Abstract

AIMS

To investigate the effect of imatinib on the pharmacokinetics of a CYP2D6 substrate, metoprolol, in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). The pharmacokinetics of imatinib were also studied in these patients.

METHODS

Patients (n = 20) received a single oral dose of metoprolol 100 mg on day 1 after an overnight fast. On days 2–10, imatinib 400 mg was administered twice daily. On day 8, another 100 mg dose of metoprolol was administered 1 h after the morning dose of imatinib 400 mg. Blood samples for metoprolol and α-hydroxymetoprolol measurement were taken on study days 1 and 8, and on day 8 for imatinib.

RESULTS

Of the 20 patients enrolled, six patients (30%) were CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers (IMs), 13 (65%) extensive metabolizers (EMs), and the CYP2D6 status in one patient was unknown. In the presence of 400 mg twice daily imatinib, the mean metoprolol AUC was increased by 17% in IMs (from 1190 to 1390 ng ml−1 h), and 24% in EMs (from 660 to 818 ng ml−1 h). Patients classified as CYP2D6 IMs had an approximately 1.8-fold higher plasma metoprolol exposure than those classified as EMs. The oral clearance of imatinib was 11.0 ± 2.0 l h−1 and 11.8 ± 4.1 l h−1 for CYP2D6 IMs and EMs, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Co-administration of a high dose of imatinib resulted in a small or moderate increase in metoprolol plasma exposure in all patients regardless of CYP2D6 status. The clearance of imatinib showed no difference between CYP2D6 IMs and EMs.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, exhibits a competitive inhibition on the CYP450 2D6 isozyme with a Ki value of 7.5 μm. However, the clinical significance of the inhibition and its relevance to 2D6 polymorphisms have not been evaluated. The pharmacokinetics of imatinib have been well studied in Caucasians, but not in a Chinese population.

Metoprolol, a CYP2D6 substrate, has different clearances among patients with different CYP2D6 genotypes. It is often used as a CYP2D6 probe substrate for clinical drug–drug interaction studies.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Co-administration of imatinib at 400 mg twice daily increased the plasma AUC of metoprolol by approximately 23% in 20 Chinese patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), about 17% increase in CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers (IMs) (n = 6), 24% in extensive metabolizers (EMs) (n = 13), and 28% for the subject with unknown 2D6 status (n = 1) suggesting that imatinib has a weak to moderate inhibition on CYP2D6 in vivo.

The clearance of imatinib in Chinese patients with CML showed no difference between CYP2D6 IMs and EMs, and no major difference from Caucasian patients with CML based on data reported in the literature.

Keywords: CML, CYP2D6, Glivec, imatinib, metoprolol, pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Imatinib (formerly STI571; Gleevec®) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor with proven efficacy in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) [1, 2]. Imatinib has favourable pharmacokinetic (PK) characteristics, including rapid and complete oral bioavailability (98%) and a proportional dose-exposure relationship [3, 4]. Its terminal half-life is approximately 20 h, allowing for once daily dosing. Despite a favourable PK profile, drug–drug interactions may occur because imatinib has been shown to interact with certain cytochrome P450 (CYP450) metabolizing enzymes. Imatinib undergoes metabolism mainly through the major isozyme CYP3A4, although CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 also contribute to a minor extent [3]. CGP74588 is a major metabolite of imatinib, which has a similar biological activity and represents approximately 20% of the parent drug plasma concentration in patients. Drugs that inhibit or induce the CYP3A4 isozyme have been shown to alter imatinib PK exposure [5–9]. In vitro studies show that imatinib is a competitive inhibitor of 3A4/5 and 2D6 isozymes with Ki values of 8 and 7.5 μm, respectively [3]. In patients with CML, imatinib 400 mg four times a day increased the plasma exposure of simvastatin, a CYP3A4 substrate, by approximately three-fold [10]. The present study investigated the effect of imatinib on drug exposure of metoprolol, a CYP2D6 substrate in CML patients with known CYP2D6 phenotypes.

Metoprolol, a selective β1-adrenoceptor antagonist, is a well-investigated drug with widespread clinical use. It undergoes significant first pass metabolism with approximately 85% of the dose converted mostly into an inactive metabolite, α-hydroxymetoprolol, via CYP2D6 [11–13]. Metoprolol is often used as a CYP2D6 probe substrate for clinical drug–drug interaction studies. The CYP2D6 gene is highly polymorphic; over 70 distinct alleles and allele variants have been described [14, 15], which may differ substantially in their ability to metabolize CYP2D6 probe substrates. The CYP2D6 ultra-rapid metabolizers (UMs), extensive metabolizers (EMs), intermediate metabolizers (IMs), and poor metabolizers (PMs) compose about 3–5%, 70–80%, 10–17%, and 3–7% of the Caucasian population, respectively [14–17]. In the Chinese population, CYP2D6 PMs are infrequent, approximately 1% of the population (vs. 3–7% in Caucasians and 2–7% in African Americans) [16–20]. In the present study 20 patients with CML were genotyped to participate in the drug–drug interaction study between imatinib and metoprolol. The effect of CYP2D6 phenotype status on the extent of the interaction was also explored.

Methods

This was an open-label, one-sequence study of 20 patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) early phase CML. The study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ruijin Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to enrolment into the study.

Patients

Male or female Chinese patients (≥18 years of age) with histologically or cytologically confirmed Ph+ CML who were imatinib naïve, were eligible for the study. Patients were required to have Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance status ≤3. Patients with significant hepatic, renal, respiratory or cardiac abnormalities were excluded. Patients receiving CYP2D6 inhibitors or with any surgical or medical condition which might significantly alter the pharmacokinetics of metoprolol or imatinib were also excluded.

The CYP2D6 genotype status of patients was identified using the AmpliChip CYP450 Test (Roche Molecular System) [21]. The assessment was performed by MDS Pharma Services, Beijing, China, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Using this test, patients can be classified into the following phenotype groups: ultra-rapid metabolizers (UMs) who carry multiple copies of functional alleles producing excess enzymatic activity; extensive metabolizers (EMs) who possess at least one, and no more than two normal functional alleles; intermediate metabolizers (IMs) who possess one reduced activity allele and one null allele; and poor metabolizers (PMs) who carry two mutant alleles which result in complete loss of enzyme activity [22].

Study design

Patients received a single oral dose of metoprolol 100 mg (as two Betaloc® 50 mg tablets, AstraZeneca Co., Wuxi New District, Jiangsu, P.R.China) on study day 1 after an overnight fast. On study days 2–10, imatinib 400 mg (as four 100 mg hard gelatin capsules) was administered twice daily for a total daily dose of 800 mg. On study day 8, an oral dose of imatinib 400 mg was given under fasting conditions, and a single oral dose of metoprolol 100 mg was administered 1 h after imatinib dosing. Lunch and dinner were served 4 h and 12 h, respectively, after drug administration on days 1 and 8.

Patients were instructed to avoid strenuous physical exercise, alcohol, xanthine (e.g. caffeine) and grapefruit containing food or beverages and St Johns wort 2 days before the study and during the study period.

Safety assessment and monitoring

Safety assessment included the collection of all adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), with their severity and relationship to study drug, and pregnancies. Regular monitoring consisted of concomitant medications and significant nondrug therapies, ECG recordings, and routine haematology, blood chemistry and urine analysis. Vital signs, physical condition and body weight were also assessed.

PK sample collection and analysis

Blood samples for determination of metoprolol and metabolite plasma concentrations were taken predose and at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h after metoprolol administration on study days 1 and 8. Blood was collected for measurement of imatinib and metabolite (CGP74588) plasma concentrations prior to the first, second and third imatinib doses (days 2 and 3 after the first metoprolol dose) and prior to the morning doses on days 7, 8, 9, and 10. A full concentration profile over the 12 h dosing interval (0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 12 h) was obtained on day 8 following the morning dose. The plasma concentrations of imatinib and CGP74588 were determined by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectronomy (LC/MS/MS). The limit of quantification was 5 ng ml−1 for both imatinib and CGP74588; the assay was fully validated [23]. The accuracy and precision were 104% ± 6% at the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) and 99% ± 5% to 108% ± 5% over the entire concentration range of 4–10 000 ng ml−1. Plasma samples were analyzed for metoprolol and its metabolite α-hydroxymetoprolol by Pharma Bio Research, Zuidlaren, the Netherlands using a validated HPLC method with fluorescence detection [24]. Using 1 ml of plasma, linearity was demonstrated over the calibration range of 1–500 ng ml−1 for metoprolol and α-hydroxymetoprolol. The total CV was below 15% (20% at the LLOQ) and the (overall) bias was within ±15% of the nominal value (± 20% at the LLOQ).

The following PK parameters for metoprolol and its metabolite α-hydroxymetoprolol were estimated using noncompartmental methods (WinNolin Pro, Version 3.2, Pharsight Corp, Mountain View, CA): area under the plasma concentration vs. time curve from time 0 to infinity (AUC(0,∝)), maximum plasma drug concentration after administration (Cmax), and time to reach maximum plasma drug concentration (tmax). The apparent total body clearance (CL/F) of metoprolol was calculated as Dose/AUC(0,∝), and its metabolic to parent drug ratio (MR) was estimated as the AUC(0,∝) ratio of α-hydroxymetoprolol to metoprolol. For imatinib and its metabolite CGP74588, Cmax, tmax, AUC(0,12 h) and CL/F (imatinib only) were calculated for the 12 h dosing interval on day 8. The MR of imatinib was also calculated as the AUC(0,12 h) ratio of CGP74588 to imatinib. The accumulation ratio (R) was calculated based on the trough concentrations of imatinib and CGP74588 determined at 12 h after the morning dose on day 8 (day 7 relative to imatinib dosing time) relative to the trough concentrating following the first imatinib dose using the following equation:

|

(1) |

where λz is the elimination rate constant and τ is the dosing interval (12 h for imatinib). The effective half-life was calculated by t1/2 = 0.693/λz.

Statistical analysis

Based on an intrapatient coefficient of variation of 20% for metoprolol AUC, it was expected that a sample size of 18 patients would provide at least 80% power in claiming no effect of imatinib on metoprolol PK parameters (AUC and Cmax) using the default no effect region (90% confidence interval [CI] of log parameter ratio within 0.8, 1.25). Descriptive statistics of metoprolol pharmacokinetic parameters included geometric and arithmetic means, standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV). Median values and ranges were provided for Tmax. Imatinib PK parameters obtained from Day 8 were summarized similarly.

Analysis of variance (anova) was used to analyze the log-transformed Cmax, AUC, and CL/F of metoprolol. For each PK parameter the model included treatment as a fixed factor and subject as a random factor. A point estimate and its 90% CI for the difference between least squares means with (test treatment) and without co-administration of imatinib (reference treatment) was calculated. This estimate and its 90% CI were antilogged to obtain the point estimate and the 90% CI for the ratio of geometric means on the untransformed scale. Absence of drug–drug interaction could be claimed if the 90% CI of the ratio of the geometric means was completely contained in (0.8, 1.25). Additionally, Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed on (untransformed) within-subject test–reference differences in metoprolol tmax.

Results

Twenty patients (16 male, four female) were enrolled and completed the study. All patients were native Chinese, with mean age of 40.5 (± 11.0) years and mean body weight of 72.1 (± 12.1) kg. A total of seven different CYP2D6 genotypes were identified, with CYP2D6*1 (28.9%), *2 (7.9%) and *10 (52.6%) being the most common alleles. Based on the CYP2D6 genotype, six (30%) patients were classified as IMs, 13 (65%) as EMs and one (5%) patient's genotype could not be determined due to technical difficulties (Table 1). No PMs or UMs were identified.

Table 1.

Patient demographics (mean ± SD) and CYP2D6 genotype/phenotype status

| Age (years) | Weight (kg) | CYP2D6 genotype | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IMs (n = 6) | 39.8 ± 6.1 | 72.3 ± 8.0 | *10/*10 (n = 5) |

| *36/*41 (n = 1) | |||

| EMs (n = 13) | 40.6 ± 13.2 | 73.7 ± 12.6 | *1/*2 (n = 1) |

| *1/*10 (n = 9) | |||

| *1/*41 (n = 1) | |||

| *2/*10 (n = 1) | |||

| *2/*5 (n = 1) | |||

| NA (n = 1) | 42 | 49 | – |

| All (n = 20) | 40.5 ± 11.0 | 72.1 ± 12.1 | – |

EMs, extensive metabolizers; IMs, intermediate metabolizers; NA, CYP2D6 status unknown.

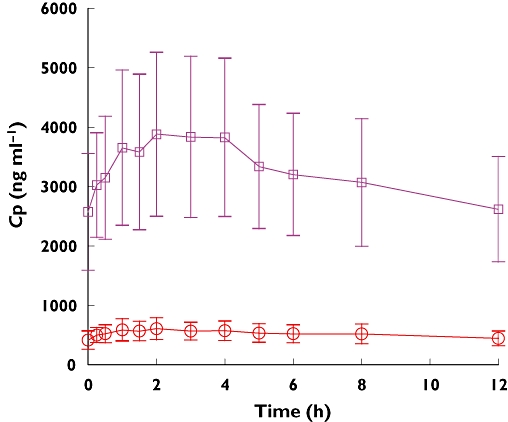

Imatinib trough plasma concentrations accumulated with time, including a rapid accumulation following the first two doses and a plateau phase between days 7 and 10 (days 6–9 relative to imatinib dosing time). The day 8 plasma concentration–time profiles of imatinib and CGP74588 are shown in Figure 1. On day 8, imatinib maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the AUC were 4245 ng ml−1 and 39 041 ng ml−1 h, respectively (Table 2). The accumulation ratios for imatinib and CGP74588 estimated based on the trough values (day 8 evening trough to day 2 evening trough) were 3.57 ± 1.24 and 4.35 ± 1.45, respectively. The effective half-lives for imatinib and CGP74588 estimated based on the accumulation factors were 25.3 ± 10.4 h and 31.8 ± 12.1 h, respectively. The metabolic ratio of imatinib, calculated as the AUC(0.12 h) ratio of CGP74588 to imatinib on day 8, was approximately 0.17. The clearance of imatinib estimated based on one dosing interval on day 8 was approximately 11.3 l h−1. No significant differences were observed in the pharmacokinetic parameters of imatinib between CYP2D6 IMs and EMs. The mean metabolic ratio of imatinib was 0.16 ± 0.04 for IMs and 0.17 ± 0.04 for EMs (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Mean (± SD) imatinib and CGP74588 plasma concentration–time profiles on day 8 (day 7 relative to imatinib dosing time) in Chinese patients with CML (n = 20). CGP74588, ( ); imatimb, (

); imatimb, ( )

)

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters (mean ± SD) of imatinib and its metabolite CGP74588 obtained for the 400 mg morning dose on day 8 in CML patients (n = 20)

| Analyte | Phenotype | Cmax (ng ml−1) | tmax (h) | AUC(0,12 h) (ng ml−1 h) | CL/F (l h−1) | MR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imatinib | IMs (n = 6) | 3920 ± 841 | 2.5 (1, 4) | 37 589 ± 8 421 | 11.0 ± 2.0 | 0.16 ± 0.04 |

| EMs (n = 13) | 4109 ± 1138 | 2 (0.5, 4) | 37 091 ± 11 163 | 11.8 ± 4.1 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | |

| NA (n = 1) | 7950 | 4 | 73 139 | 5.5 | 0.14 | |

| All (n = 20) | 4245 ± 1330 | 2 (0.5, 4) | 39 041 ± 12 700 | 11.3 ± 3.7 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | |

| CGP74588 | IMs (n = 6) | 588 ± 154 | 1.3 (1, 3) | 5 975 ± 1 652 | – | – |

| EMs (n = 13) | 656 ± 186 | 2 (0.5, 5) | 6 166 ± 1 522 | – | – | |

| NA (n = 1) | 970 | 2 | 10 426 | – | – | |

| All (n = 20) | 651 ± 186 | 2 (0.5, 4) | 6 320 ± 1 770 | – | – |

IMs, intermediate metabolizers; EMs, extensive metabolizers; NA, unknown CYP2D6 status; MR, metabolic to parent drug AUC ratio. Cmax, maximum observed concentration; tmax, time to reach Cmax (tmax presented as median and range); AUC(0,12 h), area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0–12 h; t1/2, elimination half-life; CL/F, oral clearance; MR, metabolic ratio calculated as the AUC(0,12 h) ratio of CGP74588 to imatinib.

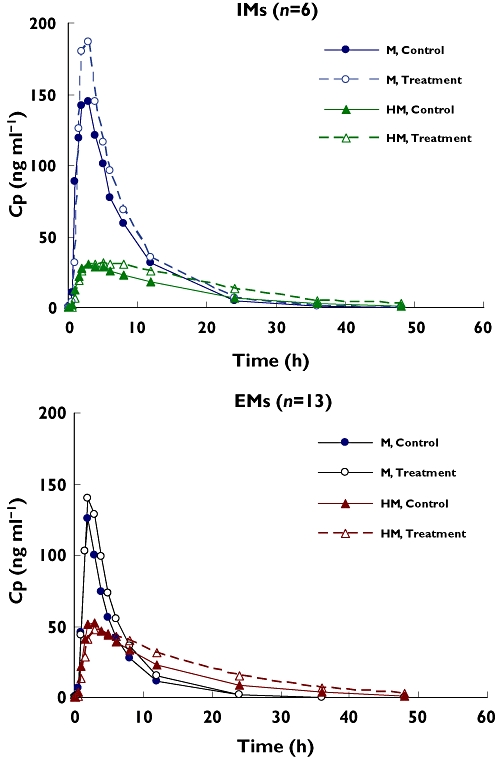

The plasma concentration–time profiles and PK parameters for metoprolol are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2. Patients classified as 2D6 IMs had a higher plasma exposure of metoprolol (1195 ng ml−1 h) than those classified as EMs (660 ng ml−1 h), an approximately 1.8-fold difference. Consequently, IMs showed a lower metabolite exposure (531 ng ml−1 h) than EMs (729 ng ml−1 h), an approximately 1.4-fold difference. The subject with an unknown 2D6 status had a low plasma exposure, 462 ng ml−1 h, more like an EM subject. However, the metabolite concentration from this particular subject was not as high as in an EM subject.

Table 3.

Metoprolol and α-hydroxymetoprolol PK parameters (mean ± SD) in patients with CML after a single 100 mg dose metoprolol alone (day 1) and in combination with imatinib (day 8) (n = 20)

| Analyte | Day | Phenotype | Cmax (ng ml−1) | tmax (h) | AUC (0,∝) (ng ml−1 h) | t½ (h) | CL/F (l h−1) | MR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | 1 | IMs (n = 6) | 177 ± 55.9 | 2 (1, 4) | 1190 ± 365 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 95 ± 44 | 0.53 ± 0.37 |

| EMs (n = 13) | 131 ± 49.2 | 2 (1.5, 3) | 660 ± 337 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 175 ± 59 | 1.32 ± 0.62 | ||

| NA (n = 1) | 76.7 | 2 | 462 | 3.6 | 216 | 1.23 | ||

| Data pooled (n = 20) | 142.2 ± 55.2 | 2 (1, 4) | 811 ± 418 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 153 ± 66 | 1.08 ± 0.65 | ||

| 8 | IMs (n = 6) | 204 ± 54.5 | 2.5 (1.5, 3.1) | 1390 ± 376 | 4.9 ± 0.7 | 78 ± 227 | 0.60 ± 0.36 | |

| EMs (n = 13) | 159 ± 48.3 | 2 (1.5, 4) | 818 ± 397 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 141 ± 48 | 1.36 ± 0.62 | ||

| NA (n = 1) | 152 | 1.5 | 591 | 3.8 | 169 | 1.46 | ||

| Data pooled (n = 20) | 171.9 ± 52.0 | 2 (1.5, 4) | 979 ± 465 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 123 ± 51 | 1.14 ± 0.64 | ||

| α-hydroxy-metoprolol | 1 | IMs (n = 6) | 33.6 ± 10.7 | 3.5 (1.5, 5) | 531 ± 109 | 9.8 ± 1.1 | ||

| EMs (n = 13) | 56.5 ± 19.2 | 2 (1.5, 3) | 729 ± 143 | 8.9 ± 1.1 | ||||

| NA (n = 1) | 53.7 | 5 | 569 | 7.3 | ||||

| Data pooled (n = 20) | 49.5 ± 19.4 | 3 (1.5, 5) | 662 ± 158 | 9.1 ± 1.7 | ||||

| 8 | IMs (n = 6) | 32.1 ± 7.6 | 4.1 (3, 8) | 751 ± 209 | 10.2 ± 2.0 | |||

| EMs (n = 13) | 49.5 ± 15.1 | 3 (2, 5) | 946 ± 174 | 10.3 ± 2.1 | ||||

| NA (n = 1) | 64 | 3 | 865 | 9.2 | ||||

| Data pooled (n = 20) | 45.0 ± 15.6 | 3 (2, 8) | 883 ± 197 | 10.2 ± 1.9 |

IMs, intermediate metabolizers; EMs, extensive metabolizers; NA, unknown CYP2D6 status; MR, metabolic to parent drug AUC ratio. Cmax, maximum observed concentration; tmax, time to reach Cmax (tmax presented as median and range); AUC(0,∝), area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; t1/2, elimination half-life; CL/F, oral clearance; MR, metabolic ratio calculated as the AUC(0,∝) ratio of α-hydroxymetoprolo to metoprolol

Figure 2.

Mean metoprolol (M) and α-hydroxymetoprolol (HM) plasma concentration–time profiles on day 1 (control) and day 8 (treatment with imatinib) for intermediate metabolizers (IMs, n = 6) and extensive metabolizers (EMs, n = 13)

In the presence of 400 mg twice daily imatinib, the plasma Cmax and AUC values of metoprolol increased in all patients (Table 3). The 90% CI of the geometric mean ratios of Cmax and AUC(0,∝) of metoprolol was not completely contained in the interval (0.8, 1.25), suggesting a small, albeit statistically significant interaction between imatinib and metoprolol. In IMs, the mean Cmax increased by ∼15%, and the mean AUC values increased by 17%. In EMs, the mean Cmax increased by 21% and the mean AUC values increased by 24%. The overall AUC increase for metoprolol was approximately 23%. Both the clearance and volume of distribution of metoprolol (CL/F and V/F) were reduced following co-administration with imatinib than metoprolol alone.

In the presence of imatinib, the geometric mean Cmax value of α-hydroxymetoprolol decreased by 8%, but did not achieve a significant difference level. The 90% CI of the geometric mean ratio of Cmax (0.87, 0.98) is contained in the interval (0.8, 1.25). On the other hand, the AUC value of α-hydroxymetoprolol increased significantly (by 34%) in the presence of imatinib, with the 90% CI (1.27, 1.41) not being contained in the interval (0.8, 1.25). The metabolic ratio, calculated as the AUC(0,∝) ratio of α-hydroxymetoprolol to metoprolol, was not different between with and without co-administration of imatinib, 0.972 and 0.893, respectively. Between IM and EM phenotypes, the metabolite to parent drug AUC ratio was significantly different (P = 0.01), with a mean value of 0.53 ± 0.37 for IMs (n = 6) and 1.32 ± 0.62 for EMs (n = 13).

Imatinib 400 mg twice daily was well tolerated during the 8 day study period. One case of grade 2 pyrexia was reported on study day 6 in one patient. This adverse event lasted approximately 7 h and did not result in discontinuation or alteration of the study medication. There were no clinically significant changes in laboratory parameters, vital signs or ECG examinations.

Discussion

Early studies have documented that that CYP2D6 *1 and *2 are normal functional alleles, *5 is a nonfunctional allele, and *10 *36 and *41 are alleles with reduced activities [14, 15, 18, 25, 26]. The frequency of major CYP2D6 alleles identified in the present study, 28.9% for CYP2D6 *1, 7.9% for *2, and 52.6% for *10, was similar to those reported previously for the Chinese population [18–20], although the sample size was small for the present study. CYP2D6 *10, an allele coding for less active enzyme or low enzyme expression, seems to be the most common allele, ∼50%, in the Chinese population, but it is rare in Caucasians [18]. The presence of this common and yet low enzyme activity allele seems to be one of the major reasons for a different CYP2D6 phenotype distribution between Chinese and Caucasians. The CYP2D6 EMs to IMs ratio for the Chinese population in the present study was 65% to 30%, as compared with 75% to 17% for Caucasians [16, 17]. The PK parameters for metoprolol showed no major differences between Chinese or Caucasian populations. For CYP2D6 EMs, the most common 2D6 phenotype for both populations, the clearance and half-life of metoprolol were 175 l h−1 and 3.6 h, respectively, in the present study (Chinese population), and were 168 l h−1 and 5 h, respectively, in Caucasians in one study [27] and 111 l h−1 and 2.9 h, respectively, in another reported in the literature [28]. The PK parameters for CYP2D6 IMs and PMs are often combined for Caucasians due to a low frequency for both phenotypes.

When co-administered with imatinib, the average plasma exposure to metoprolol was increased by approximately 23%, but the extent of increase appeared to be slightly different between different 2D6 phenotypes. The average plasma AUC of metoprolol was increased by 17% in IMs, 24% in EMs, and 28% for the subject with unknown 2D6 status. Although a greater increase in exposure was observed in EM patients, the elevated exposure of metoprolol in these patients was still lower than those in IM patients in the absence of imatinib on day 1 or in the presence of imatinib on day 8.

The formation of α-hydroxymetoprolol appeared to be inhibited by imatinib as shown by a somewhat decreased Cmax value (approximately 8%), although not achieving a statistically significant difference level. The tmax value was also prolonged slightly from a mean 3.2 h to 5 h in IM and from 2.4 h to 3.4 h in EM patients. Interestingly, the plasma AUC exposure of hydroxymetoprolol showed an increase in all patients, approximately 34% in all 20 patients combined, or ∼41%, 30%, and 52% for IM, EM, and the subject with unknown 2D6 status, respectively. The exact mechanism for the increase in hydroxymetoprolol AUC is still unclear. If only the formation of α-hydroxymetoprolol, which is mediated by CYP2D6, is inhibited by imatinib, the plasma AUC of α-hydroxymetoprolol should be decreased as for the Cmax value, not increased. Thus, these results might suggest that the elimination of the hydroxy metabolite was probably decreased in the presence of imatinib, and the extent of the decrease in the elimination (or secondary metabolism) of the metabolite was probably more profound than the decreased formation rate, resulting in a net increase in plasma exposure.

The plasma Cmax and AUC values of imatinib observed in Chinese patients with CML from the present study, 4245 ng ml−1 and 39 041 ng ml−1 h, respectively, appeared to be slightly (approximately 15%) higher than those in Caucasian patients with CML reported at the same dose (800 mg daily) from the phase I study [4], 3702 (± 1434) ng ml−1 and 34 200 (± 14 900) ng ml−1 h, respectively. The effective half-life estimated based on the accumulation factor from the present study was approximately 25 h, somewhat longer than that in Caucasians, approximately 20 h [4]. Comparing the clearance values, which could be estimated from different doses since imatinib demonstrated a linear dose-exposure relationship, the results showed no major differences between the two patient populations (<25%), though the clearance in Chinese patients with CML (11.3 l h−1) appeared to be in the lower end of the values reported for Caucasian patients with CML, between 10 and 14 l h−1[4, 29, 30].

The recommended starting dose of imatinib for both CML and GIST is 400 mg day−1, with escalation to 600 and 800 mg day−1 if the patient does not respond to the starting dose. To maximize the potential interaction between imatinib and metoprolol, the high dose of imatinib 800 mg day−1 was selected. At 800 mg daily dose, the peak plasma concentration of imatinib observed in the present study, 4245 ng ml−1 (∼8.6 μm), was of the same order of magnitude as the in vitro Ki value of 7.5 μm for CYP2D6 inhibition without considering the protein binding in vitro and in vivo. Under these experimental conditions, the percentage increase in metoprolol plasma AUC was considered to be small or moderate, 23% overall, and 17% for IMs and 24% for EMs. These values seem to be in line with what would be predicted based on the in vitro Ki value, imatinib peak plasma concentration [I], and the fraction of metoprolol metabolized by CYP2D6 (fm) according to the following equation [31]:

|

(2) |

With a fm value of 0.85 for metoprolol, a peak plasma concentration [I] of 8.6 μm for imatinib and a Ki value of 7.5 μm, the predicted AUCi : AUC ratio will be 1.8-fold assuming the same protein binding in plasma (95% bound) and in microsomal incubate. Since there are less proteins in the in vitro incubate than in plasma, the free fraction of imatinib in incubate would be higher than that in plasma. Thus, for a given free fraction in the incubate of 10%, 20%, and 30% while maintaining the same free fraction in plasma (5%), the AUCi : AUC ratio would be 1.45-, 1.23-, and 1.16-fold, respectively. These predicted values are comparable with the average value, 23% estimated in the present study.

In conclusion, co-administration of a high dose imatinib resulted in a moderate increase in metoprolol plasma exposure for both the peak or AUC values. Although the increase appeared to be greater in patients who were extensive 2D6 metabolizers, the elevated concentration in these patients was still lower than those in intermediate metabolizers under control conditions (without imatinib). Thus, CYP2D6 status does not appear to be a risk factor for metoprolol or other CYP2D6 substrates when co-administered with imatinib. The clearance of imatinib in Chinese patients with CML showed no difference between CYP2D6 IMs and EMs and no major difference from Caucasian patients with CML based on data reported in the literature.

Acknowledgments

The financial support for this study was from Novartis.

REFERENCES

- 1.O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, Cornelissen JJ, Fischer T, Hochhaus A, Hughes T, Lechner K, Nielsen JL, Rousselot P, Reiffers J, Saglio G, Shepherd J, Simonsson B, Gratwohl A, Goldman JM, Kantarjian H, Taylor K, Verhoef G, Bolton AE, Capdeville R, Druker BJ. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanke CD, Corless CL. State-of-the art therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:274–80. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200055972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng B, Lloyd P, Schran H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of imatinib. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:879–94. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng B, Hayes M, Resta D, Racine-Poon A, Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Sawyers CL, Rosamilia M, Ford J, Lloyd P, Capdeville R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imatinib in a Phase I trial with chronic myeloid leukemia patients. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:935–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dutreix C, Peng B, Mehring G, Hayes M, Capdeville R, Pokorny R, Seiberling M. Pharmacokinetic interaction between ketoconazole and imatinib (Glivec) in healthy subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;54:290–4. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0832-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton AE, Peng B, Hubert M, Krebs-Brown A, Capdeville R, Keller U, Seiberling M. Effect of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, STI571) in healthy subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:102–6. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith PF, Bullock JM, Booker BM, Haas CE, Berenson CS, Jusko WJ, Influence of St. John's wort on the pharmacokinetics and protein binding of imatinib mesylate. Pharmacother. 2004;24:1508–14. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.16.1508.50958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frye RF, Fitzgerald SM, Lagattuta TF, Hruska MW, Egorin MJ, Effect of St. John's wort on imatinib mesylate pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reardon DA, Egorin MJ, Quinn JA, Rich JN, Gururangan S, Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Sathornsumetee S, Provenzale JM, Herndon JE, Dowell JM, Badruddoja MA, McLendon RE, Lagattuta TF, Kicielinski KP, Dresemann G, Sampson JH, Friedman AH, Salvado AJ, Friedman HS. Phase II study of imatinib mesylate plus hydroxyurea in adults with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9359–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Brien SG, Meinhardt P, Bond E, Beck J, Peng B, Dutreix C, Mehring G, Milosavljev S, Huber C, Capdeville R, Fischer T. Effects of imatinib mesylate (STI571, Glivec) on the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin, a cytochrome P450 3A4 substrate, in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1855–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGourty JC, Silas JH, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Woods HF. Metoprolol metabolism and debrisoquine oxidation polymorphism – population and family studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;20:555–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb05112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Woods HF. The polymorphic oxidation of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists. Clinical pharmacokinetic considerations. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1986;11:1–17. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198611010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker GT, Houston B, Huang SM. Optimizing drug development: strategies to assess drug metabolism/ transporter interaction potential – toward a consensus. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:103–14. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.116891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanger UM, Fischer J, Raimundo S, Stuven T, Evert BO, Schwab M, Eichelbaum M. Comprehensive analysis of the genetic factors determining expression and function of hepatic CYP2D6. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:573–85. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanger UM, Raimundo S, Eichelbaum M. Cytochrome P450 2D6: overview and update on pharmacology, genetics, biochemistry. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:23–37. doi: 10.1007/s00210-003-0832-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sachse C, Brockmoller J, Bauer S, Roots I. Cytochrome P450 2D6 variants in a Caucasian population: allele frequency and phenotypic consequences. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:284–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fux R, Morike K, Prohmer AMT, Delabar U, Schwab M, Schaeffeler E, Lorenz G, Gleiter CH, Eichelbaum M, Kivisto KT. Impact of CYP2D6 genotype on adverse effects during treatment with metoprolol: a prospective clinical study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:378–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradford LD. CYP2D6 allele frequency in European Caucasians, Asians, Africans and their descendants. Pharmacogenomics. 2002;3:229–43. doi: 10.1517/14622416.3.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ling JI, Pan S, Wu J, Marti-Jaun J, Hersberger M. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2D6 in Chinese mainland. Chinese Med J. 2002;115:1780–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang JD, Chuang SK, Cheng CL, Lai ML. Pharmacokinetics of metoprolol enantiomers in Chinese subjects of major CUpsilonP2D6 genotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;65:402–7. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(99)70134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AmpliChip CYP450 Test for in vitro diagnostic test. [3 April 2007]; Package insert. Available at http://www.amplichip.us/documents/CYP450_P.I. US IVD Sept. 15, 2006.pdf.

- 22.Home Page of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Committee. [3 April 2007]; Available at http://www.cypalleles.ki.se/

- 23.Bakhtiar R, Lohne J, Ramos L, Khemani L, Hayes M, Tse F. High throughput quantification of the anti-leukaemia drug STI571 (Gleevec) and its main metabolite (CGP 74588) in human plasma using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;768:325–40. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hout MWJ, Wilkens G, Van der Staal-Braaksma KA. Validation of a method for the determination of metoprolol and a-hydroxymetoprolol in human plasma samples. 2005. Pharma Bio-Research Group BV, The Netherlands, Internal Assay Method Report.

- 25.Raimundo S, Fischer J, Eichelbaum M, Griese EU, Schwab M, Zanger UM. Elucidation of the genetic basis of the common ‘intermediate metabolizer’ phenotype for drug oxidation by CYP2D6. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:577–81. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson I, Oscarson M, Yue QY, Bertilsson L, Sjöqvist F, Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic analysis of the Chinese cytochrome P4502D locus: characterization of variant CYP2D6 genes present in subjects with diminished capacity for debrisoquine hydroxylation. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:452–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchheiner J, Heesch C, Bauer S, Meisel C, Seringer A, Goldammer M, Tzvetkov M, Meineke I, Roots I, Bröckmoller J. Impact of the ultrarapid metabolizer genotype of cytochrome P450 2D6 on metoprolol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:302–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma S, Pibarot P, Pilote S, Dumesnil JG, Arsenault M, Belanger PM, Meibohm B, Hamelin BA. Modulation of metoprolol pharmacokinetics and hemodynamics by diphenhydramine coadministration during exercise testing in healthy premenopausal women. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:1172–81. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.081109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidli H, Peng B, Riviere GJ, Capdeville R, Hensley M, Gathmann I, Bolton AE, Racine-Poon A IRIS Study Group. Population pharmacokinetics of imatinib mesylate in patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukaemia: results of a phase III study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widmer N, Decosterd LA, Csajka C, Leyvraz S, Duchosal MA, Rosselet A, Rochat B, Eap CB, Henry H, Biollaz J, Buclin T. Population pharmacokinetics of imatinib and the role of alpha-acid glycoprotein. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:97–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland M, Matin SB. Kinetics of drug–drug interactions. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1973;1:553–67. [Google Scholar]