Abstract

AIMS

The oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug capecitabine is widely used in oncology. Capecitabine was designed to generate 5FU via the thymidine phosphorylase (TP) enzyme, preferentially expressed in tumoral tissues. Hand–foot syndrome (HFS) is a limiting toxicity of capecitabine. A pilot study on healthy volunteers was conducted in order to test the hypothesis that the occurrence of HFS could be related to tissue-specific expression of drug-metabolizing enzymes in the skin of the palm and sole. To this end, the expression of TP (activating pathway), dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD, catabolic pathway) and cell proliferation (Ki67) were measured in the skin of the palm (target tissue for HFS) and of the lower back (control area).

METHODS

Two paired 4-mm diameter punch biopsy specimens (palm and back) were taken in 12 healthy volunteers. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed on frozen tissues.

RESULTS

Proliferation rate (Ki67 staining) was significantly higher in epidermal basal cells of the palm compared with the back (P = 0.008). Also, TP and DPD expression were significantly greater in the palm relative to the back (P = 0.039 and 0.012, respectively). TP and Ki67 expression were positively and significantly correlated in the palm.

CONCLUSIONS

The high proliferation rate of epidermal basal cells in the palm could make them more sensitive to the local action of cytotoxic drugs. TP-facilitated local production of 5FU in the palm during capecitabine treatment could explain the occurrence of HFS. This observation may support future strategies to limit the occurrence of HFS during capecitabine therapy.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Hand–foot syndrome (HFS) is a limiting toxicity of the widely used fluorouracil (5FU) prodrug capecitabine.

The pharmacological origin of HFS has not been elucidated.

The expression of capecitabine-metabolizing enzymes thymidine phosphorylase (TP, activating pathway) and dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD, catabolic pathway) in the skin of the palm (target tissue for HFS) is unknown.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This pilot study, conducted in healthy volunteers, clearly demonstrated that TP expression is significantly greater in the palm compared with the lower back (control area).

This suggests TP-facilitated enhanced production of 5FU in the palm that could explain the occurrence of HFS.

This result may support strategies to prevent HFS.

Keywords: capecitabine, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, hand–foot syndrome, Ki67, skin, thymidine phosphorylase

Introduction

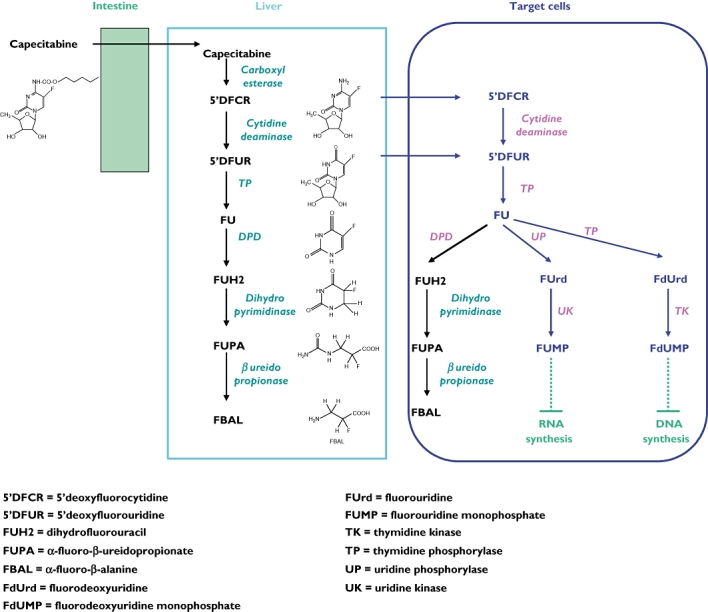

Capecitabine (Xeloda®; F. Hoffmann La-Roche, Basel, Switzerland) is a widely used oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug that is both effective and well-tolerated in the treatment of a number of cancers, including breast cancer and gastrointestinal (GI) cancers such as colorectal, gastric, pancreatic cancer and others [1]. Capecitabine (N4-pentyloxycarbonyl-5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine) was designed to generate fluorouracil (5FU) preferentially in tumour tissue compared with healthy tissue [2]. Capecitabine is metabolized to 5FU via a three-step enzymatic process (Figure 1). In the first step, capecitabine is hydrolysed by carboxylesterase in the liver to the intermediate 5′-DFCR. In the second step, 5′-DFCR is converted to 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine (5′-DFUR) by cytidine deaminase, which is highly active in the liver and tumour tissue. In the third step, 5′-DFUR is converted to 5FU by thymidine phosphorylase (TP), which is present in tumour tissue, resulting in the release of 5FU preferentially in tumour tissue. In addition, TP is also involved in the activation of 5FU into fluorodeoxyuridine that will further inhibit the DNA synthesis pathway (Figure 1). TP occurs at levels 3–10 times higher in tumour cells than in healthy tissue [2]. This can enable selective drug activation of 5FU at the tumour site and limit systemic toxicity [3]. Finally, 5FU is catabolized into dihydrofluorouracil by the dihydropyrimidine deshydrogenase (DPD) enzyme that is present in almost all tissues.

Figure 1.

Capecitabine metabolic pathways

Capecitabine is generally well-tolerated and has an improved tolerability profile compared with bolus 5FU/LV [1, 4]. Its most common dose-limiting adverse events are diarrhoea, hyperbilirubinaemia and hand–foot syndrome (HFS), also called palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia. Other frequent adverse events include fatigue/weakness, abdominal pain and other GI effects such as nausea/vomiting and stomatitis/mucositis. Compared with bolus 5FU/LV, capecitabine is associated with more HFS but less stomatitis, alopecia, diarrhoea, nausea and neutropenia [4, 5]. Of note, HFS is a side-effect that occurs with continuous 5FU infusion, but which is almost absent with bolus 5FU [6]. HFS is also observed with other cytotoxic drugs such as liposomal doxorubicin, cytarabine and docetaxel [7, 8] or targeted therapies such as sorafenib [9]. The overall incidence of HFS observed with capecitabine in clinical trials of breast or colorectal cancer is around 50%, with 17% of patients reporting a severe form (grade 3) [1].

The symptoms of HFS have been well-studied and include numbness, dysaesthesia/paraesthesia, tingling, erythema, painless swelling or discomfort and, in more severe cases, blisters, ulceration, desquamation or severe pain on the palms of the hands and/or the soles of the feet [10–12]. The majority of patients present with dysaesthesia, usually a tingling sensation of the palms and soles, which may progress to burning pain with swelling and erythema in 3–4 days. The hands are usually more affected than the feet and can be the only area affected. More severe HFS can be uncomfortable and can interfere with patients' everyday activities. Moreover, it can necessitate a reduction in the dose of the chemotherapeutic agent or treatment interruption or withdrawal. Nevertheless, treatment interruption followed by dose reduction, if necessary, usually leads to rapid reversal of signs and symptoms without long-term consequences [5]. HFS is never life-threatening.

Tissues affected by HFS exhibit inflammatory changes such as dilated blood vessels, oedema and white blood cell infiltration [7, 10]. However, the causative mechanisms of HFS are still unknown. Local delivery of high drug concentrations though eccrine glands has been advocated in the aetiology of HFS induced by doxorubicin [13] or sorafenib [9]. HFS may also be favoured by the increased vascularization, temperature and pressure in the hands and feet. For 5FU, HFS is dose-dependent and is possibly related to the accumulation of 5FU or its metabolites in the skin [14, 15]. In contrast, for capecitabine, no correlation has been reported between plasma concentrations of capecitabine metabolites and the occurrence of HFS [4, 16, 17]. This lack of correlation for capecitabine is not surprising, since 5FU is generated intracellularly by thymidine phosphorylase. The fact that 5FU prodrugs containing DPD inhibitors, such as uracil/tegafur (UFT), do not frequently induce HFS [18] is intriguing and suggests a role of 5FU catabolites in the occurrence of HFS, particularly in case of high DPD activity in HFS target tissue. The presence of TP has been reported in human epidermal keratinocytes [19, 20]. Thus, another possible mechanism for capecitabine-related HFS could be that keratinocytes in the skin of the palm and sole may contain increased levels of TP, which leads to the production and accumulation of 5FU through local capecitabine metabolic activation. The aim of this study, specifically focused on the understanding of capecitabine-related HFS, was thus to test the above hypotheses. To this end, we compared TP and DPD expression between the palm area (target zone) and a control area (skin of the back) in 12 healthy volunteers. In addition, the expression of Ki67, which is a marker of cell proliferation, was examined. As quantification method, we adopted immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, since it allows the expression of the studied parameters to be examined within the different areas of a complex tissue such as the epidermis, along with the distribution among and within the cells (i.e. cytoplasm vs. nucleus).

Methods

Subjects

This study was conducted in 12 healthy volunteers (seven men, five women, mean age 37.5 years, range 27–54 years). All volunteers provided written, informed consent and the study received the approval of the local ethics committee.

Skin biopsies

Two paired skin biopsy specimens (punch biopsies) of 4 mm diameter were taken from each subject by a dermatologist. One was taken from the palm of the hand (thumb base or lateral palmar area) and the other from the lower back, which served as the control area. Before sampling, the skin around the biopsy site was cleaned and a local anaesthetic (1% lidocaine) administered. A small cylinder of skin was then removed using a punch biopsy taken perpendicular to the skin. The skin biopsy specimens were placed in a cryotube, labelled, and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Immunohistochemical analyses

IHC analyses were performed on frozen tissue sections. Skin biopsy specimens were sectioned using a freezing microtome (cryotome), which produced 3–5-μm samples from the punch biopsies. Sections spontaneously adhered to glass slides by unfixed proteins and were air-dried. IHC was performed using the classical indirect method: unlabelled mono-specific primary antibody incubation followed by a second incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (antimouse IgG). The peroxidase reaction was developed using the 3-amino 9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) kit from Dako as chromogen, and sections were counterstained with haematoxylin. Omission of the primary antibody was used as a negative control.

| Manufacturer | Type of antibody | Dilution | Incubation length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | Calbiochem | Monoclonal | 1 : 100 | 30 min |

| DPD | Roche | Monoclonal | 1 : 100 | 30 min |

| Ki67 | Dako | Monoclonal | 1 : 50 | 30 min |

After staining, slides were evaluated by two pathologists (S.L. and P.H.) in a blinded fashion, using a light microscope. Discrepancies were resolved by the two pathologists using a multihead microscope. All IHC evaluations were performed blind with respect to the clinical information. Each observer counted 10 fields per sample (×1000 magnification microscopic fields). Immunoreactivity was classified by estimating the percentage of epithelial cells showing immunopositivity (from 0% to 100%) and by estimating the intensity of reactivity (absent, moderate, strong reactivity). Briefly, Ki67 and TP scoring were performed by determining the percentage of positive nuclei from regions of maximal nuclear reactivity after counting 1000 epithelial cells. Similarly, DPD scoring was performed by determining the percentage of positive cytoplasmic cells from regions of maximal cytoplasmic reactivity after counting 1000 epithelial cells. The IHC score was assigned according to both the percentage of positive cells and the intensity of reactivity, as follows:

| % of positive cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <10% | 10–25% | >25% | |

| No staining | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate staining | + | + | ++ |

| Strong staining | + | ++ | +++ |

Statistics

Since literature data did not provide data on interpatient variability in TP and DPD expression in skin, the present study was a pilot study aimed at testing a hypothesis on a limited set of 12 healthy volunteers. Paired-comparison of IHC scores was performed according to the nonparametric sign test, using an exact test method so as to estimate the exact two-sided P-value. Correlations between IHC scores were tested by means of the nonparametric Spearman test. Statistics were drawn up on SPSS Inc. software, version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

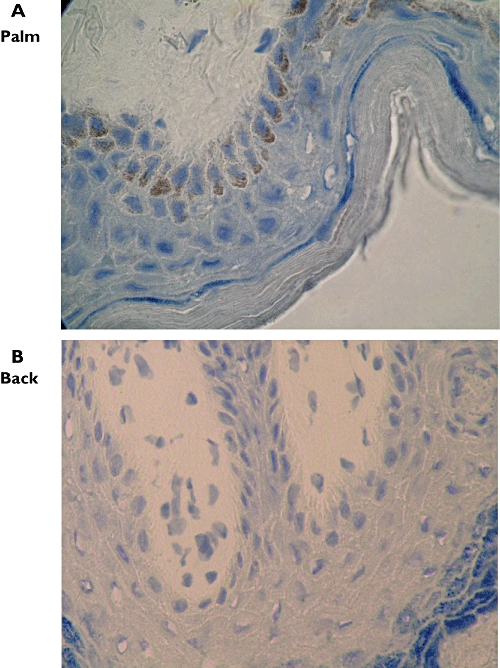

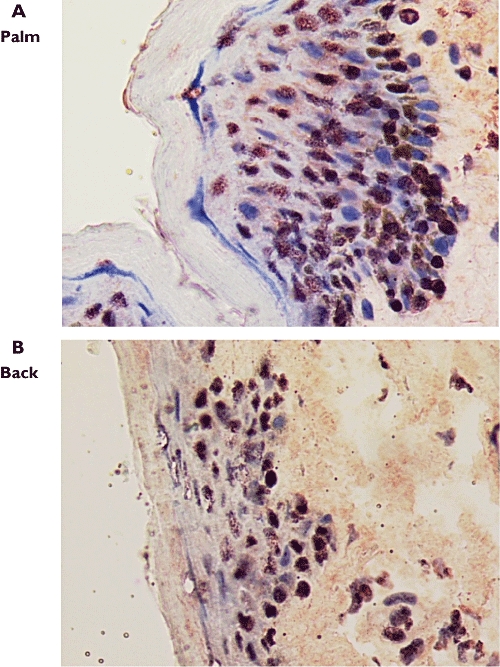

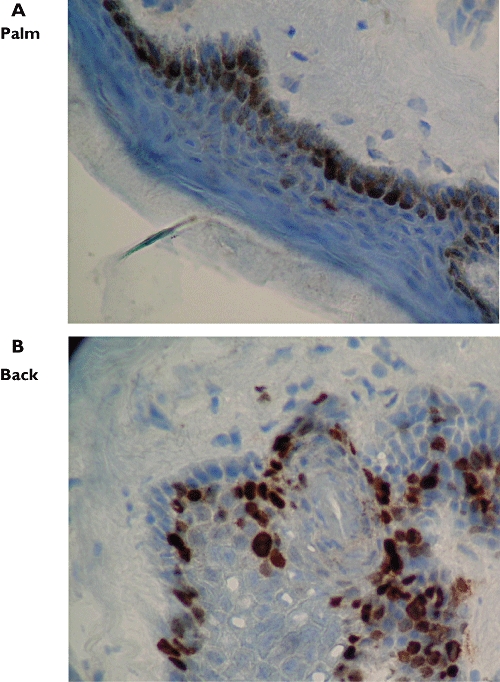

Localization of reactivity of TP and Ki67 was limited to the nuclei, whereas reactivity of DPD was exclusively localized in the cytoplasm. DPD and Ki67 reactivity were located predominantly in the basal layer of the epidermis, whereas TP reactivity was distributed across the basal and suprabasal areas of the epidermis, with generally higher intensity in the basal layer (Figures 2–4). In all subjects, immunopositivity (+ to +++) for TP and Ki67 was observed in both the palm area and the back area (Table 1). For DPD, 11 out of the 12 volunteers had immunopositivity in the palm as well as in the back area (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) immunoreactivity in skin biopsy specimens from the palm (A, ×1000) and back (B, ×1000), subject 3

Figure 4.

Thymidine phosphorylase (TP) immunoreactivity in skin biopsy specimens from the palm (A, ×1000) and back (B, ×1000), subject 3

Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry results

| TP | DPD | Ki67 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Age | Sex | Palm | Back | Palm | Back | Palm | Back |

| 1 | 54 | F | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | + |

| 2 | 53 | M | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + |

| 3 | 34 | M | +++ | + | 0 | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| 4 | 33 | F | +++ | ++ | ++ | NA | +++ | ++ |

| 5 | 39 | M | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| 6 | 37 | M | ++ | + | + | 0 | ++ | ++ |

| 7 | 28 | M | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| 8 | 27 | F | + | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| 9 | 40 | F | +++ | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | ++ |

| 10 | 30 | M | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| 11 | 44 | F | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| 12 | 31 | M | ++ | + | ++ | + | + | + |

| Statistics (sign paired test) | P = 0.039 | P = 0.012 | P = 0.008 | |||||

TP, thymidine phosphorylase; DPD, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase; NA, not assessable.

Figure 3.

Ki67 immunoreactivity in skin biopsy specimens from the palm (A, ×1000) and back (B, ×1000), subject 9

Intrapatient comparison between palm and back areas revealed that TP, DPD and Ki67 reactivity was significantly higher in the palm area compared with the back area (Table 1). The highest significance was observed for Ki67 (P = 0.008, eight cases with greater expression in the palm, four equal cases). For DPD, one case was not assessable (P = 0.012, 10 cases with greater expression in the palm and one opposite case). For TP, eight subjects expressed greater reactivity in the palm, one expressed the opposite and three equal cases were observed (P = 0.039).

Interestingly, TP and Ki67 expression were positively and significantly correlated in the palm (r = 0.658, P = 0.020), whereas no such relationship was observed in the back area (P = 0.93). In both palm and back areas, no relationship was observed between DPD and Ki67 expression, nor between DPD and TP expression. Paired-comparison between palm and back areas showed a slight correlation for Ki67 expression (r = 0.59, P = 0.044), but no correlation for TP or DPD.

Discussion

HFS is a common dose-limiting toxicity of capecitabine, which can occur in up to 53% of patients [1]. If not promptly managed, HFS can progress to an extremely painful and debilitating condition, causing significant discomfort and impairment of function, potentially leading to worsened quality of life in patients receiving capecitabine. However, treatment interruption and/or dose reduction usually leads to rapid reversal of the signs and symptoms of HFS. It is important to understand the pharmacological basis for HFS so as to provide a rationale for preventive or curative interventions. To this end, we analysed the expression (IHC) of the two main metabolic enzymes of capecitabine, namely TP (activating enzyme) and DPD (catabolic enzyme), along with the proliferation marker Ki67, in the HFS target tissue (palm area) and in a control area (lower back area) of 12 healthy volunteers.

The greatest significant difference observed in the present study was shown by the Ki67 analyses. Importantly, Ki67 was markedly overexpressed in the palm compared with the back (P = 0.008). The high proliferation rate of basal cells in the epidermis of the palm, as demonstrated by increased Ki67 expression, could make this skin area more sensitive to the action of cytotoxics in general, including the locally produced 5FU metabolites. This difference in cell kinetics between the skin of the palm and that of the back may result from differences in skin stem cells. Jones et al.[21] have shown that the distribution of stem cells in the skin is not random. In human epidermis, stem cells express high levels of α2β1 and α3β1 integrins whose labelling varies between sites and correlates with the distribution of S-phase cells [21]. Interestingly, a typical pattern of integrin staining was seen in the palms compared with other body sites [21]. Also, stem cells reside mainly in hair follicles [22] and, unlike the back area, palms and soles are devoid of hair follicles. Other features characterize palms and soles, such as the absence of melanocytes.

A major determinant of 5FU-related toxicity is DPD, the rate-limiting enzyme of 5FU catabolism being responsible for 80–90% of the drug's clearance [23]. Present data showed that DPD expression was significantly higher in the palm compared with the back area. Theoretically, an increased DPD level should enhance the production of 5FU catabolites, dihydrofluorouracil (FUH2) and α-fluoro-β-alanine (FBAL), for which cytotoxicity is not clearly established. A recent experimental study from our group on human keratinocytes has shown that FUH2 and FBAL did not enhance the cytotoxicity of 5′DFUR [16]. In contrast, on Ehrlich ascites tumour cells, Diasio et al. have reported cytotoxic activity of FUH2, with LD50 being 2.7-fold that of 5FU, whereas FBAL did not exhibit a major cytotoxic effect [24]. Also, neurotoxicity of FBAL was reported by Akiba et al. on murine cerebellar myelinated fibres [25]. Interestingly the clinical observation that HFS is almost absent with oral 5FU prodrugs containing DPD inhibitors, such as UFT or S-1, as recently discussed by Yen-Revollo and colleagues [6], supports a possible role of 5FU catabolites in the aetiology of HFS. The presence of a DPD inhibitor favours elevated 5FU concentrations in biological fluids, associated with elevated 5FU anabolite and low 5FU catabolite concentrations. In contrast, a 5FU prodrug not containing DPD inhibitor, such as capecitabine, favours the production of 5FU catabolites, as corroborated by the high proportions of FUH2 and FBAL, relative to 5FU and 5′DFUR, measured in patients receiving capecitabine [26]. Thus, the high DPD expression presently observed in the palm area should enhance the local production of 5FU catabolites that may increase cell cytotoxicity on this target tissue, although their cytotoxic effects are not clearly established.

Another major determinant of capecitabine activity is the TP enzyme responsible for capecitabine activation. Above all, the present study has shown that TP is markedly expressed in the skin, with significantly higher reactivity in the palm compared with the back area (only one subject out of the 12 showed the opposite pattern). This result strongly suggests that elevated TP expression in the HFS target tissue may favour cell cytotoxicity through elevated local production of 5FU during capecitabine treatment. This cell cytotoxicity is possibly emphasized by the elevated proliferation rate observed in the palm area that may render it more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of the locally produced 5FU. Moreover, since TP is also an angiogenic marker [27], this locoregional toxicity may also be linked to higher blood flow in the palm. In all, the present data provide strong arguments towards explaining the causative mechanisms of HFS specifically induced by capecitabine.

Additional results were provided by the present study, such as the positive correlation observed between Ki67 and TP expression in the palm area. This result corroborates correlations between TP expression and cell proliferation markers reported by other investigators in various other tissues [28, 29]. Also, intrasubject analysis revealed a positive correlation for Ki67 expression between palm and back areas. This latter observation may result from a germinal polymorphism of genes involved in cell proliferation, such as, for example, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. However, the EGFR gene is subject to several polymorphisms that control EGFR expression [30].

In summary, the present data suggest that the presence of elevated TP expression in the palms of the hands along with an increased basal cell proliferation rate could be a major causative mechanism for capecitabine-related HFS. Although direct measurement of drug levels in skin samples may pose a challenge, it would be interesting, in the light of the present results, to analyse 5FU and catabolites in palm vs. back in patients treated with capecitabine. These observations may provide an explanation for the origin of capecitabine-related HFS and may stimulate similar future studies in treated patients and support strategies to limit the occurrence of HFS during capecitabine treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walko CM, Lindley C. Capecitabine: a review. Clin Ther. 2005;27:23–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, Sawada N, Ishikawa T, Mori K, Shimma N, Umeda I, Ishitsuka H. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Can. 1998;34:1274–81. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Cassidy J, Allman D, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Findlay M, Frings S, Jahn M, McKendrick J, Osterwalder B, Perez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schmiegel WH, Seitz JF, Thompson P, Vieitez JM, Weitzel C, Harper P. Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4097–106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4097. Xeloda Colorectal Cancer Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassidy J, Twelves C, Van Cutsem E, Hoff P, Bajetta E, Boyer M, Bugat R, Burger U, Garin A, Graeven U, McKendric J, Maroun J, Marshall J, Osterwalder B, Pérez-Manga G, Rosso R, Rougier P, Schilsky RL. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:566–75. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf089. Capecitabine Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Capecitabine Colorectal Cancer Study Group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gressett SM, Stanford BL, Hardwicke F. Management of hand–foot syndrome induced by capecitabine. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2006;12:131–41. doi: 10.1177/1078155206069242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yen-Revollo JL, Goldberg RM, McLeod HL. Can inhibiting dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase limit hand–foot syndrome caused by fluoropyrimidines? Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagore E, Insa A, Sanmartin O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia (‘hand–foot’) syndrome. Incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:225–34. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webster-Gandy JD, How C, Harrold K. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (PPE): a literature review with commentary on experience in a cancer centre. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007;11:238–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai SE, Kuzel T, Lacouture ME. Hand–foot and stump syndrome to sorafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abushullaih S, Saad ED, Munsell M, Hoff PM. Incidence and severity of hand–foot syndrome in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: a single-institution experience. Cancer Invest. 2002;20:3–10. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heo YS, Chang HM, Kim TW, Ryu MH, Ahn JH, Kim SB, Lee JS, Kim WK, Cho HK, Kang YK. Hand–foot syndrome in patients treated with capecitabine-containing combination chemotherapy. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:1166–72. doi: 10.1177/0091270004268321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lassere Y, Hoff P. Management of hand–foot syndrome in patients treated with capecitabine (Xeloda®) Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:S31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobi U, Waibler E, Schulze P, Sehouli J, Oskay-Ozcelik G, Schmook T, Sterry W, Lademann J. Release of doxorubicin in sweat: first step to induce the palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome? Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1210–1. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leo S, Tatulli C, Taveri R, Campanella GA, Carrieri G, Colucci G. Dermatological toxicity from chemotherapy containing 5-fluorouracil. J Chemother. 1994;6:423–6. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.1994.11741178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diasio RB. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase modulation in 5-FU pharmacology. Oncology. 1998;12:23–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischel JL, Formento P, Ciccolini J, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Milano G. Lack of contribution of dihydrofluorouracil and alpha-fluoro-beta-alanine to the cytotoxicity of 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine on human keratinocytes. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15:969–74. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gieschke R, Burger HU, Reigner B, Blesch KS, Steimer JL. Population pharmacokinetics and concentration effect relationships of capecitabine metabolites in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:252–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douillard JY, Hoff PM, Skillings JR, Eisenberg P, Davidson N, Harper P, Vincent MD, Lembersky BC, Thompson S, Maniero A, Benner SE. Multicenter phase III study of uracil/tegafur and oral leucovorin versus fluorouracil and leucovorin in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3605–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asgari MM, Haggerty JG, McNiff JM, Milstone LM, Schwartz PM. Expression and localization of thymidine phosphorylase/platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in skin and cutaneous tumors. J Cutaneous Pathol. 1999;26:287–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz PM, Milstone LM. Thymidine phosphorylase in human epidermal keratinocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:353–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90740-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones PH, Harper S, Watt FM. Stem cell patterning and fate in human epidermis. Cell. 1995;80:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:339–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milano G, Etienne MC, Pierrefite V, Barberi-Heyob M, Deporte-Fety R, Renee N. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency and fluorouracil-related toxicity. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:627–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diasio RB, Schuetz JD, Wallace HJ, Sommadossi JP. Dihydrofluorouracil, a fluorouracil catabolite with antitumor activity in murine and human cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45:4900–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akiba T, Okeda R, Tajima T. Metabolites of 5-fluorouracil, alpha-fluoro-beta-alanine and fluoroacetic acid, directly injure myelinated fibers in tissue culture. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1996;92:8–13. doi: 10.1007/s004010050482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reigner B, Blesch K, Weidekamm E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of capecitabine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:85–104. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters GJ, De Bruin M, Fukushima M, Van Triest B, Hoekman K, Pinedo HM, Ackland SP. Thymidine phosphorylase in angiogenesis and drug resistance. Homology with platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;486:291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konno S, Takebayashi Y, Aiba M, Akiyama S, Ogawa K. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of thymidine phosphorylase and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in gastric carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2001;166:103–11. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00432-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao L, Itoh S, Furuta I. Thymidine phosphorylase expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:584–90. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amador ML, Oppenheimer D, Perea S, Maitra A, Cusatis G, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Baker SD, Ashfaq R, Takimoto C, Forastiere A, Hidalgo M. An epidermal growth factor receptor intron 1 polymorphism mediates response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9139–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]