Abstract

Objectives

Recruiting underserved women in breast cancer research studies remains a significant challenge. We present our experience attempting to locate and recruit minority and medically underserved women identified in a Nashville, Tennessee public hospital for a mammography follow-up study.

Study Design

The study design was a retrospective hospital based case-control study.

Methods

We identified 227 women (88 African American, 65 Caucasian, 36 other minority, 38 race undocumented in the medical record) who had undergone screening mammography and received an abnormal result during 2003–2004. Of the 227 women identified, 159 women were successfully located with implementation of a tracking protocol and more rigorous attempts to locate the women using online directory assistance and public record search engines. Women eligible for the study were invited to participate in a telephone research survey. Study completion was defined as fully finishing the telephone survey.

Results

An average of 4.6 telephone calls (range 1–19) and 2.7 months (range 1–490 days) were required to reach the 159 women contacted. Within three contact attempts, more cases were located than controls (61% cases vs. 49% controls, p=0.03). African-American women cases were four times likely to be recruited than African-American controls, (OR, 4.07; 95% CI, 1.59–10.30) (p=0.003). After three months of effort, we located 67% of African-American women, 63% of Caucasian women, and 56% of other minorities. Ultimately, after a maximum of 12 attempts to contact women, 77% of African-American women and 71% of Caucasian women were eventually found. Of these, 59% of African-American women, 69% Caucasian women, and 50% other minorities were located and completed the study survey for an overall response rate of 59%, 71%, and 47% respectively.

Conclusions

Data collection and study recruitment efforts were more challenging in racial and ethnic minorities. Continuing attempts to contact women may increase minority group study participation but does not guarantee retention or study completion.

Keywords: abnormal mammography follow-up, study recruitment, medically underserved females, case-control studies

Introduction

Adequate participation and retention are critical methodological issues in observational epidemiology[1] To insure a rigorous response rate for achieving generalizability and statistical associations, planning is necessary to estimate how many calls and letters will be needed to successfully locate and recruit the patient Recruitment barriers for enrolling medically underserved minorities into clinical trials research are well known and include, mistrust of the medical community, time, lack of race concordant investigators, length of questionnaires, fear of experimentation and lack of a mutual benefit for the minority patients to participate [2–10]. The recruitment barriers for clinical trials are not synonymous with barriers to recruit participants in observational research, which entails survey questionnaires and minimally invasive interventions. The suggested strategies to overcome recruitment for breast cancer screening observational studies have been noted as using community health or lay health workers[11] who are uniquely qualified to reach people missed by traditional health care systems, [12–13]. Community health workers that are enmeshed in the research investigator’s team have greater awareness of the breadth of research studies underway and can disseminate immediate opportunities for medically underserved patients to participate in research studies while simultaneously recruiting more diverse samples [14–15]. Another strategy is to incorporate a professional nurse as a patient navigator. Cancer patient navigation has been identified as a strategy to help overcome health care system barriers and facilitate timely access to quality medical and psychosocial care from screening through all phases of the cancer experience[16]. To counteract the historical barriers associated with clinical and pharmaceutical trials, other suggested strategies are specifying the patient’s level of commitment prior to study enrollment and addressing issues of exploitation and fear upfront [2–3].

The low participation and retention of medically underserved minority females in scientific research is troubling. Despite the increased rates of mammography screening in African-American women, they are still experiencing higher breast cancer mortality rates compared with Caucasian women (31.4 of 100,000 vs. 27.0 of 100,000, respectively)[17–18] and continue to have a lower-five year survival (75%) compared to Caucasian women (89%) [18]. Mammographic screening can enhance survival rates only if definitive diagnostic testing follows incomplete screening [19]. Due to under-utilization of mammography and delays in diagnostic evaluation compared to their counterparts, breast cancer appears at a later stage and a higher grade at diagnosis in minority women[20]. To identify why minority women are likely to miss follow-up diagnostic test appointments and to contribute to the improvement of health care services, the full participation of this population is necessary in observational epidemiology breast cancer studies[21].

Previous research has noted that additional time and effort is necessary to locate ethnic minorities[22]. Once located, recruiting this group in the study for data collection is also a challenge. Recently we completed an abnormal mammography follow-up study in a public hospital in Tennessee. The study questions targeted traditional breast cancer factors and psychosocial barriers that would affect delay or lack of diagnostic resolution of an abnormal mammography result.

This report is an analysis of the type and amount of effort required to locate and recruit women for their study-related telephone interviews. Our experiences may inform public health researchers to plan their efforts to locate and recruit individuals accordingly and identify why minority women who have low incomes and abnormal mammography findings are the most likely to miss follow-up diagnostic test appointments.

Methods

Setting and Sample

The Return after Mammography Study (RAMS)[23] was a hospital-based retrospective case control study in Davidson county, Nashville, Tennessee, conducted from 2003 to 2006. The study was designed to examine factors that affect minority and medically underserved women’s follow up of incomplete mammography testing. Eligible subjects were identified from a retrospective medical record review from a public hospital in Metropolitan Nashville. Mammography results were abstracted from the radiologist clinic notes in the medical records reports. Abnormal mammography was defined based on Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System® (BIRADS®) criteria developed by the American College of Radiology [24]. BIRADS criteria are 0= incomplete; needs additional imaging, 1=normal; 2=benign or stable abnormality, standard screening follow-up recommended; 3=probably benign abnormality, short term follow-up recommended; 4=suspicious abnormality, consider biopsy; 5=highly suggestive of malignancy. Due to the high prevalence of women who do not return for follow-up of incomplete mammography at this public hospital (25.8%), women with classifications of BIRADS-0 only were eligible for the study. Race/ethnicity status was obtained by the medical record and noted by the intake clerk at the breast center. In some instances, the race/ethnicity variable was missing and noted as undocumented prior to the breast center patient’s mammography screening appointment. We based our definition of follow-up and case-control status on previous findings where women with delays of 3 to 6 months between index abnormal mammogram findings and diagnostic resolution had 12% lower 5-year breast cancer survival rates than women with delays less than 3 months [OR= 1.47(95% CI 1.42–1.53)][25]. Study cases were defined as BIRADS-0 patients without diagnostic resolution in the ensuing 6 months after their index incomplete finding. Study controls were defined as BIRADS-0 patients with diagnostic resolution in the ensuing 6 months after their index incomplete finding.

The eligibility criteria for the study were as follows: (1) BIRADS-0 mammogram result requiring diagnostic follow-up prior to the next routine screening; (2) aged 40–75 years between January 2003- December 2004; (3) resident in an eight county radius of Nashville; and (4) able to provide informed consent. Women with a prior history of cancer, or who were too ill or hearing impaired at time of contact for interview were not eligible for the study.

Study procedures and recruitment

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Meharry Medical College prior to study implementation. All women eligible for the study had undergone the index BIRADS-0 mammogram at least 12 months prior to attempted contact The BIRADS-0 patients were identified as eligible from the medical records review and recruited for study participation. Eligible women were sent an introductory letter from the medical director of the breast health center (A.G.) inviting them to participate, explaining the study and informing women they would be reimbursed $15 for their time and effort. A toll free number was provided if the patients wanted to opt out and call for study refusal. The letter was mailed to the most recent address as listed on the medical record. The postal service ancillary service endorsement “Forwarding Service Requested” was written on the envelopes of the introductory letters to provide free forwarding of the letter to the patient’s most up to date address that may have been different from the address listed in the patient’s medical records. In many instances, patients had moved from their residences and the introductory letter was returned as undeliverable. If another address was obtained by the research staff, a second introductory letter was sent to the new address. Alternate addresses were also attempted when necessary including the emergency contact identified from the patient’s medical record and the billing system at the Nashville General Hospital.

The date that the study introductory letter was sent was recorded. The women were allowed 10 days to call the refusal line, assuming an interval of three business days for letter delivery. A call center unrelated to study staff and location was established to answer the refusal line so as to avoid potential coercion of study participants. Tacit consent for study participation was obtained if the woman did not call the refusal line within the 10 days.

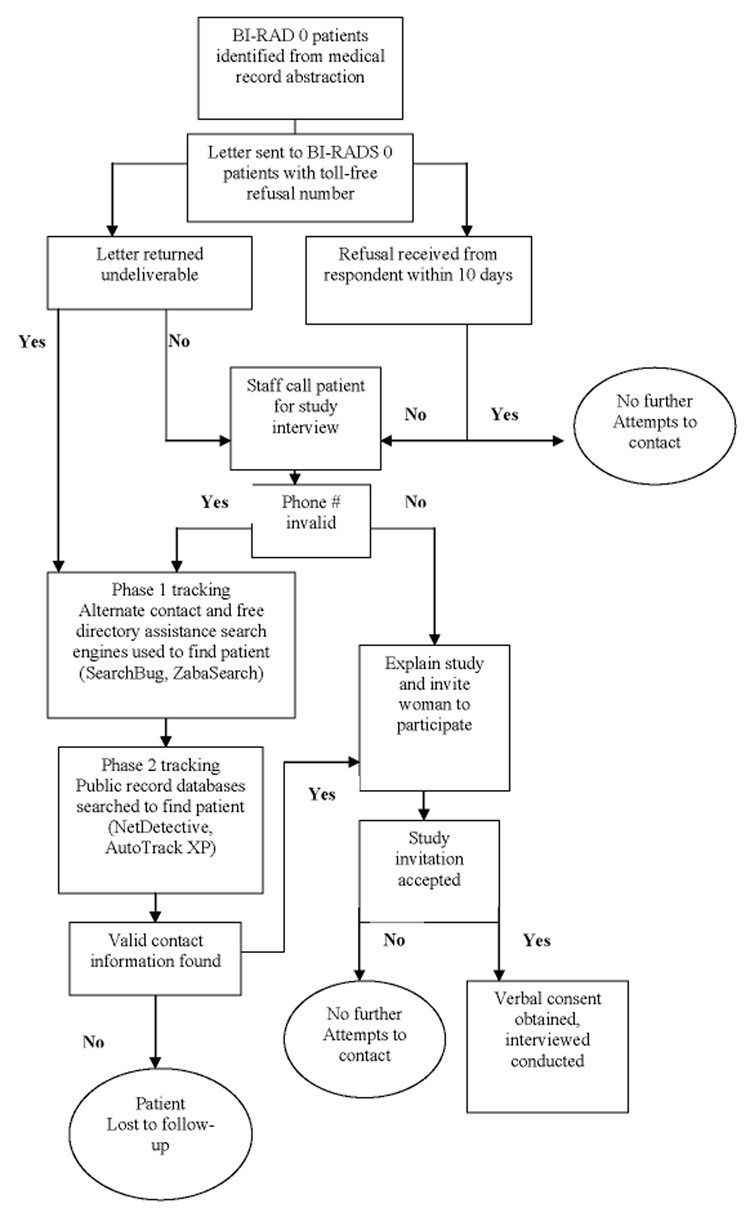

All patient contacts and interviews were completed by one full time trained research assistant, who completed a week training on psychosocial and epidemiologic data collection techniques: obtaining informed consent and HIPAA (Health Information Portability and Accountability Act) waivers over the phone, explaining study confidentiality, probing techniques, how to pose study questions without being leading or biased, data entry, and verbatim editing. The research assistant piloted these techniques through an epidemiologic survey instrument on 20 subjects. Upon contacting a potential participant, the research assistant explained the study and attempted to gain verbal consent for study participation. Those agreeing were mailed the study instrument survey scales, informed consent, HIPAA waiver, and a reimbursement form. The research assistant again contacted the patient by telephone 10 days after the date of the study materials were being mailed out. If the patient was reached on the first telephone call, the interview was administered after obtaining verbal consent. The patient also had the option of scheduling the survey interview during another telephone call. Each eligible patient was called at different times during the weekday and evening (up until 9 pm) and during the week end days and evenings as well. Up to 10 contact attempts were made following the above call schedule iteration until the patient was reached or there was evidence indicating she was not interested in participating (patient refusal, family member refusal for patient, patient did not speak English, patient sick or hearing disabled). At least 10 attempts at various time intervals were made for all valid phone numbers. After 10 call attempts a letter was sent to the woman asking her to contact the study team. If the woman called the study team as prompted by the letter, the iteration of telephone contacts continued beyond 10 attempts to “locate” the woman and invite her to participate in the study. Once all resources for an address and telephone number to contact the patient were exhausted, free directory assistance search engines were accessed (ZabaSearch, SearchBug, and Freeality). If no potential match was found or if the contact information proved to be invalid, online public record services (Net Detective, AutoTrackXP/ChoicePoint®) were purchased for tracking subject contact information. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Methods to recruit and deliver survey interview to participants for an abnormal mammography follow-up study in Tennessee, RAMS Study 2003–2006

Data Analysis

A patient was considered “located” if she agreed or refused to participate by phone, refused via the 1-800-refusal number, her family refused for her, or if she was hearing disabled or sick, and ineligibility was determined. “Not located” women were those that were lost to follow-up or did not respond to ≥ 10 contact attempts after her address had been confirmed. For each woman that was located, three variables were derived to indicate the amount of time (months of effort) that was needed to find her in intervals of 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months. Additionally, four variables were derived to indicate the level of effort (number of contact attempts) that were needed. The number of attempts to reach each woman was calculated to be ≤ 3 attempts, ≤ 6 attempts, ≤ 9 attempts, and ≤ 12 attempts.

We analyzed data stratified by age, race, income and educational attainment to examine if greater effort to locate and contact the patient resulted in success finding study respondents. We also were interested in the amount of effort to recruit the patient until study completion which is defined by participation in the survey telephone interview. Chi-squared or Fisher Exact test was performed to test for independence of location and recruitment for all categorical variables.

Results

A total of 227 women were identified who received a screening mammogram between January 2003 through December 2004 with an abnormal BIRADS-0 result were identified. Of these women, 127 had diagnostic resolution of the abnormal BIRADS-0 result within 6 months of the index mammogram (the ‘controls’) whereas the remaining 100 women had not (the ‘cases’). Among the 227 women 30% (n=68/227) were and not able to be contacted due to disconnected phones, changed phone numbers, changed addresses, or no answer from the telephone calls (n=27/227,11.9% cases, n=41/227, 18% controls). Of the 159 women who were located, 11% (n=18/159) were not eligible to participate in the study due to age, resident not residing in an eight county radius of Nashville, history of cancer or inability to provide consent and 2.5% (n=4/159) were deceased or too ill to participate. An additional 19% refused (n=17/159, 7.5% cases, n=24/159, 10.6% controls), and 11% partially completed the interview (n=13/159, 5.7% cases, n=11/159, 4.8% controls). A total of 76 interviews were achieved. The final sample for analysis included 35 cases and 41 controls, for an overall response rate including definitively eligible subjects of 54% among cases and 46% among controls. Of these, 59% (n=39) of African-American women, 69% (n=29) Caucasian women, and 50% (n=8) other ethnic minorities (women who had self-identified on the survey questionnaire as Spanish/Hispanic/Latino Mexican American/Puerto Rican/Cuban or Middle Eastern) were located and completed the study survey for an overall response rate of 71%, 59% and 47% (p= 0.197), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Final Dispositions of All Sampled for Phone Interviews RAMS study 2003–2006 (n=227 subjects)

| Description | Case n (%) | Control n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interview Complete | 35 (15.42) | 41 (18.06) | |

| Drop-out, Interview Partially Completed | 13 ( 5.73) | 11 ( 4.85) | |

| Refusals a | 17 ( 7.49) | 24 (10.57) | |

| Ineligible | 8 ( 3.52) | 10 ( 4.85) | |

| General | 2 | 0 | |

| Age ineligible | 0 | 1 | |

| Resident not in an eight county radius of Nashville | 1 | 2 | |

| Prior history of cancer | 0 | 2 | |

| Unable to provide informed consent | 0 | 1 | |

| Mental impairment | 0 | 1 | |

| Hearing impaired or sick | 1 | 1 | |

| Language barrier | 4 | 1 | |

| Respondent deceased | 0 | 1 | |

| Out of Scope b | 27 (11.89) | 41 (18.06) | |

| Total | 100 (44.05) | 127 (55.95) | |

| Response Ratesc by Case/Control and Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Case | Control | Total | |

| Caucasians | 66.67% | 73.08% | 70.73% |

| African Americans | 70.00% | 48.48% | 58.73% |

| Other d | 33.33% | 60.00% | 47.37% |

| Total | 53.90% | 46.10% | |

| p-value=0.1967 e | |||

Cases that are “Refusals” include refusal via the 1-800-refusenumber, family refusal, passive refusal and hostile/firm refusal.

Cases that are “Out of Scope” included no answer, busy signal, specific callback for study materials, general callback for study materials, answering machine message left, fax number, number changed, and phone disconnected.

The response rate was calculated by the number in the subgroup of “Interview Complete” divided by the number in the subgroups of “Interview Complete”, “Drop-out”, and “Refusals”.

Other: Hispanic/Latino or Middle Eastern ethnicity

Chi-squared test was performed for the response rates among racial/ethnic groups.

About 50% of women were reached by the third phone call and within 45 days. On average, it took 4.6 attempts (range 1–19 attempts) and 2.7 months (range 1 day to 1.3 years) to reach the women. Overall, 44% of the women were located within 30 days, 58% within 60 days, and 60% within 90 days.

Factors associated with successful contact of eligible women for the study were examined (Table 2). The results showed that medically underserved minority women required additional time and contact attempts to reach. After three months of effort, we had located 63% of Caucasian women, 67% African-American women and 56% of other minorities, (p=0.48). After maximum of 12 attempts, a total of 77% of African-American women and 71% of Caucasian women were ultimately located (p=0.30) (Table 2). Within three contact attempts, more cases were reached than controls (61% cases vs. 49% controls, p=0.03). To further investigate the race difference in study recruitment, logistic regressions were run for Caucasian, African-American, and other minorities separately. African-American women with "case" status were 4 times more likely to be recruited than African-American women with a "control" status (OR, 4.07; 95% CI ,1.59–10.30) (p =0.003)(Data not shown).

Table 2.

Cumulative Percentages of Women Located by the Days of Effort and Number of Contact Attempts by Characteristics at Mammography, RAMS study 2003–2006

| Days of Effort |

Number of Contact Attempts |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Number of women a | Percent contacted b | <= 30 | <=60 | <=90 | <=3 | <=6 | <=9 | <=12 |

| Overall | 227 | 70 | 44 | 58 | 60 | 53 | 67 | 69 | 69 |

| Age | |||||||||

| Less than 40 | 10 | 60 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 40<= age <50 | 112 | 64 | 41 | 54 | 57 | 48 | 61 | 63 | 63 |

| 50<= age <65 | 83 | 73 | 40 | 56 | 59 | 54 | 69 | 73 | 73 |

| 65+ | 14 | 93 | 71 | 86 | 86 | 79 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| p-value | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 65 | 71 | 42 | 58 | 63 | 49 | 68 | 71 | 71 |

| African American | 88 | 77 | 52 | 66 | 67 | 61 | 75 | 76 | 77 |

| Other c | 36 | 67 | 44 | 53 | 56 | 50 | 61 | 64 | 64 |

| p-value | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.30 | |

| Case/Control | |||||||||

| Case | 100 | 73 | 47 | 60 | 63 | 61 | 73 | 73 | 73 |

| Control | 127 | 68 | 41 | 56 | 57 | 49 | 61 | 66 | 67 |

| p-value | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.32 | |

unequal column totals reflect missing data.

percent located by end of study includes women requiring up to 490 days to locate and women requiring a maximum of 19 calls.

includes Hispanic/Latino or Middle Eastern ethnicity.

We also examined factors associated with participation among the women contacted (Table 3). Although 41 women refused to participate, only 29 women self-reported their race. The missing value for 'race' in medical record review was imputed with the valid response at phone interview completion. Of the 29 women with race identified who refused to participate, 52% (n=15) were African-Americans. Out of 24 women who agreed to participate but did not complete the interview or withdrew their consent, 58% (n=14) were African-Americans. Once African-American women were located they were willing to participate in the study. However, they had a higher refusal rate and a lower study completion rate than their Caucasian counterparts.

Table 3.

Frequency of interview completion status by demographic characteristics, RAMS study 2003–2006

| Interview status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women contacted a | Interview completed b | Interview not completed | Refused to participate | Ineligible | |

| Overall Case/Control | 159 | 76 | 24 | 41 | 18 |

| Control | 86 | 41 (47.7%) | 11 (12.8%) | 24 (27.9%) | 10 (11.6%) |

| Case | 73 | 35 (48.0%) | 13 (17.8%) | 17 (23.3%) | 8 (11.0%) |

| p-value | p=0.80 | ||||

| Age | |||||

| < 40 | 6 | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| 40 ≤ 50 | 72 | 35 (48.6%) | 16 (22.2%) | 15 (20.8%) | 6 (8.3%) |

| 50≤ 65 | 61 | 32 (52.5%) | 5 (8.2%) | 16 (26.2%) | 8 (13.1%) |

| < 65 | 13 | 6 (46.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| p-value | p=0.13 | ||||

| Race | |||||

| White | 46 | 29 (63.0%) | 2 (4.4%) | 10 (21.7%) | 5 (10.9%) |

| African-American | 68 | 37 (54.4%) | 11 (16.2%) | 15 (22.1%) | 5 (7.4%) |

| Other c | 24 | 9 (37.5%) | 6 (25.0%) | 4 (16.7%) | 5 (20.8%) |

p-value p=0.10

unequal column totals reflect missing data.

The chi-square or Fisher exact test was used to test for differences according to completion of full interview.

includes Hispanic/Latino or Middle Eastern ethnicity

Discussion

The results reported here are relevant to research studies that are recruiting medically underserved minority women as their target group. Our first significant finding is that locating medically underserved minority women for study enrollment may require a substantial commitment of time to yield positive results. On average it took 82 days and 4.6 attempts to reach each woman in our sample. To reach the majority of the women it took more than 3 months of effort and more than 12 phone calls. This finding is consistent with other studies that found a direct association between level of contact effort and the number of women contacted [22]. For example, in a group of 2,300 low-income minority women on a CDC funded mammography rescreening study, 32% of the women were located after 1 month of effort and 84% after more than 6 months effort.

The second significant finding is that locating medically underserved minority women requires extra time and effort. If we had stopped our contact efforts at 3 months of effort we would have located only 67% of African-Americans and 56% of those in the “other” race category. This finding is also substantiated in the literature [22,26].

A third observation is that extra attempts to contact and locate medically underserved minority women may be worthwhile, but study retention and completion efforts were not as successful. The majority of African-American participants (58%) did not complete the study or refused to participate once located (52%). These findings contradicted previous research where minority groups are willing to participate in non-invasive health research,[26–29] which our study represented by a one time 45 minute phone interview on mammography follow-up, without clinic visits or biospecimen collection. We also used a recommended strategy to maximize retention of the minority participants in the study of hiring an ethnic minority female to conduct interviews; however, she was not of African-American descent. In a previous epidemiologic case-control study of breast cancer, African-American women were less likely to complete the interview when they were invited to complete the survey by a non-African-American interviewer[30]. Since this study was conducted by a telephone interview, it is difficult to make conclusions about the relevance of the race of the interviewer to the study results. Additional research is needed to determine whether race or ethnicity concordance of a telephone interviewer has an effect on decisions to participate in cancer research among ethnic and minority groups[8,10].

Strengths and weaknesses/future research directions

This study has several methodologic weaknesses that should be taken into consideration when planning future research. Previous research asserts that the structure of the study must be designed in a way that is feasible for potential minority and medically underserved participants to complete. A direct association has been observed between study attrition of racial and ethnic minorities as the complexity of study participation increased. For example, studies that entail periodic clinic visits for collection of fasting blood draws limit participation due to barriers of time constraints and job inflexibility versus completing a telephone interview about breast cancer risk factors and mammography follow-up[31]. Although we tried to minimize barriers to participation in the survey research by using the telephone and postal service, the length of the questionnaire (166 items) was structured to administer in one telephone session and may have resulted in a response burden[7]. In retrospect, we should have thoroughly informed participants of the length of the questionnaire and the potential time burden as well as insured that they clearly understood the level of commitment required to participate in an observational study. By providing information on the nature of observational studies, we could have increased the knowledge base for the participants which may have improved their motivation to participate. Limited research has been performed on successful use of the telephone in cancer screening interventions. The telephone intervention types that have shown surpassing significance of response are multi strategy interventions types that include both individual directed one-on-one counseling as well as access-enhancing interventions[32]. More women who received tailored telephone counseling interventions that included information on breast cancer screening were more likely to engage in cancer prevention behavior as opposed to women who were in the control group.[33] Access-enhancing interventions may help give cues to the increase of cancer screening behavior including mammography use by study participants[32].

Lastly, this was a case-control study with one interaction with the participant and we did not provide informative feedback on how study participation could benefit them. Previous research shows receipt of information about cancer and how to prevent it allows subjects to make informed choices about their health. Feedback in the form of study results is deemed important for keeping participants involved and updated about progress and allaying distrust of researchers[34]. Qualitative studies on participation of African-American patients in observational epidemiologic cancer research cite crediting the participation of minority subjects as valuable at every phase of the study as essential for retention[3].

Our strengths are that we implemented a rigorous tracking protocol to locate and eventually recruit an underserved and hard to reach population of patients. Our findings show there is a direct association between the time and effort spent locating those “case” patients who have not returned for diagnostic services in 6 months and successfully recruiting them on study. We were able to support the breast center clinical staff clinical staff that do not have the resources at hand to make increased number calls and contacts to locate patients who do not respond to their results letter and return for mammography follow-up. Recruitment of medically underserved patients into hospital-based mammography follow-up studies has been a previously understudied area of research.

In summary, the results of this study suggest that when planning an observational epidemiologic study, investing study staff time and resources into contacting patients is initially valuable for medically underserved women’s participation but not sufficient for study retention and complete data collection. One overlooked resource for planning an epidemiologic study is consulting participants who have successfully engaged in and completed previous epidemiologic study protocols[3]. Study participants can serve as sounding boards during a study’s conceptualization, design, implementation, and interpretation phases. Study participants have an innate personal knowledge of research procedures that investigators can benefit from as participant weighs a study’s risks, benefits, and ethical considerations. Additional recruitment methods that have had some effect in minority population eligible for clinical trials include media campaigns, use of same race recruiters, and church-based recruitment projects with enhanced letters and phone calls. Observational studies investigating the most efficacious recruitment settings ( public hospitals, community health centers, churches, beauty salons, community health fairs, social and civic groups, or home health parties)[15,35] and strategies (in-person, recruitment letters, telephone calls, monetary incentives)[19] for identifying potential participants are needed. In addition, intervention studies that compare the effectiveness of different recruitment methods and strategies would provide valuable information to researchers on decisions that influence study retention. Community health workers are one such modality to encourage patients in underserved communities to make appropriate use of cancer detection services, whether screening or follow-up[12]. Efficacious and evidenced-based strategies are needed to increase recruitment and retention of patients at public hospitals who do not follow-up on abnormal mammography and experience disparities in breast cancer incidence, cancer mortality, survival and other cancer care[36–37]. A symbiotic working relationship between researchers and community health workers that have well-established working relationships with minority communities’ leaders and members may be a viable option for overcoming some of the barriers that have been encountered in recruiting underserved populations to breast cancer screening research. Merging the efforts of community health educators and community health education settings; such as churches and community health fairs may maximize scientific researchers’ efforts to recruit diverse samples to their research studies. Future research should examine reasons why women refuse to participate in epidemiologic survey research as well as obstacles to retention of a patient population of medically underserved and ethnic and racial minorities in these studies. Inclusion of minority and medically underserved women in observational epidemiologic studies is a vital component of addressing cancer health disparities and contributing to the improvement of cancer-related outcomes for this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the RAMS interviewers and participants for their support of this study.

Research funded by the National Cancer Institute U54 CA915408-04, Dr. Fair funded by the ACS grant number MRSGT-07-008-01-CPHPS, the Clinical Research Center of Meharry Medical College, Grant P20RR011792 from the National Institutes of Health and RCMI Clinical Research Infrastructure Initiative, National Cancer Institute U54 CA915408-06 and NIH Grant 5 P20 MD000516-03 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Types of epidemiologic studies. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, editors. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green BL, Partridge EE, Fouad MN, et al. African-American attitudes regarding cancer clinical trials and research studies: results from focus groups methodology. Ethn Dis. 2000;10(1):76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gooden KM, Carter-Edwards L, Hoyo C, et al. Perceptions of participation in an observational epidemiologic study of cancer among African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khaliq K, Gross M, Thyagarajan B, et al. What motivates minorities to participate in research? Minn Med. 2003;86:39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson GM, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1747–1759. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herring P, Montgomery S, Yancey AK, Williams D, Fraser G. Understanding the challenges in recruiting Blacks to a longitudinal cohort study: the Adventist health study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:423–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Killien M, Bigby JA, Champion V, et al. Involving minority and underrepresented women in clinical trials. J Women Health. 2000;9:1061–1070. doi: 10.1089/152460900445974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BeLue R, Taylor-Richardson KD, Lin J, Rivera AT, Grandison D. African Americans and participation in clinical trials: Differences in beliefs and attitudes by gender. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes C, Peterson SK, Ramirez A, et al. Minority recruitment in hereditary breast cancer research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13(7):1146–1155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenthal EL. A Summary of the National Community Health Advisor Study. Baltimore, MD: Anne E. Casey Foundation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: an integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002 January;19(1):11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margolis KL, Lurie N, McGovern PG, Tyrrell M, Slater JS. Increasing breast and cervical cancer screening in low-income women. J Gen Intern Med. 1998 August;13(8):515–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadler GR, Peterson M, Wasserman L, et al. Recruiting research participants at community education sites. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(4):235–239. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2004_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadler GR, York C, Madlensky L, et al. Health Parties for African American Study Recruitment. Journal of Cancer Education. 2006;21:71–76. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2102_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population: a patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2006 doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures, 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Healthy people 2010: With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2000

- 20.Allen B, Jr, Bastani R, Bazargan S, Leonard E. Assessing screening mammography utilization in an urban area. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(8):541–553. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-8-200604180-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. The unequal burden of cancer: an assessment of NIH research and programs for ethnic minorities and the medically underserved. National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobo JK, Shapiro JA, Brustrom J. Efforts to locate low-income women for a study on mammography rescreening: implications for public health practice. J Comm Health. 2006;31(3):249–261. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-9006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malin AS, Wujcik D, Grau A, Zheng W, Egan K. Delayed resolution of incomplete mammograms in the public hospital setting. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(11):1850S. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Radiology (ACR) Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System Atlas (BI-RADS® Atlas) Reston, Va: © American College of Radiology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given B. Relationship of caregiver reactions and depression to cancer patients' symptoms, functional states and depression--a longitudinal view. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:837–846. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00249-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senturia Y, Mortimer K, Baker D, et al. Successful techniques for retention of study participants in an inner-city population. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:544–554. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(98)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown DR, Topcu M. Willingness to participate in clinical treatment research among older African Americans and whites. Gerontologist. 2003;43:62–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLOS Med. 2006;3(2):e19, 201–210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, et al. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moorman PG, Newman B, Millikan RC, Tse CK, Sandler DP. Participation rates in a case-control study: the impact of age and race of interviewer. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:188–195. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipkus IM, Iden D, Terrenoire J, Feaganes JR. Relationship among breast cancer concern, risk perceptions, and interest in genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility among African-American women with and without a family history of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:533–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legler J, Meissner HI, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 January;11(1):59–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen B, Jr, Bazargan-Hejazi S. Evaluating a tailored intervention to increase screening mammography in an urban area. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 October;97(10):1350–1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenfant C. Enhancing minority participation in research The NHLBI experience. Circulation. 1995;92:279–280. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai GY, Gary TL, Tilburt J, et al. Effectiveness of strategies to recruit underrepresented populations into cancer clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2006;3:133–141. doi: 10.1191/1740774506cn143oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:78–93. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]