Abstract

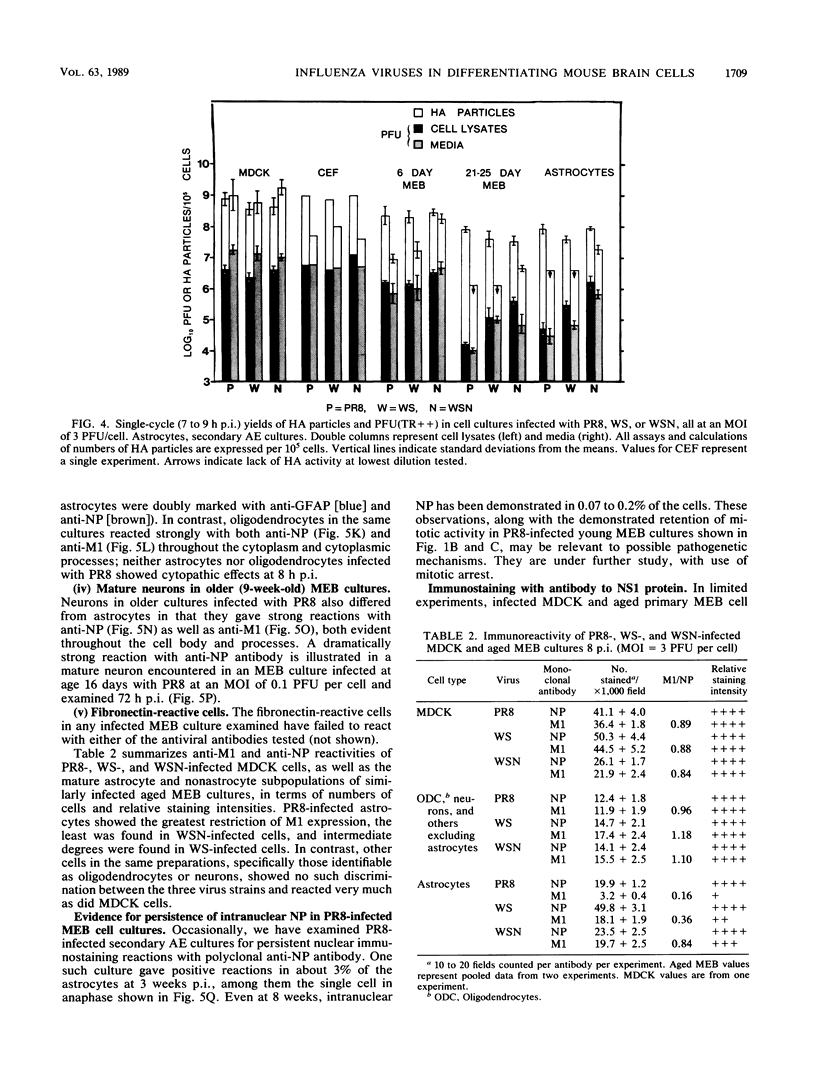

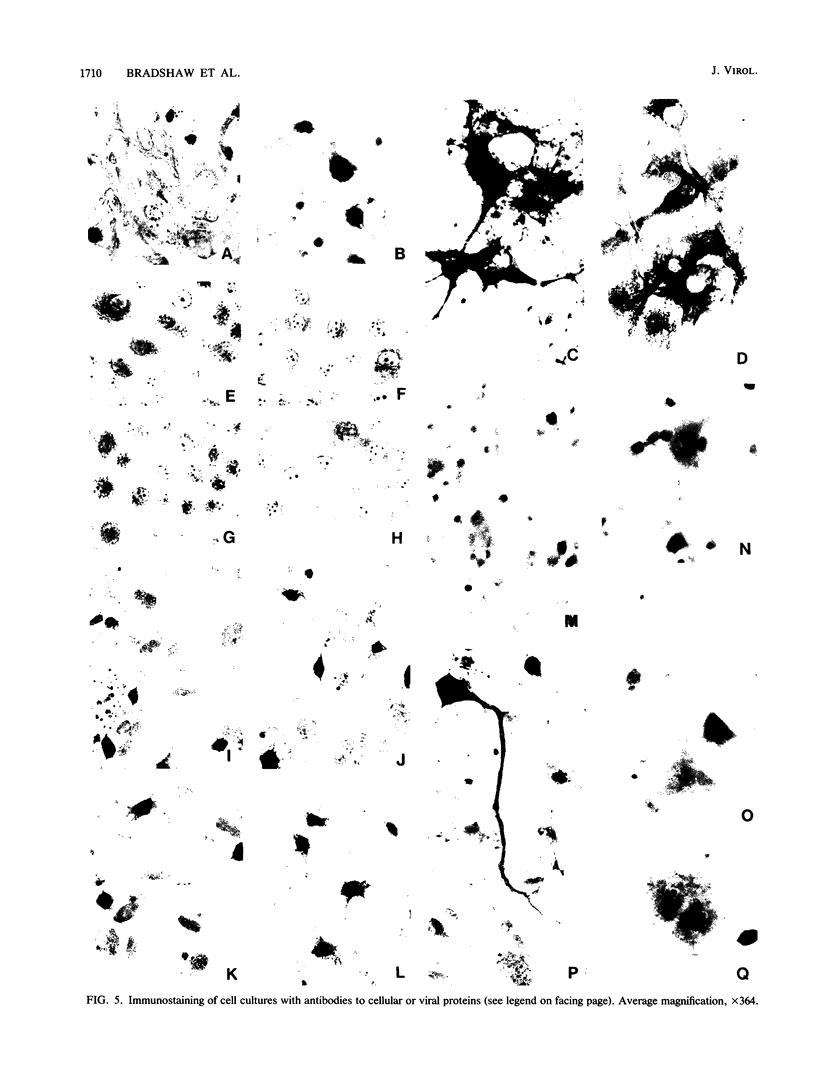

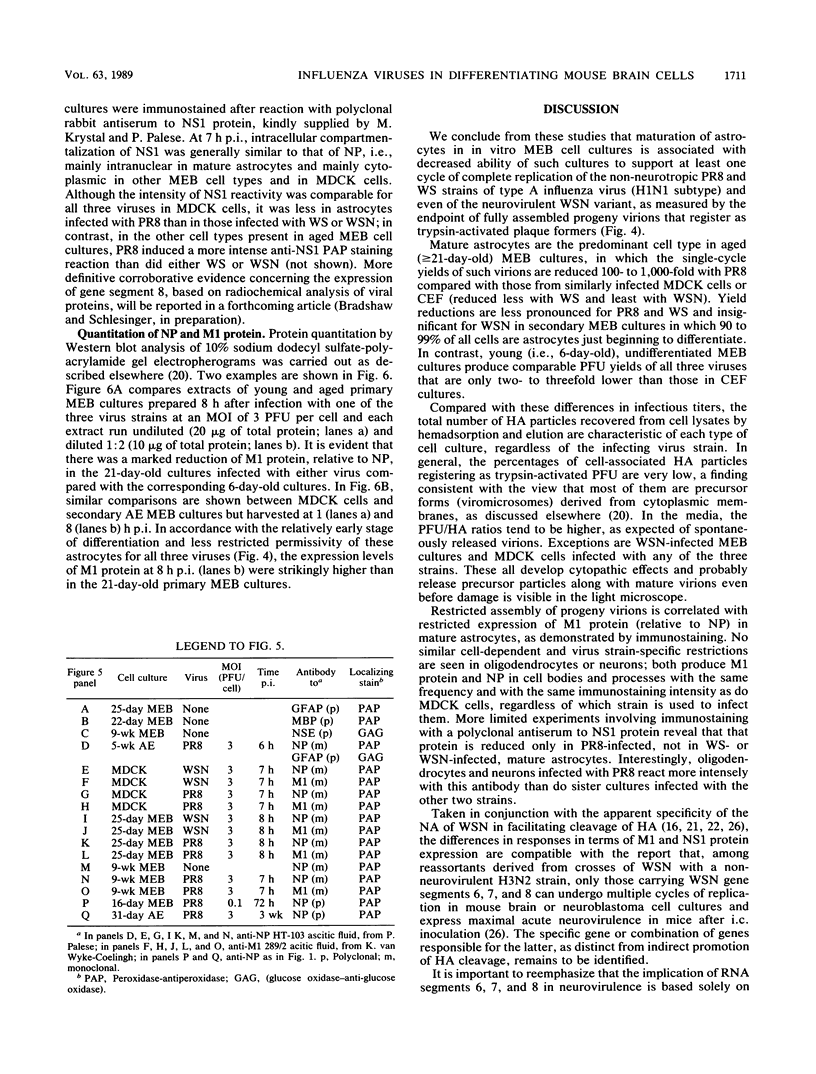

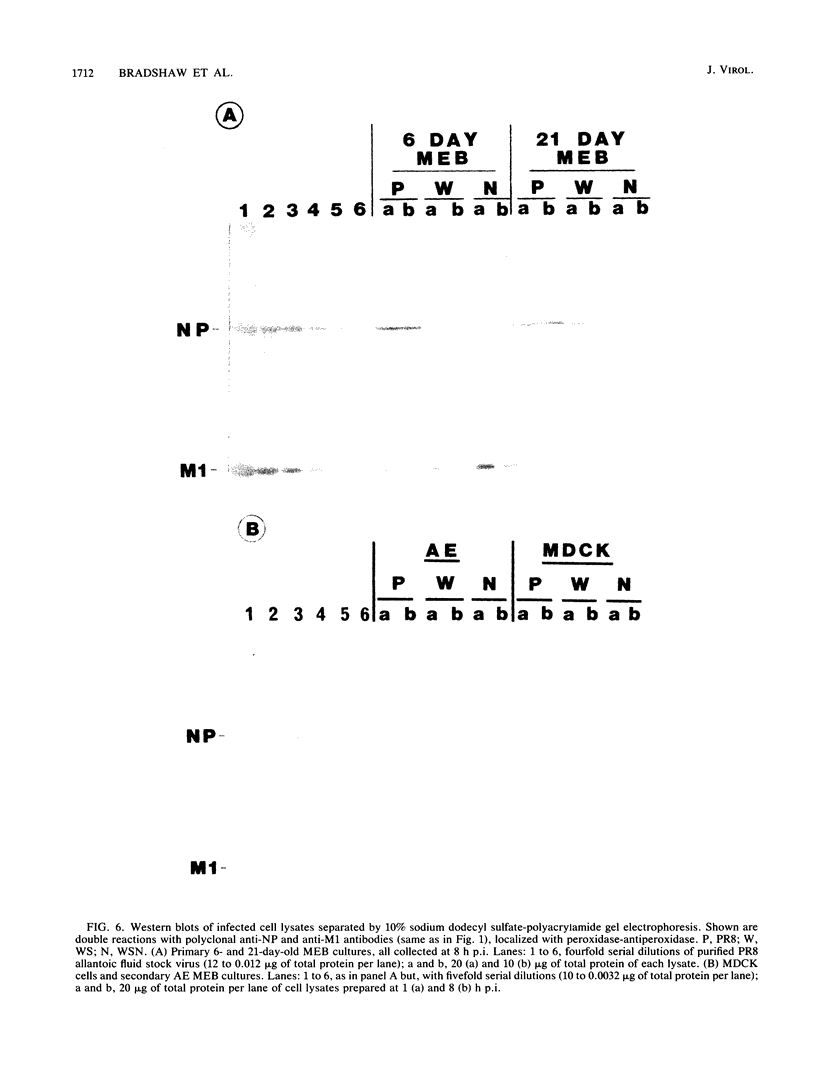

The responses of mouse embryo brain (MEB) cell cultures and of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells and chicken embryo fibroblasts to infection with A/PR/8/34 (PR8), A/WS/33 (WS), or the neurovirulent WSN variant were compared in terms of (i) single-cycle yields of hemagglutinating and associated neuraminidase (NA) activities and plaque-forming particles, the latter with or without trypsin activation [PFU(TR++) or PFU(TR--), respectively], and (ii) expression of nucleoprotein (NP), M1, and NS1 protein, determined for specific cell types by immunostaining, for whole culture lysates by Western blot analysis of NP and M1. Primary MEB cultures grown in serum-enriched medium were infected after 6 days (young), when none of the cells reacted specifically and exclusively with any of the nerve cell marker antibodies used, or after greater than or equal to 21 days (aged), when astrocytes (the predominant cell type), neurons, and oligodendrocytes were morphologically and immunologically mature. Secondary astrocyte-enriched cultures were used when they contained 90 to 99% of their cells as astrocytes at an early stage of differentiation. By all criteria, young MEB cultures were only marginally less permissive for each of the three viruses than were chicken embryo fibroblasts or Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Aged MEB cultures, by comparison, produced undiminished NP, hemagglutinin, and neuraminidase, but yields of PFU(TR++) and expression of M1 protein (relative to NP) were reduced for all three viruses, most for PR8 and least for WSN; relative reduction of NS1 protein was demonstrable only in PR8-infected aged cultures. Immunostaining revealed low levels of M1 and NS1 expression only in astrocytes, not in oligodendrocytes and neurons. In PR8-infected mature astrocytes, NP accumulated in the nucleus; it persisted in some cells for at least 8 weeks after infection. The presence of NP did not seem to interfere with cell division. Secondary MEB cultures containing 90 to 99% immature astrocytes were less restricted than were aged primary cultures. Thus, it appears that reduced permissivity of nerve cell cultures, as measured in this study, is most closely correlated with advancing differentiation and maturity of astroglial cells. Assembled virions, including those that score as PFU(TR++) in restricted cultures (e.g., PR8-infected aged MEB), may be mainly products of mature oligodendrocytes and neurons.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- AMINOFF D. Methods for the quantitative estimation of N-acetylneuraminic acid and their application to hydrolysates of sialomucoids. Biochem J. 1961 Nov;81:384–392. doi: 10.1042/bj0810384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor N. W., Li Y., Ye Z. P., Wagner R. R. Transient expression and sequence of the matrix (M1) gene of WSN influenza A virus in a vaccinia vector. Virology. 1988 Apr;163(2):618–621. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90303-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell B. A., Smith M. A., Kean D. M., McGhee C. N., MacDonald H. L., Miller J. D., Barnett G. H., Tocher J. L., Douglas R. H., Best J. J. Brain water measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Correlation with direct estimation and changes after mannitol and dexamethasone. Lancet. 1987 Jan 10;1(8524):66–69. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. A., Downs E. C., Primus F. J. An unlabeled antibody method using glucose oxidase-antiglucose oxidase complexes (GAG): a sensitive alternative to immunoperoxidase for the detection of tissue antigens. J Histochem Cytochem. 1982 Jan;30(1):27–34. doi: 10.1177/30.1.7033369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois-Dalcq M., Rentier B., Hooghe-Peters E., Haspel M. V., Knobler R. L., Holmes K. Acute and persistent viral infections of differentiated nerve cells. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Sep-Oct;4(5):999–1014. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.5.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G., Leutz A., Schachner M. Cultivation of immature astrocytes of mouse cerebellum in a serum-free, hormonally defined medium. Appearance of the mature astrocyte phenotype after addition of serum. Neurosci Lett. 1982 Apr 26;29(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henle G., Henle W. NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS IN MICE FOLLOWING INTRACEREBRAL INOCULATION OF INFLUENZA VIRUSES. Science. 1944 Nov 3;100(2601):410–411. doi: 10.1126/science.100.2601.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honegger P., Richelson E. Biochemical differentiation of mechanically dissociated mammalian brain in aggregating cell culture. Brain Res. 1976 Jun 11;109(2):335–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90534-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koolen M. J., Buchmeier M. J. Experimental models of virus attenuation and demyelinating disease. Microbiol Sci. 1986 Mar;3(3):68–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensson K., Norrby E. Persistence of RNA viruses in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:159–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIMS C. A. An analysis of the toxicity for mice of influenza virus. I. Intracerebral toxicity. Br J Exp Pathol. 1960 Dec;41:586–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima S., Sugiura A. Neurovirulence of influenza virus in mice. II. Mechanism of virulence as studied in a neuroblastoma cell line. Virology. 1980 Mar;101(2):450–457. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHLESINGER R. W. Incomplete growth cycle of influenza virus in mouse brain. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1950 Jul;74(3):541–548. doi: 10.3181/00379727-74-17966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHLESINGER R. W. The relation of functionally deficient forms of influenza virus to viral development. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1953;18:55–59. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1953.018.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger R. W., Bradshaw G. L., Barbone F., Reinacher M., Rott R., Husak P. Role of hemagglutinin cleavage and expression of M1 protein in replication of A/WS/33, A/PR/8/34, and WSN influenza viruses in mouse brain. J Virol. 1989 Apr;63(4):1695–1703. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1695-1703.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura A., Ueda M. Neurovirulence of influenza virus in mice. I. Neurovirulence of recombinants between virulent and avirulent virus strains. Virology. 1980 Mar;101(2):440–449. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERNER G. H., SCHLESINGER R. W. Morphological and quantitative comparison between infectious and non-infectious forms of influenza virus. J Exp Med. 1954 Aug 1;100(2):203–216. doi: 10.1084/jem.100.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]