Abstract

Deposition of insoluble amyloid plaques is frequently associated with a large variety of neurodegenerative diseases. However, data collected in the last decade have suggested that the neurotoxic action is exerted by prefibrillar, soluble assemblies of amyloid-forming proteins and peptides. The scarcity of structural data available for both amyloid-like fibrils and soluble oligomers is a major limitation for the definition of the molecular mechanisms linked to the onset of these diseases. Recently, the structural characterization of GNNQQNY and other peptides has shown a general feature of amyloid-like fibers, the so-called steric zipper motif. However, very little is known still about the prefibrillar oligomeric forms. By using replica exchange molecular dynamics we carried out extensive analyses of the properties of several small and medium GNNQQNY aggregates arranged through the steric zipper motif. Our data show that the assembly formed by two sheets, each made of two strands, arranged as in the crystalline states are highly unstable. Conformational free energy surfaces indicate that the instability of the model can be ascribed to the high reactivity of edge backbone hydrogen bonding donors/acceptors. On the other hand, data on larger models show that steric zipper interactions may keep small oligomeric forms in a stable state. These models simultaneously display two peculiar structural motifs: a tightly packed steric zipper interface and a large number of potentially reactive exposed strands. The presence of highly reactive groups on these assemblies likely generates two distinct evolutions. On one side the reactive groups quickly lead, through self-association, to the formation of ordered fibrils, on the other they may interfere with several cellular components thereby generating toxic effects. In this scenario, fiber formation propensity and toxicity of oligomeric states are two different manifestations of the same property: the hyper-reactivity of the exposed strands.

INTRODUCTION

Neurodegenerative diseases are pervasive pathologies characterized by severe neuronal damage (1). These frequent diseases include Alzheimer and Parkinson disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, motor neuron diseases, and the large group of polyglutamine disorders. Deposition of insoluble amyloid plaques is often associated with a large variety of neurodegenerative disorders. For several years, it has been assumed that amyloid aggregates were directly linked to the onset of the pathologies. Over the past decade, data derived from several independent investigations suggest that prefibrillar, diffusible assemblies of amyloid-forming proteins and peptides are the most harmful species (2–5). It has been shown that only a weak correlation between the severity of these diseases and the density of fibrillar amyloid plaques exists. On the other hand, better correlations have been found between the progression of the disease and the presence of oligomeric aggregates.

Enormous efforts are being made to bypass a phenomenological description of neurodegenerative diseases. However, dissecting the molecular basis of these processes is generally hampered by several factors. One of the major limitations is the paucity of structural data available for both amyloid-like fibrils and soluble oligomers. Indeed, the insoluble nature of the former and the transient nature of the latter have hitherto prevented straightforward structural analyses. Nevertheless, characterizations of different models have provided insightful information on plausible basic features of fibril core structure (6–14). Among these, the peptide GNNQQNY from the yeast prion protein Sup35 deserves a special position (15). Extensive analyses have shown that this peptide forms fibers that exhibit all of the common features of amyloid fibrils (unbranched morphology; cross-β diffraction pattern; binding of Congo red; lag-dependent cooperative kinetics of formation, and unusual stability) (16). Furthermore, the elucidation of GNNQQNY 3D-structure, which is characterized by a cross-β-spine steric zipper motif, has shown some general structural features of amyloid-like fibers at atomic level (16). Subsequent molecular dynamics (MD) and NMR investigations have provided further insights into the structure and stability of this unique motif (17–21). Moreover, a very recent research on yeast prion Sup35 strains provided evidence that steric zipper association is likely the scaffold structure of the core of Sup35 fibrils (22).

By using replica exchange MD (REMD), an advanced methodology for enhancing conformational sampling (23), we carried out an extensive analysis of the properties of several GNNQQNY aggregates with different sizes. The analysis of small-size models has provided information on the structural properties of possible intermediate states along the fiber formation process. Present data give what we believe are new insights into the structural basis of amyloid oligomer formation and toxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

System setup

Several MD simulations have been carried out on different GNNQQNY aggregates with increasing dimensions. The starting coordinates for the MD simulations were derived from the crystal structure of the peptide GNNQQNY (Protein Data Bank (24) code 1YJP) (15). Double β-sheet models, with a number of strands ranging from 2 to 5, were considered (see Table 1 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material, Data S1). These starting models were built by using the symmetry operations of GNNQQNY structure space group (P21).

TABLE 1.

Sampling statistics

| System | Average exchange frequency (%) | Atoms (n) | Water molecules (n) | Strands (n) | Simulated time (per replica) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SH2-ST2 | 25.456 | 8465 | 2711 | 2 + 2 | 80 ns + 80 ns |

| SH2-ST3 | 25.909 | 8478 | 2660 | 3 + 3 | 10 ns |

| SH2-ST4 | 26.489 | 8494 | 2610 | 4 + 4 | 10 ns |

| SH2-ST5 | 26.240 | 8492 | 2554 | 5 + 5 | 10 ns |

| SH2-ST2/3 | 25.189 | 8515 | 2700 | 2 + 3 | 80 ns + 80 ns |

The various models of GNNQQNY aggregates were immersed in a box filled with extended single point charge (SPCE) waters (25) and periodic boundary conditions were applied. After an initial energy minimization, a water equilibration procedure has been applied. All analyses, unless otherwise specified, were carried out on the equilibrated region of the trajectories.

Replica exchange molecular dynamics

Simulations were carried out with the GROMACS (26) package by using GROMOS96 force field with an integration time step of 2 fs, following the procedure adopted for REMD simulations on prion protein (27). Nonbonded interactions were accounted by using the particle mesh Ewald method (grid spacing 0.12 nm) (28) for the electrostatic contribution and cut-off distances of 1.4 nm for Van der Waals terms.

REMD protocol includes several replicas of the system evolving independently at different temperatures (T). Exchanges between neighboring replicas are attempted every tswap on the basis of the Metropolis criterion (Eq. 1):

|

(1) |

where  is the exchange probability, KB is Boltzmann's constant, U1 and U2 are the instantaneous potential energies and T1 and T2 are the reference temperatures. Because Eq. 1 is suited in the NVT ensemble, an additional term for the isobaric-isothermal (NPT) ensemble, adopted here, should be introduced (23). This term is, however, negligible when the volumetric fluctuations are small (29), as in the case of an all-atom simulation.

is the exchange probability, KB is Boltzmann's constant, U1 and U2 are the instantaneous potential energies and T1 and T2 are the reference temperatures. Because Eq. 1 is suited in the NVT ensemble, an additional term for the isobaric-isothermal (NPT) ensemble, adopted here, should be introduced (23). This term is, however, negligible when the volumetric fluctuations are small (29), as in the case of an all-atom simulation.

The REMD samplings for all systems were composed of 16 replicas ranging from 300 K to 348 K. The temperatures have been selected for ensuring homogeneous exchange frequencies between replicas. These are: 300.0, 303.0, 306.0, 309.0, 312.1, 315.2, 318.3, 321.5, 324.7, 327.9, 331.2, 334.5, 337.8, 341.1, 344.4, and 348.0. To achieve consistent exchange frequencies among the various samplings carried out, the same temperature pattern and comparable systems dimensions (Table 1) have been adopted. Initially, for all of the systems analyzed, the simulation time was 10 ns per each replica. As a result, for each system a total sampling of 160 (10 ns × 16) ns was carried out. Later, to further increase the sampling for the SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3 systems, the simulations were extended up to 80 ns per replica (total time, 1.28 μs) (Table 1). Moreover, to assess the robustness of the samplings, a second set of 80 ns per replica were carried out for the SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3 systems. The second samplings were carried out by using slightly different initial conformations. In particular, the RMSDs from the starting structures of the first run were 1.26 Å and 1.74 Å for SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3, respectively.

In all simulations, the minimum distance between the system and its images generated by the periodic boundary conditions was always larger than the cut-off values used for nonbonded interactions.

Reaction coordinates and free energy projections

The analysis of the REMD data has been carried out by selecting appropriate reaction coordinates. The distances of facing Cα-Cα atoms of opposing strands in the steric zipper motif can be clustered as short (≈7 Å) and long (≈10.5 Å), whose average gives the experimentally observed 8.5–9.0 Å spacing reported for this structural motif. In this analyses, distances of facing Cα-Cα atoms of the inner residues of each strand were considered to build the reaction coordinates. In particular, the projection D1 is the average of the Cα-Cα distance between the pairs N3-Q5 (starting distance d = 10.6 Å), Q4-Q4 (d = 6.9 Å), and Q5-N3 (d = 10.4 Å) (Fig. 1). To balance the impact of short and large distances, the weight of the two long distances (N3-Q5 and Q5-N3) in the average was 0.5. As a consequence, the starting value of D1 is 8.69 Å, a value that closely resembles the spacing of the pair of sheets. The projection D2 is equivalent to D1, but it refers to an adjacent couple of facing strands (Fig. 1). Free energy projections were calculated from the histogram distribution of the populations by applying Boltzmann equation. In addition, to extract free energy projections at a given temperature, we also used the method denoted as temperature derivation of the weighted histogram analysis method (T-WHAM) (see the Supplementary Material, Data S1, for further details and Gallicchio et al. (30)).

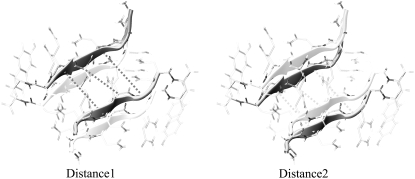

FIGURE 1.

Reaction coordinates as function of distances between facing strands. The coordinate is calculated by averaging Cα-Cα distances between facing residues N3-Q5, Q4-Q4, and Q5-N3. Because Cα-Cα distances can be clustered as short (≈7 Å) and long (≈10.5 Å), we assign a weight of 0.5 to the long N3-Q5 and Q5-N3 and a weight of 1 to the short Q4-Q4. For assemblies composed of more than four strands, edge strands are considered.

Free energy perturbation

The free energy perturbation was calculated from a state A (representative of the double sheeted steric-zipper) to a state B (representative of the two dissociated single sheets). The perturbation of the Hamiltonian (H) is carried out by formulating H as a function of a coupling parameter λ: H = H (p, q; λ) in such a way that λ = 0 describes system A and λ = 1 describes system B:

|

(1a) |

where p and q represent the Cartesian coordinates and conjugate momenta, respectively. In this calculation, both D1 and D2 reaction coordinates (as defined above) have been perturbed from a value of 8.69 Å in the state A (corresponding to the steric zipper) to a value of 28.69 Å (corresponding to a state where the two sheets composing the original steric zipper are separated and do not see each other). The calculation has been made alternating a “sampling step” where  is evaluated at constant λ (sampling time in each point = 2 ns) and a “moving phase,” where λ increases linearly from a sampling point to another (the overall moving phase from λ = 0 to λ = 1 extends for 10 ns). In each sampling point, the derivative of the free energy with respect to λ is evaluated according to:

is evaluated at constant λ (sampling time in each point = 2 ns) and a “moving phase,” where λ increases linearly from a sampling point to another (the overall moving phase from λ = 0 to λ = 1 extends for 10 ns). In each sampling point, the derivative of the free energy with respect to λ is evaluated according to:

|

(2) |

where β is the inverse temperature (KBT)−1. Herein,  has been sampled in 16 points with λ = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.75, 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, and 1. Finally, the free energy difference is computed by integrating Eq. 2:

has been sampled in 16 points with λ = 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 0.25, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.75, 0.80, 0.85, 0.90, 0.95, and 1. Finally, the free energy difference is computed by integrating Eq. 2:

|

(3) |

RESULTS

Systems and overall REMD features

Replica exchange molecular dynamics simulations were conducted on a variety of different starting models assembled as steric zipper double layers (see Table 1, Fig. S1 in Data S1, and Materials and Methods). The number of strands considered ranged from 2 to 5. On analogy with our previous notation (19), each model has been denoted as SH2-STi, where “i” is the number of strands per sheet.

REMD technique allows for significantly enhanced sampling of conformations, due to frequent switching of simulation temperatures (31,32). High Ts enable the system to cross the energy barriers whereas low Ts allow for an efficient exploration of local minima. Herein, all runs have reported significant random walks in the temperature space consistent with very high exchange frequencies (∼25%) (Table 1; Fig. S2 A, Data S1) and considerable overlaps of the potential energy distributions (Fig. S3, Data S1). As a result, each replica explored the whole temperature space by passing repeatedly throughout all thermal baths (Fig. S2 B, Data S1).

Overall stability of the models SH2-ST3, SH2-ST4, and SH2-ST5

To analyze the massive sampling produced (5.6 μs in total) several free energy projections have been carried out. Because this study was focused on the factors determining the preservation/disruption of steric zipper motif, initial reaction coordinates were based on intersheet distances. Indeed, one of the distinctive features of this motif is the short intersheet distance (8.5–9.0 Å) arising from a tight interdigitation of side-chains (15). Accordingly, REMD conformations were projected on D1 and D2, which account for the separation distances of facing strands (Fig. 1).

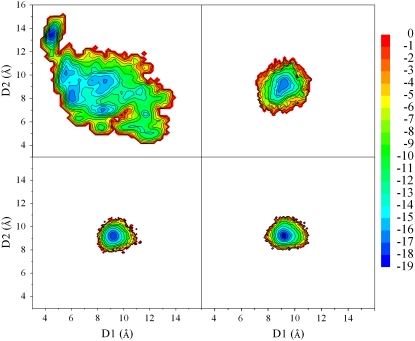

The comparison of free energies based on initial samplings (10 ns per replica) shows that the evolution of the starting structure depends on the size of the aggregates (Fig. 2). Larger assemblies (SH2-ST3, SH2-ST4, and SH2-ST5) show a single basin (Fig. 2, B–D) around the starting values of the reaction coordinates (D1, D2 = 8.5 ∼ 9 Å). This finding indicates that systems composed by at least six strands (SH2-ST3) are quite stable. Moreover, the basin size becomes sharper on increasing of the aggregate size. The stability of these models throughout the simulations has also been confirmed by the analysis of the geometric parameters (gyration radius, secondary structure, hydrogen bonding interactions, etc.) used routinely in MD investigations. We also focused on models composed of a single β-sheet. The analyses showed that these systems are rather stable in the timescale of 10 ns REMD simulation (data not shown). This is in line with the evolution of the system SH2-ST2 (see below).

FIGURE 2.

Conformational free energies of double layers of increasing size. D1-D2 projections calculated from the conformation of the basic sampling (10 ns, see Table 1). The energies are reported in kJ/mol. (A) SH2-ST2. (B) SH2-ST3. (C) SH2-ST4. (D) SH2-ST5.

Although stable in the timescale of the simulation, the β-sheets of the analyzed steric-zipper models adopt a significantly twisted structure during the REMD simulation, in line with previous investigations (19,21,33). As shown in Fig. S4, Data S1, for the model SH2-ST5, on overall twist of ∼40–44° is observed. This value is in line with previous analyses that estimated a twist of 10–11° (40–44° ÷ by 4) between consecutive strands (19). Fig. S4, Data S1, also shows that at 300 K a minor spreading of the overall twist angle is observed. Because this analysis has been carried out on the entire SH2-ST5, these data suggest that even edge β-strands have well-defined structure so that no fraying behavior is observed. While keeping the same most-populated state, the conformational spread increases at 348 K. This finding suggests that even steric zipper models with a moderate size are endowed with a remarkable stability. The shape of the population 2D distribution at 348 K suggests that the deformation of the overall twist angles of the two sheets from the standard ones (45°, 45°) are somewhat related. In other words, the steric zipper represents a strong structural constraint that transmits deformations from one sheet to the other. Similar effects were detected in the transition from the flat to the twisted states occurring in the initial stages of the simulation (Fig. S5, Data S1). In all cases, the twisting angles of the two sheets are highly correlated.

Conformational space of the SH2-ST2 model

A radically different picture emerges from the analysis of SH2-ST2 evolution in the simulations. Fig. 2 A indicates clearly that, along with a poorly populated starting state, several other conformational basins appear. The conformational versatility of the SH2-ST2 aggregate prompted us to extend the simulation up to 80 ns per replica to increase the conformational sampling.

The free energy calculated from the 80 ns REMD sampling (Fig. 3 A) shows the existence of well-defined conformational basins, along with fluctuating less-stable aggregates. Interestingly, the starting state does not fall in any of the most populated basins. This suggests that steric zipper interactions are not able to keep the two facing sheets of the SH2-ST2 model in a stable state. The same overall picture emerges from the analysis of the free energy projections derived by using the T-WHAM (Fig. S6 A, Data S1). Notably, similar conformational states are populated in the projection at 348 K (Fig. S7, A and C, Data S1).

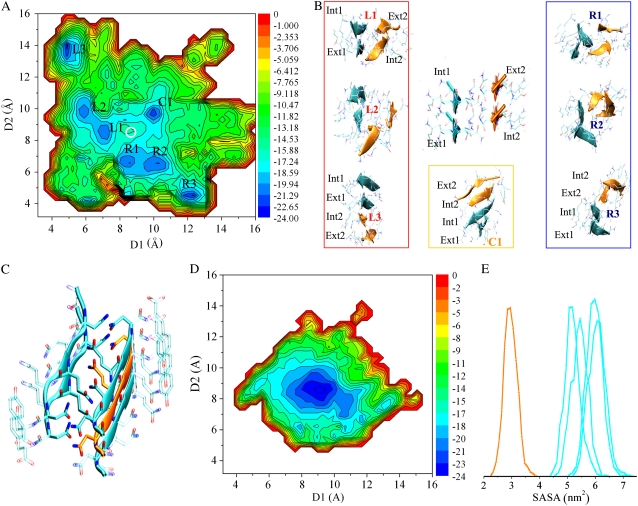

FIGURE 3.

Conformational rearrangement of SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3 during the simulation. (A) D1-D2 free energy projection calculated on 80 ns sampling of SH2-ST2. The energies are reported in kJ/mol. A white circle encloses the region corresponding to starting basin. The notation used to identify the most populated basins is also reported. (B) Some representative structures of the most populated basins. (C) The SH2-ST2/3 starting model. (D) D1-D2 free energy projection calculated on 80 ns sampling of SH2-ST2/3. The energies are reported in kJ/mol. (E) Distribution of solvent accessible area for the five strands of the SH2-ST2/3 structures belonging to most populated region of the diagram. The solvent accessible surface distribution of the internal strand is shown in orange.

Consistently with the structural equivalence of the two reaction coordinates, (D1 and D2) the energy projection exhibits symmetry along the D1-D2 diagonal (Fig. 3 A). This result is an indicator that an appropriate conformational sampling has been achieved in the 80 ns REMD simulation. The basins corresponding to the new conformational species emerged from the trajectory were denoted according to their position onto the diagram (Fig. 3 A). In particular, the equivalent states located either on the left or right side of the D1-D2 diagonal were denoted as L1-L2-L3 or R1-R2-R3, respectively. The only populated basin that falls on the D1-D2 diagonal has been denoted as C1.

Interestingly, the most populated basins (L3, R3, and C1) exhibit a common structural feature because all they include structures formed by a single four-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 3 B). The observed propensity of the strands of the SH2-ST2 model to associate in a single β-sheet, once the steric zipper motif is broken, is in line with a recent REMD analysis carried out on the dimer formation by GNNQQNY monomers that shows their high tendency to form β-sheets (34).

The single sheet structures of the C1 basin are characterized by an antiparallel coupling of the two initially facing sheets (Fig. 3 B). These structures form from the starting SH2-ST2 steric zipper model through a sliding process of one sheet over the other. The structures of the basins L3, and equivalently R3, correspond to an opening of the starting structure with the consequent association of two initially facing strands (Fig. 3 B). Indeed, for L1 conformers the initial D1 values of 8.69 Å (intersheet distance) reduces to ∼4.9 Å, which represent the typical main chain distance between consecutive strands in a sheet. An equivalent trend is observed for the coordinate D2 in the case of the R3 basin.

This picture is fully confirmed by a second independent REMD simulation (80 ns) carried out by using as starting model a conformation selected from the trajectory of the first simulation and showing a RMSD of 1.26 Å from the starting structure of the first run (Fig. S8 A, Data S1,and Materials and Methods).

Analysis of accessible area and hydrogen bonds of SH2-SH2 conformational states

In the starting SH2-ST2 structure every strand has one of its hydrogen-bonding faces exposed to solvent and the other one engaged in the β-sheet hydrogen bonds. However, the two strands in each sheet are not equivalently exposed, due to the vertical shift of the sheets relative to each other (21 screw axis). Indeed, the strands of each sheet can be classified as internal (int) or external (ext) (see Fig. 3 B for the notation). The difference of total solvent accessibility between int or ext strands is ∼750 Å2.

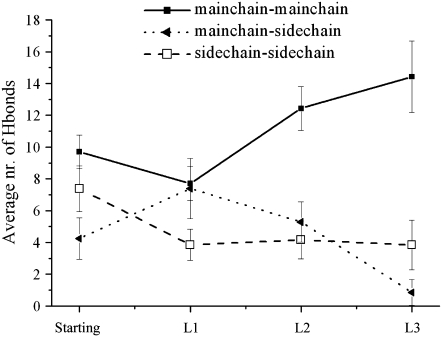

To gain insights into the structural features of the models emerged from the REMD simulations, the solvent accessible surface (SAS) of representative structures of the L1, L2, and L3 basins have been analyzed. The analysis was limited to these states because R1, R2, and R3 are symmetrically equivalent to L1, L2, and L3 and the models of C1 are similar to those found in L3 (both in single sheet conformation). Our analysis indicates that the L3 models show a significantly decreased main-chain solvent accessibility. This is due to the “covering” of two strands (int2 and ext1) in the formation of a single sheet (Fig. S9, Data S1). As expected, the analysis of the hydrogen bonds indicates that the L3 state, compared to the starting model, is characterized by an increased number of main-chain/main-chain hydrogen bonds, due to the formation of an additional strand-strand coupling, by a decreased number of hydrogen bonds involving side chains, due their increased flexibility on steric zipper opening (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Average number of hydrogen bonds of SH2-ST2 structures of L1, L2, and L3 basins compared to the one exhibited by the starting model. The SD for different classes of hydrogen bonds are also reported.

The conformational states of the basin L1, which are characterized by V-shaped structures (Fig. 3 B), retain most of the features of the starting model (Fig. 4 and Figs. S9–S11, Data S1). On the other hand, the models of the L2 basin, in which significantly H-bonds interactions between ext1 and int2 are observed, resemble the single sheet L3 states (Fig. 4 and Figs. S9–S11, Data S1).

Evolution of the double-sheet model SH2-ST2/3 during the simulation

The findings illustrated in the previous sections encouraged us to analyze the dynamic behavior of the asymmetric model composed of two sheets: one made of two and the other of three strands (SH2-ST2/3) (Fig. 3 C). For this system 80ns of REMD sampling were carried out. As shown in Fig. 3 D, this aggregate is rather stable in the timescale of the simulation. The stability within the sampling is also evidenced by the analysis of the solvent accessible area of the individual strands (Fig. 3 E). This finding suggests that the addition of a single strand (going from SH2-ST2 to SH2-ST2/3) is able to endow the GNNQQNY aggregates with a remarkable stability. It is worth noting that all side chains of SH2-ST2 strands are partially exposed to the solvent, whereas side chains of the central strand of the three-stranded sheet are completely buried (Fig. 3 C). Evidently, the larger intersheet surface and an increased number of interactions prevent the opening of the structure seen in SH2-ST2. This picture is fully confirmed by a second independent REMD simulation (80 ns) carried out by using as starting model a conformation selected from the trajectory of the first simulation with a RMSD of 1.74 Å from the starting structure of the first run (Fig. S8 B, Data S1, and Materials and Methods).

It is worth mentioning that the T-WHAM free energy projection at 300 K of the SH2ST2/3 highlights few additional low-populated states (Fig. S6 B, Data S1) somehow resembling the structural features of L1 and L2 in SH2ST2. At high temperature (348 K) the population of some of these states is more significant and it is comparable to that of the steric-zipper conformers (Fig. S7, B and D, Data S1).

Finally, to estimate the dissociation free energies of SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3, we computed the free energy perturbation from a state representative of the double sheet steric-zipper motif to a state representative of the two dissociated single sheets (Fig. S12, Data S1). The analysis of the resulting energies indicates that the addition of a single, fully buried, strand doubles the dissociation free energy (∼70 kJ/mol for SH2-ST2/3 and ∼36 kJ/mol for SH2-ST2).

DISCUSSION

The recent crystal structure determination of amyloidogenic peptide GNNQQNY has provided a great deal of insights into the main features of fibril aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases (15). The ensuing application of different computational approaches has extended our knowledge of amyloid fibrils (17–19,21,35–38) and oligomeric forms (34,39–43). Furthermore, very recent structural analyses conducted on a variety of amyloidogenic sequences have provided additional support to the basic features of amyloid fibers inferred from the GNNQQNY structure (44). There are, however, some aspects, related essentially to the fiber formation process and to the structure of soluble oligomers, that remain largely unclear.

The results obtained from REMD investigations indicate clearly that GNNQQNY aggregates of moderate dimensions (3–5 strands per sheet), assembled in cross-β-spine steric zipper fashion, are rather stable. The smallest stable aggregate in 80ns REMD sampling is made of five (3 + 2) strands (Fig. 3 C). The removal of a single strand changes the scenario completely (Fig. 3A). Indeed, SH2-ST2 quickly undergoes large structural transitions. In this specific assembly, intersheet side chain/side chain interactions are quickly destroyed in the early stages of the simulation. The analysis of SH2-ST2 conformational space indicates that this system evolves toward novel conformational states (Fig. 3, A and B) characterized either by the opening of the structure or by the sliding of one sheet over the other (Fig. 3 B). Evidently, the SH2-ST2 intersheet surface, although made of interdigitated side chains, is not large enough to prevent structural rearrangements. In the stable SH2-ST2/3 system the larger intersheet interface keeps this aggregate in a state that mimics the one adopted by the fibril. In contrast to SH2-ST2, whose strands, in the initial configuration, are all extensively solvent exposed, in SH2-ST2/3 a single strand is located in an environment that resembles that found in prefibrillar states. The free energy perturbation (Fig. S13, Data S1) evidences a remarkable difference in the dissociation energies of SH2ST2 (∼36 kJ/mol) and SH2ST2/3 (∼70 kJ/mol). This data points out a considerable gain in stability of SH2ST2/3 compared to SH2ST2 consisting with the predominant population of the steric zipper basin in the REMD sampling (Fig. 3, D and E). Overall, these data indicate that the addition of a single strand in the steric zipper motif transforms a highly unstable SH2ST2 structure in an assembly (SH2ST2/3) with a significantly longer life-time thereby suggesting that the minimal stable nucleus for the aggregation process is composed by a very limited number of strands. Although the fiber formation process likely involves species not considered in this analysis, the instability of aggregates such as SH2-ST2 is in line with the presence of a lag phase in the fiber growth (16). Moreover, the remarkable increase in stability on the addition of a single strand may explain the quick change of the scenario shown by the fiber growth process. Remarkably, these findings also agree with the estimate, made by Eisenberg and co-workers (15), on the number of strands that compose the critical nucleus of GNNQQNY aggregates. Based on recent computer simulations, a limited number of peptide chains has also been proposed for the nucleus size of amyloidogenic peptides of different sequences, i.e., KFFE (45) and Aβ (16–22) (41).

Although the structural relationships between oligomeric and fibrillar species are yet to be fully defined, recent solid-state NMR and electron microscopy studies on a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of the β-amyloid peptide involved in Alzheimer's disease indicate that the intermediates and the fibrils share a common parallel β-sheet structural motif (46). Along this line, the analysis of the data on different stabilities of SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3 arranged in a fibril-like steric zipper motif may also hold functional implications on the toxic action exerted by amyloid oligomers (2,47,48).

Both SH2-ST2 and SH2-ST2/3 starting models are characterized by the presence of a large number of exposed backbone hydrogen bonding donors and acceptors. This feature makes these structures potentially unstable because it is known that edge strands are particularly reactive (49–55). Accordingly, it is not surprising that SH2-ST2 models undergo major rearrangements during the REMD simulation. Notably, the analysis of the most populated basins indicates that the REMD structures display a reduced number of exposed H-bond donors/acceptors. The instability of the steric zipper SH2-ST2 model is related to reactivity of the strands located at its ends, as they are solvent exposed (ready to react), rigid (even terminal strands shows an ordered structure–low entropic cost on interaction/association), and clustered (two or more of these strands are contiguous in space). The reactivity of these edge strands is further increased by the strong polarization induced by cooperative effects in β-sheet formation recently highlighted by quantum mechanics calculations (56).

On the other hand, data on SH2-ST2/3 assembly clearly indicate that, in slightly larger systems, steric zipper interactions are strong enough to stabilize the double-sheeted arrangement with these exposed-rigid-polarized-clustered (ERPC) strands. However, although steric zipper motif is able to keep stable the aggregate (3 + 2), reactive edge strands are still there. As shown in Fig. S13, Data S1, more than 20 H-bonds donors and acceptors are present in an SH2-ST2/3 assembly. This observation deserves some considerations. The reactivity of the edge strands is a driving force in the fibrils formation processes by promoting the elongation into ordered fibrils. Alternatively, these groups may interfere with several cellular components thereby generating cytotoxic effects. In this framework, fiber formation propensity and toxicity of oligomeric states might be connected to the same property: the hyper-reactivity of the ERPC strands.

The coexistence of two peculiar motifs (steric zipper and ERPC strands), rarely observed in PDB structures, makes GNNQQNY oligomeric aggregates very stable and, at the same time, reactive species. Because these effects depend basically on the status of backbone atoms, they are compatible with a variety of peptide sequences. The only requirement for side chains is the ability to form very strong interfaces, which maintain the strands in a reactive state within small-sized soluble, and likely diffusible, aggregates. Although hitherto only few detailed examples have been reported (15,44), it is presumable that stable interfaces may be achieved with a variety of structural mechanisms. It is likely that all factors that contribute to the stability of globular proteins, i.e., H-bonds, hydrophobic interactions, ion pair, etc., may be involved in these processes. For instance, in the case of the structural model for Alzheimer's β-amyloid fibrils (7) MD calculations (57) have shown that a limited number of peptide chains with a tight hydrophobic packing can form stable assemblies exhibiting similar properties of our SH2-ST2/3. Of course, ERPC strands are not necessarily associated with the steric zipper assembly (i.e., may also result from tertiary interactions in folded or partially folded structures).

All these considerations are in line with a multitude of evidences suggesting that different neurodegenerative diseases share a common molecular mechanism, although the proteins and the peptides directly involved present clearly unrelated sequences and functions (47,58,59). In this context, it is not surprising that fibril formation may have a protective role (60) and that inert fibrils may be reverted to neurotoxic protofibrils (61).

In this framework, a possible explanation to the puzzling properties of antibodies directed against amyloid oligomers can be proposed. Several investigations have shown that antibodies interact specifically with oligomeric species avoiding both monomeric and fibrillar forms (59,62). Moreover, a single antibody can recognize oligomeric species from different peptide/protein fragments (59,62–64). It may be surmised that the oligomeric states identified in this analysis, characterized by an exposed surface, presents terminal strands that differentiate them from both monomeric and fibril forms. Taking into account that the backbone is the most reactive part of this surface, it is likely that it represents the recognition patch of the antibodies that are able to target peptides with diversified sequences.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the strong interactions detected in the quasi-infinite assembly of crystalline GNNQQNY peptide (15) may be relevant to the formation and toxicity of soluble amyloid oligomers. Our analysis also highlights the role that MD and REMD can play in the characterization of other amyloid-like oligomers, starting from available experimental (44) and theoretical (65) steric zipper models.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Centro Regionale di Competenza in Diagnostica e Farmaceutica Molecolari for providing some of the facilities used to carry out this work. CINECA Supercomputing (project cne0fm4f and cne0fm2b) is acknowledged for computational support. The authors also thank Luca De Luca for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Ministero dell'lstruzione, Università e Ricerca (FIRB-contract No. RBNE03PX83). A.D.S is supported by European Molecular Biology Organization (fellowship No. 584-2007).

Alfonso De Simone's present address is Dept. of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road CB2 1EW, Cambridge, UK.

Editor: Edward H. Egelman.

References

- 1.Ross, C. A., and M. A. Poirier. 2004. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 10(Suppl):S10–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiti, F., and C. M. Dobson. 2006. Protein misfolding, functional amyloid, and human disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75:333–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kodali, R., and R. Wetzel. 2007. Polymorphism in the intermediates and products of amyloid assembly. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17:48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenberg, D., R. Nelson, M. R. Sawaya, M. Balbirnie, S. Sambashivan, M. I. Ivanova, A. O. Madsen, and C. Riekel. 2006. The structural biology of protein aggregation diseases: Fundamental questions and some answers. Acc. Chem. Res. 39:568–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh, D. M., and D. J. Selkoe. 2007. A beta oligomers—a decade of discovery. J. Neurochem. 101:1172–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritter, C., M. L. Maddelein, A. B. Siemer, T. Luhrs, M. Ernst, B. H. Meier, S. J. Saupe, and R. Riek. 2005. Correlation of structural elements and infectivity of the HET-s prion. Nature. 435:844–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petkova, A. T., Y. Ishii, J. J. Balbach, O. N. Antzutkin, R. D. Leapman, F. Delaglio, and R. Tycko. 2002. A structural model for Alzheimer's beta -amyloid fibrils based on experimental constraints from solid state NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:16742–16747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makin, O. S., E. Atkins, P. Sikorski, J. Johansson, and L. C. Serpell. 2005. Molecular basis for amyloid fibril formation and stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sikorski, P., and E. Atkins. 2005. New model for crystalline polyglutamine assemblies and their connection with amyloid fibrils. Biomacromolecules. 6:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan, R., and S. L. Lindquist. 2005. Structural insights into a yeast prion illuminate nucleation and strain diversity. Nature. 435:765–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaroniec, C. P., C. E. MacPhee, V. S. Bajaj, M. T. McMahon, C. M. Dobson, and R. G. Griffin. 2004. High-resolution molecular structure of a peptide in an amyloid fibril determined by magic angle spinning NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:711–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torok, M., S. Milton, R. Kayed, P. Wu, T. McIntire, C. G. Glabe, and R. Langen. 2002. Structural and dynamic features of Alzheimer's Abeta peptide in amyloid fibrils studied by site-directed spin labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 277:40810–40815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams, A. D., E. Portelius, I. Kheterpal, J. T. Guo, K. D. Cook, Y. Xu, and R. Wetzel. 2004. Mapping abeta amyloid fibril secondary structure using scanning proline mutagenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 335:833–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson, N., J. Becker, H. Tidow, S. Tremmel, T. D. Sharpe, G. Krause, J. Flinders, M. Petrovich, J. Berriman, H. Oschkinat, and A. R. Fersht. 2006. General structural motifs of amyloid protofilaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:16248–16253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson, R., M. R. Sawaya, M. Balbirnie, A. O. Madsen, C. Riekel, R. Grothe, and D. Eisenberg. 2005. Structure of the cross-beta spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature. 435:773–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balbirnie, M., R. Grothe, and D. Eisenberg. 2001. An amyloid-forming peptide from the yeast prion Sup35 reveals a dehydrated beta-sheet structure for amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:2375–2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng, J., B. Ma, C. J. Tsai, and R. Nussinov. 2006. Structural stability and dynamics of an amyloid-forming peptide GNNQQNY from the yeast prion sup-35. Biophys. J. 91:824–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez, A. 2005. What factor drives the fibrillogenic association of beta-sheets? FEBS Lett. 579:6635–6640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esposito, L., C. Pedone, and L. Vitagliano. 2006. Molecular dynamics analyses of cross-beta-spine steric zipper models: beta-sheet twisting and aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:11533–11538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Wel, P. C., J. R. Lewandowski, and R. G. Griffin. 2007. Solid-state NMR study of amyloid nanocrystals and fibrils formed by the peptide GNNQQNY from yeast prion protein Sup35p. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129:5117–5130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, C., Z. Wang, H. Lei, W. Zhang, and Y. Duan. 2007. Dual binding modes of Congo red to amyloid protofibril surface observed in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129:1225–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toyama, B. H., M. J. Kelly, J. D. Gross, and J. S. Weissman. 2007. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature. 449:233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugita, Y., and Y. Okamoto. 1999. Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berman, H., K. Henrick, H. Nakamura, and J. L. Markley. 2007. The worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): ensuring a single, uniform archive of PDB data. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D301–D303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berendsen, H. J. C., J. R. Grigerra, and T. P. Straatsma. 1987. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91:6269–6271. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Der Spoel, D., E. Lindahl, B. Hess, G. Groenhof, A. E. Mark, and H. J. Berendsen. 2005. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26:1701–1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Simone, A., A. Zagari, and P. Derreumaux. 2007. Structural and hydration properties of the partially unfolded states of the prion protein. Biophys. J. 93:1284–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Darden, T., D. York, and L. Pedersen. 1993. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seibert, M. M., A. Patriksson, B. Hess, and D. van der Spoel. 2005. Reproducible polypeptide folding and structure prediction using molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Biol. 354:173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gallicchio, E., M. Andrec, A. K. Felts, and R. M. Levy. 2005. Temperature weighted histogram analysis method, replica exchange, and transition paths. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:6722–6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia, A. E., and J. N. Onuchic. 2003. Folding a protein in a computer: an atomic description of the folding/unfolding of protein A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13898–13903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumketner, A., and J. E. Shea. 2007. The structure of the Alzheimer amyloid beta 10–35 peptide probed through replica-exchange molecular dynamics simulations in explicit solvent. J. Mol. Biol. 366:275–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng, J., B. Ma, and R. Nussinov. 2006. Consensus features in amyloid fibrils: sheet-sheet recognition via a (polar or nonpolar) zipper structure. Phys. Biol. 3:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strodel, B., C. S. Whittleston, and D. J. Wales. 2007. Thermodynamics and kinetics of aggregation for the GNNQQNY peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129:16005–16014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esposito, L., A. Paladino, C. Pedone, and L. Vitagliano. 2008. Insights into structure, stability, and toxicity of monomeric and aggregated polyglutamine models from molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 94:4031–4040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colombo, G., M. Meli, and A. De Simone. 2008. Computational studies of the structure, dynamics and native content of amyloid-like fibrils of ribonuclease A. Proteins. 70:863–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Simone, A., C. Pedone, and L. Vitagliano. 2008. Structure, dynamics, and stability of assemblies of the human prion fragment SNQNNF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 366:800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng, J., H. Jang, B. Ma, C. J. Tsai, and R. Nussinov. 2007. Modeling the Alzheimer Abeta17–42 fibril architecture: tight intermolecular sheet-sheet association and intramolecular hydrated cavities. Biophys. J. 93:3046–3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheon, M., I. Chang, S. Mohanty, L. M. Luheshi, C. M. Dobson, M. Vendruscolo, and G. Favrin. 2007. Structural reorganisation and potential toxicity of oligomeric species formed during the assembly of amyloid fibrils. PLoS Comput. Biol. 3:1727–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khandogin, J., and C. L. Brooks 3rd. 2007. Linking folding with aggregation in Alzheimer's β-amyloid peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:16880–16885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen, P. H., M. S. Li, G. Stock, J. E. Straub, and D. Thirumalai. 2007. Monomer adds to preformed structured oligomers of Abeta-peptides by a two-stage dock-lock mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:111–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gnanakaran, S., R. Nussinov, and A. E. Garcia. 2006. Atomic-level description of amyloid beta-dimer formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:2158–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soto, P., M. A. Griffin, and J. E. Shea. 2007. New insights into the mechanism of Alzheimer amyloid-beta fibrillogenesis inhibition by N-methylated peptides. Biophys. J. 93:3015–3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sawaya, M. R., S. Sambashivan, R. Nelson, M. I. Ivanova, S. A. Sievers, M. I. Apostol, M. J. Thompson, M. Balbirnie, J. J. Wiltzius, H. McFarlane, A. O. Madsen, C. Reikel, and D. Eisenberg. 2007. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 447:453–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melquiond, A., N. Mousseau, and P. Derreumaux. 2006. Structures of soluble amyloid oligomers from computer simulations. Proteins. 65:180–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chimon, S., M. A. Shaibat, C. R. Jones, D. C. Calero, B. Aizezi, and Y. Ishii. 2007. Evidence of fibril-like beta-sheet structures in a neurotoxic amyloid intermediate of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:1157–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bucciantini, M., E. Giannoni, F. Chiti, F. Baroni, L. Formigli, J. Zurdo, N. Taddei, G. Ramponi, C. M. Dobson, and M. Stefani. 2002. Inherent toxicity of aggregates implies a common mechanism for protein misfolding diseases. Nature. 416:507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haass, C., and D. J. Selkoe. 2007. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richardson, J. S., and D. C. Richardson. 2002. Natural beta-sheet proteins use negative design to avoid edge-to-edge aggregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:2754–2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laidman, J., G. J. Forse, and T. O. Yeates. 2006. Conformational change and assembly through edge beta strands in transthyretin and other amyloid proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 39:576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez, A., and H. A. Scheraga. 2003. Insufficiently dehydrated hydrogen bonds as determinants of protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:113–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Remaut, H., and G. Waksman. 2006. Protein-protein interaction through beta-strand addition. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31:436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dobson, C. M. 1999. Protein misfolding, evolution and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thirumalai, D., D. K. Klimov, and R. I. Dima. 2003. Emerging ideas on the molecular basis of protein and peptide aggregation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 13:146–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vitagliano, L., A. Ruggiero, C. Pedone, and R. Berisio. 2007. A molecular dynamics study of pilus subunits: insights into pilus biogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 367:935–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsemekhman, K., L. Goldschmidt, D. Eisenberg, and D. Baker. 2007. Cooperative hydrogen bonding in amyloid formation. Protein Sci. 16:761–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buchete, N. V., R. Tycko, and G. Hummer. 2005. Molecular dynamics simulations of Alzheimer's beta-amyloid protofilaments. J. Mol. Biol. 353:804–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobson, C. M. 2003. Protein folding and misfolding. Nature. 426:884–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Glabe, C. G. 2004. Conformation-dependent antibodies target diseases of protein misfolding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caughey, B., and P. T. Lansbury. 2003. Protofibrils, pores, fibrils, and neurodegeneration: separating the responsible protein aggregates from the innocent bystanders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26:267–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Martins, I. C., I. Kuperstein, H. Wilkinson, E. Maes, M. Vanbrabant, W. Jonckheere, P. Van Gelder, D. Hartmann, R. D'Hooge, B. De Strooper, J. Schymkowitz, and F. Rousseau. 2007. Lipids revert inert Abeta amyloid fibrils to neurotoxic protofibrils that affect learning in mice. EMBO J. 27:224–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kayed, R., E. Head, J. L. Thompson, T. M. McIntire, S. C. Milton, C. W. Cotman, and C. G. Glabe. 2003. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 300:486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Nuallain, B., and R. Wetzel. 2002. Conformational Abs recognizing a generic amyloid fibril epitope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:1485–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moretto, N., A. Bolchi, C. Rivetti, B. P. Imbimbo, G. Villetti, V. Pietrini, L. Polonelli, S. Del Signore, K. M. Smith, R. J. Ferrante, and S. Ottnello. 2007. Conformation-sensitive antibodies against Alzheimer amyloid-beta by immunization with a thioredoxin-constrained B-cell epitope peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 282:11436–11445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thompson, M. J., S. A. Sievers, J. Karanicolas, M. I. Ivanova, D. Baker, and D. Eisenberg. 2006. The 3D profile method for identifying fibril-forming segments of proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:4074–4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.