Abstract

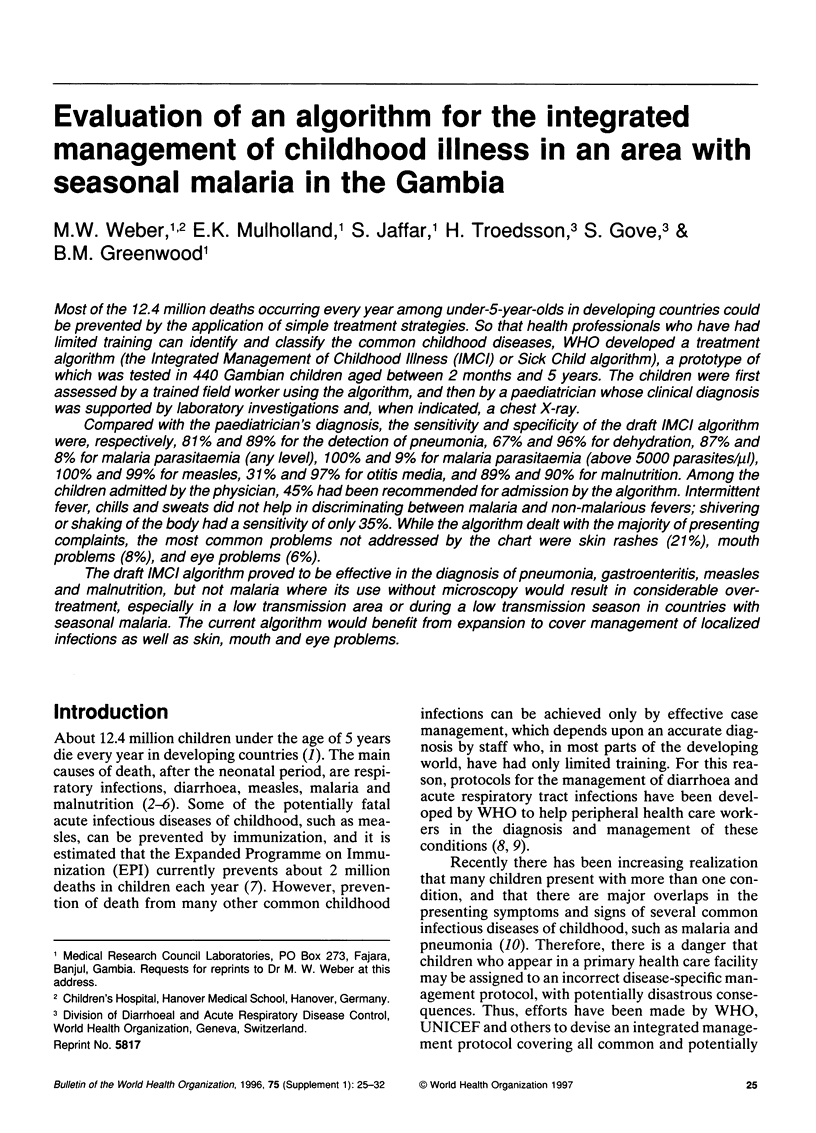

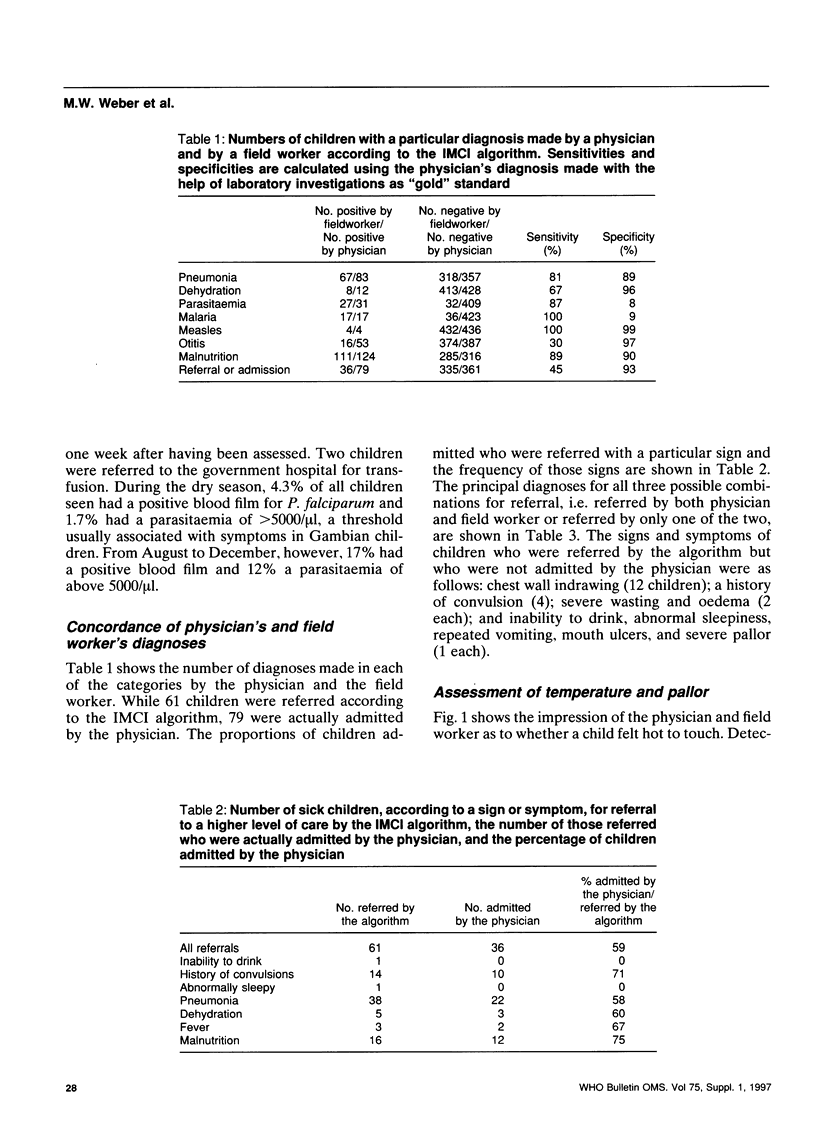

Most of the 12.4 million deaths occurring every year among under-5-year-olds in developing countries could be prevented by the application of simple treatment strategies. So that health professionals who have had limited training can identify and classify the common childhood diseases, WHO developed a treatment algorithm (the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) or Sick Child algorithm), a prototype of which was tested in 440 Gambian children aged between 2 months and 5 years. The children were first assessed by a trained field worker using the algorithm, and then by a paediatrician whose clinical diagnosis was supported by laboratory investigations and, when indicated, a chest X-ray. Compared with the paediatrician's diagnosis, the sensitivity and specificity of the draft IMCI algorithm were, respectively, 81% and 89% for the detection of pneumonia, 67% and 96% for dehydration, 87% and 8% for malaria parasitaemia (any level), 100% and 9% for malaria parasitaemia (above 5000 parasites/microliter), 100% and 99% for measles, 31% and 97% for otitis media, and 89% and 90% for malnutrition. Among the children admitted by the physician, 45% had been recommended for admission by the algorithm. Intermittent fever, chills and sweats did not help in discriminating between malaria and non-malarious fevers; shivering or shaking of the body had a sensitivity of only 35%. While the algorithm dealt with the majority of presenting complaints, the most common problems not addressed by the chart were skin rashes (21%), mouth problems (8%), and eye problems (6%). The draft IMCI algorithm proved to be effective in the diagnosis of pneumonia, gastroenteritis, measles and malnutrition, but not malaria where its use without microscopy would result in considerable over-treatment, especially in a low transmission area or during a low transmission season in countries with seasonal malaria. The current algorithm would benefit from expansion to cover management of localized infections as well as skin, mouth and eye problems.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Beadle C., Long G. W., Weiss W. R., McElroy P. D., Maret S. M., Oloo A. J., Hoffman S. L. Diagnosis of malaria by detection of Plasmodium falciparum HRP-2 antigen with a rapid dipstick antigen-capture assay. Lancet. 1994 Mar 5;343(8897):564–568. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C., Martines J., de Zoysa I., Glass R. I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70(6):705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garenne M., Ronsmans C., Campbell H. The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45(2-3):180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes M., Espino F. E., Abaquin J., Realon C., Salazar N. P. Symptomatic identification of malaria in the home and in the primary health care clinic. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72(3):383–390. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. H. Vaccinations in the health strategies of developing countries. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;76:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland E. K., Simoes E. A., Costales M. O., McGrath E. J., Manalac E. M., Gove S. Standardized diagnosis of pneumonia in developing countries. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992 Feb;11(2):77–81. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dempsey T. J., McArdle T. F., Laurence B. E., Lamont A. C., Todd J. E., Greenwood B. M. Overlap in the clinical features of pneumonia and malaria in African children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993 Nov-Dec;87(6):662–665. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(93)90279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivar M., Develoux M., Chegou Abari A., Loutan L. Presumptive diagnosis of malaria results in a significant risk of mistreatment of children in urban Sahel. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991 Nov-Dec;85(6):729–730. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein W. A., Markowitz L. E., Atkinson W. L., Hinman A. R. Worldwide measles prevention. Isr J Med Sci. 1994 May-Jun;30(5-6):469–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooth I., Björkman A. Fever episodes in a holoendemic malaria area of Tanzania: parasitological and clinical findings and diagnostic aspects related to malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992 Sep-Oct;86(5):479–482. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90076-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rougemont A., Breslow N., Brenner E., Moret A. L., Dumbo O., Dolo A., Soula G., Perrin L. Epidemiological basis for clinical diagnosis of childhood malaria in endemic zone in West Africa. Lancet. 1991 Nov 23;338(8778):1292–1295. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92592-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes E. A., McGrath E. J. Recognition of pneumonia by primary health care workers in Swaziland with a simple clinical algorithm. Lancet. 1992 Dec 19;340(8834-8835):1502–1503. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92757-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Onís M., Monteiro C., Akré J., Glugston G. The worldwide magnitude of protein-energy malnutrition: an overview from the WHO Global Database on Child Growth. Bull World Health Organ. 1993;71(6):703–712. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]