | 32 (40) | 22 (34) | 16 (26) | 5 (45) | 43 (31) | |||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (<1) | ||||||||

| ABCG2 (%) | ||||||||||

| TT | 36 (78) | 18 (58) | 3 (100) | 57 (71) | P=0.174# | 52 (80) | 43 (69) | 8 (73) | 103 (75) | P=0.458# |

| TC | 9 (20) | 12 (39) | 21 (26) | 10 (15) | 16 (26) | 3 (27) | 29 (21) | |||

| CC | 1 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 4 (3) | |||||

| Missing | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 2 (1) | ||||||

| TS number of active repeats (%) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 3 (4) | P=0.861# | ||||||

| 2 | 26 (57) | 19 (61) | 1 (33) | 46 (58) | 30 (46) | 33 (53) | 5 (45) | 68 (49) | P=0.306# | |

| 3 | 14 (30) | 6 (19) | 1 (33) | 21 (26) | 27 (42) | 18 (29) | 5 (45) | 50 (36) | ||

| 4 | 2 (4) | 2 (6) | 4 (5) | 3 (5) | 7 (11) | 10 (7) | ||||

| Missing | 3 (7) | 2 (6) | 1 (33) | 6 (8) | 5 (8) | 4 (6) | 1 (9) | 10 (7) | ||

| TS del (%) | ||||||||||

| del/del | 5 (11) | 1 (3) | 6 (8) | P=0.488# | 3 (5%) | 10 (16) | 13 (9) | P=0.121# | ||

| +6/del | 12 (26) | 8 (26) | 2 (67) | 22 (28) | 28 (43) | 27 (44) | 4 (36) | 59 (43) | ||

| +6/+6 | 26 (57) | 18 (58) | 1 (33) | 45 (56) | 30 (46) | 20 (32) | 5 (45) | 55 (40) | ||

| Missing | 3 (7) | 4 (13) | 7 (9) | 4 (6) | 5 (8) | 2 (18) | 11 (8) | |||

CAPIRI= irinotecan first-line combination therapy (250 mg m−2 every 3 weeks, with capecitabine); IRI: irinotecan (350 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) second-line single-agent therapy; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase; TS=thymydilate synthase.

#χ2.

$Kruskal–Wallis.

Tumour response

Overall objective tumour response (complete (CR) and partial (PR) responses) in patients treated with CAPIRI was 47.2% (CR+PR) and 14.3% for IRI. Patients with TA6/TA6 receiving CAPIRI achieved 49.2% response, compared to 43.1% of TA6/TA7 and 62.5% of TA7/TA7 patients (P=0.537; Table 2). Response rates for IRI were: 15.9% TA6/TA6, and 13.3% TA6/TA7. Only stable diseases were observed in TA7/TA7 patients receiving IRI.

Table 2. Response, toxicity and dose during IRI treatment.

|

IRI

|

CAPIRI

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | |||||

| UGT1A1 | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | ||

| Evaluable for response | N=44 | N=30 | N=3 | N=77 | P-value | N=61 | N=58 | N=8 | N=127 | P-value |

| Best overall response (%) | ||||||||||

| CR | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 1 (13) | 5 (4) | ||||||

| PR | 7 (16) | 4 (13) | 11 (14) | 29 (48) | 22 (38) | 4 (50) | 55 (43) | |||

| SD | 27 (61) | 16 (53) | 3 (100) | 46 (60) | 27 (44) | 30 (52) | 2 (25) | 59 (46) | ||

| PD | 10 (23) | 10 (33) | 20 (26) | 4 (7) | 3 (5) | 1 (13) | 8 (6) | |||

| Response rate, %, (95% exact CI) | 15.9 (6.6:30.1) | 13.3 (3.8:30.7) | 0.0 (0%:70.8) | 14.3 (7.4:24.1) | 0.595L | 49.2 (36.1:62.3) | 43.1 (30.2:56.8) | 62.5 (24.5:91.5) | 47.2 (38.3:56.3) | 0.537L |

| Disease control, %, rate (95% exact CI) | 77.3 (62.2:88.5) | 66.7 (47.2:82.7) | 100 (29.2:100) | 74.0 (62.8:83.4) | 0.240L | 93.4 (84.1:98.2) | 94.8 (85.6:98.9) | 87.5 (47.3:99.7) | 93.7 (88.0:97.2) | 0.759L |

| TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | |||||

| UGT1A1 | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | ||

| Evaluable for toxicity (grade 3–4) | N=46 | N=31 | N=3 | N=80 | P-value | N=65 | N=62 | N=11 | N=138 | P-value |

| Overall (%) | ||||||||||

| All cycles | 20 (43.5) | 12 (38.7) | 3 (100) | 35 (43.8) | Etrend 0.56 | 33 (50.8) | 33 (53.2) | 8 (72.7) | 74 (53.6) | Etrend 0.35 |

| Cycle 1 | 3 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.8) | FE 0.430 | 3 (4.6) | 6 (9.7) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (7.2) | Etrend 0.44 |

| Febrile neutropenia (%) | ||||||||||

| All cycles | 1 (2.2) | 6 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.8) | FE 0.015 | 1 (1.5) | 4 (6.5) | 2 (18.2) | 7 (5.1) | Etrend 0.031 |

| Cycle 1 | 1 (2.2) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.8) | FE 0.561 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (2.2) | Etrend 0.008 |

| Diarrhea | ||||||||||

| All cycles | 7 (15.2) | 7 (22.6) | 2 (66.7) | 16 (20.0) | Etrend 0.090 | 14 (21.5) | 14 (22.6) | 4 (36.4) | 32 (23.2) | Etrend 0.43 |

| Cycle 1 | 3 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (8.8) | FE 0.430 | 3 (4.6) | 6 (9.7) | 1 (9.1) | 10 (7.2) | Etrend 0.44 |

| TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | TA6 | TA6 | TA7 | |||||

| UGT1A1 | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | TA6 | TA7 | TA7 | Total | ||

| Evaluable for dose analysis | N=41 | N=29 | N=3 | N=73 | P-value | N=61 | N=58 | N=11 | N=130 | P-value |

| Number of cycles | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 6 (3–17) | 6 (1–15) | 8 (4–8) | 6 (1–17) | 0.33$ | 9 (1–30) | 9 (1–32) | 9 (1–30) | 9 (1–32) | 0.66$ |

| Total dose ( g ) | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 4.4 (1.7–11.2) | 3.6 (0.7–10.8) | 4.0 (2.6–4.9) | 4.2 (0.7–11.2) | 0.39$ | 3.8 (0.4–10.7) | 3.7 (0.4–14.7) | 3.0 (0.5–14.7) | 3.7 (0.4–14.7) | 0.44$ |

| Total dose ( g m −2 ) | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 2.1 (1.0–6.0) | 2.0 (0.3–5.3) | 2.3 (1.4–2.4) | 2.1 (0.3–6.0) | 0.25$ | 2.1 (0.3–6.2) | 2.0 (0.2–8.0) | 1.9 (0.2–7.6) | 2.0 (0.2–8.0) | 0.51$ |

| Dose (mg m −2 ) per cycle | ||||||||||

| Median (range) | 347 (266–390) | 336 (272–364) | 302 (284–355) | 341 (266–390) | 0.45$ | 242 (84–257) | 242 (190–277) | 242 (156–253) | 242 (84–277) | 0.83$ |

| Reduction of IRI after cycle 1 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 15 | 0.45E | 12 | 13 | 3 | 28 | 0.62E |

| Cycle of first reduction (%) | ||||||||||

| Cycle 2–3 | 4 (50) | 4 (80) | 1 (50) | 9 (60) | 0.544L | 5 (42) | 9 (69) | 1 (33) | 15 (54) | 0.444L |

| Cycle 4–6 | 1 (13) | 1 (20) | 2 (13) | NS | 4 (33) | 2 (15) | 1 (33) | 7 (25) | NS | |

| Cycle 7–9 | 1 (13) | 1 (50) | 2 (13) | NS | 2 (17) | 1 (8) | 1 (33) | 4 (14) | NS | |

| Cycle ⩾10 | 2 (25) | 2 (13) | NS | 1 (8) | 1 (8) | 2 (7) | NS | |||

CAPIRI=irinotecan first-line combination therapy (250 mg m−2 every 3 weeks, with capecitabine); CI=confidence interval; CR=complete response; E=exact; Etrend=exact-values for trend; FE=Fisher's exact; IRI=irinotecan (350 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) second-line single-agent therapy; L=logistic regression; NS=statistically non-significant difference; PD=progressive disease; PR=partial response; SD=stable disease.

Response is defined as CR or PR, disease control as CR, PR or SD.

P-values are calculated by L, Etrend, E, FE or Kruskal–Wallis.

$Kruskal–Wallis.

Toxicity

Six of 138 patients receiving CAPIRI (5.1%) and in 7 of 80 patients receiving IRI (8.8%) experienced neutropenic fever. The incidence of febrile neutropenia in the CAPIRI regimen was 18.2% in TA7/TA7 compared to 1.5% in TA6/TA6 and 6.5% in TA6/TA7 patients (P=0.031, Table 2). TA7 homozygotes receiving CAPIRI had increased risk of 14.2 (OR 95% CI: 1.17–173) to develop neutropenic fever compared to TA6 homozygotes. All TA7/TA7 patients developing febrile neutropenia experienced this adverse effect in the first IRI cycle. Thirty-two of 138 patients receiving CAPIRI (23.2%) and 16 of 80 patients receiving IRI (20.0%) experienced severe diarrhoea (grade ⩾3). Of the TA7 homozygotes receiving CAPIRI, 36.4% experienced severe diarrhoea, as opposed to 21.5% of TA6 homozygotes and 22.6% of heterozygotes (P-value for trend: 0.43).

The incidence of febrile neutropenia was also higher in TA7 heterozygotes receiving IRI (P=0.015) relative to TA6/TA6 patients. Of the TA6/TA6 patients treated with this regimen, 2.2% experienced febrile neutropenia compared to 19.4% of TA6/TA7 patients (none of the four TA7/TA7 patients experienced this side effect). Of the TA7 homozygotes in this regimen, 66.7% developed grade 3 or 4 diarrhoea compared to 15.2% of TA6/TA6 and 22.6% of TA6/TA7 (P=0.09). The majority of severe diarrhoea episodes were not seen in cycle 1 but in subsequent cycles.

Irinotecan dosing

As described above, we excluded from IRI dose analysis those patients who received a reduced starting dose of IRI (Figure 1). For this reason, seven patients randomised to CAPIRI and eight patients randomised to IRI were excluded. Characteristics of the patients (n=203) included in dosage analysis are shown in the electronic Supplementary Data file.

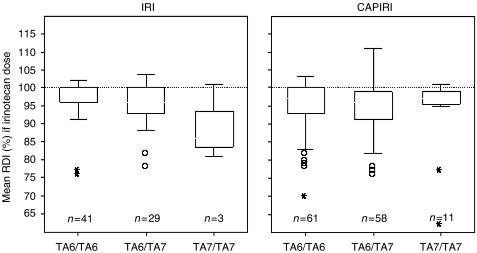

For CAPIRI, TA7 homozygotes did not receive a lower mean IRI dose (RDI, P=0.83) or median number of cycles (P=0.66; Table 2 and Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the total dose of IRI received over all cycles: 1.9 g m−2 (TA7/TA7) compared to 2.1 g m−2 and 2.0 g m−2 in TA6/TA6 and TA6/TA7 patients, respectively (P=0.51). Likewise, there were no statistically significant differences in median IRI dosage or number of cycles between UGT1A1 genotypes treated with IRI (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean RDI (%) of irinotecan dose per regimen. Boxplots of mean irinotecan dose intensity per cycle. In patients receiving either irinotecan alone or in combination with capecitabine, no statistally significant differences in relative dose intensity were observed (P=0.45 and P=0.83, respectively). Abbreviations: CAPIRI=irinotecan first-line combination therapy (250 mg m−2 every 3 weeks, with capecitabine); IRI=irinotecan (350 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) second-line single-agent therapy; 0 depicts a patient with an extreme dosage of irinotecan per cycle; *depicts an outlier.

Individual dose adjustments in cycle 2 and subsequent cycles were made to manage serious side effects. The majority of adjustments occurred in cycles 2 and 3 for both CAPIRI and IRI. In CAPIRI, 27% of patients with the TA7/TA7 genotype received a dose reduction, compared to 18% of TA6/TA6 and 21% of TA6/TA7 (P-value for trend: 0.62). Reductions in cycles 2 and 3 were mainly owing to non-haematological toxicity (n=13; 87%), which predominantly consisted of grade ⩾3 diarrhoea. Three patients experienced febrile neutropenia or infection preceding dose reduction (one TA6/TA6, one TA6/TA7 and one TA7/TA7). Nine patients discontinued IRI before tumour evaluation at the third cycle. The discontinuation was preceded by unacceptable toxicity in six patients and included grade ⩾3 diarrhoea in all patients, but none of them experienced neutropenic fever (one TA6/TA6, four TA6/TA7 and one TA7/TA7).

In the IRI regimen, two of three TA7/TA7 (67%) patients received a dose reduction during IRI treatment, compared to 17 and 16% of TA6/TA6 and TA6/TA7, respectively. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P-value for trend: 0.45). Most of the dose reductions occurred in cycle 2 or 3 and 89% (n=8) of these were owing to gastrointestinal toxicity grades ⩾3. Two patients (22%, TA6/TA6 and TA6/TA7) experienced also febrile neutropenia or infection preceding dose reduction. Five patients (all TA6/TA7) discontinued IRI before the first scheduled tumour evaluation; of these, two patients experienced unacceptable toxicity (diarrhoea grade 3).

Bivariate analysis of toxicity

We performed an explorative covariate analysis of patient characteristics (Table 1) and selected TS, ABCB1 and ABCG2 genotypes as they might confound associations of UGT1A1*28 with febrile neutropenia. We report here only those associations with P-values <0.05. Genotype distributions (Table 1) are in accordance with earlier publications (Cascorbi et al, 2001; Mandola et al, 2003, 2004; Lecomte et al, 2004; de Jong et al, 2004). Binary logistic regression of UGT1A1*28 with febrile neutropenia suggested that a performance status of 2 or a rectosigmoid tumour origin both significantly increased the risk of febrile neutropenia in the first cycle of IRI treatment (odds: 41.7, P=0.010 and odds: 6.5, P=0.030, respectively) in addition to the association of UGT1A1*28. A performance status of 2 increased the risk of febrile neutropenia at any time during IRI treatment 13.9-fold (P=0.022) and in bivariate logistic regression abolished the level of significance of the UGT1A1*28 association (odds for TA7/TA7: 18.5, P=0.128).

Discussion

We investigated three issues concerning UGT1A1*28 genotype and IRI use: (1) response rates by genotype, (2) association with febrile neutropenia and (3) dosage adjustments by genotype. We found that the TA7 allele and the TA7/TA7 genotype are associated with an increased risk of febrile neutropenia, in patients receiving IRI and CAPIRI, respectively. Furthermore, tumour response rates were not significantly different among UGT1A1 genotypes and TA7/TA7 patients tolerated the same number of IRI cycles and dosage compared to the other genotypes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the effects of UGT1A1*28 genotypes on IRI dose intensity using a 3-week regimen. It is also the first to study the association between UGT1A1 *28 and febrile neutropenia for IRI monotherapy. In our opinion, febrile neutropenia is a more relevant clinical end point as compared to (often uncomplicated) neutropenia, as it results in hospitalisation and is potentially lethal. The current results confirm the observed trend of an increased prevalence of severe haematological toxicity among TA7/TA7 patients (Innocenti et al, 2004). A similar study by Toffoli et al (2006) shows that haematological toxicity occurring in the first cycle (but not later cycles) was related to UGT1A1*28 genotype. However, we found that TA7/TA7 patients receiving CAPIRI experience a higher risk of febrile neutropenia at any time during treatment as well as in the first cycle. Additionally, our results indicate that the performance status may be a strong predictor of toxicity and patients with a performance status of 2 may experience an increased risk for febrile neutropenia during IRI treatment. In bivariate analysis, performance status was associated with febrile neutropenia occurring at any cycle, whereas UGT1A1*28 was not. Therefore, future pharmacogenetic studies associating febrile neutropenia may consider including performance status as a covariate.

We hypothesised that TA6/TA6 patients might obtain lower response rates owing to more effective SN-38 glucuronidation. If so, response rate can possibly be improved by increasing IRI dosage in these patients. Data on UGT1A1*28 and response to IRI-based chemotherapy are contradicting. Carlini et al (2005) report a non-significant trend for an improved response rate in TA7 homozygotes. Ando et al (2000) described that TA7 allele carriers are at risk of developing severe toxicity by IRI and as a result, they received lower dosages. The low-dosed patients showed a non-significant trend towards better response. Higher response rates for the TA7/TA7 genotype were also found by others (Toffoli et al, 2006). In contrast, Marcuello et al (2004) reported that patients with the UGT1A1*28 polymorphism receiving IRI did not have a higher response rate but experienced shorter overall survival. In our study, similar to others (Liu et al, 2008), we found that TA6/TA6 patients had no significantly different antitumour efficacy compared to patients with other UGT1A1 genotypes.

One would expect that TA7/TA7 patients received fewer numbers of cycles and lower RDI owing to more febrile neutropenia. Indeed, a recent study with 2-week IRI (Liu et al, 2008) found that the need for dose reduction was associated with the TA7/TA7 genotype, but this association was not found by others (Toffoli et al, 2006). However, in 3-week CAPIRI, diarrhoea, and not neutropenia, may be the primary dose-limiting toxicity (Carlini et al, 2005; Koopman et al, 2006). Indeed, nearly all dose reductions in cycles 2–3 in our study were preceded only by gastrointestinal toxicity. Likewise, most patients who discontinued IRI use within the first three cycles experienced severe (grade ⩾3) diarrhoea but not neutropenic fever. However, severe diarrhoea may occur more frequently in 3-week regimens with higher IRI dosages. In these regimens, the influence of febrile neutropenia (and the UGT1A1*28 polymorphism) on dose intensity may be less pronounced compared to the 2-week regimen.

In conclusion, we observed that the UGT1A1*28 genotype is associated with an enhanced risk of febrile neutropenia but not with IRI dose reductions. However, upfront dose reduction may result in a lower incidence of febrile neutropenia in these patients.

Acknowledgments

The Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) CAIRO study was supported by the CKTO (grant 2002–2007) and by unrestricted scientific grants from Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer. We would like to thank the following CAIRO team members for participating in the pharmacogenetic side-study: J van der Hoeven-Amstelveen; D Richel, B de Valk-Amsterdam; J Douma-Arnhem; P Nieboer-Assen; F Valster-Bergen op Zoom; G Ras, O Loosveld-Breda; D Kehrer-Capelle a/d IJssel; M Bos-Delft; H Sinnige, C Knibbeler-Den Bosch; W Van Deijk, H Sleeboom-Den Haag; E Muller-Doetinchem; E Balk-Ede; G Creemers-Eindhoven; R de Jong-Groningen; P Zoon-Harderwijk; J Wals-Heerlen; M Polee-Leeuwarden; M Tesselaar-Leiden; R Brouwer-Leidschendam; P de Jong, P Slee-Nieuwegein; C Punt, H Oosten-Nijmegen; M Kuper-Oss; M den Boer-Roermond; F de Jongh-Rotterdam; G Veldhuis-Sneek; D ten Bokkel Huinink-Utrecht and A van Bochove-Zaandam.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

Supplementary Material

References

- Abigerges D, Chabot GG, Armand JP, Herait P, Gouyette A, Gandia D (1995) Phase I and pharmacologic studies of the camptothecin analog irinotecan administered every 3 weeks in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 13: 210–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Saka H, Ando M, Sawa T, Muro K, Ueoka H, Yokoyama A, Saitoh S, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y (2000) Polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase gene and irinotecan toxicity: a pharmacogenetic analysis. Cancer Res 60: 6921–6926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Saka H, Asai G, Sugiura S, Shimokata K, Kamataki T (1998) UGT1A1 genotypes and glucuronidation of SN-38, the active metabolite of irinotecan. Ann Oncol 9: 845–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando Y, Ueoka H, Sugiyama T, Ichiki M, Shimokata K, Hasegawa Y (2002) Polymorphisms of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase and pharmacokinetics of irinotecan. Ther Drug Monit 24: 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous (1998) Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program Common toxicity criteria, version 2.0. National Cancer Institute, published online at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html

- Boyle P, Ferlay J (2005) Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann Oncol 16: 481–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlini LE, Meropol NJ, Bever J, Andria ML, Hill T, Gold P, Rogatko A, Wang H, Blanchard RL (2005) UGT1A7 and UGT1A9 polymorphisms predict response and toxicity in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine/irinotecan. Clin Cancer Res 11: 1226–1236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascorbi I, Gerloff T, Johne A, Meisel C, Hoffmeyer S, Schwab M, Schaeffeler E, Eichelbaum M, Brinkmann U, Roots I (2001) Frequency of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the P-glycoprotein drug transporter MDR1 gene in white subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 69: 169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong FA, Marsh S, Mathijssen RH, King C, Verweij J, Sparreboom A, McLeod HL (2004) ABCG2 pharmacogenetics: ethnic differences in allele frequency and assessment of influence on irinotecan disposition. Clin Cancer Res 10: 5889–5894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux M, Ychou M, Seitz JF, Bonnay M, Bexon A, Armand JP, Mahjoubi M, Mery-Mignard D, Rougier P (1999) Irinotecan combined with bolus fluorouracil, continuous infusion fluorouracil, and high-dose leucovorin every two weeks (LV5FU2 regimen): a clinical dose-finding and pharmacokinetic study in patients with pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 17: 2901–2908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti F, Undevia SD, Iyer L, Chen PX, Das S, Kocherginsky M, Karrison T, Janisch L, Ramirez J, Rudin CM, Vokes EE, Ratain MJ (2004) Genetic variants in the UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 gene predict the risk of severe neutropenia of irinotecan. J Clin Oncol 22: 1382–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L, Das S, Janisch L, Wen M, Ramirez J, Karrison T, Fleming GF, Vokes EE, Schilsky RL, Ratain MJ (2002) UGT1A1*28 polymorphism as a determinant of irinotecan disposition and toxicity. Pharmacogenomics J 2: 43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L, Hall D, Das S, Mortell MA, Ramirez J, Kim S, Di Rienzo A, Ratain MJ (1999) Phenotype-genotype correlation of in vitro SN-38 (active metabolite of irinotecan) and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver tissue with UGT1A1 promoter polymorphism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 65: 576–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L, King CD, Whitington PF, Green MD, Roy SK, Tephly TR, Coffman BL, Ratain MJ (1998) Genetic predisposition to the metabolism of irinotecan (CPT-11). Role of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase isoform 1A1 in the glucuronidation of its active metabolite (SN-38). in human liver microsomes. J Clin Invest 101: 847–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, Wals J, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FL, de Jong RS, Rodenburg CJ, Vreugdenhil G, kkermans-Vogelaar JM, Punt CJ (2006) Randomised study of sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer, an interim safety analysis. A Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG). phase III study. Ann Oncol 17: 1523–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman M, Antonini NF, Douma J, Wals J, Honkoop AH, Erdkamp FL, de Jong RS, Rodenburg CJ, Vreugdenhil G, Loosveld OJ, van BA, Sinnige HA, Creemers GJ, Tesselaar ME, Slee PH, Werter MJ, Mol L, Dalesio O, Punt CJ (2007) Sequential versus combination chemotherapy with capecitabine, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer (CAIRO): a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 370: 135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte T, Ferraz JM, Zinzindohoue F, Loriot MA, Tregouet DA, Landi B, Berger A, Cugnenc PH, Jian R, Beaune P, Laurent-Puig P (2004) Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism predicts toxicity in colorectal cancer patients receiving 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 10: 5880–5888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Chen PM, Chiou TJ, Liu JH, Lin JK, Lin TC, Chen WS, Jiang JK, Wang HS, Wang WS (2008) UGT1A1*28 polymorphism predicts irinotecan-induced severe toxicities without affecting treatment outcome and survival in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 112: 1932–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Muller-Weeks S, Cesarone G, Yu MC, Lenz HJ, Ladner RD (2003) A novel single nucleotide polymorphism within the 5′ tandem repeat polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase gene abolishes USF-1 binding and alters transcriptional activity. Cancer Res 63: 2898–2904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandola MV, Stoehlmacher J, Zhang W, Groshen S, Yu MC, Iqbal S, Lenz HJ, Ladner RD (2004) A 6 bp polymorphism in the thymidylate synthase gene causes message instability and is associated with decreased intratumoral TS mRNA levels. Pharmacogenetics 14: 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcuello E, Altes A, Menoyo A, Del Rio E, Gomez-Pardo M, Baiget M (2004) UGT1A1 gene variations and irinotecan treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 91: 678–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrouche Y, Extra JM, Abigerges D, Bugat R, Catimel G, Suc E, Marty M, Herait P, Mahjoubi M, Armand JP (1997) High dose-intensity of irinotecan administered every 3 weeks in advanced cancer patients: a feasibility study. J Clin Oncol 15: 1080–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoluzzi L, Singh AS, Price DK, Danesi R, Mathijssen RH, Verweij J, Figg WD, Sparreboom A (2004) Influence of genetic variants in UGT1A1 and UGT1A9 on the in vivo glucuronidation of SN-38. J Clin Pharmacol 44: 854–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullarkat ST, Stoehlmacher J, Ghaderi V, Xiong YP, Ingles SA, Sherrod A, Warren R, Tsao-Wei D, Groshen S, Lenz HJ (2001) Thymidylate synthase gene polymorphism determines response and toxicity of 5-FU chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics J 1: 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punt CJ (2004) New options and old dilemmas in the treatment of patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 15: 1453–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NF, Figg WD, Sparreboom A (2006) Pharmacogenetics of irinotecan metabolism and transport: an update. Toxicol In Vitro 20: 163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, Van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwynther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Nat Cancer Inst 92: 205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toffoli G, Cecchin E, Corona G, Russo A, Buonadonna A, D’Andrea M, Pasetto LM, Pessa S, Errante D, De Pangher V, Giusto M, Medici M, Gaion F, Sandri P, Galligioni E, Bonura S, Boccalon M, Biason P, Frustaci S (2006) The role of UGT1A1*28 polymorphism in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of irinotecan in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 3061–3068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ychou M, Raoul JL, Desseigne F, Borel C, Caroli-Bosc FX, Jacob JH, Seitz JF, Kramar A, Hua A, Lefebvre P, Couteau C, Merrouche Y (2002) High-dose, single-agent irinotecan as first-line therapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 50: 383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.