Abstract

We identified an antigen recognized on a human non-small-cell lung carcinoma by a cytotoxic T lymphocyte clone derived from autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. The antigenic peptide is presented by HLA-A2 and is encoded by the CALCA gene, which codes for calcitonin and for the α-calcitonin gene-related peptide. The peptide is derived from the carboxy-terminal region of the preprocalcitonin signal peptide and is processed independently of proteasomes and the transporter associated with antigen processing. Processing occurs within the endoplasmic reticulum of all tumoral and normal cells tested, including dendritic cells, and it involves signal peptidase and the aspartic protease, signal peptide peptidase. The CALCA gene is overexpressed in medullary thyroid carcinomas and in several lung carcinomas compared with normal tissues, leading to recognition by the T cell clone. This new epitope is, therefore, a promising candidate for cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: antigen processing, signal peptidase, signal peptide peptidase

The analysis of tumor-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) derived from patients with various solid tumors had led to promising new treatments for malignant diseases, by either expanding the T cells in vitro before transferring them with IL-2 into patients (1) or identifying their target antigens (Ags), which can then be used in therapeutic vaccines. A large number of tumor-associated Ags recognized by CTLs has been identified mainly in malignant melanoma. Unfortunately, clinical studies indicate that, despite an increase in the frequency of antitumor CD8 T cells, the efficacy of current therapeutic vaccines remains limited (2). Current studies are focusing on a better understanding of the mechanisms of rare tumor regressions observed (3, 4), the activation state of anti-vaccine CD8 T cells, and their capacity to migrate to the tumor site.

Much less is known about the antigenicity and susceptibility to CTL attack of human lung tumors. Most of these tumors are non-small-cell lung carcinomas (NSCLCs), a large group that includes squamous-cell, adeno-cell, and large-cell (LCC) carcinomas. NSCLCs can be infiltrated by T cell antigen receptor (TCR) α/β T cells (5). The identified T cell target Ags include peptides encoded by the HER2/neu protooncogene (6), which is overexpressed in many lung tumors, and by several genes that were found to contain a point mutation in tumor cells compared with autologous normal cells. These mutated genes include elongation factor 2 (7), malic enzyme (8), α-actinin-4 (9), and NFYC (10). In addition, several cancer/germ-line genes are expressed in NSCLCs (11, 12), which should lead to the presence of tumor-specific Ags at the surface of cancer cells. However, spontaneous T cell responses against MAGE-type Ags have not been observed in lung cancer patients thus far. Therefore, identification of new lung cancer Ags, in particular those shared by tumors of several patients, would help the design and immunological monitoring of vaccination strategies in lung cancer.

Most antigenic peptides recognized by CD8 T cells originate from degradation in proteasomes of intracellular mature proteins and their transport, by the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) from the cytosol into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (for review, see ref. 13). The resulting peptides of 9 to 10 amino acids bind MHC class I (MHC-I) molecules and are then conveyed to the cell surface. An increasing number of epitopes recognized by tumor-reactive T cells has been reported to result from nonclassical mechanisms acting at the transcription, splicing, or translational levels (for review, see ref. 14). It is noteworthy that several tumor epitopes are poorly processed by dendritic cells (DCs), which are unique in their capacity to process Ags and to prime CD8 T cells, but which constitutively express immunoproteasomes (15, 16). In this article, we identified an antigenic peptide recognized on a human LCC by an autologous CTL clone. This epitope is derived from the carboxy (C)-terminal region of the calcitonin (CT) precursor signal sequence and is processed by a proteasome-independent pathway involving signal peptidase (SP) and signal peptide peptidase (SPP).

Results

A CTL Clone Recognizing Autologous Lung Carcinoma Cells.

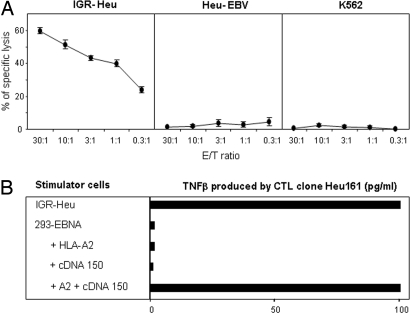

Patient Heu is a now disease-free lung cancer patient 12 years after resection of the primary tumor. LCC cell line IGR-Heu was derived from a tumor resected from the patient in 1996. Mononuclear cells infiltrating the primary tumor were isolated and stimulated with irradiated IGR-Heu tumor cells, irradiated autologous EBV-transformed B cells, and IL-2. Responder lymphocytes were cloned by limiting dilution. Several tumor-specific CTL clones were obtained and classified into three groups on the basis of their TCRVβ usage (5). We previously reported that the first two groups of clones recognized an antigenic peptide encoded by a mutated α-actinin-4 gene (9, 17). Here, we analyze the third group of clones, including Heu161, which expresses a Vβ3-Jβ1.2 TCR. CTL Heu161 lysed the autologous tumor cell line, but not autologous EBV-B cells or the NK-target K562 (Fig. 1A). The recognition of IGR-Heu by the CTL clone was inhibited by anti-HLA-A2 mAb (9).

Fig. 1.

CTL clone Heu161 recognizes an Ag expressed by IGR-Heu autologous tumor cells. (A) Cytotoxic activity of CTL Heu161 toward tumor cells IGR-Heu, autologous Heu-EBV B cells, and K562. Cytotoxicity was measured by 51Cr-release assay at indicated E/T ratios. (B) Identification of a cDNA clone encoding the Ag recognized by the CTL clone. Heu161 (3,000 cells) was stimulated for 24 h by 293-EBNA (30,000 cells) cotransfected with vectors pCEP4 containing cDNA clone 150 and pcDNA3.1 containing HLA-A2. Control stimulator cells included IGR-Heu and 293-EBNA transfected with cDNA 150 or HLA-A2 alone. The concentration of TNFβ released in medium was measured. Data are representative of five independent experiments.

Identification of the Gene Encoding the Ag Recognized by Heu161 CTL.

A cDNA library from IGR-Heu cells was cloned into expression plasmid pCEP4 (9) and divided into 264 pools of ≈100 recombinant clones. DNA prepared from each pool was transfected into 293-EBNA cells, together with an HLA-A*0201 construct. CTL Heu161 was added to the transfectants, and then TNFβ was measured. A large proportion (85 of 264) of cDNA pools proved positive, suggesting that a surprisingly high frequency of ≈0.4% of cDNA clones encoded the Ag. One pool of cDNA was subcloned, and a cDNA clone named 150 was isolated (Fig. 1B).

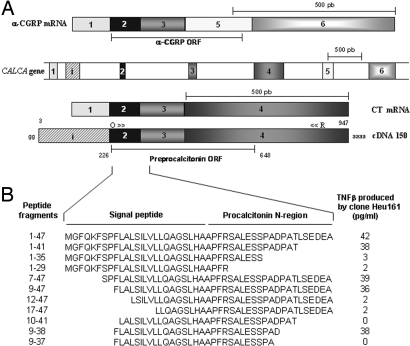

cDNA 150 was 956 bp long and contained a polyadenylation signal and a poly(A) tail. Its sequence corresponded to that of gene CALCA, which codes for both the calcium-lowering hormone CT and the CT gene-related peptide α (α-CGRP). A primary transcript is spliced into either CT or α-CGRP mRNA through tissue-specific alternative RNA processing (18). cDNA 150 contains the complete CT coding sequence, spanning exons 2, 3, and 4 of gene CALCA (Fig. 2A). However, its 5′ end differs from that of the CT cDNA sequences present in databanks by the presence of an intronic sequence of 213 nucleotides.

Fig. 2.

Identification of the gene segment encoding the epitope recognized by Heu161 CTL. (A) Representation of cDNA 150 compared to the CT and α-CGRP gene and transcripts. Numbered boxes represent exons. Arrows indicate forward (O) and reverse (R) primers used in RT-PCR. (B) Minigenes used to identify the region coding for the antigenic peptide. A series of truncated constructs were cotransfected into 293-EBNA cells with HLA-A2. The corresponding encoded sequences are shown. Recognition by Heu161 was assessed by using TNFβ assay as in Fig. 1B. Statistical analyses were performed by using a Mann–Whitney U test (P < 0.01). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Identification of the Antigenic Peptide.

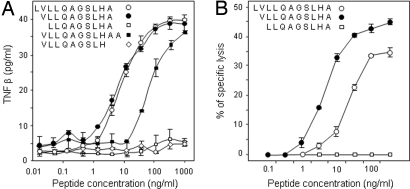

The region coding for the antigenic peptide was identified with truncated cDNA fragments cloned into expression plasmids and cotransfected with the HLA-A2 construct into 293-EBNA cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, a fragment encoding the first 41 residues of preproCT (ppCT) transferred the expression of the Ag, whereas a fragment encoding the first 35 residues did not. We then prepared a series of CT cDNA fragments truncated at their 5′ end and engineered to contain an initiation codon and a Kozak consensus sequence. Screening with the CTL clone indicated that the antigenic peptide was contained within residues 9–47 (Fig. 2B). Further trimming narrowed down the peptide-encoding region to residues 9–38 (Fig. 2B). Among a set of overlapping peptides covering this region, two were recognized by clone Heu161, VLLQAGSLHA and LVLLQAGSLHA, which are identical, but with an additional Leu in the latter peptide. As shown in Fig. 3A, both peptides sensitized HLA-A2 melanoma cells to recognition by Heu161, with half-maximal effects obtained with ≈10 nM of peptide. In a lysis assay, the decamer was slightly more efficient than the 11-mer by a factor of ≈3 (Fig. 3B). We concluded that the optimal peptide recognized by Heu161 was VLLQAGSLHA or ppCT16–25. It contains one of the consensus HLA-A2 peptide-binding motifs, Leu, Ile, or Met in position 2, but fails to contain the peptide-binding motif, Leu or Val in position 10, and has therefore a moderate ability to bind to HLA-A2 (data not shown). This peptide corresponds exactly to the C-terminal part of the ppCT signal peptide (19).

Fig. 3.

Identification of the peptide recognized by clone Heu161. (A) CTL stimulation with purified synthetic peptides. Peptides were loaded on allogeneic HLA-A2 MZ2-MEL.3.1 melanoma cells for 1 h at room temperature before addition of Heu161 at 1/10 E/T ratio. TNFβ release was measured 24 h later. (B) Cytotoxicity of Heu161 toward peptide-pulsed cells. 51Cr-labeled Heu-EBV B cells were incubated over 1 h with the indicated concentrations of peptides before addition of CTL at 10:1 E/T ratio. Data are representative of four independent experiments.

Processing of the Antigenic Peptide.

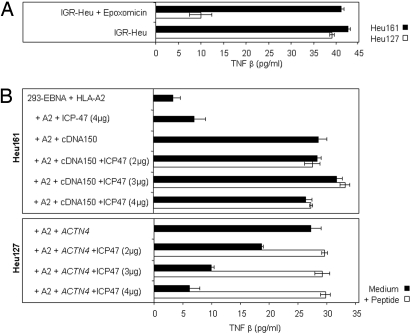

This localization of the peptide in the protein suggested that it could be processed in the ER independently of proteasomes and TAP. To examine the involvement of proteasomes, IGR-Heu cells were treated with specific proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (Fig. 4A). Epoxomicin had no effect on recognition by anti-ppCT CTL (Fig. 4A). In contrast, it strongly inhibited stimulation of another autologous CTL clone, Heu127, which recognizes a mutated α-actinin-4 peptide (9). This finding was expected because α-actinin-4 is a cytosolic protein that is degraded, at least in part, in proteasomes (20). These results suggest that the processing of the ppCT16–25 peptide does not require proteasomal activity. The involvement of TAP was tested by cotransfecting into 293-EBNA cells constructs coding for the antigenic peptide, HLA-A2, and the immediate-early protein ICP47 of herpes simplex virus type 1, which binds to and inhibits human TAP (21). As shown in Fig. 4B, cotransfecting ICP47 had no detectable effect on recognition of the transfectants by anti-ppCT CTL, whereas it strongly inhibited that by the anti-α-actinin-4 CTL. These results strongly suggest that the processing of the ppCT16–25 epitope is TAP-independent.

Fig. 4.

Processing of the ppCT16–25 peptide is proteasome- and TAP-independent. (A) IGR-Heu cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (10 μM), and then Heu161 cells were added at 1/10 E/T ratio. The autologous Heu127 clone was included as a positive control. TNFβ released in medium after 24 h of culture was measured. (B) 293-EBNA cells were cotransfected with pCEP4 containing either cDNA 150 (Upper) or the mutated α-actinin-4 cDNA (Lower), with HLA-A2 construct, and with various amounts of vector pBJi-neo containing IPC47 cDNA. Heu161 (Upper) or Heu127 (Lower) were then added at 1/10 E/T ratio. TNFβ released after 24 h of culture was measured. Controls included 293-EBNA cells transfected with HLA-A2 or pBJi-neo-IPC47 alone and incubation of transfectants with either ppCT or α-actinin-4 peptides. Data correspond to one of four independent experiments.

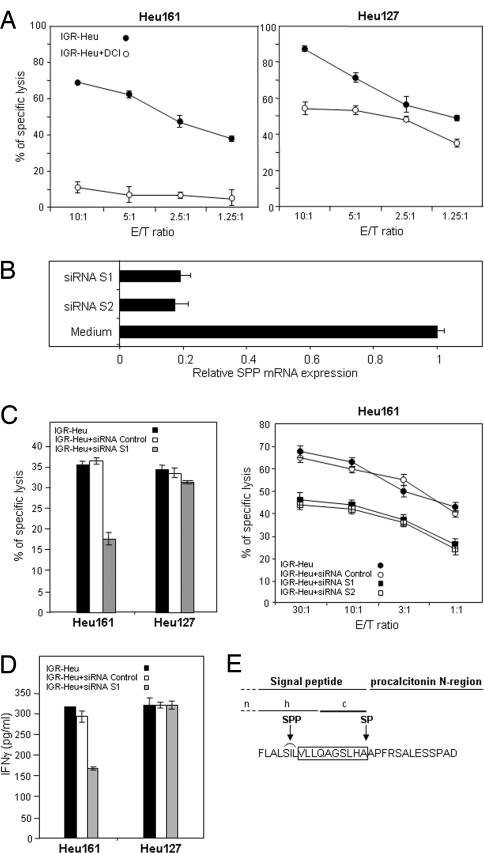

Because the C terminus of antigenic peptide VLLQAGSLHA corresponded to the C terminus of the ppCT signal sequence (19), it was expected to be generated by type I SP, which cuts off signal peptides from secretory proteins on the luminal side of the ER membrane (22). SP involvement was tested by using the serine protease inhibitor dichloroisocoumarin (DCI) (23). Remarkably, preincubation of IGR-Heu cells with DCI rendered them resistant to lysis by the anti-ppCT CTL (Fig. 5A). The same treatment had only a moderate effect on recognition by the Heu127 clone (Fig. 5A), and this outcome probably resulted from a slight decrease in MHC-I expression on DCI-treated tumor cells (data not shown). These results are compatible with involvement of SP in processing the ppCT16–25 peptide. After cleavage by SP, some of the signal sequences inserted in the ER membrane in a type II or loop-like orientation can be further cleaved by the intramembrane protease SPP (reviewed in ref. 24). We therefore specifically knock down SPP expression in IGR-Heu with two distinct siRNA. siRNA-S1 and siRNA-S2 specifically inhibit SPP expression at both RNA (Fig. 5B) and protein (data not shown) levels. The down-regulation of SPP resulted in a strong decrease in the sensitivity of the tumor cells to lysis by the anti-ppCT, but not by the anti-α-actinin-4 CTL (Fig. 5C). Similar inhibition was observed when tumor cells were used to stimulate production of IFNγ by CTL (Fig. 5D). Partial inhibition of Heu161 reactivity correlates with partial inhibition of SPP protein expression in siRNA-treated IGR-Heu cells. This finding may be due to the relative stability of SPP homodimers in ER membrane (25). Together, these results indicate that the ppCT16–25 peptide was most likely processed by SP and SPP within the ER (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5.

Processing of the ppCT16–25 epitope involves SP and SPP. (A) Processing of the ppCT16–25 epitope is SP-dependent. IGR-Heu cells were incubated with the SP inhibitor DCI (250 μM) before addition of anti-ppCT (Left) or anti-α-actinin-4 (Right) CTL. (B) Processing of the ppCT16–25 epitope involves SPP. Analysis of SPP mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR analysis. Total RNA extracted from IGR-Heu, electroporated or not with siRNA targeting SPP (siRNA-S1 and siRNA-S2), was reverse-transcribed and quantified by TaqMan. (C) Effect of SPP knockdown on tumor cell recognition. (Left) Lytic activity of Heu161 and Heu127 against IGR-Heu, electroporated or not with siRNA-S1 or control siRNA, determined by 51Cr-release assay at 10/1 E/T ratio. (Right) Cytotoxicity of Heu161 against IGR-Heu, electroporated or not with siRNA-S1, siRNA-S2, or control siRNA, determined by 51Cr-release assay at indicated E/T ratios. (D) Production of IFNγ by Heu161 and Heu127 clones stimulated with tumor cells electroporated or not with siRNA-S1 or control siRNA. (E) The ppCT16–25 peptide is located at the C terminus of the signal sequence of the CT hormone precursor. The optimal peptide recognized by Heu161 is boxed. Arrows indicate the SP and the approximate SPP cleavage sites. The n, h, and c regions in the ppCT signal peptide were predicted by using SignalP 3.0 software. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Expression of the CT Gene Product in Tumor Samples.

Expression of the CT transcript was tested in a panel of lung carcinoma samples and cell lines by RT-PCR. Twenty-seven of 209 tumor samples and 5 of 38 cell lines were positive (Table 1). Quantitative gene expression analysis of the CT transcript was then carried out on some of the positive samples (Table 2). Levels of CT gene expression in the three cell lines tested, namely, LCC IGR-Heu, SCLC DMS53, and medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) TT, were at least 100-fold higher than those found in normal human thyroid. It is noteworthy that the level of expression observed in the lung carcinoma cell lines was similar to that observed in the MTC cell line (Table 2). High levels of expression of the CT transcript also were detected in the tumor of patient Heu (Heu-T) and in several lung cancer samples (Table 2).

Table 1.

Expression of the CT transcript in lung tumors

| Variable | Tumor samples | Tumor cell lines |

|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | ||

| SCC | 7/122 | 0/3 |

| ADC | 10/61 | 0/7 |

| LCC | 2/8 | 1/5 |

| Undifferentiated carcinomas | 1/3 | — |

| SCLC | 3/5 | 4/23 |

| Neuroendocrine tumors | 3/6 | — |

| Bronchioalveolar tumors | 1/4 | — |

CT gene expression was tested by RT-PCR.

Table 2.

Relative expression of CT transcript in tumor cell lines and samples

| Variable | Histological type | Relative expression of CT transcript |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor cell lines | ||

| IGR-Heu | LCC | 191.34 |

| DMS53 | SCLC | 116.97 |

| TT | MTC | 259.57 |

| Tumor samples | ||

| NSCLC | ||

| 1 (Heu-T) | LCC | 14.93 |

| 2 | LCC | 0.02 |

| 3 | SCC | 0.28 |

| 4 | SCC | 0.82 |

| 5 | SCC | 0.11 |

| 6 | SCC | 0.17 |

| 7 | SCC | 0.02 |

| 8 | ADC | 19.43 |

| 9 | ADC | 4.86 |

| 10 | ADC | 0.02 |

| 11 | ADC | 0.00 |

| 12 | ADC | 12.82 |

| 13 | ADC | 9.92 |

| 14 | ADC | 29.65 |

| 15 | ADC | 1.00 |

| 16 | ADC | 7.26 |

| 17 | Undifferentiated | 7.57 |

| 18 | Undifferentiated | 13.64 |

| SCLC | ||

| 19 | SCLC | 0.14 |

| 20 | Neuroendocrine | 2.27 |

| 22 | Neuroendocrine | 0.74 |

| 23 | Bronchioalveolar | 0.02 |

| Normal tissues | ||

| Pool of human lung | Lung | 0.00 |

| Pool of human thyroid | Thyroid | 1.15 |

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of CT transcript in tumor cell lines and samples. Normalized copy numbers of CT transcript are shown. The values of CT transcript that are statistically elevated were shown in bold (P < 0.0001 according to Mann–Whitney U test).

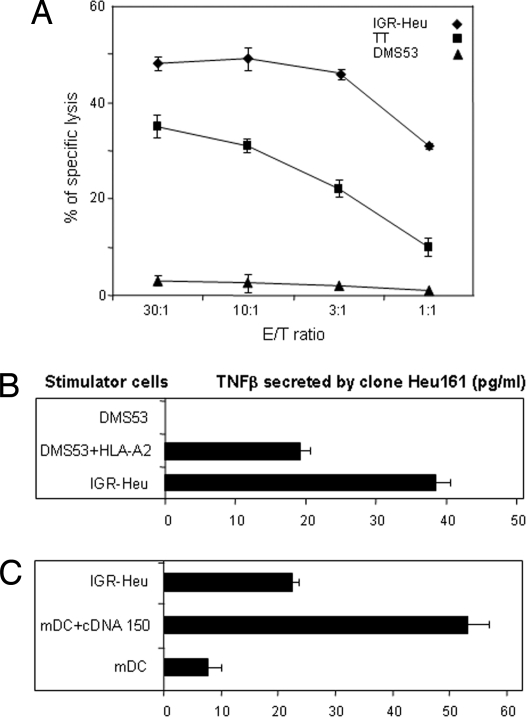

Next, we tested whether CTL Heu161 also could recognize other HLA-A2 cells that overexpressed the CT gene. As shown in Fig. 6A, Heu161 efficiently lysed MTC cells TT. As expected, Heu161 did not lyse HLA-A2− DMS53 cells, but did recognize these cells after transfection with an HLA-A2 construct (Fig. 6B). Finally, mature DCs derived from blood monocytes of a healthy HLA-A2 donor and transfected with the CT cDNA strongly activated Heu161 CTL (Fig. 6C). We conclude that processing of the peptide ppCT16–25 occurs in all cells tested, namely, NSCLC, SCLC, MTC, melanoma, 293 embryonic kidney cells, and DCs. Therefore, it would appear that all cells expressing the CT transcript at high levels can be recognized by the CTL clone described here.

Fig. 6.

Recognition of allogeneic cells overexpressing CT by Heu161 CTL. (A) Cytotoxicity of CTL Heu161 against allogeneic MTC (TT) and SCLC (DMS53) cell lines. IGR-Heu cells were included as control. (B) Recognition of HLA-A2-transfected DMS53 by Heu161. DMS53 cells were transfected with HLA-A2 before addition of CTL clone at 1/10 E/T ratio. (C) Recognition of mature DC expressing CT. Monocytes were isolated from the blood of an HLA-A2 healthy donor by using magnetic beads and cultured for 6 days in the presence of 100 ng/ml rIL-4 and 250 ng/ml GM-CSF. After maturation by adding 20 ng/ml TNFα for another 3 days, the DC (30,000 cells per well) were transfected with cDNA clone 150 in pCEP4, and the amount of TNFβ released by Heu161 (3,000 cells per well) was measured 24 h later. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

CT and α-CGRP polypeptides are encoded by the same gene, CALCA, which includes five introns and six exons (26). Exons 1, 2, 3, and 4 are joined to produce the CT mRNA in thyroid C cells, whereas exons 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 form the α-CGRP mRNA in neuronal cells (27). Mature α-CGRP is an endogenous vasodilatory peptide widely distributed in the body. CT is a hormone primarily involved in protecting the skeleton during periods of “calcium stress” (28, 29). In humans, it is synthesized as a ppCT, which includes a signal sequence of 25 amino acids, and proCT, comprising an N-terminal region, CT (32 amino acids), and a C-terminal peptide (26). CT was known to be produced at high levels by MTC and, more surprisingly, by some lung carcinomas (30, 31). Here, we confirmed, by using quantitative RT-PCR, that gene CALCA was expressed at high levels in several NSCLC and SCLC. It is noteworthy that CT and α-CGRP preprohormones share their 75 N-terminal residues encoded by CALCA exons 2 and 3 and that the peptide ppCT16–25 is also the ppα-CGRP16–25 peptide. It is therefore likely that cells expressing the α-CGRP, but not the CT transcripts, also can be recognized by CTL such as Heu161.

We have shown here that the signal sequence of the CT and α-CGRP preprohormones contains an antigenic peptide that can be specifically recognized by CTL on lung or MTC cells expressing the gene CALCA. Induction of CALCA gene expression in other cell types, such as 293 or DC, also results in CTL recognition. On the basis of the expression profile of its encoding gene, the ppCT peptide is a neuroendocrine differentiation Ag. Several tissue differentiation Ags have been found to be recognized by tumor-specific CTL on melanomas. They are encoded by genes with melanocyte-specific expression, such as tyrosinase, Melan-AMART1, Pmel17/gp100, TRP-1, and TRP-2. Other examples include gene PSA in prostate and CEA in gut carcinomas. The ppCT16–25 peptide is the first differentiation Ag recognized by CTL in lung cancer, and it is a promising candidate for immunotherapy. Patient Heu mounted a spontaneous CTL response to this Ag without clinical autoimmunity. Whether this remains true with very immunogenic vaccination modalities or adoptive transfer of a high number of specific T cells warrants careful examination. Relevant information may come from vaccination studies against MTC carried out with the CT polypeptide (32).

It is possible that gene CALCA is overexpressed in some neuroendocrine tumors compared with normal thyroid C cells, which would increase the tumoral selectivity of CTL such as Heu161. Our observation by using quantitative RT-PCR that tumor cell lines express 100- to 200-fold higher levels of CALCA transcripts than normal thyroid tissue, which can be estimated to contain ≈1% of CT-producing C cells, does not support the concept of overexpression in tumoral versus normal cells. However, during the screening of the tumor cDNA library, we were surprised by the high proportion of CT transcripts. Along the same line, during our transfection experiments with cDNA clone 150, we observed that a high level of gene expression was required for recognition by Heu161. At this stage, and also considering the unusual mechanism of processing of the antigenic peptide the efficiency of which could be low, we favor the hypothesis that high levels of CALCA gene expression are indeed required for recognition by anti-ppCT16–25 CTL, but that such levels also might be present in some normal cells.

Another interesting aspect of the ppCT16–25 epitope lies in its processing. Like that of other proteins, the leader sequence of ppCT is markedly hydrophobic. It mediates binding of the protein to the membrane of the ER, where nascent polypeptide precursors are processed (for review, see ref. 33). It is then immediately cleaved by SP (22) at the Ala25–Ala26 site (19). ppCT16–25 peptide is at the C terminus of the leader sequence. Several results point to involvement of SP in its processing: (i) the exact match between the SP cleavage site and the peptide C terminus (Fig. 3A), (ii) the processing that is independent of proteasomes and TAP (Fig. 4 A and B) and that therefore presumably occurs in the ER, and (iii) the effect of DCI, which is known to inhibit SP (Fig. 5A). That SP generates the C terminus of the antigenic peptide probably explains why minigenes coding for peptides shorter than 9–38 did not confer antigenicity, although the antigenic peptide was much smaller (Fig. 2). We have probably defined the sequence that is necessary and sufficient to provide the conformation required for SP activity. Although it is well known from peptide elution experiments that MHC-I molecules can be loaded with peptides derived from leader sequences (34, 35) and that some of these peptides can be targeted by CTL (36, 37), little is known about the exact mechanisms of processing of these antigenic peptides. Our results are evidence for direct involvement of SP in this processing.

After release from precursor proteins by cleavage with SP, some signal peptides with a type II orientation (i.e., those spanning the ER membrane with the n region exposed toward the cytosol and the c region facing the ER lumen) (24) can undergo intramembrane proteolysis and be cleaved in the center of their h region by the presenilin-type aspartic protease SPP (38). Thereby, SPP promotes the release of signal peptide fragments from the ER membrane. After cleavage by SPP, signal peptide fragments can be released into either the cytoplasm, to be processed by the proteasome/TAP pathway, or the ER, where they follow TAP-independent processing (24). The substrate spectrum of SPP is thus far limited to a variety of viral proteins, such as hepatitis C virus (39) and GB virus (40), and signal peptides, such as preprolactin (41) and human MHC-I (42). Our results strongly suggest that the ppCT signal peptide is another substrate of SPP and that this protease directly processes the ppCT16–25 CTL epitope.

Thus far, the only known peptides loaded on HLA molecules after processing by SPP are derived from MHC-I. Peptides processed by SPP from the N-terminal portion of the signal sequences of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C can be loaded onto nonclassical HLA-E molecules (42). This loading is required for HLA-E transfer to the cell surface, where these molecules can bind the NK inhibitory receptors CD94/NKG2 and block NK activity (43). It was shown that HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C peptides were released into the cytosol and required further processing by proteasomes and transfer into the ER through TAP before HLA-E loading (44). The CTL epitope identified in the present study derives from the C terminus of the ppCT signal sequence (Fig. 5E). Therefore, it is probably released directly into the ER and thus does not require proteasomes and TAP for its processing. The proteasome/TAP-independent Ag processing pathway leading to CTL recognition of tumor cells seems to operate in all of the cells we tested, including DC. It may lead to new Ag delivery strategies.

Methods

Cells and Functional Assays.

The IGR-Heu cell line was derived from an LCC sample of patient Heu (9). The Heu161 clone was derived from autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (5).

Cytotoxic activity was measured by a conventional 4-h 51Cr-release assay (45). IGR-Heu, Heu-EBV, K562, TT, and DMS53 (European Collection of Cell Cultures) cell lines were used as targets. TNFβ was measured by using the TNF-sensitive WEHI-164c13 cells (46).

Construction and Screening of the cDNA Library.

The cDNA library from IGR-Heu tumor cells was constructed as described previously (9). Plasmid DNA was extracted and cotransfected, together with the expression vector pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) containing an HLA-A*0201 cDNA, into 293-EBNA cells (30,000 cells per well; Invitrogen). After 24 h, Heu161 (3,000 cells per well) was added. After another 24 h, half of the medium was collected, and its TNFβ content was measured.

Sequence Analysis and Localization of the Antigenic Peptide.

cDNA clone 150 was sequenced as described previously (9). To identify the antigenic peptide-encoding region, a panel of cDNA fragments was amplified from cDNA 150 by PCR. PCR products were cloned into expression plasmid pcDNA3.1 by using the Eukaryotic TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and then transferred into the pCEP4 expression vector to allow overexpression.

Chemical Reagents and RNAi.

For proteasomes and SP inhibition, 106 tumor cells were resuspended in media in the presence or absence of specific inhibitors. Briefly, cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C either with epoxomicin or DCI (Sigma), washed, resuspended in acid buffer, and then incubated for additional 3 h in the presence or absence of inhibitors. None of the inhibitors was toxic at the given concentrations. For SPP inhibition, we used siRNA targeting human SPP, siRNA-S1 (5-GACAUGCCUGAAACAAUCAtt-3), and siRNA-S2 (5-UGAUUGUUUCAGGCAUGUCtg-3) (Ambion). Nontargeting siRNA was used as a negative control as described previously (45).

RT-PCR Analyses.

RT-PCR were performed as described previously (47). Forward primer O (5′-ggt gtc atg ggc ttc caa aag t) and reverse primer R (5′-atc agc aca ttc aga agc agg a) (Fig. 2A) were used. PCR conditions were 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 2 min at 63°C, 2 min at 72°C, and a final elongation step of 10 min at 72°C.

Quantitative PCR analysis was performed by using the forward primer 5′-atc ttg gtc ctg ttg cag gc located at the 5′ end of exon 2 and the reverse primer 5′-tgg agc cct ctc tct ctt gct located at the 3′ end of exon 3 of the CALCA gene. The Taq-man probe primer was Fam 5′-cct cct gct ggc tgc act ggt g-3′ Tamra. The amount of RNA samples was normalized by the amplification of RNA 18S. PCR amplifications were performed as described previously (47).

Acknowledgments.

We thank S. Depelchin, C. Richon, and Dr. D. Grunenwald for their help; Drs. K.-I. Hanada, D. Valmori, M. Ayyoub, C. Pinilla, P. Romero, J. Riond, J.-E. Gairin, S. Stevanovic, and P. Van Endert for helpful discussions; and Dr. V. Braud for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche médicale, Institut Gustave Roussy, Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer, Ligue Nationale Française de Recherche contre le Cancer, Fondation de France, and Cancéropôle île de France and the Institut National du Cancer grants; and Association de la Recherche contre le Cancer and Institut National du Cancer fellowships (to F.E.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: Building on success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:383–393. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: Moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Germeau C, et al. High frequency of antitumor T cells in the blood of melanoma patients before and after vaccination with tumor antigens. J Exp Med. 2005;201:241–248. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lurquin C, et al. Contrasting frequencies of antitumor and anti-vaccine T cells in metastases of a melanoma patient vaccinated with a MAGE tumor antigen. J Exp Med. 2005;201:249–257. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Echchakir H, et al. Evidence for in situ expansion of diverse antitumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones in a human large cell carcinoma of the lung. Int Immunol. 2000;12:537–546. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshino I, et al. HER2/neu-derived peptides are shared antigens among human non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3387–3390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogan KT, et al. The peptide recognized by HLA-A68.2-restricted, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is derived from a mutated elongation factor 2 gene. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5144–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karanikas V, et al. High frequency of cytolytic T lymphocytes directed against a tumor-specific mutated antigen detectable with HLA tetramers in the blood of a lung carcinoma patient with long survival. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3718–3724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Echchakir H, et al. A point mutation in the alpha-actinin-4 gene generates an antigenic peptide recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4078–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takenoyama M, et al. A point mutation in the NFYC gene generates an antigenic peptide recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human squamous cell lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1992–1997. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weynants P, et al. Expression of mage genes by non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:826–829. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang SJ, et al. Activation of melanoma antigen tumor antigens occurs early in lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7959–7963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rock KL, Goldberg AL. Degradation of cell proteins and the generation of MHC class I-presented peptides. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:739–779. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayrand SM, Green WR. Non-traditionally derived CTL epitopes: Exceptions that prove the rules? Immunol Today. 1998;19:551–556. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morel S, et al. Processing of some antigens by the standard proteasome but not by the immunoproteasome results in poor presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2000;12:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapatte L, et al. Processing of tumor-associated antigen by the proteasomes of dendritic cells controls in vivo T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5461–5468. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echchakir H, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against a tumor-specific mutated antigen display similar HLA tetramer binding but distinct functional avidity and tissue distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9358–9363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142308199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amara SG, et al. Alternative RNA processing in calcitonin gene expression generates mRNAs encoding different polypeptide products. Nature. 1982;298:240–244. doi: 10.1038/298240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Moullec JM, et al. The complete sequence of human preprocalcitonin. FEBS Lett. 1984;167:93–97. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80839-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg AL, Rock KL. Proteolysis, proteasomes and antigen presentation. Nature. 1992;357:375–379. doi: 10.1038/357375a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banks TA, et al. Vaccination with the immediate-early protein ICP47 of herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1) induces virus-specific lymphoproliferation, but fails to protect against lethal challenge. Virology. 1994;200:236–245. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalbey RE, Lively MO, Bron S, van Dijl JM. The chemistry and enzymology of the type I signal peptidases. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1129–1138. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rusbridge NM, Beynon RJ. 3,4-Dichloroisocoumarin, a serine protease inhibitor, inactivates glycogen phosphorylase b. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80991-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martoglio B, Dobberstein B. Signal sequences: More than just greasy peptides. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:410–415. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01360-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyborg AC, et al. Signal peptide peptidase forms a homodimer that is labeled by an active site-directed gamma-secretase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15153–15160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfeld MG, et al. Production of a novel neuropeptide encoded by the calcitonin gene via tissue-specific RNA processing. Nature. 1983;304:129–135. doi: 10.1038/304129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris HR, et al. Isolation and characterization of human calcitonin gene-related peptide. Nature. 1984;308:746–748. doi: 10.1038/308746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevenson JC, et al. A physiological role for calcitonin: Protection of the maternal skeleton. Lancet. 1979;2:769–770. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92117-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin LA, Heath H., III Calcitonin: Physiology and pathophysiology. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:269–278. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101293040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coombes RC, Hillyard C, Greenberg PB, MacIntyre I. Plasma-immunoreactive-calcitonin in patients with non-thyroid tumours. Lancet. 1974;1:1080–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90557-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milhaud G, et al. Letter: Hypersecretion of calcitonin in neoplastic conditions. Lancet. 1974;1:462–463. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schott M, et al. Calcitonin-specific antitumor immunity in medullary thyroid carcinoma following dendritic cell vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:663–668. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson AE, van Waes MA. The translocon: A dynamic gateway at the ER membrane. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:799–842. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei ML, Cresswell P. HLA-A2 molecules in an antigen-processing mutant cell contain signal sequence-derived peptides. Nature. 1992;356:443–446. doi: 10.1038/356443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson RA, et al. HLA-A2.1-associated peptides from a mutant cell line: a second pathway of antigen presentation. Science. 1992;255:1264–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1546329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aldrich CJ, et al. Identification of a Tap-dependent leader peptide recognized by alloreactive T cells specific for a class Ib antigen. Cell. 1994;79:649–658. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hombach J, Pircher H, Tonegawa S, Zinkernagel RM. Strictly transporter of antigen presentation (TAP)-dependent presentation of an immunodominant cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope in the signal sequence of a virus protein. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1615–1619. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weihofen A, et al. Identification of signal peptide peptidase, a presenilin-type aspartic protease. Science. 2002;296:2215–2218. doi: 10.1126/science.1070925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLauchlan J, Lemberg MK, Hope G, Martoglio B. Intramembrane proteolysis promotes trafficking of hepatitis C virus core protein to lipid droplets. EMBO J. 2002;21:3980–3988. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Targett-Adams P, et al. Signal peptide peptidase cleavage of GB virus B core protein is required for productive infection in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29221–29227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martoglio B, Graf R, Dobberstein B. Signal peptide fragments of preprolactin and HIV-1 p-gp160 interact with calmodulin. EMBO J. 1997;16:6636–6645. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.22.6636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemberg MK, et al. Intramembrane proteolysis of signal peptides: An essential step in the generation of HLA-E epitopes. J Immunol. 2001;167:6441–6446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braud VM, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. 1998;391:795–799. doi: 10.1038/35869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bland FA, et al. Requirement of the proteasome for the trimming of signal peptide-derived epitopes presented by the nonclassical major histocompatibility complex class I molecule HLA-E. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33747–33752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Floc'h A, et al. {alpha}E{beta}7 integrin interaction with E-cadherin promotes antitumor CTL activity by triggering lytic granule polarization and exocytosis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:559–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Espevik T, Nissen-Meyer J. A highly sensitive cell line, WEHI 164 clone 13, for measuring cytotoxic factor/tumor necrosis factor from human monocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1986;95:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(86)90322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazar V, et al. Expression of the Na+/I- symporter gene in human thyroid tumors: a comparison study with other thyroid-specific genes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3228–3234. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.9.5996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]