Abstract

The anti-LPS IgG mAb F22-4, raised against Shigella flexneri serotype 2a bacteria, protects against homologous, but not heterologous, challenge in an experimental animal model. We report the crystal structures of complexes formed between Fab F22-4 and two synthetic oligosaccharides, a decasaccharide and a pentadecasaccharide that were previously shown to be both immunogenic and antigenic mimics of the S. flexneri serotype 2a O-antigen. F22-4 binds to an epitope contained within two consecutive 2a serotype pentasaccharide repeat units (RU). Six sugar residues from a contiguous nine-residue segment make direct contacts with the antibody, including the nonreducing rhamnose and both branching glucosyl residues from the two RUs. The glucosyl residue, whose position of attachment to the tetrasaccharide backbone of the RU defines the serotype 2a O-antigen, is critical for recognition by F22-4. Although the complete decasaccharide is visible in the electron density maps, the last four pentadecasaccharide residues from the reducing end, which do not contact the antibody, could not be traced. Although considerable mobility in the free oligosaccharides can thus be expected, the conformational similarity between the individual RUs, both within and between the two complexes, suggests that short-range transient ordering to a helical conformation might occur in solution. Although the observed epitope includes the terminal nonreducing residue, binding to internal epitopes within the polysaccharide chain is not precluded. Our results have implications for vaccine development because they suggest that a minimum of two RUs of synthetic serotype 2a oligosaccharide is required for optimal mimicry of O-Ag epitopes.

Keywords: antibody complex, carbohydrate, crystal structure, polyliposaccharide, shigellosis

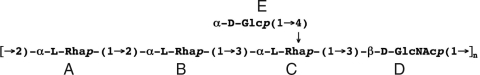

Shigellosis (1), or bacillary dysentery, causes significant morbidity and mortality worldwide, particularly among young children (2). The disease arises from colonization and subsequent destruction of the colonic mucosa by the Gram-negative enteroinvasive bacteria Shigella. Immune protection induced by natural infection derives from antibodies directed against the bacterial surface antigen lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (3). Moreover, protection shows a serotype specificity that is determined by the repeat unit (RU) structure of the O-antigen (O-Ag), the polysaccharide moiety of LPS (4). In the species Shigella flexneri, which is responsible for endemic infections in developing countries, the serotype is defined by glucosyl and O-acetyl modifications added to the basic tri-rhamnose-N-acetyl-glucosamine tetrasaccharide (designated ABCD) of the O-Ag backbone (5). (Serotype 6 is an exception.) Of the 14 S. flexneri serotypes identified to date, the 2a serotype is the most prevalent in developing countries (2). The serotype 2a RU is characterized by a branching glucose (residue E) linked to the third rhamnose (residue C) to form the motif AB(E)CD (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of the 2a serotype O-antigen pentasaccharide repeat unit AB(E)CD.

The induction of protective immunity by natural infection with Shigella suggests that an effective vaccine, based for example on the O-Ag, is possible (1). No approved vaccine, however, is currently available, despite the many candidates in ongoing clinical trials (6). Nonetheless, polysaccharide-protein conjugates qualify as an important breakthrough in the field of antibacterial vaccines, and indeed, promising reports support this approach in the case of shigellosis (7, 8). As an alternative to classical polysaccharide conjugate vaccines, we have developed a strategy based on synthetic carbohydrates that mimic the O-Ag of S. flexneri 2a, including a detailed analysis of the fine specificity of protective antibody/O-Ag recognition. Accordingly, a number of oligosaccharides representative of serotype 2a O-Ag fragments have been synthesized (9–11). Although several of these were immunogenic in mice when administered as tetanus toxoid conjugates, only certain sequences were able to induce IgG antibodies capable of recognizing the bacterial LPS (12, 13). Of particular note, the capacity of these synthetic glycoconjugates to induce IgG titers cross-reactive with LPS depended on the number of RUs present.

The synthetic oligosaccharides were also tested for their affinity to five serotype-specific murine IgG mAb that we produced by infection with homologous bacteria (12). Of these five mAbs, all of which gave protection in a mouse model of infection, mAb F22-4 was unique in its binding pattern to different synthetic serotype 2a oligosaccharides and its variable domain sequence. For example, only F22-4 bound the trisaccharide ECD, the smallest oligosaccharide to be recognized (12). As part of our general strategy, we have determined the crystal structure of the Fab fragment of IgG F22-4 in complex with the synthetic decasaccharide and pentadecasaccharide ligands, [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 (11), respectively. The structures show that both ligands are bound in an identical way: Six carbohydrate residues, contained within a contiguous nonasaccharide segment, make direct contacts with F22-4. These results are compared with other antibody–carbohydrate structures and are discussed in the light of antigenic and immunogenic mimicry of S. flexneri 2a O-Ag by synthetic oligosaccharides that we have previously reported (12, 13).

Results

General Description of the Fab F22-4 Structures.

The Fab fragment of F22-4 was crystallized in the nonliganded form, and in complex with the amino-ethyl derivatives of the decasaccharide [AB(E)CD]2 (9) and the pentadecasaccharide [AB(E)CD]3 (10), respectively. Crystals of Fab F22-4 are triclinic with two independent molecules in the unit cell. The crystals of both oligosaccharide complexes are monoclinic, with very similar unit cell dimensions and containing four complexes in the asymmetric unit; however, they are not strictly isomorphous to each other because of differences in the Fab elbow angles between the two crystal forms.

The complete [AB(E)CD]2 ligand is visible in the electron density maps for all four independent complexes; however, only 11 residues could be traced in each of the four independent [AB(E)CD]3 complexes. Interactions of [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 with F22-4 are essentially identical, covering two consecutive RUs (designated here as AB(E)CDA′B′(E′)C′D′). For [AB(E)CD]3, binding modes could conceivably involve the first and second RUs, the second and third, or indeed a mixture of these two possibilities. Examination of the electron density maps, however, indicates that only the first mode is used; although density for the 11th residue, Rha(A″) [after GlcNAc(D′)], is present, there is no density preceding the first visible rhamnose [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Modeling confirms these observations because it shows that extension of the oligosaccharide by addition of GlcNAc(D°) to the nonreducing end of the first built rhamnose leads either to steric hindrance with the antibody or to unfavorable conformations for the D°A linkage.

Antigen-Binding Site.

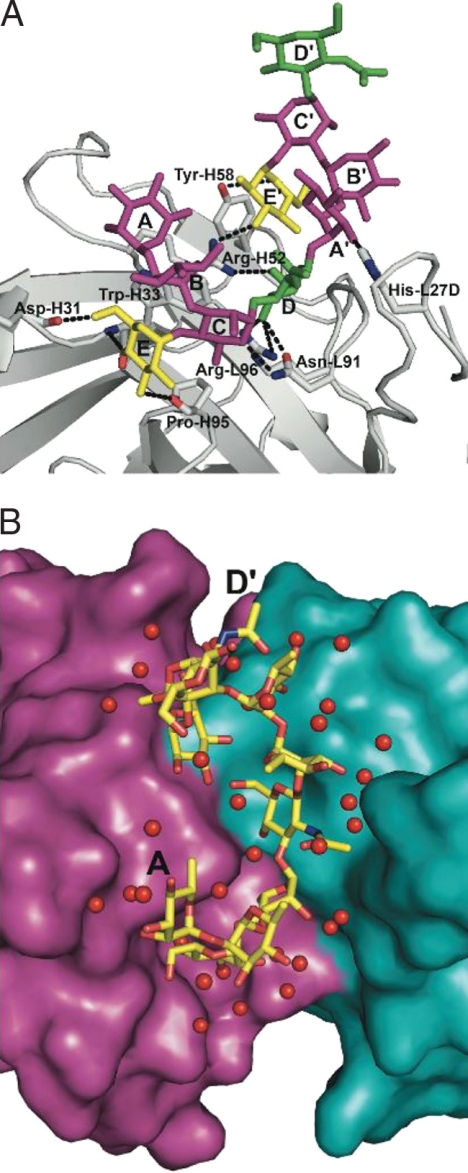

The antigen-binding site is groove shaped, with approximate dimensions of 20 Å long, 15 Å wide, and 8 Å deep (Fig. 2). It is formed by CDR-L1 on one side of the groove, and CDR-H1 and CDR-H2 on the other, with CDR-L3 and CDR-H3 at the floor of the binding site. An unusual feature of CDR-H3, apart from its short length (four residues), is a cis peptide bond between Pro-H95 and Met-H96, present in both the liganded and free forms of F22-4. Although the F22-4 structure was determined in both the free and antigen-bound state, the presence of significant intermolecular contacts at the binding site of the noncomplexed Fab fragments limits conclusions on changes in conformation and solvation upon complex formation.

Fig. 2.

Views showing the interaction between F22-4 and [AB(E)CD]2 (see Fig. S2 for stereoview). (A) A detailed view of [AB(E)CD]2 bound to F22-4. Rha residues are in purple, Glc are in blue and GlcNAc are in green. The antibody is shown in ribbon form with residues hydrogen bonding to the ligand in atomic form. Antibody–antigen hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines. (B) View from above the antigen-binding site. The variable domains of F22-4 are shown in surface representation with the VH domain in purple and the VL domain in blue. [AB(E)CD]2 is shown in atomic form with carbon in yellow, oxygen in red, and nitrogen in blue. Water molecules bound to [AB(E)CD]2 (and in some cases to the antibody as well) are shown as red spheres.

Structure of the Carbohydrates.

The mean pairwise r.m.s. difference in atomic positions of the four independent saccharides is 0.18 Å for [AB(E)CD]2 and 0.43 Å for [AB(E)CD]3; a pairwise comparison between [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 gives a mean r.m.s. difference of 0.30 Å. Thus, [AB(E)CD]2 is very similar in all four independent complexes; the moderately larger r.m.s. differences for [AB(E)CD]3 essentially reflect the larger deviations for residues GlcNAc(D′) and Rha(A″) at the reducing end, which make no contacts with the Fab. The lack of electron density beyond residue Rha(A″) of the third RU can be attributed to the absence of stabilizing intermolecular contacts in this region of [AB(E)CD]3 and to its intrinsic flexibility.

The backbone dihedral angles (φ,ψ) of the two RUs (ABCD and A′B′C′D′) are similar to each other in both the [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 complexes (Table 1 and Fig. S3). ABCD superimposes on A′B′C′D′ with a r.m.s. difference of 0.44 Å (mean value for the four independent ligands) with all backbone atom positions for [AB(E)CD]2 and 0.53 Å for [AB(E)CD]3. Moreover, the dihedral angles at the AB, BC, and CD linkages fall into theoretical energy minima based on disaccharide models α-l-Rhap-(1->2)-α-l-Rhap, α-l-Rhap-(1->3)-α-l-Rhap and α-l-Rhap-(1->3)-β-d-GlcpNAc) (Fig. S4) (14). By contrast, the DA′ linkage falls in a less favorable, although allowed, region of the theoretical β-d-GlcpNAc-(1->2)-α-l-Rhap disaccharide energy diagram. This could be due to limitations from using a disaccharide model, which includes neither the influence of antibody contacts nor a bifurcated intramolecular hydrogen bond from O5D to O3E and O4E′, nor the many solvent molecules that form intraoligosaccharide-bridging interactions (Fig. 2). The dihedral angles of the two branching α-d-Glcp-(1->4)-α-l-Rhap linkages (EC and E′C′) differ widely from each other. They are not close to minima in the theoretical disaccharide energy diagram, probably reflecting the important influence of the Fab on the conformation of these branching linkages (see below). Interestingly, if Glc(E′) is modeled with the same dihedral conformation as Glc(E), an internal hydrogen bond is also formed to GlcNAc(D) (via O6D and O6E in this case).

Table 1.

Saccharide (φ,ψ) dihedral angles

| Saccharide | [AB(E)CD]2 (2a) | [AB(E)CD]3 (2a) | [lABCDA′] (Y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rha(A)-Rha(B) | −86°, −167° | −91°, −166° | −64°, −92° |

| Rha(B)-Rha(C) | −78°, −128° | −75°, −127° | −82°, −116° |

| Rha(C)-GlcNAc(D) | −92°, 134° | −89°, 132° | −115°, 145° |

| GlcNAc(D)-Rha(A′) | −67°, −139° | −66°, −138° | −90°, 177° |

| Glc(E)-Rha(C) | 146°, 147° | 145°, 151° | |

| Rha(A′)-Rha(B′) | −80°, −146° | −81°, −149° | |

| Rha(B′)-Rha(C′) | −70°, −129° | −74°, −127° | |

| Rha(C′)-GlcNAc(D′) | −85°, 126° | −90°, 144° | |

| Glc(E′)-Rha(C′) | 56°, 95° | 49°, 95° | |

| GlcNAc(D′)-Rha(A″) | −81°, −126° |

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry convention (www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/misc/psac.html). Mean values from the four crystallographically independent molecules are given for the 2a serotype [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 complexes and for the Y serotype pentasaccharide (ABCDA′) complex with mAb SYA/J6 (PDB ID 1m7i).

Antibody–Carbohydrate Interactions.

The epitope is contained within two consecutive RUs, requiring the nonasaccharide AB(E)CDA′B′(E′)C′ to present the complete antigenic determinant (sugar residues in contact with F22-4 are in italics). All hypervariable regions except CDR-L2 contact the antigen. Eleven hydrogen bonds are formed directly between the Fab and [AB(E)CD]2 (Table 2). Fourteen water molecules, common to the four independent complexes, bridge between the two components (Fig. 2B). The total buried accessible surface area at the antibody–antigen interface is 1,125 Å2 [calculated by using a solvent probe radius of 1.4 Å with the program AREAIMOL (15)]. The bridging water molecules make an important contribution to complementarity at the interface because the surface complementarity index [calculated with the program SC (15)] increases from 0.65 to 0.75 when they are included in the calculation.

Table 2.

Hydrogen bond interactions between F22-4 and oligosaccharide

| Saccharide | F22-4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rha(C) | O5 | Asn | L91 | Nδ2 |

| GlcNAc(D) | O4 | Asn | L91 | Oδ1 |

| Arg | L96 | Nζ1 | ||

| Arg | L96 | Nζ2 | ||

| GlcNAc(D) | O6 | Arg | H52 | Nζ2 |

| Glc(E) | O3 | Pro | H95 | O |

| Glc(E) | O4 | Trp | H33 | N |

| Glc(E) | O6 | Asn | H31 | O |

| Rha(A′) | O3 | His | L27D | Nε2 |

| Glc(E′) | O3 | Arg | H52 | Nζ1 |

| Glc(E′) | O5 | Tyr | H58 | OH |

Table 3 summarizes F22-4 interactions with individual oligosaccharides residues. GlcNAc(D) and the branching residue Glc(E) make the most important contributions. These two residues are the most buried, being located in small cavities in the groove-shaped binding site. The two cavities are formed largely by a narrowing of the groove by residues Asn-L91, Arg-L96, and Trp-H33 located at the center of the binding site. Rha(C) and Glc(E′) make intermediate contributions, whereas those of Rha(A), Rha(A′) and Rha(B′) are weak. In the case of Rha(B′), the only contacts are mediated by bridging water molecules. Rha(B), Rha(C′), and GlcNAc(D′) make no contacts at all with the antibody.

Table 3.

Summary of the interactions per saccharide residue

| Residues | A | B | C | D | E | A′ | B′ | C′ | D′ | E′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contacts | 2 | – | 7 | 14 | 13 | 3 | – | – | – | 7 |

| H bonds | – | – | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| Water bridges | 2 | – | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | – | – | 1 |

| Buried surface | 68 | 1 | 80 | 161 | 148 | 35 | 26 | 2 | 0 | 86 |

The number of interatomic contacts (<3.8 Å) between the antibody and oligosaccharide as well as the number of these that are hydrogen bonds are given in the first and second lines, respectively. The numbers of water molecules bridging between the antibody and oligosaccharide are given in the third line. The buried surface area of each saccharide residue at the antibody/antigen interface is calculated by using a spherical probe of 1.4 Å radius.

Discussion

Comparison with Other Antibody–Carbohydrate Complexes.

Early work on anti-polysaccharide antibodies suggested that carbohydrate epitopes could vary from one to approximately seven residues, the upper limit being determined by the surface available at the antigen-binding site (16). It was concluded that small epitopes generally include the nonreducing terminal residue, whereas larger epitopes are located along the length of the polysaccharide chain (17). It was further suggested that small epitopes bind to cavity-type antigen-binding-site topologies, whereas larger internal epitopes are recognized by groove-type topologies (18). Although few bacterial oligosaccharide–antibody crystal structures have been reported to date (19–21), these early estimates of epitope size and nature, and their relationship to binding-site topology, are largely concordant with current structural data. For example, the crystal structure of mAb S-20–4, raised against the O-Ag of Vibrio cholerae O1 serotype Ogawa, shows that a disaccharide, corresponding to the nonreducing terminus of the cognate antigen, binds to a cavity-shaped binding site (20). The structure suggests that the epitope recognized by S-20-4 comprises essentially two sugar rings at the terminus of the cognate polysaccharide antigen. By contrast, mAb SYA/J6, raised against S. flexneri serotype Y O-Ag (where the RU is ABCD), binds an extended pentasaccharide in a groove-shaped binding site (21). An upper limit of approximately seven sugar units in the antigen-binding site is also largely substantiated by recent structural studies. Antibody Se155-4, which recognizes the Salmonella serotype B O-antigen, has been crystallized with an octasaccharide (22) and dodecasaccharide (19); the octasaccharide complex shows that six of the seven ordered residues make direct contact with Se155-4. However, the minimum oligosaccharide length may require more sugar units in some cases to provide the optimal number of antibody-contacting residues. With a helical polysaccharide chain, for example, the antibody-contacting residues would not form a contiguous segment because some sugar units would be solvent-exposed, as suggested from modeling studies by Evans et al. (23).

The epitope in the F22-4–oligosaccharide complexes is included within a contiguous nine-residue section in which six sugar rings make direct contacts with the antibody. Thus, a more compact oligosaccharide conformation—in this case helical—presents a longer segment that still conforms to the approximate seven-residue limit at the antigen-binding site. As might be anticipated, the binding site is groove-shaped to accept an epitope of this size, but this topology is modulated by two cavities. The larger cavity accommodates the branching Glc(E) residue. A similar situation occurs in the structure of the anti-Salmonella O-polysaccharide mAb Se115-4 complex (19), where the branching abequose ring of the antigen binds in a cavity located centrally in the binding site. A branching residue on a polysaccharide chain can therefore behave as a nonreducing terminus. The second (smaller) cavity of F22-4, by contrast, binds the backbone residue GlcNAc(D) and thus resembles the SYA/J6 complex, where Rha(C) of the serotype Y ligand ABCDA′ is also buried in a cavity at the center of the groove-shaped binding site (21).

Comparison between F22-4 and SYA/J6 merits further discussion because of similarity with respect to both the cognate antigen and the VH sequence. SYA/J6 was raised against S. flexneri serotype Y O-Ag, which lacks a branching residue. VH of SYA/J6 uses the same germ-line VH gene and JH minigene as F22-4, the major difference being in the length of CDR-H3 (nine residues in SYA/J6 and four in F22-4) (Table S1). The complete SYA/J6 VL domain, however, originates from different VL and Jk genes and shows 28 differences over 112 residues with respect to F22-4. The binding site of F22-4 is shallower than that of SYA/J6, mainly because a salt bridge is formed between Arg-L96 and Glu-H50 in F22-4 (Arg-L96 is deleted from the SYA/J6 VL germ-line sequence). Consequently, the serotype Y ABCDA′ segment sits lower in the antibody framework than does the serotype 2a antigen. The short CDR-H3 of F22-4 results in a deep pocket for the Glc(E) residue, where many polar interactions between antibody and oligosaccharide are mediated by buried solvent molecules. Indeed, the highly solvated antibody/antigen interface of F22-4 contrasts with the absence of bridging water molecules in the SYA/J6 complex. Although the serotype Y lacks the branching glucose, the two antigen serotypes are remarkably close in conformation for the segment BCD. These superimpose with an r.m.s. difference of 0.73 Å in all atom positions, reflecting the similarities in the (φ,ψ) dihedral angles of the BC and CD glycosidic linkages (Table 1 and Fig. S5).

Influence of Glucosylation on O-Antigen Conformation.

Addition of the α-d-Glcp(E)-(1->4)-α-l-Rhap(C) serotype 2a conformation observed in the F22-4 complex to the ABCDA′ serotype Y structure of the SYA/J6 complex shows that Glc(E) would be sterically hindered by Rha(A), thereby forcing the AB φ dihedral angle to more negative values, as observed in the F22-4 complex (Table 1). The AB glycosidic linkages in both the F22-4 and SYA/J6 complexes are indeed in energy minima in the (φ,ψ) plot (Fig. S4), showing that both observed AB conformations in the two serotypes are favorable. Similarly, the α-d-Glcp(E)-(1->3)-α-l-Rhap(B) linkage of the 5a serotype is not sterically compatible with the Y serotype structure, as has been previously noted (24). The pattern of serotype glucosylation can therefore impose constraints on the structure of extended O-Ag chains.

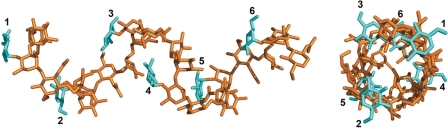

Implications for O-Antigen Structure in LPS.

By iterative superposition of ABCD onto A′B′C′D′ using the crystallographic [AB(E)CD]2 coordinates, we could generate a model for an extended serotype 2a O-Ag chain that was devoid of unfavorable steric interactions. This model comprises RUs with the crystallographic glycosidic (φ,ψ) angles of the A′B′(E′)C′D′ moiety and the DA′ linkage; no energy optimization was attempted to preserve the experimentally determined linkage conformations (Fig. 3). (An almost identical model was generated when the AB(E)CD conformation was used in this procedure.) The model polysaccharide chain thus obtained is a right-handed helix of pitch ≈23 Å, diameter ≈15 Å, and nearly three RUs per turn. Interestingly, the helix has similar parameters to the model proposed for serotype 5a O-Ag, which was based on NMR data and modeling studies (24). But unlike the serotype 5a model, where Glc(E) protrudes outwards perpendicular to the helical axis in a solvent-exposed orientation, Glc(E) in the serotype 2a is folded under the backbone at approximately the same radial distance from the helical axis as the residues ABCD. This is true for both the EC and E′C′ conformations present in the crystal structure. Glc(E) is therefore less accessible than in the serotype 5a model, where linkage to the ABCD base differs (α-d-Glcp(E)-(1->3)-α-l-Rhap(B)). If this hypothetical structure does indeed exist in 2a serotype O-Ag, it would probably represent a relatively transient short-range ordering because intrinsic mobility is indicated by the absence of electron density for all but the first residue of the third RU in the [AB(E)CD]3 complex. Conformational flexibility is expected because, apart from the hydrogen bond formed between GlcNAc(D) and Glc(E′), intramolecular contacts between carbohydrate residues are exclusively mediated by bridging solvent molecules. Nonetheless, it represents a plausible average structure because the backbone conformation within the ABCD motif is conserved between the two RUs in the crystal structure, and their glycosidic dihedral angles are in favorable conformations.

Fig. 3.

Views of the helical model of serotype 2a O-Ag generated from the structure of the F22-4/oligosaccharide complexes as described in Implications for O-Antigen Structure in LPS. The two views are orthogonal and are taken perpendicular and parallel to the helical axis. Six RUs are shown, corresponding to almost two complete helical turns. The backbone residues are shown in brown, and the branching glucose residues are in cyan. The glucose residues are numbered according to the RU to which they belong, beginning from the nonreducing end.

Correlation of Crystal Structure with Oligosaccharide Binding Studies.

The network F22-4/oligosaccharide interactions revealed by the crystal structures is largely concordant with the LPS/F22-4 inhibition studies using 24 synthetic S. flexneri 2a di- to pentadecasaccharides (12, 13). ECD, the smallest synthetic segment of the serotype 2a O-Ag that gave measurable competitive binding to F22-4, corresponds to the contiguous trisaccharide segment making the most significant interactions with F22-4 (Table 3). The pentasaccharide AB(E)CD was approximately an order of magnitude more effective in inhibition than ECD whereas the octasaccharide B(E)CDA′B′(C′)D′, which represents essentially the entire structural epitope, was approximately three orders of magnitude more effective. Oligosaccharides that included neither GlcNAc(D) nor Glc(E) showed no measurable binding, consistent with the key contribution of these residues to antibody–antigen interactions.

We have argued from the crystal structures that the addition of GlcNAc(D°) to the nonreducing end of the bound oligosaccharide would lead either to steric hindrance with F22-4 or to unfavorable D°A glycosidic conformations. Nonetheless, the IC50 of D°AB(E)CDA′B′(E′)C′ is only an order of magnitude higher than that of B(E)CDA′B′(E′)C′ (12), suggesting that steric hindrance between D° and F22-4 could be relieved by conformational changes, most probably in both the AB and BC glycosidic bonds. Thus, although the crystal structures imply that inclusion of the nonreducing terminus of LPS in the epitope gives a more favorable interaction with F22-4, the binding data suggest that recognition of internal epitopes along the O-Ag chain also occurs, but probably with reduced affinity.

Structural Implications for Vaccine Development.

An important parameter in oligosaccharide-based vaccine development is the minimum hapten length required to give optimal immune protection. In some cases, disaccharide– or trisaccharide–protein conjugates are able to induce a protective antipolysaccharide response in animal models, showing that for certain bacterial polysaccharide antigens, synthetic oligosaccharides shorter than one RU can be good immunogenic mimics (25, 26). For other polysaccharide antigens, however, several RUs may be required to obtain immunogenic mimicry (27); here, it has been suggested that the corresponding epitopes might be conformational in certain cases (28). Our previous studies have suggested that a correlation exists between the synthetic oligosaccharide length and immunogenic mimicry of serotype 2a LPS (12, 13). Antibodies induced by a glycoconjugate bearing one synthetic RU showed only weak reactivity with bacterial LPS, and antibodies induced by two RUs showed medium reactivity; but those induced by three RUs were highly reactive. Accordingly, the dependence of immunogenic mimicry on RU number suggests that immunodominant serotype 2a epitopes might also be conformational, requiring longer segments for the presentation of more stable structures such as the helical form we have proposed. This possibility, however, needs further examination because other factors could account for our observations.

Characterization of antigenic determinants is equally important for vaccine development. Our results provide a structural perspective for understanding the serotype 2a specificity of F22-4, revealing a significant contribution to the epitope from the branching glucosyl residues of two consecutive RUs. A minimum segment of nine consecutive sugar units is required to present the complete epitope recognized by F22-4. Accordingly, glycoconjugates should probably carry a minimum of two serotype 2a RUs to achieve a broad antigenic mimicry of the O-Ag. The conformation of the antigen, as seen in the crystal structures, is strongly influenced by the position of the branching sugars on the backbone, underlining the need to determine the extent of restraints on the conformational variability in synthetic oligosaccharides and to clarify the consequences for antigenic mimicry. To this end, there is an interest in cocrystallizing oligosaccharides with other anti-serotype 2a mAbs that recognize different epitopes to extend our knowledge of O-Ag conformation and its implications for immune recognition.

Materials and Methods

Crystallization and Data Collection.

Fab F22-4 was prepared from purified IgG by papain digestion. Crystallizations were performed by using the hanging-drop technique. Crystals of the free Fab were grown at 17°C from the buffer Clear Strategy Screen solution no. I-3 (Molecular Dimensions) mixed with 5% 1 M sodium acetate at pH 4.5. The final protein concentration was 4.1 mg/ml. Crystals of the Fab complexes were obtained by cocrystallizing with the aminoethyl derivatives of [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 at molar excesses of 1:10 and 1:16, respectively, by using the buffer JBScreen Classic 4-A1 (Jena Bioscience). Final protein concentrations were 4.0 and 3.1 mg/ml for the [AB(E)CD]2 and [AB(E)CD]3 complexes, respectively. Diffraction data were collected at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France. The data were processed by using the programs XDS (29) and the CCP4 program suite (15). Details of the data collection and statistics are given in Table S2.

Structure Solution and Refinement.

Initial models of the free Fab and the two complexes were obtained by molecular replacement using the programs AMoRe (30) and Phaser (31). Known antibody structures were used as search models. The structures were refined by using the programs REFMAC (32) and ARP/warp (33). The oligosaccharides in the complexes were built during the early stages of the refinement. Refinement statistics are given in Table 4. Figures of molecular structures were made with MacPyMol (www.pymol.org).

Table 4.

Refinement statistics

| Free Fab | Decasaccharide complex | Pentadecasaccharide complex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution, Å | 72–2.0 | 48–1.8 | 45–1.8 |

| Last shell, Å | 2.03–2.00 | 1.82–1.80 | 1.82–1.80 |

| R value (working set) | 0.199 (0.246) | 0.176 (0.257) | 0.191 (0.281) |

| Rfree | 0.260 (0.411) | 0.230 (0.278) | 0.251 (0.354) |

| No. of reflections (total) | 50,671 (1,737) | 182,354 (6,631) | 176,903 (6,431) |

| No. of reflections for Rfree | 1,307 (35) | 2,708 (91) | 2,670 (97) |

| No. of protein atoms | 6,482 | 13,193 | 13,150 |

| No. of carbohydrate atoms | — | 447 | 479 |

| No. of solvent atoms | 400 | 2,474 | 2,123 |

| R.m.s. deviation from ideal | |||

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.014 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 |

SI.

Additional Materials and Methods may be found in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the staff of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France, for providing facilities for diffraction measurements and for assistance. This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and the Ministère National de la Recherche et de la Technologie. F.B. was supported by a Roux Fellowship, Institut Pasteur.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: A.P. and L.A.M. are inventors on patent WO 2055/003775 A3.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3C5S, free Fab; 3BZ4, [AB(E)CD]2 complex; and 3C6S, [AB(E)CD]3 complex).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801711105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Niyogi SK. Shigellosis. J Microbiol. 2005;43:133–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, et al. Global burden of Shigella infections: Implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:651–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennison AV, Verma NK. Shigella flexneri infection: Pathogenesis and vaccine development. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindberg AA, Karnell A, Weintraub A. The lipopolysaccharide of Shigella bacteria as a virulence factor. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:S279–284. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_4.s279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison GE, Verma NK. Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Barry EM, Pasetti MF, Sztein MB. Clinical trials of Shigella vaccines: Two steps forward and one step back on a long, hard road. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:540–553. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passwell JH, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of improved Shigella O-specific polysaccharide–protein conjugate vaccines in adults in Israel. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1351–1357. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1351-1357.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Passwell JH, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of Shigella sonnei-CRM9 and Shigella flexneri type 2a-rEPAsucc conjugate vaccines in one- to four-year-old children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:701–706. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000078156.03697.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belot F, Wright K, Costachel C, Phalipon A, Mulard LA. Blockwise approach to fragments of the O-specific polysaccharide of Shigella flexneri serotype 2a: Convergent synthesis of a decasaccharide representative of a dimer of the branched repeating unit. J Org Chem. 2004;69:1060–1074. doi: 10.1021/jo035125b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright K, Guerreiro C, Laurent I, Baleux F, Mulard LA. Preparation of synthetic glycoconjugates as potential vaccines against Shigella flexneri serotype 2a disease. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:1518–1527. doi: 10.1039/b400986J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belot F, Guerreiro C, Baleux F, Mulard LA. Synthesis of two linear PADRE conjugates bearing a deca- or pentadecasaccharide B epitope as potential synthetic vaccines against Shigella flexneri serotype 2a infection. Chemistry. 2005;11:1625–1635. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phalipon A, et al. Characterization of functional oligosaccharide mimics of the Shigella flexneri serotype 2a O-antigen: Implications for the development of a chemically defined glycoconjugate vaccine. J Immunol. 2006;176:1686–1694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulard LA, Phalipon A. From epitope characterization to the design of semisynthetic glycoconjugate vaccines against Shigella flexneri 2a infection. Carbohydrate-based vaccines. In: Roy R, editor. ACS Symp Ser no 989. Washington, DC: Am Chem Soc; 2008. pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank M, Lutteke T, von der Lieth CW. GlycoMapsDB: A database of the accessible conformational space of glycosidic linkages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:287–290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collaborative Computing Project 4. The CCP4 Suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabat EA. The nature of an antigenic determinant. J Immunol. 1966;97:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cisar J, Kabat EA, Dorner MM, Liao J. Binding properties of immunoglobulin combining sites specific for terminal or nonterminal antigenic determinants in dextran. J Exp Med. 1975;142:435–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padlan EA, Kabat EA. Model-building study of the combining sites of two antibodies to alpha (1→6)dextran. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6885–6889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cygler M, Rose DR, Bundle DR. Recognition of a cell-surface oligosaccharide of pathogenic Salmonella by an antibody Fab fragment. Science. 1991;253:442–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1713710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villeneuve S, et al. Crystal structure of an anti-carbohydrate antibody directed against Vibrio cholerae O1 in complex with antigen: Molecular basis for serotype specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8433–8438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060022997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vyas NK, et al. Molecular recognition of oligosaccharide epitopes by a monoclonal Fab specific for Shigella flexneri Y lipopolysaccharide: X-ray structures and thermodynamics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13575–13586. doi: 10.1021/bi0261387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cygler M, Wu S, Zdanov A, Bundle DR, Rose DR. Recognition of a carbohydrate antigenic determinant of Salmonella by an antibody. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:437–441. doi: 10.1042/bst0210437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans SV, et al. Evidence for the extended helical nature of polysaccharide epitopes. The 2.8 A resolution structure and thermodynamics of ligand binding of an antigen binding fragment specific for a-(2→8)-polysialic acid. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6737–6744.5. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clement MJ, et al. Conformational studies of the O-specific polysaccharide of Shigella flexneri 5a and of four related synthetic pentasaccharide fragments using NMR and molecular modeling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47928–47936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308259200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goebel WF. Studies on antibacterial immunity induced by artificial antigens. J Exp Med. 1939;69:353–364. doi: 10.1084/jem.69.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benaissa-Trouw B, et al. Synthetic polysaccharide type 3-related di-, tri-, and tetrasaccharide-CRM(197) conjugates induce protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae type 3 in mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4698–4701. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4698-4701.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pozsgay V, et al. Protein conjugates of synthetic saccharides elicit higher levels of serum IgG lipopolysaccharide antibodies in mice than do those of the O-specific polysaccharide from Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5194–5197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laferriere CA, Sood RK, de Muys JM, Michon F, Jennings HJ. Streptococcus pneumoniae type 14 polysaccharide-conjugate vaccines: Length stabilization of opsonophagocytic conformational polysaccharide epitopes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2441–2446. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2441-2446.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabsch W. Evaluation of single crystal x-ray diffraction data from a position-sensitive detector. J Appl Crystallogr. 1989;21:916–924. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navaza J. Implementation of molecular replacement in AMoRe. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:1367–1372. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D. 2007;63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pannu NS, Murshudov GN, Dodson EJ, Read RJ. Incorporation of prior phase information strengthens maximum-likelihood structure refinement. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:1285–1294. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998004119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perrakis A, Sixma TK, Wilson KS, Lamzin VS. wARP: Improvement and extension of crystallographic phases by weighted averaging of multiple-refined dummy atomic models. Acta Crystallogr D. 1997;53:448–455. doi: 10.1107/S0907444997005696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.