Abstract

Cancer of the urinary bladder is often a result of exposure to chemical carcinogens. Models of this disease have been developed by exposing rodents to N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine (OH-BBN). The resultant tumors are histologically similar to human disease, but little is known about genetic similarities to the latter. Such knowledge would help identify or corroborate genes found important in human bladder cancer and suggest biologically appropriate mechanistic studies. We address this need by comparing gene expression profiles associated with urothelial carcinoma for three different species: mouse, rat, and human. We find that many human genes homologous to those differentially expressed in carcinogen-induced rodent tumors are also differentially expressed in human disease and are preferentially associated with progression from non-muscle-invasive to muscle-invasive disease. We also find that overall gene expression profiles of rodent tumors correspond more closely with those of invasive human tumors rather than non-muscle-invasive tumors. Finally, we provide a list of genes that are likely candidates for driving this disease process by virtue of their concordant regulation in tumors of all three species.

Introduction

Cancer of the urinary bladder is the fourth most common newly diagnosed cancer in men in the United States, with 51,230 new diagnoses predicted in 2008, and will be responsible for an estimated 14,100 deaths [1]. Most bladder tumors in the western world are of urothelial (“transitional”) cell histology and are categorized according to cellular grade and the extent to which the tumor invades the surrounding tissues. The prognosis is good for those with non-muscle-invasive tumors, whereas those with muscle-invasive disease are at increased risk of metastasis and death [2]. Having robust and clinically relevant animal models for the mechanistic study of the causes underlying carcinogenesis, tumor progression, and metastasis of urothelial carcinoma would improve treatment and prognosis for patients with bladder cancer.

Many bladder cancers result from exposure to chemical carcinogens. It is estimated that one third to one half of bladder tumors are associated with cigarette smoking [3,4]. Whereas the specific causative agent in cigarette smoke remains unidentified, α- and β-naphthylamine are suspected. Occupational exposure to aromatic amines such as β-naphthylamine, 4-aminobiphenyl, benzidine, and 2-amino-1-naphthol, among other chemicals, accounts for an additional 20% to 30% of bladder cancer cases in the United States [5,6].

Given the importance of chemical carcinogenesis to the development of bladder cancer, we sought to evaluate the degree of molecular similarity of two commonly used primary rodent models of this disease to human bladder cancer. Both models involve the administration of N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine (OH-BBN) to mice [7,8] or rats [9–11]. Second, if molecular similarity did exist, we sought to determine, by virtue of cross-species comparison, which genes were the most important in bladder tumor development and progression, thus providing promising leads for future research. Experiments profiling the gene expression of normal urothelium and OH-BBN-induced bladder tumors in both rat and mice have been published [12,13], providing an opportunity to address these important questions.

Methods

Human Bladder Cancer Microarrays

We constructed a human bladder cancer gene expression data set of 53 previously published Affymetrix HG-U133A GeneChips, including normal urothelial tissue and both non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive tumors. Data from 30 microarray chips were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus Web site (GEO Accession Number GSE3167) [14–16], whereas those of 23 chips were obtained locally [17]. The clinical characteristics of the characterized tissues are summarized in Table 1. Microarray profiles were classified according to the type of tissue hybridized to the chip. Fifteen chips were hybridized with RNA from normal urothelium, 14 chips with non-muscle-invasive bladder tumors (defined as stage Ta or T1 tumors with grade less than 3), and 24 chips with muscle-invasive bladder tumors (defined as stage T2 or greater, any grade). We used the Robust Multichip Average method to quantile-normalize, background-adjust, and summarize the gene expression values from these chips [18–20].

Table 1.

Stage and Grade of Human Bladder Cancer Specimens.

| Stage | Grade (1–4) | N |

| Normal | n/a | 15 |

| Ta | 1 | 1 |

| Ta | 2 | 10 |

| T1 | 2 | 3 |

| T2 | 2 | 1 |

| T2 | 3 | 4 |

| T3 | 3 | 6 |

| T3 | 4 | 3 |

| T4 | 2 | 1 |

| T4 | 3 | 9 |

Rodent Bladder Cancer Microarrays

Yao et al. [12] found 1554 mouse genes differentially expressed between bladder cancer and normal urothelial tissue with a t test P value < .05 and fold change ≥ 2, 867 of which were overexpressed and 687 underexpressed in the tumors. They published 53 overexpressed and 37 underexpressed genes along with fold change values. In a similar study, they found 1138 rat genes to be differentially expressed with a t test P value < .05 and fold change ≥ 2, 770 of which were overexpressed and 368 underexpressed in the tumors. They published 98 overexpressed and 47 underexpressed genes or transcripts with fold change values [13].

Homology and Statistical Analysis of Bladder Cancer Microarrays

We used the NetAffx information site (http://www.affymetrix.com) to determine which human Affymetrix HG-U133A probe sets were homologous with the published rodent genes [21] (Figure 1A). Because Yao et al. [12] used Affymetrix MG-U74Av2 and Rat 230 2.0 GeneChips to measure gene expression in the normal and cancerous tissues, we first determined which MG-U74Av2 probe sets correspond to the accession numbers of the listed mouse genes and which Rat 230 2.0 probe sets correspond to the listed rat genes or transcript accession numbers. We then found the HG-U133A probe sets that were homologous to these matched mouse and rat genes. Some rodent genes had multiple human homologs, whereas others had none. No human probe sets were homologous to more than one mouse or rat gene, with the exception of 201429_s_at and 202240_at, which were homologous to Plk and Plk-ps1. Because Plk-ps1 is a pseudogene, we used the fold change value for Plk in subsequent analyses. For simplicity, we refer to the human probe sets homologous to the genes differentially expressed between tumor and normal bladder in the rodent as “mouse homologs” and “rat homologs” respectively and collectively as “rodent homologs”.

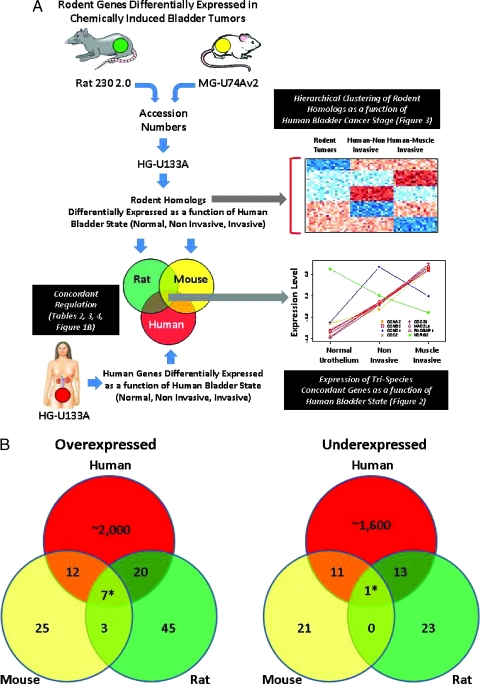

Figure 1.

(A) Diagrammatic representation of the analysis workflow and results. (B) Venn diagrams showing the numbers of genes differentially regulated in human, mouse, and rat and concordantly regulated. Shown are genes overexpressed or underexpressed in tumors compared to normal urothelium. Asterisk (*) indicates genes whose pattern of expression is shown in Figure 2.

To examine the importance of individual rodent homologs to transformation (normal vs cancer) and progression in humans, we first used Student's t test to determine the significance of the difference in expression between normal urothelium and non-muscle-invasive cancer, between normal urothelium and muscle-invasive cancer, between non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive cancer, and between normal and cancerous urothelium, for the 53 chips in the human bladder microarray data set. Thus, for every homologous probe set, there were four different P values representing the significance level of the aforementioned tests. (We considered genes to be significantly differentially expressed if at least half of their corresponding probe sets are significantly differentially expressed in the same direction, unless there are other probe sets significantly differentially expressed in the opposite direction.) To gain more insight into the meaning of these nominal significance values, we additionally calculated the significance of the difference in expression for the remaining 21,873 probe sets on the HG-U133A chips for the four different comparisons described previously.

To determine whether the rodent homologs were enriched with genes significant to human disease progression, we used two similar statistical techniques. First, we performed a one-sided Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test to compare the P value distribution of the homologous probe sets to the P value distribution of all 22,215 probe sets found on the 53 HG-U133A chips profiling human bladder cancer tissue. To estimate false discovery rate (FDR) Q values for the KS tests, we performed the KS test on 1000 groups of randomly selected probe sets (with the same number of probe sets as in the groups of rodent homologs) to generate a distribution of random KS test P values. We then used the R package qvalue to estimate the Q value for the KS test involving the rodent homologs, using the 1000 random KS P values and the rodent homolog KS P value as input. We also used the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) program (version 2.0) [22–24] to test the rodent homologs for enrichment with significantly and differentially expressed probe sets in the 53 human samples categorized as previously mentioned, using the t test as the gene-ranking method, without collapsing the data set to gene symbols.

To determine whether the patterns of expression in rodent bladder tumors are more similar to those of invasive or noninvasive human cancers, we calculated human expression fold change values for each non-muscle-invasive or muscle-invasive tumor chip by dividing the expression value of an individual probe set by the average expression of all the normal urothelial chips for that probe set. We then generated a “mouse” or “rat” expression profile by assigning the fold change values (from the rodent normal vs tumor comparison) for a particular mouse or rat gene to all human probe sets homologous to that gene. We then performed hierarchical clustering analysis of the “rodent” profile and human tumor profiles. To improve the distinction between the clusters of non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive tumors, we only clustered probe sets with significant (P < .1) differences between non-muscleinvasive and muscle-invasive expression.

Results

Evaluation of Rodent Homologs as a Function of Malignancy

We first determined the human homologs of the rodent genes using NetAffx, as described in the Methods section; these are listed in Table W1. We found that the 90 originally published mouse genes correspond to 94 MG-U74Av2 probe sets and that the 145 originally published rat genes correspond to 173 Rat 230 2.0 probe sets. We subsequently found 144 unique human HG-U133A probe sets homologous to the 94 mouse probe sets and 223 unique human HG-U133A probe sets homologous to the 173 rat probe sets. Twenty-five human probe sets were homologous to genes that were differentially expressed in both rat and mouse. We were unable to find human probe sets homologous to nine mouse genes, and as mentioned in the Methods section, we ignored Plk-ps1 due to its pseudogenous nature; thus, analyses were performed on homologs of 80 mouse genes corresponding to 83 MG-U74Av2 probe sets. Similarly, we were unable to find human probe sets homologous to 35 rat genes; thus, analyses were performed on 110 rat genes corresponding to 138 Rat 230 2.0 probe sets.

We then examined how expression levels of rodent homologs changed according to human bladder state (normal, non-muscle-invasive, and muscle-invasive). After classifying the tissue samples into normal and malignant urothelium, we examined the differential expression between each pair of these three groups of tissues, using Student's t test. The numbers of probe sets and corresponding genes that were significantly (P < .05) differentially expressed between normal urothelium and urothelial carcinomas were computed. We found that 52 (65%) of 80 mouse homologs [86 (60%) of 144 probe sets] and 71 (63%) of 112 rat homologs [138 (62%) of 223 probe sets] were significantly differentially regulated between human normal urothelium and urothelial carcinoma (of any grade or stage). We further found that of 11 genes homologous among all three species, namely, human, rat, and mouse, 9 genes (82%), or 18 (72%) of 25 probe sets, were similarly differentially expressed.

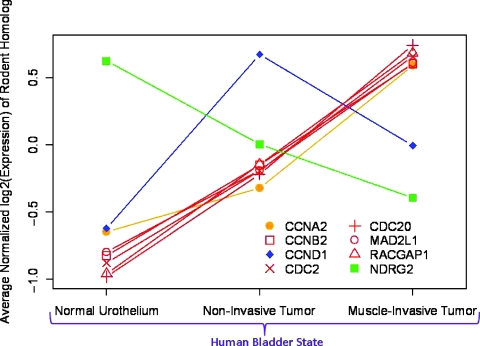

Identification of Interspecies Concordant Homologs in Transformation and Progression

In Figure 1B, we show the numbers of homologous genes that are significantly differentially expressed between normal and cancerous urothelium in all three species. Of 80 human homologs of the genes differentially expressed in mouse tumors, 55 genes were significantly differentially expressed in human (P < .05). However, of those 55 genes, only 31 were concordantly regulated; in other words, the direction of the change in expression in bladder tumors was the same in both species. Similarly, of 112 human homologs of the published rat genes, 74 were significantly differentially expressed in humans; 41 of these genes were concordantly regulated in both species. Few genes were differentially expressed and were concordantly regulated in all three species—seven genes were overexpressed and one was repressed. The patterns of gene expression for these eight genes (corresponding to the central regions in Figure 1B) are shown in Figure 2. Interestingly, for most of these genes, the expression level is correlated with invasiveness; NDRG2 is the sole gene to decrease expression with increasing invasiveness. Two genes (CCNA2 and CCND1) are significantly up-regulated only in invasive tumors (compared to noninvasive) and in noninvasive tumors (compared to invasive), respectively.

Figure 2.

Patterns of expression for genes differentially regulated in human, mouse, and rat bladder tumors as a function of human bladder state. The average normalized log2(gene expression) value for normal urothelium, non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive cancers are plotted for each tissue type. Data for all significantly and differentially expressed probe sets for the genes identified with an asterisk (*) in Figure 1B are plotted here. Line color codes relate to the gene expression pattern as a function of tumorigenicity and progression as shown in Table 2 (genes in bold). For example, genes with red lines are significantly differentially expressed between normal urothelium and noninvasive tumor and between noninvasive tumor and invasive human tumor.

To better understand the contribution of individual rodent homologs to human disease and progression, a similar analysis was performed for all rodent homologs. A complete list of human genes that are both homologous to and concordantly regulated with either mouse or rat is shown in Table 2. These genes are further classified according to different trends of significant differential expression with invasiveness. In Tables 3 and 4, these genes are listed as a function of the ontologies of the rodent homologs and indicate that genes associated with disease progression are associated with the cell cycle, transcription regulation, or the Ras and EGFR pathways.

Table 2.

Genes Differentially Regulated with Increasing Invasiveness in Human Bladder Cancer and Concordant in Expression with the Corresponding Rodent Homolog.

| Expression Pattern | Mouse Homologs | Rat Homologs |

| Positively correlated with transformation* and invasiveness | CCNB2, CDC2, CDC20, CKS1B, MAD2L1, NMI, RACGAP1, RAD51, TFDP1 | BUB1B, CCNB1, CCNB2, CDC2, CDC20, ECT2, MAD2L1, RACGAP1 |

| Negatively correlated with transformation invasiveness | N/A | N/A |

| Significantly increased in cancer, no significant change with invasiveness | CCNE1, PIK3CA, RAN, RHOG, RIN2 | DUSP6, PYCARD |

| Significantly decreased in cancer, no significant change with invasiveness | ARHGDIG, GATA4, MAP2K6, SH3BGR, SH3GL2, SH3GL3 | HRASLS, LGI1, PAK3, PPARA, WT1 |

| Significantly increased in non-muscle-invasive disease only | CCND1, MKNK1, RAD9A, SKAP2 | AKT1, ARHGAP8, BCL6, CCND1, IGFBP3, IGFBP4, NDRG4 |

| Significantly decreased in non-muscle-invasive disease only | GAS1 | CARD9, CDKN1C, FGFR2, FRS2, NTRK1, PDGFRL, RASA3, RORA, SNFT |

| Significantly increased in muscle-invasive disease only | CCNA2, CRELD2, FOXM1, MAP4K4, NFKBIE | CCNA2, CDCA3, CDKN2A, CDKN2C, CDKN3, KIF20A, MKI67, RAP2B |

| Significantly decreased in muscle-invasive disease only | GATA2, LMO1, NDRG2, SH2B1, TCF2, TCF21, TCF7L1 | CYP11A1, CYP3A43, FHIT, NDRG2, RAB27B, RORC |

Table 3.

Gene Ontology of Mouse Homologs Differentially Expressed between Normal Human Urothelium and Cancer, Listed in Table 2.

| Classification | Gene |

| Overexpressed in human muscle-invasive disease | |

| Cell cycle-related | CCNA2 (Ccna2), CCNB2 (Ccnb2), CCND1 (Ccnd1), CCNE1 (Ccne1), CDC2 (CDC2a), CDC20 (CDC20), CKS1B (Cks1), MAD2L1 (Mad2l1), TFDP1 (Dp1) |

| EGF/EGFR pathway | MAP4K4 (Map4k4), PIK3CA (Pik3ca), SKAP2 (Scap2) |

| Ras pathway | RACGAP1 (Racgap1), RAD51 (Rad51), RAD9A (Rad9), RAN (Rasl2.9), RHOG (Ahrg), RIN2 (Rin2) |

| Transcription regulators | CRELD2 (Etv6), FOXM1 (Foxm1), MKNK1 (Mknk1), NFKBIE (Nfkbie), NMI (Nmi) |

| Underexpressed in human muscle-invasive disease | |

| Cell cycle-related | GAS1 (Gas1) |

| MAPK/SRC pathway | MAP2K6 (Map2k6), SH2B1 (Sh2bpsm1), SH3BGR (Sh3bgr), SH3GL2 (Sh3gl2), SH3GL3 (Sh3gl3) |

| Ras pathway | ARHGDIG (Arhgdig) |

| Transcription regulators | GATA2 (Gata2), GATA4 (Gata4), LMO1 (Lmo1), NDRG2 (Ndr2), TCF2 (Tcf2), TCF21 (Tcf21), TCF7L1 (Tcf3) |

Table 4.

Gene Ontology of Rat Homologs Differentially Expressed between Normal Human Urothelium and Cancer, as Listed in Table 2.

| Classification | Gene |

| Overexpressed in human muscle-invasive disease | |

| Apoptosis | PYCARD (Pycard) |

| Cell cycle-related | CCNA2 (Ccna2), CCNB1 (Ccnb1), CCNB2 (Ccnb2), CCND1 (Ccnd1), CDC2 (Cdc2a), CDC20 (Cdc20), CDCA3 (Cdca3), CDKN2A (Cdkn2a), CDKN2C (Cdkn2c), CDKN3 (Cdkn3), DUSP6 (Dusp6), KIF20A (Cdc23), MAD2L1 (Mad2l1), MKI67 (Mki67) |

| Growth factors | IGFBP3 (Igfbp3), IGFBP4 (Igfbp4) |

| Oncogenes | ETC2 (Etc2), NDRG4 (Ndr4) |

| Small G-proteins | RACGAP1 (Racgap1), RAP2B (Rap2b) |

| Underexpressed in human muscle-invasive disease | |

| Apoptosis | NTRK1 (Ntrk1) |

| Cell cycle-related | CDKN1C (Cdkn1c), PPARA (Ppara), SNFT (Jundp1) |

| Growth factors | FGFR2 (FGFR2), FRS2 (BE112403), PDGFRL (BM384311) |

| Oncogenes | FHIT (Fhit), HRASLS (AI548958), NDRG2 (Ndrg2), PAK3 (Pak3), WT1 (Wt1) |

| Others | CYP11A1 (Cyp11a1), CYP3A43 (Cyp3a18), LGI1 (Lgi1), RORA (AI235414), RORC (BE110171) |

| Small G-proteins | RAB27B (Rab27b), RASA3 (Rasa3) |

Gene Enrichment Analysis Suggests Rodent Tumors Reflect the Molecular Profile of Human Cancer

To determine whether rodent homologs were significantly enriched with genes significant to human bladder cancer, we performed two separate but similar analyses. First, we applied the KS test to compare the distributions of t test P values between the rodent homologs and all 22,215 probe sets on the HG-U133A chips. We also used the GSEA program; because the GSEA program does not yet support testing gene sets with both up- and down-regulated genes, we split our gene sets into up- and down-regulated sets and ran the analysis for these split sets. The P values and FDR Q values for the KS tests and the GSEA tests are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Kolmogorov-Smirnov and GSEA P values and FDR Q values (in Parentheses) Showing the Significance of Enrichment of Sets of Rodent Homologous Genes with Probe Sets Significantly Differentially Expressed in Human Cancer.

| Normal vs Cancer | Normal vs Non-Muscle-Invasive | Normal vs Muscle-Invasive | Noninvasive vs Muscle-Invasive | ||||||

| KS | GSEA | KS | GSEA | KS | GSEA | KS | GSEA | ||

| Mouse | Down | 0.323 (0.989) | 0.0383 (0.0713) | 0.254 (1) | 0.0564 (0.109) | 0.151 (0.974) | 0.0998 (0.448) | 6 x 10-7 (0.0006) | 0 (0.00556) |

| Up | 0 (0.0824) | 0.008 (0.312) | 0.0183 (0.0947) | 0 (0.00972) | |||||

| Rat | Down | 0.896 (0.976) | 0.0476 (0.0564) | 0.320 (0.999) | 0.0269 (0.0576) | 0.769 (0.947) | 0.0646 (0.653) | 5 x 10-4 (0.114) | 0 (0.00478) |

| Up | 0.00963 (0.0649) | 0.0463 (0.154) | 0.00403 (0.0603) | 0 (0.00321) | |||||

| Intersection | Down | 0.047 (0.919) | 0.278 (0.273) | 0.484 (1) | 0.285 (0.325) | 0.028 (1) | 0.372 (0.701) | 2 x 10-4 (0.163) | 0.259 (0.323) |

| Up | 0.0286 (0.155) | 0.200 (0.227) | 0.0332 (0.0778) | 0.042 (0.141) | |||||

Numbers in bold represent statistically significant (FDR < 0.2) results.

The KS test results suggest that although the rodent homologs are not significantly associated with the initial development of human cancer, they are associated with the progression between non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive tumors. The results from GSEA tests are more complex: they support the KS test observation that rodent homologs are significantly associated with invasiveness, but the results also suggest that these genes are associated with the development of human tumors. (The small number of genes significantly down-regulated in all species may be the reason the down-regulated sets are not significantly enriched.) There are other significant findings as well; in particular, the rat homologs seem to be associated with the initial development of noninvasive human tumors. In general, it is clear that the rodent homologs are indeed relevant to human disease.

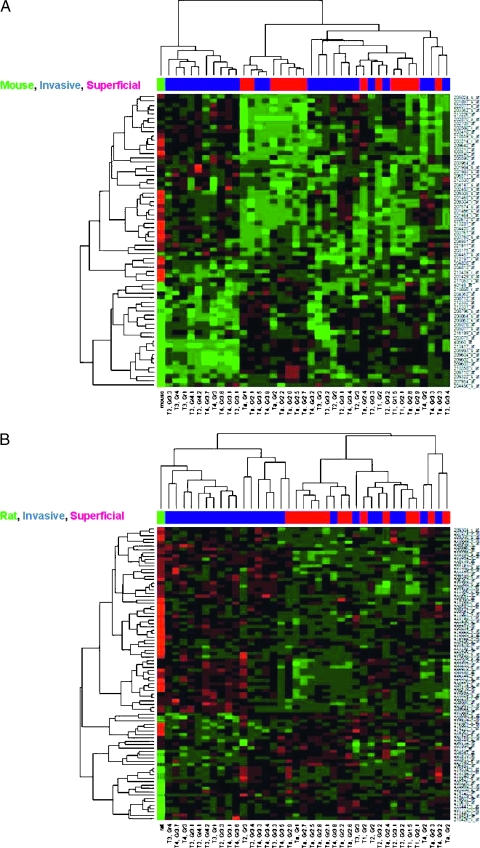

Rodent Tumors Have More Molecular Similarity to Invasive Rather Than Noninvasive Human Tumors

To determine whether these rodent models are more relevant for the study of noninvasive or invasive human disease, we performed unsupervised hierarchical clustering of expression fold changes between cancerous and normal tissues for the rodent homologs, where all probe sets homologous to a particular rodent gene are assigned the published fold change values [12,13] or the fold change as a function of tumor stage in the human samples (Table 1). The clusters for the mouse and rat homologs are shown in Figure 3, A and B, respectively. Figure 3A shows that the mouse homologs cluster into two main groups when human tumor stage data are used: one includes a mixture of non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive tumors, whereas the other is made up of exclusively muscle-invasive tumors. The “mouse” fold change profile derived from the rodent genes differentially expressed as a function of transformation clusters closely with this latter group, showing that the induced mouse tumors have a similar gene expression to a subset of human invasive tumors. Figure 3B shows the “rat” fold change profile clusters with most of the invasive human tumors. Together, these data suggest that rodent bladder tumors have gene expression profiles more similar to those of human invasive than noninvasive tumors and thus would be a better experimental model for the former.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering of rodent homologs with human cancer. Fold changes between gene expression values in human non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive tumors are hierarchically clustered with “mouse” (A) and “rat” (B) gene expression profiles. The probe sets in the “rodent” gene profiles are assigned published [12,13] fold change values (cancer vs normal) corresponding to the homologous rodent genes. Probe sets overexpressed in cancer are colored red, whereas underexpressed probe sets are colored green. HG-U133A probe sets are listed on the right, the stage and grade of the tumors characterized on the chips are shown on the bottom, and the color bar near the top of the figure represents the classification of the tumor: red indicates non-muscle-invasive tumors, blue indicates muscle-invasive tumors, and green indicates the mouse (A) or the rat profile (B).

Discussion

We have previously studied genes differentially regulated in metastatic human bladder cancer xenografts in mice to gain insight into regions of the chromosome involved in bladder cancer metastasis [25]. In this article, we study human homologs of rodent genes differentially expressed in chemical-induced animal models of bladder cancer. The comparison of evolutionarily conserved genes in different species is a frequently used technique-sequence alignments and comparative genomics analyses are often used to infer the function or evolutionary origin of a gene or protein, for example. Cross-species comparative expression profiling is relatively new, however, although it seems intuitive that genes with evolutionarily conserved sequences ought to have somewhat similar functions and should presumably be regulated in similar ways. Comparison of the tumor-related expression patterns of homologous genes in animal models of human cancers has been used to study the relevance of liver cancer in zebrafish to human liver [26], to evaluate seven different mouse models of hepatocellular carcinoma to find the most appropriate for liver cancer in humans [27], to compare a transgenic mouse model of lung cancer with a variety of human lung cancers [28], and to analyze several mouse models of breast cancer [29].

In the present study, we examined the patterns of gene expression involved in bladder cancer for three different species. Whereas others have studied a variety of animal models of human cancer [26–29] (including bladder [28]), here we focus on bladder cancer and compare the molecular profiles of carcinogen-induced rodent tumors with that of human disease. The carcinogenesis models are particularly relevant comparators and models because human bladder cancer is often a result of chemical carcinogenesis. Interestingly, we found that a significant proportion of rodent homologs exhibit significant differences in gene expression between non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive disease in humans. Furthermore, we determined that the induced rodent tumors exhibit more similarity of gene expression to human muscle-invasive disease than noninvasive disease, which is consistent with their muscle-invasive pathology.

Comparative genomic profiling across species can be divided into two steps: first, one determines whether genes important for a particular condition in one species are important in the other; second, one can determine the degree to which the patterns of gene expression are similar. We found that most human genes homologous to genes differentially expressed (vs normal) in bladder tumors in both mouse and rat were also significantly and differentially expressed (vs normal) in human tumors, suggesting that these homologous genes are indeed significant to human cancer. To quantify this with more statistical rigor, we performed KS and GSEA tests to examine the enrichment of significantly and differentially expressed genes among rodent homologs. We clearly found that these sets of human homologs were enriched with genes significantly differentially expressed between superficial and muscle-invasive bladder tumors. By focusing on genes that are consistently and concordantly expressed in bladder cancer in three species, we can be confident that such genes are robust candidates for proteins that are biologically important in human bladder carcinogenesis and progression.

Many of the genes differentially expressed between normal urothelium and urothelial cancer in all three species are associated with the cell cycle. For instance, cell division cycle 20 (CDC20), cell division cycle 2 (CDC2), cyclins D1 and B2 (CCND1 and CCNB2), mitotic arrest-deficient 2, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, homolog-like 1 (MAD2L1), and cyclin A2 (CCNA2) are all associated with progression through the cell cycle. CDC20 activates the anaphase-promoting complex [30], CCNB2 activates CDC2 [31], which promotes entry into metaphase [32,33], MAD2L1 is involved with the mitotic spindle checkpoint [34], and CCNA2 promotes entry into synthesis and metaphase [35]. Other genes differentially expressed in bladder tumors in all three species include RAC GTPase-activating protein 1 (RACGAP1), which deactivates RAC proteins and is overexpressed in tumors, and N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2), which is underexpressed in tumors. NDRG2 is a member of the NDRG family, of which NDRG1 is associated with apoptosis [36]. Furthermore, all, with the exception of NDRG2, are differentially expressed between non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive human tumors. These genes are overexpressed in muscle-invasive disease, with the exception of CCND1, which is underexpressed. Lindgren et al. [37] mentioned that CDC2, CCNB2, BUB1, and MAD2L1 are in a cell cycle- and mitosisrelated cluster of genes, which correlated expression with tumor progression. Blaveri et al. [38] said that CCNA2 and CDC2 were more highly expressed in a cluster of high-grade pTa and pT1 tumors than in a cluster of mainly low-grade pTa tumors, suggesting that the tumors in the first cluster were more aggressive. These corroborate our findings that the mouse and rat homologs are indeed important to bladder cancer.

Finally, through unsupervised hierarchical clustering of fold change profiles, we determined that rodent bladder tumors are closely associated with muscle-invasive human tumors. This suggests that such rodent tumors are good models for the mechanistic study of genes putatively involved in invasive and metastatic bladder cancer, especially those that are concordantly expressed in bladder cancer in three species.

In conclusion, this work suggests that carcinogen-induced rodent models of urothelial cancer share genetic similarities with pathways relevant to the development of muscle invasive human disease and provide genes that are candidate drivers or biomarkers of this process.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32DK069264 to P.D.W. and R01CA075115 to D.T.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, author. Cancer Facts and Figures 2008. Atlanta GA: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, Skinner E, Bochner B, Thangathurai D, Mikhail M, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe GR, Burch JD, Miller AB, Cook GM, Esteve J, Morrison B, Gordon P, Chambers LW, Fodor G, Winsor GM. Tobacco use, occupation, coffee, various nutrients, and bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980;64:701–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynder EL, Goldsmith R. The epidemiology of bladder cancer: a second look. Cancer. 1977;40:1246–1268. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197709)40:3<1246::aid-cncr2820400340>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole P, Hoover R, Friedell GH. Occupation and cancer of the lower urinary tract. Cancer. 1972;29:1250–1260. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197205)29:5<1250::aid-cncr2820290518>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matanoski GM, Elliott EA. Bladder cancer epidemiology. Epidemiol Rev. 1981;3:203–229. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, Koki AT, Leahy KM, Masferrer JL, Steele VE, Kelloff GJ, Hill DL, Seibert K. Celecoxib inhibits N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder cancers in male B6D2F1 mice and female Fischer-344 rats. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5599–5602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grubbs CJ, Moon RC, Squire RA, Farrow GM, Stinson SF, Goodman DG, Brown CC, Sporn MB. 13-cis-Retinoic acid: inhibition of bladder carcinogenesis induced in rats by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine. Science. 1977;198:743–744. doi: 10.1126/science.910158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Druckrey H, Preussmann R, Ivankovic S, Schmidt CH, Mennel HD, Stahl KW. Selective induction of bladder cancer in rats by dibutyl- and N-butyl-N-butanol(4)-nitrosamine. Z Krebsforsch. 1964;66:280–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukushima S, Hirose M, Tsuda H, Shirai T, Hirao K. Histological classification of urinary bladder cancers in rats induced by N-butyl-n-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine. Gann. 1976;67:81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kunze E, Schauer A, Schatt S. Stages of transformation in the development of N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine-induced transitional cell carcinomas in the urinary bladder of rats. Z Krebsforsch Klin Onkol Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1976;87:139–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00284372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao R, Lemon WJ, Wang Y, Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, You M. Altered gene expression profile in mouse bladder cancers induced by hydroxybutyl(butyl) nitrosamine. Neoplasia. 2004;6:569–577. doi: 10.1593/neo.04223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao R, Yi Y, Grubbs CJ, Lubet RA, You M. Gene expression profiling of chemically induced rat bladder tumors. Neoplasia. 2007;9:207–221. doi: 10.1593/neo.06814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Rudnev D, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Soboleva A, Tomashevsky M, Edgar R. NCBI GEO: mining tens of millions of expression profiles—database and tools update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D760–D765. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyrskjøt L, Kruhøffer M, Thykjaer T, Marcussen N, Jensen JL, Møller K, Ørntoft TF. Gene expression in the urinary bladder: a common carcinoma in situ gene expression signature exists disregarding histopathological classification. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4040–4048. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith SC, Oxford G, Baras AS, Owens C, Havaleshko D, Brautigan DL, Safo MK, Theodorescu D. Expression of ral GTPases, their effectors, and activators in human bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3803–3813. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu G, Loraine AE, Shigeta R, Cline M, Cheng J, Valmeekam V, Sun S, Kulp D, Siani-Rose MA. NetAffx: Affymetrix probesets and annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:82–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstrale M, Laurila E, et al. PGC-1α-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanian A, Kuehn H, Gould J, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. GSEAP: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3251–3253. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Siadaty MS, Riddick G, Frierson HF, Jr, Lee JK, Golden W, Knuutila S, Hampton GM, El-Rifai W, Theodorescu D. A novel method for gene expression mapping of metastatic competence in human bladder cancer. Neoplasia. 2006;8:181–189. doi: 10.1593/neo.05727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam SH, Wu YL, Vega VB, Miller LD, Spitsbergen J, Tong Y, Zhan H, Govindarajan KR, Lee S, Mathavan S, et al. Conservation of gene expression signatures between zebrafish and human liver tumors and tumor progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:73–75. doi: 10.1038/nbt1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, Calvisi DF, Heo J, Reddy JK, Thorgeirsson SS. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1306–1311. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sweet-Cordero A, Mukherjee S, Subramanian A, You H, Roix JJ, Ladd-Acosta C, Mesirov J, Golub TR, Jacks T. An oncogenic KRAS2 expression signature identified by cross-species gene-expression analysis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:48–55. doi: 10.1038/ng1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herschkowitz JI, Simin K, Weigman VJ, Mikaelian I, Usary J, Hu Z, Rasmussen KE, Jones LP, Assefnia S, Chandrasekharan S, et al. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang G, Yu H, Kirschner MW. Direct binding of CDC20 protein family members activates the anaphase-promoting complex in mitosis and G1. Mol Cell. 1998;2:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Labbe JC, Capony JP, Caput D, Cavadore JC, Derancourt J, Kaghad M, Lelias JM, Picard A, Doree M. MPF from starfish oocytes at first meiotic metaphase is a heterodimer containing one molecule of cdc2 and one molecule of cyclin B. EMBO J. 1989;8:3053–3058. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurse P, Bissett Y. Gene required in G1 for commitment to cell cycle and in G2 for control of mitosis in fission yeast. Nature. 1981;292:558–560. doi: 10.1038/292558a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nurse P, Thuriaux P. Regulatory genes controlling mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 1980;96:627–637. doi: 10.1093/genetics/96.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Y, Benezra R. Identification of a human mitotic checkpoint gene: hsMAD2. Science. 1996;274:246–248. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pagano M, Pepperkok R, Verde F, Ansorge W, Draetta G. Cyclin A is required at two points in the human cell cycle. EMBO J. 1992;11:961–971. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05135.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalaydjieva L, Gresham D, Gooding R, Heather L, Baas F, de Jonge R, Blechschmidt K, Angelicheva D, Chandler D, Worsley P, et al. N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 is mutated in hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy-Lom. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:47–58. doi: 10.1086/302978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindgren D, Liedberg F, Andersson A, Chebil G, Gudjonsson S, Borg A, Mansson W, Fioretos T, Hoglund M. Molecular characterization of early-stage bladder carcinomas by expression profiles, FGFR3 mutation status, and loss of 9q. Oncogene. 2006;25:2685–2696. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blaveri E, Simko JP, Korkola JE, Brewer JL, Baehner F, Mehta K, Devries S, Koppie T, Pejavar S, Carroll P, et al. Bladder cancer outcome and subtype classification by gene expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4044–4055. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.