Abstract

The non-natural photoreactive amino acid p-Benzoyl-L-Phenylalanine (Bpa) was incorporated into the RNA polymerase (Pol) II surface surrounding the central cleft formed by the Rpb1 and Rpb2 subunits. Photocrosslinking of Preinitiation Complexes (PICs) with these Pol II derivatives and hydroxyl radical cleavage assays revealed that the TFIIF dimerization domain interacts with the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains adjacent to Rpb9 while TFIIE crosslinks to the Rpb1 clamp domain on the opposite side of the Pol II central cleft. Mutations in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains were found to alter both Pol II-TFIIF binding and the transcription start site, a phenotype associated with mutations in TFIIF, Rpb9, and TFIIB. In combination with previous biochemical and structural studies, these new findings illuminate the structural organization of the PIC and reveal a network of protein-protein interactions involved in transcription start site selection.

The earliest step in transcription initiation is recruitment of Pol II and the general transcription factors to form the Preinitiation Complex (PIC)1. Upon addition of ATP, the PIC transitions to the Open Complex state, resulting in separation of the DNA strands surrounding the transcription start site and insertion of the template strand into the active center of Pol II. Next, Pol II must locate the transcription start site, which in S. cerevisiae, can be over 60 base pairs distant from the initial site of DNA strand separation2. Mutations in the general factor TFIIF and in the B-finger domain of the general factor TFIIB can alter the transcription start site, suggesting these two factors are involved in start site recognition3-7. Consistent with this role, crystallography and protein-protein crosslinking in the PIC have positioned both of these factors within the Pol II active site cleft8-10. Additionally, mutations in the Pol II subunit Rpb9 have been found to alter the transcription start site, but it remains unclear how this subunit, which is located distant from the Pol II active site, participates in start site selection11,12.

Initiation of RNA synthesis begins with DNA-NTP base pairing, phosphodiester bond formation, and translocation of the DNA-RNA hybrid within the active center of Pol II. After synthesis of 8−12 bases of RNA, Pol II escapes from the promoter into a stable elongation state13-15. The nucleation of transcription factors at the promoter and the structural transition into the open and elongation complexes involves a complex set of protein-protein and protein-DNA interactions. Elucidating these molecular interactions within the transcription machinery is important for understanding the functional roles of the general transcription factors and the mechanisms of transcription regulation.

At the center of the transcription machinery, the 12-subunit Pol II enzyme contains two large subunits, Rpb1 and Rpb2, that form a central cleft for nucleic acid entry and contain the enzyme active site16-18. The remaining 10 smaller subunits (Rpb3-Rpb12) surround these two largest subunits to provide structural support and to regulate Pol II enzymatic activity. Photocrosslinking and hydroxyl radical-generating probes positioned on yeast TFIIB in combination with structural studies have suggested a model for PIC architecture where TFIIB, in combination with TFIIF, is positioned over the Pol II central cleft and wall domain8,9 (termed “flap” in bacterial Pol). TFIIB binding to this location in association with the TBP-DNA complex has been proposed to bend promoter DNA around Pol II and to position the promoter above the central cleft. In agreement with this model, hydroxyl radical-generating probes linked to promoter DNA suggest that the path of DNA lies above the central cleft19. Additionally, this study, along with earlier protein-DNA crosslinking studies in the human transcription system20-23, suggested that TFIIF, TFIIE, and TFIIH are positioned near the central cleft. Cryo EM studies of the Pol II-TFIIF complex have suggested that TFIIF lies adjacent to the central cleft and the Rpb1 clamp domain24 (termed “β’ pincer” in bacterial Pol).

A limitation of our previous photocrosslinking studies designed to probe the architecture of the PIC was that the photoprobe used was specific for incorporation at surface exposed cysteine residues, requiring protein engineering to generate polypeptides with single surface cysteines. This approach is impractical for large multisubunit proteins and/or proteins with essential cysteine residues. To overcome this limitation in the present work, we used a system to incorporate photoreactive non-natural amino acids in S. cerevisiae. Using this system, we were able to position short crosslinking probes on the Pol II surface surrounding the central cleft and to map the interactions of Pol II in the PIC with TFIIB, TFIIF, and TFIIE. Our results reveal a surprising location for Pol II-TFIIF binding that can explain the role of Rpb9 in transcription start site selection. This TFIIF location was confirmed by Pol II mutagenesis and biochemical analysis. Together, our results reveal a protein-protein interaction network within the PIC that is involved in the mechanism of transcription initiation and start site selection.

RESULTS

Insertion of a non-natural amino acid photocrosslinker

To insert the photoreactive amino acid Bpa into components of the transcription machinery, we modified the system developed by Chin et al25, which consists of a yeast replicating plasmid expressing an E. coli tRNATyr amber suppressor tRNA and the E. coli Tyr tRNA synthetase selected to charge the suppressor tRNA with Bpa26 (Fig 1a,b). In preliminary tests, we found that expression of the tRNA from this plasmid was poor since it lacked a yeast Pol III promoter, and this limited the suppression efficiency of the system. To improve efficiency, we tested strong, medium, and weak yeast Pol III promoters driving expression of the suppressor tRNA27. While a strong promoter resulted in very slow growth of yeast, presumably due to high levels of amber codon suppression, the medium strength N(GTT)PR promoter allowed expression of near normal levels of several protein-Bpa derivatives using the conditions described below.

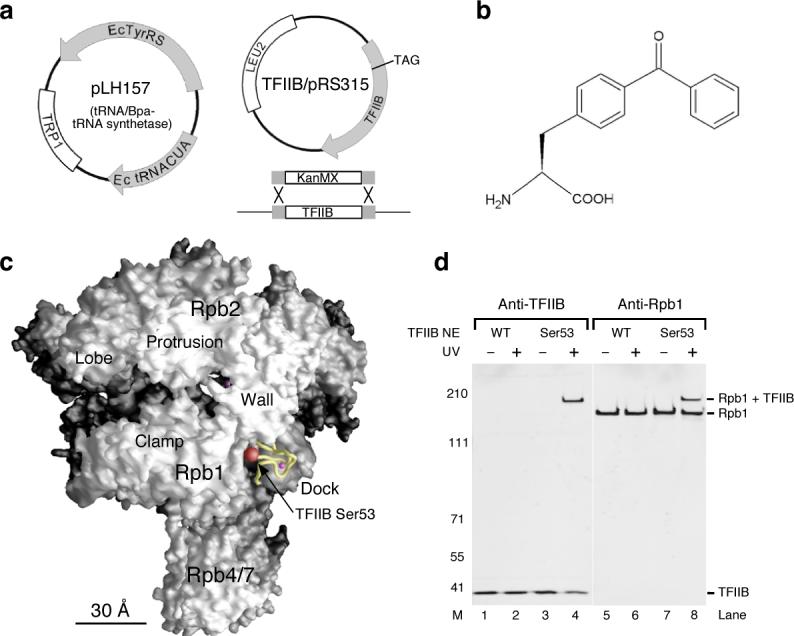

Figure 1. Incorporation of the non-natural amino acid p-Benzoyl-L-Phenylalanine (Bpa) to TFIIB and photocrosslinking.

(a) Two plasmids in the TFIIB amber strain. Plasmid pLH157 (Trp1+) contains orthogonal tRNA synthetase (Ec TyrRS) and tRNA (Ec tRNACUA) genes for incorporating Bpa through nonsense suppression of the TAG codon. Plasmid TFIIB/pRS315 (Leu2+) is transformed through plasmid shuffling into the yeast strain containing replacement of chromosomal TFIIB by the KanMX marker. (b) The chemical structure of the photocrosslinker Bpa26. (c) Position of the TFIIB ribbon domain on the Pol II surface. The TFIIB ribbon (yellow backbone with a magenta sphere representing the zinc atom) is modeled onto the surface of a 12-subunit Pol II structure based on superposition of the Pol II-IIB co-crystal structure (PDB code: 1R5U10) with two other Pol II structures: a 12-subunit Pol II (PDB code: 1WCM18) and a Pol II elongation complex (PDB code: 1SFO42). This model of the Pol II surface is used throughout the figures. Location of Ser53 on the ribbon domain is shown with the red sphere representing the entire serine residue including backbone and side-chain atoms. All structural figures were generated using Grasp43. (d) Western analysis of TFIIB-Bpa crosslinking within the PIC. As indicated, TFIIB Ser53-Bpa is crosslinked to Rpb1. The fusion protein band (Rpb1+TFIIB) is recognized by the two antibodies (see METHODS). TFIIB NE: TFIIB-Bpa nuclear extract. UV: UV irradiation. M: molecular weight marker.

To validate this approach in probing protein-protein interactions within the PIC, we first inserted Bpa at a position in the TFIIB zinc ribbon domain (Ser53) that was known to crosslink to the Rpb1 clamp domain from our previous study8 and is positioned near Rpb1 in the TFIIB-Pol II crystal structure10 (Fig. 1c). We constructed a yeast strain containing a deletion of the chromosomal copy of TFIIB, a plasmid encoding TFIIB with a TAG codon at position 53, and the plasmid pLH157 encoding the modified suppressor tRNATyr/Bpa synthetase plasmid (Fig. 1a). Since TFIIB is an essential protein, the strain grew only when Bpa was supplied in the media. Nuclear extracts were prepared both from this strain and from a control strain containing no amber mutation in the TFIIB plasmid (Wild Type). PICs were formed and isolated by incubating the nuclear extract with promoter templates immobilized to magnetic beads. These PICs were irradiated with UV light and the products analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. As demonstrated in Figure 1d, a slowly migrating band is observed only when PICs formed using TFIIB Ser53-Bpa were treated with UV light. This slowly migrating polypeptide contains both Rpb1 and TFIIB, as demonstrated by Western blot (compare Fig. 1d, lanes 4 and 8) and is therefore a crosslinking product between TFIIB and Rpb1. This experiment validates the use of this system for site-specific photoreactive probe insertion within the PIC. Unlike the cysteine-specific incorporation of biochemical probes used in our previous experiments for small proteins such as TFIIB, TFIIA, and activation domains8,28-30, this method is applicable to large polypeptides containing multiple cysteines and to subunits of large protein complexes (see below) as long as protein function is not compromised by Bpa insertion.

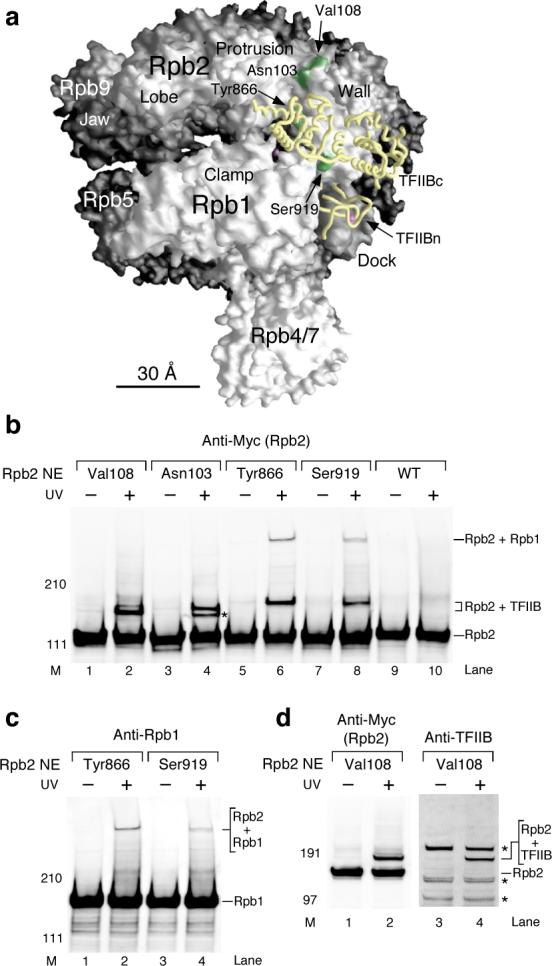

The Rpb2 wall crosslinks to the TFIIB core domain

Previous site-specific biochemical probing using cysteine-specific photocrosslinking and hydroxyl radical cleavage reagents allowed us to map the TFIIB core domain positioned over the central cleft and wall domain of Rpb29(Fig. 2a). To further investigate proteins targeting the wall domain and to confirm our previous model, we used the non-natural Bpa incorporation system to insert Bpa at 4 locations on the wall surface (Fig. 2a). For these experiments, a yeast strain was constructed analogous to that described in Figure 1a except that the chromosomal copy of RPB2 was disrupted and the amber plasmid contained the Rpb2 coding sequence with a TAG mutation at the indicated positions. These strains also required Bpa in the media for growth. Nuclear extracts prepared from these strains were used for PIC formation, irradiated with UV light, and analyzed by Western blot. As shown in Figure 2b, Bpa incorporated at positions Tyr866 and Ser919 crosslinked with Rpb1 (Fig. 2b, lanes 6 and 8), consistent with the locations of these two amino acids near Rpb1 in the Pol II structure (Fig. 2a). The identity of this Rpb1-Rpb2 crosslinked product was shown by probing a duplicate Western blot with Rpb1 antibody where an identical mobility shift in Rpb1 was observed (Fig. 2c, lanes 2 and 4). We also found that Bpa at Rpb2 positions Val108, Asn103, Tyr866, and Ser919 all crosslinked to TFIIB (Fig. 2b, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). The identity of the crosslinked product was confirmed as above by showing this crosslinked product reacted with antisera directed against both Rpb2 and TFIIB (Fig. 2d, lanes 2 and 4 and data not shown).

Figure 2. Photocrosslinking confirms the binding between the TFIIB core domain and the Rpb2 wall domain within the PIC.

(a) Molecular surface of Pol II and model of TFIIB position within the PIC. The TFIIB core domain (TFIIBc, yellow backbone) is modeled on the Pol II surface based on previous site-specific biochemical analyses using IIB cysteine mutants9. The TFIIB ribbon is modeled as in Fig 1c. The locations of Bpa on the Rpb2 wall are shown with the green colored patches on the surface. The magenta sphere within the central cleft of Pol II denotes the Mg atom inside the active site. (b) Western analysis of Rpb2 photocrosslinking. Rpb2 and crosslinking bands were revealed with anti-Myc antibody against the Myc epitope-tagged Rpb2. As indicated, the crosslinked proteins were identified as TFIIB and Rpb1 (see below, (c) and (d)). Rpb2 NE: Rpb2-Bpa nuclear extract. UV: UV irradiation. M: molecular weight marker. Asterisk: unidentified crosslinking target. (c) Identification of the crosslinked protein Rpb1. Anti-Rpb1 antibody against the first 200 amino acids of Rpb1 was used to validate the crosslinking target for Tyr866- and Ser919-Bpa. (d) Representative validation of Rpb2-TFIIB crosslinking. The antibody against TFIIB was used to reveal TFIIB in the crosslinking band (Rpb2+TFIIB) from Rpb2 Val108-Bpa. Asterisk: non-TFIIB background.

While the positions of Rpb2 Asn103, Ser919 and Tyr866 on Rpb2 are all adjacent to the TFIIB core domain in our previous PIC models, the location of Rpb2 Val108 is approximately 10 Å distant from the permissible crosslinking range for Bpa. Further movement of the core domain to a position closer to Val108 is prevented in the current model, which uses the structure of the elongating form of RNA Pol II. In our model, the TFIIB core domain was positioned by docking the structure of TFIIB core/TBP/TATA box ternary complex31,32 onto the surface of elongating Pol II and extending the downstream DNA with straight B-form DNA. Repositioning of the TFIIB core to permit Val108 crosslinking would generate a potential clash between the downstream DNA and the Rpb2 protrusion domain (termed “β pincer” in bacterial Pol). We suspect that a slight conformational change in either the Rpb2 wall or protrusion domains and/or a DNA path different from straight B-form DNA will be needed to permit a slight adjustment of TFIIB core position with respect to Val108. Nonetheless, our crosslinking shows that the TFIIB core domain interacts with the wall domain of Rpb2, and, given the condition of minor adjustments directed by future structural analysis, our model of the PIC provides a close approximation of PIC architecture.

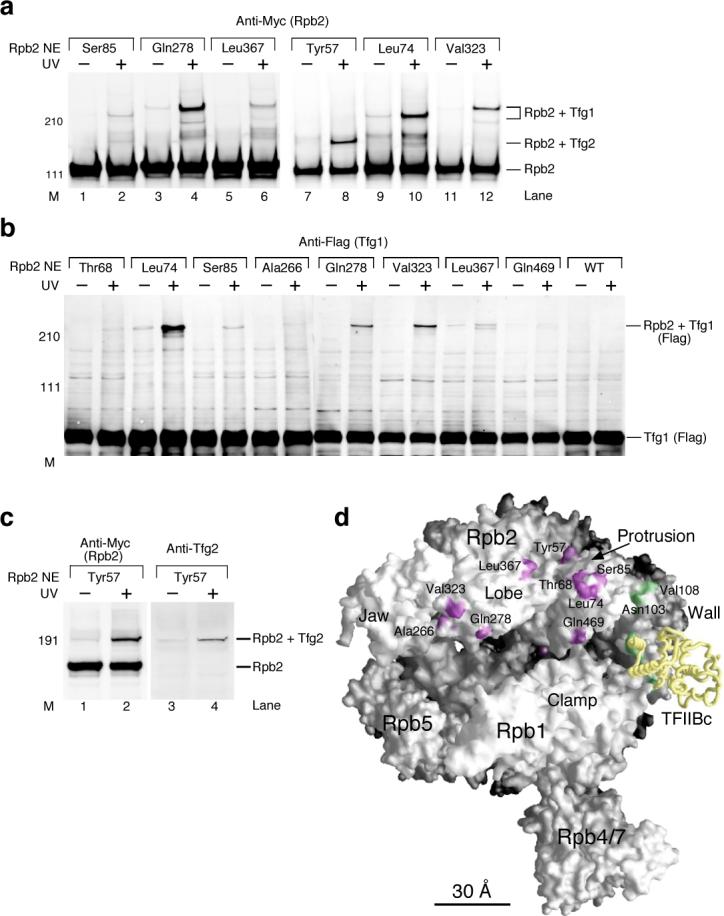

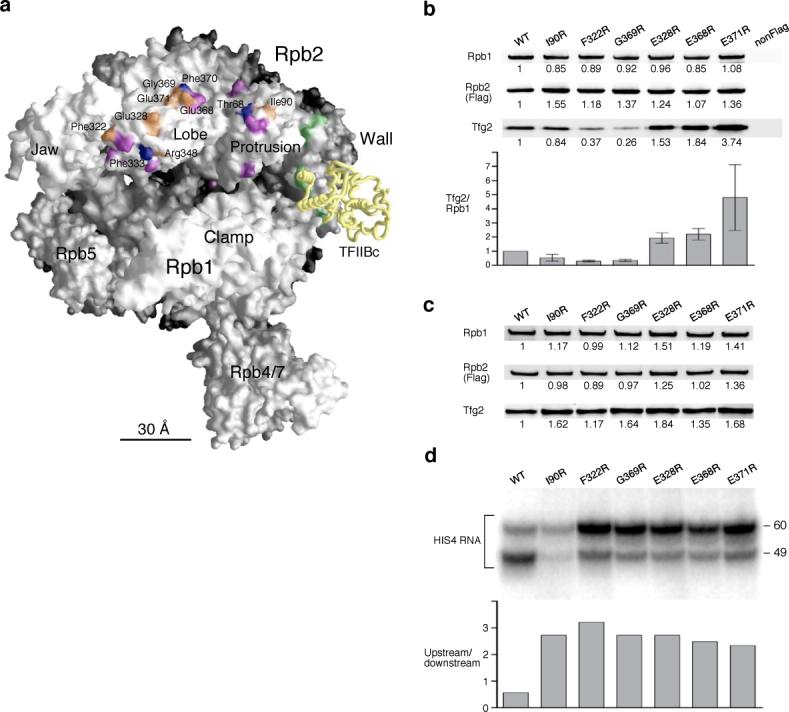

Mapping the binding sites for TFIIF and TFIIE on Pol II

As described above, previous studies have indicated that the face of Pol II containing the central cleft is likely to be in close contact with subunits of general factors including TFIIF and TFIIE. To map these interactions, Bpa was first incorporated into residues in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains (Fig. 3), and these derivatives were used for crosslinking in isolated PICs. As demonstrated in Figure 3a, Bpa incorporated in these domains of Rpb2 extensively crosslinks to other polypeptides in PICs. To identify these crosslinked polypeptides, the experiment was repeated with added recombinant TFIIF in which the large TFIIF subunit (Tfg1) was Flag epitope-tagged. Western analysis of these crosslinking reactions with Anti-Flag antisera showed that almost all these Rpb2 positions crosslinked to Tfg1 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, probing the crosslinking reactions with the TFIIF small subunit antibody (Anti-Tfg2) showed that Rpb2 Tyr57 crosslinks to Tfg2 (Fig. 3a, lane 8; Fig. 3c, lanes 2 and 4). Mapping these Tfg1 and Tfg2 crosslinking sites onto the Pol II surface indicates that TFIIF extensively contacts the upper side of the central cleft (Fig. 3d). Our photocrosslinking results thus reveal a very different view of TFIIF interaction on the Pol II surface compared with the cryo-EM study of Pol II-TFIIF in which Tfg2 was proposed to be present mainly in the Pol II central cleft, with much of Tfg1 density located near the Pol II clamp domain.

Figure 3. TFIIF binds the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains within the PIC.

(a) Western analysis of Rpb2 photocrosslinking. Anti-Myc antibody against the Myc epitope tagged Rpb2 was used to reveal Rpb2 and crosslinking products. As indicated, Tfg1 and Tfg2 subunits of TFIIF were identified as the crosslinked proteins (see below, (b) and (c)). Rpb2 NE: Rpb2-Bpa nuclear extract. M: molecular weight marker. UV: UV irradiation. (b) Tfg1 was identified as the crosslinked polypeptide with Rpb2-Bpa mutants. Identification was based the method using the recombinant TFIIF containing Flag epitope tagged Tfg1 (see METHODS). Flag tagged Tfg1 was revealed by Western analysis using the anti-Flag antibody. The crosslinking bands (Rpb2+Tfg1) were also shown to contain Myc epitope tagged Rpb2 by staining with the anti-Myc antibody (data not shown). (c) Tfg2 crosslinked to Bpa positioned at Tyr57 of Rpb2. Anti-Myc antibody was used to reveal Myc epitope tagged Rpb2 and crosslinking bands, and anti-Tfg2 antibody was used to validate the crosslinked Tfg2. (d) Locations of Rpb2-Bpa crosslinked to TFIIF. Purple patches on the Pol II surface indicate Rpb2-TFIIF crosslinking positions. Same as Figure 2a, Bpa positions crosslinked with TFIIB are colored green and the TFIIB core domain (TFIIBc) is shown as the yellow backbone. The magenta sphere within the central cleft of Pol II denotes the magnesium atom in the active site.

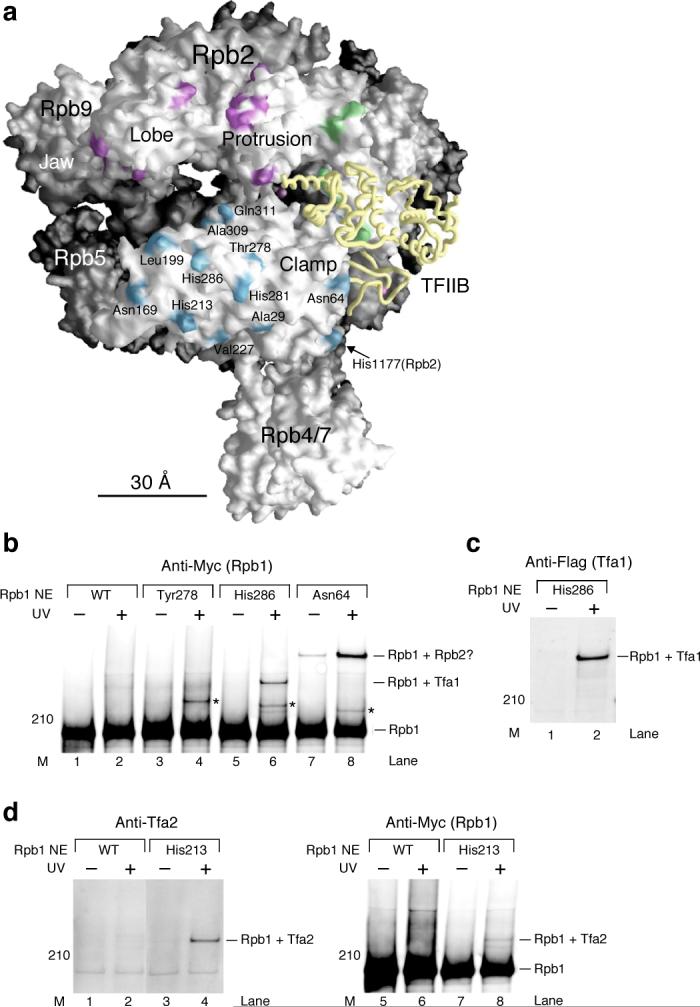

To test interactions with the clamp domain, the Bpa photocrosslinker was incorporated into Rpb1 on the opposite side of the central cleft from the Rpb2 lobe/protrusion domains (Fig. 4a). As shown in Figure 4b-d, Rpb1 His213 and His286 were found to crosslink to Tfa2 and Tfa1 respectively, subunits of the heterodimeric TFIIE. Western analysis confirmed these crosslinked polypeptides as Tfa1 and Tfa2 (Fig. 4c-d). Rpb1 His213 and His286 are both located at the edge of the clamp domain.

Figure 4. TFIIE interacts with the Rpb1 clamp domain within the PIC.

(a) Positions of Bpa in the Rpb1 clamp domain are displayed as the light blue patches on the Pol II surface. One Bpa position (His1177) belongs to the Rpb2 subunit. Positions of Rpb2-Bpa crosslinked to TFIIF (Fig. 3; Tfg1 and Tfg2) and TFIIB (Fig. 2) are colored purple and green, respectively. TFIIB backbone is colored yellow. The magenta sphere inside the central cleft denotes the active site Mg atom. (b) Western analysis of photocrosslinking using Rpb1-Bpa mutants. Rpb1 and crosslinking bands were revealed by the anti-Myc antibody against Myc epitope tagged Rpb1. As indicated, the crosslinked protein for His286-Bpa was identified as Tfa1 (see below, (c)). One of the crosslinked proteins for Asn64-Bpa is likely Rpb2 (Rpb1+Rpb2?) based on the structure of Pol II. Asterisk: crosslinked protein has not been identified. Rpb1 NE: Rpb1-Bpa nuclear extract. M: molecular weight marker. UV: UV irradiation. (c) The crosslinked protein for His286-Bpa is identified to be Tfa1. Identification of Rpb1-Tfa1 crosslinking is based on the mixing method described in METHODS. Anti-Flag antibody was used to reveal Tfa1. The same crosslinking band was also recognized by the anti-Myc antibody against Myc epitope tagged Rpb1 (data not shown). (d) The crosslinked protein for His213-Bpa is Tfa2. Anti-Tfa2 antibody and anti-Myc antibody (Rpb1) were used in the Western analysis to validate Rpb1-Tfa2 crosslinking.

Rpb1 Asn64 crosslinks to a large polypeptide which we presume to be Rpb2 given the proximity of Asn64 to Rpb2 in the Pol II structure (Fig. 4b, lane 8; Rpb1+Rpb2?). Although most positions of Bpa incorporation in the clamp domain showed no detectable crosslinking (data not shown), three positions (Thr278, His286, Asn64) each showed crosslinking to a polypeptide that we have not yet been able to identify (Fig. 4b, lanes 4, 6, and 8; labeled with *). Thus far, we have confirmed that this crosslinked polypeptide is neither Tfa1 or Tfg2. In the Pol II-TFIIF cryo EM structure24, one structural fragment of Tfg2 was proposed to contact the edge of the clamp domain, and a large fragment of Tfg1 occupies the space between the bottom of the clamp and Rpb4/7 dimer. However, none of our Bpa positions on the clamp crosslinked with these two TFIIF subunits. In particular, Bpa positions on the bottom of the clamp, including Rpb1 Ala29 and Val227 and Rpb2 His1177 (Fig. 4a), yielded no detectable crosslinking.

Mutations in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains

The finding that TFIIF extensively contacts the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains led us to test how this interaction contributes to transcription initiation. Previously, studies by Young, Hampsey, and coworkers have identified mutations in this Rpb2 area that affect the accuracy of transcription initiation5,33. We generated yeast strains containing radical mutations on the surface of the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains. As shown in Figure 5a, several mutations near the positions that crosslinked to IIF (purple) were found to be lethal (blue) or caused slightly slow growth at nonpermissive temperatures (orange). To test whether these mutations affect Pol II-TFIIF binding, a co-immune precipitation experiment was conducted using anti-Flag agarose beads to purify Flag epitope-tagged Pol II variants with Rpb2 mutations and test for co-precipitation of TFIIF. Results were quantitated by measuring the ratio of co-precipitated Rpb1 (Pol II) and Tfg2 (TFIIF). As shown in Figure 5b, three Rpb2 mutations significantly decrease binding between TFIIF and Pol II, with Rpb2 Phe322R and Gly369R each reducing Tfg2 co-precipitation 3−4 fold. Surprisingly, three Rpb2 mutations changing glutamic acid to arginine at positions 328, 368 and 371 all increased the association of Tfg2 with Pol II. Although it was unexpected to find mutations that increased the affinity of TFIIF for Pol II, the fact that six mutations on the lobe and protrusion domain surface all altered the interaction of Pol II with TFIIF supports the crosslinking studies indicating that TFIIF binds Pol II in this location.

Figure 5. Rpb2 lobe/protrusion mutations alter Pol II-IIF interaction and confer an upstream shift in the transcription start site.

(a) Model of the Pol II surface and mutations in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains. Mutations of Rpb2 that demonstrated slow growth phenotype are colored orange. Lethal mutations are colored blue. Purple and green patches denote Bpa positions that are crosslinked to TFIIF (Fig. 3) and TFIIB (Fig. 2), respectively. TFIIB backbone (TFIIBc; TFIIB core domain) is colored yellow. (b) Mutations in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains affect TFIIF binding. Co-immune precipitation was conducted with the anti-Flag agarose gel to pull down TFIIF and Pol II containing Flag epitope tagged Rpb2. Rpb2 mutations are indicated on top. Anti-Rpb1, anti-Flag (Rpb2) and anti-Tfg2 antibodies were used in the Western analysis. The relative intensity of immune staining was normalized against the wild-type (WT) and is listed below each protein band. NonFlag: Wild-type Rpb2 without Flag epitope tag. The intensity ratio between Tfg2 and Rpb1 is displayed in the bottom panel. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (n=3). (c) PIC formation is not affected by the Rpb2 mutations. The immobilized template assay (PIC formation) using the Rpb2 mutant nuclear extracts was analyzed by Western blotting. The relative intensity of each protein was normalized as described in (b). (d) Pol II transcription initiation is affected by the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion mutants. The transcription start sites for the Rpb2 mutants were analyzed by in vitro transcription and primer extension. All Rpb2 mutants shift the preference for transcription start to the upstream site (−60; relative to the ATG translation start codon of the HIS4 gene). The ratio of upstream and downstream start sites (−60/−49) is shown in the lower panel.

The ability of these Rpb2 derivatives to form stable PICs was further assessed by using nuclear extracts to form PICs on immobilized promoter templates (Fig. 5c). Extracts prepared from these mutants were all able to form PICs at normal levels, suggesting that interactions among the other PIC components compensate for mutations that reduce Pol II-TFIIF binding. Since DNA probes indicate that TFIIF lies near promoter DNA both upstream and downstream of the TATA19, it is also possible that in the PIC, Tfg1 and Tfg2 interact with other surfaces of Pol II in addition to the lobe and protrusion domains, reducing the effects of the Rpb2 mutations. The transcriptional phenotype of these Pol II mutants was also determined. Strikingly, all mutations generate an upstream shift in the transcription start site at the yeast HIS4 promoter (Fig. 5d). In wild type extracts, the downstream start site is preferred by approximately two-fold over the upstream start site. In contrast, all the mutants prefer the upstream start site by at least a five-fold change in this ratio. This result indicates that these mutations affect a step after PIC formation that involves selection of the transcription start site.

TFIIF dimerization domain contacts Rpb2 lobe/protrusion

The two largest subunits of yeast TFIIF, Tfg1 and Tfg2, are homologous to the Rap74 and Rap30 subunits of human TFIIF. The smallest yeast TFIIF subunit, Tfg3, is not conserved with metazoan TFIIF, is not essential for yeast growth, and is also a subunit of yeast TFIID and chromatin remodeling complexes such as Swi/Snf and Ino80. Rap74 and Rap30 form a beta-barrel dimerization fold with their respective N-terminal domains34. Based on sequence alignment, the N-terminal domains of Tfg1 and Tfg2 also contain conserved sequence blocks that are likely to form a hetero-dimeric structure similar to the Rap74/Rap30 beta-barrel (Supplementary Fig. 2). Hampsey, Ponticelli, and coworkers have described mutations in Tfg1 and Tfg2 that cause transcription start site shifts similar to those seen with the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion mutants6,7. These IIF mutations are located within the predicted dimerization regions of Tfg1 and Tfg2. Since the similarity between yeast and human Tfg1 is weak, we directly tested whether the region of Tfg1 encompassing these transcription start site changes was required for TFIIF dimerization. Co-translation of Tfg1 residues 1−424 and Tfg2 residues 1−230 allowed co-precipitation of Tfg1 with Tfg2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast, Tfg1 residues 1−375 or shorter derivatives did not co-precipitate with Tfg2, showing that the Tfg1 dimerization domain extends between residues 375−424 and supporting the alignment shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

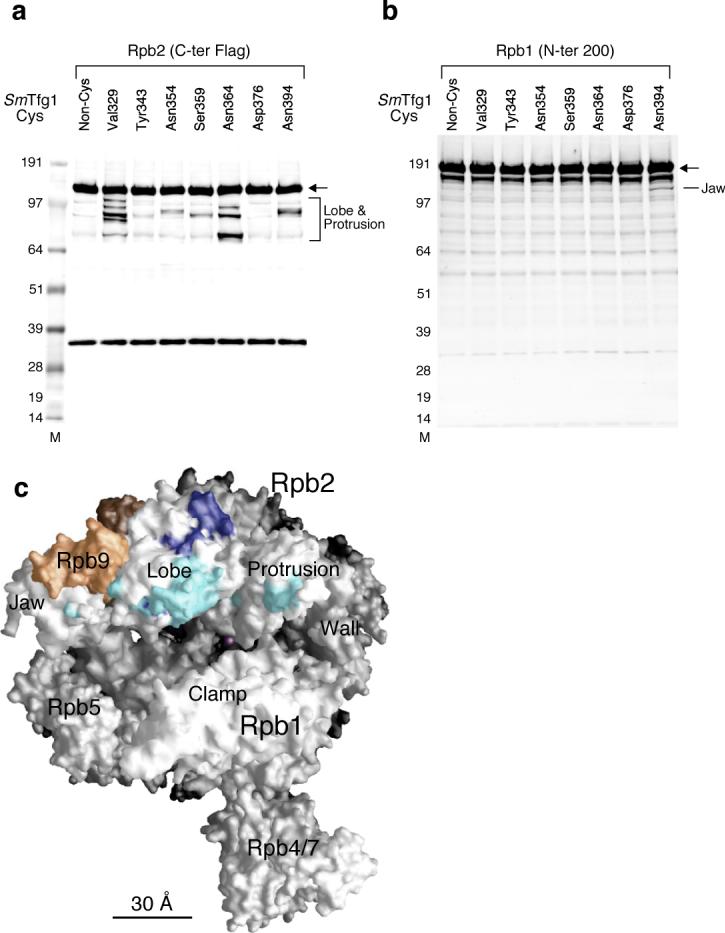

To test if this dimerization region was responsible for binding to the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains, we used a hydroxyl radical cleavage assay where FeEDTA probes were attached to Tfg1 at positions proximal to the Tfg1 mutations that were found to alter start site selection. To accomplish this, we generated recombinant TFIIF derivatives lacking all endogenous cysteine residues and with inserted cysteine residues at one of 7 positions (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 4a). FeBABE was attached to these seven TFIIF derivatives as described8, and all modified proteins were functional in a transcription assay (Supplementary Fig. 4). These proteins were added to nuclear extracts containing Flag epitope tagged Rpb2 or Rpb1, and PICs were formed and isolated on immobilized promoter templates. Hydroxyl radical cleavage was activated by addition of peroxide and a reducing agent, and the products of the reaction were analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 6a-b). The cleavage sites were determined based on a previously described method using in vitro translated Flag tagged Rpb2 and Rpb1 peptides as molecular weight standards8 (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), and the results were mapped on the Pol II structure where dark blue represents strong cleavage and light blue reflects weaker cleavage (Fig. 6c). We observed extensive cleavage on the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains closely approaching the position of Rpb9, as well as cleavage in the Rpb1 jaw region (Fig. 6c). These results, combined with the data presented above, indicate that the TFIIF dimerization domain interacts with the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains where it mediates transcription start site selection. Since TFIIF binds adjacent to Rpb9, we propose that mutations in Rpb9 that alter the transcription start site11,12 do so because of altered interactions with TFIIF.

Figure 6. Site-specific hydroxyl radical protein cleavage reveals the binding site for the TFIIF dimerization domain within the PIC.

(a) Cleavage fragments of Rpb2 with the Flag epitope attached at the C-terminus were visualized by Western analysis with anti-Flag antibody. Cysteine mutation sites in SmTfg1 recombinant TFIIF cys variants are indicated. A non-Cys SmTfg1 is included as a control. The specific cleavage fragments correspond to cut sites in the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains. The arrow points to full length Rpb2. M; molecular size marker. (b) Cleavage fragments of Rpb1 were visualized by Western analysis with antibody against the first 200 residues of Rpb1. SmTfg1 FeBABE derivatives are indicated. The specific cleavage fragment in N394C corresponds to cut sites in the Rpb1 jaw domain. The arrow points to full length Rpb1. (c) The calculated FeBABE cleavage sites (Supp Figs 4,5) for SmTfg1 dimerization domain Cys variants were mapped to the surface of the Pol II. A nine-residue segment centered at the calculated cleavage site is colored light blue (weak cleavage) or dark blue (strong/medium cleavage). The magenta sphere located deep inside the active site represents the active site Mg. Rpb9 is colored orange.

DISCUSSION

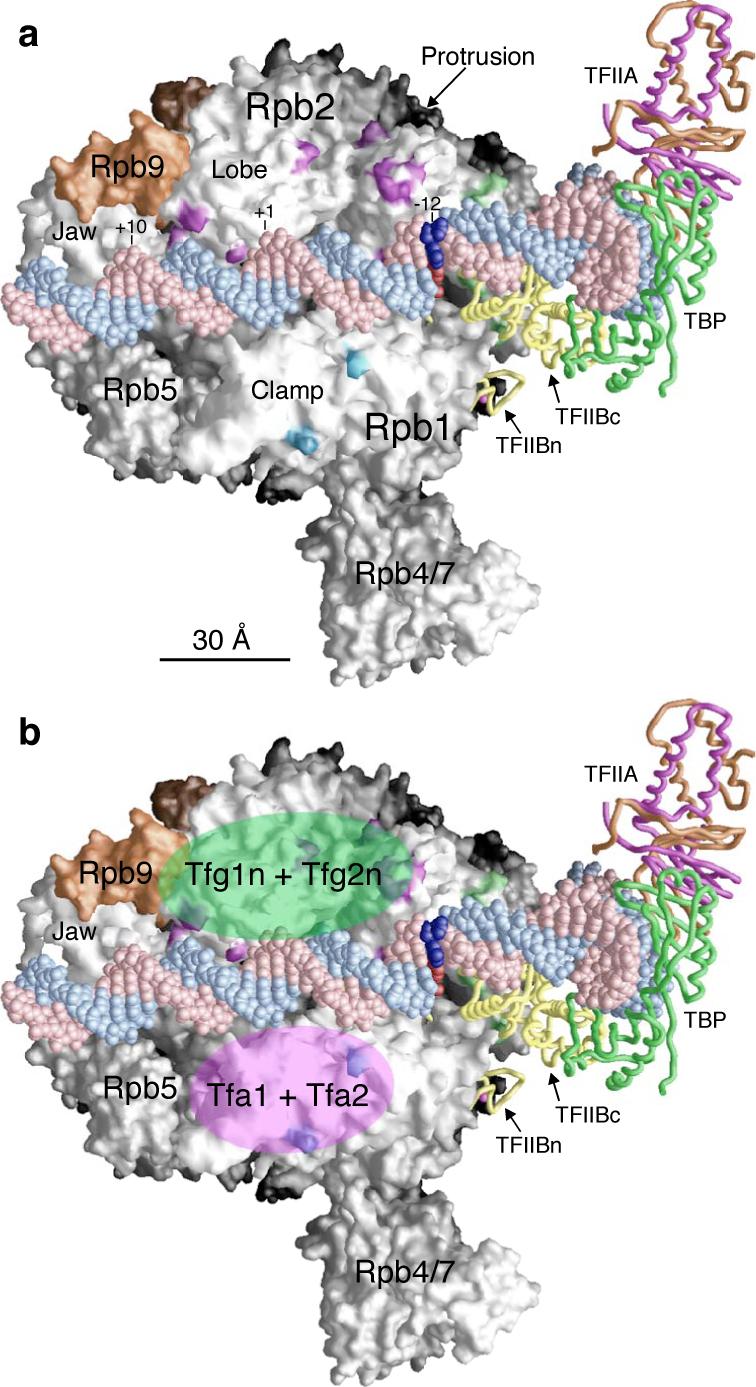

Using site-specific incorporation of a short photoreactive amino acid, we have mapped the binding locations of TFIIB, TFIIF, and TFIIE on the surface of RNA Pol II. The localization of TFIIF and TFIIE to opposite sides of the Pol II central cleft shows how these factors are in position to affect post-recruitment steps in the mechanism of transcription initiation. Previously, we proposed a model for the binding of TFIIA/TFIIB/TBP/DNA on Pol II based on photocrosslinkers attached to TFIIB, hydroxyl radical generating probes attached to TFIIB and promoter DNA, and structural studies of these factors8-10,19,31,32,35,36 (Fig. 7a). Our new findings demonstrate that in the PIC, the TFIIF dimerization domain interacts with the Rpb2 lobe and protrusion domains, while TFIIE makes close contacts with the Rpb1 clamp domain (Fig 7a,b). These results were surprising, as the previous cryo EM structure model for the Pol II-TFIIF complex proposed that TFIIF mainly binds to the central cleft and clamp regions of Pol II24. Our studies find no evidence for TFIIF directly interacting with the clamp domain, however, our localization of TFIIF and TFIIE are consistent with the positioning of these factors based on protein-DNA crosslinking and hydroxyl radical cleavage assays19,20,23. As described below, this positioning of TFIIF can explain how mutations very distant from the Pol II active site can affect transcriptional start site selection.

Figure 7. Model of PIC assembly.

(a) Model of the complex is based on TFIIB core domain (TFIIBc) binding to Pol II from previous biochemical analyses and non-natural amino acid photocrosslinking in this study. TFIIA, TBP, and DNA were fitted into the complex based on the crystal structures of human TFIIB core/TBP/TATA box ternary complex (PDB code: 1C9B32) and yeast TFIIA/TBP/TATA box complex (PDB code: 1RM135). TFIIB ribbon domain is modeled onto the Pol II surface based on the Pol II-TFIIB co crystal (PDB code: 1R5U), and the magenta sphere represents the zinc atom. TFIIB and TBP are shown as yellow and green backbone models, respectively. The two subunits of TFIIA are colored orange (Toa1) and magenta (Toa2). The DNA strands flanking the TATA box (recognized by TBP) is extended from the human TFIIBc/TBP/DNA x-ray structure using the straight B-form DNA. The DNA non-template strand is colored pink and the template strand is colored light blue. DNA base pair −12 (numbering based on the Adenovirus Major Late promoter used in the crystal structure), the site of DNA strand melting for Open complex formation, is colored dark red for the template strand and dark blue for the non-template strand, respectively. The DNA extends from promoter position −47 to +18 using the numbering of the Adenovirus Major Late promoter where +1 base is the transcription start and the TATA box sequence starts at −31. The Pol II surface is colored white except for Rpb9 (orange). Bpa positions crosslinked to TFIIB are colored green. Bpa positions crosslinked to TFIIF and TFIIE are colored purple and light blue, respectively. (b) Structural model is the same as (a). The locations of TFIIF dimerization domain (Tfg1n+ Tfg2n) and TFIIE (Tfa1+Tfa2) are shown with semi-transparent light green and magenta ovals, respectively.

Our results, taken together with previous findings, show the close interaction of the general factors poised over the active site cleft where they likely cooperate in post recruitment steps. Biochemical assays have demonstrated that TFIIB, TFIIF, and TFIIE bind directly to Pol II37. The structure of the TFIIB-Pol II complex demonstrated that the TFIIB B-finger domain is located within the active site cleft of Pol II10. Photocrosslinkers positioned on the TFIIB B-finger, linker and core domains show that these regions are in close proximity to TFIIF in the PIC, locating part of TFIIF within the active site cleft9. Our new results show that the TFIIF dimerization domain is positioned above the cleft, adjacent to Rpb9, and directly across the cleft from TFIIE. Previous experiments showed that the TFIIH helicase XPB (yeast Rad25) is located near promoter DNA just downstream from the location of TFIIE19,23. Thus, the combined results reveal the close association of TFIIB, TFIIF, TFIIE, and XPB and suggest important protein-protein interactions between these factors that are involved in post-recruitment steps. These steps would involve initial melting of the promoter DNA strands, insertion of the single stranded template strand into the active site of Pol, and translocation of the template strand through the active site of the enzyme until the transcription start site is recognized.

Mutations in TFIIB, TFIIF, Rpb1, 2, and 9 that alter the accuracy of transcription start site selection have all been genetically identified3,4,6,7,11,33,38. It has been difficult to explain how mutations in Rpb2 lobe/protrusion and Rpb9 (Figs. 5-7), located distant from the Pol II active site, could affect this process. Our new results, in combination with previous studies, suggest that these factors are all connected by a protein-protein interaction network extending from the Pol II Rpb1/Rpb9 jaw into the active site. Rpb9 is located adjacent to TFIIF, and part of TFIIF is located in the active site cleft adjacent to the TFIIB B-finger. We suggest that mutations in Rpb2 and Rpb9 affect the conformation and/or activity of TFIIF in transcription start site selection. Since TFIIF is closely associated with the B-finger, and the TFIIB B-finger was proposed to recognize the initiation sequence in the template strand, it is possible that TFIIF could directly or indirectly influence this DNA sequence recognition or that TFIIB could function indirectly by influencing TFIIF activity. Interestingly, mutations in TFIIF, Rpb9, and Rpb2 have opposite effects compared with mutations in Rpb1 and TFIIB. The TFIIF, Rpb9, and Rpb2 mutations cause Pol II to select more upstream transcription start sites while Rpb1 and TFIIB mutations cause Pol II to prefer more downstream transcription start sites. Understanding the effects of these mutations and the mechanism of transcription start site selection will await further biochemical and structural studies.

A model for initiation that is consistent with our results and with previous findings19 is the following: After PIC formation, torsional strain in promoter DNA caused by the XPB helicase would allow insertion of residues from TFIIF and/or TFIIE into promoter DNA to initiate and stabilize formation of the single-stranded bubble. This would lead to insertion of the single-stranded DNA into the active site of the enzyme by an as yet unknown mechanism. In a mechanism somewhat analogous to the model proposed for bacterial RNA Pol scrunching39,40, single-stranded DNA would be fed through the active site of Pol II while it is still situated at the promoter and associated with the other general factors until a suitable initiation sequence is encountered. Unlike the bacterial scrunching mechanism, the movement of single-stranded DNA is likely not driven by abortive initiation but perhaps by the helicase and ATP hydrolysis. The initiation site may be recognized by segments of TFIIB, TFIIF, and Pol II, leading to transcription start site recognition. To transition to the productive elongation mode, at a minimum, the B-finger must exit from the RNA exit channel to allow elongation and exit of the growing RNA chain from Pol II15. In addition, Pol II must break its contacts with the general factors and promoter DNA so that it can begin movement into the gene coding sequence. More details of this process and testing different aspects of the model will require trapping the initiation complex at intermediate states to allow structural and biochemical characterization of individual steps in the initiation process.

METHODS

Yeast plasmids, strains and Antisera

Plasmids, strains and antisera used for this study are listed in Supplementary Methods.

Yeast nuclear extracts and in vitro transcription assay

Yeast nuclear extracts and in vitro transcription assays were as described previously41, and the protocol can be found in the website (www.fhcrc.org/science/labs/hahn). For growing yeast culture in YPD containing p-Benzoyl-L-phenylalanine (Bpa; Bachem), the medium is prepared by adding 2.5 ml Bpa (100 mM in 1M HCl) and an equal volume of 1M NaOH to each 1-Liter of YPD before inoculation with a saturated culture.

Pol II immobilized template assay for PIC formation and photocrosslinking

Immobilized template assay for PIC formation was performed as described previously41, and the protocol can be found in the website (www.fhcrc.org/science/labs/hahn). Gal4 VP16 and nuclear extracts prepared from the amber strain grown in medium containing Bpa were used to assemble PICs on immobilized DNA templates containing the yeast HIS4 promoter and a single upstream Gal4 binding site. After washing to remove nonspecific protein binding, UV irradiation was applied to the immobilized PICs in a Spectrolinker XL-1500 (Spectronics) UV oven with a total energy of 15,000 μJ cm−2 (∼5 min). The UV-irradiated PICs were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western Blot.

Identification of the crosslinking target

Identification of the crosslinking target using Western analysis was based on visualization of the protein band simultaneously responsive to antibodies against the Bpa-carrying protein and the crosslinked polypeptides. For example, anti-TFIIB (rabbit polyclonal) and anti-Rpb1 CTD (8WG16; mouse monoclonal) antibodies were used for the TFIIB-Bpa study in which the Western blot was visualized with fluorescent dye labeled secondary antibodies against respective primary antibodies (Fig. 1d). Similarly, anti-Myc antibody was used to reveal Myc epitope tagged Rpb2 in Rpb2-Bpa crosslinking study, and the crosslinked polypeptides Rpb1, TFIIB, and Tfg2 were identified with respective polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3c). The same strategy was applied to identify Rpb1-Tfa2 crosslinking by using anti-Myc (Rpb1) and anti-Tfa2 antibodies (Fig. 4d). For identifying a crosslinking target such as Tfg1 that has no polyclonal antiserum, two mixing methods were utilized. In the first method, the recombinant TFIIF (320 ng) containing Flag epitope tagged Tfg1 (see below) was added into the nuclear extract (480 μg) of Rpb2 amber strain and used in immobilized template assay and photocrosslinking. The resulting sample was analyzed by Western analysis using anti-Flag antibody to confirm the identity of the crosslinked protein Tfg1 (Fig. 3b). In the second method, the nuclear extract containing the Flag epitope tagged Tfg1 was pre-mixed with the nuclear extract of the Rpb2 amber strain with 1:1 ratio to a total of 480 μg of proteins in the immobilized template assay, followed by photocrosslinking and Western analysis using anti-Flag antibody to identify Tfg1 (Supplementary Fig. 1). This nuclear extract mixing method was also applied to validate Rpb1-Tfa1 crosslinking (Fig. 4C).

TFIIF mutant plasmids

To circumvent problems with the cloning and expression of the S. cerevisiae TFG1 gene, the gene encoding S. mikatae TFG1 (which completely complements TFG1 function in S. cerevisiae) was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA prepared from S. mikatae and the resulting 2.7-kbp DNA fragment was cloned through A-tail ligation to the pETSUMO vector (Invitrogen) with a SUMO protease cleavage site inserted before SmTfg1 residue 1. Subsequently, the 3.1-kbp Sph1I/SacI DNA fragment containing 6xHis-SUMO-SmTfg1 was subcloned into the pETDuet-1 vector (Novagen), followed by cloning of the 1.2-kbp PCR-generated S. cerevisiae TFG2 (ScTfg2) DNA fragment into the second polylinker region between XhoI and AvrII sites. The resulting plasmid was subjected to oligonucleotide-directed phagemid mutagenesis to mutate all endogenous cysteines in both SmTfg1 and ScTfg2 to non-Cys residues. The resulting plasmid pHCf601 contains the following mutations: SmTfg1(C611S, C717S) and ScTfg2(C219A, C222A, C322S). All cys substitutions in the Tfg1 dimerization domain were generated using phagemid mutagenesis of pHCf601.

Co-immune precipitation of Tfg1 and Tfg2 dimerization domain peptide fragments

Flag-tagged SmTfg1 and untagged ScTfg2 N-terminal peptide fragments were generated by in vitro translation using PCR generated DNA templates and reticulocyte lysate (TnT T7 Quick; Promega). Each set of SmTfg1 and ScTfg2 polypeptides (Supplementary Fig. 3c; IVT) were co-expressed in a 50-μL coupled T7 transcription/translation reactions. The in vitro translation products were mixed with 20 μg Anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) pre-equilibrated with potassium acetate transcription buffer containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA and 0.05% (v/v) NP-40 and was incubated at 4 °C for 2 hr. The anti-Flag gel beads with bound TFIIF peptide fragments were washed 3 times with 400 μl transcription buffer containing 0.05% NP-40 and 150 mM potassium acetate final concentration. Immune precipitated TFIIF peptide fragments were eluted with 100 μl 1mg ml−1 triple Flag peptide (Sigma), precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (final concentration 10% v/v), and were analyzed by Western blotting using the LI-COR Bioscience Odyssey infrared imaging system.

TFIIF Purification

TFIIF was purified as detailed in Supplementary Methods.

Attachment of protein cleavage reagent FeBABE to TFIIF cys mutants

The procedure for labeling the TFIIF cys mutants with FeBABE (Dojindo) was similar to that for TFIIB described previously8. TFIIF mutant samples were first subjected to a procedure to remove DTT present in the purification buffer using a NAP-5 desalting column (GE Healthcare). The protein samples were then incubated with FeBABE, followed by removal of the unincorporated FeBABE by a second NAP-5 column. Labeled samples were frozen and stored at −70°C until used in hydroxyl radical assay. Labeling and sample storage buffer contained 300 mM potassium acetate, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8).

Hydroxyl radical cleavage assay and determination of the FeBABE cleavage sites in Rpb1 and Rpb2

Hydroxyl radical probing experiments were conducted using the method described in previous TFIIB work8. Yeast nuclear extracts, Gal4-VP16 activator, and FeBABE conjugated TFIIF cys mutants were used in the Pol II immobilized template assay to form PICs on DNA templates attached to magnetic beads (see above). The amount of FeBABE conjugated TFIIF used in a 100 μL PIC formation assay was 800 ng. After PIC formation on immobilized templates, Fe-EDTA was activated to generate hydroxyl radicals as described previously. Cleavage fragments were visualized by Western blot and the LI-COR Bioscience Odyssey infrared imaging system. Accurate determination of the molecular size of the FeBABE cleavage fragments and the corresponding cut sites within proteins has been described previously8. For each calculated cut site, a range of 9 amino acids (centered at the cut site) was highlighted on the Pol II surface based on the estimated precision of the molecular size determination.

Pol II-TFIIF binding assay

Nuclear extracts from yeast strains containing wild-type or mutant Rpb2 with C-terminal flag tag were used for immune precipitation. Nuclear extract (480 μg) was mixed with 20 μg Anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) in 100 μl potassium acetate transcription buffer (see above; in vitro transcription) with additional 0.1% (w/v) BSA and 0.05% (v/v) NP-40 and was incubated at 4 °C for 2 hr. Immune precipitated Pol II was washed 3 times with 400 μl transcription buffer containing 0.1% BSA and 0.05% NP-40. Samples were washed three more times with 400 μl of transcription buffer containing 550 mM potassium acetate and 0.05% NP-40. The anti-Flag gel beads with bound Pol II-TFIIF complex were eluted with 100 μl 1mg ml−1 triple Flag peptide (Sigma) and were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid (final concentration 10% v/v). Polypeptides retained from co-immune precipitation were analyzed by Western analysis and visualized using the LI-COR Bioscience Odyssey infrared imaging system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Gail Miller, Beth Moorefield, Neeman Mohibullah, Ted Young, and other members of the Hahn lab for their comments and suggestions throughout the course of this work. We thank Jesse Eichner (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) for assistance with TFIIF purification. We thank Peter Schultz, Jason Chin, and Ashton Cropp (The Scripps Research Institute) for the non-natural aa tRNA/synthetase plasmid and advice on non-natural amino acid use, and Beth Moorefield and Neeman Mohibullah for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Grant 5R01GM053451 from the National Institutes of Health to S.H.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This PDF receipt will only be used as the basis for generating PubMed Central (PMC) documents. PMC documents will be made available for review after conversion (approx. 2−3 weeks time). Any corrections that need to be made will be done at that time. No materials will be released to PMC without the approval of an author. Only the PMC documents will appear on PubMed Central -- this PDF Receipt will not appear on PubMed Central.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Hahn S. Structure and mechanism of the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:394–403. doi: 10.1038/nsmb763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giardina C, Lis JT. DNA melting on yeast RNA polymerase II promoters. Science. 1993;261:759–62. doi: 10.1126/science.8342041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto I, Wu WH, Na JG, Hampsey M. Characterization of sua7 mutations defines a domain of TFIIB involved in transcription start site selection in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30569–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun ZW, Hampsey M. Identification of the gene (SSU71/TFG1) encoding the largest subunit of transcription factor TFIIF as a suppressor of a TFIIB mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3127–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen BS, Hampsey M. Functional interaction between TFIIB and the Rpb2 subunit of RNA polymerase II: implications for the mechanism of transcription initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3983–91. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3983-3991.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghazy MA, Brodie SA, Ammerman ML, Ziegler LM, Ponticelli AS. Amino acid substitutions in yeast TFIIF confer upstream shifts in transcription initiation and altered interaction with RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10975–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10975-10985.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freire-Picos MA, Krishnamurthy S, Sun ZW, Hampsey M. Evidence that the Tfg1/Tfg2 dimer interface of TFIIF lies near the active center of the RNA polymerase II initiation complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5045–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen HT, Hahn S. Binding of TFIIB to RNA polymerase II: Mapping the binding site for the TFIIB zinc ribbon domain within the preinitiation complex. Mol Cell. 2003;12:437–47. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HT, Hahn S. Mapping the location of TFIIB within the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex: a model for the structure of the PIC. Cell. 2004;119:169–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bushnell DA, Westover KD, Davis RE, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: an RNA polymerase II-TFIIB cocrystal at 4.5 Angstroms. Science. 2004;303:983–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1090838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun ZW, Tessmer A, Hampsey M. Functional interaction between TFIIB and the Rpb9 (Ssu73) subunit of RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2560–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.13.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziegler LM, Khaperskyy DA, Ammerman ML, Ponticelli AS. Yeast RNA polymerase II lacking the Rpb9 subunit is impaired for interaction with transcription factor IIF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48950–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holstege FC, Fiedler U, Timmers HT. Three transitions in the RNA polymerase II transcription complex during initiation. Embo J. 1997;16:7468–80. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dvir A. Promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:208–223. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pal M, Ponticelli AS, Luse DS. The role of the transcription bubble and TFIIB in promoter clearance by RNA polymerase II. Mol Cell. 2005;19:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer P, et al. Architecture of RNA polymerase II and implications for the transcription mechanism. Science. 2000;288:640–9. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Complete, 12-subunit RNA polymerase II at 4.1-A resolution: implications for the initiation of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6969–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1130601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armache KJ, Kettenberger H, Cramer P. Architecture of initiation-competent 12-subunit RNA polymerase II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6964–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1030608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller G, Hahn S. A DNA-tethered cleavage probe reveals the path for promoter DNA in the yeast preinitiation complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:603–10. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TK, et al. Trajectory of DNA in the RNA polymerase II transcription preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert F, et al. Wrapping of promoter DNA around the RNA polymerase II initiation complex induced by TFIIF. Mol Cell. 1998;2:341–51. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80278-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douziech M, et al. Mechanism of promoter melting by the xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group B helicase of transcription factor IIH revealed by protein-DNA photo-cross-linking. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8168–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8168-8177.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim TK, Ebright RH, Reinberg D. Mechanism of ATP-dependent promoter melting by transcription factor IIH. Science. 2000;288:1418–22. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung WH, et al. RNA polymerase II/TFIIF structure and conserved organization of the initiation complex. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1003–13. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chin JW, et al. An expanded eukaryotic genetic code. Science. 2003;301:964–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1084772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kauer JC, Erickson-Viitanen S, Wolfe HR, Jr., DeGrado WF. p-Benzoyl-L-phenylalanine, a new photoreactive amino acid. Photolabeling of calmodulin with a synthetic calmodulin-binding peptide. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:10695–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Giuliodori S, et al. A composite upstream sequence motif potentiates tRNA gene transcription in yeast. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warfield L, Ranish JA, Hahn S. Positive and negative functions of the SAGA complex mediated through interaction of Spt8 with TBP and the N-terminal domain of TFIIA. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1022–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.1192204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fishburn J, Mohibullah N, Hahn S. Function of a eukaryotic transcription activator during the transcription cycle. Mol Cell. 2005;18:369–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves WM, Hahn S. Targets of the Gal4 transcription activator in functional transcription complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9092–102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.20.9092-9102.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikolov DB, et al. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature. 1995;377:119–28. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai FT, Sigler PB. Structural basis of preinitiation complex assembly on human pol II promoters. Embo J. 2000;19:25–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hekmatpanah DS, Young RA. Mutations in a conserved region of RNA polymerase II influence the accuracy of mRNA start site selection. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5781–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaiser F, Tan S, Richmond TJ. Novel dimerization fold of RAP30/RAP74 in human TFIIF at 1.7 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:1119–27. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geiger JH, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–6. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HT, Legault P, Glushka J, Omichinski JG, Scott RA. Structure of a (Cys3His) zinc ribbon, a ubiquitous motif in archaeal and eucaryal transcription. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1743–52. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bushnell DA, Bamdad C, Kornberg RD. A minimal set of RNA polymerase II transcription protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20170–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berroteran RW, Ware DE, Hampsey M. The sua8 suppressors of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encode replacements of conserved residues within the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II and affect transcription start site selection similarly to sua7 (TFIIB) mutations. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:226–37. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapanidis AN, et al. Initial transcription by RNA polymerase proceeds through a DNA-scrunching mechanism. Science. 2006;314:1144–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1131399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Revyakin A, Liu C, Ebright RH, Strick TR. Abortive initiation and productive initiation by RNA polymerase involve DNA scrunching. Science. 2006;314:1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1131398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ranish JA, Yudkovsky N, Hahn S. Intermediates in formation and activity of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex: holoenzyme recruitment and a postrecruitment role for the TATA box and TFIIB. Genes Dev. 1999;13:49–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD. Structural basis of transcription: separation of RNA from DNA by RNA polymerase II. Science. 2004;303:1014–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1090839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–96. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.