Abstract

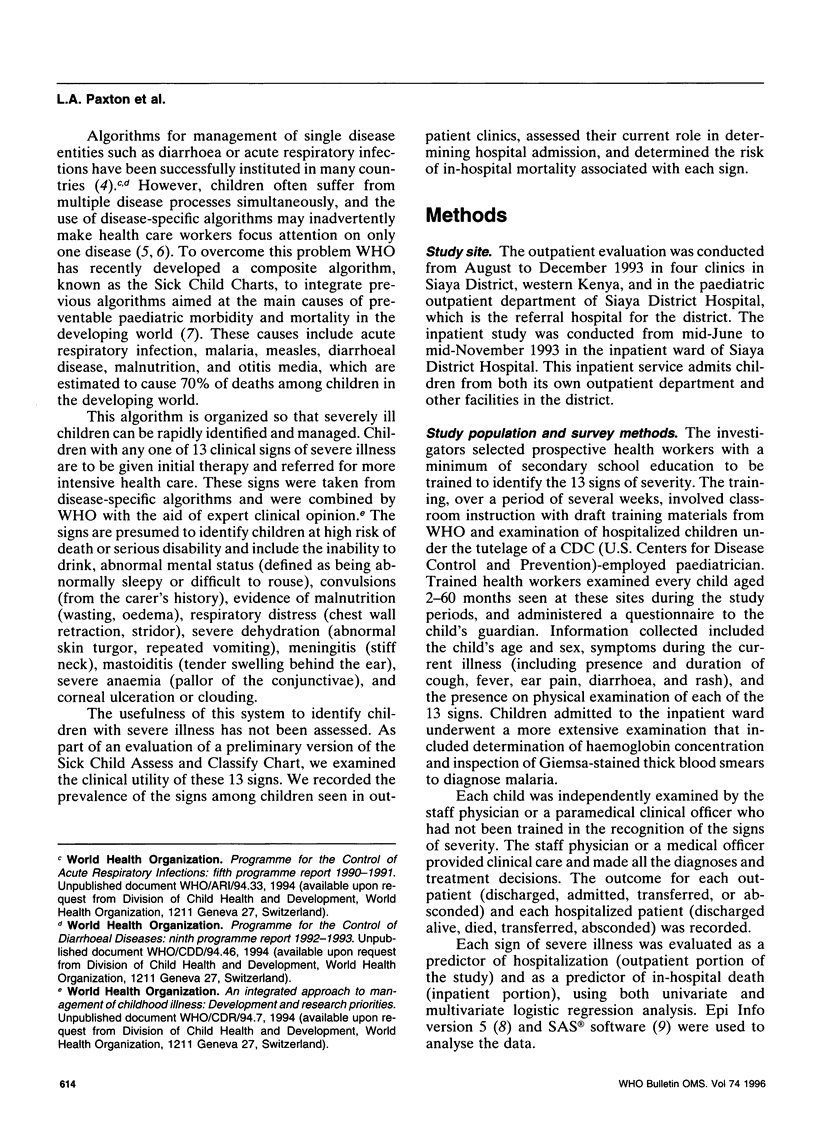

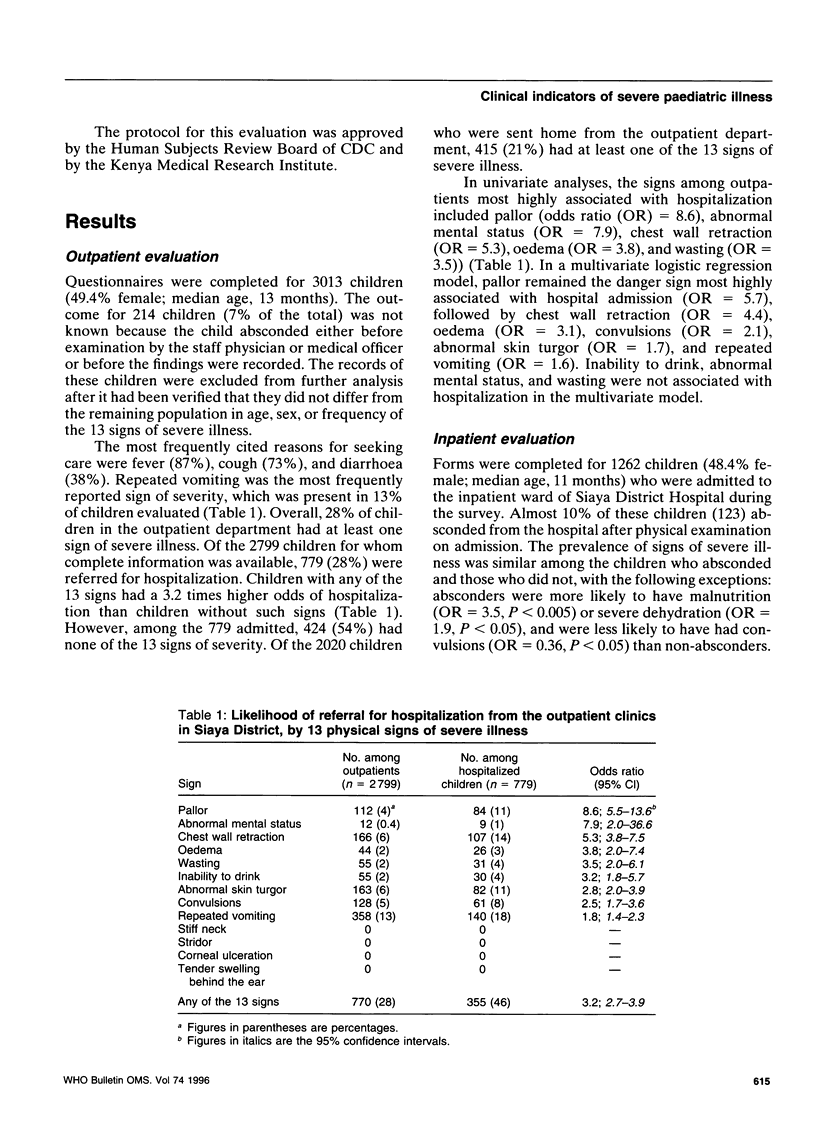

To help reduce paediatric morbidity and mortality in the developing world, WHO has developed a diagnostic and treatment algorithm that targets the principal causes of death in children, which include acute respiratory infection, malaria, measles, diarrhoeal disease, and malnutrition. With this algorithm, known as the Sick Child Charts, severely ill children are rapidly identified, through the presence of any one of 13 signs indicative of severe illness, and referred for more intensive health care. These signs are the inability to drink, abnormal mental status (abnormally sleepy), convulsions, wasting, oedema, chest wall retraction, stridor, abnormal skin turgor, repeated vomiting, stiff neck, tender swelling behind the ear, pallor of the conjunctiva, and corneal ulceration. The usefulness of these signs, both in current clinical practice and within the optimized context of the Sick Child Chart algorithm in a rural district of western Kenya, was evaluated. We found that 27% of children seen in outpatient clinics had one or more of these signs and that pallor and chest wall retraction were the signs most likely to be associated with hospital admission (odds ratio (OR) = 8.6 and 5.3, respectively). Presentation with any of these signs led to a 3.2 times increased likelihood of admission, although 54% of hospitalized children had no such signs and 21% of children sent home from the outpatient clinic had at least one sign. Among inpatients, 58% of all children and 89% of children who died had been admitted with a sign. Abnormal mental status was the sign most highly associated with death (OR = 59.6), followed by poor skin turgor (OR = 5.6), pallor (OR = 4.3), repeated vomiting (OR = 3.6), chest wall retraction (OR = 2.7), and oedema (OR = 2.4). Overall, the mortality risk associated with having at least one sign was 6.5 times higher than that for children without any sign. While these signs are useful in identifying a subset of children at high risk of death, their validation in other settings is needed. The training and supervision of health workers to identify severely ill children should continue to be given high priority because of the benefits, such as reduction of childhood mortality.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Gwatkin D. R. How many die? A set of demographic estimates of the annual number of infant and child deaths in the world. Am J Public Health. 1980 Dec;70(12):1286–1289. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.12.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redd S. C., Bloland P. B., Kazembe P. N., Patrick E., Tembenu R., Campbell C. C. Usefulness of clinical case-definitions in guiding therapy for African children with malaria or pneumonia. Lancet. 1992 Nov 7;340(8828):1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93160-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Rafie M., Hassouna W. A., Hirschhorn N., Loza S., Miller P., Nagaty A., Nasser S., Riyad S. Effect of diarrhoeal disease control on infant and childhood mortality in Egypt. Report from the National Control of Diarrheal Diseases Project. Lancet. 1990 Feb 10;335(8685):334–338. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90616-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]