Abstract

The immature brain in the first several years of childhood is very vulnerable to trauma. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) during this critical period often leads to neuropathological and cognitive impairment. Previous experimental studies in rodent models of infant TBI were mostly concentrated on neuronal degeneration, while axonal injury and its relationship to cell death have attracted much less attention. To address this, we developed a closed controlled head injury model in infant (P7) mice and characterized the temporospatial pattern of axonal degeneration and neuronal cell death in the brain following mild injury. Using amyloid precursor protein (APP) as marker of axonal injury we found that mild head trauma causes robust axonal degeneration in the cingulum/external capsule as early as 30 min post-impact. These levels of axonal injury persisted throughout a 24 hr period, but significantly declined by 48 hrs. During the first 24 hrs injured axons underwent significant and rapid pathomorphological changes. Initial small axonal swellings evolved into larger spheroids and club-like swellings indicating the early disconnection of axons. Ultrastructural analysis revealed compaction of organelles, axolemmal and cytoskeletal defects. Axonal degeneration was followed by profound apoptotic cell death in the posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortex and anterior thalamus which peaked between 16 and 24 hrs post-injury. At early stages post-injury no evidence of excitotoxic neuronal death at the impact site was found. At 48 hrs apoptotic cell death was reduced and paralleled with the reduction in the number of APP-labeled axonal profiles. Our data suggest that early degenerative response to injury in axons of the cingulum and external capsule may cause disconnection between cortical and thalamic neurons, and lead to their delayed apoptotic death.

Keywords: mild traumatic brain injury, neuronal apoptosis, caspase-3, axonal degeneration, amyloid precursor protein, electron microscopy

Introduction

Approximately half a million children sustain traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the USA each year (McArthur et al., 2004), and from all pediatric head trauma hospitalizations, 11.6% are infants below the age of 1 year with fatality rate of 30.5% (Schneier et al., 2006), indicating that the developing infant brain is highly susceptible to trauma. Clinical data suggest that brain injuries in infants (0–2 years) result in poorer outcome than in older children with similar injuries (Anderson et al., 2005) and lead to cognitive and psychological impairment (Kraus et al., 1990; Cattelani et al., 1998).

In the last trimester of fetal life and the first two years after birth the human brain undergoes a period of growth spurt (Dobbing and Sands, 1973). In this period important neurodevelopmental changes occur, including dendritic and axonal growth, synaptogenesis (Dobbing and Sands, 1973, 1979) and oligodendroctyte maturation (Craig et al., 2003). TBI in this critical time leads to profound neuronal and axonal degeneration (Gleckman et al., 1999; Ewing-Cobbs et al., 2000; Geddes et al., 2001). Comparative analysis of brain development between species indicates that in rodents the neurodevelopmental time-frame corresponding to the brain growth spurt, synaptogenesis and strengthening of cortical networks is confined to the first two postnatal weeks (Dobbing and Sands, 1979; Mechawar and Descarries, 2001; Bailey and Johnson, 2004). In addition, the state of white matter development and myelinization in the P7 rodent is similar to that in the human infant (Craig et al., 2003). Based on these and other comparative data, immature rodents 7–14 days of age are considered to correspond to the infant age (up to 12 months) in humans, whereas rodents 17–21 days of age are equivalent to toddlers (2–3 years of age) (Yager and Thornhill, 1997; Rice and Barone, 2000; Kochanek, 2006). Accordingly, these two age groups have been widely used to model the neurodegenerative and neurophatological consequences of TBI in infants and toddlers (Adelson et al., 1996; Prins et al., 1996; Tong et al., 2002; Bittigau et al., 2003; Pullela et al., 2006; Huh et al., 2007). It has been shown that moderate to severe TBI in infant rats (P3–P14) resulted in initial excitotoxic/necrotic cell death at the impact site within 4–5 hours after impact, which was followed by disproportionally larger apoptotic cell death in the cortex and subcortical regions peaking at 24 hrs post-injury (Bittigau et al., 1999; Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2002; Bittigau et al., 2003; Bayly et al., 2006b). However, post-traumatic apoptotic cell death declined significantly during the second postnatal week and was almost a non factor by P14 (Bittigau et al., 1999). Neuronal loss was also found in P11–P17 rodents following controlled cortical impact (Adelson et al., 1996; Tong et al., 2002; Pullela et al., 2006).

Although diffuse axonal damage in human infants is a common consequence of brain injury (Ewing-Cobbs et al., 2000; Geddes et al., 2001), much less attention has been paid to axonal degeneration in rodent models of pediatric TBI compared to injury-induced cell death. Axonal injury has been described in the subcortical white matter following brain trauma in P11–21 rodents (Adelson et al., 2001; Tong et al., 2002; Huh et al., 2007; Raghupathi and Huh, 2007). However, no systematic data are available characterizing axonal degeneration in infant mice following TBI and its relationship to neuronal cell death. To address these questions we established a closed controlled head impact model in P7 mice to mimic accidental head injury which is the predominant cause of TBI in the human infant. We studied the onset, progression and nature of neuronal cell death after mild impact and correlated the results with the temporospatial pattern of axonal degeneration. Here we show that mild head trauma in infant mice results in very early and rapidly progressing axonal degeneration in the cingulum and external capsule, which is followed by substantial apoptotic cell death in functionally and anatomically connected neuronal populations in the injured cortex and thalamus.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The progeny of mThy1-YFP16 mouse line overexpressing yellow fluorescent protein in neurons and axons was used in this study (Feng et al., 2000). Mice were maintained in the animal facility and all surgical procedures were performed according to protocols approved by the Division of Comparative Medicine and NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Injury Device and Procedures

To deliver a precisely controlled impact to the skull of postnatal day 7 (P7) mouse we used an electromagnetic impact device based on a moving coil actuator which was mounted on the arm of a stereotaxic instrument (Benchmark, MyNeurolab, St. Louis, MO). The specifics of the impactor as well as the trauma procedure have been extensively described previously (Bayly et al., 2006b). Animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane in air, midline scalp incision was made and the skin was reflected to expose the skull. A 2 mm-diameter impactor tip was positioned stereotaxically 2 mm anterior to lambda and 1.5 mm lateral to midline facing the left parietal cortex. Speed (3 m/s) was specified by computer control of actuator current and impact depth was calculated at 1 mm. Sham control animals (N=2 at each time point) underwent anesthesia and scalp incision, but did not undergo trauma. Anesthesia was terminated immediately after impact, and pups returned to the dam for recovery.

Histological Methods

Animals were sacrificed at (30 min, 5, 16, 24 and 48 hrs post-injury (4 to 6 animals at each time-point). For some experiments additional time-points were used as specified in Results. Mice were deeply anesthetized with Nembutal and fixed by intracardiac perfusion with cold 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4) containing heparin (3000 U/L) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Brains were removed, post-fixed for 24 hrs in the same fixative. Serial 50 µm vibratome sections were cut and stored in 0.1% PBS/azide.

For immunoelectron microscopy animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and then kept for 2 hrs in glutaraldehyde-free fixative before vibratome sectioning.

For combined light and transmission electron microscopy, mice were perfused with 1.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. The brains were sliced coronally or sagittally into 1mm thick sections, yielding serial slabs containing all portions of the brain. These slabs were osmicated overnight (1% osmium tetroxide), dehydrated in graded ethanols, en-block stained in uranyl acetate, cleared in toluene and embedded flat in araldite. Thin sections (1µm) were serially cut at selected rostro-caudal levels of the brain, using glass knives (1/2 inch wide) and MT-2B Sorval ultratome. These sections were heat dried on glass slides and stained with azure II and methylene blue for evaluation by light microscopy. Areas of special interest were trimmed to a smaller size and ultrathin sections were cut with Reichert-Jung ultramicrotome and picked up onto formvar-coated slot grids (1 × 2mm opening). Slot grids were used because they permit a continuous viewing field uninterrupted by grid mesh bars. Finally sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Ultrastructural observation was performed by JEOL 100C transmission electron microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Coronal, sagittal and horizontal vibratome sections (50 µm) were washed in 0.01M PBS, quenched for 10 min in a solution of methanol containing 3% hydrogen peroxide, and incubated for 1 hr in blocking solution (5% Normal goat serum/0.1 % triton X-100 in PBS) and then with primary antibodies in the same blocking solution overnight at 4°C.. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-cleaved-caspase-3 (D175, polyclonal, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), anti-β-APP (polyclonal, 1:750, ZYMED, San Francisco, CA). Sections were thoroughly rinsed in PBS and incubated for 1 hr in complementary secondary antibodies (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, 1:200 dilution in 1% NGS in 0.01M PBS at pH 7.4). They were then rinsed and reacted in the dark with streptavidin-peroxidase reagent (Standard Vectastain ABC Elite Kit, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Finally, immunoreactive product was visualized by VIP kit (Vector). Stained sections were mounted on glass slides, air-dried, dehydrated and coverslipped. Light and fluorescent photographs were taken using a color CCD (ColorViewII, Soft Imaging System) attached to Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope. Confocal images were taken on laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus Fluoview FV500).

For immunoelectron microscopy 50 µm sagittal and coronal vibratome sections were used. Briefly after the streptavidin-peroxidase step of conventional APP staining, reaction product was visualized with DAB. Sections were ossmicated, dehydrated, and flat embedded in Araldite resin. The selected brain areas were removed, mounted on plastic studs and processed as above.

Morphometric and statistical analysis

Caspase-3 positive cell counts

Three serial caspase-3 stained coronal vibratome sections containing the anterodorsal thalamic nucleus (AD) and separated by 100 µm were used for each time-point (6 animals per group). Caspase-3 positive cells were counted in injured and contralateral sides in blinded fashion. A stereological optical fractionator technique was used to provide an unbiased estimate of the number of cells undergoing apoptotic cell degeneration as described previously (Mac Donald et al., 2007a; Mac Donald et al., 2007b). The area of interest was outlined at low magnification (4x) after which a high magnification (60x) oil objective was used to count individual caspase-3 positive cells. Immunopositive whole cell body profiles with diameters of 8 µm and larger were identified and counted to avoid counting of cell debris, apoptotic bodies, and large cross-sectioned dendrites which are also known to stain with this antibody. A guard zone of 5 µm was used to sample the tissue. Sampling was done in a systematic random fashion throughout the full extent of each outlined region of interest. The inter-section interval, counting frame size, and distance between counting frames were adjusted so that an optimal number of targets were counted for each region of interest. Stereological counting was done with the aid of StereoInvestigator version 5.05.1 (MicroBrightField, Inc, Colchester, VT). The total number of injured neurons per mm3 was calculated by dividing the number of caspase-3 positive cells by the estimated volume of the region of interest determined by the Cavalieri principle and taking into account the shrinkage of the tissue during histological processing (Mac Donald et al., 2007b). Data was reported as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher post-hoc analysis was used.

Axonal profile counts and swelling diameter measurements

The same unbiased methodology was used to count injured axons in the cingulum/external capsule region ipsilateral to the site of trauma. The region of interest was defined as an isosceles triangle with the apex of the cingulum bundle as its vertex (β), the medial edge of the cingulum bundle (α) and the dorsal side of the medial external capsule (γ) as its legs (Fig. 4A). Three serial APP-immunolabeled coronal sections (100 µm apart) adjacent to those used for capspase-3 counting were selected at 30 min, 5, 16 and 24 hrs post-trauma (6 animals per group). Individual injured APP immunolabeled axonal profiles were identified in the outlined regions at 60x oil objective and counted as described previously (Marmarou et al., 2005; Mac Donald et al., 2007b). The total number APP-immunopositive profiles within the cingulum/external capsule region was expressed as the density of axons per mm3. The contralateral side was not included for counting as no APP-labeled profiles were detected in this region. Data was reported as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher post-hoc analysis was used.

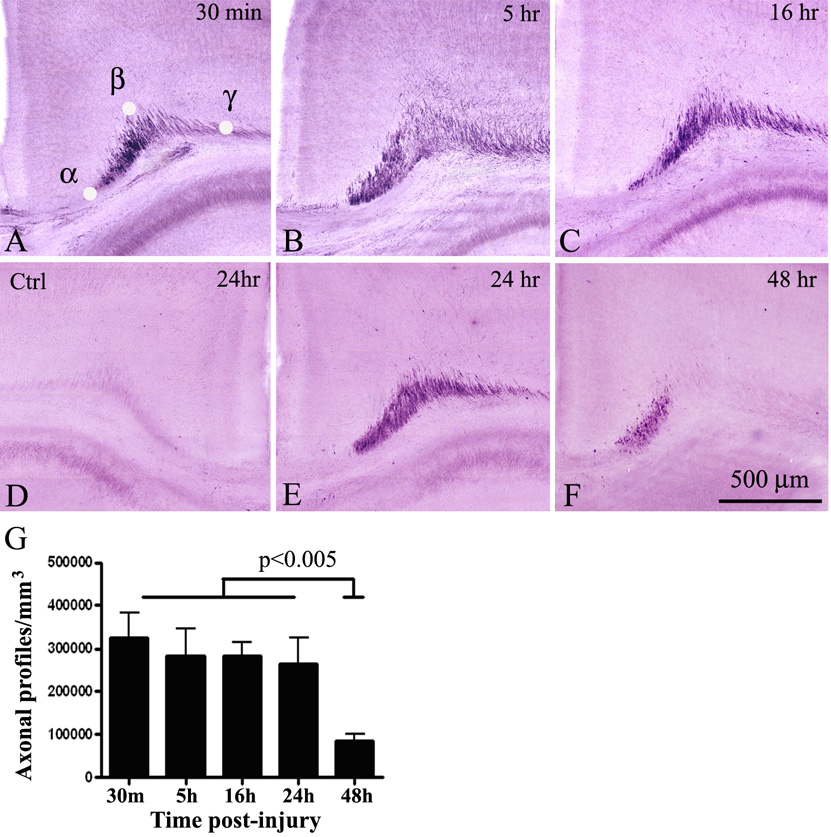

Fig.4.

Time-course of axonal injury in the cingulum/external capsule in P7 mice after mild TBI. Strong APP staining is detected as early as 30 min post-injury (A), and persists at 5 (B), 16 (C) and 24 hrs (E) after trauma. A substantial reduction in APP-immunoreactivity is observed 48 hrs after injury (F). No APP-labeled axons are detected in the contralateral side at all time points (D- representative control section at 24 hrs). F – Quantitative analysis of the density of APP-positive axonal profiles in the cingulum/external capsule at different time-points post-trauma. No significant difference is found between 5, 16 and 24 hrs when compared to 30 min, while substantial reduction in the number of APP-profiles is detected 48 hrs post trauma. α,β,γ in (A) represent reference points determining the triangular area used for axonal profile counts.

To quantify axonal swelling diameter, we used systemic random sampling method within the boundaries of the external capsule of the injured side at the same post-trauma time-intervals as above (six animals per group). Diameter measurement (n = 35) was performed in comparable coronal coordinates at the level of the AD thalamic nucleus from a single APP-immunolabeled section per animal. The external capsule was outlined at low magnification (4x). After that, by focusing through the z axis under 100x oil objective the largest distance across the swelling was measured as described previously (Kelley et al., 2006) using a calibrated tool provided by the software. Data were analyzed and presented as swelling frequency histogram versus diameter at each time-point following TBI. The average swelling diameter was presented as mean ± SD and groups were compared against each other using a one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher post-hoc analysis.

Results

Temporospatial pattern of neuronal cell death following mild TBI in P7 mice

We applied unilateral closed controlled mild impact (1 mm depth) to P7 mice, and assessed the brains at different time-points after injury. In contrast to previously described moderate to severe injuries, mild impact in our model did not result in cavitation or distortion of the cortical mantle at the site of impact as well as in the contralateral hemisphere at 24 hrs (Fig. 1A), 48 hrs and seven days post injury. There was no evidence of hemorrhage on the cortical surface and in the cortical matter at all time points following injury, however red blood cells and macrophage/microglia like cells were frequently detected in the cingulum-extrenal capsule region.

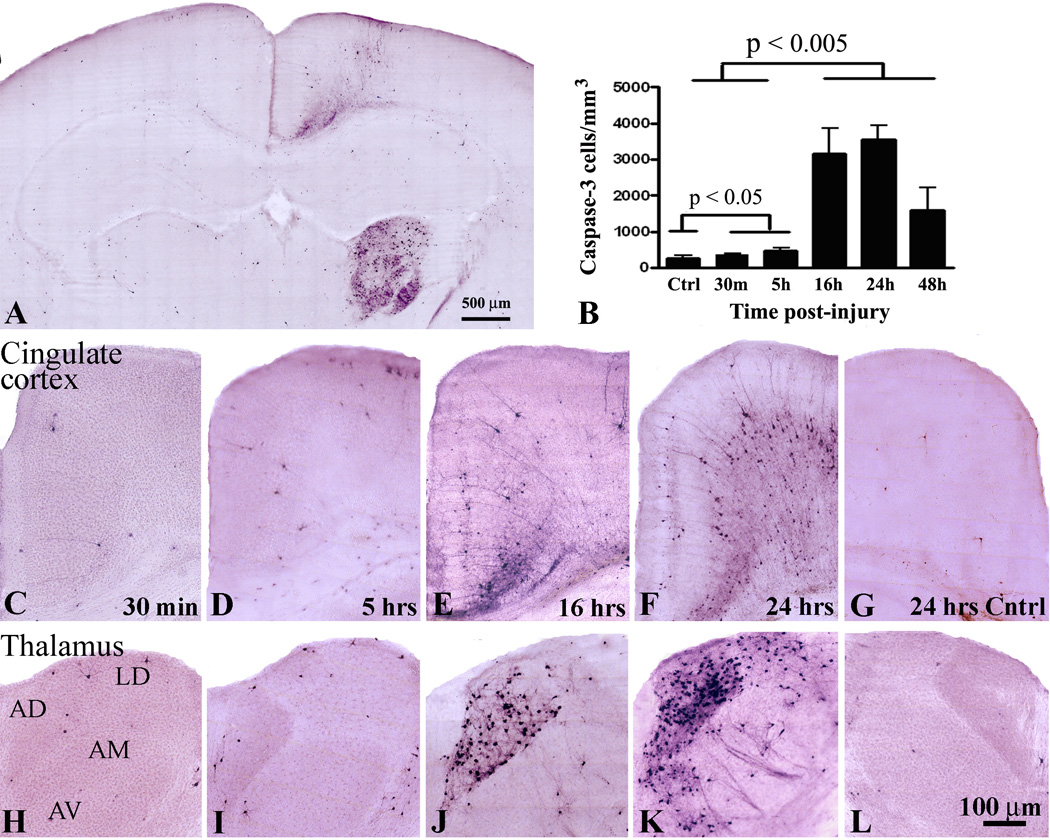

Fig.1.

A – Low power image of a representative coronal section showing the pattern of caspase-3 immunoreactivity in the mouse brain 24 hours following mild TBI. Time course of caspase-3 activation in the posterior cingulate cortex (C–G) and anterior thalamus (H–L) at 30 min (C, H), 5 hrs (D, I), 16 hrs (E,J) and 24 hrs (F, K) after mild injury in P7 mice. No caspase-3 positive cells are detected in the contralateral side (G, L). Note that at 24 hrs post injury additional anterior thalamic nuclei, including the laterodorsa (LD), anteroventral (AM), and to a lesser extent, the anteromedial (AM) show robust caspase-3 immunoreactivity (K). B – Quantitaive analysis of apoptotic cell death progression in the anterodorsal (AD) nucleus of thalamus between 30 min and 48 hrs post-injury.

To assess apoptotic cell death and identify brain regions affected by injury, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) with activated caspase-3 antibody as a specific marker for apoptosis. Initial topographic screening for TBI-induced neuroapoptosis at 24 hrs post-injury revealed that the posterior cingulate cortex and anterior thalamus at the trauma side were the predominant brain regions affected after mild trauma (Fig. 1A). No caspase-3 positive cells were detected in the hippocampus and dentate gyrus. At early time-points after injury (30 min and 5 hrs) we found scattered caspase-3 positive cells in each section of the ipsilateral anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (Fig. 1C, D). In AD thalamus the number of caspase-3 positive cells was only slightly increased compared to that in the contralateral side (Fig. 1H, I, B; p<0.05, n = 6). In contrast, at 16 and 24 hrs post-injury there was a dramatic increase in the number of caspase-3 immunoreactive cells in layers 2/3 and 5/6 of the ipsilateral posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 1E, F) and AD nucleus of thalamus (Fig. 1J, K). Quantitative analysis revealed that at 16 and 24 hrs post-injury the number of apoptotic cells in the ipsilateral AD thalamic nucleus was at least 6-fold higher compared to earlier time-points (Fig. 1B; p<0.005, n = 6). In contrast to 16 hrs, many caspase-3 positive neurons were also detected in the laterodorsal (LD), anteromedial (AM), and anteroventral (AV) nucleus of thalamus at 24 hrs post-injury (Fig. 1, compare J and K). At later time-points post-injury the number of caspase-3 labeled cells in the anterior thalamus and cortex was substantially reduced. At 48 hrs there was approximately a two-fold decrease in number of apoptotic cells in AD nucleus compared to 24 hrs (Fig. 1B). No caspase-3 immunoreactivity was observed at seven days post-injury. These data indicate that following mild TBI apoptotic cell death in thalamus peaks between 16 and 24 hrs post-injury.

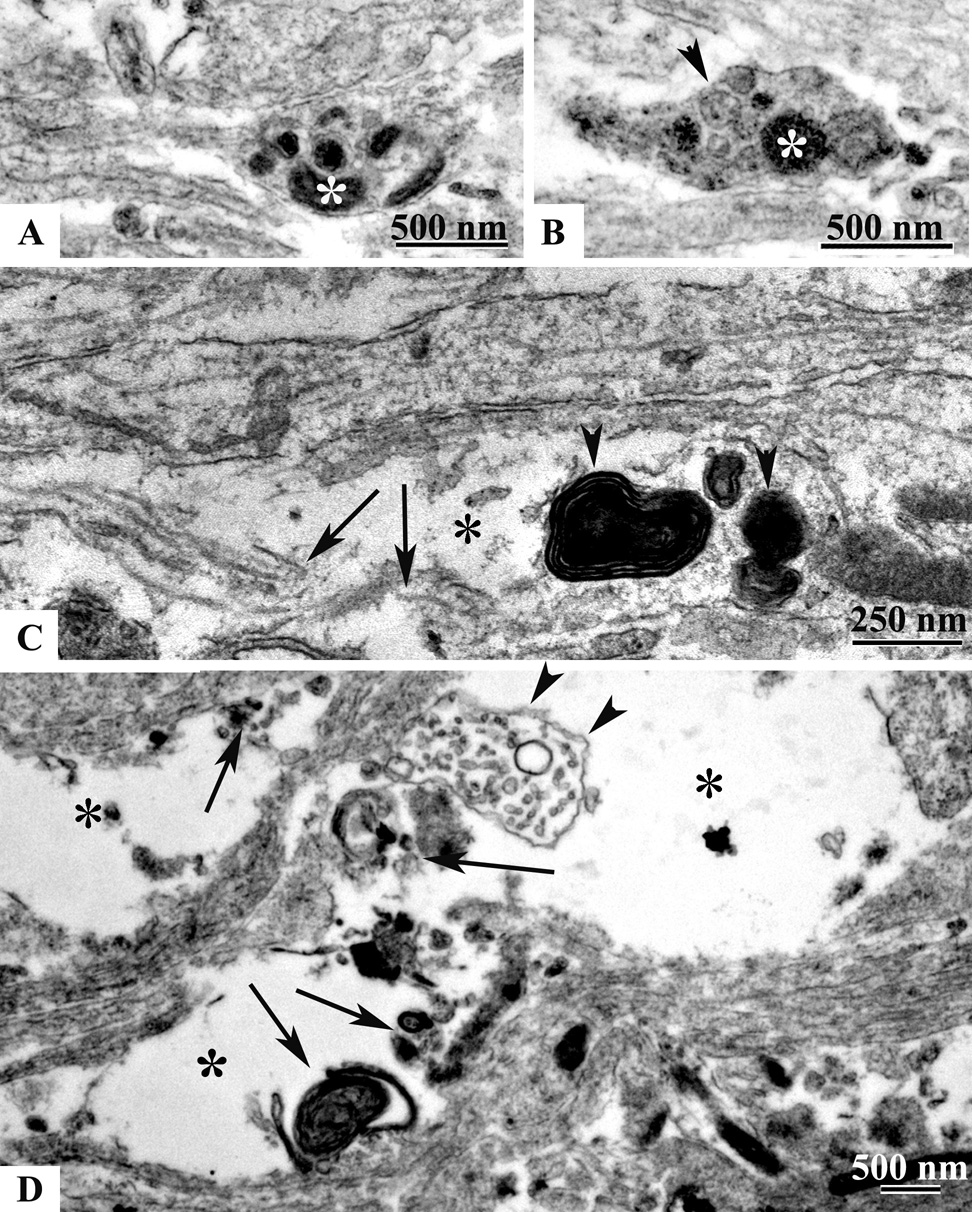

Morphological and ultrastructural changes in degenerating neurons after mild TBI

In addition to neuronal cell perikarya, strong caspase-3 staining was detected in dendritic processes at 16 hrs post injury (Fig. 2A, C). At this time-point only a very small fraction of the degenerating neurons appeared fragmented (Fig. 2C). At 24 hrs post trauma we observed morphological features indicative of more advanced stages of neuronal cell degeneration when compared to 16 hrs. Many of the caspase-3 positive pyramidal neurons in the cortex exhibited fragmented apical dendritic shafts and segmented (apoptotic) cell bodies (Fig. 2, compare A and B). Similar morphological changes were found in the AD thalamic nucleus (Fig. 2, compare C and D).

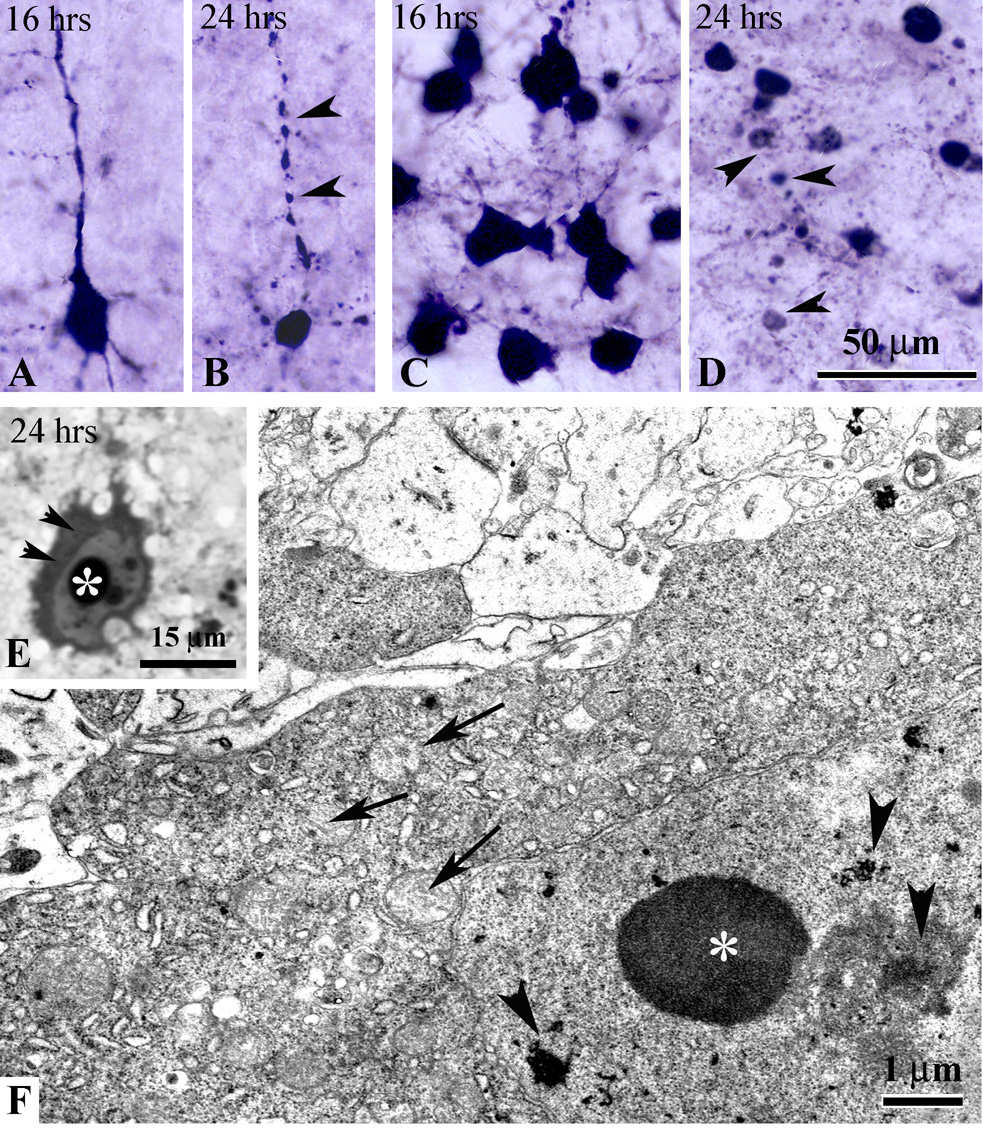

Fig.2.

Morphological changes in degenerating apoptotic neurons in the cortex (A, B) and AD thalamus (C, D). At 16 hrs post-injury caspase-3 positive cortical (A) and thalamic (C) neurons show intense somatic as well as dendritic staining. At 24 hrs, cortical neurons become shrunken (B) with fragmented apical dendritic shafts (arrowheads in B). Many apoptotic bodies (arrowheads in D) and cellular debris are detected in AD thalamus. E – high power light micrograph of apoptotic neuron in the posterior cingulate cortex (plastic section) showing condensation of the cytoplasm (arrowheads) and chromatin balls in the nucleus (asterisk) at 24 hrs. F – electron micrograph of a degenerating neuron in the AD thalamus at 24 hrs post-injury with typical ultrastructural morphological features of apoptosis: condensed cytoplasm, swelling of mitochondria (arrows), intranuclear chromatin balls (asterisk) and fragmentation of the nucleolus (arrowheads).

We also tested whether early excitotoxic cell death which was described previously (Ikonomidou et al., 1996; Bayly et al., 2006b) occurs in infant mice after mild injury. We screened serial rostro-caudal methylene blue/azure stained semithin sections from the ipsilateral cortex at 1, 4, 5 and 6 hrs post-trauma, and found no indication of excitotoxic neuronal injury. To confirm this, we performed ultrastructural analysis of cortical sections in four animals at 4 hrs after injury. Similar to semithin section data, no cells with typical ultrastructural features of excitotoxic death were detected. To further characterize the nature of neuronal cell death we performed electron microscopy analysis of coronal sections from the cortex and thalamus at 24 hrs post-injury when the highest number of caspase-3 positive cells was detected. We found that all degenerating cells in these brain regions exhibited typical signs of neuronal cell apoptosis such as cytoplasmic condensation (Fig. 2E, F), mitochondrial edema, nucleolar disintegration ( Fig. 2F) and nuclear accumulation of round chromatin balls (Fig. 2E, F). Apoptotic cells at different stages of degeneration were detected including phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies and debris by activated microglial cells.

Topographic distribution of injured axons in P7 Thy1-YFP16 mice following mild TBI

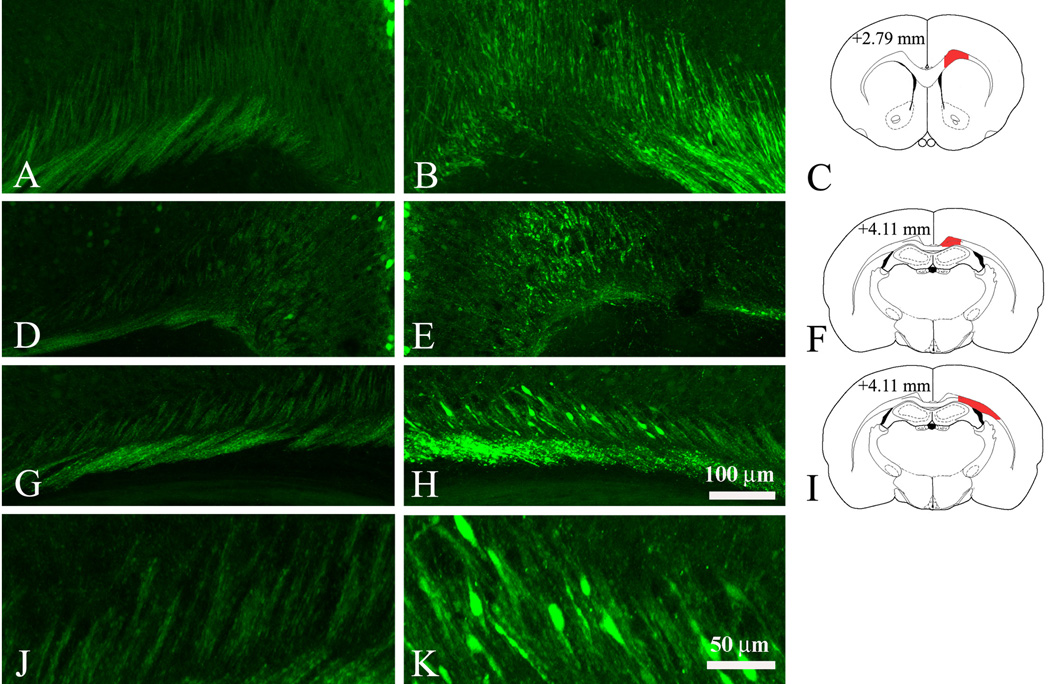

To facilitate the characterization of axonal injury and degeneration following mild TBI in the infant P7 mouse, we used the progeny of mThy1-YFP16 mouse line (Feng et al., 2000; Magill et al., 2007). In this line yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) is expressed at high levels in many neurons throughout the brain. Importantly, numerous axons in white matter tracts such as the corpus callosum, external and internal capsule are labeled with YFP and can be analyzed in detail by fluorescent and confocal microscopy (Fig. 3A, D, G, J). To assess the general topography of post-traumatic axonal injury we analyzed serial rostrocaudal coronal brain sections at 16 hrs after injury. In contrast to the contralateral side (Fig. 3A, D, G, J) we found bundles of swollen and varicose axonal fibers with increased YFP fluorescence in the ipsilateral submantle white matter tracts (Fig. 3B, E, H, K). These changes were observed as anterior as forceps minor (at level +2.79) (Fig. 3B, C), and as posterior as forceps major at level +5.55 (not shown). Many YFP-labeled axonal swellings were detected in the cingulum bundle (Fig. 3B, C, E, F) and external capsule (Fig. 3H, I, K). No YFP-positive axonal swellings were detected in the internal capsule, or in other major ascending or descending brainstem white matter tracts. We also did not find any indication of juxtasomatic bulbs or spheroids formation following injury.

Fig.3.

Identification of subcortical white matter tracts which are affected by mild injury in Thy1-YFP16 mouse at 16 hrs after impact. Axonal injury is determined by the accumulation of very strong YFP-labeling in axonal fibers and swellings in the trauma side (B, E, H, K). Most axons in the contralateral side (A, D, G, J) show smooth YFP-labeling with occasionally appearing swellings. C, F, and I are diagrams of the rostro-caudal level presented in coronal YFP images; areas of interest are filled in red. In the cingulum and external capsule of the trauma side numerous YFP-labeled swollen axons are detected at levels +2.79 (B, C) and + 4.11 (E, F and H, I). J and K are high magnification images taken from G and H showing morphological detail and increased YFP fluorescence in axonal swellings at the trauma side (K) compared to the contralateral side (J). Coordinates show the distance (in mm) from the frontal pole and are adapted from the P6 mouse atlas (Paxinos, Halliday, Watson and Koucherov eds., “Atlas of the developing mouse”, Academic Press, 2007). Scale bar, 100 µm (A, B, D, E, G, H), 50 µm (J, K).

Analysis of axonal degeneration in white matter tracts after mild TBI

Next, we studied the onset and development of axonal degeneration at different time-points following mild injury in regions exhibiting high degree of axonal injury as revealed by YFP staining at 16 hrs post-trauma, i.e. the cingulum/external capsule (Fig. 3). We performed IHC analysis in serial coronal and sagittal sections using an antibody targeting the C terminus of the APP (Stone et al., 2000; Stone et al., 2004). We found very high number of APP-labeled injured axons in this area as early as 30 min following TBI (Fig. 4A, G). Interestingly, between 5 and 24 hrs post TBI the pattern and the number of APP stained axonal profiles was similar to that at 30 min post-trauma (Fig. 4B, C, E) and no statistically significant difference was found between these time-points (Fig. 4G). In contrast, at 48 hrs post trauma we found three-fold reduction in the number of APP-labeled axons and APP immunoreactive profiles were observed predominantly within the cingulum bundle (Fig. 4F, G; p< 0.005). Seven days post trauma only single APP positive swellings were detected in the ipsilateral cingulum.

Progression of morphological changes in injured axons

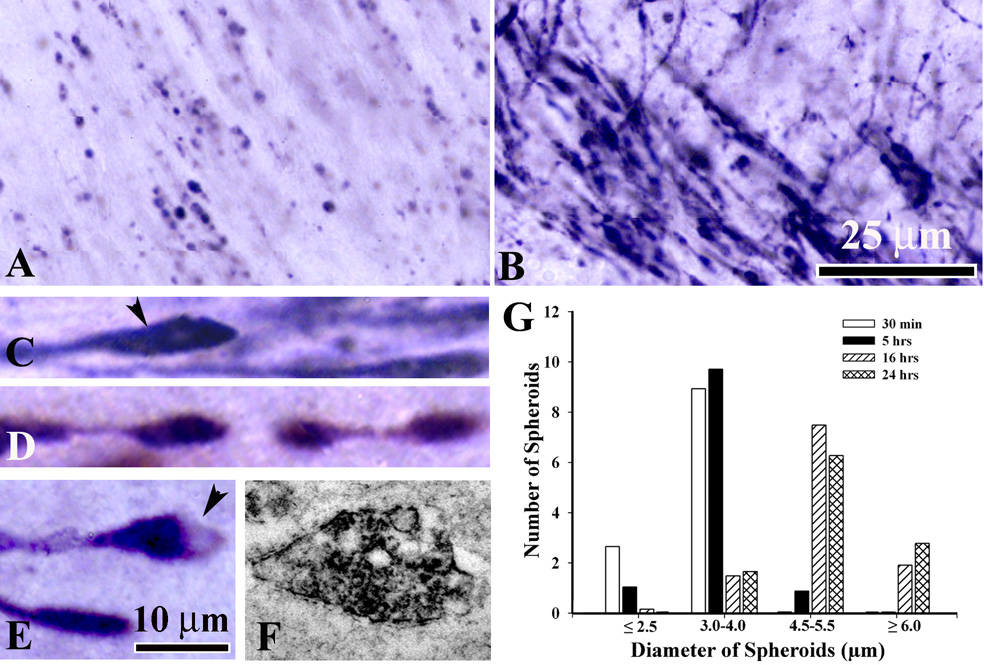

To assess the progression of axonal injury in the infant TBI model, we performed detailed analysis of the morphological changes in degenerating APP-immunostained axonal profiles in the cingulum/external capsule. At 30 min post-injury APP staining appeared as numerous small spheroid profiles and short fiber-like proximal segments ending with a single small size spheroid (Fig. 5A). We found that after 30 min post-injury degenerating axons underwent dramatic morphological changes. By 5 hrs post-injury APP stained profiles appeared in the form of numerous longer and thicker fiber segments some of which ended with larger spheroids and swellings compared to 30 min (Fig. 5B). Between 5 and 24 hrs we observed APP stained axonal swellings of multiple shapes including large clubs (Fig. 5C), bulb-like profiles with proximal and distal segments (not shown) as well as many swellings in a form of beads on a string (Fig. 5D). We also found that many large APP-positive spheroids and bulbs were vacuolated (Fig. 5E). Immunoelectron microscopy showed accumulation of vesicles decorated with APP-immunoprecipitate in many spheroid profiles, suggesting that axonal transport might be impaired in these swollen axonal segments (Fig. 5F). In agreement with the analysis of fluorescently (YFP) labeled axons, we were not able to detect APP immunostained proximal axonal segments or juxtasomatic bulbs in the cortex and thalamus at all time-points post-injury.

Fig.5.

Morphological changes in degenerating APP-immonoreactive axons in the cingulum/external capsule. A – at 30 min post-injury many, predominantly small round APP-stained spheroids are detected. At 5 hrs, numerous injured axons appear as long and thick immunoreactive fibers ending in larger spheroids and swellings (B). At 5 to 24 hrs following mild TBI morphological changes in degenerating axons include the formation of clubs (C, arrowhead), beaded varicose fibers (D), vacuolated spheroids or bulbs (E, arrowhead). Scale bar, 25 µm (A,B), 100 µm (C, D, E). F - electron micrograph showing APP-stained vesiculated spheroid. I – Diameter-frequency histogram demonstrating changes in axonal swelling size at different time-points post-injury: 30 min (white bar), 5hrs (black bar), 16 hrs (striped bar) and 24 hrs (cross-hatched bar).

In addition to the observed changes in the morphology of axonal swellings we also found significant changes in swelling size. In adult models of TBI the progressive increase of axonal spheroids diameter was implicated to axonal disruption and disconnection (Kelley et al., 2006; Farkas and Povlishock, 2007). Therefore, we performed quantitative analysis of the temporal changes in axonal swelling diameter in our infant model of TBI. At 30 min and 5 hrs post TBI the diameter of the majority of spheroids in the cingulum/external capsule fell within the range of 3.0 to 4.0 µm (Fig. 5G) with mean diameter of 2.95 ± 1.66 µm and 3.47 ± 1.94 µm respectively. At 16 and 24 hrs post-injury we found substantial shift in the swelling diameter with the majority of swellings in the range of 4.5 µm and above (Fig. 5G). The average diameter of spheroids at 16 hrs (5.12 ± 1.24 µm) and 24 hrs (5.12 ± 1.24 µm) was significantly higher compared to earlier time-points (p<0.05).

Ultrastructural axonal changes following mild TBI

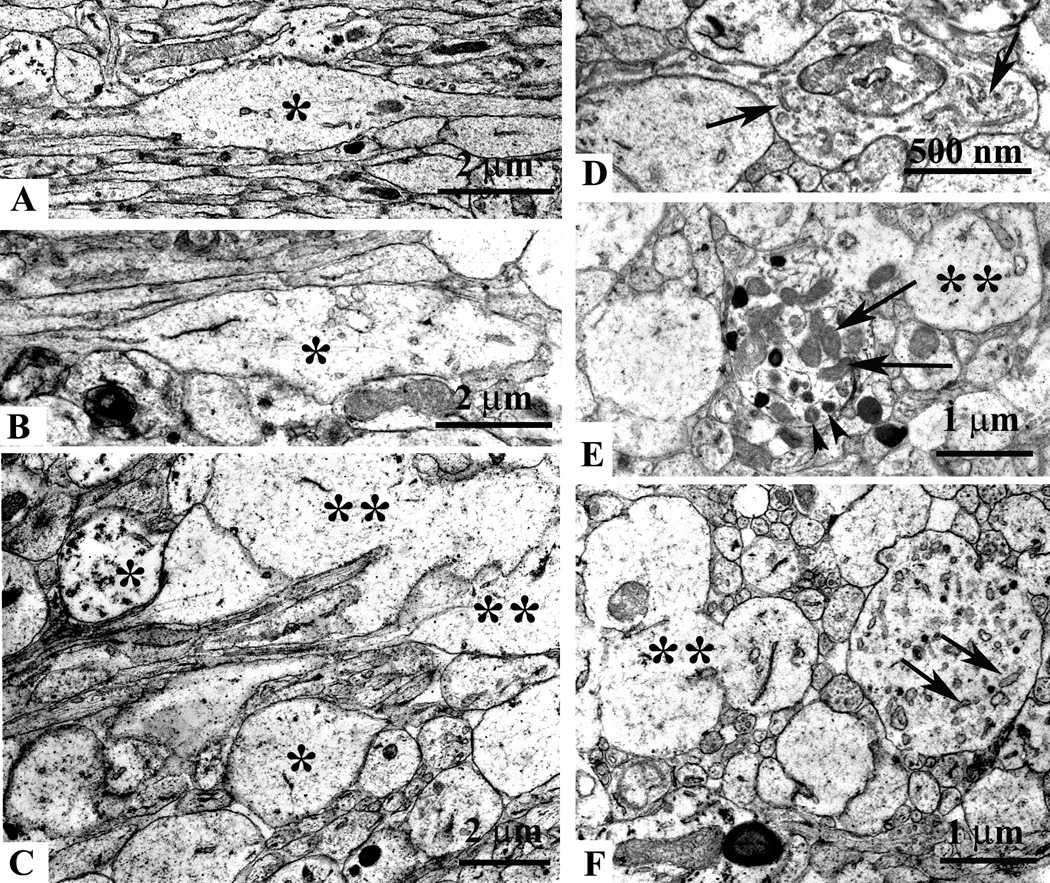

We assessed ultrasctructural changes in injured axons at 4 and 24 hrs post TBI. In the P7 mouse axons in the cingulum/external capsule (Fig. 6, 7) and other subcortical white matter tracts are nonmyelinated and relatively thin. At 4 hrs post-injury many local axonal profiles appeared as single spindle-shaped, elongated club-like or spheroid swellings with intact axolemma (Fig. 6A, B, C, D respectively, asterisk). These segments were devoid of microtubules (Fig. 6A, B, C). We also detected larger swellings with compaction of mitochondria (Fig. 6E, arrows), dense-core (Fig. 6E, arrowheads) and flattened vesicle profiles (Fig. 6D, F, arrowheads). Along with these changes we were able to detect axonal swellings with disrupted cell membranes (Fig. 6C, E, F; double asterisk), which were dispersed among normal looking axonal profiles (Fig. 6F). At 24 hrs post-injury various caliber vesiculated swellings with compaction of mitochondria under an intact axolemma were still observed (Fig. 7A, B). At this time-point the cingulum bundle contained numerous club-like edematous axonal segments with signs of microtubule disconnection, accumulation of myelin figures and axolemmal defects (Fig. 7C). Areas of the cingulum/external capsule appeared vacuous, filled with axoplasmic debris and degenerating vesiculated swellings dispersed among intact axons (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 6.

Ultrastructural axonal changes in the cingulum and external capsule at 5 hrs after mild TBI. Electron micrograph showing local swelling of an injured non-myelinated axon (A, asterisk) and normal appearing axonal segments (A, the lower left side). Note, that the majority of axonal profiles in this micrograph are sectioned longitudinally. Some axonal segments end as clubs or spheroids (single asterisks in B and C), others show disrupted axolemmal membranes (double asterisks in C, E and F). Longitudinal (D) and cross sections (E and F) of swellings showing accumulation of elongated vesicles (arrows in D and F), dense-core vesicles (arrowheads in E) and mitochondria (arrows in E). All swollen segments are devoid of cytoskeletal elements.

Fig. 7.

Ultrastructural axonal changes in the cingulum and external capsule at 24 hrs after mild TBI. Accumulation of mitochondria (asterisk in A and B) and vesicles (arrowhead in B) in axonal spheroids at 24 hrs are similar to that seen at 5 hrs. However, in many axonal club-like swellings (C, asterisk) signs of advanced degeneration such as edema, microtubule discontinuity (C, arrows) and accumulation of myelin figures (C, arrowheads) are present. Large vacuous spaces in the cingulum/external capsule (D, asterisks), remnants of a swollen axonal profiles (D, arrowheads) and scattered axoplasmic debris (D, arrows) are also observed.

Discussion

Accidental traumatic brain injury is the predominant cause of death and disability in young children including infants. To model this scenario in mice we applied a closed controlled impact in P7 mice, a postnatal age which approximately corresponds to the neonatal and infant periods of child development (Yager and Thornhill, 1997; Rice and Barone, 2000; Kochanek, 2006), and studied the neuropathological changes following TBI.

The results of this study revealed that mild TBI to the P7 mouse resulted in profound apoptotic neuronal cell death in the cortex and anterior thalamus and robust axonal injury in major subcortical white matter tracts. In contrast to immature rat models of TBI (Ikonomidou et al., 1996; Bayly et al., 2006b), in the early period (up to 5 hrs) following mild injury to the P7 mouse, we did not observe any morphological features consistent with excitotoxic cell degeneration. The absence of excitotoxic cell death in our mouse model may be explained by the low level of impact severity compared to rat models. We found that mild injury in mice resulted in early apoptotic neuronal death in the thalamus and cortex which gradually progressed, became more widespread and peaked between 16 and 24 hrs. By 48 hrs after injury the number of apoptotic cells in the thalamus and cortex was largely reduced, and no caspase-3 positive neurons were detected by 7 days post-injury. These data demonstrate that, similar to rats (Felderhoff-Mueser et al., 2002; Bittigau et al., 2003), apoptotic cell death is the major contributor to post-traumatic neuronal degeneration in infant mice compared to the delayed, biphasic, and limited apoptosis in adults (Conti et al., 1998; Yakovlev and Faden, 2001; Raghupathi et al., 2002).

Moderate and severe TBI in P11–P21 rodents has been shown to cause axonal degeneration detectable up to two weeks post-injury (Adelson et al., 2001; Raghupathi et al., 2002; Tong et al., 2002; Huh et al., 2007; Raghupathi and Huh, 2007). However, the onset and early progression of axonal injury in white matter tracts in response to brain injury has not been investigated. Analysis of YFP-expressing transgenic mice revealed that the cingulum bundle, corpus callosum and external capsule are the most vulnerable white matter tracts even under conditions of mild trauma. Quantitative analysis of injured axons demonstrated that robust axonal damage occurs as early as 30 min following impact. Surprisingly, the overall number of injured axonal profiles in the cingulum/external capsule remained at the same level for 24 hrs before declining significantly at 48 hrs. This reduction of the number of APP-immunoreactive axons parallels the substantial reduction of apoptotic neuronal cell death in the thalamus and cortex. We also found that between 30 min and 5 hrs post-trauma injured axons undergo rapid and progressive morphological alterations. APP-labeled segments became longer, and in many cases ended in larger spheroids or club-like swellings and were detected up to 24 hrs post-injury. This type of pathomorphological changes and the rapid increase in swelling diameter most likely represent impairment of axonal integrity and eventual axonal disconnection in the developing white matter, and were also implicated in axotomy in adults (Stone et al., 2000; Singleton et al., 2002; Buki and Povlishock, 2006; Kelley et al., 2006). It is further supported by our ultrastructural analysis, which revealed advanced degeneration of many axonal profiles in the form of axolemmal disintegration. In the thalamus of adult rats early perisomatic axonal swellings were also detected at the junction between the proximal unmyelinated and myelinated segments, which was implemented as a point of biomechanical vulnerability (Singleton et al., 2002, Kelley, 2006 #2077). In contrast, after mild injury in infant mice perisomatic axonal injury in the cortex and thalamus was not detected. This difference may reflect the fact that in P7 mice oligodendrocytes are mostly immature and axons are still unmyelinated (Craig et al., 2003).

We do not know yet whether the observed levels of axonal degeneration and death of cortical and thalamic neurons after unilateral mild injury will have significant behavioral and cognitive consequences in infant mice. It has been shown that in P11 mice repetitive mild unilateral trauma does not result in learning deficits at two weeks after injury (Huh et al., 2007). However after severe unilateral injury to P11 rats (Raghupathi and Huh, 2007) brain atrophy and behavioral deficits were detected at four weeks following TBI. In P21 mice subjected to unilateral cortical injury early behavioral changes were manifested as hyperactivity and anxiolysis followed by delayed learning deficits which became evident three months post-trauma (Pullela et al., 2006). Ongoing behavioral studies are aimed to assess the behavioral deficits following graded injury severities including mild impact. It is possible that in the developing brain the behavioral impairment after mild injury could be very subtle due to plasticity and/or the compensatory involvement of the contralateral hemisphere. In this scenario a mid-sagittal impact to the exposed skull, which resulted in extensive bilateral axonal and neuronal degeneration in the same brain areas as in the present study (K.Dikranian, A.Parsadanian, unpublished data), could result in more profound behavioral deficits, and will be also tested in future studies.

One of the important findings in the current study is that robust axonal injury in the cingulum/external capsule develops much earlier than apoptotic neuronal death in the anterior thalamus and posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortex. One explanation of these findings could be that axonal injury and neuronal cell death are distinct and unrelated degenerative processes initiated by mechanical forces. The observed injury of the cingulum/external capsule suggests also that a substantial mechanical strain (tissue deformation) is experienced by these tracts. It has been shown that the infant brain may be under larger peak stress magnitude (deforming force per unit area) compared to the mature brain (Levchakov et al., 2006), and indentation of the skull of infant rats at a similar location used in the current study resulted in very high strain and rapid tissue deformation in the cingulum/external capsule (Bayly et al., 2006a). Another contributing factor to axonal vulnerability may be the fact that subcortical white matter tracts in the P7 mouse are still unmyelinated and contain predominantly immature oligodendrocytes (Craig et al., 2003). These unmyelinated axons pass through a zone of tissue-density transition at the grey-white matter interface, which could make them even more susceptible to injury (Gaetz, 2004). On the other hand, it is well established that anterior thalamic and posterior cingulate cortical neuronal groups that are specifically vulnerable to TBI in our model, are reciprocally connected and their projections pass through the cingulum/external capsule. (Shibata, 1993; Price, 1995). Maintenance of proper synaptic connections and activity dependent trophic support between neurons and their targets is crucial for their survival in the developing brain (Burek and Oppenheim, 1998). Therefore it is possible that injury-induced disconnection between these neurons may contribute to the initiation of the apoptotic cell death process in both neuronal groups. In infant animals similar mechanisms of disconnection-induced apoptotic neuronal cell death has been implicated after visual cortex ablation and after TBI (Conti et al., 1998; Natale et al., 2002; Tong et al., 2002; Repici et al., 2003; Pullela et al., 2006; Igarashi et al., 2007).

Here we demonstrate a complex temporospatial relationship between axonal degeneration and neuronal cell death in infant mice after mild injury. Our data suggest that very early disruption of axonal bundles that pass through the cingulum/external capsule may result in bidirectional loss of functional synaptic connections between anatomically connected cortical and sub-cortical neurons, and may trigger activation of the apoptotic death cascade in these neurons. This infant TBI model will enable future studies to assess behavioral consequences of traumatic injury to the developing brain, will help to elucidate the mechanisms of neurodegeneration after TBI and design therapeutic interventions targeting early axonal degeneration in addition to neuronal cell death.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology and Hope Center for Neurological Disorders grants (WUSM) and in part by NIH grant NS042794 (AP). We would like to thank Dr. J. Olney (Department of Psychiatry, WUSM) for providing access to the electron microscope.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adelson PD, Robichaud P, Hamilton RL, Kochanek PM. A model of diffuse traumatic brain injury in the immature rat. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:877–884. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.5.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelson PD, Jenkins LW, Hamilton RL, Robichaud P, Tran MP, Kochanek PM. Histopathologic response of the immature rat to diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001;18:967–976. doi: 10.1089/08977150152693674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson V, Catroppa C, Morse S, Haritou F, Rosenfeld J. Functional plasticity or vulnerability after early brain injury? Pediatrics. 2005;116:1374–1382. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CD, Johnson GV. Developmental regulation of tissue transglutaminase in the mouse forebrain. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1369–1379. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly PV, Black EE, Pedersen RC, Leister EP, Genin GM. In vivo imaging of rapid deformation and strain in an animal model of traumatic brain injury. J Biomech. 2006a;39:1086–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayly PV, Dikranian KT, Black EE, Young C, Qin YQ, Labruyere J, Olney JW. Spatiotemporal evolution of apoptotic neurodegeneration following traumatic injury to the developing rat brain. Brain Res. 2006b;1107:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Felderhoff-Mueser U, Hansen HH, Ikonomidou C. Neuropathological and biochemical features of traumatic injury in the developing brain. Neurotox Res. 2003;5:475–490. doi: 10.1007/BF03033158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittigau P, Sifringer M, Pohl D, Stadthaus D, Ishimaru M, Shimizu H, Ikeda M, Lang D, Speer A, Olney JW, Ikonomidou C. Apoptotic neurodegeneration following trauma is markedly enhanced in the immature brain. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:724–735. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199906)45:6<724::aid-ana6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buki A, Povlishock JT. All roads lead to disconnection?--Traumatic axonal injury revisited. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006;148:181–193. doi: 10.1007/s00701-005-0674-4. discussion 193-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burek MJ, Oppenheim RW. Cellular interactions that regulate cell death in the developing vertebrate nervous system. In: Koliatsos VE, Ratan RR, editors. Cell death and diseases of the nervous system. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 145–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cattelani R, Lombardi F, Brianti R, Mazzucchi A. Traumatic brain injury in childhood: intellectual, behavioural and social outcome into adulthood. Brain Inj. 1998;12:283–296. doi: 10.1080/026990598122584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti AC, Raghupathi R, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Experimental brain injury induces regionally distinct apoptosis during the acute and delayed post-traumatic period. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5663–5672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig A, Ling Luo N, Beardsley DJ, Wingate-Pearse N, Walker DW, Hohimer AR, Back SA. Quantitative analysis of perinatal rodent oligodendrocyte lineage progression and its correlation with human. Exp Neurol. 2003;181:231–240. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. Quantitative growth and development of human brain. Arch Dis Child. 1973;48:757–767. doi: 10.1136/adc.48.10.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbing J, Sands J. Comparative aspects of the brain growth spurt. Early Hum Dev. 1979;3:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(79)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing-Cobbs L, Prasad M, Kramer L, Louis PT, Baumgartner J, Fletcher JM, Alpert B. Acute neuroradiologic findings in young children with inflicted or noninflicted traumatic brain injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2000;16:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s003810050006. discussion 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas O, Povlishock JT. Cellular and subcellular change evoked by diffuse traumatic brain injury: a complex web of change extending far beyond focal damage. Prog Brain Res. 2007;161:43–59. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)61004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felderhoff-Mueser U, Sifringer M, Pesditschek S, Kuckuck H, Moysich A, Bittigau P, Ikonomidou C. Pathways leading to apoptotic neurodegeneration following trauma to the developing rat brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;11:231–245. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, Keller-Peck C, Nguyen QT, Wallace M, Nerbonne JM, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaetz M. The neurophysiology of brain injury. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:4–18. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddes JF, Vowles GH, Hackshaw AK, Nickols CD, Scott IS, Whitwell HL. Neuropathology of inflicted head injury in children. II. Microscopic brain injury in infants. Brain. 2001;124:1299–1306. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.7.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleckman AM, Bell MD, Evans RJ, Smith TW. Diffuse axonal injury in infants with nonaccidental craniocerebral trauma: enhanced detection by beta-amyloid precursor protein immunohistochemical staining. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:146–151. doi: 10.5858/1999-123-0146-DAIIIW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh JW, Widing AG, Raghupathi R. Basic science; repetitive mild non-contusive brain trauma in immature rats exacerbates traumatic axonal injury and axonal calpain activation: a preliminary report. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:15–27. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi T, Potts MB, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Injury severity determines Purkinje cell loss and microglial activation in the cerebellum after cortical contusion injury. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:258–268. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidou C, Qin Y, Labruyere J, Kirby C, Olney JW. Prevention of trauma-induced neurodegeneration in infant rat brain. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:1020–1027. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley BJ, Farkas O, Lifshitz J, Povlishock JT. Traumatic axonal injury in the perisomatic domain triggers ultrarapid secondary axotomy and Wallerian degeneration. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:350–360. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek PM. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: quo vadis? Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:244–255. doi: 10.1159/000094151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus JF, Rock A, Hemyari P. Brain injuries among infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:684–691. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150300082022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levchakov A, Linder-Ganz E, Raghupathi R, Margulies SS, Gefen A. Computational studies of strain exposures in neonate and mature rat brains during closed head impact. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1570–1580. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Donald CL, Dikranian K, Bayly P, Holtzman D, Brody D. Diffusion tensor imaging reliably detects experimental traumatic axonal injury and indicates approximate time of injury. J Neurosci. 2007a;27:11869–11876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Donald CL, Dikranian K, Song SK, Bayly PV, Holtzman DM, Brody DL. Detection of traumatic axonal injury with diffusion tensor imaging in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2007b doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill CK, Tong A, Kawamura D, Hayashi A, Hunter DA, Parsadanian A, Mackinnon SE, Myckatyn TM. Reinnervation of the tibialis anterior following sciatic nerve crush injury: A confocal microscopic study in transgenic mice. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmarou CR, Walker SA, Davis CL, Povlishock JT. Quantitative analysis of the relationship between intra- axonal neurofilament compaction and impaired axonal transport following diffuse traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1066–1080. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur DL, Chute DJ, Villablanca JP. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: epidemiologic, imaging and neuropathologic perspectives. Brain Pathol. 2004;14:185–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2004.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechawar N, Descarries L. The cholinergic innervation develops early and rapidly in the rat cerebral cortex: a quantitative immunocytochemical study. Neuroscience. 2001;108:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natale JE, Cheng Y, Martin LJ. Thalamic neuron apoptosis emerges rapidly after cortical damage in immature mice. Neuroscience. 2002;112:665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. The rat nervous system. London: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Prins ML, Lee SM, Cheng CL, Becker DP, Hovda DA. Fluid percussion brain injury in the developing and adult rat: a comparative study of mortality, morphology, intracranial pressure and mean arterial blood pressure. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;95:272–282. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullela R, Raber J, Pfankuch T, Ferriero DM, Claus CP, Koh SE, Yamauchi T, Rola R, Fike JR, Noble-Haeusslein LJ. Traumatic injury to the immature brain results in progressive neuronal loss, hyperactivity and delayed cognitive impairments. Dev Neurosci. 2006;28:396–409. doi: 10.1159/000094166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi R, Huh JW. Diffuse brain injury in the immature rat: evidence for an age-at-injury effect on cognitive function and histopathologic damage. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1596–1608. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi R, Conti AC, Graham DI, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Grady MS, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Mild traumatic brain injury induces apoptotic cell death in the cortex that is preceded by decreases in cellular Bcl-2 immunoreactivity. Neuroscience. 2002;110:605–616. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repici M, Atzori C, Migheli A, Vercelli A. Molecular mechanisms of neuronal death in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus following visual cortical lesions. Neuroscience. 2003;117:859–867. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00968-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Barone S., Jr Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108 Suppl 3:511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier AJ, Shields BJ, Hostetler SG, Xiang H, Smith GA. Incidence of pediatric traumatic brain injury and associated hospital resource utilization in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118:483–492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata H. Efferent projections from the anterior thalamic nuclei to the cingulate cortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1993;330:533–542. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RH, Zhu J, Stone JR, Povlishock JT. Traumatically induced axotomy adjacent to the soma does not result in acute neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2002;22:791–802. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00791.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JR, Singleton RH, Povlishock JT. Antibodies to the C-terminus of the beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP): a site specific marker for the detection of traumatic axonal injury. Brain Res. 2000;871:288–302. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JR, Okonkwo DO, Dialo AO, Rubin DG, Mutlu LK, Povlishock JT, Helm GA. Impaired axonal transport and altered axolemmal permeability occur in distinct populations of damaged axons following traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2004;190:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W, Igarashi T, Ferriero DM, Noble LJ. Traumatic brain injury in the immature mouse brain: characterization of regional vulnerability. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:105–116. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager JY, Thornhill JA. The effect of age on susceptibility to hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1997;21:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev AG, Faden AI. Caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways in CNS injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2001;24:131–144. doi: 10.1385/MN:24:1-3:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]