Abstract

Evidence from genetics, co-precipitation and bimolecular fluorescence complementation suggest that three CESAs implicated in making primary wall cellulose in Arabidopsis thaliana form a complex. This study shows the complex has a Mr of approximately 840 kDa in detergent extracts and that it has undergone distinctive changes when extracts are prepared from some cellulose-deficient mutants. The mobility of CESAs 1, 3, and 6 in a Triton-soluble microsomal fraction subject to blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was consistent with a Mr of about 840 kDa. An antibody specific to any one CESA pulled down all three CESAs consistent with their occupying the same 840 kDa complex. In rsw1, a CESA1 missense mutant, extracts of seedlings grown at the permissive temperature have an apparently normal CESA complex that was missing from extracts of seedlings grown at the restrictive temperature where CESAs precipitated independently. In prc1-19, with no CESA6, CESAs 1 and 3 were part of a 420 kDa complex in extracts of light-grown seedlings that was absent from extracts of dark-grown seedlings where the CESAs precipitated independently. Two CESA3 missense mutants retained apparently normal CESA complexes as did four cellulose-deficient mutants defective in proteins other than CESAs. The 840 kDa complex could contain six CESA subunits and, since loss of plasma membrane rosettes accompanies its loss in rsw1, the complex could form one of the six particles which electron microscopy reveals in rosettes.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, cellulose synthase, CESA complex, membrane proteins, primary wall, rsw mutants

Introduction

Cellulose is a major structural polysaccharide that forms microfibrils in the plant cell wall. It is synthesized by rosettes seen by freeze etching the plasma membrane (Brown et al., 1996). A microfibril has some 36 β-1,4 glucan chains and one rosette is thought to elongate all chains simultaneously. Each rosette shows six subunits in the electron microscope so that, if each glucan chain has its own glycosyltransferase, then each of those six visible subunits will themselves contain six enzymes.

The glycosyltransferase family making cellulose was identified by examining expressed sequence tags from cotton fibres that predominantly synthesize cellulose (Pear et al., 1996) and by characterizing cellulose-deficient mutants (Arioli et al., 1998; Taylor et al., 1999, 2000, 2003; Fagard et al., 2000; Burn et al., 2002a; Ellis et al., 2002; Caño-Delgado et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006). CESA glycosyltransferases are large transmembrane proteins (c. 110–120 kDa) with features characteristic of processive glycosyltransferases. CESAs occur in rosettes (Kimura et al., 1999) and a YFP-CESA6 fusion protein moves along linear tracks consistent with microfibril elongation (Paredez et al., 2006).

Cell walls are categorized according to whether they form during cell expansion (primary walls) or after expansion finishes (secondary walls). They differ in structure and polysaccharide composition although their cellulose differs only in physicochemical properties such as chain length and crystallinity (Bertoniere and Zeronian, 1987; Brett, 2000; Lai-Kee-Him et al., 2002). Reflecting those differences, known mutations in six CESA genes of Arabidopsis prominently affect cellulose production in primary walls in the case of CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6 (Arioli et al., 1998; Fagard et al., 2000; Burn et al., 2002a; Ellis et al., 2002; Caño-Delgado et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006) or secondary walls in the case of CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 (Turner and Somerville, 1997; Taylor et al., 1999, 2000, 2003). Recent evidence (Chu et al., 2006; Persson et al., 2007) shows that CESA2 is more important for primary wall deposition than previously thought (Burn et al., 2002a).

Mutational analysis led to the view that CESAs 4, 7, and 8 co-operate to make cellulose since mutations in any one of their genes drastically reduce cellulose deposition in the same secondary cell walls (Taylor et al., 2003). The three CESAs are physically associated in a detergent-solubilized microsomal fraction and the absence of one CESA leaves the other two non-associated in vitro (Taylor et al., 2003) and retained in the endo-membrane system in vivo (Gardiner et al., 2003).

The situation with primary walls shows both similarities and differences. Mutations in CESAs 1, 3, and 6 all affect primary walls (Arioli et al., 1998; Fagard et al., 2000; Burn et al., 2002a; Ellis et al., 2002; Caño-Delgado et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006), but it is more difficult to decide whether mutations in each gene affect precisely the same walls given the difficulties of examining very thin walls whose structure is drastically changed by cell expansion. Mutations in CESA1 (Williamson et al., 2001; Gillmor et al., 2002), including one expected to inactivate the enzyme by changing a critical Asp residue (Beeckman et al., 2002), have very severe phenotypes but are not invariably lethal, implying that some synthesis continues. Known missense mutants of CESA3 (Ellis et al., 2002; Caño-Delgado et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006) have somewhat less severe phenotypes whereas even null mutants of CESA6 have a relatively mild phenotype in roots and essentially none in light-grown hypocotyls (Desnos et al., 1996; Fagard et al., 2000). Moreover, embryos make primary walls without expressing CESA6 (Beeckman et al., 2002). Suggestions based on sequence similarities that CESAs 2, 5, and 9 might partially replace CESA6 (Robert et al., 2004) are strongly supported by recent evidence (Persson et al., 2007; Desprez et al., 2007). Interactions were shown by bimolecular fluorescence complementation which showed Arabidopsis CESAs expressed in tobacco interact with one another in vivo and by co-immunoprecipitation of CESAs 3 and 6. Association may involve disulphide bonds between Cys residues in the zinc-binding region of the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (Kurek et al., 2002; Jacob-Wilk et al., 2006) although the region of the protein from the start of the second transmembrane domain to the C-terminus is implicated in determining which site in the presumptive complex chimeric proteins access (Wang et al., 2006).

This study extends other recent studies of the primary wall CESA complex by showing that CESAs 1, 3, and 6 migrate as an 840 kDa complex on blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and that all three CESAs (3 as well as 1 and 6) co-precipitate in pull-down experiments. Loss of the complex in a cesa1 missense mutant and the existence of a smaller, unstable complex in extracts of a cesa6 null mutant support the complex's importance for cellulose synthesis. Given the loss of rosettes that accompanies loss of the complex in rsw1 and arguments from stoichiometry, it is suggested that the 840 kDa complex may comprise one of the six particles that form the rosettes seen by electron microscopy.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Mutants used were: rsw1 (Ala549Val in CESA1/At4g32410; Arioli et al., 1998); rsw2-1 (Gly429Arg in the KOR endoglucanase/At5g49720; Lane et al., 2001); rsw3 (Ser599Phe in the α-subunit of glucosidase II/At5g63840; Burn et al., 2002b); rsw5 (Pro1056Ser in AtCESA3/At5g05170; Wang et al., 2006); rsw10 (Glu115Lys in ribose 5-phosphate isomerase/At1g71100; Howles et al., 2006); rsw13 (Gly395Glu in glucosidase I/At1g67490; PA Howles and RE Williamson, unpublished results); prc1-19 (Tyr275stop in CESA6 of Ws ecotype; Fagard et al., 2000); eli1-1 (Ser301Phe in AtCESA3/At5g05170; Caño-Delgado et al., 2003). Columbia wild-type was used for controls except when making comparisons with prc1-19 where Ws was used. rsw1, rsw2-1, and rsw3 are available from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio) as CS6554, CS6555, and CS6556, respectively.

Antibody production

The regions encoding the first hypervariable regions (HVR1) of CESAs 1, 3, and 6 were amplified from cDNAs by the PCR using the following primers: CESA1 forward 5′-CGGGATCCGAGAGTTCAATTACGCCCAGGG-3′, CESA1 reverse 5′-TGAGGTACCGACGGGTCCACGATTCTTACA-3′; CESA3 forward 5′-CGGGATCCCAGGTACTGTTGAGTTCAACTA-3′, CESA3 reverse 5′-TGAGGTACCCGACATCTGATGAATAGGGAA-3′; CESA6 forward 5′-ATTGGATCCAGTTTGAGTATGGAAATGG-3′, and CESA6 reverse 5′-TAGGGTACCACCATAGGCCTTGGATGTG-3′. The products were verified by sequencing and cloned into the BamHI and KpnI sites of the pQE32 expression vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) to provide an N-terminal 6His tag.

The three peptides consisted of Glu112 to Pro196 from CESA1, Thr92 to Val173 from CESA3, and Phe113 to Met201 from CESA6, essentially comprizing the HVR1 regions of the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Expression of these peptides in E. coli was induced by 1 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside and pelleted cells were freeze–thawed and sonicated in solubilization buffer (0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M TRIS, 6 M urea, pH 8.0) with protease inhibitors (Complete, EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Each centrifuged extract was passed three times through a 2 ml Ni-NTA column (Qiagen) that was washed sequentially with solubilization buffer adjusted to pH 6.3 and then pH 5.9 (10 column volumes each) before the His-tagged peptide was eluted with three column volumes of pH 4.5 solubilization buffer. Each almost pure peptide was dialysed against phosphate buffered saline and injected into rabbits using standard protocols. To find strongly responding rabbits, sera were tested by immunoblotting for reaction with the His-tagged peptide and with putative CESAs (defined as an approximately 120 kDa band in Arabidopsis extracts that had been resolved by SDS-PAGE). Crude antisera were further purified using either a protein G-Sepharose column (Amersham Biosciences, Bucks, UK) or with a column having the target peptide coupled through cyanogen bromide to Sepharose 6B (Amersham Biosciences). Purified antibodies were diluted to the same volume as the serum from which they had been purified. Affinity purified antibodies detected only 120 kDa bands when crude extracts were immunoblotted. With antibodies purified using protein G, anti-CESA3 and anti-CESA6 still stained only the 120 kDa band in crude extracts but anti-CESA1 also stained a band with a Mr significantly lower than 120 kDa. This protein was not detected in the Triton-soluble supernatants that were used for all subsequent experiments so that, given their simpler preparation, antibodies purified with protein G were routinely used.

Preparation of the Triton-soluble supernatant

Seedlings (1 g fresh weight) were routinely grown with 16 h days at 21 °C for 7–10 d in liquid culture with occasional shaking (Hoagland's liquid medium with glucose 10 g l−1, inositol 96 mg l−1, and thiamine hydrochloride 16.8 mg l−1). Flasks growing dark-grown seedlings were wrapped in aluminium foil and placed inside a box in the same constant environment chamber. Temperature-sensitive rsw mutants were grown at 21 °C with the final two days (or other time as indicated) at either 21 °C or 31 °C, the permissive and restrictive temperatures, respectively. Whole seedlings were drained and ground in a mortar and pestle at 4 °C in extraction buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) with the protease inhibitor cocktail. Extracts were centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min and a crude microsomal pellet prepared by centrifuging the supernatant at 100 000 g for 30 min. The high speed pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of resuspension buffer (extraction buffer containing 2% v/v Triton X-100). Insoluble debris was removed by a further centrifugation (100 000 g for 30 min) and the Triton-soluble supernatant containing detergent-solubilized CESA proteins was used for pull-down experiments and BN-PAGE.

Pull-down experiments

One of the CESA antibodies (50 μl) was added to 950 μl of Triton-soluble supernatant (approximately 3 mg total protein) and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h with end-over-end rotation. After addition of 60 μl of protein G-Sepharose and a further 1 h incubation at 4 °C with end-over-end rotation, samples were centrifuged briefly to pellet the Sepharose. The pellet was washed with three changes of resuspension buffer before boiling in loading buffer (0.125 M TRIS-HCl pH 8.0, 2% SDS, 0.003% bromophenol blue, 15 mg ml−1 of dithiothreitol with 5% sucrose), chilling on ice and analysing by SDS-PAGE, usually using a comb producing a single sample well covering most of the gel. Proteins transferred to Hybond-C nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham) were immunoblotted (1:500 dilution of primary antibody) by standard protocols (Harlow and Lane, 1988) with detection by horseradish peroxidase using 4-chloro 1-naphthol as substrate. In a typical experiment, adjacent strips cut from the membrane were probed with each of the three CESA antibodies.

BN-PAGE

BN-PAGE followed Swamy et al. (2006) using approximately 60 μg of total protein per lane and, after electrophoresis, protein complexes were denatured in the gel with heat and SDS (Kikuchi et al., 2006) to facilitate electrophoretic transfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Coomassie blue was removed by a 1 min wash of the membrane with methanol and immunoblotting was as described for SDS-PAGE. Molecular weight standards are described in the legend to Fig. 2C.

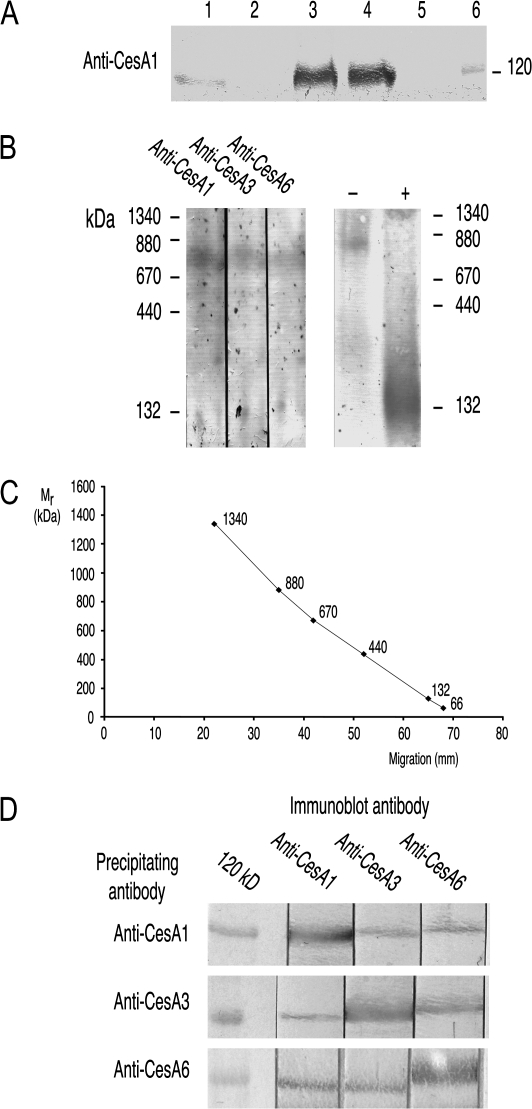

Fig. 2.

Triton-soluble supernatants from light-grown wild-type; preparation and demonstration that CESA proteins occur in 840 kDa complexes. (A) Behaviour of CESAs during preparation of the Triton-soluble supernatant. Aliquots containing 50 μg protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-CESA1. The lanes are: (1) crude extract; (2) 100 000 g supernatant; (3) 100 000 g pellet; (4) Triton-soluble supernatant (100 000 g pellet resuspended in Triton and again centrifuged at 100 000 g); (5) pellet from the second 100 000 g centrifugation; (6) 116 kDa marker. (B) Proteins in the Triton-soluble supernatant resolved by BN-PAGE and immunoblotted with each of the CESA antibodies (left hand panel). Immunostaining of CESA proteins indicates a Mr of about 840 kDa. In the right hand panel, a normal sample (–) is compared with an extract which was boiled in SDS sample buffer before loading (+). A diffuse band in the vicinity of the 132 kDa marker replaces the 840 kDa complex. (C) Calibration curve showing mobility (mm) versus Mr for BN-PAGE. The markers (lowest to highest Mr) are: BSA monomer; BSA dimer; ferritin monomer; thyroglobulin monomer; ferritin dimer; thyroglobulin dimer. (D) Each CESA antibody pulls down all three CESAs from the Triton-soluble supernatant. Tightly bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and adjacent strips immunoblotted with each of the three CESA antibodies. The target of the immunoprecipitating antibody was more abundant than the other two CESA proteins.

Results

Antibody specificity

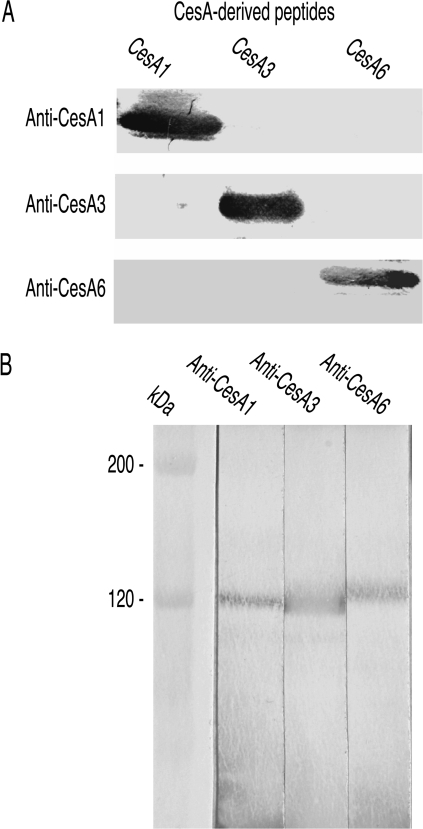

The peptides used as antigens had no significant similarity to each other in BLAST alignments and the antibodies did not recognize non-target peptides when immunoblotted (Fig. 1A). After affinity purification with the peptide antigen, they reacted only with Arabidopsis proteins of appropriate Mr to be CESAs (Fig. 1B) confirming that the same subset of antibodies was responsible for binding to both peptide and Arabidopsis protein. The approximately 120 kDa polypeptide that anti-CESA6 recognized was immediately distinguished from those anti-CESA1 and anti-CESA3 recognized because it migrated just behind them (see, for example, Fig. 1B). Bands were not detected after omitting either primary or secondary antibody.

Fig. 1.

Antibody specificity. (A) The three peptides used as antigens were loaded in adjacent lanes, resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the three antibodies. Each antibody reacts only with its own antigen. (B) Crude extracts of wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings grown in the light were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with affinity purified antibodies. Each antibody recognized only a single band of about 120 kDa (marker is β-galactosidase with predicted Mr of 116 kDa). The band stained by anti-CESA6 migrates just behind the CESA1 and CESA3 bands.

The CESA3 peptide showed no similarities to other Arabidopsis CESAs after BLAST alignments and only small regions of similarity to other Arabidopsis proteins. The CESA1 peptide's similarities to CESA10 are unlikely to present practical problems because CESA10 expression is very low relative to CESA1 (Burn et al., 2002a; see http://mpss.udel.edu/at/). Anti-CESA6 detected no Arabidopsis proteins when CESA6 was removed by mutation in prc1 showing that potential cross-reactions with CESAs 2, 5, and 9 were insignificant (in spite of the 44, 55, and 38 identities, respectively, with the 89 residue CESA6 peptide). It is further concluded that each antibody recognized its own CESA but not the CESA that either of the other antibodies recognized since CESAs 1, 3, and 6 precipitated independently from detergent extracts of rsw1 (Ala549Val in CESA1) and each precipitate reacted only with the antibody that had precipitated it when subsequently analysed by immunoblotting. It is therefore considered that the antibodies were mono-specific in recognizing their target CESAs in both native and denatured states.

Preparing a Triton-soluble supernatant

Demonstrating a complex of CESA proteins required solubilizing the membrane-bound CESAs so that any association reflects protein–protein interaction rather than simply proteins remaining embedded in a common lipid bilayer. The experiments of Turner's group suggest that 2% Triton X-100 achieves this with secondary wall CESAs (Taylor et al., 2000). Immunoblotting showed the fate of CESAs during the steps to produce a Triton-soluble supernatant from a crude microsomal fraction (Fig. 2A shows results using, in this case, anti-CESA1). With constant protein loadings, CESAs were only weakly detected in crude extracts (lane 1). Being membrane proteins, they were absent from the supernatant (lane 2) after centrifugation (100 000 g for 30 min) but prominent in the microsomal pellet (lane 3). After resuspending the microsomal pellet in 2% Triton X-100, most CESAs remained in the supernatant (lane 4 versus lane 5) after centrifuging again at 100 000 g for 30 min. The experiments that follow show that the targets of the three antibodies often co-precipitate from Triton extracts, but their independent precipitation from extracts of rsw1 (Ala549Val) suggests co-precipitation is not due to the proteins still being trapped in the lipid bilayer, a conclusion further supported by the reproducible Mr that CESA complexes show on BN-PAGE. This Triton-soluble supernatant was therefore used for BN-PAGE and for antibody pull-down experiments.

CESAs 1, 3, and 6 migrate at high Mr on BN-PAGE

To see whether primary wall CESAs formed high Mr complexes in the Triton-soluble supernatant, immunoblotting was used to locate CESAs after BN-PAGE. All three CESAs migrated with an estimated Mr of 840 kDa (Fig. 2B, C). Boiling in sample buffer before electrophoresis replaced the 840 kDa bands with strong, rather diffuse staining in the vicinity of the 132 kDa standard that presumably corresponded to CESA monomers (Fig. 2B, right hand lanes).

Pull-down experiments show that complexes contain more than one CESA isoform

Migration on BN-PAGE shows all three CESAs are part of high Mr complexes, but these complexes could be homo- or hetero-oligomers. If hetero-oligomers exist (i.e. complexes containing two or more CESA isoforms), each CESA antibody should pull down all CESAs in the complex, whereas they would only pull-down their target CESA if homo-oligomers exist. All three CESAs were detected in the precipitate irrespective of which antibody performed the pull-down (Fig. 2D). The protein targeted by the pull-down antibody always stained more intensely on the subsequent immunoblot than did the other two CESA proteins. No proteins reacting with CESA antibodies on immunoblots were recovered if we omitted the CESA antibody or the protein G beads from the pull-down step.

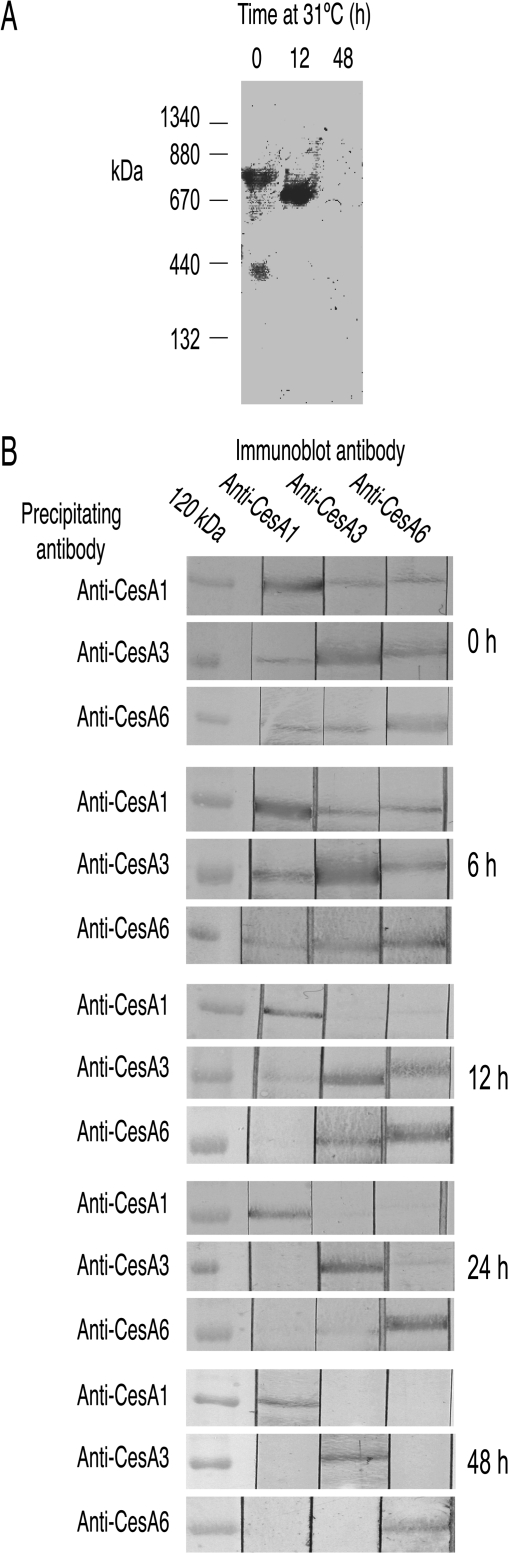

Extracts from rsw1 grown at its restrictive temperature lack the 840 kDa CESA complex

rsw1 (Ala549Val in CESA1) grown at 21 °C showed minimal phenotype (Baskin et al., 1992; Arioli et al., 1998; Sugimoto et al., 2001) and CESAs migrated at 840 kDa on BN-PAGE (Fig. 3A). By contrast, seedlings showed a strong phenotype after 48 h at 30 °C and a high Mr complex was not detected (Fig. 3A). With seedlings grown for 12 h at the restrictive temperature, the complex migrated with a slightly lower Mr than the complex from seedlings not exposed to the restrictive temperature. Pull-down experiments were used to examine the time-course in more detail. Each antibody pulled-down all three CESAs from extracts of seedlings grown at the permissive temperature (Fig. 3B, 0 h panel), but only pulled down its target CESA from extracts of seedlings grown for 48 h at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 3B, 48 h panel). With extracts prepared from seedlings grown for shorter periods at the restrictive temperature, the CESA complex appeared intact after 6 h (all CESAs co-precipitated) but most CESA1rsw1 precipitated only with anti-CESA1 after 12 h (Fig. 3B, 6 h and 12 h panels). CESAs 3 and 6, however, still co-precipitated. After 24 h at the restrictive temperature, the three CESAs precipitated almost independently (Fig. 3B, 24 h panel) as they did at 48 h. (The actual time at the restrictive temperature in these experiments was slightly less than the nominal time since the liquid medium took about 2 h from transfer to approach 31 °C.)

Fig. 3.

The CESA complex in rsw1 is lost at the mutant's restrictive temperature. (A) CESA proteins in extracts from seedlings grown at 20 °C migrate at 840 kDa on BN-PAGE (anti-CESA3 as primary antibody). After 12 h growth at 31 °C, the position of the band indicates a slightly lower Mr and after 48 h growth, no clear band is immunostained. (The staining at about 400 kDa in the 0 h lane was not reproducibly seen.) (B) Pull-down experiments point to progressive loss of the CESA complex at 31 °C. Triton-soluble supernatants were prepared from rsw1 grown at the permissive temperature (0 h) and, as indicated in the appropriate panels, at 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after transferring seedlings to the restrictive temperature. Proteins pulled-down with each antibody were resolved by SDS-PAGE and adjacent strips immunoblotted with each antibody. The CESA complex appears normal after 6 h (each antibody precipitates all three CESAs), but from 12 h onwards, anti-CESA1 precipitates CESA1 with minimal CESA3 and CESA6. At 12 h, there is some precipitation of both CESA3 and CESA6 with either anti-CESA3 or anti-CESA6 but after 24 h and 48 h, all three CESAs precipitate essentially independently.

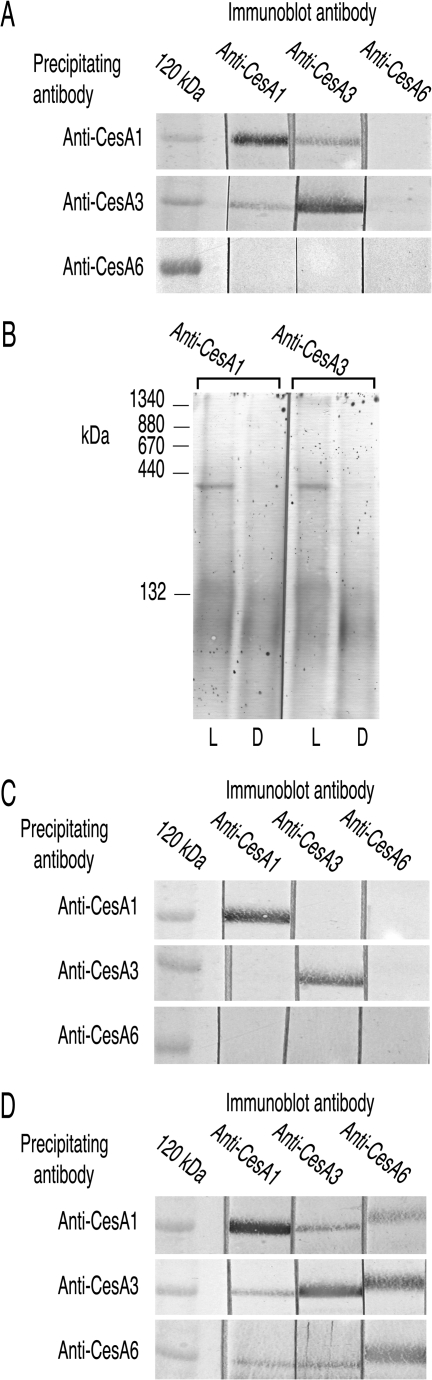

Extracts from light-grown prc1 have a 420 kDa CESA complex that extracts of dark-grown seedlings lack

The premature stop codon in CESA6 in prc1-19 meant that anti-CESA6 did not recognize any proteins in immunoblots of Triton-soluble supernatants, did not pull-down any CESAs (target or non-target), and did not recognize on immunoblots any proteins pulled-down by anti-CESA1 or anti-CESA3 (Fig. 4A). The more severe hypocotyl phenotype in dark-grown prc1 seedlings than in light-grown seedlings (Desnos et al., 1996; Fagard et al., 2000) made it interesting to compare the CESAs in their Triton supernatants. CESA1 and CESA3 migrated at about 420 kDa after BN-PAGE of light-grown prc1 seedling extracts rather than at 840 kDa (Fig. 4B), but only at low Mr when using extracts from dark-grown seedlings (Fig. 4B). Results of pull-down experiments were also consistent with the absence of the CESA complex in extracts of dark-grown prc1-19: anti-CESA1 and anti-CESA3 each pulled-down both CESA1 and CESA3 from extracts of light-grown seedlings (Fig. 4A), but pulled-down only their target CESA from extracts of dark-grown seedlings (Fig. 4C). With extracts from wild-type seedlings, pull-down experiments recovered all three CESAs in extracts of light (Fig. 2D) or dark (Fig. 4D) grown seedlings.

Fig. 4.

CESA1 and CESA3 form a 420 kDa complex in prc1 which is absent in dark-grown seedlings. (A) In pull-down experiments, CESA6 was not detected in the material pulled down by anti-CESA1 or anti-CESA3 and anti-CESA6 did not pull down any proteins that anti-CESA1, anti-CESA3 or anti-CESA6 recognized on immunoblots. CESAs 1 and 3 co-precipitate. Proteins pulled-down with each CESA antibody from Triton-soluble supernatants of light-grown prc1-19 were resolved by SDS-PAGE and adjacent strips immunoblotted with all three antibodies. (B) Proteins in Triton-soluble supernatants of prc1-19 resolved by BN-PAGE show that CESA1 and CESA3 exist in a 420 kDa rather than an 840 kDa complex using extracts from light-grown seedlings (L). This complex is not detected in extracts containing equal amounts of total protein that were prepared from dark-grown seedlings (D). Extracts of this mutant show more immunostaining in the low Mr region than seen with extracts of other mutants. The constant percentage gel used in this experiment provides better resolution in intermediate Mr ranges than the gradient gels routinely used. (C) In pull-down experiments from dark-grown prc1-19 seedlings, CESA1 and CESA3 precipitate only with their respective antibodies consistent with the absence of the 420 kDa complex seen in (B) with BN-PAGE. (D) In pull-down experiments from dark-grown wild-type seedlings, each antibody pulls down all three CESAs showing that, unlike the prc1 complex, the wild-type CESA complex is stable in darkness.

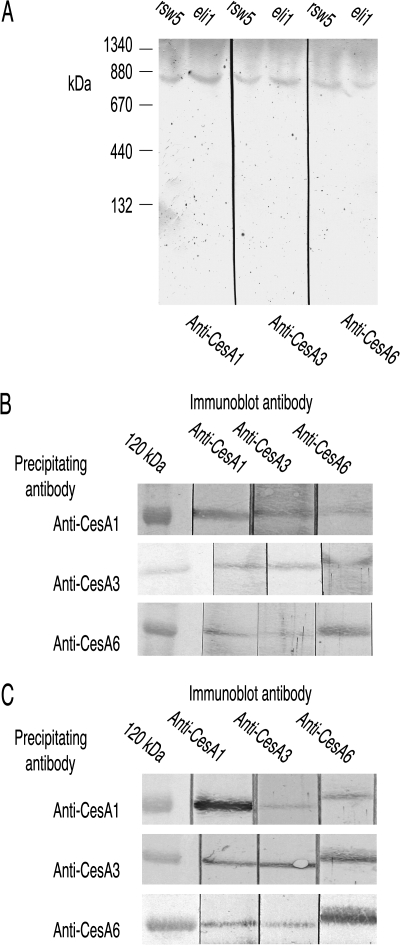

Extracts of two CESA3 missense mutants retain 840 kDa CESA complexes

rsw5 (Wang et al., 2006) and eli1-1 (Caño-Delgado et al., 2003) are both missense mutants of CESA3 (Pro1056Ser for rsw5 and Ser301Phe for eli1-1). rsw5 was grown for the final 48 h at its restrictive temperature whereas the constitutive eli1-1 was grown throughout at 21 °C. CESAs 1, 3, and 6 all migrated with a Mr of 840 kDa on BN-PAGE (Fig. 5A) and each antibody pulled-down all three CESAs from extracts of both mutants (Fig. 5B, C), consistent with both mutants retaining an intact complex.

Fig. 5.

The 840 kDa CESA complex remains intact in the CESA3 missense mutants eli1-1 and rsw5 (latter grown for 48 h at the restrictive temperature). (A) CESAs 1, 3, and 6 are detected at 840 kDa when extracts from both mutants are resolved by BN-PAGE. (B) Each CESA antibody precipitates all three CESAs from a Triton-soluble supernatant prepared from rsw5. (C) Each CESA antibody precipitates all three CESAs from a Triton-soluble supernatant prepared from the constitutive mutant eli1-1 grown at 21 °C.

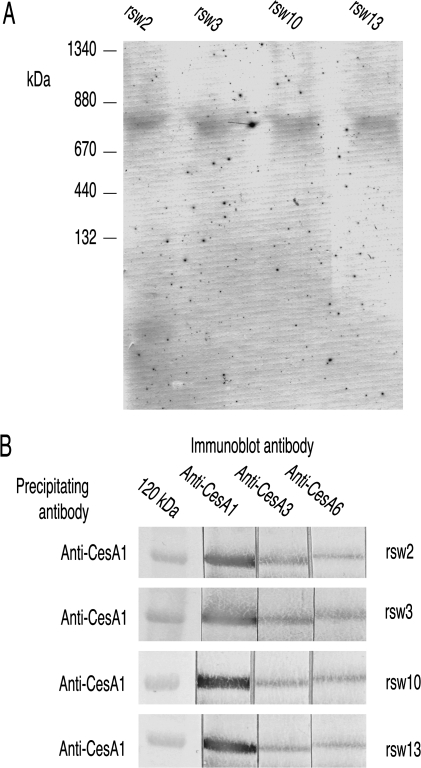

Extracts of other cellulose-deficient mutants retain 840 kDa CESA complexes

Extracts prepared from other radial swelling mutants that are defective in cellulose synthesis because of mutations in genes encoding proteins other than CESAs were also examined (rsw2-1 in the korrigan endocellulase, Lane et al., 2001; rsw13 and rsw3 in the N-glycosylation/ quality control enzymes, glucosidase I and glucosidase II, unpublished results of L Gebbie, P Howles and RE Williamson; Burn et al., 2002b; rsw10, in ribose 5-phosphate isomerase required to synthesize pyrimidine nucleotides to supply UDP-glucose for cellulose synthesis, Howles et al., 2006). BN-PAGE showed CESA3 migrating with a Mr of 840 kDa (Fig. 6A) and anti-CESA1 precipitated all three CESAs from extracts prepared from all mutants (Fig. 6B) showing that all mutants retained CESA complexes containing all three primary wall CESAs.

Fig. 6.

The CesA complex remains intact in rsw2, rsw3, rsw10, and rsw13 grown for 48 h at the restrictive temperature before harvest. (A) BN-PAGE shows an apparently normal CESA complex persists in the Triton-soluble supernatants from these four mutants. Immunostaining with anti-CESA3. (B) Consistent with the persistence of such a CESA complex, anti-CESA1 pulls down all three CESAs from Triton-soluble supernatants.

Discussion

Results from pull-down experiments and BN-PAGE point to similar conclusions regarding how CESAs 1, 3, and 6 behave in detergent extracts of wild type and several cellulose-related mutants. The results with BN-PAGE show that wild type CESAs 1, 3, and 6 occur in complexes with a Mr of about 840 kDa and, with pull-down experiments, that those complexes contain more than one CESA isoform. Extracts of some but not all cellulose-deficient mutants show changes in the CESA complex and analysis of complex behaviour bolsters the idea that the complex contains all three CESAs rather than there being three complexes each containing only two of the three CESAs.

A primary wall CESA complex in wild type

The reliability with which pull-down experiments trap all three CESA isoforms suggests that the 840 kDa complexes seen after BN-PAGE contains more than one CESA isoform. There could be one complex with all three CESAs or three complexes each with only two of these CESA isoforms (1-3, 1-6, and 3-6), a possibility left open by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (Desprez et al., 2007). Findings from rsw1 and prc1 show that two wild-type primary wall CESAs do not form a stable 840 kDa complex in the absence of the third: (i) rsw1 has wild-type CESA3 and CESA6 proteins but, at its restrictive temperature, they do not form an 840 kDa CESA3-CESA6 complex; (ii) prc1 has a complex containing wild-type CESA1 and CESA3 but it has a Mr of 420 kDa in extracts prepared from light-grown seedlings and is absent in extracts prepared from seedlings grown in the dark. This strengthens the hypothesis that the 840 kDa complex contains three CESA isoforms. Current Mr estimates lack the precision to settle the issue of the complex's protein composition. It could certainly be a hexamer as foreshadowed in various models but the presence of other protein(s) which, at the extreme, might mean it contained fewer than six CESA subunits is not excluded.

When pulled-down proteins were immunoblotted, the CESA that was the target of the pull-down antibody was reliably more prominent than the non-target CESAs. A similar effect is visible for CESAs 3 and 6 in the co-immunoprecipitation experiments of Desprez et al. (2007). This is consistent with the Triton-soluble supernatant containing a mixture of free and complexed CESAs; each precipitating antibody would then pull down both the free and complexed forms of its target CESA, but only the complexed form of the non-target CESAs. That hypothesis was not directly supported by BN-PAGE where there was usually little immunostaining of the regions where CESA monomers would be expected to migrate. Again, further approaches (e.g. size exclusion chromatography) will be required to settle how much of the CESAs remain outside the major complex BN-PAGE detects.

Behaviour of the CESA complex in rsw1 extracts

The rsw1 mutant is highly temperature conditional showing near normal growth, cellulose production, and rosettes at the permissive temperature (Arioli et al., 1998; Baskin et al., 1992; Sugimoto et al., 2001). Plants grown for 2 d at the restrictive temperature have less cellulose and few rosettes, changes resulting from CESA1rsw1 having one, slightly larger amino acid residue (Ala549Val) in its catalytic domain (Arioli et al., 1998). Growing rsw1 at either the permissive or the restrictive temperature results in the three primary wall CESAs showing dramatic differences in aggregation in identically prepared extracts. The CESAs precipitate individually in extracts from seedlings grown at the restrictive temperature with no CESA complex detected by BN-PAGE whereas the same CESAs remain part of an 840 kDa complex in extracts from seedlings grown at the permissive temperature and co-precipitate from the same extracts. It is important to stress when comparing the mutant after growth at different temperatures, that differences in the behaviour of identical CESA alleles (in this case CESA1rsw1, CESA3WT and CESA6WT) in detergent extracts prepared identically from homogenization onwards are being observed. Differences in CESA behaviour in the extract seemingly must derive from some difference that was present in vivo as a result of the different growth temperatures. It would be premature to conclude that the non-aggregated state of the CESAs in vitro precisely indicates the in vivo state of the complex at the restrictive temperature although the strong rsw1 phenotype at 30 °C makes plausible a drastic change such as extensive disassembly. Techniques such as bimolecular fluorescence complementation (Desprez et al., 2007) can report on CESA aggregation in vivo.

rsw1 initiates radial swelling within 6–12 h of exposure to the restrictive temperature (Baskin et al., 1992; Sugimoto et al., 2001) and microfibrils on the wall's inner face lose their typical transverse alignment (Sugimoto et al., 2001). Changes in the in vitro aggregation state of the CESAs are detected on a similar time scale. Pull-down experiments using extracts prepared from rsw1 seedlings grown for 12 h at the restrictive temperature suggest that less CESA1rsw1 is present in any complex although CESA3WT and CESA6WT still remain associated with each other as judged by co-precipitation. BN-PAGE shows a CESA complex with a slightly lower Mr perhaps consistent with a complex deficient in one CesA1rsw1 subunit. CESA-containing rosettes probably turn over and move between plasma and endomembrane systems on time scales shorter than those required to induce the rsw1 phenotype (Jacob-Wilk et al., 2006; Paredez et al., 2006) so that changes in the behaviour of CESAs may reflect changes occurring to CESAs that are being delivered de novo to the plasma membrane rather than just reflecting changes occurring to pre-existing complexes already in the plasma membrane.

Behaviour of the CESA complex in prc1 extracts

A Tyr275stop mutation in prc1-19 truncates CESA6 and the aberrant mRNA is probably processed by the nonsense-mediated degradation pathway that removes such messages (Hori et al., 2005). Immunoblots with anti-CESA6 detect no protein with a Mr of 120 kDa, good evidence that anti-CESA6 does not recognize CESAs 2, 5, and 9 which have partial sequence similarity to CESA6. Anti-CESA6 also does not pull-down enough CESA1 or CESA3 for their own antibodies to detect on subsequent immunoblots.

Two types of differences in the aggregation state of CESAs are reported in detergent extracts: those between wild type and mutant and those between mutant grown in the light and mutant grown in darkness. Again, the caveat is repeated that CESA aggregation is being observed in identically prepared detergent extracts so that differences seen here presumably reflect some difference that was present in vivo but does not necessarily report the exact aggregation state of CESAs in vivo. It is further noted that differences between prc1 and wild-type will reflect differences caused by the absence of CESA6 in prc1. By contrast, differences between prc1 grown in the light and darkness will reflect the fact that light conditions in vivo influence the in vitro aggregation behaviour of CESAs 1 and 3 when extracts come from plants lacking CESA6 (prc1) but have no influence when extracts come from wild-type plants containing CESA6.

In extracts of light-grown prc1 seedlings, CESA3 and CESA1 occur in a 420 kDa complex and co-precipitate in pull-down experiments. Although CESA6 is widely expressed, aerial parts of prc1 show no obvious phenotype when grown in the light and only a relatively mild root phenotype (Fagard et al., 2000) suggesting that they make considerable primary wall cellulose without CESA6. Genetic evidence suggests that CESAs 2, 5, and 9 partially replace CESA6 (Persson et al., 2007; Desprez et al., 2007). A 420 kDa complex could accommodate one of those CESAs in addition to CESAs 1 and 3, but current data do not indicate whether it does. Whatever the exact composition of the 420 kDa complex, CESAs 1 and 3 are not part of an 840 kDa complex that is stable in detergent extracts when CESA6 is absent.

Dark-grown prc1 seedlings differ from light-grown seedlings in having a strong hypocotyl phenotype. No 840 kDa or 420 kDa complex is found in detergent extracts from dark-grown plants and, consistent with this, CESA1 and CESA3 precipitate independently. However, although drastic compared with the phenotype in light-grown seedlings, dark-grown seedlings also synthesize some cellulose (Fagard et al., 2000) probably using CESAs 2, 5, and 9 instead of CESA6 (Desprez et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007). If we hypothesize that cellulose synthesis in vivo requires an 840 kDa CESA complex containing three different CESA isoforms, then the most reasonable reconciliation between the in vitro behaviour seen in this study and the in vivo evidence from phenotype and genetics comes from proposing that the primary wall prc1 CESA complex or complexes are more stable in vivo than they are in vitro. This enables the complexes to support some cellulose synthesis in vivo although they disassemble when brought into detergent extracts, either to a 420 kDa complex when derived from light-grown seedlings or seemingly completely when derived from dark-grown seedlings. The nature of the light-related differences in the stability of complexes in vitro remains to be determined.

CESA complexes in other mutants

There were no dramatic changes in either CESA3 mutants examined. Both substitutions inhibited cellulose production without leading to loss of the CESA complex. Presumably both substitutions impair CESA3 function in the complex without causing its loss. Inhibition of synthesis occurs even though neither substitution is in regions of CESA3 conventionally considered important for catalysis, rsw5 being mutated in the short sequence between the eighth transmembrane domain and the protein's C-terminus (Wang et al., 2006) and eli1 being mutated close to the cytoplasmic end of the second transmembrane domain (Caño-Delgado et al., 2003).

None of the other mutants tested (rsw2, rsw3, rsw10, rsw13) showed changed CESA complexes. The KOR endocellulase mutated in rsw2 is probably quite directly involved in glucan processing during cellulose synthesis, but is not part of the CESA complex (Desprez et al., 2007). The two processing enzymes glucosidase I (rsw13) and glucosidase II (rsw3) are probably ER-localized but could affect CESAs through aberrant N-glycosylation. If they do, however, it does not detectably change the CESA complex. Ribose 5-phosphate isomerase (rsw10) is involved in substrate generation at some distance from the steps involving CESAs.

Possible relationship of the 840 kDa complex to rosettes and the production of readily extracted glucan

There is no direct evidence of what happens to rosette terminal complexes at tissue homogenization or when the microsomal fraction is treated with Triton but we suggest that the 840 kDa complex might derive from one of the six subunits that electron microscopy resolves in the rosette. The number of glucan chains (approximately 36) in each microfibril suggests that those six particles may each in turn contain six CESA glycosyltransferases. The 840 kDa complex that is stable through homogenization and Triton extraction plausibly contains six CESA subunits and on this hypothesis could derive from one of the six rosette particles seen by electron microscopy in the plasma membrane. Loss of the CESA complex in mutants would inevitably dismantle rosettes as is known to occur in rsw1 (Arioli et al., 1998). The converse argument, that retention of an 840 kDa complex necessarily means retention of rosettes, does not necessarily follow. If the six particles normally clustered to form the rosette were no longer associated with each other but each remained in the plasma membrane (or even in the endomembrane system), no rosettes would be seen by electron microscopy but the 840 kDa complex might still persist in vivo in the separated particles and so be detectable in Triton extracts.

rsw1 at the restrictive temperature produces a readily extracted glucan which contains short chains of lipid-linked glucan that extract with ammonium oxalate and alkali (Arioli et al., 1998; Peng, 1999; CH Hocart and RE Williamson, unpublished results). Glucan production does not seem related to how stable the 840 kDa complex is in vitro since dark-grown prc1 does not produce glucan (Fagard et al., 2000) even though it lacks a stable 840 kDa complex but rsw2 (Lane et al., 2001; Sato et al., 2001) and rsw3 (Burn et al., 2002b) do accumulate the glucan even though they have stable 840 kDa CESA complexes.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that detergent extracts contain an 840 kDa complex that is potentially big enough to accommodate six CESA monomers drawn from CESA1, CESA3, and CESA6. The complex may plausibly represent one of the six rosette particles seen by electron microscopy if the hypothesis that each rosette needs 36 glycosyltransferases is correct. Some, but not all, cellulose-deficient mutants lack 840 kDa complexes that are stable in detergent extracts. Further analysis of the complex should show the stoichiometry of its CESA components, whether it contains proteins other than CESAs and how well its in vitro behaviour reflects its in vivo behaviour.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Australian Research Council for generous financial support through DP0208889 and DP0557392. We thank Dr Herman Höfte (Versailles) for prc1-19, Professor Michael Bevan (Norwich) for eli1-1, and Paul Howles for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviation

- BN-PAGE

blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

References

- Arioli T, Peng L, Betzner AS, et al. Molecular analysis of cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Science. 1998;279:717–720. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5351.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI, Betzner AS, Hoggart R, Cork A, Williamson RE. Root morphology mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1992;19:427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Beeckman T, Przemeck GK, Stamatiou G, Lau R, Terryn N, De Rycke R, Inzé D, Berleth T. Genetic complexity of cellulose synthase A gene function in Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Plant Physiology. 2002;130:1883–1893. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.010603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoniere NR, Zeronian SH. Chemical characterization of cellulose. ACS Symposium Series. 1987;340:255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Brett CT. Cellulose microfibrils in plants: biosynthesis, deposition, and integration into the cell wall. International Review of Cytology. 2000;199:161–199. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(00)99004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RM, Jr, Saxena IM, Kudlicka K. Cellulose biosynthesis in higher plants. Trends in Plant Science. 1996;1:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Burn JE, Hocart CH, Birch RJ, Cork AC, Williamson RE. Functional analysis of the cellulose synthase genes CesA1, CesA2, and CesA3 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology. 2002a;129:797–807. doi: 10.1104/pp.010931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn JE, Hurley UA, Birch RJ, Arioli T, Cork A, Williamson RE. The cellulose-deficient mutant rsw3 is defective in a gene encoding a putative glucosidase II, an enzyme processing N-glycans during ER quality control. The Plant Journal. 2002b;32:949–960. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caño-Delgado A, Penfield S, Smith C, Catley M, Bevan M. Reduced cellulose synthesis invokes lignification and defense responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal. 2003;34:351–362. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z, Chen H, Zhang Y, et al. Knockout of the AtCESA2 gene affects microtubule orientation and causes abnormal cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2007;143:213–224. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.088393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desnos T, Orbovic V, Bellini C, Kronenberger J, Caboche M, Traas J, Höfte H. Procuste1 mutants identify two distinct genetic pathways controlling hypocotyl cell elongation, respectively in dark- and light-grown Arabidopsis seedlings. Development. 1996;122:683–693. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez T, Juraniec M, Crowell EF, Jouy H, Pochylova Z, Parcy F, Höfte H, Gonneau M, Vernhettes S. Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:15572–15577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706569104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis C, Karafyllidis I, Wasternack C, Turner JG. The Arabidopsis mutant cev1 links cell wall signaling to jasmonate and ethylene responses. The Plant Cell. 2002;14:1557–1566. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard M, Desnos T, Desprez T, Goubet F, Refregier G, Mouille G, McCann M, Rayon C, Vernhettes S, Höfte H. PROCUSTE1 encodes a cellulose synthase required for normal cell elongation specifically in roots and dark-grown hypocotyls of Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:2409–2424. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner JC, Taylor NG, Turner SR. Control of cellulose synthase complex localization in developing xylem. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:1740–1748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.012815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmor CS, Poindexter P, Lorieau J, Palcic MM, Somerville C. β-glucosidase I is required for cellulose biosynthesis and morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;156:1003–1013. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow E, Lane D, editors. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hori K, Watanabe Y. UPF3 suppresses aberrant spliced mRNA in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2005;43:530–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howles PA, Birch RJ, Collings DA, Gebbie LK, Hurley UA, Hocart CH, Arioli T, Williamson RE. A mutation in an Arabidopsis ribose 5-phosphate isomerase reduces cellulose synthesis and is rescued by exogenous uridine. The Plant Journal. 2006;48:606–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob-Wilk D, Kurek I, Hogan P, Delmer DP. The cotton fiber zinc-binding domain of cellulose synthase A1 from Gossypium hirsutum displays rapid turnover in vitro and in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:12191–12196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605098103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Hirohashi T, Nakai M. Characterization of the preprotein translocon at the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts by blue native PAGE. Plant Cell Physiology. 2006;47:363–371. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Laosinchai W, Itoh T, Cui XJ, Linder CR, Brown RM., Jr Immunogold labeling of rosette terminal cellulose-synthesizing complexes in the vascular plant Vigna angularis. The Plant Cell. 1999;11:2075–2085. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.11.2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurek I, Kawagoe Y, Jacob-Wilk D, Doblin M, Delmer D. Dimerization of cotton fiber cellulose synthase catalytic subunits occurs via oxidation of the zinc-binding domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:11109–11114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162077099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai-Kee-Him J, Chanzy H, Muller M, Putaux JL, Imai T, Bulone V. In vitro versus in vivo cellulose microfibrils from plant primary wall synthases: structural differences. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:36931–36939. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DR, Wiedemeier A, Peng L, et al. Temperature sensitive alleles of RSW2 link the KORRIGAN endo-1,4-β-glucanase to cellulose synthesis and cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:278–288. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredez AR, Somerville CR, Ehrhardt DW. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science. 2006;312:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1126551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear JR, Kawagoe Y, Schreckengost WE, Delmer DP, Stalker DM. Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1996;93:12637–12642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L. Characterization of cellulose synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Paredez A, Carroll A, Palsdottir H, Doblin M, Poindexter P, Khitrov N, Auer M, Somerville C. Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2007;104:15566–15571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706592104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert S, Mouille G, Höfte H. The mechanism and regulation of cellulose synthesis in primary walls: lessons from cellulose-deficient Arabidopsis mutants. Cellulose. 2004;11:351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Kato T, Kakegawa K, et al. Role of the putative membrane-bound endo-1,4-β-glucanase KORRIGAN in cell elongation and cellulose synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2001;42:251–263. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Williamson RE, Wasteneys GO. Wall architecture in the cellulose deficient rsw1 mutant of arabidopsis: microfibrils but not microtubules lose their transverse alignment before microfibrils become unrecognisable in the mitotic and elongation zones of roots. Protoplasma. 2001;215:172–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01280312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy M, Siegers GM, Minguet S, Wollscheid B, Schamel WW. Blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) for the identification and analysis of multiprotein complexes. Sci STKE. 2006;345:l4. doi: 10.1126/stke.3452006pl4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NG, Howells RM, Huttly AK, Vickers K, Turner SR. Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2003;100:1450–1455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337628100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NG, Laurie S, Turner SR. Multiple cellulose synthase catalytic subunits are required for cellulose synthesis in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:2529–2540. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.12.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NG, Scheible WR, Cutler S, Somerville CR, Turner SR. The irregular xylem3 locus of Arabidopsis encodes a cellulose synthase required for secondary cell wall synthesis. The Plant Cell. 1999;11:769–780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.5.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SR, Somerville CR. Collapsed xylem phenotype of Arabidopsis identifies mutants deficient in cellulose deposition in the secondary cell wall. The Plant Cell. 1997;9:689–701. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.5.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Howles PA, Cork AH, Birch RJ, Williamson RE. Chimeric proteins suggest that the catalytic and/or C-terminal domains give CesA1 and CesA3 access to their specific sites in the cellulose synthase of primary walls. Plant Physiology. 2006;142:685–695. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.084004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson RE, Burn JE, Hocart CH. Cellulose synthesis: mutational analysis and genomic perspectives using Arabidopsis thaliana. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2001;58:1475–1490. doi: 10.1007/PL00000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]