Abstract

We examine whether temporally defined associations play a role in item recognition. The role of these associations in recall tasks is well-known; we demonstrate an important role in item recognition as well. We find that subjects are significantly more likely to recognize a test item as having been previously experienced if the preceding test item was studied in a temporally proximal list position. Further analyses show that this associative effect is almost entirely due to the highest confidence recognition judgments.

In old-new recognition, a subject studies a series of items and is then shown a series of test probes. Subjects judge whether each probe is “old” (i.e., a repetition of an item that was presented on the studied list), or “new” (an item that had not appeared during the experiment). Widely studied for almost one hundred years (Strong, 1912), the old-new recognition task is believed to measure item-specific memory, devoid of inter-item associations (Murdock, 1974; Humphreys, 1978). This is distinct from recall tasks, which rely on strong temporal associations among items (Raskin & Cook, 1937). For example, in the free recall task, recall of a list item tends to be followed by recall of an item studied in a nearby list position, even though the instructions permit subjects to recall items in any order they wish (Kahana, 1996).

Many models of recognition and recall capture this distinction between item and associative information (Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984; Hintzman, 1988; Humphreys, Pike, Bain, & Tehan, 1989; Murdock, 1982; Shiffrin & Steyvers, 1997). In these models, item information reflects a weighted summed similarity between the probe item and the contents of memory. Associative information is typically stored independently by means of a conjunctive process that binds the information comprising the individual items. Associations in these models are not only formed between simultaneously processed items, but can span several items that co-occur in a working memory buffer (e.g., Kahana, 1996; Sirotin, Kimball, & Kahana, 2005).

Although many models assume a strict boundary between item and associative information driving recognition and recall respectively, it has long been recognized that recognition and recall are complex tasks that reflect the interaction of multiple memory systems, processes or operations (see Kahana, Rizzuto, & Schneider, 2005, for a review). In the case of recognition memory, a major line of research assumes that two distinct types of item-specific information drive recognition judgments: a fast acting familiarity process and a slower recollective process (Arndt & Reder, 2002; Atkinson & Juola, 1974; Mandler, 1980; Yonelinas, 2001). Familiarity in these models coarsely maps onto the summed similarity notion described above. Recollection is a recall-like process that involves the recovery of specific source information about the remembered item and is accompanied by a conscious experience of having seen or heard the target item (Tulving, 1985).

What exactly is the nature of the recollective process that underlies some recognition judgments? We consider here the possibility that recollective experience reflects, in part, the shared information between items studied in temporal proximity rather than simply the detailed features of an individual item’s occurrence. In recall tasks, such associative features may be seen in the strong tendency for recall of an item to evoke memories of its neighbors (Kahana, 1996). To the extent that recognition of an item as “old” involves a recall-like recollection process, one might observe temporally-defined retrieval effects in item recognition, despite the fact that the task does not explicitly test associative information. This could point to the existence of common associative mechanisms in both associative recall and item recognition. Thus, our main goal in this paper is to examine the effects of temporal co-occurrence on recognition performance.

Light and Schurr (1973) offered some evidence for the possible role of temporal associative mechanisms in an item recognition task. For one group of subjects, old test probes were presented in the same order as they were studied; for a second group, the order of the old test probes was randomized. Subjects in the same-order group performed better on the recognition test than subjects in the random-order group. In a related study, Ratcliff and McKoon (1978) had subjects make recognition judgments on nouns read as part of a story. They found that recognition memory for an old item was enhanced when the previous old-item-probe came from within the same linguistic unit (e.g., within vs. between proposition, within vs. between sentence). With these linguistically organized materials, Ratcliff and McKoon did not find an effect of within-proposition inter-word distance. Their effect, rather, was carried by the co-occurrence of items within a given proposition or sentence.

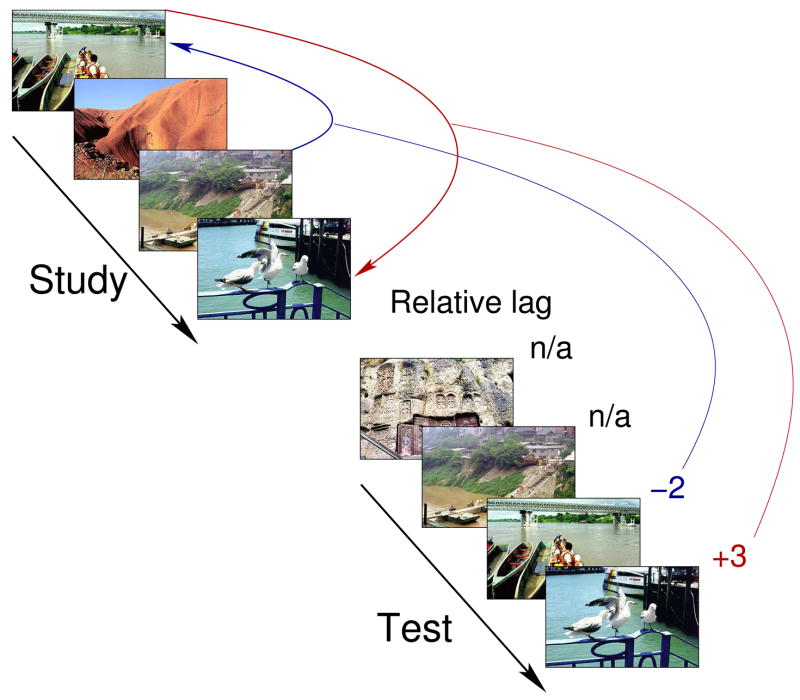

To assess the effect of temporal co-occurrence on recognition performance, we conducted an old-new recognition memory experiment using pictures as stimuli. The recognition test was a random sequence of test probes that included the old items from the list intermingled with an equal number of new items that served as lures. Subjects pressed one of six keys in response to each probe, rating their confidence that it was seen before from “1” (sure new) to “6” (sure old). The subjects’ ability to discriminate the old pictures from the new pictures must be a consequence of their memory for the studied items. A recognition test might include the sub-sequence of test probes (… O23, N, O12, O7, N, N, O39, …), where N denotes a new item and Ox denotes an old item from position x in the study list. When two successive test items are both old, as in (… Oi, Oj …), we define the lag between the items, r, as the distance, j − i, between the items on their initial presentation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relative lag and the item-recognition task.

After studying a series of pictures, subjects judged each picture in a test series as “old” (i.e., previously studied) or “new”. We define relative lag as the distance in the study list between successive old test items. Relative lag is only defined for successive old-item test probes.

Suppose that recognition of a test item, Oi, brings forth the mental state that prevailed when Oi was first encoded. Suppose further that this retrieved mental state contributes to the retrieval environment that determines subsequent recognition judgments. Then, if the very next test item is Oj, we would predict that memory for Oj should be enhanced when r = j − i is near zero.

Experiment

Methods

Subjects

Ninety-one Syracuse University undergraduates participated for course credit. The study was approved by the Syracuse University Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided informed consent.

Procedure

Each subject studied six lists of 64 digital pixmaps with 350 × 232 resolution. The images subtended ~5 deg. of visual angle. Images were obtained from planetware.com, a travel picture website, and presented on the screen for 1 s, with a 0.5 s blank interstimulus interval. A sequence of 128 test probes were given immediately following the study list. Half of the test probes were previously studied, old, items; the remainder were new.

A computer algorithm constructed the test lists separately for each subject. Old/new status was first randomly assigned to each test position. Old items were then assigned to test positions in two stages. First, randomly chosen pairs of old items with relative lags between −5 and +5 were placed in pairs of test positions that had been designated for old items. Second, the remaining test positions that were designated to have old items were filled with the remaining old items, and the test positions designated to have new items were filled with new pictures. This algorithm ensured that we would have sufficient data for each subject to assess the effect of relative lag within the range of −5 < r < +5.

In response to each test picture, subjects pressed a button from “1”–“6” to describe their confidence that the test item had been presented during study. Subjects were asked to give a response of “6” when they were absolutely certain that the test picture was previously studied (sure-old) and a response of “1” when they were absolutely certain that the test picture was not previously studied (sure-new). The keys were arranged to allow the subject to respond comfortably by using the first three fingers of each hand.

Responses longer than 3 sec. or shorter than 50 ms. were discarded. Subjects studied and were tested on a practice list prior to the first study list. Subjects were further instructed to use all six buttons and to respond as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. After the practice session, subjects were given feedback concerning their mean response time (RT) and the distribution of their responses across confidence levels.

Results

Subjects’ mean hit rate (HR; probability of correctly responding “4”, “5”, or “6” to an old item) was 0.68. Subjects’ mean false-alarm rate (FAR; probability of incorrectly responding “4”, “5”, or “6” to a new item) was 0.28. The mean value of d′ was 1.11. Mean RTs for hits, misses, false-alarms and correct-rejections were 1.05, 1.17, 1.24, and 1.17 sec. respectively. RTs for hits were significantly shorter than all other response types; RTs for false alarms were significantly longer (t(90) > 4.5, p < 0.001 for all comparisons). RTs for misses and correct rejections did not differ significantly (t = 0.60).

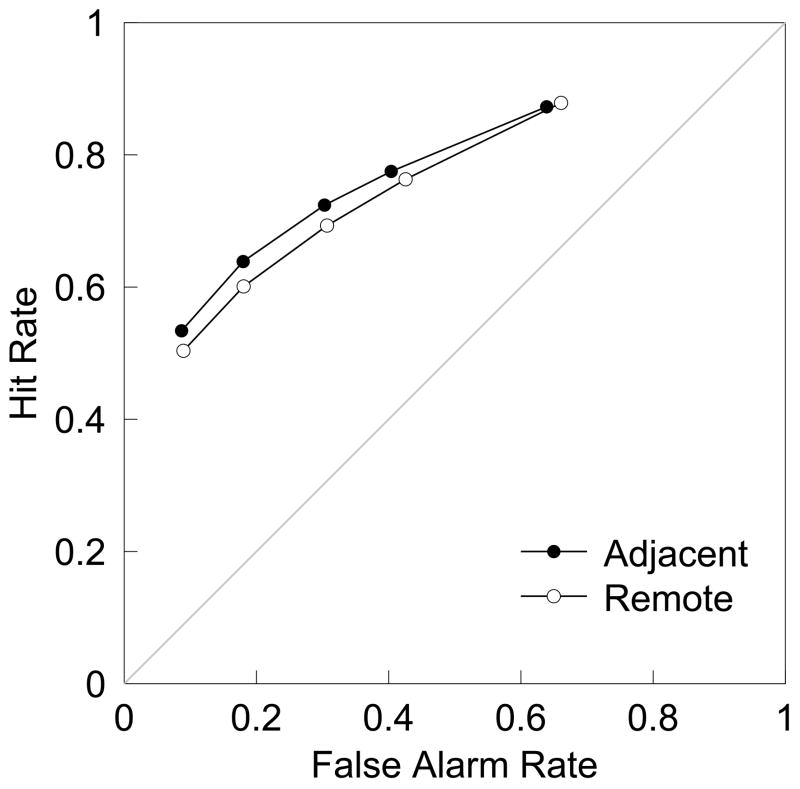

To assess the effect of temporal co-occurrence on recognition performance we compared responses to old items following items from adjacent list positions (|r| = 1) to those following items from remote positions (|r| > 10). Figure 2 shows receiver operating characteristic (ROC) functions for these two classes of old items. ROC functions describe HR as a function of FAR separately for each response criterion. That is, for each response criterion, we counted all responses greater than or equal to that criterion as an “old” response, and then calculated HR and FAR. To control for possible covariation of |r| and output position, we constructed a “local” FAR separately for each bin by taking new items that were preceded by a test item with a relative lag corresponding to the bin in question (Murdock & Kahana, 1993). As shown in Figure 2, HR was significantly higher for successive probes from adjacent list positions for the three most conservative criteria, [t(90) = 2.19, 3.00, 2.52, p < 0.05 paired-sample; Cohen’s d = 0.46, 0.63, and 0.53, respectively].

Figure 2. Temporal associative effects in old-new item recognition.

Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves characterize the hit-rate—false-alarm rate relation across levels of confidence.

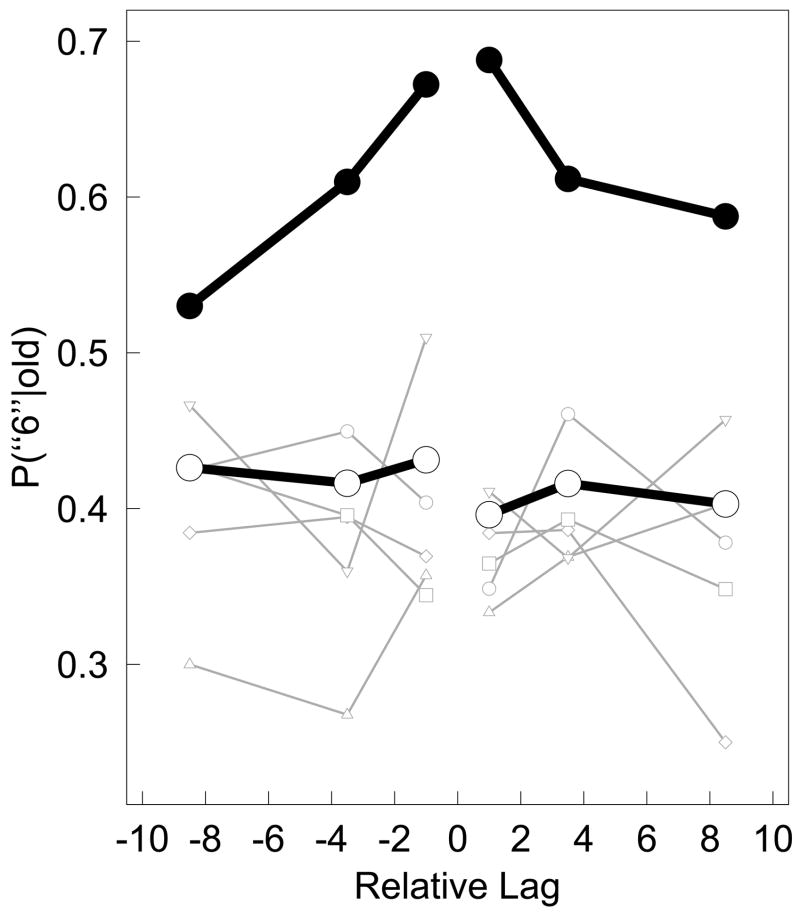

We further examined whether level of confidence mediated the recognition advantage for temporally-proximate items. Let (Oi,Oj ) denote a successively tested pair of old items appearing in positions i and j of the study list. We examined the joint effects of relative lag, r = j − i, and the confidence given to Oi on the probability of giving a sure-old response to Oj.

Figure 3 (filled circles) shows that sure-old responses to Oj following sure-old responses to Oi exhibited a strong associative effect, with highest-confidence HR being higher for small values of r. To better quantify this effect, we computed a linear regression of HR on |r| for each subject (we collapsed forward and backward values of r because the very small asymmetry apparent in the figure was not statistically reliable). The mean slope value obtained from this regression, −0.014 ± 0.004, was significantly different from zero (t(90) = 3.9, p < .001, d = 0.41). A total of 3791 data points entered into this analysis.

Figure 3. Temporal associative effects are specific to highest-confidence responses.

Probability of a highest confidence (“6”) response to an old-item test probe as a joint function the relative lag of, and the response given to, the preceding old-item probe. Large filled circles represent “6” responses to the prior test probe. Open symbols represent one of the other five possible prior responses; downward-facing triangles, boxes, triangles, upward-facing diamonds, and circles represent responses “1”–“5” respectively. Large open circles collapse data over responses “1”–“5”.

We next examined the effect of r on highest-confidence HR for items preceded by lower-confidence old responses. We found no effect of |r| on HR for probes preceded by responses 1–5 (range of t(90) .06 to 1.04, all p > .3). Noting that none of these responses showed a slope different from zero (or different from each other), we collapsed prior responses 1–5 into a single category (Figure 3, open circles). The mean slope collapsed across response categories 1–5 was not different from zero (0.000 ± 0.004). Our power to detect an effect of the same magnitude as that observed for the highest-confidence responses was 0.91 (two-tailed). A total of 3929 data points entered into this analysis of response categories 1–5. Importantly, the slope of the linear relation between |r| and HR was significantly less for these lower-confidence responses to Oi than when a highest-confidence response was given to Oi [t(90) = 2.67, p < .02, d = 0.56].

We next considered, and rejected, an encoding-based account of the associative effects shown in Figure 3. Suppose that during study the subject can be in either a good or a bad encoding state. Suppose further that these states have some “inertia” so that it takes some time to switch from one state to another. This latter assumption is plausible—examples of such long-range correlations have been reported in behavioral time-series data (Van Orden, Holden, & Turvey, 2003; Wagenmakers, Farrell, & Ratcliff, 2005). Under these two assumptions, items that receive a highest-confidence response during testing would likely have been encoded in the good-encoding state. Because this good state is hypothesized to persist for some time, items from nearby list positions would also be likely to have been learned in the good-encoding state. Correlated encoding states could therefore result in a pattern of results like that observed in Figure 3. As shown below, however, the implications of this correlated-encoding hypothesis and the temporal-retrieval hypothesis are readily distinguishable.

The correlated-encoding hypothesis predicts that contiguity effects should be observed even for pairs of items that were not tested successively. We tested this hypothesis by conducting the regression analysis described above on randomly chosen pairs of old-item test probes that were not tested successively. To ensure that our findings could not be due to a particular randomization, we repeated the analyses on 10,000 randomizations, each time evaluating the mean regression slope (across subjects) as in the original analysis. According to the correlated-encoding hypothesis, we should see the same effect of |r| on hit rate as shown in Figure 3. That is, an item studied in a proximate list position to an item recognized as sure-old should tend to be recognized as sure-old, even though the two items were not tested successively.

The mean regression slope for these non-successively-tested pairs, −.004, was significantly different from zero (the standard deviation across shuffles was 0.003, p < .001). We can therefore conclude that there is small, but significant, autocorrelation in the quality of encoding. However, this effect was not nearly large enough to account for the observed slope for successively tested pairs: −0.014 ± 0.004. Indeed, the slope for successively tested pairs was 2.9 standard deviations away from the slope of non-successively-tested pairs (p < .002). The effect observed in Figure 3 thus depends critically on test order and reflects a retrieval phenomenon.

General Discussion

The present results show that when two old items are successively tested, memory for the second is better if it was initially presented in temporal proximity to the first (Figure 2). This tendency, however, is wholly attributable to cases in which the first item receives a highest-confidence response (Figure 3). These highest-confidence responses may be considered to reflect successful recollection of the encoding episode (Sherman, Atri, Hasselmo, Stern, & Howard, 2003; Yonelinas, 1999). Our finding of temporal associative effects in item recognition suggests that recollection of an item not only retrieves detailed information about the item tested, but also retrieves information about the item’s neighbors.

On the basis of episodic recall data, temporal associations have been taken as evidence for rehearsal processes orchestrated by a working or short-term memory system. One might ask whether such rehearsal processes could explain the associative tendencies in item recognition demonstrated here. Although our pictures are not likely to be coded in a primarily verbal manner, it is nonetheless possible that verbal recoding was operative for at least a subset of our stimuli. As such, our findings may be a consequence of verbal rehearsal as characterized by the Search of Associative Memory (SAM) model of Shiffrin and colleagues (e.g., Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984) and by models of the phonological loop (e.g., Burgess & Hitch, 1999). Even if one could devise stimuli that would thoroughly resist verbal coding, an account based on visuo-spatial working memory could still potentially predict associative effects.

Theoretically, it would be appealing if the effects observed here in item recognition could be mapped on to similar associative tendencies that have been carefully documented in episodic recall tasks. In free recall, successively recalled items tend to have been studied in nearby list positions (Kahana, 1996). By analogy to the recency effect, which illustrates how items near-in-time to the end-of-list are better remembered, Howard and Kahana (1999) referred to associative effects in free recall as illustrating a lag-recency effect, as they reveal a preference for recalling items presented near-in-time to the just recalled item. Very similar lag-recency effects are observed in serial recall (Kahana & Caplan, 2002; Raskin & Cook, 1937; Klein, Addis, & Kahana, 2005). A difference between the results observed here, and the lag-recency effects observed in both free and serial recall, is that in both recall tasks subjects show a strong bias for making recall transitions in the forward direction. Insofar as our recognition data do not show any reliable asymmetry, this points to a potential difference between the associative processes underlying recognition and recall tasks.

It is worth considering these associative effects in light of several current models of episodic memory. SAM offers one possible framework in which to unify all of these associative effects. In SAM, associations are formed between nearby items during encoding by virtue of their co-ocurrence in short-term store. In episodic tasks, the just-recalled item serves as a cue for subsequent recalls, resulting in associative effects. In recognition testing, it is possible that associative effects across subsequent test items like those observed here could result if prior test items, stored in short-term memory, could contribute to a recognition decision for the current test.

Another possible approach to describing associative effects across paradigms would be to use a model based on retrieved temporal context. Context as an explanatory concept has long been used to describe changes in memory states over periods of time more extensive than a single list (Yntema & Trask, 1963; Anderson & Bower, 1972; Mensink & Raaijmakers, 1988). By assuming that when an item is recalled it retrieves its encoding context, Howard and Kahana (2002) were able to explain the lag-recency effect in free recall, and its approximate invariance across varying interitem delays. Because retrieved context overlaps with the encoding context of nearby items, associative effects can occur. This approach constitutes a departure from traditional accounts of association that assume direct item-to-item connections.

Retrieved temporal context has also been proposed as an explanation for a broad range of effects in item recognition. In their BCDMEM model, Dennis and Humphreys (2001) propose that a test probe retrieves contextual elements stored when the item was previously studied. For old test probes, this retrieved context will include elements from the study list as well as pre-experimental exposures to the word; for new test probes it will only include contextual elements from pre-experimental exposures. For each test probe, the retrieved contextual information is compared to a context vector representing the entire list. Dennis and Humphreys (2001) showed that BCDMEM accounts for a number of benchmark findings from item recognition, including the null list-strength effect (Ratcliff, Clark, & Shiffrin, 1990; but see Norman, 2002) the mirror effect (Glanzer & Adams, 1990), and data from Jacoby’s process dissociation procedure (Jacoby, 1992). Notably, BCDMEM predicted that context variability—the number of pre-experimental contexts in which a list item was experienced—should have an effect on recognition performance beyond the effect of word frequency. Consistent with this prediction, Steyvers and Malmberg (2003) showed that low context variability yielded better recognition performance.

A modified version of BCDMEM could reproduce the associative effects in item recognition reported here. First, the context retrieved by items would have to change gradually over time. This would be necessary to obtain the gradually-sloping contiguity effect observed here (Figure 3). Second, information recovered from one test probe would have to persist to contribute to the recognition decision on the subsequent probe. Third, some type of variability in contextual retrieval would have to be introduced to account for the distinction between recollection and familiarity that critically determines whether associative effects are observed (Figure 3). The first two of these modifications have already been proposed in developing a model of the lag-recency effect in free recall (Howard & Kahana, 2002; Howard, 2004) and would be relatively straightforward revisions to BCDMEM.

In summary, our view is that the information retrieved by a successful recollection includes the temporal context from the time the item was first presented (Dennis & Humphreys, 2001). Temporal context changes gradually over time (Howard & Kahana, 2002) and persists long enough after retrieval to contribute to the recognition decision on the next probe item. Taken together, the temporally-defined associations in recognition revealed here, and the ubiquitous observation of temporally-defined associations in recall (Howard & Kahana, 1999; Kahana, 1996; Kahana & Caplan, 2002; Raskin & Cook, 1937) suggest that recovery of temporal context is a fundamental process central to episodic memory. Furthermore, our finding that associative effects in recognition are limited to recollective responses adds to a growing body of neuroscientific evidence (reviewed by Rugg & Yonelinas, 2003) suggesting that recollection and familiarity are mediated by different brain mechanisms and/or structures.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NIMH grant MH55687 to the University of Pennsylvania and NIMH grant MH61492 to Syracuse University. We wish to thank Endel Tulving, Dan Schacter, Mike Humphreys, Ken Norman, and Andy Yonelinas for helpful discussions concerning this work. We also thank Madhura Phadke and Radha Modi for assistance with data collection and Jim Steinhart for photographic materials.

References

- Anderson JR, Bower GH. Recognition and retrieval processes in free recall. Psychological Review. 1972;79(2):97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt J, Reder LM. Word frequency and receiver operating characteristic curves in recognition memory: evidence for a dual-process interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28(5):830–42. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.5.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RC, Juola JF. Search and decision processes in recognition memory. In: Krantz DH, Atkinson RC, Suppes P, editors. Contemporary developments in mathematical psychology. San Francisco: Freeman; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N, Hitch GJ. Memory for serial order: A network model of the phonological loop and its timing. Psychological Review. 1999;106(3):551–581. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis S, Humphreys M. A context noise model of episodic word recognition. Psychological Review. 2001;108:452–478. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillund G, Shiffrin RM. A retrieval model for both recognition and recall. Psychological Review. 1984;91:1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanzer M, Adams JK. The mirror effect in recognition memory: data and theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16(1):5–16. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.16.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintzman DL. Judgments of frequency and recognition memory in multiple-trace memory model. Psychological Review. 1988;95:528–551. [Google Scholar]

- Howard MW. Scaling behavior in the Temporal Context Model. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2004;48:230–238. [Google Scholar]

- Howard MW, Kahana MJ. Contextual variability and serial position effects in free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25:923–941. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.4.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard MW, Kahana MJ. A distributed representation of temporal context. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2002;46:269–299. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys MS. Item and relational information: A case for context independent retrieval. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1978;17:175–187. [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys MS, Pike R, Bain JD, Tehan G. Global matching: A comparison of the SAM, Minerva II, Matrix, and TODAM models. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 1989;33:36–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LL. A process dissociation framework: Separating automatic from intentional uses of memory. Journal of Memory and Language. 1992;30:513–541. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ. Associative retrieval processes in free recall. Memory & Cognition. 1996;24:103–109. doi: 10.3758/bf03197276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ, Caplan JB. Associative asymmetry in probed recall of serial lists. Memory & Cognition. 2002;30:841–849. doi: 10.3758/bf03195770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana MJ, Rizzuto DS, Schneider A. An analysis of the recognition-recall relation in four distributed memory models. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2005 doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.31.5.933. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein KA, Addis KM, Kahana MJ. A comparative analysis of serial and free recall. Memory & Cognition. 2005 doi: 10.3758/bf03193078. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light LL, Schurr SC. Context effects in recognition memory: Item order and unitization. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1973;100:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler G. Recognizing: The judgment of previous occurrence. Psychological Review. 1980;87:252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Mensink GJM, Raaijmakers JGW. A model for interference and forgetting. Psychological Review. 1988;95:434–455. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB. Human memory: Theory and data. Potomac, MD: Erlbaum; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB. A theory for the storage and retrieval of item and associative information. Psychological Review. 1982;89:609–626. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock BB, Kahana MJ. List-strength and list-length effects: Reply to Shiffrin, Ratcliff, Murnane, and Nobel. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory and Cognition. 1993;19:1450–1453. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.19.6.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KA. Differential effects of list strength on recollection and familiarity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2002;28:1083–1094. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.28.6.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin E, Cook SW. The strength and direction of associations formed in the learning of nonsense syllables. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1937;20:381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Clark SE, Shiffrin RM. List-strength effect: I. Data and Discussion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1990;16:163–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, McKoon G. Priming in item recognition: Evidence for the propositional structure of sentences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1978;17(4):403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Rugg MD, Yonelinas AP. Human recognition memory: a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2003;7(7):313–319. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SJ, Atri A, Hasselmo ME, Stern CE, Howard MW. Scopolamine impairs human recognition memory: Data and modeling. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003;117:526–539. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffrin RM, Steyvers M. A model for recognition memory: REM—retrieving effectively from memory. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 1997;4:145. doi: 10.3758/BF03209391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotin YB, Kimball DR, Kahana MJ. Going beyond a single list: Modeling the effects of prior experience on episodic free recall. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005 doi: 10.3758/bf03196773. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyvers M, Malmberg KJ. The effect of normative context variability on recognition memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2003;29(5):760–6. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.29.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong JEK. The effect of length of series upon recognition memory. Psychological Review. 1912;19:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology. 1985;26:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden GC, Holden JG, Turvey MT. Self-organization of cognitive performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2003;132(3):331–50. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmakers EJ, Farrell S, Ratcliff R. Human cognition and a pile of sand: a discussion on serial cor relations and self-organized criticality. Journal of experimental psychology: General. 2005;134(1):108–16. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.1.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yntema DB, Trask FP. Recall as a search process. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior. 1963;2:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. The contribution of recollection and familiarity to recognition and source-memory judgments: a formal dual-process model and an analysis of receiver operating characteristics. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1999;25(6):1415–34. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.6.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonelinas AP. Components of episodic memory: the contribution of recollection and familiarity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Series B. 2001;356(1413):1363–1374. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]