Abstract

Mitogen-activated and extracellular regulated kinase (MEK) and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathways may underlie ethanol-induced neuroplasticity. Here, we used the MEK inhibitor UO126 to probe the role of MEK/ERK signaling for the cellular response to an acute ethanol challenge in rats with or without a history of ethanol dependence. Ethanol (1.5g/kg, i.p.) induced expression of the marker genes c-fos and egr-1 in brain regions associated both with rewarding and stressful ethanol actions. Under non-dependent conditions, alcohol-induced c-fos expression was generally not affected by MEK inhibition, with the exception of medial amygdala (MeA). In contrast, following a history of dependence, a markedly suppressed c-fos response to acute ethanol was found in medial prefrontal-/orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), nucleus accumbens shell (AcbSh) and paraventricular nucleus (PVN). The suppressed ethanol response in the OFC and AcbSh, key regions involved in ethanol preference and seeking, was restored by pre-treatment with UO126, demonstrating a recruitment of an ERK/MEK mediated inhibitory regulation in the post-dependent state. Conversely, in brain areas involved in stress responses (MeA, PVN), a MEK/ERK mediated cellular activation by acute ethanol was lost following a history of dependence.

These data reveal region-specific neuroadaptations encompassing the MEK/ERK pathway in ethanol dependence. Recruitment of MEK/ERK mediated suppression of the ethanol response in OFC and AcbSh may reflect devaluation of ethanol as a reinforcer, while loss of a MEK/ERK mediated response in MeA and PVN may reflect tolerance to its aversive actions. These two neuroadaptations could act in concert to facilitate progression into ethanol dependence.

Keywords: Alcoholism, animal model, mitogen-activated protein kinase, immediate early genes, extended amygdala, in situ hybridization

Introduction

Transition to ethanol dependence involves long-term neuroadaptations that lead to excessive voluntary ethanol intake and altered responses to stress (Heilig & Koob, 2007). Long-lasting neural and behavioral plasticity thought to model this process has been observed in laboratory rats following a history of dependence induced by prolonged exposure to ethanol vapor. Repeated cycles of intoxication and withdrawal, which mimic the course of the clinical condition is the most effective paradigm for inducing these long-term neuroadaptations, together labeled as “the post-dependent state” (Roberts et al, 2000; Rimondini et al, 2002; Rimondini et al, 2003; O'Dell et al, 2004; Valdez & Koob, 2004; Breese et al, 2005; Sommer et al, 2007).

The post-dependent state is associated with a stable up-regulation in the expression of several genes encoding members of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways in the prefrontal cortex (Rimondini et al, 2002). Elevated expression of several MAP kinases has also been found in the nucleus accumbens of a genetically selected alcohol preferring rat line (Arlinde et al, 2004). MAP kinase pathways, i.e. mitogen-activated and extracellular regulated kinase (MEK) and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK), have previously been implicated in the development of drug dependence. Inhibition of ERK attenuates cocaine-induced hyper-locomotion and antagonizes cocaine-induced expression of the immediate early gene (IEG) c-fos (Valjent et al, 2000), while ERK1 null mutants show increased sensitivity to the rewarding properties of morphine (Mazzucchelli et al, 2002). Effects of ethanol on MEK/ERK signaling are more complex. A decrease in phosphorylated ERK in the brain was found during ethanol exposure, while ERK phosphorylation increased during withdrawal (Sanna et al, 2002; Roberto et al, 2003; Chandler & Sutton, 2005). However, little is known about long-term regulation of MEK/ERK signaling following a history of dependence, and its possible role in the behavioral phenotype observed in the post-dependent state.

Stimulus dependent activation of marker genes such as c-fos and erg-1 is in part mediated by MAP kinase pathways (Bachtell et al, 2002; Schuck et al, 2003). The induction of these IEGs is mainly observed in neurons (Chaudhuri et al, 1995; Tsai et al, 2000; Hansson et al, 2003) and is stimulus-specific to a degree that allows classification of psychoactive drugs (Sumner et al, 2004). In rodents, acute ethanol administration at moderate doses is consistently reported to induce c-fos expression both in regions associated with aversion, stress responses, and sensory information processing (e.g. central amygdala (CeA), hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), and Edinger-Westphal nucleus, respectively (Ryabinin et al, 1997), and in regions thought to be involved in positive drug reinforcement such as ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex (Zoeller & Fletcher, 1994; Chang et al, 1995; Hitzemann & Hitzemann, 1997; Ryabinin et al, 1997; Bachtell et al, 2002; McBride, 2002; Crankshaw et al, 2003).

We reasoned that the expression of c-fos and egr-1 after acute ethanol challenge, administered in the presence or absence of the MEK1/2 inhibitor UO126, would delineate structures differentially involved in the initial ethanol response in dependent and non-dependent animals, respectively, and would thus serve as a marker for neuroadaptive processes associated with the development of the dependent state. We focused particularly on forebrain structures known to be involved in the mediation of drug seeking, positive and negative drug reinforcement.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (Møllegård, Denmark) were 220−250g at the beginning of the experiment, housed 4/cage under reversed light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. All experimental procedures using animals were carried out under the National Animal Welfare Act and were approved by the local ethical committees (Stockholm South Animal Ethics Committee, ethics permits S84/98).

Drugs

MEK1/2 inhibitor, UO126 (1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene, Calbiochem, CA, USA) was solved in different concentrations (1.25, 2.5 and 5 nmol) in 4 % DMSO and 0.9 % saline according to Coogan & Piggins (Coogan & Piggins, 2003). UO126 in 4% DMSO was pre-warmed prior to icv injection in order to prevent precipitations. UO126 inhibition is noncompetitive with respect to MEK substrates, ATP and ERK (Calbiochem, CA, USA).

Animal procedures

All rats were unilaterally implanted with guide cannulae into the right lateral ventricle (Coordinates: Bregma posterior (A) 0.8 mm, lateral (L) 1.4 mm, ventral (V) 4.3 mm, according to the atlas of (Paxinos & Watson, 1998) and were afterwards handled for 5 minutes daily for 10 days.

For in situ hybridization rat brains were quickly removed, snap frozen in liquid − 40°C isopentane and stored in −70°C. 10 μm coronal brain sections were cryo-sectioned at forebrain bregma levels +2.0 mm,−1.8 mm and −3.0 mm ((Paxinos & Watson, 1998), figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the sampled areas for the densitometric evaluation of mRNAs in a coronal section through the rat forebrain at Bregma levels +2 to −3 mm. Cingulate cortex (cg); frontal motor cortex (M1); primary sensory cortex (S1); infralimbic cortex (IL); orbitofrontal cortex (OFC); nucleus accumbens core (AcbC); nucleus accumbens shell (AcbSh); central amygdaloid nucleus (CeA); medio amygdaloid nucleus (MeA); basolateral amygdaloid nucleus (BLA); dorsal hippocampal subregions (CA: Cornus Ammon areas, CA1 to CA4; dentate gyrus, (DG); supraoptic nucleus (SO); hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN).

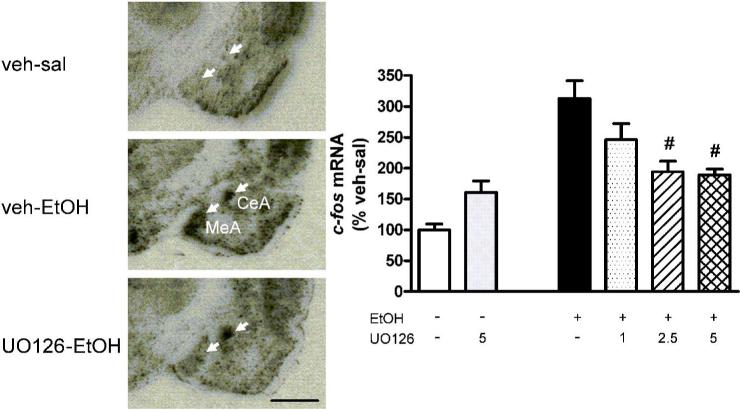

In preliminary experiments we established the effects of UO 126 (1, 2.5, 5 nmol, injected icv) and vehicle (4 % DMSO in 0.9 % saline, injection volume = 5 μl, injection time = 5 min) on ethanol-induced c-fos expression in ethanol-naïve Wistar rats. With the exception of the medial amygdala we found no effects of UO126 on ethanol induced c-fos expression (see figure 2). Because an apparent lack of UO126 effect could have been caused by a low MEK response to ethanol, insufficient diffusion of the inhibitor to sites of action, or both, a control experiment was carried using the robust phospho-ERK response to systemic amphetamine (10 mg/kg) as positive control. UO126 (2.5 nmol in 4% DMSO) administered icv effectively blocked amphetamine-induced phospho-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity in the primary motor cortex at Bregma 2.5 mm (see Supplementary Material).

Figure 2.

Right: Bar graph illustrating c-fos expression in the medial amygdala after UO 126 (1, 2.5 and 5 nmol, icv) and EtOH (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) treatment in naïve Wistar rats. Corrected p-values: ***p < 0.001 vs veh-sal group, #p < 0.05 vs veh-EtOH control group.

Left: Bright-field microphotographs from autoradiograms of in situ hybridization of c-fos mRNA in the amygdala region after UO126 (5 nmol, icv) and EtOH (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) treatment in naïve Wistar rats. Arrows indicate c-fos mRNA in MeA and CeA. c-fos mRNA levels are increased in both MeA and CeA after ethanol challenge and decreased in MeA after UO126 treatment. UO 126 treatment show no effect on ethanol-c-fos in CeA, scale bar = 1 mm, for abbreviations see figure 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods

Animal experiment I

In order to make animal experiments I and II comparable all rats were injected icv with vehicle. Thirty min after icv injections rats were injected i.p. with either a moderate dose of ethanol (1.5 g/kg, see (Ryabinin et al, 1997)) or 0.9 % saline.

Ethanol vapor exposure

Procedures were carried out as described previously in (Rimondini et al, 2002). Exposure was: 1 week of habituation to the chambers (no alcohol), 1 week of continuous exposure to 22 mg/L alcohol to adapt to the novel odor, 7 weeks of exposure to alcohol vapor adjusted to produce BACs of 150−320 mg/dl for 17 hours (4 pm-9 am) each day. Once a week during exposure, rats were weighed and blood was collected from the tail veins. Control rats were housed under the same conditions, except for the addition of ethanol vapor to the air flow. Alcohol vapor exposure was followed by a 3-week period of abstinence in order to eliminate effects of acute withdrawal. After 2 weeks of the abstinence period, a random subgroup of rats from each condition was selected for assessment of voluntary ethanol drinking, and placed in single cages for 1 week to habituate to this new environment, and reduce potential stress-induced effects on drinking.

Two bottle free choice

Following completion of the abstinence period, increasing concentrations of ethanol were made available as described previously, in a 0.2% saccharin solution, as continuous two-bottle free-choice between the ethanol-saccharin and saccharin alone solution. Briefly, ethanol concentration was increased as follows: day 1−3: 2% ethanol; day 4−7: 4% ethanol; from day 8: 6% ethanol (v/v solutions). Consumption of ethanol-saccharin and saccharin alone were measured Monday, Wednesday and Friday at the same time. Bottle positions were alternated daily to avoid development of side preference.

Animal experiment II

Ethanol vapor exposed and control rats were unilaterally implanted with cannula guide and handled as described above. Based on the results of the initial experiment, ethanol vapor exposed and age-matched control rats were icv injected with either UO126 (2.5 nmol) or vehicle alone using the same injection volume and injection time as described under experiment I. 30 min after icv injections all animal groups received the same dose of ethanol (i.p., 1.5 g/kg) as used in experiment I.

Rats from both animal experiment I and II were decapitated 45 min after the last injection and trunk blood were collected for blood alcohol and plasma corticosterone measurements.

Radioimmunoassay for corticosterone

Trunk blood was collected in heparine containing tubes and centrifuged at 2000 x g for 20 min at 4°C. Plasma CORT levels were determined by radioimmunoassay (RIA; Coat-a-count, Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA). The RIA was performed with rat [125I]CORT and had a detection limit of ∼ 5.7 ng/ml.

Blood alcohol concentration

Plasma was assayed for ethanol using an Analox system (Analox Instruments, Ltd., Lunenburg, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In situ hybridization

The rat specific riboprobes for c-fos (gene reference sequence in PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/): NM_022197.1, position 306 bp to 864 bp) and the egr-1 (gene reference sequence in PubMed database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Entrez/): NM_012551.1, position 1384 bp to 1851 bp) and the in situ hybridization have been recently described (Hansson et al, 2003; Hansson et al, 2006). Phosphor imaging plates (Fuji-film for BAS-5000, Fujifilm corp., Japan) were exposed for 48 hours to hybridized sections. Phosphor imager (Fujifilm Bio-Imaging Analyzer Systems, BAS-5000, Fujifilm corp., Japan) generated digital images were analyzed using MCID Image Analysis Software (Imaging Research Inc., UK). Regions of interest were defined by anatomical landmarks as described in the atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 1998) and illustrated in figure 1. Based on the known radioactivity in the 14C standards, image values were converted to nCi/g. For detailed visualization, slides were subsequently exposed for 1 month to Kodak BioMax MR film (Eastman Kodak Company, UK).

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical studies another set of normal male Wistar rats were cannulated as described above. 10 days after surgery rats received icv either UO126 (2.5 nmol) or vehicle (veh, 4 % DMSO). 30 min later rats were ip injected with either amphetamine (amph, 10 mg/kg) or saline (sal) and 15 min later sacrificed for phospho-ERK immunohistochemistry by intracardially perfusion with ice-cold saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. Immunohistochemistry was carried out as described in (Hansson et al, 2003) using the polyclonal rabbit anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK antibody (1:250, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Boston, USA). The immunostaining for phospho-ERK is similar to (Cai et al, 2000).

Statistics

Ethanol consumption is expressed as amount ethanol ingested per day (g/kg/day). All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Data met assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances, and were analyzed using standard parametric ANOVA. Region-wise one-way ANOVAs were used to identify ethanol responsive regions for c-fos and egr-1 expression in experiment I. Correction was made by Holm's sequential rejective testing procedure with respect to the 16 analyzed brain regions (Holm, 1979). Only ethanol responsive regions as identified in experiment I was subjected to a two-way ANOVA for ethanol and UO126 effects in experiment II. In cases where the test suggested UO126 or interaction effects, a planned post-hoc procedure was carried out to test for significant effects between groups using Fishers PSLD. The number of these tests was added to the initial 16 tests to calculate the respective Holm's correction factor. Raw p-values are reported and significance is indicated at levels for α < 0.05, α < 0.01 or α < 0.001.

Results

Experiment I: Acute ethanol response in drug naïve animals

Forty-five min after acute systemic ethanol administration BACs in the ethanol treated groups were between 175 − 228 mg/dl.

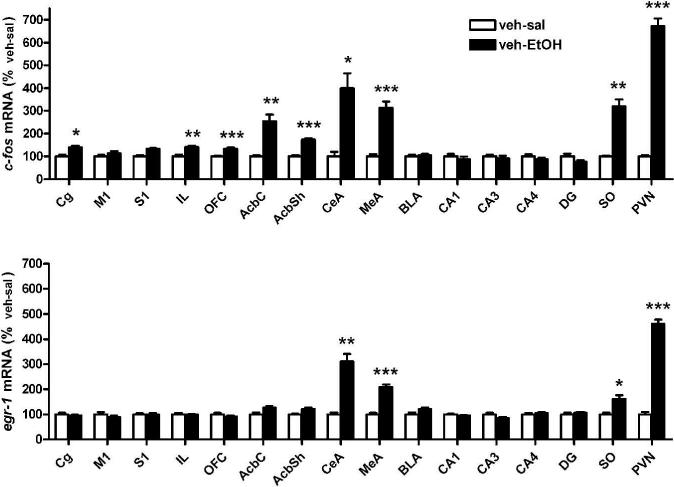

Significant induction of c-fos by ethanol was found in several cortical regions (anterior cingulate cortex, Cg, infralimbic cortex, IL, OFC), the nucleus accumbens (nucleus accumbens shell, AcbSh, and core, AcbC), the central and medial nuclei of the amygdala (CeA, MeA), and hypothalamic regions (supraoptic nucleus, SO, hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, PVN). The dorsal hippocampus and the basolateral amygdala were unaffected. The results and respective statistics are given in table 1 and illustrated in figure 3.

Table 1.

Effects of acute ethanol (EtOH, 1.5 g/kg, i.p.) on c-fos and egr-1 gene expression levels in different brain regions of naïve Wistar rats. Data are expressed as nCi/g (means ± S.E.M.), n=4−6/group, corrected p-values: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; vehicle (veh)-EtOH vs veh-saline (sal); for details on treatment see Material and Methods.

| Region | veh-sal | veh-EtOH | veh-sal | veh-EtOH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-fos | egr-1 | |||

| cg | 22.3 ± 1.7 | 31.5 ± 1.4* | 100.7 ± 5.6 | 96.0 ± 2.8 |

| M1 | 14.4 ± 1.0 | 16.2 ± 1.5 | 64.3 ± 5.6 | 57.2 ± 3.6 |

| S1 | 18.8 ± 1.0 | 25.1 ± 0.5 | 92.0 ± 3.3 | 92.4 ± 3.6 |

| IL | 25.8 ± 1.9 | 36.5 ± 1.5** | 64.0 ± 2.6 | 63.0 ± 1.6 |

| OFC | 20.3 ± 0.5 | 27.3 ± 1.0*** | 110.7 ± 5.9 | 100.9 ± 4.5 |

| AcbC | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 11.3 ± 1.3** | 26.6 ± 1.9 | 33.6 ± 1.9 |

| AcbSh | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 0.3*** | 40.1 ± 1.1 | 48.9 ± 2.0 |

| CeA | 4.7 ± 0.9 | 18.8 ± 3.1* | 19.5 ± 1.5 | 52.6 ± 9.4** |

| MeA | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 16.2 ± 1.5*** | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 32.7 ± 1.6*** |

| BLA | 9.8 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 35.4 ± 2.7 | 42.6 ± 2.1 |

| CA1 | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 109.9 ± 3.0 | 104.2 ± 2.2 |

| CA3 | 11.7 ± 0.8 | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 45.0 ± 2.4 | 38.1 ± 2.5 |

| CA4 | 14.4 ± 1.3 | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 41.6 ± 1.9 | 43.1 ± 2.2 |

| DG | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 26.2 ± 1.1 |

| SO | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 42.0 ± 4.0** | 18.5 ± 1.1 | 29.7 ± 2.8* |

| PVN | 37.9 ± 1.9 | 254.9 ± 13*** | 23.3 ± 2.2 | 107.6 ± 3.9*** |

Cingulate cortex (cg); frontal motor cortex (M1); primary sensory cortex (S1); infralimbic cortex (IL); orbitofrontal cortex (OFC); nucleus accumbens core (AcbC); nucleus accumbens shell (AcbSh); central amygdaloid nucleus (CeA); medio amygdaloid nucleus (MeA); basolateral amygdaloid nucleus (BLA); dorsal hippocampal subregions (CA: Cornus Ammon areas, CA1 to CA4; dentate gyrus, (DG); supraoptic nucleus (SO); hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), saline (sal), vehicle (veh).

Figure 3.

Ethanol induced c-fos (upper panel) and egr-1 (lower panel) expression in different forebrain regions of Wistar rats. Bar graphs illustrating c-fos and egr-1 expression 45 minutes after ethanol (EtOH, 1.5 g/kg, i.p., black bar) or saline (sal, i.p., white bar) injection in rats pretreated with vehicle (veh, 4 % DMSO, icv). Data are expressed as percent of control group (% veh-sal group, mean ± S.E.M.). Statistical analysis were performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Holms corrected Bonferroni's post-hoc test, n = 4−6/group, corrected p-values: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<001; for abbreviations see figure 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods.

Acute ethanol challenge had a less pronounced effect on egr-1 mRNA levels. Induction was found in the CeA and MeA as well as in the SO and PVN (table 1, fig. 3).

Experiment II: Effects of UO126 on ethanol induced marker gene expression in post-dependent animals

Similarly to our previous experiments (Rimondini et al., 2002), daily, 17-hour exposure to ethanol vapor induced BAC in the range of 150−250 mg/dl which fell to undetectable level within 5 hours during the ethanol-off period with detectable signs of mild withdrawal such as tail stiffness and piloerection towards the end of the 7-week exposure period. Withdrawal intensity did not reach seizure level.

Effects of intoxication procedure on ethanol consumption and corticosterone levels

After 3 weeks of abstinence, ethanol consumption was assessed in a randomly selected subgroup of rats. We found a greater than 2-fold increase in voluntary ethanol drinking in the two-bottle free-choice test of exposed rats vs. controls demonstrating long-lasting behavioral plasticity induced by the exposure paradigm (mean daily intake from ethanol bottle (6 % v/v): 2.6 ± 0.16 and 1.2 ± 0.21, F[1,19] = 55.6, p << 0.001 exposed vs control).

The remaining rats were implanted with icv cannula guides and familiarized with the experimental environment during the abstinence period. On the day of the experiment ethanol-dependent rats and controls were given UO126 (2.5 nmol) or vehicle followed by an acute ethanol challenge (1.5 mg/kg, i.p.). The doses of 2.5 nmol UO126 was chosen based on the results of the initial dose-response experiment (fig. 2). Rats were sacrificed 45 min after the last injection. At this time point, mean BACs were between 155 − 170 mg/dl without significant differences between the groups. However, plasma corticosterone levels were significantly lower in exposed vs control rats (two-way ANOVA; main exposure effect: F[1,24] = 9.7, p < 0.01, main UO126 effect: F[1,24] = 0.5, not significant (n.s.), and interaction: F[1,24] = 0.1, n.s.).

Ethanol induced c-fos and egr-1 expression in dependent rats

Transcript levels of c-fos were analyzed in ethanol responsive brain regions as identified by experiment I by two-way ANOVA for effects of history of dependence and UO126 treatment. Dependent rats showed a significantly attenuated induction of c-fos expression by ethanol in the Cg, IL, and OFC and in the PVN as demonstrated by post-hoc comparison between exposed-veh vs. control-veh (see tables 2, 3, fig. 4). No such effects were found in any region on egr-1 expression (tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Effects of MEK1/2 inhibitor UO126 (UO, 2.5 nmol, icv) and acute ethanol (1.5 g/kg, i.p.) on c-fos and egr-1 gene expression levels in different brain regions of 7 weeks cyclic ethanol exposed (exp) Wistar rats. Data are expressed as nCi/g (means ± S.E.M.), n=6−7/group; for abbreviations see table 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods.

| region | control-veh | control-UO | exp-veh | exp-UO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-fos | ||||

| cg | 95.2 ± 5.8 | 89.4 ± 3.5 | 75.6 ± 1.9 | 79.2 ± 3.8 |

| M1 | 25.8 ± 2.6 | 30.9 ± 2.2 | 23.4 ± 1.0 | 28.4 ± 1.9 |

| S1 | 68.7 ± 4.6 | 54.9 ± 4.4 | 68.0 ± 3.3 | 58.7 ± 5.7 |

| IL | 80.7 ± 4.9 | 67.4 ± 6.1 | 58.0 ± 3.3 | 62.9 ± 6.3 |

| OFC | 58.1 ± 2.9 | 59.7 ± 2.3 | 42.5 ± 2.0 | 67.6 ± 2.3 |

| AcbC | 24.8 ± 2.1 | 26.8 ± 1.9 | 21.8 ± 1.0 | 27.0 ± 1.7 |

| AcbSh | 12.5 ± 1.1 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 14.3 ± 1.0 |

| CeA | 83.0 ± 2.4 | 87.2 ± 3.3 | 92.2 ± 4.7 | 100.3 ± 9.4 |

| MeA | 53.8 ± 1.8 | 41.1 ± 2.0 | 45.6 ± 2.2 | 42.8 ± 3.4 |

| BLA | 55.1 ± 3.3 | 50.7 ± 1.9 | 60.4 ± 1.4 | 51.5 ± 2.2 |

| CA1 | 47.8 ± 3.6 | 26.3 ± 2.4 | 53.6 ± 2.6 | 47.8 ± 3.6 |

| CA3 | 77.5 ± 5.2 | 70.6 ± 5.2 | 80.4 ± 2.2 | 77.0 ± 5.3 |

| CA4 | 63.4 ± 2.6 | 52.0 ± 3.4 | 68.0 ± 1.8 | 66.4 ± 4.1 |

| DG | 52.5 ± 1.0 | 31.2 ± 5.7 | 55.2 ± 3.4 | 43.3 ± 7.4 |

| SO | 268.8 ± 12.7 | 276.1 ± 23.0 | 302.6 ± 20.6 | 172.5 ± 6.3 |

| PVN | 380.6 ± 27.2 | 318.7 ± 10.5 | 215.8 ± 21.2 | 244.8 ± 21.3 |

| egr-1 | ||||

| cg | 182.4 ± 7.5 | 189.6 ± 5.6 | 176.0 ± 5.1 | 183.5 ± 6.7 |

| M1 | 97.5 ± 3.4 | 105.6 ± 4.1 | 101.2 ± 5.4 | 101.5 ± 4.6 |

| S1 | 191.3 ± 2.2 | 167.9 ± 6.4 | 178.0 ± 5.9 | 176.9 ± 5.4 |

| IL | 93.5 ± 3.7 | 83.7 ± 4.7 | 76.9 ± 3.8 | 87.6 ± 3.9 |

| OFC | 125.6 ± 3.5 | 142.3 ± 3.7 | 132.7 ± 7.3 | 139.0 ± 5.5 |

| AcbC | 48.0 ± 2.0 | 73.9 ± 2.2 | 62.4 ± 2.3 | 64.7 ± 2.1 |

| AcbSh | 78.9 ± 1.7 | 98.2 ± 4.7 | 90.2 ± 0.8 | 92.0 ± 2.3 |

| CeA | 167.4 ± 15.5 | 129.9 ± 14.6 | 141.6 ± 14.7 | 137.2 ± 12.8 |

| MeA | 72.9 ± 4.8 | 61.6 ± 3.3 | 59.1 ± 4.8 | 59.0 ± 3.3 |

| BLA | 89.4 ± 2.8 | 83.3 ± 3.4 | 84.9 ± 4.3 | 80.9 ± 2.0 |

| CA1 | 164.4 ± 6.4 | 165.3 ± 6.2 | 180.1 ± 3.1 | 140.0 ± 4.2 |

| CA3 | 107.4 ± 7.7 | 116.9 ± 10.1 | 108.4 ± 6.9 | 106.4 ± 5.2 |

| CA4 | 94.7 ± 4.3 | 94.4 ± 5.8 | 90.8 ± 5.8 | 96.9 ± 4.9 |

| DG | 71.0 ± 3.4 | 68.9 ± 6.2 | 65.1 ± 4.1 | 71.5 ± 4.0 |

| SO | 125.0 ± 2.8 | 106.5 ± 8.1 | 105.8 ± 4.4 | 77.6 ± 5.3 |

| PVN | 143.8 ± 6.1 | 157.2 ± 11.8 | 93.9 ± 10.1 | 102.8 ± 11.7 |

Table 3.

Regions with statistically significant effects on c-fos and egr-1 expression in experiment II. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA in brain regions responding to a challenging dose of ethanol as identified in experiment I to assess ethanol vapor exposure (exp)—, MEK1/2 inhibitor UO126 (UO, 2.5 nmol, icv) effect as well as the interaction of ethanol vapor exposure and MEK1/2 inhibitor in rats i.p. injected with ethanol (1.5 g/kg). In order to correct for multiple tests with a FWER of 0.05 Holms corrected Bonferroni's post-hoc test was used for every planned comparison; corrected p-values: *#p < 0.05; **##p < 0.01; ***###p < 0.001; vehicle (veh); n.s. = not significant; n.t. = not tested; for abbreviations see table 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods.

| Region | contrast | F | Planned comparisons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | exp-veh vs. control-veh | control-UO vs. control-veh | exp-UO vs. exp-veh | |||

| c-fos | ||||||

| cg | exp | 15.1 [1,23] | 0.000737 | |||

| UO | 0.1 [1,23] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 1.5 [1,23] | n.s. | 0.001740* | n.s. | n.s. | |

| IL | exp | 6.7 [1,23] | 0.016139 | |||

| UO | 0.6 [1,23] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 3.0 [1,23] | n.s. | 0.004659* | n.s. | n.s. | |

| OFC | exp | 2.4 [1,22] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 29.4 [1,22] | 0.000019 | ||||

| exp x UO | 22.6 [1,22] | 0.000095 | 0.000116** | n.s. | 0.000001### | |

| AcbC | exp | 0.7 [1,24] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 4.2 [1,24] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 0.9 [1,24] | n.s. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | |

| AcbSh | exp | 0.1 [1,23] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 4.0 [1,23] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 8.0 [1,23] | 0.009697 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.002002# | |

| CeA | exp | 3.4 [1,22] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 1.0 [1,22] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 0.1 [1,22] | n.s. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | |

| MeA | exp | 1.7 [1,23] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 9.8 [1,23] | 0.004748 | ||||

| exp x UO | 4.0 [1,23] | n.s. | 0.032436 | 0.001722# | n.s. | |

| SO | exp | 4.5 [1,19] | 0.048160 | |||

| UO | 13.8 [1,19] | 0.001462 | ||||

| exp x UO | 17.3 [1,19] | 0.000533 | n.s. | n.s. | 0.000018### | |

| PVN | exp | 37.0 [1,16] | 0.000016 | |||

| UO | 0.7 [1,16] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 5.4 [1,16] | 0.034302 | 0.000036*** | 0.042449 | n.s. | |

| egr-1 | ||||||

| CeA | exp | 0.4 [1,22] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 2.1 1,22] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 1.3 [1,22] | n.s. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | |

| MeA | exp | 4.0 [1,23] | n.s. | |||

| UO | 1.9 [1,23] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 1.9 [1,23] | n.s. | n.t. | n.t. | n.t. | |

| SO | exp | 16.4 [1,22] | 0.000535 | |||

| UO | 15.4 [1,22] | 0.000720 | ||||

| exp x UO | 0.7 [1,22] | n.s. | 0.039708 | 0.047051 | 0.001928# | |

| PVN | exp | 20.9 [1,16] | 0.000311 | |||

| UO | 1.0 [1,16] | n.s. | ||||

| exp x UO | 0.04 [1,16] | n.s. | 0.012196 | n.s. | n.s. | |

Figure 4.

A: Bar graphs are illustrating the effects of MEK inhibitor UO126 (2.5 nmol, icv) or vehicle (4 % DMSO, icv) on ethanol (1.5 g/kg, i.p)-induced c-fos mRNA in different forebrain regions of rats with a history of ethanol dependence and age-matched controls. Corrected p-values: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vehicle treated ethanol exposed vs vehicle treated control group, #p < 0.05, ###p < 0.001 UO treated group vs corresponding ethanol exposed or control group. B: Bright-field microphotographs from autoradiograms of in situ hybridization are showing the effects of MEK inhibitor UO126 (2.5 nmol, icv) on ethanol (1.5 g/kg, i.p.)-induced c-fos mRNA levels in the OFC, SO and PVN region of rats with a history of ethanol dependence and vehicle treated age-matched control rats, scale bar = 1 mm; for abbreviations see figure 1, for details on treatment, see Material and Methods.

In post-dependent rats UO126 (2.5 nmol) increased c-fos expression in the OFC, the AcbSh and decreased c-fos in the SO (post-hoc comparison between exposed-UO126 vs control-veh groups, tables 3, 4, fig. 4). Notably, the only UO126 sensitive region in non-dependent rats, the MeA, showed no effect in ethanol vapor exposed rats (table 2, fig. 4). Furthermore, UO126 treatment in dependent rats decreased significantly egr-1 in the SO (tables 3, 4).

Discussion

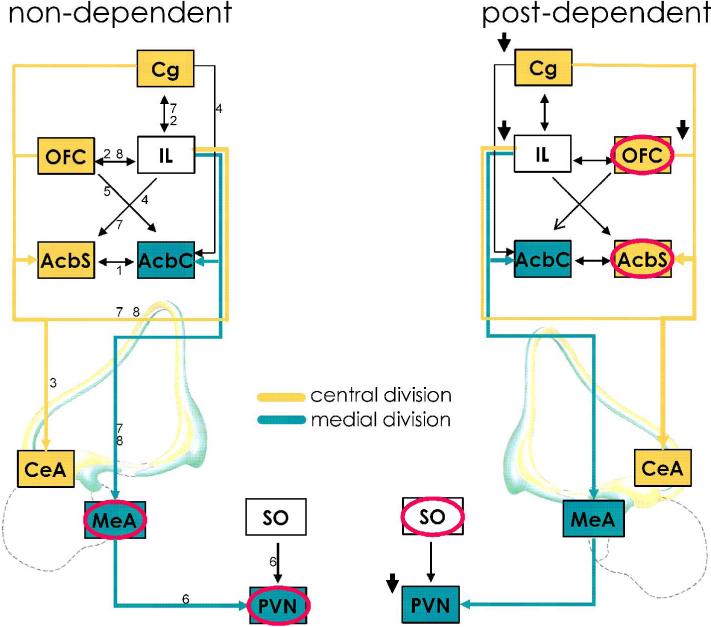

With exception of MeA and to some extent the PVN, we found that ethanol induced neuronal activation as probed by c-fos and egr-1 expression is generally not affected by UO126 in non-dependent animals. In contrast, following a history of dependence, ERK pathways are recruited and suppress the cellular response to ethanol in OFC and AcbSh, brain regions known to mediate drug seeking and positive reinforcement. Conversely, the MEK/ERK mediated cellular response to ethanol originally present in MeA and PVN, likely related to the behavioral and endocrine stress response to ethanol, is lost (summarized in fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation summarizing the results on ethanol-induced c-fos expression and its interaction with the ERK1/2 kinase signaling pathway in brain regions related to the extended amygdala (adapted from(Heimer, 2003)). Only those regions are shown that react in non-dependent rats (left) with increased c-fos to an acute ethanol challenge. Under non-dependent conditions, ethanol-induced c-fos expression was generally not affected by MEK inhibition, with the exception of the MeA (red circles), and to a lesser extend the PVN. Post-dependent rats (right) show reduced c-fos induction in the prefrontal cortex (Cg, IL, OFC) and the PVN upon ethanol challenge (indicated by short bold arrows) compared to non-dependent controls which probably is a correlate of tolerance to the drug. UO126 markedly increased c-fos expression in OFC and AcbSh, key components of circuitry mediating positive drug reinforcement, demonstrating a recruitment of an ERK mediated inhibitory regulation in the post-dependent state. Thus, positive MEK/ERK-ethanol interactions are related to the central division and negative interactions to the medial division of the extended amygdala. Beside anatomical evidences of a division of the extended amygdala into a central- and medial part (Alheid, 2003; Heimer, 2003) our results support the idea of a corresponding functional divisions, i.e. devaluation of ethanol as a reinforcer and tolerance to its aversive actions, respectively, which may both take part in the development of ethanol dependence. Brain regions anatomically or functionally related to the central or the medial divisions of the extended amygdala are colored in yellow or in blue, respectively, and their efferents/afferents are indicated as arrows with respective color. Black arrows indicate other connections between the regions. For abbreviations see figure 1, and for details on treatment, see Material and Methods. 1(van Dongen et al, 2005), 2(Hoover & Vertes, 2007), 3(McDonald et al, 1996), 4(Reynolds & Zahm, 2005), 5(Schoenbaum & Setlow, 2003), 6(Silverman et al, 1981), 7(Vertes, 2004), 8(Vertes, 2006)

Ethanol effects on marker gene expression in the forebrain of drug naïve animals

We observed c-fos responses to acute ethanol in prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, centro-medial amygdala and hypothalamic regions. This pattern is likely to reflect simultaneous activation by ethanol of structures that mediate its reinforcing, as well as stress-like actions. Our results are in general agreement with previous studies on ethanol-induced c-Fos-immunoreactivity (Chang et al, 1995; Hitzemann & Hitzemann, 1997; Ryabinin et al, 1997; Ryabinin & Wang, 1998; Knapp et al, 2001; McBride, 2002; Herring et al, 2004) and demonstrate a distinct c-fos response profile that is different from other psychoactive drugs.

It has been shown that c-fos activation patterns allow classification of drugs according to their neurochemical mechanism of action (Sumner et al, 2004). For instance, psychostimulants seem to consistently activate c-fos in prefrontal and striatal regions, and this effect is likely to be mediated via dopamine. The specific activation pattern caused by ethanol likely reflects that this drug acts via a broader range of neurotransmitter systems. Thus, like psychostimulants ethanol induces c-fos in prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum, but lacks their action in the caudate putamen. Simultaneously, ethanol also induces c-fos in regions involved in processing of negative emotions and stress responses, which show consistent c-fos activation by antidepressants and some anxiolytics (Sumner et al, 2004). Ethanol's c-fos profile is also different from that of acute opioid and endocannabinoid action on this gene (Garcia et al, 1995; Gutstein et al, 1998; Erdtmann-Vourliotis et al, 1999; Valjent et al, 2001; Derkinderen et al, 2003), although these neurotransmitter systems appear to play a key role in mediating the positively reinforcing properties of ethanol. In summary, most drugs of abuse including ethanol induce c-fos in the nucleus accumbens, but show very different activation patterns in other brain regions.

The egr-1 response to acute ethanol paralleled in a less pronounced manner the pattern of cfos expression. In contrast to c-fos, egr-1 has a high basal expression in many brain regions, and may because of that be less sensitive to induction. The discordance in the regulation of cfos and erg-1 may also reflect that different neuronal cell populations express these IEGs and that these are differentially sensitive to ethanol challenge. For example, egr-1 was found to be expressed in excitatory, but not inhibitory cortical neurons (Ponomarev et al, 2006).

Role of ERK1/2 in ethanol-induced marker gene expression in non-dependent animals In contrast to c-fos, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 shows a more consistent pattern upon acute challenge with addictive drugs, including amphetamine, cocaine, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, nicotine, and morphine. All of those cause strong phosphorylation of ERK in prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, BNST and CeA (for review see (Lu et al, 2006; Zhai et al, 2007; Girault et al, 2007). A number of studies have shown that MEK/ERK signaling regulates both c-fos and egr-1 expression (reviewed by (Davis, 1995; Seger & Krebs, 1995; Kaufmann et al, 2001), and the ERK activation observed after administration of drugs of abuse other than ethanol is likely a key signal for induction of these genes. Ethanol appears to fundamentally differ from other drugs of abuse in that the MEK/ERK cascade does seem not mediate ethanol-induce c-fos and egr-1 expression, found to be insensitive to the inhibitor in non-dependent animals. These observations are in agreement with and predicted by studies which show that acute ethanol, rather than activating ERK phosphorylation suppresses it in a wide range of brain regions, including cerebral cortex, nucleus accumbens and hippocampus (Davis et al, 1999; Kalluri & Ticku, 2002; Chandler & Sutton, 2005; Neznanova et al, 2007).

The one exception to this pattern was found in the MeA, where UO126 significantly blocked ethanol induced c-fos (but not egr-1) expression. This MeA-specific effect points to an important functional differentiation between the CeA and the MeA in the mediation of ethanol effects. The importance of the CeA in mediating autonomic and behavioral responses to aversive stimuli is well established (Davis, 1992; Möller et al, 1997). Although less is known about the MeA, this structure seems to modulate defensive behavior (Dielenberg et al, 2001; Blanchard et al, 2005). Lesions of the MeA, but not of the CeA, markedly reduce immediate defensive responses, such as freezing and assessment behaviors. Furthermore, the amount of freezing seems to be correlated with c-fos expression in the MeA (Chen et al, 2006). Thus, this structure has a highly specialized role in emotional processing, and effects of alcohol here may provide a substrate for altered processing of emotional stimuli in alcoholics. Similar to the CeA, the MeA projects to the medial hypothalamus. In fact, it has been pointed out that medial rather than central amygdala is critical for the activation of the HPA axis in response to emotional stressors (Dayas et al, 1999). Notably, the strongest induction of both marker genes by ethanol in the present study was found in the PVN. Here, MEK/ERK inhibition seemed to have a trend effect on ethanol-induced c-fos expression. Together with the MeA finding, these data suggest that MEK/ERK signaling in non-dependent animals is most likely involved in the response to ethanol as a stressor (fig. 5).

Neuroadaptations following ethanol dependence

Following a history of dependence, we found a recruitment of inhibitory MEK/ERK signaling in OFC and AcbSh, two structures intimately involved in drug seeking and ethanol preference, respectively (Kalivas et al, 2005; Schoenbaum & Shaham, 2008). In the non-dependent state, the c-fos response to an acute ethanol challenge in these structures was robust, and insensitive to UO126. In contrast, in post-dependent animals, this response was markedly suppressed but was restored by pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor. This provides evidence for a functional recruitment of MAPK signaling in the post-dependent state, and may be a correlate of the up-regulated MAPK expression previously found under these conditions (Rimondini et al, 2002). Recruitment of inhibitory mechanisms within OFC– nucleus accumbens circuitry (Homayoun & Moghaddam, 2006) may result in a devaluation of ethanol reward, and thus contribute to escalation of drug intake.

The opposite pattern was observed within structures related to stress responses, where ethanol responses found in non-dependent animals where absent or attenuated following a history of dependence. Thus, the ERK-dependent c-fos response to acute ethanol found in the MeA of non-dependent rats was eliminated following a history of dependence. A very similar pattern was seen within the hypothalamic PVN. Together, these data suggest tolerance to ethanol effects within stress-responsive circuitry following a history of dependence. This is in line with neuroendocrine data demonstrating attenuated HPA-axis function in post-dependent animals, and the suggestion that HPA axis develops tolerance to the effects of ethanol (Rivier et al, 1990; Zorrilla et al, 2001). Progressive attenuation of ethanol induced stress responses may remove a break on excessive ethanol intake, and serve as a permissive factor in development of dependence.

Conclusions

We show that excessive voluntary ethanol intake observed following a history of dependence is accompanied by long-term plasticity of neuronal circuitries mediating acute ethanol effects. ERK pathways within structures that mediate positive and negative drug reinforcement, respectively, are differentially affected by dependence induced plasticity. Within the former, inhibitory ERK influence is recruited in a manner that may attenuate ethanol reward and lead to compensatory escalation of ethanol intake. Within the latter, tolerance to an acute ethanol challenge evolves, and may be mediated by a down-regulation of ERK-mediated responses, in particular within medial amygdala. This may contribute to the development of dependence by removing a break on excessive ethanol intake.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by intramural NIAAA funding, funding from the Swedish Medical Research Council, and the Karolinska Institute. The authors thank Bob Rawlings for help with the statistical analysis, Beth Andbjer and April Honeycutt for technical assistance.

Supplementary Material

Schematic representation of the primary motor cortex (M1) in a rat coronal brain section at Bregma level +2.5 mm. Right. Amphetamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 immunoreactivity (ir) in M1 following pretreatment with UO126. Immunohistochemistry for phospho-ERK1/2 clearly demonstrates an increase of phospho-ERK1/2-ir after amphetamine (amph, 10 mg/kg, ip) which is blocked by UO126 (UO, 2.5 nnol, icv) pretreatment. Thus, after icv injection UO seems to penetrate the tissue in sufficient concentration to block the phosphorylation of ERK1/2; saline (sal), vehicle (veh, 4% DMSO, icv); for details, see Materials and Methods.

Reference List

- 1.Alheid GF. Extended amygdala and basal forebrain. Amygdala in Brain Function: Bacic and Clinical Approaches. 2003;985:185–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arlinde C, Sommer W, Bjork K, Reimers M, Hyytia P, Kiianmaa K, Heilig M. A cluster of differentially expressed signal transduction genes identified by microarray analysis in a rat genetic model of alcoholism. Pharmacogenomics J. 2004;4:208–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachtell RK, Tsivkovskaia NO, Ryabinin AE. Alcohol-induced c-Fos expression in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus: pharmacological and signal transduction mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:516–524. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.036046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard DC, Canteras NS, Markham CM, Pentkowski NS, Blanchard RJ. Lesions of structures showing FOS expression to cat presentation: Effects on responsivity to a Cat, Cat odor, and nonpredator threat. Neurosci.Biobehav.Rev. 2005;29:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breese GR, Overstreet DH, Knapp DJ. Conceptual framework for the etiology of alcoholism: a “ kindling”/stress hypothesis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;178 doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai G, Zhen X, Uryu K, Friedman E. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases is associated with a sensitized locomotor response to D(2) dopamine receptor stimulation in unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. J.Neurosci. 2000;20:1849–1857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01849.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandler LJ, Sutton G. Acute ethanol inhibits extracellular signal-regulated kinase, protein kinase B, and adenosine 3 ′ : 5 ′-cyclic monophosphate response element binding protein activity in an age- and brain region-speciric manner. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:672–682. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158935.53360.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang SL, Patel NA, Romero AA. Activation and desensitization of Fos immunoreactivity in the rat brain following ethanol administration. Brain Res. 1995;679:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00210-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaudhuri A, Matsubara JA, Cynader MS. Neuronal-Activity in Primate Visual-Cortex Assessed by Immunostaining for the Transcription Factor Zif268. Vis.Neurosci. 1995;12:35–50. doi: 10.1017/s095252380000729x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SWC, Shemyakin A, Wiedenmayer CP. The role of the amygdala and olfaction in unconditioned fear in developing rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:233–240. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2890-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coogan AN, Piggins HD. Circadian and photic regulation of phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Elk-1 in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the Syrian hamster. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:3085–3093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-03085.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crankshaw DL, Briggs JE, Olszewski PK, Shi Q, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Effects of intracerebroventricular ethanol on ingestive behavior and induction of c-Fos immunoreactivity in selected brain regions. Physiol.Behav. 2003;79:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 1992;15:353–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis MI, Szarowski D, Turner JN, Morrisett RA, Shain W. In vivo activation and in situ BDNF-stimulated nuclear translocation of mitogen-activated/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase is inhibited by ethanol in the developing rat hippocampus. Neurosci.Lett. 1999;272:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis RJ. Transcriptional regulation by MAP kinases. Mol.Reprod.Dev. 1995;42:459–467. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080420414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dayas CV, Buller KM, Day TA. Neuroendocrine responses to an emotional stressor: evidence for involvement of the medial but not the central amygdala. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:2312–2322. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Derkinderen P, Valjent E, Toutant M, Corvol JC, Enslen H, Ledent C, Trzaskos J, Caboche J, Girault JA. Regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by cannabinoids in hippocampus. J.Neurosci. 2003;23:2371–2382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02371.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dielenberg RA, Hunt GE, McGregor IS. ‘When a rat smells a cat’: The distribution of Fos immunoreactivity in rat brain following exposure to a predatory odor. Neuroscience. 2001;104:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdtmann-Vourliotis M, Mayer P, Riechert U, Hollt V. Acute injection of drugs with low addictive potential (delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diamide) causes a much higher c-fos expression in limbic brain areas than highly addicting drugs (cocaine and morphine). Brain Res.Mol.Brain Res. 1999;71:313–324. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia MM, Brown HE, Harlan RE. Alterations in immediate-early gene proteins in the rat forebrain induced by acute morphine injection. Brain Res. 1995;692:23–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00625-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Girault JA, Valjent E, Caboche J, Herve D. ERK2: a logical AND gate critical for drug-induced plasticity? Curr.Opin.Pharmacol. 2007;7:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutstein HB, Thome JL, Fine JL, Watson SJ, Akil H. Pattern of c-fos mRNA induction in rat brain by acute morphine. Can.J.Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;76:294–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansson AC, Cippitelli A, Sommer WH, Fedeli A, Bjork K, Soverchia L, Terasmaa A, Massi M, Heilig M, Ciccocioppo R. Variation at the rat Crhr1 locus and sensitivity to relapse into alcohol seeking induced by environmental stress. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;103:15236–15241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604419103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansson AC, Sommer W, Rimondini R, Andbjer B, Stromberg I, Fuxe K. c-fos reduces corticosterone-mediated effects on neurotrophic factor expression in the rat hippocampal CA1 region. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6013–6022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06013.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heilig M, Koob GF. A key role for corticotropin-releasing factor in alcohol dependence. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heimer L. A new anatomical framework for neuropsychiatric disorders and drug abuse. Am.J.Psychiatry. 2003;160:1726–1739. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herring BE, Mayfield RD, Camp MC, Alcantara AA. Ethanol-induced fos immunoreactivity in the extended amygdala and hypothalamus of the rat brain: Focus on cholinergic interneurons of the nucleus accumbens. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:588–597. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122765.58324.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hitzemann B, Hitzemann R. Genetics, ethanol and the Fos response: A comparison of the C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mouse strains. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:1497–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Homayoun H, Moghaddam B. Progression of cellular adaptations in medial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex in response to repeated amphetamine. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:8025–8039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0842-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoover WB, Vertes RP. Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct.Funct. 2007;212:149–179. doi: 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalivas PW, Volkow N, Seamans J. Unmanageable motivation in addiction: a pathology in prefrontal-accumbens glutamate transmission. Neuron. 2005;45:647–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalluri HS, icku MK. Ethanol-mediated inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylation in mouse brain. Eur.J.Pharmacol. 2002;439:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann K, Bach K, Thiel G. The extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases Erk1/Erk2 stimulate expression and biological activity of the transcriptional regulator Egr-1. Biol.Chem. 2001;382:1077–1081. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knapp DJ, Braun CJ, Duncan GE, Qian Y, Fernandes A, Crews FT, Breese GR. Regional specificity of ethanol and NMDA action in brain revealed with FOS-like immunohistochemistry and differential routes of drug administration. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:1662–1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu L, Koya E, Zhai H, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ERK in cocaine addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzucchelli C, Vantaggiato C, Ciamei A, Fasano S, Pakhotin P, Krezel W, Welzl H, Wolfer DP, Pages G, Valverde O, Marowsky A, Porrazzo A, Orban PC, Maldonado R, Ehrengruber MU, Cestari V, Lipp HP, Chapman PF, Pouyssegur J, Brambilla R. Knockout of ERK1 MAP kinase enhances synaptic plasticity in the striatum and facilitates striatal-mediated learning and memory. Neuron. 2002;34:807–820. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McBride WJ. Central nucleus of the amygdala and the effects of alcohol and alcohol-drinking behavior in rodents. Pharmacol Biochem.Behav. 2002;71:509–515. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00680-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDonald AJ, Mascagni F, Guo L. Projections of the medial and lateral prefrontal cortices to the amygdala: a Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Neuroscience. 1996;71:55–75. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Möller C, Wiklund L, Sommer W, Thorsell A, Heilig M. Decreased experimental anxiety and voluntary ethanol consumption in rats following central but not basolateral amygdala lesions. Brain Res. 1997;760:94–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neznanova O, Sommer WH, Rimondini R, Hansson AC, Hyyatia P, Heilig M. Signal transiduction in alcohol-preferring AA and alcohol-avoiding ANA rat lines. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(6):193A. Ref Type: Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Dell LE, Roberts AJ, Smith RT, Koob GF. Enhanced alcohol self-administration after intermittent versus continuous alcohol vapor exposure. Alcohol Clin.Exp.Res. 2004;28:1676–1682. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000145781.11923.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponomarev I, Maiya R, Harnett MT, Schafer GL, Ryabinin AE, Blednov YA, Morikawa H, Boehm SL, Homanics GE, Berman A, Lodowski KH, Bergeson SE, Harris RA. Transcriptional signatures of cellular plasticity in mice lacking the alpha 1 subunit of GABA(A) receptors. J.Neurosci. 2006;26:5673–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0860-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds SM, Zahm DS. Specificity in the projections of prefrontal and insular cortex to ventral striatopallidum and the extended amygdala. J.Neurosci. 2005;25:11757–11767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rimondini R, Arlinde C, Sommer W, Heilig M. Long-lasting increase in voluntary ethanol consumption and transcriptional regulation in the rat brain after intermittent exposure to alcohol. FASEB J. 2002;16:27–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0593com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rimondini R, Sommer W, Heilig M. A temporal threshold for induction of persistent alcohol preference: behavioral evidence in a rat model of intermittent intoxication. J Stud.Alcohol. 2003;64:445–449. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rivier C, Imaki T, Vale W. Prolonged Exposure to Alcohol - Effect on Crf Messenger-Rna Levels, and Crf-Induced and Stress-Induced Acth-Secretion in the Rat. Brain Research. 1990;520:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91685-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roberto M, Nelson TE, Ur CL, Brunelli M, Sanna PP, Gruol DL. The transient depression of hippocampal CA1 LTP induced by chronic intermittent ethanol exposure is associated with an inhibition of the MAP kinase pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1646–1654. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberts AJ, Heyser CJ, Cole M, Griffin P, Koob GF. Excessive ethanol drinking following a history of dependence: animal model of allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:581–594. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryabinin AE, Criado JR, Henriksen SJ, Bloom FE, Wilson MC. Differential sensitivity of c-Fos expression in hippocampus and other brain regions to moderate and low doses of alcohol. Mol.Psychiatry. 1997;2:32–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryabinin AE, Wang YM. Repeated alcohol administration differentially affects c-Fos and FosB protein immunoreactivity in DBA/2J mice. Alcoholism-Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1646–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanna PP, Simpson C, Lutjens R, Koob G. ERK regulation in chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal. Brain Res. 2002;948:186–191. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schoenbaum G, Setlow B. Lesions of nucleus accumbens disrupt learning about aversive outcomes. J.Neurosci. 2003;23:9833–9841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09833.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schoenbaum G, Shaham Y. The role of orbitofrontal cortex in drug addiction: a review of preclinical studies. Biol.Psychiatry. 2008;63:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schuck S, Soloaga A, Schratt G, Arthur JSC, Nordheim A. The kinase MSK1 is required for induction of c-fos by lysophosphatidic acid in mouse embryonic stem cells. Bmc Molecular Biology. 2003;4 doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silverman AJ, Hoffman DL, Zimmerman EA. The descending afferent connections of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN). Brain Res.Bull. 1981;6:47–61. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(81)80068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sommer WH, Rimondini R, Hansson AC, Heilig M. Up-regulation of voluntary alcohol intake, behavioral sensitivity to stress, and amygdala Crhr1 expression following a history of dependence. Biol Psychiatry . 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.010. Ref Type: In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sumner BE, Cruise LA, Slattery DA, Hill DR, Shahid M, Henry B. Testing the validity of c-fos expression profiling to aid the therapeutic classification of psychoactive drugs. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2004;171:306–321. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsai JC, Liu LX, Cooley BC, Dichiara MR, Topper JN, Aird WC. The Egr-1 promoter contains information for constitutive and inducible expression in transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2000;14:1870–1872. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-1072fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Valdez GR, Koob GF. Allostasis and dysregulation of corticotropin-releasing factor and neuropeptide Y systems: implications for the development of alcoholism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:671–689. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valjent E, Corvol JC, Pages C, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J. Involvement of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade for cocaine-rewarding properties. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8701–8709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Valjent E, Pages C, Rogard M, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J. Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced MAPK/ERK and Elk-1 activation in vivo depends on dopaminergic transmission. Eur.J.Neurosci. 2001;14:342–352. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Dongen YC, Deniau JM, Pennartz CM, Galis-de GY, Voorn P, Thierry AM, Groenewegen HJ. Anatomical evidence for direct connections between the shell and core subregions of the rat nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2005;136:1049–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vertes RP. Interactions among the medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus and midline thalamus in emotional and cognitive processing in the rat. Neuroscience. 2006;142:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51:32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhai H, Li Y, Wang X, Lu L. Drug-induced Alterations in the Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase (ERK) Signalling Pathway: Implications for Reinforcement and Reinstatement. Cell Mol.Neurobiol. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9240-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zoeller RT, Fletcher DL. A single administration of ethanol simultaneously increases c-fos mRNA and reduces c-jun mRNA in the hypothalamus and hippocampus. Brain Research - Molecular Brain Research. 1994;24:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Weiss F. Changes in levels of regional CRF-like-immunoreactivity and plasma corticosterone during protracted drug withdrawal in dependent rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:374–381. doi: 10.1007/s002130100773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic representation of the primary motor cortex (M1) in a rat coronal brain section at Bregma level +2.5 mm. Right. Amphetamine-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 immunoreactivity (ir) in M1 following pretreatment with UO126. Immunohistochemistry for phospho-ERK1/2 clearly demonstrates an increase of phospho-ERK1/2-ir after amphetamine (amph, 10 mg/kg, ip) which is blocked by UO126 (UO, 2.5 nnol, icv) pretreatment. Thus, after icv injection UO seems to penetrate the tissue in sufficient concentration to block the phosphorylation of ERK1/2; saline (sal), vehicle (veh, 4% DMSO, icv); for details, see Materials and Methods.