Abstract

A vaccine formula comprised of five recombinant human intra-acrosomal sperm proteins was innoculated into female monkeys to test whether specific antibodies to each component immunogen could be elicited in sera and whether antibodies elicited by the vaccine affected in vitro fertilization. Acrosomal proteins, ESP, SLLP-1, SAMP 32, SP-10 and SAMP 14, were expressed with his-tags, purified by nickel affinity chromatography and adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide. Five female cynomolgus monkeys were inoculated intramuscularly 3 times at monthly intervals. All five monkeys developed both IgG and IgA serum responses to each recombinant immunogen on Western blots. Each serum stained the acrosome of human sperm and bound to the cognate native protein on Western blots of human sperm extracts. By ELISA, all monkeys developed IgG to each immunogen, with the highest average absorbance values to ESP, SAMP 32 and SP-10, followed by lower values for SLLP-1 and SAMP 14. IgA was also generated to each component immunogen with the highest average absorbance values to SLLP-1 and SP-10. For antigens that induced an IgA response, the duration of the IgA response was longer than the IgG response to the same antigens. This study supports the concept that a multivalent contraceptive vaccine may be administered to female primates evoking both peripheral (IgG) and mucosal (IgA) responses to each component immunogen following an intramuscular route of inoculation with a mild adjuvant, aluminum hydroxide, approved for human use.

Keywords: immune response, human sperm antigen, monkey, IgG, IgA

1. Introduction

Immunization of females with sperm-specific antigens has been considered the basis of a new means of contraception. In practice, however, the development of a contraceptive vaccine for use by women has been hampered by two issues. First, no single germ cell-specific antigen has yet proven to have sufficient efficacy in vivo in non-human primates to warrant a human trial (Thau and Sundaram, 1980; Goldberg et al., 1981; O'Hern et al., 1995, 1997; Paterson et al., 1999). Second, many adjuvants that might increase the immunogenicity of molecules are not yet approved for use in humans (Thau and Sundaram, 1980; Goldberg et al., 1981; Jones et al., 1988; Talwar et al., 1990; Griffin, 1994; O'Hern et al., 1995, 1997; Stevens, 1996; Paterson et al., 1999).

Several steps in the cascade of events of fertilization are, in theory, amenable to immunological interdiction by vaccination, including sperm transport through the female reproductive tract and sperm interactions with the egg vestments. Candidate vaccinogens include those accessible to antibodies in the oviducts at the time of initial binding of the sperm plasma membrane to the zona pellucida (ZP), molecules exposed following the acrosome reaction (AR), and molecules that mediate sperm fusion with the egg membrane and subsequent events of sperm internalization. The sperm plasma membrane fuses with the outer acrosomal membrane (OAM) during the AR, the acrosomal matrix is exposed and the inner acrosomal membrane (IAM) subsequently becomes the limiting membrane of the sperm head. Following the AR at the zonal surface, the IAM is generally considered to bind to the ZP (a process referred to as secondary binding) accompanied by hydrolysis of a passage (the fertilization channel) through the ZP. The equatorial segment (ES) of the acrosome remains intact following the AR, and it is generally thought that the plasma membrane overlying the ES binds to and fuses with the egg plasma membrane (Bedford et al., 1979; Yanagimachi, 1994; Wassarman, 1995). The rationale for using acrosomal antigens as contraceptive vaccinogens, particularly molecules which may be directly in contact with egg components during sperm-egg interaction, has been underscored by data showing that a single intra-acrosomal protein found in humans and mice, Izumo, is necessary for sperm fusion to the egg membrane. After knocking out the Izumo gene, homozygous male F2 mice were infertile and antibodies to human Izumo inhibited in vitro fertilization using human sperm and hamster eggs (Inoue et al., 2005).

The rationale for working toward a vaccine comprised of multiple acrosomal antigens that have the potential for interrupting the fertilization process is that a multivalent vaccine may evoke a greater anti-fertility effect in females than immunization with a single sperm antigen. Although titers to a given epitope may wane with antibody catabolism [the half-life of immunoglobulin in primates is approx. 20 days], the overall number of different antibodies targeted to the sperm surface is predicted to be greater. Further, in an outbreed population such as humans, variability in host responsiveness to any single epitope is likely to be present. With administration of multiple antigens, there is a greater possibility of activating the host individual’s immune system to produce a range of antibodies to surface exposed acrosomal epitopes.

Before addressing the issue of efficacy of sperm immunogens for contraception, we elected to test a combination of sperm antigens in an immunogenicity study in cynomolgus monkeys to determine whether the animals would make antibodies to all of the antigens when they were administered simultaneously or whether antigen interference, either physical or chemical, would mask or diminish immune responsiveness. Of the five antigens selected for this study, four are associated with the acrosome both before and after the acrosome reaction (AR): ESP, SAMP 32, SAMP 14 and SP-10 (Herr et al., 1990a,b; Kurth et al., 1991; Foster and Herr, 1992; Foster et al., 1994; Wolkowicz et al., 1996, 2003; Hao et al., 2002; Shetty et al., 2003). The fifth antigen, SLLP-1, is found in the acrosomal matrix before the AR but its location after the AR is unclear (Mandal et al., 2003). Other criteria for selection were testis-specificity, post-meiotic expression, iso-antigenicity and the proven ability of antibodies or recombinant proteins to block sperm-egg binding and/or fusion in vitro in the xenoassay using human sperm and hamster eggs (hamster egg penetration test,HEPT) (Kurth et al., 1991; Coonrod et al., 1996; Wolkowicz et al., 1996, 2003; Hao et al., 2002; Mandal et al., 2003; Shetty et al., 2003). Thus, antibodies to all the human immunogens chosen for this study have provided evidence for inhibitory effects on fertilization in vitro. Although the homology and identity of a monkey ortholog to several of the human proteins used in this study has not yet been ascertained, Macaca fascicularis was used as a primate model because the homology and identity of its SP-10 ortholog is 85%, and its ESP ortholog is 93 and 92%, respectively, compared to considerably lower similarities to mouse and rat orthologs.

The scarcity of adjuvants approved for use in the human population has severely restricted options for the formulation of a contraceptive vaccine. Normally in a laboratory setting, animals are administered antigens using adjuvants that will maximize the amount of antibody produced. Some of those adjuvants are oil/water emulsions, such as Freund’s complete and incomplete adjuvant, immunostimulatory substances like muramyl dipeptide derivatives, saponins, monophosphoryl Lipid A, cytokines, CpG oligos, diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, cholera toxin or combinations of these. Liposomes and polymer microspheres have been used with increasing frequency in the hopes of developing alternative routes (intranasal) of administration of vaccines. However, adverse events can be associated with vaccine adjuvants, including injection site granulomas, abscesses, arthritis, amyloidosis, allergic reactions, systemic toxicity and pyrogenicity (Gupta et al., 1993; Macy, 1997; Singh and O'Hagan, 1999; Scheibner, 2000). Thus, in contrast to the array of adjuvants available for laboratory use, safety considerations have so far limited universally approved adjuvants for vaccines intended for human use to aluminum compounds. Therefore, to obtain preclinical data, this study was conducted in a primate model using a multicomponent vaccine consisting of human recombinant acrosomal proteins adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide. Specific aims of the study were: 1) to determine whether sperm antigens, when administered as a mixture, were immunogenic in cynomolgus monkeys; 2) to determine whether serum antibodies raised to the recombinant proteins also reacted with the endogenous sperm proteins; 3) to determine whether IgG and IgA antibodies would be elicited; 4) to determine the approximate duration of the antibody response, and 5) to determine whether serum from immunized monkeys had an effect on sperm-egg interaction in vitro.

2. Materials and Methods

Study overview: sera were collected for up to 25 weeks post-immunization and analyzed by immunofluorescence and Western blotting for the presence of antigen-specific IgG and IgA antibodies against human sperm and sperm extracts. Sera were also tested against the individual recombinant proteins by Western analysis. To determine relative amounts of IgG and IgA antigen-specific antibodies, pre-immune and immune fluids were compared by ELISA against each antigen.

2.1. Expression of recombinant proteins

Antigens were generated from Ni-NTA purified human recombinant proteins expressed in the pET28b vector in E. coli (Reddi et al., 1994; Hao et al., 2002; Mandal et al., 2003; Shetty et al., 2003; Wolkowicz et al., 2003).

2.2. Silver staining

To visualize the products used for immunizations, 0.5µg of each purified recombinant protein was electrophoresed through a 12% SDS-PAGE gel in individual lanes as well as in a lane containing a mixture of 0.5µg of each protein. Gels were stained with silver nitrate according to the method of Shevchenko (1996).

2.3. Animals

Five regularly cycling female Macaca fascicularis were used in this study. Monkeys were pair-housed in the Center for Comparative Medicine at the University of Virginia (UVA). They were fed a diet of Purina monkey chow, fruits, vegetables, meal worms and moth larvae (Primate Products, Miami, FL, USA) and grains. Access to water was unrestricted. Their room was temperature controlled and kept on a 12L:12D cycle. All procedures performed on the monkeys were approved by the UVA IACUC and followed the Animal Welfare Act regulations and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals recommendations. Four male Macaca fascicularis were used as semen donors for initial assays to determine whether antibodies to the individual recombinant proteins and female immune sera reacted with fixed and extracted monkey sperm in a manner similar to reactivity found on human sperm.

2.4. Immunizations and sample collections

Each of the five female monkeys was inoculated at two sites, both quadriceps muscles, 3 times at monthly intervals with 1ml volumes of aluminum hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and PBS, 1:1, containing 200ug of each protein for the primary immunization or 100ug of each protein for the boosters. Two pre-immune serum samples were collected from each monkey. After the primary immunization, sera were collected weekly for 13 weeks, then biweekly for an additional 3 months.

2.5. Monkey sperm collections

Sperm for immunoassays were obtained from semen collected from the male monkeys. Monkeys were injected with 5mg/kg ketamine and electro-ejaculated with a rectal probe. An average of 3 pulses was administered at 5–7 volts using a Standard Precision ejaculator set (Denver, CO). Semen samples were collected in 15ml centrifuge tubes, washed once in Ham’s F-10 medium and were used fresh for immunocytochemistry.

2.6. Human sperm collections

Human semen samples were obtained from healthy donors by masturbation following 3–4 days of sexual abstinence. Written consent was obtained prior to the donation. Ejaculates with normal semen volume, sperm count and motility were used in this study. After liquefaction, semen was washed three times in Ham’s F-10 medium. Sperm was separated from seminal plasma by centrifugation at 1258g for 10 minutes. Sperm were either stored at −70°C for Western blots or used fresh for immunocytochemistry.

2.7. Immunofluorescence of monkey sperm

2.7.1. Staining of monkey sperm with rat antisera

Monkey sperm were air-dried on immunofluorescence slides (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Sperm were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated in PBS/10% normal goat serum (NGS) to block non-specific binding. Slides were incubated with pre-immune or immune rat antisera to ESP, SAMP 32, SAMP 14 or SLLP-1 for 1h. ESP and SAMP32 antisera were used at a 1:100 dilution, and SAMP 14 and SLLP-1 antisera were used at a 1:25 dilution. Slides were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated for 1h with a 1:200 dilution of goat anti-rat fluorescein-labeled IgG. Slides were then washed and examined under a Zeiss microscope equipped with an SV-microsystems digital camera. A control murine monoclonal antibody, MHS-10, to the human acrosomal antigen SP-10 was used also as a acrosomal biomarker. Sperm were methanol-fixed and visualized using FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG and examined using a Zeiss Axioplan (Oberkochen, Germany) fluorescence microscope with DIC imaging.

2.7.2. Staining of monkey sperm with monkey antisera

Monkey sperm were air-dried on slides, fixed in methanol for 30 min, and washed and blocked as above. Each slide was incubated with one of the female monkey pre-immune or immune sera for 1h at a 1:500 dilution except monkey R, for which a 1:200 dilution was used. Slides were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated for 1h with a 1:200 dilution of goat-anti monkey fluorescein-labeled IgG. Slides were then washed and examined under a Zeiss microscope equipped with an SV-microsystems digital camera. Immunofluorescent results presented in figures used the optimal conditions determined from among variations in fixation and primary antibody dilutions.

2.7.3. Immunofluorescent staining of human sperm with monkey antisera

Human sperm were air-dried on slides, fixed in methanol for 30 min, and washed and blocked PBS/10% NGS. Slides were incubated with preimmune and immune monkey sera at 1:50 for 1h, washed 3x in PBST, and incubated in either goat anti-monkey fluorescein-labeled IgG or IgA for 1–2h in the dark. Slides were then washed and examined as above.

2.8. Western blots

To determine whether post-immunization sera contained antibodies to human sperm, samples were extracted in 1% SDS for 60–120 min at 4°C with agitation. The samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1258g and pellets resuspended in reducing buffer (Mesna M1511; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and boiled prior to use. One mg of human sperm extract was electrophoresed through preparative 0.1%SDS/12% PAGE. Gels were transferred in a transblot cell (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, USA) for 1h at 1 amp to nitrocellulose membranes and processed for Ponceau S staining and immunoblot assays. Blots were cut into strips and probed with monkey pre-immune or immune sera collected ten days after the first boost. Polyclonal antibodies previously made in rats to ESP, SAMP 32, SAMP 14, SLLP-1 and MHS10 were used as positive controls (refs). Negative controls were HRP-conjugated secondary goat anti-monkey IgG or IgA (KPL; Gaithersburg, MD, USA), goat anti-rat IgG/M and goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Laboratories; West Grove, PA, USA). Blocking solution to reduce nonspecific binding was 1% NGS (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA, USA)/10% dry milk/ phosphate-buffered saline (137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 4.3mM Na2HPO4 and 1.4mM KH2 PO4)/Tween 20 (PBST). To determine whether monkey immune sera responded to each of the recombinant proteins, 2ug of each recombinant protein (or 10ug in the case of SLLP-1) were run out on separate preparative gels and processed as above. Rat and monkey sera were used at 1:500 with secondary antibodies at 1:5000 on recombinant protein blots. For Western blots of sperm extracts, rat and monkey sera were used at 1:1000 and all secondary antibodies at 1:10000 dilutions. Color was developed using TMB membrane substrate (KPL; Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

2.9. ELISA

Serum antibody absorbance values to each of the five recombinant proteins were determined by coating wells on Immulon 4 HBX microtiter plates (S25-351-01; Fisher Scientific; Newark, DE, USA) with 50ng of a recombinant protein in 50µl of carbonate-bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6, and incubating the solution overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBST using a Titertek Plus plate washer (M96; 78-461-00; ICN Biomedicals Inc., Costa Mesa, CA, USA). To reduce nonspecific binding, wells were blocked with PBST/1% NGS. Preimmune and immune sera were serially diluted across the plate, beginning at 1:100 and ending at 1:102,400 or 1:204,800, in triplicate for each recombinant antigen and each monkey. Secondary antibody was goat anti-monkey IgG conjugated to HRP at 1:5000 dilution and 2,2’-azino-bis [3-ethylbenz-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid] (ABTS)/0.3% H2O2 was used as the chromagen. When the secondary antibody was goat anti-monkey IgA, serial dilutions began at 1:25 and ended at 1:1600. Absorbance values were determined on Titertek Multiscan MCC/340 MKII plate reader at a wavelength of 414 or 405nm. To correct for variations between plates, absorbance readings for all samples were normalized on each plate to the value for a standard serum from rats immunized with individual recombinant proteins used in the formulation injected into the monkeys or monoclonal antibodies made to individual antigens, which was considered to be 1. Mean absorbances were calculated for the five monkeys at weeks 0 to 25. Differences between means of preimmune and immune sera were compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Duncan, and Student-Newman Keuls multiple range tests. For the multiple range tests, p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the computer program SPSS for Windows.

2.10. Hamster egg penetration test (HEPT)

Gamete incubations were carried out in microdrops under paraffin oil at 37°C and 5% CO2. Ejaculated human semen was allowed to liquefy for at least 30 min. Five hundred microliters of the ejaculate was placed under 2ml of BWW medium containing 5mg/ml human serum albumin (HSA, Sigma) for 60–90 min and the sperm were allowed to swim-up. The swim-up sperm were then washed twice by centrifugation (8 min at 600g) in 8ml volumes of BWW/HSA in 15ml centrifuge tubes. Sperm were capacitated at a concentration of 20 × 10 6 sperm/ml overnight in 250µl drops of BWW containing 30mg/ml HSA. Ova were obtained from Golden Syrian hamsters by superovulation according to Johnson et al. (1990). Cumulus cells were removed by treating eggs with 0.05% hyaluronidase (Sigma) for 3 min. The oocytes were then pooled and washed through 20µl drops of media using a pulled, heat-polished pasteur pipette. Zona pellucidae were removed by treating eggs with 1mg/ml trypsin for 30 sec followed by 5 washes. The eggs were then randomly allotted into treatment groups.

Following overnight capacitation, 2 × 10 6 sperm/ml were treated for 1h in a 20µl drop containing a 1:10 dilution of pre-immune or immune monkey serum in BWW containing 30mg/ml HSA. Following sperm/serum incubation, zona-free hamster oocytes were added directly to the sperm suspension and the gametes were co-incubated for 3h. Following gamete co-incubation, loosely bound sperm were removed from the oocytes by gentle pipetting.

The eggs were then treated with 1mM acridine orange in 3% DMSO (Sigma) for 15 sec to stain the chromatin and washed through three 20µl microdrops. To quantitate binding, oocytes were placed between a microscope slide and an elevated coverslip, and the number of sperm bound per oocyte recorded. The number of sperm fused per egg was scored by counting the number of acridine orange-stained decondensed sperm heads within each oocyte using fluorescent microscopy. The assay was repeated three times for each monkey serum used. Experimental and control group averages were reported as means ± SE. Student’s t-test was used to identify differences between pre-immune and post-immune sera in the number of bound and fused spermatozoa. P < 0.05 was considered to be significantly significant.

3. Results

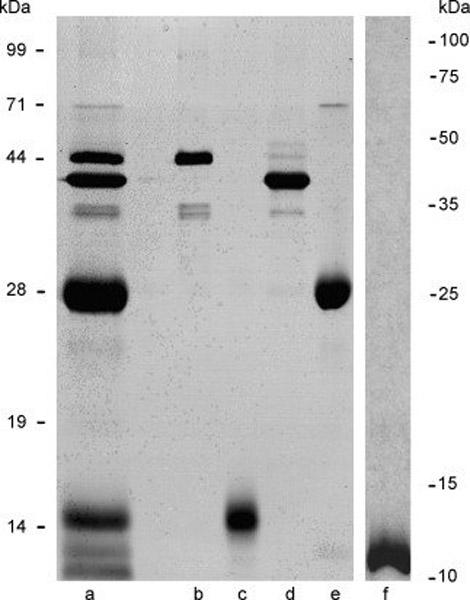

3.1. Visualization of immunogen preparation

Silver-stained recombinant proteins used for immunizations showed highly purified preparations of SP-10, SLLP-1, ESP, SAMP 32 and SAMP 14 (Fig. 1). The major bands of SP-10 migrated at ~ 44kDa, of ESP at approximately 36–38kDa and of SAMP 32 at 28kDa. A single band was seen at ~15kDa for SLLP-1 and a single band representing SAMP 14 migrated below the expected 14kDa. Immunostaining a blot of a portion of the gel shown in Figure 1 with antibodies to each recombinant protein confirmed the identity of each of the major bands (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Silver-stained 12% SDS-PAGE gel of vaccine formulation used for monkey immunizations (a) and individual recombinant protein components showing relative purity. Lanes a, vaccine formulation at 2.5µg total protein; b, 0.5µg recombinant human SP-10; c, 0.5-g recombinant human SLLP-1; d, 0.5µg recombinant human ESP; e, 0.5µg recombinant human SAMP 32; f, 0.5µg recombinant human SAMP 14.

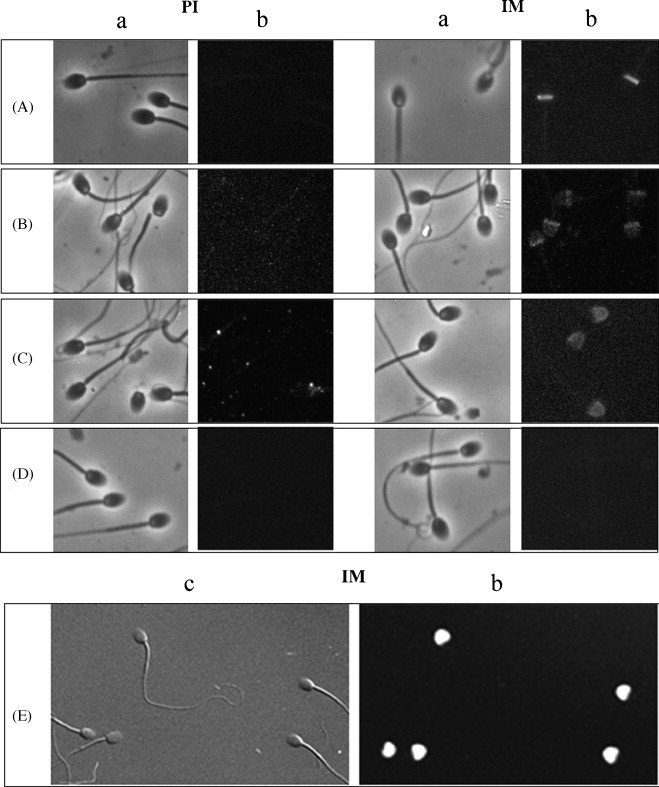

3.2. Antibody recognition of the endogenous proteins in monkey sperm

To determine whether the monkey orthologs of the five human proteins were located in the acrosome of monkey sperm, immunofluorescent staining using rat or mouse antiserum to each human recombinant protein was performed. The presence of each antigen and its localization to a particular aspect of the monkey sperm acrosome was confirmed to be identical to that of human sperm in all cases but SLLP-1 (Fig. 2). Rat anti-ESP stained the equatorial segment of the acrosome, rat anti-SAMP 32 bound diffusely to the acrosomal cap and more intensely to the equatorial region, and rat anti-SAMP 14 reacted with the acrosomal cap. MHS-10 reactivity for SP-10 was confined to the acrosomal cap. Antiserum to human SLLP-1 did not bind to monkey sperm using this method.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescent staining of monkey sperm using rat antiserum to each human recombinant protein or anti-human mouse monoclonal antibody. A, rat anti-ESP stained the equatorial segment of the acrosome; B, rat anti-SAMP 32 bound diffusely to the acrosomal cap and more intensely to the equatorial region; C, rat anti-SAMP 14 reacted with the acrosomal cap; D, anti-serum to SLLP-1 did not stain monkey sperm using this method; E, monoclonal antibody MHS-10 reacted with SP-10 on the acrosomal cap. PI, pre-immune sera; IM immune sera; a, phase contrast image; b, fluorescent image; c, differential interference contrast image. Magnification 1000x

3.3. Immunogenicity of human recombinant proteins using aluminum hydroxide as adjuvant

3.3.1. Recognition of monkey sperm by monkey sera

To test whether the sera of monkeys immunized with the recombinant human sperm protein formulation reacted with endogenous proteins in monkey sperm, immunofluorescent staining was employed using anti-monkey IgG secondary antibody. Immune serum from each monkey reacted specifically with only the monkey acrosome in close to 100 % of sperm analyzed (Fig.3). Preimmune sera from each monkey were negative for reactivity to monkey sperm except for sperm from monkey S, which reacted with the equatorial segment.

Figure 3.

Sera from immunized monkeys reacted with monkey sperm. A, monkey A; B, monkey B; C, monkey I; D, monkey R; E, monkey S. With the exception of monkey S, which showed some equatorial staining, pre-immune sera staining of the sperm was negative. Immune sera from all monkeys reacted with the acrosomal cap of monkey sperm. F, secondary antibody alone was negative. PI, pre-immune sera; IM, immune sera; a, phase contrast image; b, fluorescent image. Magnification 1000x.

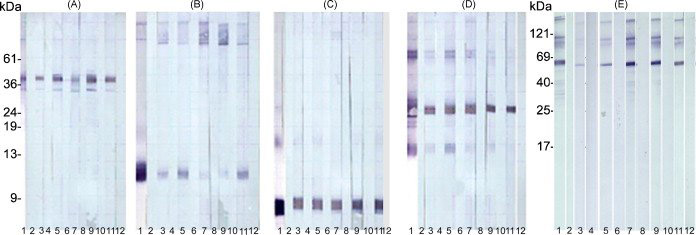

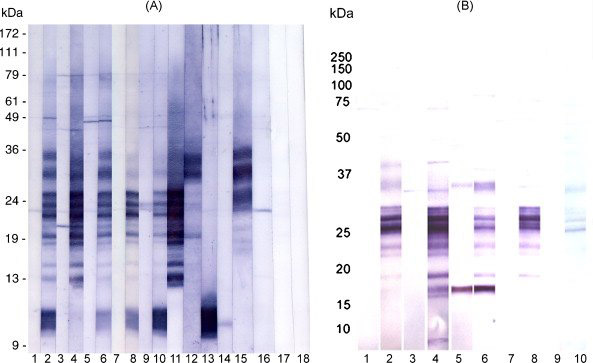

3.3.2. Western blots of individual recombinant proteins with monkey sera

Whether or not the monkeys responded to the human recombinant proteins was ascertained by probing Western blots with pre-immune and immune sera from the five monkeys. All monkeys reacted to all of the recombinant proteins with varying degrees of intensity when 2ug of each protein were run on gels and blotted to nitrocellulose, except for SLLP-1 which required loading of more protein to elicit a discernable reaction (Fig. 4). For each protein, reactive bands recognized by monkey sera co-migrated with bands stained by positive control polyclonal rat sera (anti-ESP, -SAMP 32, -SAMP 14, -SLLP-1) and MHS-10 (anti-SP-10). All pre-immune and secondary antibody alone controls were negative.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of immunoreactivity to individual recombinant antigens with pre-immune and immune sera. All monkeys reacted to each of the recombinant proteins. Curtain gels used in Western blotting for A, reESP; B, reSAMP 14; C, reSLLP-1; D, reSAMP 32; E, reSP-10. Lanes 1, positive controls; 2, secondary only controls; 3, monkey R pre-immune serum; 4, monkey R immune serum; 5, monkey A pre-immune serum; 6, monkey A immune serum; 7, monkey B pre-immune serum; 8, monkey B immune serum; 9, monkey I pre-immune serum; 10, monkey I immune serum; 11, monkey S pre-immune serum; 12, monkey S immune serum. In the case of each recombinant protein, reactive bands recognized by monkey immune sera co-migrated with bands stained by positive control polyclonal rat sera or monoclonal antibody MHS-10. All pre-immune and secondary antibody alone controls were negative.

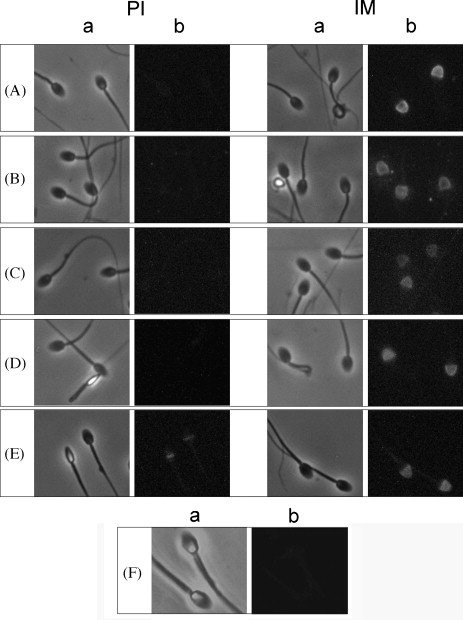

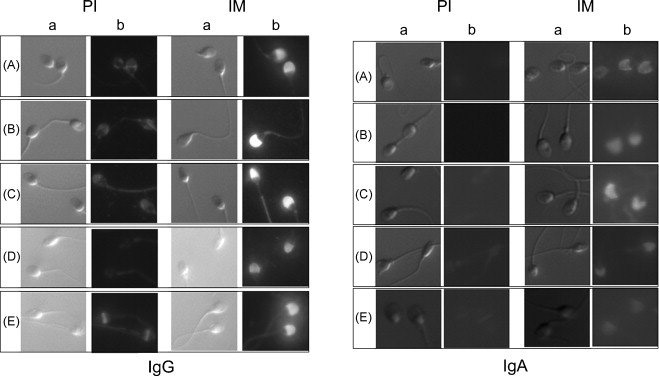

3.3.3. Immunofluorescent recognition of human sperm by monkey sera

A 1/500 dilution of immune sera from all monkeys reacted with the acrosomal cap of human sperm when anti-monkey IgG was used as the secondary antibody. When the secondary antibody was anti-monkey IgA, reactivity of monkey sera was confined to the acrosome but with less intensity and uniformity than found with the IgG antibody (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Immunfluorescence of sera reacted with human sperm. The acrosomal cap was stained with immune serum [1/500] from each monkey when anti-monkey IgG was used as the secondary antibody. When the secondary antibody was anti-monkey IgA, reactivity of monkey sera was confined to the acrosome but with less intensity and uniformity than found with the IgG antibody. Secondary antibodies alone were negative (data not shown). A, monkey A; B, monkey B; C, monkey I; D, monkey R; E, monkey S; pre-immune sera (PI); immune sera (IM); differential interference contrast image (a); fluorescent image (b). Magnification 1000x

3.3.4. Western blots of human sperm extract with monkey sera

To determine whether the monkeys’ sera bound to human sperm extracts, Western blots were exposed to monkey sera as well as polyclonal rat sera and MHS-10 (Fig. 6A and B). All monkey sera contained IgG immunoglobulins (A) that stained bands which co-migrated with bands defining each of the human sperm proteins. The major bands stained by monkey immune sera were between ~ 9 and 12kDa, comparable to bands stained by rat anti-SAMP 14 and -SLLP-1, and between ~ 13 and 36kDa, similar to all bands identified by positive control antibodies to SP-10, SAMP 32 and ESP. Each monkey responded with some variability in intensity to each antigen. For example, monkey R serum reacted best with bands between 9 and 12kDa and ~ 19 – 27kDa, serum from monkey B stained bands between ~ 13 and 36kDa most intensely, monkey A and monkey I responded well to the lowest bands as well as those between 19 and 36kDas and serum from monkey B stained very much like that from A. Serum from S reacted best with 9–12kDa bands and those at ~ 22–25kDa. Monkeys A and B responded with immunoglobulin A to bands between ~16–38kDa, monkeys I and R to bands between ~18–32kDa, and serum from monkey S responded faintly to bands between ~25–32kDa (B). Using this method, only serum from monkey B reacted clearly with a band below 10kDa.

Figure 6.

Western blot analysis of human sperm extracts reacted with monkey sera and probed for IgG (A) or IgA (B) antibodies. Lanes 1, monkey A pre-immune serum; 2, monkey A immune serum; 3, monkey B pre-immune serum; 4, monkey B immune serum; 5, monkey I pre-immune serum; 6, monkey I immune serum; 7, monkey R pre-immune serum; 8, monkey R immune serum; 9, monkey S pre-immune serum; 10, monkey S immune serum; 11, MHS-10; 12, rat anti-ESP; 13, rat anti-SAMP 14; 14, rat anti-SLLP-1; 15, rat anti-SAMP 32; 16, anti-monkey IgG alone; 17, anti-mouse IgG alone; 18, anti-rat IgG alone. (A) All monkeys responded with IgG immunoglobulins to bands which co-migrated with bands defined by rat or mouse antibodies to each of the recombinant human antigens; bands were between 9 and 13kDa (SLLP-1 and SAMP 14) and 13–36kDa (SP-10, ESP and SAMP 32). Bands for SLLP-1 and SAMP 14 overlapped in size as did bands for the larger 3 proteins. (B) Monkeys A, B and I responded with immunoglobulin A to bands of sizes corresponding to some of the SP-10-reactive bands, ESP and/or SAMP 32, and monkey B serum reacted faintly to a band in the size range seen in SAMP 14 and SLLP-1. Monkeys R and S immune sera stained fewer and, in the case of S, very faint bands in the SP-10 molecular weight range. Preimmune serum from monkey I bound very strongly to a band at ~ 18kDa which was also seen in monkey I immune serum.

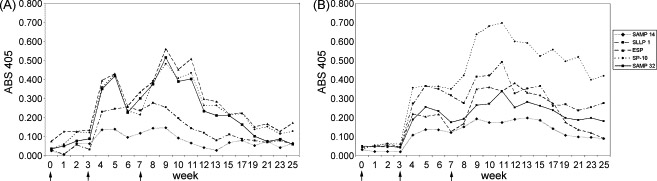

3.3.5. ELISA analysis of IgG antibody response

ELISA data were analyzed to determine the relative magnitude and duration of the IgG antibody responses. Absorbance values for serum dilutions at 1:1600 were chosen to represent these data because it was at the higher end of dilutions which showed no prozone effect (high-dose hook effect) in which the presence of excess antibody can inhibit binding to antigen. The mean absorbance values to each antigen at week 0 (pre-immune) through week 25 post-primary injection are shown in Figure 7 A. The mean secondary responses peaked at week 5 post-primary injection and the mean tertiary responses peaked at week 9 after the primary injection. These responses illustrate a classical reaction to immunization in which successive exposures to the immunogens resulted in more rapid and robust increases in antibodies indicative of anemnestic responses after the first and second booster injections.

Figure 7.

ELISA analysis of serum IgG and IgA antibody responses of all five monkeys (means) to each recombinant antigen. (A) Mean serum IgG antibodies for each antigen at each week that sera were collected. Peak responses occurred at week 5 after the first booster injection and week 9 after the second booster. Arrows indicate vaccine injections. See Table 1 for numerical values and standard errors. (B) Mean serum IgA antibodies for each antigen at each week that sera were collected. Peak responses occurred at week 5 after the first booster injection and week 11 after the second booster. Arrows indicate vaccine injections. See Table 2 for numerical values and standard errors.

Comparison of mean absorbance values between pre-immune (week 0) and immune sera at 1:1600 showed significant differences by ANOVA at p < 0.05 for each antigen. Subsequent application of Student-Neuman-Kuel’s and Duncan’s multiple range test (Table 1) indicated that there were significant differences between weeks 0 and weeks following the first and second boosters by Duncan’s MRT for all antigens. Using a more restrictive Student-Neuman-Kuel’s MRT, the same was true for SLLP-1, SAMP 14 and SP-10 while week 9 was the only week showing a significant difference from preimmune values for ESP and SAMP 32.

Table 1.

Mean IgG absorbance values that are significantly different from pre-immune values for each component of the vaccine.

| Week | Anti-SP-10 | Anti-ESP | Anti-SAMP-32 | Anti-SAMP-14 | Anti-SLLP-1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard error |

Statistica l test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

||

| 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 0.359 | 0.049 | a b | 0.393 | 0.163 | b | 0.349 | 0.138 | b | 0.134 | 0.018 | b | 0.228 | 0.063 | a b | |

| 5 | 0.426 | 0.082 | a b | 0.429 | 0.197 | b | 0.417 | 0.140 | b | 0.138 | 0.025 | a b | 0.245 | 0.079 | a b | |

| 6 | 0.236 | 0.057 | b | 0.094 | 0.017 | b | 0.253 | 0.061 | a b | |||||||

| 7 | 0.213 | 0.045 | b | 0.116 | 0.033 | b | 0.236 | 0.059 | a b | |||||||

| 8 | 0.391 | 0.048 | a b | 0.389 | 0.049 | b | 0.374 | 0.103 | b | 0.142 | 0.046 | a b | 0.276 | 0.047 | a b | |

| 9 | 0.481 | 0.076 | a b | 0.559 | 0.069 | a b | 0.515 | 0.130 | a b | 0.145 | 0.056 | a b | 0.254 | 0.038 | b | |

| 10 | 0.418 | 0.083 | a b | 0.460 | 0.095 | b | 0.387 | 0.120 | b | 0.196 | 0.062 | |||||

| 11 | 0.434 | 0.098 | a b | 0.508 | 0.109 | b | 0.402 | 0.120 | b | |||||||

| 12 | 0.262 | 0.048 | b | |||||||||||||

| 13 | 0.262 | 0.049 | b | |||||||||||||

| 15 | 0.212 | 0.037 | b | |||||||||||||

| 17 | ||||||||||||||||

| 19 | ||||||||||||||||

| 21 | ||||||||||||||||

| 23 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25 | ||||||||||||||||

P < .05 from week 0

Student-Neuman-Kuel’s MRT

Duncan’s MRT

3.3.6. ELISA analysis of IgA antibody response

ELISA data were analyzed to determine the relative magnitude of the IgA antibody responses (Fig. 7 B). In these cases, absorbance values for serum dilutions at 1:200 were used for the same reason that those at 1:1600 were used to analyze the IgG responses. The mean secondary responses peaked at week 5 post-primary injection, similar to that for IgG, but the mean tertiary responses peaked at week 11 after the primary injection, later than the IgG responses.

Comparison of mean absorbance values between pre-immune (week 0) and immune sera at 1:200 showed significant differences by ANOVA at p < 0.05 for SP-10, ESP and SAMP 32 but not for SAMP 14 or SLLP-1. Application of Student-Neuman-Kuel’s and Duncan’s multiple range test (Table 2) showed that there were significant differences between weeks 0 and weeks following the first and second boosters by Duncan’s MRT for SP-10, ESP and SAMP 32. Week 11 showed a significant increase in antibody response to SLLP-1. Only after the second booster were differences significant for SP-10 and ESP using Student-Neuman-Kuel’s MRT.

Table 2.

Mean IgA absorbance values that are significantly different from pre-immune values for each component of the vaccine

| Week | Anti-SP-10 | Anti-ESP | Anti-SAMP-32 | Anti-SAMP-14 | Anti-SLLP-1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

Mean | Standard error |

Statistical test* |

|

| 0 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.018 | |||||||||||

| 1 | 0.053 | 0.009 | 0.060 | 0.025 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 0.062 | 0.009 | 0.053 | 0.018 | |||||||||||

| 3 | 0.059 | 0.017 | 0.052 | 0.016 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 0.355 | 0.34 | b | 0.155 | 0.042 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 0.365 | 0.065 | b | 0.168 | 0.037 | 0.254 | 0.089 | b | |||||||

| 6 | 0.362 | 0.059 | b | 0.199 | 0.026 | b | |||||||||

| 7 | 0.349 | 0.107 | b | 0.126 | 0.036 | ||||||||||

| 8 | 0.421 | 0.075 | b | 0.151 | 0.021 | ||||||||||

| 9 | 0.637 | 0.069 | a b | 0.315 | 0.048 | a b | 0.264 | 0.054 | b | ||||||

| 10 | 0.675 | 0.117 | a b | 0.334 | 0.071 | a b | 0.271 | 0.046 | b | ||||||

| 11 | 0.696 | 0.159 | a b | 0.320 | 0.063 | a b | 0.338 | 0.069 | b | 0.497 | 0.231 | b | |||

| 12 | 0.599 | 0.100 | a b | 0.309 | 0.050 | a b | 0.252 | 0.089 | b | ||||||

| 13 | 0.591 | 0.083 | a b | 0.292 | 0.040 | a b | 0.281 | 0.064 | b | ||||||

| 15 | 0.523 | 0.078 | a b | 0.286 | 0.050 | a b | 0.261 | 0.073 | b | ||||||

| 17 | 0.556 | 0.098 | a b | 0.255 | 0.044 | b | |||||||||

| 19 | 0.495 | 0.108 | a b | 0.167 | 0.020 | ||||||||||

| 21 | 0.518 | 0.128 | b | 0.135 | 0.018 | ||||||||||

| 23 | 0.398 | 0.132 | b | 0.168 | 0.025 | ||||||||||

| 25 | 0.418 | 0.140 | b | 0.146 | 0.037 | ||||||||||

P < .05 from week 0

Student-Neuman-Kuel’s MRT

Duncan’s MRT

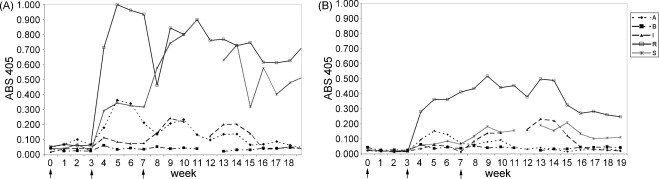

Although the mean absorbance values were rarely significantly different from pre-immune values for SAMP 14 and SLLP-1, monkey R had remarkably high titers to both SLLP-1 and SAMP 14 compared to the other monkeys, as did monkey S to SLLP-1 (Fig. 8A and B).

Figure 8.

ELISA analysis of IgA response to two antigens. (A) Anti–SLLP-1 and (B) anti-SAMP 14 IgA immune absorbance values for each monkey. Monkeys R and S were particularly good responders with anti-SLLP-1-specific IgA, as was monkey R with anti-SAMP 14- specific IgA. Both monkeys also had higher absorbance values for anti-SLLP-1 and anti-SAMP 14 IgG than the other monkeys (data not shown). These data illustrate the variability seen between monkeys to a particular antigen.

3.4. Duration of IgG and IgA antibody response

For purposes of this analysis, the duration of the antibody response was defined as the number of weeks that the absorbance value was significantly increased above pre-immune values by p ≤ .05 after the second booster. Table 3 shows the mean duration of IgG and IgA responses to each antigen. Using Student-Neuman-Keul’s MRTs, the duration of IgG responses to ESP and SAMP 32 was 1 week, 2 weeks to SAMP 14, 3 weeks to SLLP-1, 3 weeks and 4 weeks to SP-10. According to Duncan’s MRT, the duration of IgG responses was twice as long as the more restrictive MRT for SP-10, ESP and SAMP 32. The duration of anti-SLLP-1 and SAMP 14 IgG was one week longer than Student-Neuman-Keul’s MRT.

Table 3.

Mean duration of the antibody responses to each vaccine component after the second booster injection based on the number of weeks that the absorbance values remained significantly greater than pre-immune absorbance values.

| Antibody | IgG duration with significance p < .05 after the second boost | IgA duration with significance p < .05 after the second boost | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-N-K | D | S-N-K | D | |

| Anti-SP-10 | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 8 weeks | 13 weeks |

| Anti-ESP | 1 week | 4 weeks | 6 weeks | 7 weeks |

| Anti-SAMP-32 | 1 week | 4 weeks | 0 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Anti-SAMP 14 | 2 weeks | 3 weeks | 0 weeks | 0 weeks |

| Anti-SLLP-1 | 3 weeks | 4 weeks | 0 weeks | 1 week |

S-N-K: Student-Neuman Kuel Multiple Range Test

D: Duncan Multiple Range Test

When IgA responses were significant by Student-Neuman-Keul’s MRTs, the duration of the response was at least twice as long as the IgG response was to a particular antigen. Duncan’s MRT showed durations of IgA to be 2, 3 and 5 weeks longer than IgG responses to SAMP 32, ESP and SP-10 respectively.

3.5. Analysis of the effect of sera on binding and fusion in HEPT assays

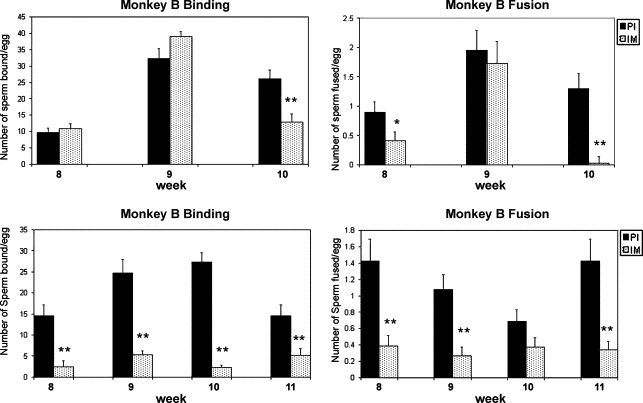

HEPT were performed to determine whether serum antibodies had any functional effects on sperm-egg interactions. Capacitated human spermatozoa were treated with pre-immune or immune serum samples collected at selected weeks following either the first or second booster from each monkey followed by co-incubation with zona-free hamster oocytes (Fig. 9 A and B). Following primary inoculation, treatment of sperm with sera from monkey A showed significant inhibition of binding at week 10 and fusion inhibition at weeks 8 and 10 compared to preimmune serum. Treatment of sperm with sera from monkey B showed significant inhibition of binding at weeks 8, 9, 10 and 11 and fusion inhibition at weeks 8 and 9 compared to pre-immune serum. Sera from other weeks and monkeys did not show either binding or fusion inhibition. No correlation was apparent between absorbance values for individual antigens within each serum sample tested and inhibition of binding or fusion.

Figure 9.

Sperm binding and fusion in the hamster egg penetration test in which capacitated human sperm, pre-incubated with a 1:10 dilution of pre-immune and or immune sera against the multicomponent vaccine, were co-incubated with zona-free hamsters eggs. Following primary inoculation, treatment of sperm with sera from monkey A showed significant inhibition of binding at week 10 and fusion inhibition at weeks 8 and 10 compared to pre-immune serum. Treatment of sperm with sera from monkey B showed significant inhibition of binding at weeks 8, 9, 10 and 11, and fusion inhibition at weeks 8, 9 and 11 compared to preimmune serum. Bars represent ± the standard error of 3 to 5 individual experiments. * p< .05; ** p< .01.

4. Discussion

This study provides evidence that antibodies can be raised to individual components of a multi-component acrosomal protein vaccine formulation in a primate model whose reproductive tract functions and cyclicity closely resembles women. Furthermore, the recombinant human sperm proteins used in this formulation induce an immune response that recognizes the endogenous proteins in both human and monkey sperm, ultimately enabling us to use monkeys in a pre-clinical fertility trial without the need to subsequently reformulate a vaccine for clinical testing. Both peripheral (IgG) and mucosal (IgA) responses to each component immunogen were detected following an intramuscular route of inoculation with a mild adjuvant, aluminum hydroxide, approved for human use.

Immunization of female monkeys with a mixture of five human recombinant acrosomal antigens adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide elicited a variable humoral immune response to each protein between monkeys, as was expected in an outbred population of primates. The variability of the response lends credence to the use of a multicomponent contraceptive vaccine in humans whose immune systems vary substantially due to factors such nutritional and disease status as well as genetics. There are several other factors that may have contributed to the variable magnitude of response to each antigen within each monkey including: 1) the size of each recombinant protein; 2) physical or chemical interactions between proteins; 3) incomplete absorbance of one or more proteins to the aluminum hydroxide adjuvant; and 4) solubility/stability problems due to salt concentrations and/or pH of the vaccine vehicle (Insel, 1995). A greater antibody response to the larger proteins might occur because of the presentation of a greater number of epitopes. Indeed, the highest mean IgG antibody absorbance values were to the largest of the five proteins, SP-10, ESP and SAMP 32. However, the highest mean IgA absorbance values included not only SP-10 at ~ 45kDa, but also SLLP-1 at ~15kDa. Although epitope mapping has not been done with any of the recombinant proteins, it is possible that overall size alone is not as important as the number or size of epitopes available to antigen presenting cells (APC). Considering the duration of the responses, the mean IgG and IgA response to SP-10, the largest of the recombinant proteins, persists longer than all other responses.

The presence of a systemic immune response does not preclude a mucosal immune respopnse. The presence of antigen-specific serum IgA antibodies in this study suggests that a mucosal immune response has also been induced although there are more efficient routes of vaccine inoculation to induce, a mucosal response (Brandtzaeg et al., 1998; Anderson, 2003). Indirect support for the presence of a mucosal response comes from our study using cynomolgus monkeys immunized with SP-10 (Kurth et al., 1997a, 1997b). We found SP-10-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in sera as well as oviductal fluid (OF), and the apparent concentration of IgA in the OF indicated that there was local production of IgA antibody even though the immunogen was delivered via intramuscular injection.

Lowe et. al. (1997) have found also that monkeys, immunized intramuscularly with virus-like particles (VLPs) against human papillomavirus type II using aluminum hydroxyphosphate as the adjuvant, mounted high titers of specific IgG antibodies which were found in both serum and cervicovaginal secretions. These studies suggest that antibodies found in the female reproductive tract after systemic immunization may be locally secreted as well as serum transudate. In either case, as long as there are high titers of vaccine-specific antibodies in the reproductive tract, there is the potential for an effective contraceptive vaccine. An advantage to using sperm proteins exposed in the oviduct immediately prior to fertilization is that the number of sperm that antibodies (thus lower titers) would need to bind is miniscule compared to the millions of sperm found in the vagina following intercourse.

Although antibodies were raised to all five sperm antigens, only a few of the sera used in HEPT showed significant effects on sperm-egg interactions. In addition, no sera showed significant effects in agglutination assays (data not shown). These observations suggest that the vaccine formulation might benefit from the addition of more sperm-surface specific recombinant proteins.

We are currently analyzing oviductal fluid and cervical mucus of these same monkeys for the presence of specific antibodies to each of the five recombinant proteins in the vaccine. Those data will enhance our understanding of what is necessary to induce an effective antibody response in the female reproductive tract and the effect of systemic immunization on genital tract immunity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Donna Mathis for an enormous amount of help in collecting monkey fluids. This research was supported by U54 NIH grant # HD29099.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson AO. Peripheral and Mucosal Immunity: Critical Issues for Oral Vaccine Design. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Bedford JM, Moore HD, Franklin LE. Significance of the equatorial segment of the acrosome of the spermatozoon in eutherian mammals. Exp. Cell. Res. 1979;119:119–126. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(79)90341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtzaeg P, Farstad IN, Haraldsen G, Jahnsen FL. Cellular and molecular mechanisms for induction of mucosal immunity. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1998;92:93–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coonrod SA, Herr JC, Westhusin ME. Inhibition of bovine fertilization in vitro by antibodies to SP-10. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1996;107:287–297. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1070287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JA, Herr JC. Interactions of human sperm acrosomal protein SP-10 with the acrosomal membranes. Biol. Reprod. 1992;46:981–990. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod46.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JA, Klotz KL, Flickinger CJ, Thomas TS, Wright RM, Castillo JR, Herr JC. Human SP-10: acrosomal distribution, processing, and fate after the acrosome reaction. Biol. Reprod. 1994;51:1222–1231. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.6.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg E, Wheat TE, Powell JE, Stevens VC. Reduction of fertility in female baboons immunized with lactate dehydrogenase C4. Fertil. Steril. 1981;35:214–217. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)45325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin PD. Immunization against HCG. Hum. Reprod. 1994;9:267–272. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Relyveld EH, Lindblad EB, Bizzini B, Ben-Efraim S, Gupta CK. Adjuvants - a balance between toxicity and adjuvanticity. Vaccine. 1993;11:293–306. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Z, Wolkowicz MJ, Shetty J, Klotz K, Bolling L, Sen B, Westbrook VA, Coonrod S, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. SAMP32, a testis-specific, isoantigenic sperm acrosomal membrane-associated protein. Biol. Reprod. 2002;66:735–744. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr JC, Flickinger CJ, Homyk M, Klotz K, John E. Biochemical and morphological characterization of the intra-acrosomal antigen SP-10 from human sperm. Biol. Reprod. 1990a;42:181–193. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr JC, Wright RM, John E, Foster J, Kays T, Flickinger CJ. Identification of human acrosomal antigen SP-10 in primates and pigs. Biol. Reprod. 1990b;42:377–382. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod42.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue N, Ikawa M, Isotani A, Okabe M. The immunoglobulin superfamily protein Izumo is required for sperm to fuse with eggs.[see comment] Nature. 2005;434:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel RA. Potential alterations in immunogenicity by combining or simultaneously administering vaccine components. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1995;754:35–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb44436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, Bassham B, Lipshultz LI, Lamb DJ. Handbook of the Laboratory Diagnosis and Treatment of Infertility. Boston: CRC Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jones WR, Bradley J, Judd SJ, Denholm EH, Ing RM, Mueller UW, Powell J, Griffin PD, Stevens VC. Phase I clinical trial of a World Health Organisation birth control vaccine. Lancet. 1988;1:1295–1298. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth BE, Bryant D, Naaby-Hansen S, Reddi PP, Weston C, Foley P, Bhattacharya R, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. Immunological response in the primate oviduct to a defined recombinant sperm immunogen. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1997a;35:135–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(97)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth BE, Klotz K, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. Localization of sperm antigen SP-10 during the six stages of the cycle of the seminiferous epithelium in man. Biol. Reprod. 1991;44:814–821. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth BE, Weston C, Reddi PP, Bryant D, Bhattacharya R, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. Oviductal antibody response to a defined recombinant sperm antigen in macques. Biol. Reprod. 1997b;57:981–989. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe RS, Brown DR, Bryan JT, Cook JC, George HA, Hofmann KJ, Hurni WM, Joyce JG, Lehman ED, Markus HZ, Neeper MP, Schultz LD, Shaw AR, Jansen KU. Human papillomavirus type 11 (HPV-11) neutralizing antibodies in the serum and genital mucosal secretions of African green monkeys immunized with HPV-11 virus-like particles expressed in yeast. J. Infect. Dis. 1997;176:1141–1145. doi: 10.1086/514105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy DW. Vaccine Adjuvants. Seminars in Veterinary Medicine and Surgery (Small Animals) 1997;12:206–211. doi: 10.1016/s1096-2867(97)80034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal A, Klotz KL, Shetty J, Jayes FL, Wolkowicz MJ, Bolling LC, Coonrod SA, Black MB, Diekman AB, Haystead TA, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. SLLP1, a unique, intra-acrosomal, non-bacteriolytic, c lysozyme-like protein of human spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 2003;68:1525–1537. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.010108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hern PA, Bambra CS, Isahakia M, Goldberg E. Reversible contraception in female baboons immunized with a synthetic epitope of sperm-specific lactate dehydrogenase. Biol. Reprod. 1995;52:331–339. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hern PA, Liang ZG, Bambra CS, Goldberg E. Colinear synthesis of an antigen-specific B-cell epitope with a 'promiscuous' tetanus toxin T-cell epitope: a synthetic peptide immunocontraceptive. Vaccine. 1997;15:1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson M, Wilson MR, Jennings ZA, van Duin M, Aitken RJ. Design and evaluation of a ZP3 peptide vaccine in a homologous primate model. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1999;5:342–352. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddi PP, Castillo JR, Klotz K, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. Production in Escherichia coli, purification and immunogenicity of acrosomal protein SP-10, a candidate contraceptive vaccine. Gene. 1994;147:189–195. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibner V. Adverse Effects of Adjuvants in Vaccines. Nexus. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Shetty J, Wolkowicz MJ, Digilio LC, Klotz KL, Jayes FL, Diekman AB, Westbrook VA, Farris EM, Hao Z, Coonrod SA, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. SAMP14, a novel, acrosomal membrane-associated, glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored member of the Ly-6/urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor superfamily with a role in sperm-egg interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30506–30515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevchenko A. silver staining of polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, O'Hagan D. Advances in vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999;17:1075–1081. doi: 10.1038/15058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens VC. Progress in the development of human chorionic gonadotropin antifertility vaccines. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1996;35:148–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1996.tb00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talwar GP, Hingorani V, Kumar S, Roy S, Banerjee A, Shahani SM, Krishna U, Dhall K, Sawhney H, Sharma NC, et al. Phase I clinical trials with three formulations of antihuman chorionic gonadotropin vaccine. Contraception. 1990;41:301–316. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(90)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thau RB, Sundaram K. The mechanism of action of an antifertility vaccine in the rhesus monkey: reversal of the effects of antisera to the beta-subunit of ovine luteinizing hormone by medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil. Steril. 1980;33:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)44601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassarman PM. Towards a molecular mechanism for gamete adhesion and fusion during mammalian fertilization. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1995;7:658–664. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkowicz MJ, Coonrod SA, Reddi PP, Millan JL, Hofmann MC, Herr JC, Coonrod SM. Refinement of the differentiated phenotype of the spermatogenic cell line GC-2spd(ts) Biol. Reprod. 1996;55:923–932. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkowicz MJ, Shetty J, Westbrook A, Klotz K, Jayes F, Mandal A, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. Equatorial segment protein defines a discrete acrosomal subcompartment persisting throughout acrosomal biogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 2003;69:735–745. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R. Mammalian Fertilization. In: Knobil E, Neill JD, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 189–317. [Google Scholar]